Hematology

I. Anemia

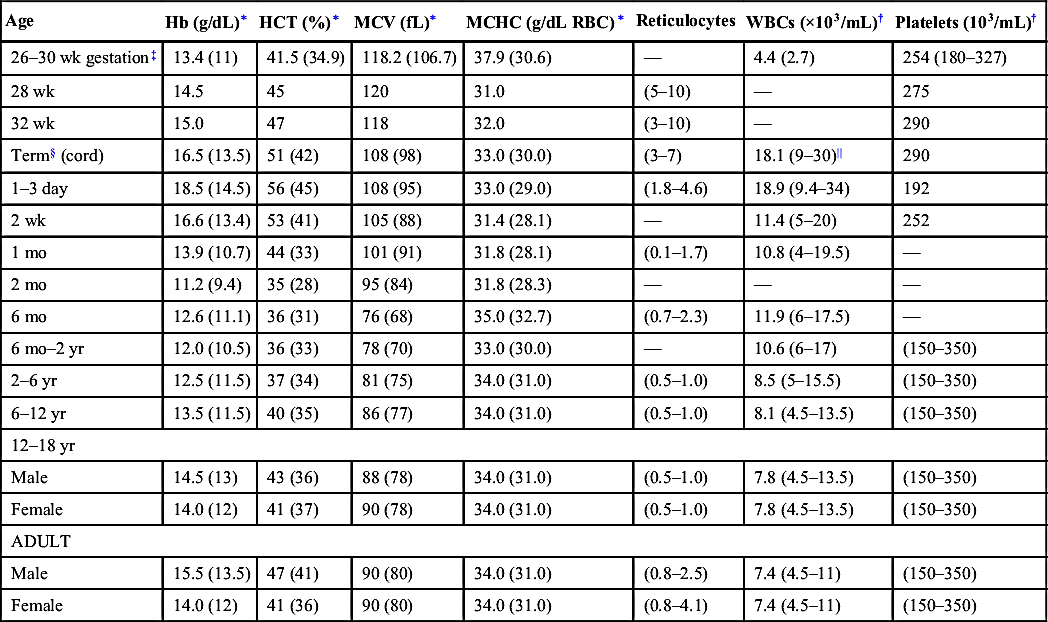

TABLE 14-1

Age-Specific Blood Cell Indices

| Age | Hb (g/dL)∗ | HCT (%)∗ | MCV (fL)∗ | MCHC (g/dL RBC)∗ | Reticulocytes | WBCs (×103/mL)† | Platelets (103/mL)† |

| 26–30 wk gestation‡ | 13.4 (11) | 41.5 (34.9) | 118.2 (106.7) | 37.9 (30.6) | — | 4.4 (2.7) | 254 (180–327) |

| 28 wk | 14.5 | 45 | 120 | 31.0 | (5–10) | — | 275 |

| 32 wk | 15.0 | 47 | 118 | 32.0 | (3–10) | — | 290 |

| Term§ (cord) | 16.5 (13.5) | 51 (42) | 108 (98) | 33.0 (30.0) | (3–7) | 18.1 (9–30)|| | 290 |

| 1–3 day | 18.5 (14.5) | 56 (45) | 108 (95) | 33.0 (29.0) | (1.8–4.6) | 18.9 (9.4–34) | 192 |

| 2 wk | 16.6 (13.4) | 53 (41) | 105 (88) | 31.4 (28.1) | — | 11.4 (5–20) | 252 |

| 1 mo | 13.9 (10.7) | 44 (33) | 101 (91) | 31.8 (28.1) | (0.1–1.7) | 10.8 (4–19.5) | — |

| 2 mo | 11.2 (9.4) | 35 (28) | 95 (84) | 31.8 (28.3) | — | — | — |

| 6 mo | 12.6 (11.1) | 36 (31) | 76 (68) | 35.0 (32.7) | (0.7–2.3) | 11.9 (6–17.5) | — |

| 6 mo–2 yr | 12.0 (10.5) | 36 (33) | 78 (70) | 33.0 (30.0) | — | 10.6 (6–17) | (150–350) |

| 2–6 yr | 12.5 (11.5) | 37 (34) | 81 (75) | 34.0 (31.0) | (0.5–1.0) | 8.5 (5–15.5) | (150–350) |

| 6–12 yr | 13.5 (11.5) | 40 (35) | 86 (77) | 34.0 (31.0) | (0.5–1.0) | 8.1 (4.5–13.5) | (150–350) |

| 12–18 yr | |||||||

| Male | 14.5 (13) | 43 (36) | 88 (78) | 34.0 (31.0) | (0.5–1.0) | 7.8 (4.5–13.5) | (150–350) |

| Female | 14.0 (12) | 41 (37) | 90 (78) | 34.0 (31.0) | (0.5–1.0) | 7.8 (4.5–13.5) | (150–350) |

| ADULT | |||||||

| Male | 15.5 (13.5) | 47 (41) | 90 (80) | 34.0 (31.0) | (0.8–2.5) | 7.4 (4.5–11) | (150–350) |

| Female | 14.0 (12) | 41 (36) | 90 (80) | 34.0 (31.0) | (0.8–4.1) | 7.4 (4.5–11) | (150–350) |

Hb, Hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; MCHC, mean cell hemoglobin concentration; MCV, mean corpuscular volume; RBC, red blood cell; WBC, white blood cell.

∗ Data are mean (− 2 SD).

† Data are mean (± 2 SD).

‡ Values are from fetal samplings.

§ 1 mo, capillary hemoglobin exceeds venous: 1 hr: 3.6 -g difference; 5 day: 2.2 -g difference; 3 wk: 1.1- g difference.

|| Mean (95% confidence limits).

Data from Forestier F, Dattos F, Galacteros F, et al. Hematologic values of 163 normal fetuses between 18 and 30 weeks of gestation. Pediatr Res. 1986;20:342; Oski FA, Naiman JL. Hematological Problems in the Newborn Infant. Philadelphia: WB Saunders;1982; Nathan D, Oski FA. Hematology of Infancy and Childhood. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998; Matoth Y, Zaizor K, Varsano I, et al. Postnatal changes in some red cell parameters. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1971;60:317; and Wintrobe MM. Clinical Hematology. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1999.

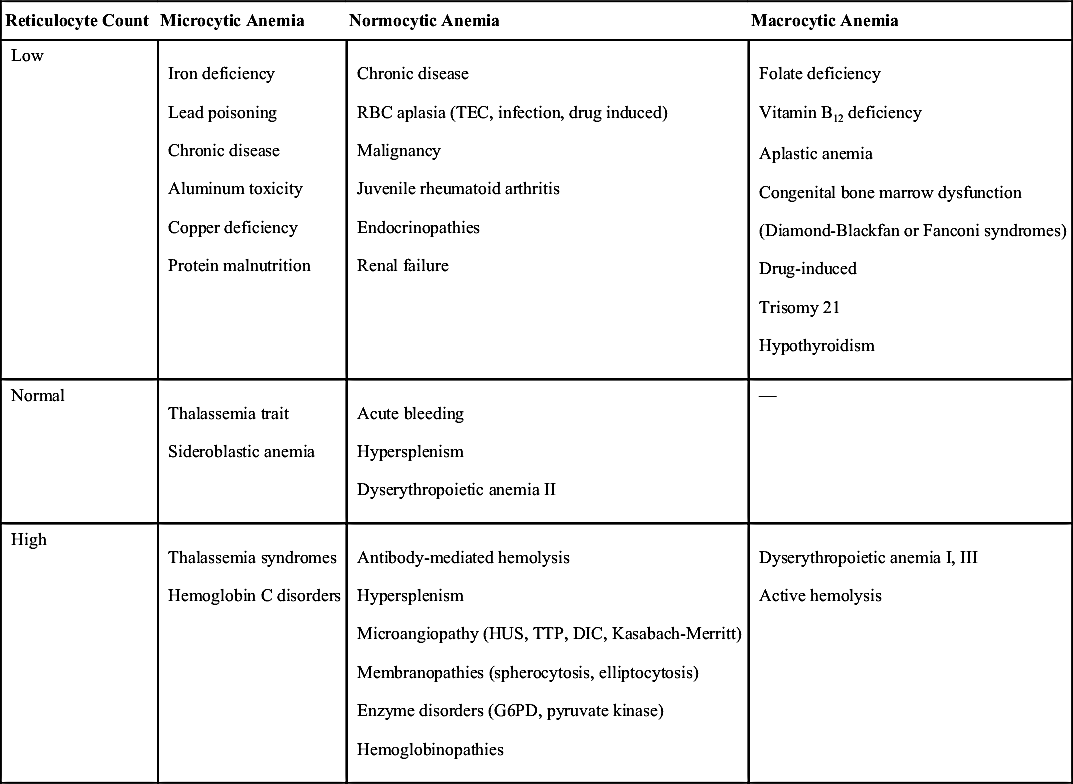

TABLE 14-2

DIC, Disseminated intravascular coagulation; G6PD, glucose-6–phosphate dehydrogenase; HUS, hemolytic-uremic syndrome; RBC, red blood cell; TEC, transient erythroblastopenia of childhood; TTP, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura.

