Understanding and Designing Organizational Structures

Abstract

This chapter explains key concepts related to organizational structures and provides information on designing effective structures. This information can be used to help nurse managers and baccalaureate-prepared nurses function in an organization and to design structures that support work processes. An underlying theme is designing organizational structures that will respond to the continuous changes taking place in the healthcare environment.

• Analyze the relationships among mission, vision, and philosophy statements and organizational structure.

• Analyze factors that influence the design of an organizational structure.

• Compare and contrast the major types of organizational structures.

• Describe the differences between redesigning, restructuring, and reengineering of organizational systems.

Key Terms

accountable care organization

bureaucracy

chain of command

flat organizational structure

functional structure

hierarchy

hybrid

line function

matrix structure

mission

organization

organizational chart

organizational culture

organizational structure

organizational theory

philosophy

redesign

reengineering

restructuring

service-line structures

shared governance

span of control

staff function

system

systems theory

vision

Introduction

Since time began, people have organized themselves into groups. The term organization has multiple meanings. It can refer to a business structure designed to support specific business goals and processes, or it can refer to a group of individuals working together to achieve a common purpose. Regardless of how the term is used, learning to determine how an organization accomplishes its work, how to operate productively within an organization, and how to influence organizational processes is essential to a successful professional nursing practice.

Organizational theory (sometimes called organizational studies) is the systematic analysis of how organizations and their component parts act and interact. Organizational theory is based largely on the systematic investigation of the effectiveness of specific organizational designs in achieving their purpose. Organizational theory development is a process of creating knowledge to understand the effect of identified factors, such as (1) organizational culture; (2) organizational technology, which is defined as all the work being carried out; and (3) organizational structure or organizational development. A purpose of such work is to determine how organizational effectiveness might be predicted or controlled through the design of the organizational structure.

Specific organizational theories provide insight into areas such as effective organizational structures, motivation of employees, decision-making, and leadership. A common framework in health care for analysis and application of organizational theory is systems theory. A system is an interacting collection of components or parts that together make up an integrated whole. The basic tenet of systems theory is that the individual components of any system interact with each other and with their environment. To be effective, baccalaureate-prepared nurses need to understand the specific part—role and function—they play within a system and how they interact, influence, and are influenced by other parts of the system.

An organization’s mission, vision, and philosophy form the foundation for its structure and performance as well as the development of the professional practice models it uses. An organization’s mission, or reason for the organization’s existence, influences the design of the structure (e.g., to meet the healthcare needs of a designated population, to provide supportive and stabilizing care to an acute care population, or to prepare patients for a peaceful death). The vision is the articulated goal to which the organization aspires. A vision statement conveys an inspirational view of how the organization wishes to be described at some future time. It suggests how far to strive in all endeavors. Another key factor influencing structure is the organization’s philosophy. A philosophy expresses the values and beliefs that members of the organization hold about the nature of their work, about the people to whom they provide service, and about themselves and others providing the services.

Mission

The mission statement defines the organization’s reason or purpose for being. The mission statement identifies the organization’s customers (individuals, families, populations, or communities) and the types of services offered, such as outreach, comprehensive care management, acute care, rehabilitation, or home care. It enacts the vision statement.

The mission statement sets the stage by defining the services to be offered, which, in turn, identify the kinds of technologies and human resources to be employed. The mission statement of accountable care organizations (a group of providers and healthcare organizations who are organized to give comprehensive, coordinated care focused on improving patient outcomes) are focused on providing comprehensive coordinated care in order to improve the health and well-being of a group of individuals. An example of a mission statement appears in Box 8-1. Hospitals’ missions are primarily treatment-oriented; the missions of ambulatory care group practices combine treatment, prevention, and diagnosis-oriented services; long-term care facilities’ missions are primarily maintenance and social support–oriented; and the missions of nursing centers are oriented toward promoting optimal health status for a defined group of people. The definition of services to be provided and the implications for technologies and human resources greatly influence the design of the organizational structure, that is, the arrangement of the work group.

