Respiratory Acidosis, Respiratory Alkalosis, and Mixed Disorders

Horacio J. Adrogué, Nicolaos E. Madias

Deviations of systemic acidity in either direction can have adverse consequences and, when severe, can be life threatening to the patient. Therefore, it is essential for the clinician to recognize and properly diagnose acid-base disorders, to understand their impact on organ function, and to be familiar with their treatment and the potential complications of treatment.1,2

Respiratory Acidosis (Primary Hypercapnia)

Definition

Respiratory acidosis is the acid-base disturbance initiated by an increase in carbon dioxide tension (PCO2) of body fluids and in whole-body CO2 stores. The secondary increment in plasma bicarbonate ion concentration (plasma [HCO3−]) observed in acute and chronic hypercapnia is an integral part of the respiratory acidosis.3 The level of arterial CO2 tension (PaCO2) is greater than 45 mm Hg in patients with simple respiratory acidosis, as measured at rest and at sea level. (To convert values from millimeters Hg to kilopascals [kP], multiply by 0.1333.) An element of respiratory acidosis may still occur with lower PaCO2 in patients residing at high altitude (e.g., 4000 m or 13,000 ft) or with metabolic acidosis, in whom a normal PaCO2 is inappropriately high for this condition.4 Another special case of respiratory acidosis is the presence of arterial eucapnia, or even hypocapnia, occurring together with severe venous hypercapnia, in patients having an acute, profound decrease in cardiac output but relative preservation of respiratory function.5,6 This disorder is known as pseudorespiratory alkalosis and is discussed under respiratory alkalosis.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

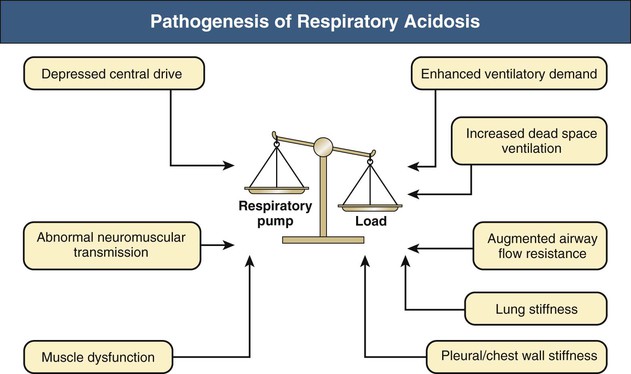

The ventilatory system is responsible for eucapnia by adjustment of alveolar minute ventilation ( ) to match the rate of CO2 production. Its main elements are the respiratory pump, which generates a pressure gradient responsible for airflow, and the loads that oppose such action.

) to match the rate of CO2 production. Its main elements are the respiratory pump, which generates a pressure gradient responsible for airflow, and the loads that oppose such action.