II. Hemoglobinopathies

TABLE 14-3

Neonatal Hemoglobin (Hb) Electrophoresis Patterns∗

| FA | Fetal Hb and adult normal Hb; the normal newborn pattern |

| FAV | Indicates presence of both HbF and HbA, but an anomalous band (V) is present that does not appear to be any of the common Hb variants. |

| FAS | Indicates fetal Hb, adult normal HbA, and HbS, consistent with benign sickle cell trait |

| FS | Fetal and sickle HbS without detectable adult normal HbA. Consistent with clinically significant homozygous sickle Hb genotype (S/S) or sickle β-thalassemia, with manifestations of sickle cell anemia during childhood. |

| FC† | Designates presence of HbC without adult normal HbA. Consistent with clinically significant homozygous HbC genotype (C/C), resulting in a mild hematologic disorder presenting during childhood. |

| FSC | HbS and HbC present. This heterozygous condition could lead to manifestations of sickle cell disease during childhood. |

| FAC | HbC and adult normal HbA present, consistent with benign HbC trait |

| FSA | Heterozygous HbS/β-thalassemia, a clinically significant sickling disorder |

| F† | Fetal HbF is present without adult normal HbA. May indicate delayed appearance of HbA but is also consistent with homozygous β-thalassemia major or homozygous hereditary persistence of fetal HbF. |

| FV† | Fetal HbF and an anomalous Hb variant (V) are present. |

| AF | May indicate prior blood transfusion. Submit another filter paper blood specimen when infant is 4 mo of age, at which time the transfused blood cells should have been cleared. |

NOTE: HbA: α2β2; HbF: α2γ2; HbA2: α2δ2.

∗ Hemoglobin variants are reported in order of decreasing abundance; for example, FA indicates more fetal than adult hemoglobin.

† Repeat blood specimen should be submitted to confirm original interpretation.

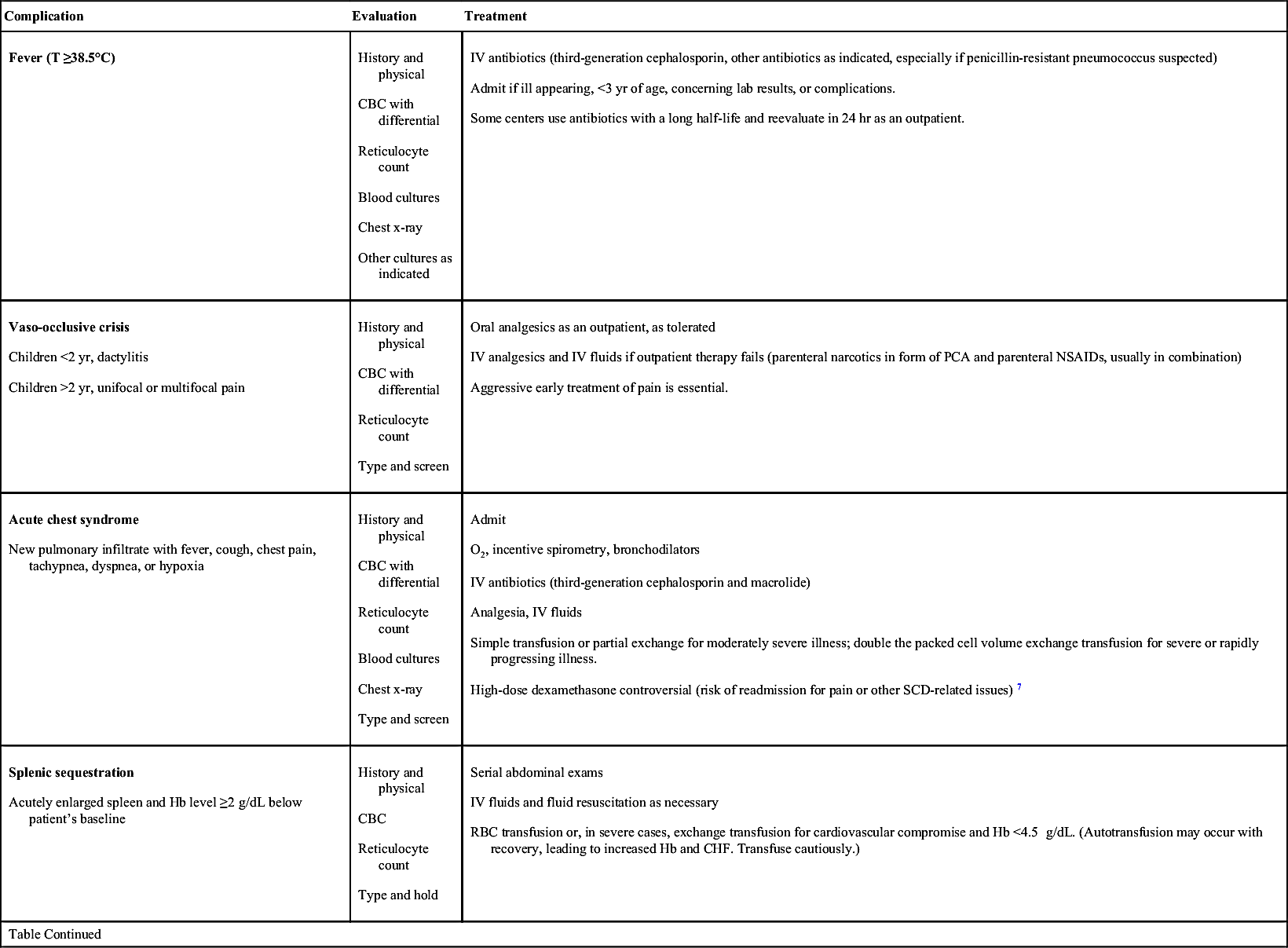

TABLE 14-4

Sickle Cell Disease Complications

| Complication | Evaluation | Treatment |

Fever (T ≥38.5°C) | History and physical CBC with differential Reticulocyte count Blood cultures Chest x-ray Other cultures as indicated | IV antibiotics (third-generation cephalosporin, other antibiotics as indicated, especially if penicillin-resistant pneumococcus suspected) Admit if ill appearing, <3 yr of age, concerning lab results, or complications. Some centers use antibiotics with a long half-life and reevaluate in 24 hr as an outpatient. |

Vaso-occlusive crisis Children <2 yr, dactylitis Children >2 yr, unifocal or multifocal pain | History and physical CBC with differential Reticulocyte count Type and screen | Oral analgesics as an outpatient, as tolerated IV analgesics and IV fluids if outpatient therapy fails (parenteral narcotics in form of PCA and parenteral NSAIDs, usually in combination) Aggressive early treatment of pain is essential. |

Acute chest syndrome New pulmonary infiltrate with fever, cough, chest pain, tachypnea, dyspnea, or hypoxia | History and physical CBC with differential Reticulocyte count Blood cultures Chest x-ray Type and screen | Admit O2, incentive spirometry, bronchodilators IV antibiotics (third-generation cephalosporin and macrolide) Analgesia, IV fluids Simple transfusion or partial exchange for moderately severe illness; double the packed cell volume exchange transfusion for severe or rapidly progressing illness. High-dose dexamethasone controversial (risk of readmission for pain or other SCD-related issues)7 |

Splenic sequestration Acutely enlarged spleen and Hb level ≥2 g/dL below patient’s baseline | History and physical CBC Reticulocyte count Type and hold | Serial abdominal exams IV fluids and fluid resuscitation as necessary RBC transfusion or, in severe cases, exchange transfusion for cardiovascular compromise and Hb <4.5 g/dL. (Autotransfusion may occur with recovery, leading to increased Hb and CHF. Transfuse cautiously.) |

| Table Continued | ||

| Complication | Evaluation | Treatment |

Aplastic crisis Acute illness with Hb below patient’s baseline and low reticulocyte count May follow viral illnesses, especially parvovirus B19 | History and physical CBC with differential Reticulocyte count Type and screen Parvovirus serology and polymerase chain reaction | Admit IV fluids PRBCs for symptomatic anemia Isolation to protect susceptible individuals and women of childbearing age until parvovirus excluded |

Other complications Priapism, CVA, TIA, gallbladder disease, avascular necrosis, hyphema∗ |

NOTE: CVA requires emergency transfusion guided by a hematologist and a neurologist experienced with sickle cell disease. Exchange transfusion preferable to simple transfusion if possible.8

Abbreviations: CBC, Complete blood cell count; CHF, congestive heart failure; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; Hb, hemoglobin; IV, intravenous; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia; PRBCs, packed red blood cells; RBC, red blood cells; SCD, sickle cell disease; T, temperature; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