Nursing, as a profession providing a service within a healthcare agency, formulates its own mission statement that describes its contributions to achieve the agency’s mission. One of the purposes of the nursing profession is to provide nursing care to patients. The statement should define nursing based on theories that form the basis for the model of nursing to be used in guiding the process of nursing care delivery. Nursing’s mission statement tells why nursing exists within the context of the organization. This statement is written so that others within the organization can know and understand nursing’s role in achieving the agency’s mission. The mission should be the guiding framework for decision making. It should be known and understood by other healthcare professionals, by patients and their families, and by the community. It indicates the relationships among nurses and patients, other personnel in the organization, the community, as well as health and illness. The mission provides direction for the evolving statement of philosophy and the organizational structure. It should be reviewed for accuracy and updated routinely. Various work units that provide specific services such as intensive care, women’s health services, or hospice care may also formulate mission statements that detail their specific contributions to the overall organization.

Vision

Vision statements are future-oriented, purposeful statements designed to identify the desired future of an organization. They serve to unify all subsequent statements toward the view of the future and to convey the core message of the mission statement. Typically, vision statements are brief, consisting of only one or two phrases or sentences. An example of a vision statement is provided in Box 8-1.

Philosophy

A philosophy is a written statement that articulates the values and beliefs held about the nature of the work required to accomplish the mission and the nature and rights of both the people being served and those providing the service. A nursing philosophy states the vision of what nursing practice should be within the organization and how it contributes to the health of individuals and communities. For example, the organization’s mission statement may incorporate the provision of individualized care as an organizational purpose. The philosophy statement would then support this purpose through an expression of a belief in the responsibility of nursing staff to act as patient advocates and to provide quality care according to the wishes of the patient, family, and significant others.

Philosophies are evolutionary in that they are shaped both by the social environment and by the stage of development of professionals delivering the service. Nursing staff reflect the values of their time. The values acquired through education are reflected in the nursing philosophy. Philosophies require updating to reflect the extension of rights brought about by such changes. Box 8-1 shows an example of a philosophy developed for a neurosurgical unit.

Organizational Culture

An organization’s mission, vision, and philosophy both shape and reflect organizational culture. Organizational culture is the reflection of the norms or traditions of the organization and is exemplified by behaviors that illustrate values and beliefs. Examples include rituals and customary forms of practice, such as celebrations of promotions, degree attainment, professional performance, weddings, and retirements. Other examples of norms that reflect organizational culture are the characteristics of the people who are recognized as heroes by the organization and the behaviors—either positive or negative—that are accepted or tolerated within the organization.

In organizations, culture is demonstrated in two ways that can be either mutually reinforcing or conflict-producing. Organizational culture is typically expressed in a formal manner via written mission, vision, and philosophy statements; job descriptions; and policies and procedures. Beyond formal documents and verbal descriptions given by administrators and managers, organizational culture is also represented in the day-to-day experience of staff and patients. To many, it is the lived experience that reflects the true organizational culture. Do the decisions that are made within the organization consistently demonstrate that the organization values its patients and keeps their needs at the forefront? Are the employees treated with trust and respect, or are the words used in recruitment ads simply empty promises with little evidence to back them up? When a lack of congruity exists between the expressed organizational culture and the experienced organizational culture, confusion, frustration, and poor morale often result (Casida and Parker, 2011; Tsai, 2011).

Organizational culture can be effective and promote success and positive outcomes, or it can be ineffective and result in disharmony, dissatisfaction, and poor outcomes for patients, staff, and the organization. A number of workplace variables are influenced by organizational culture. When seeking employment or advancement, nurses need to assess the organization’s culture and develop a clear understanding of existing expectations as well as the formal and informal communication patterns. Various techniques and tools are available to assist the nurse in performing a cultural assessment of an organization (Cummings, Midodzi, Wong, & Estabrooks, 2010). With a solid understanding of organizational culture, nurses will be better able to be effective change agents and help transform the organizations in which they work. The Research Perspective presents a study on the effect of authentic leadership and structural empowerment on the emotional exhaustion and cynicism of new graduates and experienced nurses.

Factors Influencing Organizational Development

To be most effective, organizational structures must reflect the organization’s mission, vision, philosophy, goals, and objectives. Organizational structure defines how work is organized, where decisions are made, and the authority and responsibility of workers. It provides a map for communication and outlines decision-making paths. As organizations change through acquisitions and mergers, it is essential that structure changes to accomplish revised missions.

Probably the best theory to explain today’s nursing organizational development is chaos (complexity, nonlinear, quantum) theory. (See Chaos Theory in the Index.) In essence, chaos theory suggests that lives—and organizations—are web-like. Pulling on one small segment rearranges the web, a new pattern emerges, and yet the whole remains. This theory, applied to nursing organizations, suggests that differences logically exist between and among various organizations and that the constant environmental forces continue to affect the structure, its functioning, and the services. See the Theory Box for Chapter 7, p. 132.