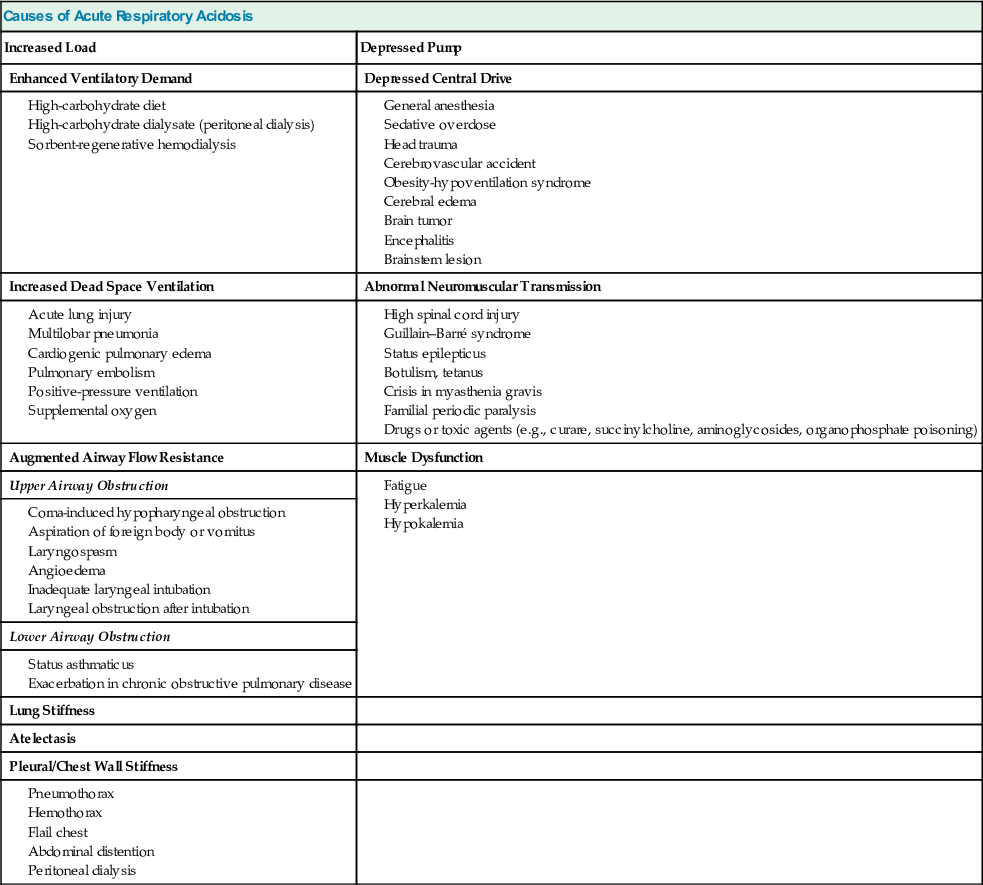

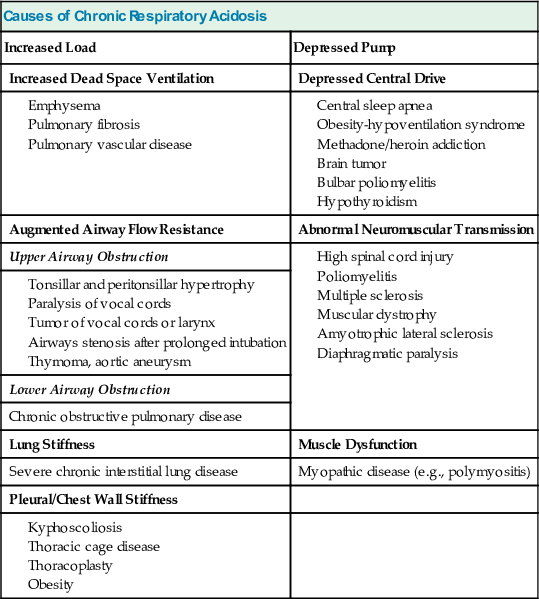

Carbon dioxide retention can occur from an imbalance between the strength of the respiratory pump and the extent of respiratory load (Fig. 14-1). When the respiratory pump is unable to balance the opposing load, respiratory acidosis develops. Respiratory acidosis may be acute or chronic (Tables 14-1 and 14-2). Life-threatening acidemia of respiratory origin can occur during severe, acute respiratory acidosis or during respiratory decompensation in patients with chronic hypercapnia.

Table 14-1

Causes of acute respiratory acidosis.

| Causes of Acute Respiratory Acidosis | |

| Increased Load | Depressed Pump |

| Enhanced Ventilatory Demand | Depressed Central Drive |

| Increased Dead Space Ventilation | Abnormal Neuromuscular Transmission |

| Augmented Airway Flow Resistance | Muscle Dysfunction |

| Upper Airway Obstruction | |

| Lower Airway Obstruction | |

| Lung Stiffness | |

| Atelectasis | |

| Pleural/Chest Wall Stiffness | |

Table 14-2

Causes of chronic respiratory acidosis.