∗ Hyphema in a patient with sickle cell trait is an ophthalmologic emergency

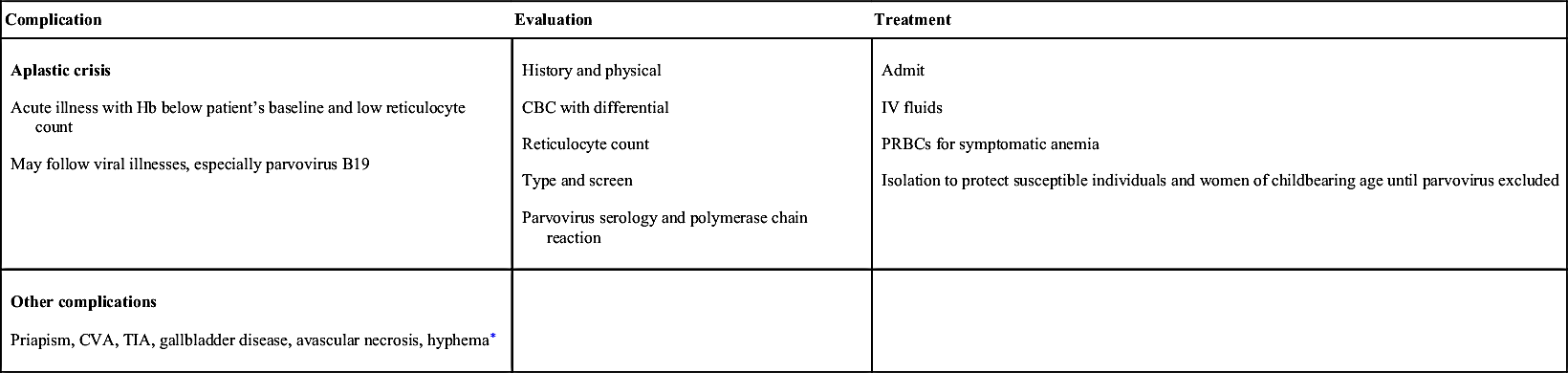

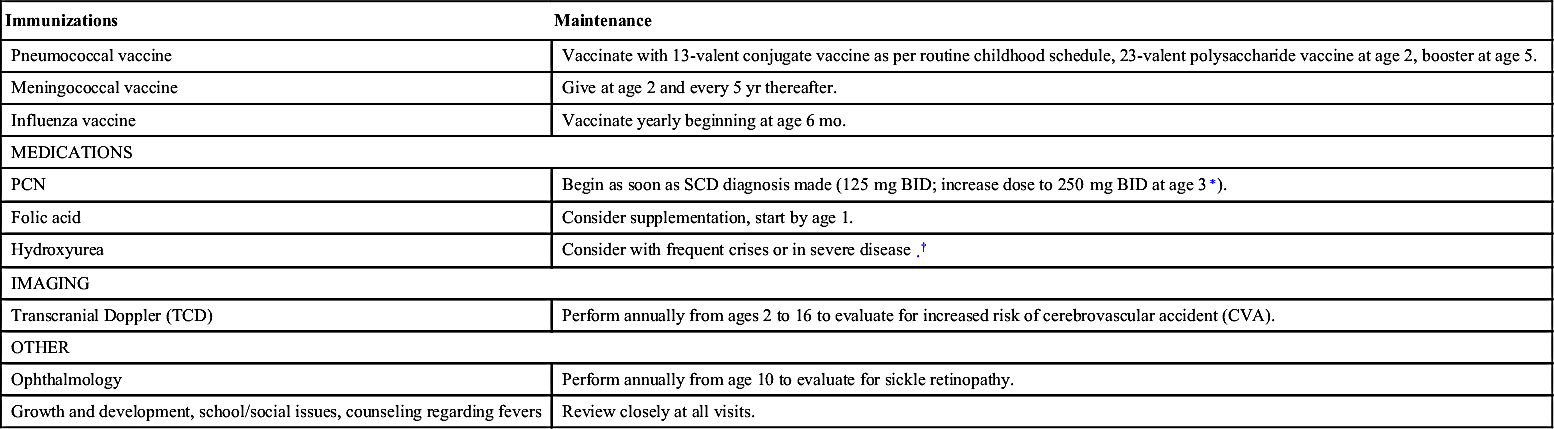

TABLE 14-5

Sickle Cell Disease Health Maintenance

| Immunizations | Maintenance |

| Pneumococcal vaccine | Vaccinate with 13-valent conjugate vaccine as per routine childhood schedule, 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine at age 2, booster at age 5. |

| Meningococcal vaccine | Give at age 2 and every 5 yr thereafter. |

| Influenza vaccine | Vaccinate yearly beginning at age 6 mo. |

| MEDICATIONS | |

| PCN | Begin as soon as SCD diagnosis made (125 mg BID; increase dose to 250 mg BID at age 3∗). |

| Folic acid | Consider supplementation, start by age 1. |

| Hydroxyurea | Consider with frequent crises or in severe disease.† |

| IMAGING | |

| Transcranial Doppler (TCD) | Perform annually from ages 2 to 16 to evaluate for increased risk of cerebrovascular accident (CVA). |

| OTHER | |

| Ophthalmology | Perform annually from age 10 to evaluate for sickle retinopathy. |

| Growth and development, school/social issues, counseling regarding fevers | Review closely at all visits. |

PCN, Penicillin; SCD, sickle cell disease.

∗ Prophylaxis may be discontinued by age 5 if patient has had no prior severe pneumococcal infections or splenectomy and has documented pneumococcal vaccinations, including second 23-valent vaccination. Practice patterns vary. Some continue penicillin indefinitely.

† Increases levels of fetal Hb and decreases HbS polymerization in cells. Has been shown to significantly decrease episodes of vaso-occlusive crises, dactylitis, acute chest syndrome, number of transfusions, and hospitalizations.9,13 May decrease mortality in adults.

III. Neutropenia

IV. Thrombocytopenia

TABLE 14-6

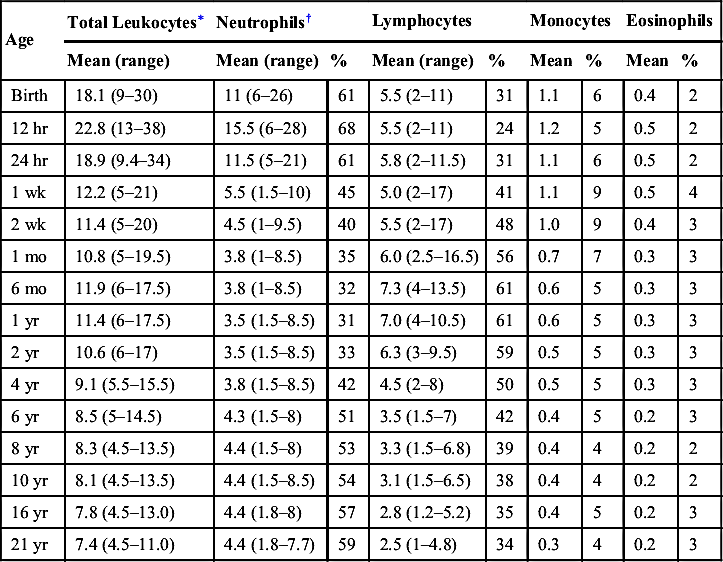

Age-Specific Leukocyte Differential

| Age | Total Leukocytes∗ | Neutrophils† | Lymphocytes | Monocytes | Eosinophils | ||||

| Mean (range) | Mean (range) | % | Mean (range) | % | Mean | % | Mean | % | |

| Birth | 18.1 (9–30) | 11 (6–26) | 61 | 5.5 (2–11) | 31 | 1.1 | 6 | 0.4 | 2 |

| 12 hr | 22.8 (13–38) | 15.5 (6–28) | 68 | 5.5 (2–11) | 24 | 1.2 | 5 | 0.5 | 2 |

| 24 hr | 18.9 (9.4–34) | 11.5 (5–21) | 61 | 5.8 (2–11.5) | 31 | 1.1 | 6 | 0.5 | 2 |

| 1 wk | 12.2 (5–21) | 5.5 (1.5–10) | 45 | 5.0 (2–17) | 41 | 1.1 | 9 | 0.5 | 4 |

| 2 wk | 11.4 (5–20) | 4.5 (1–9.5) | 40 | 5.5 (2–17) | 48 | 1.0 | 9 | 0.4 | 3 |

| 1 mo | 10.8 (5–19.5) | 3.8 (1–8.5) | 35 | 6.0 (2.5–16.5) | 56 | 0.7 | 7 | 0.3 | 3 |

| 6 mo | 11.9 (6–17.5) | 3.8 (1–8.5) | 32 | 7.3 (4–13.5) | 61 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.3 | 3 |

| 1 yr | 11.4 (6–17.5) | 3.5 (1.5–8.5) | 31 | 7.0 (4–10.5) | 61 | 0.6 | 5 | 0.3 | 3 |

| 2 yr | 10.6 (6–17) | 3.5 (1.5–8.5) | 33 | 6.3 (3–9.5) | 59 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.3 | 3 |

| 4 yr | 9.1 (5.5–15.5) | 3.8 (1.5–8.5) | 42 | 4.5 (2–8) | 50 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.3 | 3 |

| 6 yr | 8.5 (5–14.5) | 4.3 (1.5–8) | 51 | 3.5 (1.5–7) | 42 | 0.4 | 5 | 0.2 | 3 |

| 8 yr | 8.3 (4.5–13.5) | 4.4 (1.5–8) | 53 | 3.3 (1.5–6.8) | 39 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.2 | 2 |

| 10 yr | 8.1 (4.5–13.5) | 4.4 (1.5–8.5) | 54 | 3.1 (1.5–6.5) | 38 | 0.4 | 4 | 0.2 | 2 |

| 16 yr | 7.8 (4.5–13.0) | 4.4 (1.8–8) | 57 | 2.8 (1.2–5.2) | 35 | 0.4 | 5 | 0.2 | 3 |

| 21 yr | 7.4 (4.5–11.0) | 4.4 (1.8–7.7) | 59 | 2.5 (1–4.8) | 34 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.2 | 3 |

∗ Numbers of leukocytes are × 103/µL; ranges are estimates of 95% confidence limits; percents refer to differential counts.