Ongoing changes in the U.S. healthcare delivery system, such as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (http://housedocs.house.gov/energycommerce/ppacacon.pdf), revise reimbursement regulation and develop networks for delivery of health care. These modifications have profound effects on organizational structure designs. Consumerism, the consumer demand that care be customized to meet individual needs, necessitates that decision making be done where the care is delivered. Increased consumer knowledge and greater responsibility for selecting healthcare providers and options have resulted in consumers who demand immediate access to customized care. Information from Internet sources and direct-to-consumer advertising are significantly altering the expectation and behaviors of healthcare consumers. For example, Hospital Compare (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov) is a tool that consumers can use to access a searchable database of information describing how well hospitals care for patients with certain medical and surgical conditions. Access to this information allows consumers to make informed decisions about where they seek their health care. In response to consumer expectations, facilities concentrate on consumer satisfaction and delivery of patient-focused care. Changes in both facility design and care delivery systems are likely to continue as efforts are made to reduce cost while still striving to meet or exceed consumer expectations and improve patient outcomes.

Competition for patients is another factor influencing structure design. These three factors—change including federal mandates, consumerism, and competition—necessitate reengineering healthcare structures. Whereas redesign is a technique to analyze tasks to improve efficiency (e.g., identifying the most efficient flow of supplies to a nursing unit) and restructuring is a technique to enhance organizational productivity (e.g., identifying the most appropriate type and number of staff members for a particular nursing unit), reengineering involves a total overhaul of an organizational structure. It is a radical reorganization of the totality of an organization’s structure and work processes. In reengineering, fundamentally new organizational expectations and relationships are created. An example of where reengineering is required is technologic change, particularly in information services, that provides a means of customizing care. Its potential for making all information concerning a patient immediately accessible to direct care givers has the potential for a profound positive impact on healthcare decision-making.

The Transforming Care at the Bedside (TCAB) initiative is an example of redesigning the work environment from the bottom up. The initiative, funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, was started in 2003 to develop and validate an evidence-based process for transforming care in acute care facilities. Reports from TCAB facilities demonstrate the value of nurse involvement in the process as well as the value to nurses in terms of their participation (Chaboyer, Johnson, Hardy, Gehrke, & Panuwatwanich, 2010; Unruh, Agrawal, & Hassmiller, 2011).

Regardless of the level of changes made within an organization—redesign, restructuring, or reengineering—staff and patients alike feel the impact. Some of the changes result in improvements, whereas others may not; some of the impacts are expected, whereas others are not. It is critical, therefore, that nurse managers as well as direct care nurses are vigilant for both anticipated and unanticipated results of these changes. Nurses need to position themselves to participate in change discussions and evaluations. Ultimately, it is their day-to-day work with their patients that is affected by the decisions made in response to a rapidly changing environment.

Characteristics of Organizational Structures

The characteristics of different types of organizational structures provide a catalog of options to consider in designing structures that fit specific situations. Knowledge of these characteristics help leaders, managers, and nursing staff understand the expectations and structures in which they currently function.

Organizational designs are often classified by their characteristics of complexity, formalization, and centralization. Complexity concerns the division of labor in an organization, the specialization of that labor, the number of hierarchical levels, and the geographic dispersion of organizational units. Division of labor and specialization refer to the separation of processes into tasks that are performed by designated people. The horizontal dimension of an organizational chart, the graphic representation of work units and reporting relationships, relates to the division and specialization of labor functions attended by specialists. Hierarchy connotes lines of authority and responsibility. Chain of command is a term used to refer to the hierarchy and is depicted in vertical dimensions of organizational charts. Hierarchy vests authority in positions on an ascending line away from where work is performed and allows control of work. Staff members are often placed on a bottom level of the organization, and those in authority, who provide control, are placed in higher levels. Span of control refers to the number of subordinates a supervisor manages. For budgetary reasons, span of control is often a major focus for organizational restructuring. Although cost implications are present when a span of control is too narrow, when a span of control becomes too large, supervision can become less effective. The Research Perspective describes the effect of span of control.