| Causes of Chronic Respiratory Acidosis | |

| Increased Load | Depressed Pump |

| Increased Dead Space Ventilation | Depressed Central Drive |

| Augmented Airway Flow Resistance | Abnormal Neuromuscular Transmission |

| Upper Airway Obstruction | |

| Lower Airway Obstruction | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | |

| Lung Stiffness | Muscle Dysfunction |

| Severe chronic interstitial lung disease | Myopathic disease (e.g., polymyositis) |

| Pleural/Chest Wall Stiffness | |

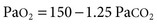

A simplified form of the alveolar gas equation at sea level and on breathing of room air (FiO2, 21%) is as follows:

where PAO2 is alveolar O2 tension (mm Hg). This equation demonstrates that patients breathing room air cannot reach PaCO2 levels much greater than 80 mm Hg (10.6 kP) because the hypoxemia that would occur at greater values is incompatible with life. Therefore, extreme hypercapnia occurs only during O2 therapy, and severe CO2 retention is often the result of uncontrolled O2 administration.

Secondary Physiologic Response

Adaptation to acute hypercapnia elicits an immediate increment in plasma [HCO3−] due to titration of non-HCO3− body buffers; such buffers generate HCO3− by combining with H+ derived from the dissociation of carbonic acid, as follows:

where B− refers to the base component and HB refers to the acid component of non-HCO3− buffers. This adaptation is completed within 5 to 10 minutes from the increase in PaCO2, and assuming a stable level of hypercapnia, no further change in acid-base equilibrium is detectable for a few hours.7 Moderate hypoxemia does not alter the adaptive response to acute respiratory acidosis. However, preexisting hypobicarbonatemia (whether it is caused by metabolic acidosis or chronic respiratory alkalosis) enhances the magnitude of the HCO3− response to acute hypercapnia; this response is diminished in hyperbicarbonatemic states, whether caused by metabolic alkalosis or chronic respiratory acidosis.8,9

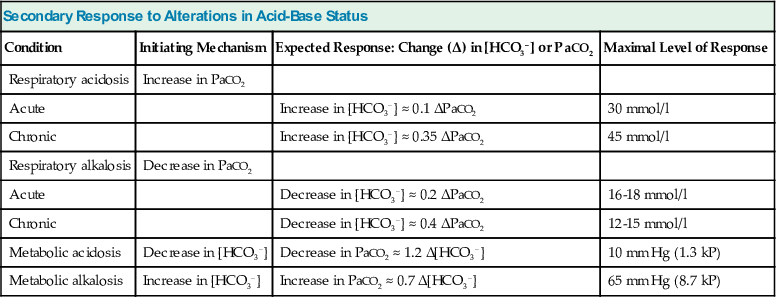

The adaptive increase in plasma [HCO3−] observed in acute hypercapnia is amplified greatly during chronic hypercapnia as a result of HCO3− generation by the kidney.10 In addition, the renal response to chronic hypercapnia includes a reduction in the rate of Cl− reabsorption, resulting in depletion of body Cl− stores. Complete adaptation to chronic hypercapnia requires 3 to 5 days.7 Table 14-3 provides quantitative aspects of the secondary physiologic responses to acute and chronic hypercapnia. More recently, a substantially steeper slope for the change in plasma [HCO3−] in chronic respiratory acidosis was reported (0.51 mmol/l for each 1 mm Hg chronic increase in PaCO2), but the small number of arterial blood gas (ABG) measurements, one for each of 18 patients, calls in question the validity of the conclusion reached.11 The renal response to chronic hypercapnia is not altered appreciably by dietary Na+ or Cl− restriction, moderate K+ depletion, alkali loading, or moderate hypoxemia. However, recovery from chronic hypercapnia is crippled by a diet deficient in Cl−; in this circumstance, despite correction of the level of PaCO2, plasma [HCO3−] remains elevated as long as the state of Cl− deprivation persists, leading to posthypercapnic metabolic alkalosis.

Table 14-3

Secondary response to alterations in acid-base status.