† Neutrophils include band cells at all ages and a small number of metamyelocytes and myelocytes in the first few days of life.

Adapted from Cairo MS, Brauho F. Blood and blood-forming tissues. In: Randolph AM, ed. Pediatrics. 21st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003.

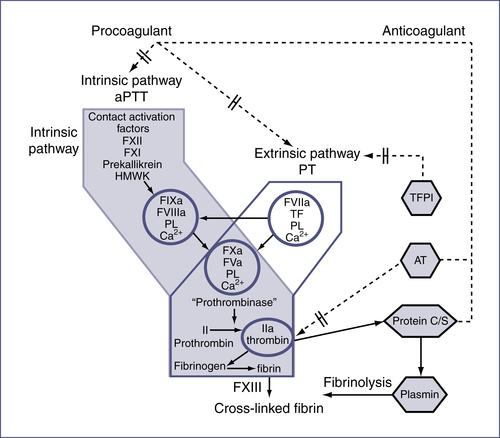

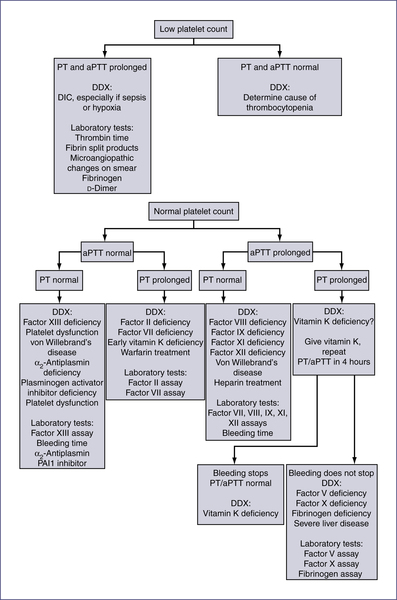

V. Coagulation (Fig. 14-2)

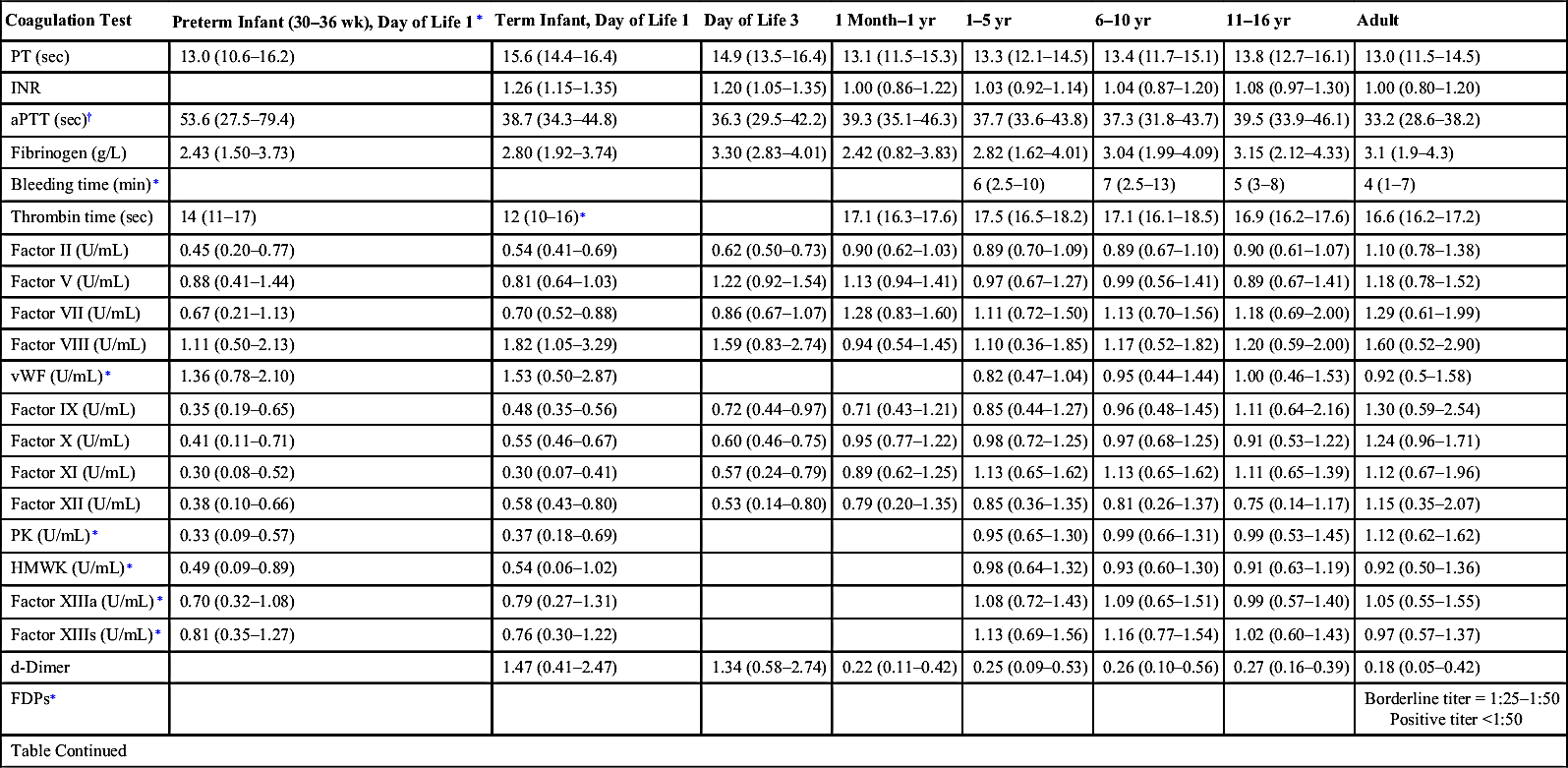

TABLE 14-7

Age-Specific Coagulation Values

| Coagulation Test | Preterm Infant (30–36 wk), Day of Life 1∗ | Term Infant, Day of Life 1 | Day of Life 3 | 1 Month–1 yr | 1–5 yr | 6–10 yr | 11–16 yr | Adult |

| PT (sec) | 13.0 (10.6–16.2) | 15.6 (14.4–16.4) | 14.9 (13.5–16.4) | 13.1 (11.5–15.3) | 13.3 (12.1–14.5) | 13.4 (11.7–15.1) | 13.8 (12.7–16.1) | 13.0 (11.5–14.5) |

| INR | 1.26 (1.15–1.35) | 1.20 (1.05–1.35) | 1.00 (0.86–1.22) | 1.03 (0.92–1.14) | 1.04 (0.87–1.20) | 1.08 (0.97–1.30) | 1.00 (0.80–1.20) | |

| aPTT (sec)† | 53.6 (27.5–79.4) | 38.7 (34.3–44.8) | 36.3 (29.5–42.2) | 39.3 (35.1–46.3) | 37.7 (33.6–43.8) | 37.3 (31.8–43.7) | 39.5 (33.9–46.1) | 33.2 (28.6–38.2) |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 2.43 (1.50–3.73) | 2.80 (1.92–3.74) | 3.30 (2.83–4.01) | 2.42 (0.82–3.83) | 2.82 (1.62–4.01) | 3.04 (1.99–4.09) | 3.15 (2.12–4.33) | 3.1 (1.9–4.3) |

| Bleeding time (min)∗ | 6 (2.5–10) | 7 (2.5–13) | 5 (3–8) | 4 (1–7) | ||||

| Thrombin time (sec) | 14 (11–17) | 12 (10–16)∗ | 17.1 (16.3–17.6) | 17.5 (16.5–18.2) | 17.1 (16.1–18.5) | 16.9 (16.2–17.6) | 16.6 (16.2–17.2) | |

| Factor II (U/mL) | 0.45 (0.20–0.77) | 0.54 (0.41–0.69) | 0.62 (0.50–0.73) | 0.90 (0.62–1.03) | 0.89 (0.70–1.09) | 0.89 (0.67–1.10) | 0.90 (0.61–1.07) | 1.10 (0.78–1.38) |

| Factor V (U/mL) | 0.88 (0.41–1.44) | 0.81 (0.64–1.03) | 1.22 (0.92–1.54) | 1.13 (0.94–1.41) | 0.97 (0.67–1.27) | 0.99 (0.56–1.41) | 0.89 (0.67–1.41) | 1.18 (0.78–1.52) |