Geographic dispersion refers to the physical location of units. Units of work may be in one building; in several buildings in one location; spread throughout a city; or in different counties, states, or countries. The more dispersed an organization is, the greater are the demands for creative designs that place decision-making related to patient care close to the patient and, consequently, far from corporate headquarters. A similar type of complexity exists in organizations that deliver care at multiple sites in the community; for example, the care delivery sites of an accountable care organization may be at great distances from the corporate office that has overall responsibility for the programs.

Formalization is the degree to which an organization has rules, stated in terms of policies that define a member’s function. The amount of formalization varies among institutions. Formalization is often inversely related to the degree of specialization and the number of professionals within the organization.

Centralization refers to the location where a decision is made. Decisions are made at the top of a centralized organization. In a decentralized organization, decisions are made at or close to the patient-care level. Highly centralized organizations often delegate responsibility (the obligation to perform the task) without the authority (the right to act, which is necessary to carry out the responsibility). For example, some hospitals have delegated both the responsibility and the authority for admission decisions to the charge nurse (decentralized), whereas others require the nurse supervisor or chief nurse executive to make such decisions (centralization). As the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) evolved guidelines to facilitate the delivery of health care, CMS identified that non-physicians, including registered nurses can write orders to admit patients so long as the practice fits with state laws and organizational policies.

Bureaucracy

Many organizational theories in use today find their basis in the works of early twenty-first century theorists Max Weber, a German sociologist who developed the basic tenets of bureaucracy (Weber, 1947), and Henri Fayol, a French industrialist who crafted 14 principles of management (Fayol, 1949). Initially, bureaucracy referred to the centralization of authority in administrative bureaus or government departments. The term has come to refer to an inflexible approach to decision making or an agency encumbered by red tape that adds little value to organizational processes. The Literature Perspective presents information about high-value organizations.

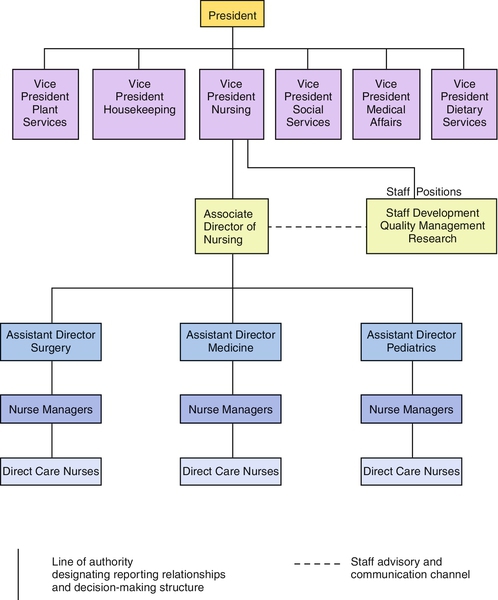

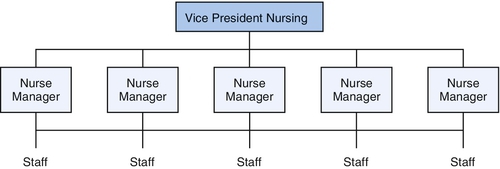

Bureaucracy is an administrative concept imbedded in how organizations are structured. The concept arose at a time of societal development when services were in short supply, workers’ and clients’ knowledge bases were limited, and technologies for sharing information were undeveloped. Characteristics of bureaucracy arose out of a need to control workers and were centered on the division of processes into discrete tasks. Weber (1947) proposed that organizations could achieve high levels of productivity and efficiency only by adherence to what he called “bureaucracy.” Weber believed that bureaucracy, based on the sociological concept of rationalization of collective activities, provided the idealized organizational structure. Bureaucratic structures are formal and have a centralized and hierarchical command structure (chain of command). Bureaucratic structures have a clear division of labor and well-articulated and commonly accepted expectations for performance. Rules, standards, and protocols ensure uniform actions and limit individualization of services and variance in workers’ performance. In bureaucratic organizations, as shown in Figure 8-1, communication and decisions flow from top to bottom. Although bureaucracy enhances consistency, by nature, it limits employee autonomy and thus the potential for innovations and client-centric service.

In developing his 14 principles of management, Fayol (1949) outlined structures and processes that guide how work is accomplished within an organization. Consistent with theories of bureaucracy, his principles of management include division of labor or specialization, clear lines of authority, appropriate levels of discipline, unity of direction, equitable treatment of staff, fostering of individual initiative, and promotion of a sense of teamwork and group pride. More than 60 years after they were described, these principles remain the basis of most organizations. Therefore, to be effective organizational leaders and followers, nurses need to be familiar with the theory and concepts of bureaucracy.