[HCO3−], Plasma HCO3−; PaCO2, arterial carbon dioxide tension.

| Secondary Response to Alterations in Acid-Base Status | |||

| Condition | Initiating Mechanism | Expected Response: Change (Δ) in [HCO3−] or PaCO2 | Maximal Level of Response |

| Respiratory acidosis | Increase in PaCO2 | ||

| Acute | Increase in [HCO3−] ≈ 0.1 ΔPaCO2 | 30 mmol/l | |

| Chronic | Increase in [HCO3−] ≈ 0.35 ΔPaCO2 | 45 mmol/l | |

| Respiratory alkalosis | Decrease in PaCO2 | ||

| Acute | Decrease in [HCO3−] ≈ 0.2 ΔPaCO2 | 16-18 mmol/l | |

| Chronic | Decrease in [HCO3−] ≈ 0.4 ΔPaCO2 | 12-15 mmol/l | |

| Metabolic acidosis | Decrease in [HCO3−] | Decrease in PaCO2 ≈ 1.2 Δ[HCO3−] | 10 mm Hg (1.3 kP) |

| Metabolic alkalosis | Increase in [HCO3−] | Increase in PaCO2 ≈ 0.7 Δ[HCO3−] | 65 mm Hg (8.7 kP) |

Clinical Manifestations

Because clinical hypercapnia almost always occurs in association with hypoxemia, it is often difficult to determine whether a specific manifestation is the consequence of elevated PaCO2 or reduced PaO2. Nevertheless, the clinician should bear in mind several characteristic manifestations of neurologic or cardiovascular dysfunction to diagnose the condition accurately and to treat it effectively.4,7

Neurologic Symptoms

Acute hypercapnia is often associated with marked anxiety, severe breathlessness, disorientation, confusion, incoherence, and combativeness. A narcotic-like effect can occur in patients with chronic hypercapnia, and drowsiness, decreased alertness, inattention, forgetfulness, loss of memory, irritability, confusion, and somnolence may be observed. Motor disturbances, including tremor, myoclonic jerks, and asterixis, are frequently observed with both acute and chronic hypercapnia. Sustained myoclonus and seizure activity can also develop. Signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) such as pseudotumor cerebri are occasionally evident in patients with either acute or chronic hypercapnia and appear to be related to the vasodilating effects of CO2 on cerebral blood vessels. Headache is a frequent complaint. Blurring of the optic discs and frank papilledema can be found when hypercapnia is severe. Hypercapnic coma characteristically occurs in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic respiratory insufficiency who are treated injudiciously with high-flow O2.12

Cardiovascular Symptoms

Acute hypercapnia of mild to moderate degree is usually characterized by warm and flushed skin, bounding pulse, sweating, increased cardiac output, and normal or increased blood pressure. By comparison, severe hypercapnia might be attended by decreases in both cardiac output and blood pressure. Cardiac arrhythmias occur frequently in patients with either acute or chronic hypercapnia, especially those receiving digoxin.

Renal Symptoms

Mild to moderate hypercapnia results in renal vasodilation, but acute increments in PaCO2 to levels above 70 mm Hg (9.3 kP) can induce renal vasoconstriction and hypoperfusion. Salt and water retention typically attend sustained hypercapnia, especially in the presence of cor pulmonale. In addition to the effects of heart failure on the kidney, multiple other factors might be at play, including the prevailing stimulation of the sympathetic nervous system and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis, the increased renal vascular resistance, and the elevated levels of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and cortisol.12

Diagnosis

Whenever CO2 retention is suspected, ABG values should be obtained.12 If the patient's acid-base profile reveals hypercapnia in association with acidemia, at least an element of respiratory acidosis must be present. However, hypercapnia can be associated with a normal or even an alkaline pH if certain additional acid-base disorders are also present. Information from the patient history, physical examination, and ancillary laboratory data should be used to assess whether part or all of the increase in PaCO2 reflects an adaptive response to metabolic alkalosis rather than being primary in origin.