| Factor VII (U/mL) | 0.67 (0.21–1.13) | 0.70 (0.52–0.88) | 0.86 (0.67–1.07) | 1.28 (0.83–1.60) | 1.11 (0.72–1.50) | 1.13 (0.70–1.56) | 1.18 (0.69–2.00) | 1.29 (0.61–1.99) |

| Factor VIII (U/mL) | 1.11 (0.50–2.13) | 1.82 (1.05–3.29) | 1.59 (0.83–2.74) | 0.94 (0.54–1.45) | 1.10 (0.36–1.85) | 1.17 (0.52–1.82) | 1.20 (0.59–2.00) | 1.60 (0.52–2.90) |

| vWF (U/mL)∗ | 1.36 (0.78–2.10) | 1.53 (0.50–2.87) | 0.82 (0.47–1.04) | 0.95 (0.44–1.44) | 1.00 (0.46–1.53) | 0.92 (0.5–1.58) | ||

| Factor IX (U/mL) | 0.35 (0.19–0.65) | 0.48 (0.35–0.56) | 0.72 (0.44–0.97) | 0.71 (0.43–1.21) | 0.85 (0.44–1.27) | 0.96 (0.48–1.45) | 1.11 (0.64–2.16) | 1.30 (0.59–2.54) |

| Factor X (U/mL) | 0.41 (0.11–0.71) | 0.55 (0.46–0.67) | 0.60 (0.46–0.75) | 0.95 (0.77–1.22) | 0.98 (0.72–1.25) | 0.97 (0.68–1.25) | 0.91 (0.53–1.22) | 1.24 (0.96–1.71) |

| Factor XI (U/mL) | 0.30 (0.08–0.52) | 0.30 (0.07–0.41) | 0.57 (0.24–0.79) | 0.89 (0.62–1.25) | 1.13 (0.65–1.62) | 1.13 (0.65–1.62) | 1.11 (0.65–1.39) | 1.12 (0.67–1.96) |

| Factor XII (U/mL) | 0.38 (0.10–0.66) | 0.58 (0.43–0.80) | 0.53 (0.14–0.80) | 0.79 (0.20–1.35) | 0.85 (0.36–1.35) | 0.81 (0.26–1.37) | 0.75 (0.14–1.17) | 1.15 (0.35–2.07) |

| PK (U/mL)∗ | 0.33 (0.09–0.57) | 0.37 (0.18–0.69) | 0.95 (0.65–1.30) | 0.99 (0.66–1.31) | 0.99 (0.53–1.45) | 1.12 (0.62–1.62) | ||

| HMWK (U/mL)∗ | 0.49 (0.09–0.89) | 0.54 (0.06–1.02) | 0.98 (0.64–1.32) | 0.93 (0.60–1.30) | 0.91 (0.63–1.19) | 0.92 (0.50–1.36) | ||

| Factor XIIIa (U/mL)∗ | 0.70 (0.32–1.08) | 0.79 (0.27–1.31) | 1.08 (0.72–1.43) | 1.09 (0.65–1.51) | 0.99 (0.57–1.40) | 1.05 (0.55–1.55) | ||

| Factor XIIIs (U/mL)∗ | 0.81 (0.35–1.27) | 0.76 (0.30–1.22) | 1.13 (0.69–1.56) | 1.16 (0.77–1.54) | 1.02 (0.60–1.43) | 0.97 (0.57–1.37) | ||

| d-Dimer | 1.47 (0.41–2.47) | 1.34 (0.58–2.74) | 0.22 (0.11–0.42) | 0.25 (0.09–0.53) | 0.26 (0.10–0.56) | 0.27 (0.16–0.39) | 0.18 (0.05–0.42) | |

| FDPs∗ | Borderline titer = 1:25–1:50 Positive titer <1:50 | |||||||

| Table Continued | ||||||||

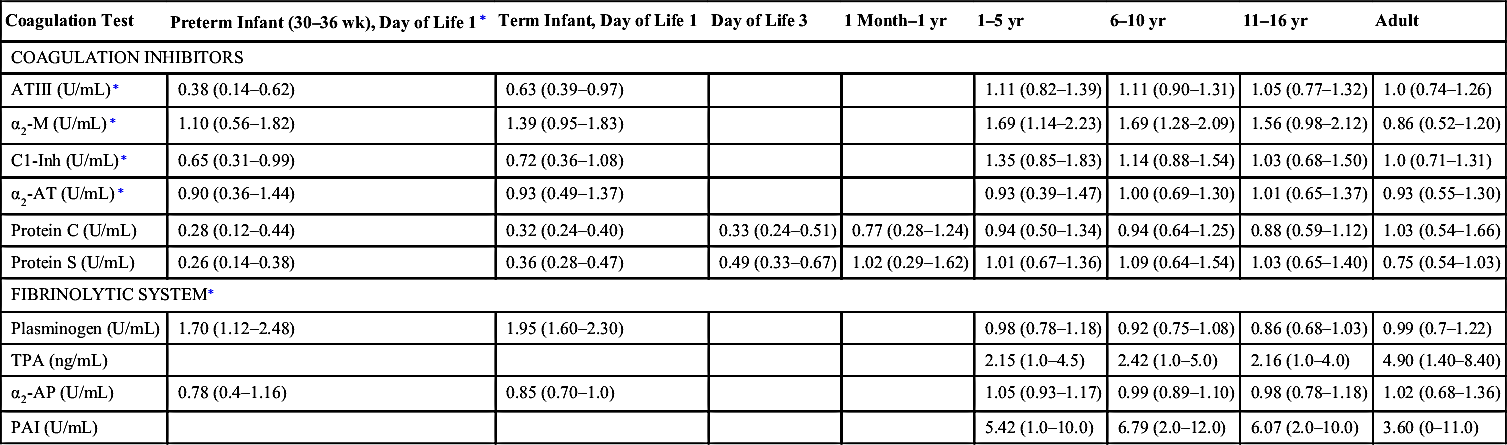

| Coagulation Test | Preterm Infant (30–36 wk), Day of Life 1∗ | Term Infant, Day of Life 1 | Day of Life 3 | 1 Month–1 yr | 1–5 yr | 6–10 yr | 11–16 yr | Adult |

| COAGULATION INHIBITORS | ||||||||

| ATIII (U/mL)∗ | 0.38 (0.14–0.62) | 0.63 (0.39–0.97) | 1.11 (0.82–1.39) | 1.11 (0.90–1.31) | 1.05 (0.77–1.32) | 1.0 (0.74–1.26) | ||

| α2-M (U/mL)∗ | 1.10 (0.56–1.82) | 1.39 (0.95–1.83) | 1.69 (1.14–2.23) | 1.69 (1.28–2.09) | 1.56 (0.98–2.12) | 0.86 (0.52–1.20) | ||

| C1-Inh (U/mL)∗ | 0.65 (0.31–0.99) | 0.72 (0.36–1.08) | 1.35 (0.85–1.83) | 1.14 (0.88–1.54) | 1.03 (0.68–1.50) | 1.0 (0.71–1.31) | ||

| α2-AT (U/mL)∗ | 0.90 (0.36–1.44) | 0.93 (0.49–1.37) | 0.93 (0.39–1.47) | 1.00 (0.69–1.30) | 1.01 (0.65–1.37) | 0.93 (0.55–1.30) | ||

| Protein C (U/mL) | 0.28 (0.12–0.44) | 0.32 (0.24–0.40) | 0.33 (0.24–0.51) | 0.77 (0.28–1.24) | 0.94 (0.50–1.34) | 0.94 (0.64–1.25) | 0.88 (0.59–1.12) | 1.03 (0.54–1.66) |

| Protein S (U/mL) | 0.26 (0.14–0.38) | 0.36 (0.28–0.47) | 0.49 (0.33–0.67) | 1.02 (0.29–1.62) | 1.01 (0.67–1.36) | 1.09 (0.64–1.54) | 1.03 (0.65–1.40) | 0.75 (0.54–1.03) |

| FIBRINOLYTIC SYSTEM∗ | ||||||||

| Plasminogen (U/mL) | 1.70 (1.12–2.48) | 1.95 (1.60–2.30) | 0.98 (0.78–1.18) | 0.92 (0.75–1.08) | 0.86 (0.68–1.03) | 0.99 (0.7–1.22) | ||

| TPA (ng/mL) | 2.15 (1.0–4.5) | 2.42 (1.0–5.0) | 2.16 (1.0–4.0) | 4.90 (1.40–8.40) | ||||

| α2-AP (U/mL) | 0.78 (0.4–1.16) | 0.85 (0.70–1.0) | 1.05 (0.93–1.17) | 0.99 (0.89–1.10) | 0.98 (0.78–1.18) | 1.02 (0.68–1.36) | ||

| PAI (U/mL) | 5.42 (1.0–10.0) | 6.79 (2.0–12.0) | 6.07 (2.0–10.0) | 3.60 (0–11.0) | ||||

α2-AP, α2-Antiplasmin; α2-AT, α2-antitrypsin; α2-M, α2-macroglobulin; aPTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; ATIII, antithrombin III; FDPs, fibrin degradation products; HMWK, high-molecular-weight kininogen; INR, international normalized ratio; PAI, plasminogen activator inhibitor; PK, prekallikrein; PT, prothrombin time; TPA, tissue plasminogen activator; VIII, factor VIII procoagulant; vWF, von Willebrand factor.