At the time that bureaucracies were developed, these characteristics promoted efficiency and production. As the knowledge base of the general population and employees grew and technologies developed, the bureaucratic structure no longer fit the evolving situation. Increasingly, employees and consumers functioning in bureaucratic situations complain of red tape, procedural delays, and general frustration.

Regardless of the form an organization takes (acute care hospital, ambulatory setting, accountable care organization, free-standing clinic, etc.), the characteristics of bureaucracy can be present in varying degrees. An organization can demonstrate bureaucratic characteristics in some areas and not in others. For example, nursing staff in intensive care units may be granted autonomy in making and carrying out direct patient care decisions, but they may not be granted a voice in determining work schedules or financial reimbursement systems for hours worked. One method to determine the extent to which bureaucratic tendencies exist in organizations is to assess the organizational characteristics of the following:

• Labor specialization (the degree to which patient care is divided into highly specialized tasks)

• Centralization (the level of the organization on which decisions regarding carrying out work and remuneration for work are made)

• Formalization (the percentage of actions required to deliver patient care that is governed by written policy and procedures)

Decision making and authority can be described in terms of line and staff functions. Line functions are those that involve direct responsibility for accomplishing the objectives of a nursing department, service, or unit. Line positions may include registered nurses, licensed practical/vocational nurses, and unlicensed assistive (or nursing) personnel who have the responsibility for carrying out all aspects of direct care. Staff functions are those that assist individuals in line positions in accomplishing the primary objectives. In this context, the term staff positions should not be confused with specific jobs that include “staff” in their names, such as staff nurse or staff physician. Staff positions include individuals, such as professional or staff development personnel, researchers, and special clinical consultants, who are responsible for supporting line positions through activities of consultation, education, role modeling, and knowledge development, with limited or no direct authority for decision-making. Line personnel have authority for decision making, whereas personnel in staff positions provide support, advice, and counsel. Organizational charts usually indicate line positions through the use of solid lines and staff positions through broken lines (reminder: in this context, the term staff (or direct care) position does not reference titles such as staff nurses). Line structures have a vertical line, designating reporting and decision-making responsibility. The vertical line connects all positions to a centralized authority (see Figure 8-1).

To make line and staff functions effective, decision-making authority is clearly spelled out in position descriptions. Effectiveness is further ensured by delineating competencies required for the responsibilities, providing methods for determining whether personnel possess these competencies, and providing means of maintaining and developing the competencies.

Types of Organizational Structures

In healthcare organizations, several common types of organizational structures exist: functional, service line, matrix, or flat. Nursing organizations often combine characteristics of these structures to form a hybrid structure. Shared governance is an organizing structure designed to meet the changing needs of professional nursing organizations.

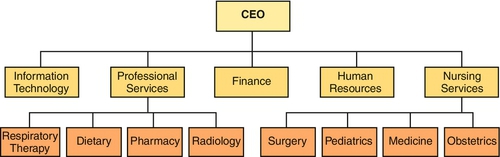

Functional Structures

Functional structures arrange departments and services according to specialty. This approach to organizational structure is common in healthcare organizations. Departments providing similar functions report to a common manager or executive (Figure 8-2). For example, a healthcare organization with a functional structure would have vice presidents for each major function: nursing, finance, human resources, and information technology.

This organizational structure tends to support professional expertise and encourage advancement. It may, however, result in discontinuity of patient care services. Delays in decision making can occur if a silo mentality develops within groups. That is, issues that require communication across functional groups typically must be raised to a senior management level before a decision can be made.

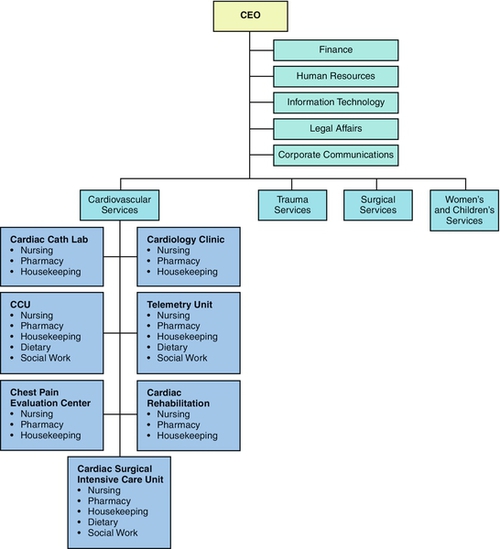

Service-Line Structures

In service-line structures (sometimes called product lines), the functions necessary to produce a specific service or product are brought together into an integrated organizational unit under the control of a single manager or executive (Figure 8-3). For example, a cardiology service line at an acute care hospital might include all professional, technical, and support personnel providing services to the cardiac patient population. The manager or executive in this service line would be responsible for the chest pain evaluation center situated within the emergency department, the coronary care unit, the cardiovascular surgery intensive care unit, the telemetry unit, the cardiac catheterization lab, and the outpatient cardiac rehabilitation center. In addition to managing the budget and the facilities for these areas, the manager typically would be responsible for coordinating services for physicians and other providers who care for these patients.

The benefits of a service-line approach to organizational structure include coordination of services, an expedited decision-making process, and clarity of purpose. The limitations of this model can include increased expense associated with duplication of services, loss of professional or technical affiliation, and lack of standardization.

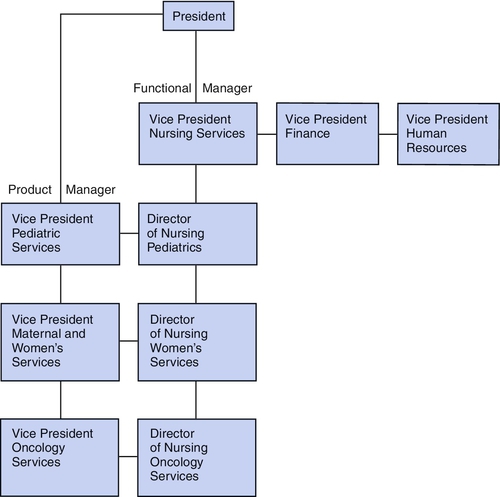

Matrix Structures

Matrix structures are complex and designed to reflect both function and service in an integrated organizational structure. In a matrix organization, the manager of a unit responsible for a service reports to both a functional manager and a service or product line manager. For example, a director of pediatric nursing could report to both a vice president for pediatric services (the service-line manager) and a vice president of nursing (the functional manager) (Figure 8-4).

Matrix structures can be effective in the current healthcare environment. The matrix design enables timely response to the forces in the external environment that demand continual programming, and it facilitates internal efficiency and effectiveness through the promotion of cooperation among disciplines.

A matrix structure combines both a bureaucratic structure and a flat structure; teams are used to carry out specific programs or projects. A matrix structure superimposes a horizontal program management over the traditional vertical hierarchy. Personnel from various functional departments are assigned to a specific program or project and become responsible to two supervisors—their functional department head and a program manager. This approach creates an interdisciplinary team.

A line manager and a project manager must function collaboratively in a matrix organization. For example, in nursing, an organization may have a chief nursing executive, a nurse manager, and direct care nurses in the line of authority to accomplish nursing care. In the matrix structure, some of the nurse’s time is allocated to project or committee work. Nursing care is delivered in a teamwork setting or within a collaborative model. The nurse is responsible to a nurse manager for nursing care and to a program or project manager when working within the matrix overlay. Well-developed collaboration and coordination skills are essential to effective functioning in a matrix structure. With the expansion of accountable care organizations, the nature of these organizations with their complex interrelationships requires nurses with high levels of knowledge and skill in interprofessional collaborative practice. (Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, 2011).

One example of the matrix structure is the patient-focused care delivery model. Another example is the program focused on specialty services such as geriatric services, women’s services, and cardiovascular services. A matrix model can be designed to cover both comprehensive patient-focused care and a specialty service. Other examples within a healthcare facility include discharge planning, quality management, and cardiopulmonary resuscitation teams.

Flat Structures

The primary organizational characteristic of a flat structure is the delegation of decision making to the professionals doing the work. The term flat signifies the removal of hierarchical layers, thereby granting authority to act and placing authority at the action level (Figure 8-5). Decisions regarding work methods, nursing care of individual patients, and conditions under which employees work are made where the work is carried out. In a flat organizational structure, decentralized decision making replaces the centralized decision making typical of functional structures. Providing staff with authority to make decisions at the place of interaction with patients is the hallmark of a flat organizational structure. Magnet™ hospitals have recognized the benefits of decentralized decision making and its impact on both nursing satisfaction and patient outcomes (Goode, Blegen, Park, Vaughn, & Spetz, 2011). An example of a flat organizational structure is that at Buurtzorg Netherlands, a home care organization where nurses manage themselves, control their schedules, and operate with few policies or procedures (Monsen & de Blok, 2013).