∗ Data from Andrew M, Paes B, Milner R, et al. Development of the human anticoagulant system in the healthy premature infant. Blood. 1987;70:165-172; Andrew M, Paes B, Milner R, et al. Development of the human anticoagulant system in the healthy premature infant. Blood. 1988;72:1651-1657; and Andrew M, Vegh P, Johnston M, et al. Maturation of the hemostatic system during childhood. Blood. 1992;8:1998-2005.

† aPTT values may vary depending on reagent.

Adapted from Monagle P, Barnes C, Ignjatovic, V, et al. Developmental haemostasis. Impact for clinical haemostasis laboratories. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95;362-372.

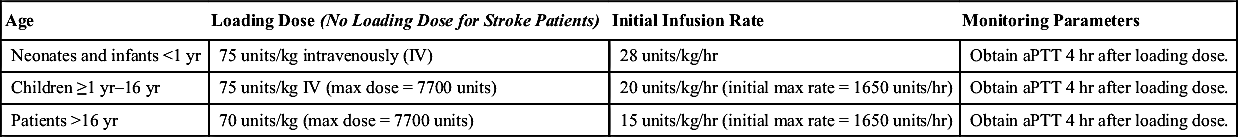

TABLE 14-8

Unfractionated Heparin Dose Initiation Guidelines for Goal aPTT Range of 50–80 Seconds∗

| Age | Loading Dose (No Loading Dose for Stroke Patients) | Initial Infusion Rate | Monitoring Parameters |

| Neonates and infants <1 yr | 75 units/kg intravenously (IV) | 28 units/kg/hr | Obtain aPTT 4 hr after loading dose. |

| Children ≥1 yr–16 yr | 75 units/kg IV (max dose = 7700 units) | 20 units/kg/hr (initial max rate = 1650 units/hr) | Obtain aPTT 4 hr after loading dose. |

| Patients >16 yr | 70 units/kg (max dose = 7700 units) | 15 units/kg/hr (initial max rate = 1650 units/hr) | Obtain aPTT 4 hr after loading dose. |

∗ Reflects antifactor Xa level of 0.3–0.7 IU/mL with current activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) reagents at Johns Hopkins Hospital 2/3/11. Therapeutic aPTT range may vary with different aPTT reagents.

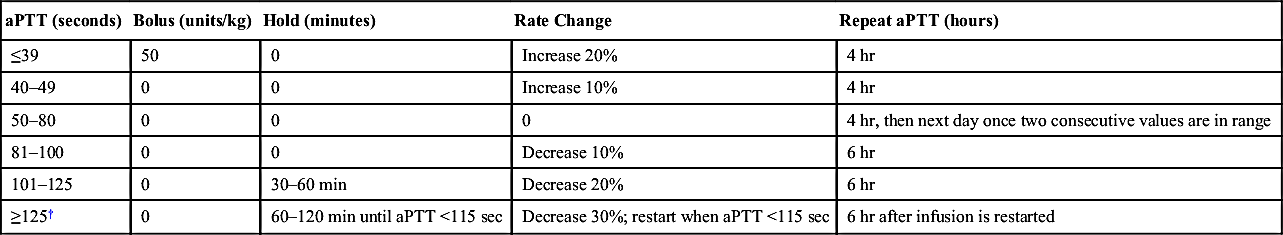

TABLE 14-9

Unfractionated Heparin Dose Adjustment Algorithm for Goal aPTT Range of 50–80 Seconds∗

| aPTT (seconds) | Bolus (units/kg) | Hold (minutes) | Rate Change | Repeat aPTT (hours) |

| ≤39 | 50 | 0 | Increase 20% | 4 hr |

| 40–49 | 0 | 0 | Increase 10% | 4 hr |

| 50–80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 hr, then next day once two consecutive values are in range |

| 81–100 | 0 | 0 | Decrease 10% | 6 hr |

| 101–125 | 0 | 30–60 min | Decrease 20% | 6 hr |

| ≥125† | 0 | 60–120 min until aPTT <115 sec | Decrease 30%; restart when aPTT <115 sec | 6 hr after infusion is restarted |

∗ Reflects antifactor Xa level of 0.3–0.7 IU/mL with current activated partial thromboplastin (aPTT) reagents at Johns Hopkins Hospital 2/3/11. Therapeutic aPTT range may vary with different aPTT reagents.

† Confirm that specimen was not drawn from heparinized line or same extremity as site of heparin infusion.

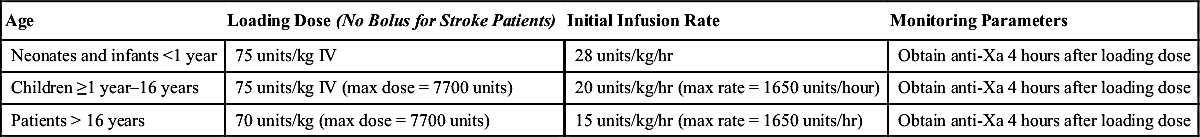

TABLE 14-10

Unfractionated Heparin Dose Initiation Guidelines For Goal Anti-Xa Activity of 0.3-0.7 Units/ML

| Age | Loading Dose (No Bolus for Stroke Patients) | Initial Infusion Rate | Monitoring Parameters |

| Neonates and infants <1 year | 75 units/kg IV | 28 units/kg/hr | Obtain anti-Xa 4 hours after loading dose |

| Children ≥1 year–16 years | 75 units/kg IV (max dose = 7700 units) | 20 units/kg/hr (max rate = 1650 units/hour) | Obtain anti-Xa 4 hours after loading dose |

| Patients > 16 years | 70 units/kg (max dose = 7700 units) | 15 units/kg/hr (max rate = 1650 units/hr) | Obtain anti-Xa 4 hours after loading dose |

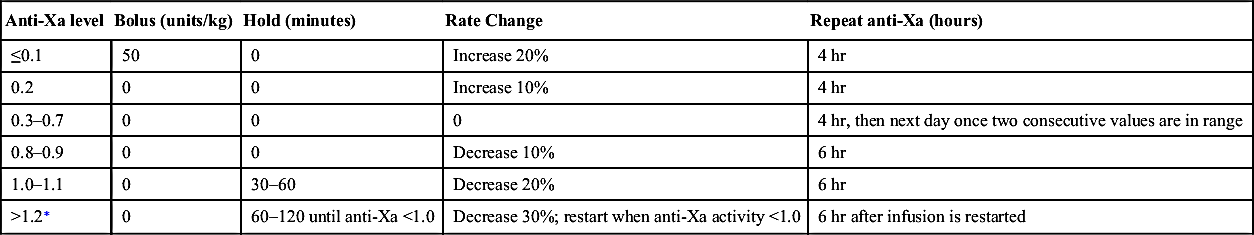

TABLE 14-11

Unfractionated Heparin Dose Adjustment Algorithm For Goal Anti-Xa Activity of 0.3–0.7 Units/ML

| Anti-Xa level | Bolus (units/kg) | Hold (minutes) | Rate Change | Repeat anti-Xa (hours) |

| ≤0.1 | 50 | 0 | Increase 20% | 4 hr |

| 0.2 | 0 | 0 | Increase 10% | 4 hr |

| 0.3–0.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 hr, then next day once two consecutive values are in range |

| 0.8–0.9 | 0 | 0 | Decrease 10% | 6 hr |

| 1.0–1.1 | 0 | 30–60 | Decrease 20% | 6 hr |

| >1.2∗ | 0 | 60–120 until anti-Xa <1.0 | Decrease 30%; restart when anti-Xa activity <1.0 | 6 hr after infusion is restarted |

∗ Confirm that specimen was not drawn from heparinized line or same extremity as site of heparin infusion.

TABLE 14-12

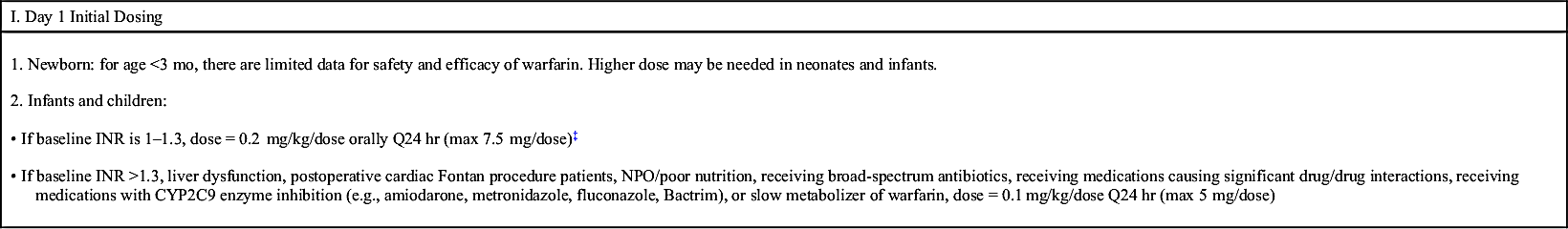

Adjustment and Monitoring of Warfarin to Maintain an International Normalized Ratio (INR) Between 2 and 3∗,11

| I. Day 1 Initial Dosing |

1. Newborn: for age <3 mo, there are limited data for safety and efficacy of warfarin. Higher dose may be needed in neonates and infants. 2. Infants and children: • If baseline INR is 1–1.3, dose = 0.2 mg/kg/dose orally Q24 hr (max 7.5 mg/dose)‡ • If baseline INR >1.3, liver dysfunction, postoperative cardiac Fontan procedure patients, NPO/poor nutrition, receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics, receiving medications causing significant drug/drug interactions, receiving medications with CYP2C9 enzyme inhibition (e.g., amiodarone, metronidazole, fluconazole, Bactrim), or slow metabolizer of warfarin, dose = 0.1 mg/kg/dose Q24 hr (max 5 mg/dose) |