Flat organizational structures are less formalized than hierarchical organizations. A decrease in strict adherence to rules and policies allows individualized decisions that fit specific situations and meet the needs created by the increasing demands associated with consumerism, change, and competition. Work supported by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (www.ihi.org/IHI/), as an example, capitalizes on decisions being made at the unit level. The focus of this work is to improve patient safety and outcomes. Therefore nurses on a clinical unit can make changes in real time rather than use the traditional organizational hierarchy that includes committees and administrative channels.

Decentralized structures are not without their challenges, however. These include the potential for inconsistent decision making, loss of growth opportunities, and the need to educate managers to communicate effectively and demonstrate creativity in working within these nontraditional structures.

The degree of flattening varies from organization to organization. Those that are decentralizing often retain some bureaucratic characteristics. They may at the same time have units that are operating as matrix structures. A hybrid structure is one that has characteristics of several different types of structures.

As organizational structures change, some managers are hesitant to relinquish their traditional role in a centralized decision-making process. This reluctance, when combined with recognition of the need to move to a more facilitative role, is partially responsible for the development of hybrid structures. Managers are unsure of what needs to be controlled, how much control is needed, and which mechanisms can replace control. They fear that chaos will ensue without tight managerial control. These fears stem from loss of centralized control because authority, with its concomitant responsibilities, moves to the place of interaction. Registered nurses prepared at the higher educational level develop and use leadership techniques that empower themselves and others to take responsibility for their work and develop skills associated with effective leadership and followership. The evolutionary development of shared-governance structures in nursing departments demonstrates a type of flat structure being used to replace hierarchical control.

Shared Governance

Shared governance goes beyond participatory management through the creation of organizational structures that facilitate nursing staff having more autonomy to govern their practice. Accountability forms the foundation for designing professional governance models. To be accountable, authority to make decisions concerning all aspects of responsibilities is essential. This need for authority and accountability is particularly important for nurses who treat the wide range of human responses to wellness states and illnesses. Organizations in which professional autonomy is encouraged have demonstrated higher levels of staff satisfaction, enhanced productivity, and improved retention (Goode et al., 2011).

The historic early Magnet™ hospital study (McClure, Poulin, Sovie, & Wandelt, 1983), which identified characteristics of hospitals successful in recruiting and retaining nurses, found that the major contributing characteristic to success was a nursing department structured to provide nurses the opportunity to be accountable for their own practice. Studies of Magnet™ hospitals demonstrate that governance structures that promote nurse’s accountability will be effective in recruiting and retaining nursing staff while also meeting consumer demands and remaining competitive. Magnet™ characteristics are now accepted as affecting the quality of not only the work environment but also the patient care (Kekky, McHugh, & Aiken, 2011; McHugh, Kelly, Smith, Wu, Vanak & Aiken 2013).

Shared or self-governance structures, sometimes referred to as professional practice models, go beyond decentralizing and diminishing hierarchies. In an organization that embraces shared governance, the structure’s foundation is the professional workplace rather than the organizational hierarchy. Shared governance vests the necessary levels of authority and accountability for all aspects of the nursing practice in the nurses responsible for the delivery of care. The management and administrative level serves to coordinate and facilitate the work of the practicing nurses. Mechanisms are designed outside of the traditional hierarchy to provide for the functional areas needed to support professional practice. These functions include areas such as quality management, competency definition and evaluation, and continuing education. Changing nurses’ positions from dependent employees to accountable professionals is a prerequisite for the radical redesign of healthcare organizations that is required to create value for patients. This change requires administrators, managers, and staff to abandon traditional notions regarding the division of labor in healthcare organizations. Shared governance structures require new behaviors of all staff, not just new assignments of accountability. The areas of interpersonal relationship development, conflict resolution, and personal acceptance of responsibility for action are of particular importance. Education, experience in group work, and conflict management are essential for successful transitions. Understanding the criteria for Magnet™ facilities (American Nurses Credentialing Center, 2012), irrespective of structure, could form the basis for evaluating nursing services.

Emerging Fluid Relationships

As the continuum of care moves health services outside of institutional parameters, different skill sets, relationships, and behavioral patterns will be required. Healthcare organizations are losing their traditional boundaries. Old boundaries of hierarchy, function, and geography are disappearing. Vertical integration aligns dissimilar but related entities such as hospital, home care agency, rehabilitation center, long-term care facility, insurance provider, and medical office/clinic. New technologies, fast-changing markets, and global competition are revolutionizing relationships in health care, and the roles that people play and the tasks that they perform have become blurred and ambiguous.

In the future, more nurses will practice in settings that extend beyond the walls of a single unit or building. Reframing or changing current static organizations into vibrant learning organizations will require significant effort. To be successful in the future, nurses must participate as active members in these living-learning organizations. Nurses, whether leaders, managers, or followers, must have the ability to work with other members of the organization and with society at large to design organizational models for care delivery that meet patient/customer needs and priorities. It is essential to take a new look at the nature of the work of nursing and propose innovative models for nursing practice that consider emerging laborsaving assistive technologies and rapidly changing healthcare needs. Employee participation and learning environments go hand in hand, and work redesign needs to be regarded as a continuous process. Nurses must value their and others’ autonomy to deal successfully in these new structures.

Conclusion

Highly successful nursing organizations have grasped the importance of a mission, vision, and philosophy that are meaningful to the practice of nursing and reflect those of the organization. Organizations may be structured in various ways to provide service, and no one approach is “best” for all in all circumstances. The culture of the organization derives from these critical documents, and when embedded, they are reflected in the care delivered.

The Evidence

A theory being used to explain healthcare systems today is chaos theory. This theory suggests that differences logically exist between and among various organizations as well as between and among the units within an organization. The constantly changing forces of people and the environment affect organizational structure, its functioning, and the services provided in ways that are not often well understood or predicted. Healthcare organizations are examples of complex, unpredictable systems where individuals (healthcare professionals, patients, families, etc.) interact in ways that are nonlinear yet interconnected in substantive and important ways. Chaos theory (complexity science) is increasingly being cited in the nursing literature and is beginning to be used as a theoretical framework for nursing practice in complex adaptive systems (CASs).

An article by Hast, Digioia, Thompson, and Wolf (2013) provides an example of how understanding complexity can provide a framework for clinical intervention. In this study, the authors applied complexity science to improve the preoperative preparation experience of patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty. Using a six-step process, the authors report on the redesign of the preoperative preparation experience. They note that understanding the interrelationships within a complex adaptive system is necessary to improve outcomes.

What New Graduates Say

• Next time I apply for a job I will ask for a copy of the organization’s mission statement and philosophy of nursing. These will help me know how well I’m likely to fit in.

• Working in a Magnet™-designated facility means I have more control over the decisions that impact my patients.

• I prefer working in a hospital with a flat organizational structure. I have the chance to work with the decision makers in nursing.

Chapter Checklist

The mission, vision, and philosophy of the organization determine how nursing care is delivered in a healthcare organization. Changes occurring in the organization’s mission affect both the culture of the workplace and the philosophies regarding the work required to accomplish the mission. Actualizing new missions and philosophies requires reengineered organizational structures that place decision-making authority and responsibility where care is delivered. Decision-making responsibility requires staff to understand the organization’s mission and to participate in the development of mission and philosophy statements.

• Vision

• Philosophy

• Organizational culture

• Factors influencing organizational development

• Characteristics of organizational structures

• Bureaucracy

• Types of organizational structures

• Emerging fluid relationships

Tips for Understanding Organizational Structures

• Professional nurses in staff or followership positions need to understand the mission, vision, philosophy, and structure at the organization and unit level to maximize their contributions to patient care.

• The overall mission of the organization and the mission of the specific unit in which a professional nurse is employed or is seeking employment provide information concerning the major focus of the work to be accomplished and the manner in which it will be accomplished.

• Understanding the philosophy of the organization and/or unit where work occurs provides knowledge of the behaviors that are valued in the delivery of patient care and in interactions with persons employed by the organization.

• Formal organizational structures describe the expected channels of communication and decision making.

• Matrix organizations typically have more than one person responsible for the work, and therefore it requires understanding both the service and the function.

• For a shared-governance structure to function effectively, the professionals providing the care must put mechanisms in place to promote decision-making about patient care.