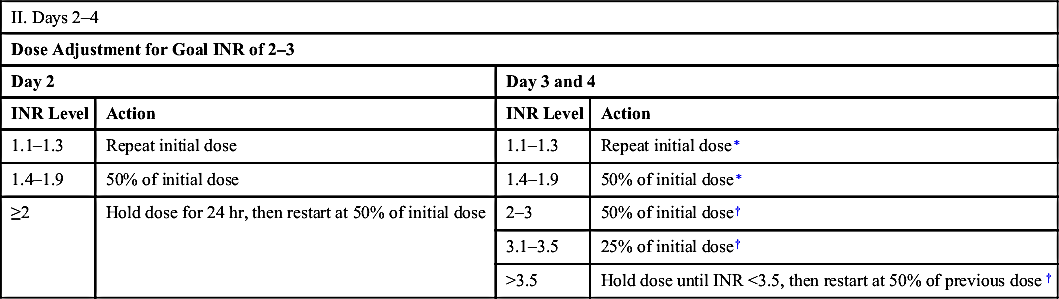

| II. Days 2–4 | |||

| Dose Adjustment for Goal INR of 2–3 | |||

| Day 2 | Day 3 and 4 | ||

| INR Level | Action | INR Level | Action |

| 1.1–1.3 | Repeat initial dose | 1.1–1.3 | Repeat initial dose∗ |

| 1.4–1.9 | 50% of initial dose | 1.4–1.9 | 50% of initial dose∗ |

| ≥2 | Hold dose for 24 hr, then restart at 50% of initial dose | 2–3 | 50% of initial dose† |

| 3.1–3.5 | 25% of initial dose† | ||

| >3.5 | Hold dose until INR <3.5, then restart at 50% of previous dose† | ||

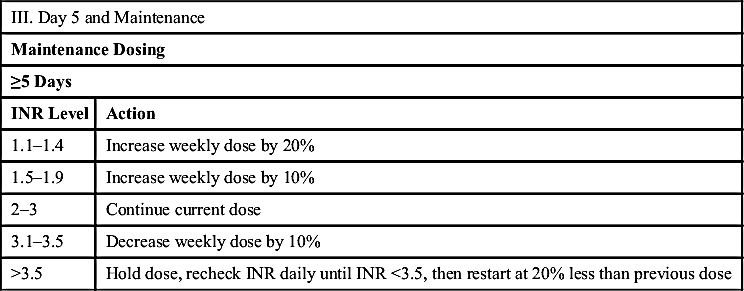

| III. Day 5 and Maintenance | |

| Maintenance Dosing | |

| ≥5 Days | |

| INR Level | Action |

| 1.1–1.4 | Increase weekly dose by 20% |

| 1.5–1.9 | Increase weekly dose by 10% |

| 2–3 | Continue current dose |

| 3.1–3.5 | Decrease weekly dose by 10% |

| >3.5 | Hold dose, recheck INR daily until INR <3.5, then restart at 20% less than previous dose |

∗ If INR is not >1.5 on day 4, patient should be reassessed, and dose/kg should be adjusted on an individual basis.

† Consult pediatric hematology for patient-specific recommendations on reduced dosing.

‡ Reported average daily dose to maintain INR of 2–3 for infants is 0.33 mg/kg; for adolescents, 0.09 mg/kg; and for adults, from 0.04–0.08 mg/kg.

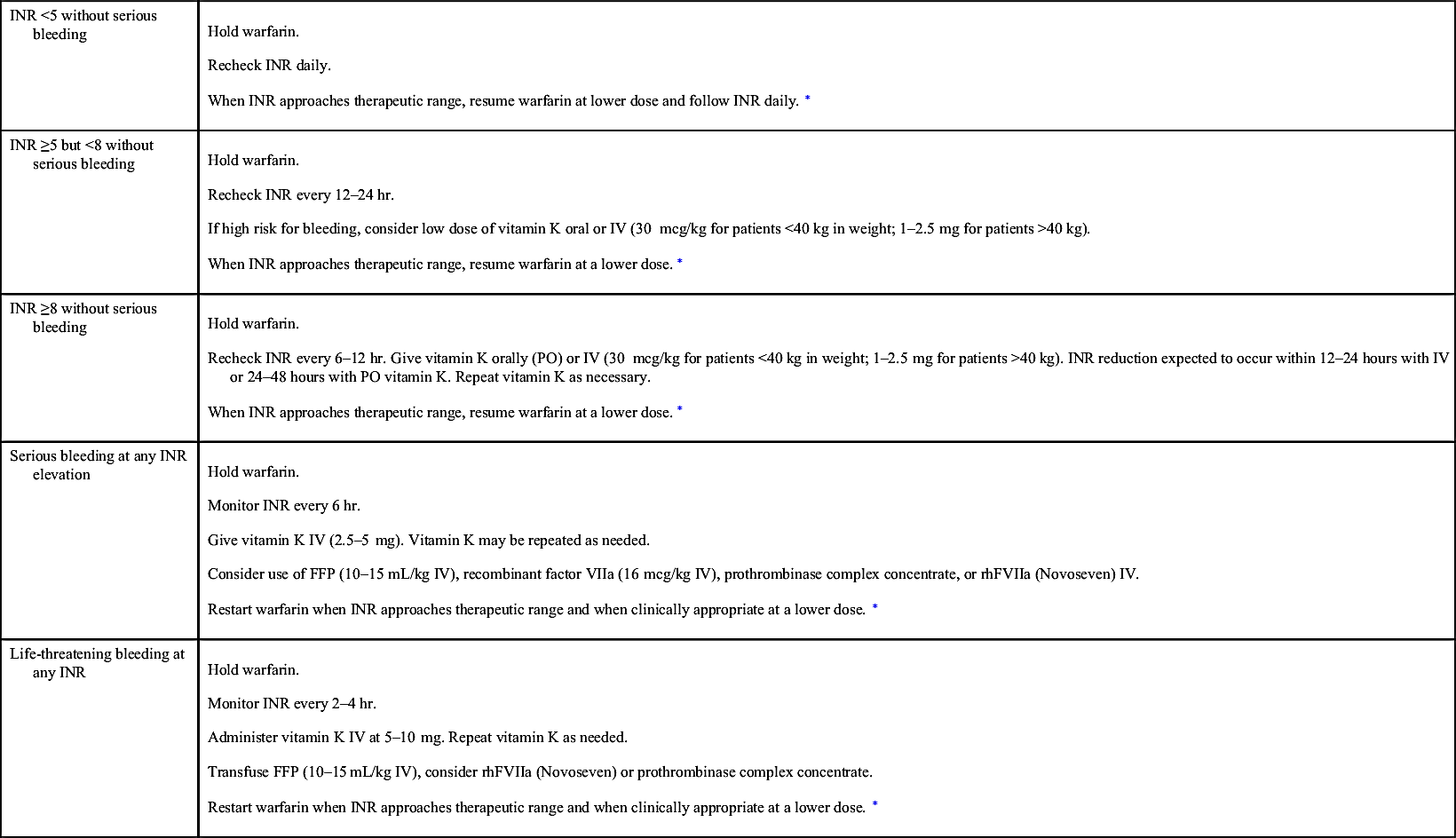

TABLE 14-13

Management of Excessive Warfarin Anticoagulation

| INR <5 without serious bleeding | Hold warfarin. Recheck INR daily. When INR approaches therapeutic range, resume warfarin at lower dose and follow INR daily.∗ |

| INR ≥5 but <8 without serious bleeding | Hold warfarin. Recheck INR every 12–24 hr. If high risk for bleeding, consider low dose of vitamin K oral or IV (30 mcg/kg for patients <40 kg in weight; 1–2.5 mg for patients >40 kg). When INR approaches therapeutic range, resume warfarin at a lower dose.∗ |

| INR ≥8 without serious bleeding | Hold warfarin. Recheck INR every 6–12 hr. Give vitamin K orally (PO) or IV (30 mcg/kg for patients <40 kg in weight; 1–2.5 mg for patients >40 kg). INR reduction expected to occur within 12–24 hours with IV or 24–48 hours with PO vitamin K. Repeat vitamin K as necessary. When INR approaches therapeutic range, resume warfarin at a lower dose.∗ |

| Serious bleeding at any INR elevation | Hold warfarin. Monitor INR every 6 hr. Give vitamin K IV (2.5–5 mg). Vitamin K may be repeated as needed. Consider use of FFP (10–15 mL/kg IV), recombinant factor VIIa (16 mcg/kg IV), prothrombinase complex concentrate, or rhFVIIa (Novoseven) IV. Restart warfarin when INR approaches therapeutic range and when clinically appropriate at a lower dose.∗ |

| Life-threatening bleeding at any INR | Hold warfarin. Monitor INR every 2–4 hr. Administer vitamin K IV at 5–10 mg. Repeat vitamin K as needed. Transfuse FFP (10–15 mL/kg IV), consider rhFVIIa (Novoseven) or prothrombinase complex concentrate. Restart warfarin when INR approaches therapeutic range and when clinically appropriate at a lower dose.∗ |

NOTE: Always evaluate for bleeding risks and potential drug interactions.

FFP, Fresh frozen plasma; INR, international normalized ratio; IV, intravenous; rhVIIa, activated recombinant human factor VII.

∗ Refer to Table 14-12.

VI. Blood Component Replacement

TABLE 14-14

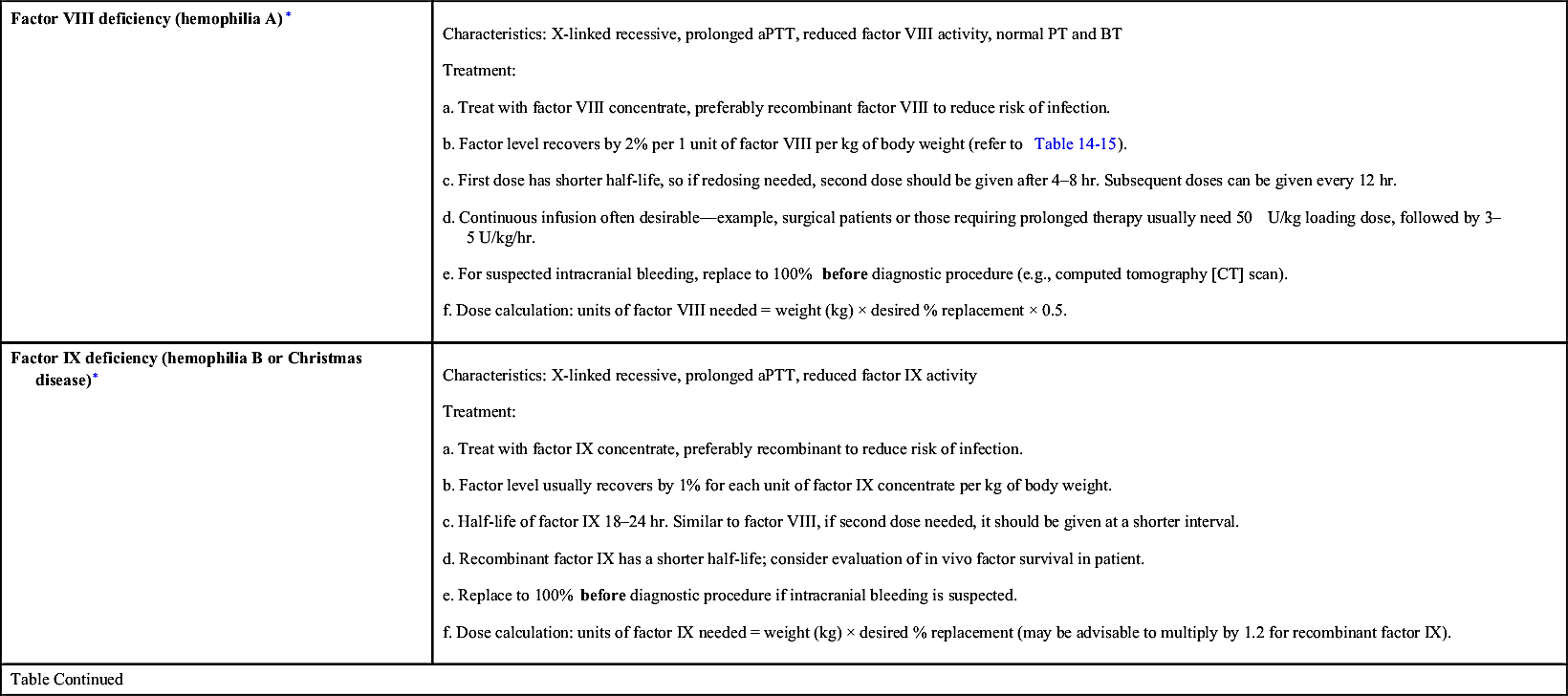

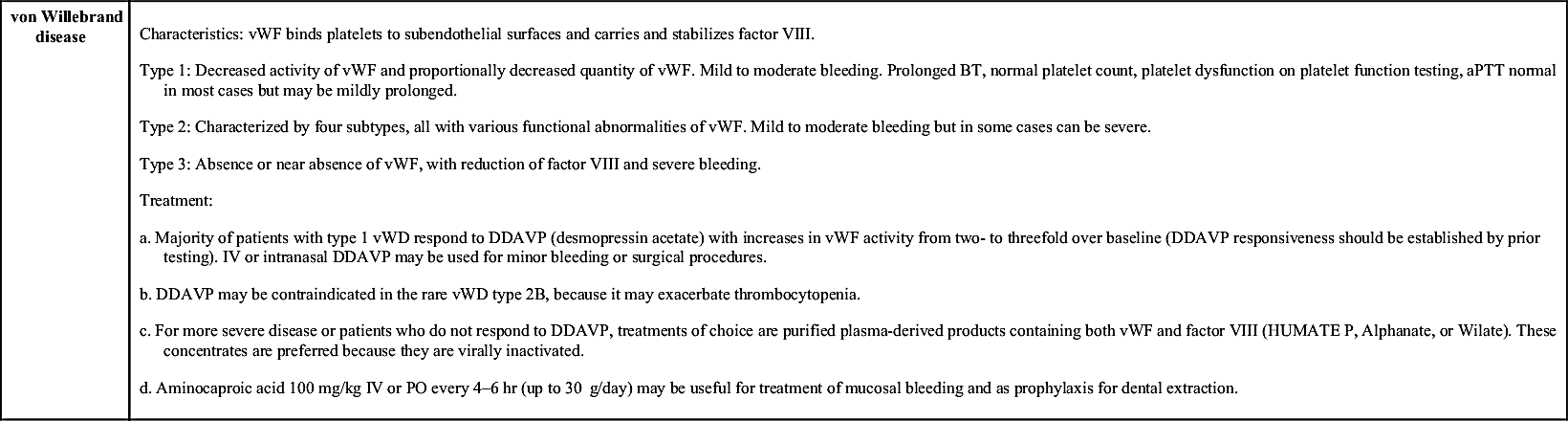

| Factor VIII deficiency (hemophilia A)∗ | Characteristics: X-linked recessive, prolonged aPTT, reduced factor VIII activity, normal PT and BT Treatment: a. Treat with factor VIII concentrate, preferably recombinant factor VIII to reduce risk of infection. b. Factor level recovers by 2% per 1 unit of factor VIII per kg of body weight (refer to Table 14-15). c. First dose has shorter half-life, so if redosing needed, second dose should be given after 4–8 hr. Subsequent doses can be given every 12 hr. d. Continuous infusion often desirable—example, surgical patients or those requiring prolonged therapy usually need 50 U/kg loading dose, followed by 3–5 U/kg/hr. e. For suspected intracranial bleeding, replace to 100% before diagnostic procedure (e.g., computed tomography [CT] scan). f. Dose calculation: units of factor VIII needed = weight (kg) × desired % replacement × 0.5. |

| Factor IX deficiency (hemophilia B or Christmas disease)∗ | Characteristics: X-linked recessive, prolonged aPTT, reduced factor IX activity Treatment: a. Treat with factor IX concentrate, preferably recombinant to reduce risk of infection. b. Factor level usually recovers by 1% for each unit of factor IX concentrate per kg of body weight. c. Half-life of factor IX 18–24 hr. Similar to factor VIII, if second dose needed, it should be given at a shorter interval. d. Recombinant factor IX has a shorter half-life; consider evaluation of in vivo factor survival in patient. e. Replace to 100% before diagnostic procedure if intracranial bleeding is suspected. f. Dose calculation: units of factor IX needed = weight (kg) × desired % replacement (may be advisable to multiply by 1.2 for recombinant factor IX). |

| Table Continued | |

aPTT, Activated partial thromboplastin time; BT, bleeding time; IV, intravenous; PO, per os; PT, prothrombin time; vWF, von Willebrand factor

.

∗ All patients with hemophilia should be vaccinated with hepatitis A and B vaccines.

TABLE 14-15

Desired Factor Replacement in Hemophilia

| Bleeding Site | Desired Level (%) |

| Minor soft tissue bleeding | 20–30 |

| Joint | 40–70 |

| Simple dental extraction | 50 |

| Major soft tissue bleeding | 80–100 |

| Serious oral bleeding | 80–100 |

| Head injury | 100+ |

| Major surgery (dental, orthopedic, other) | 100+ |

NOTE: A hematologist should be consulted for all major bleeding and before surgery.

Round to the nearest vial; do not exceed 200%.