Treatment

As previously noted, CO2 retention, whether acute or chronic, is always associated with hypoxemia in patients breathing room air. Consequently, O2 administration represents a critical element in the management of respiratory acidosis.1,13 However, supplemental O2 may lead to worsening hypercapnia, especially in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Although a depressed respiratory drive in CO2 retention seems to play a role, other factors might account for the worsening hypercapnia in response to supplemental O2 therapy. These include an increase in dead space ventilation and ventilation/perfusion ( ) mismatch caused by the loss of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and the Haldane effect (decreased hemoglobin affinity for CO2 in the presence of increased O2 saturation), which mandates an increase in ventilation to eliminate the excess CO2.7

) mismatch caused by the loss of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction and the Haldane effect (decreased hemoglobin affinity for CO2 in the presence of increased O2 saturation), which mandates an increase in ventilation to eliminate the excess CO2.7

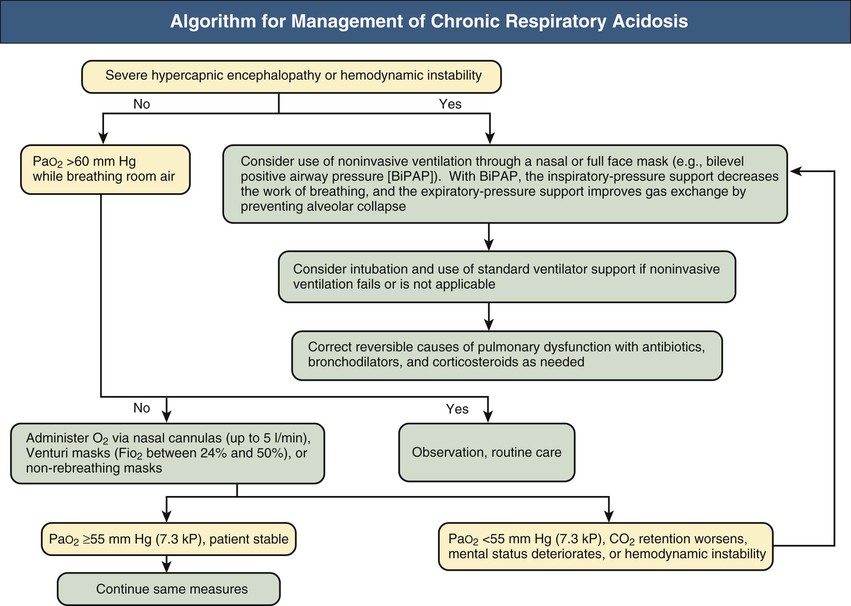

Figures 14-2 and 14-3 outline the management of acute respiratory acidosis and chronic respiratory acidosis. Whenever possible, treatment must be directed at removal or amelioration of the underlying cause. Immediate therapeutic efforts should focus on securing a patent airway and restoring adequate oxygenation by delivery of an O2-rich inspired mixture. Supplemental oxygen can be administered to the spontaneously breathing patient with nasal cannulas, Venturi masks, or non-rebreathing masks. Oxygen flow rates up to 5 l/min can be used with nasal cannulas; each increment of 1l/min increases the fraction of inspired O2 concentration (FiO2) by approximately 4%. Venturi masks, calibrated to deliver FiO2 between 24% and 50%, are most useful in patients with COPD because the PO2 can be titrated, thus minimizing the risk of CO2 retention. Oxygen saturation of hemoglobin of approximately 80% to 90% can be achieved with nonbreathing masks.

If the target Po2 is not achieved with these measures and the patient is conscious, cooperative, hemodynamically stable, and able to protect the lower airway, a method of noninvasive ventilation through a mask can be used, including bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP). With BiPAP, the inspiratory-pressure support decreases the work of breathing, and the expiratory-pressure support improves gas exchange by preventing alveolar collapse.

Endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilatory support should be initiated if adequate oxygenation cannot be secured by noninvasive measures, if progressive hypercapnia or obtundation develops, or if the patient is unable to cough and clear secretions. Minute ventilation should be raised so that the PaCO2 gradually returns to near its long-term baseline and excretion of excess HCO3− by the kidneys is accomplished (assuming that Cl− is provided). By contrast, overly rapid reduction in the PaCO2 risks the development of posthypercapnic alkalosis, with potentially serious consequences. If it develops, posthypercapnic alkalosis can be ameliorated by providing Cl−, usually as the potassium salt, and administering the HCO3−-wasting diuretic acetazolamide at doses of 250 to 500 mg once or twice daily. Vigorous treatment of pulmonary infections, bronchodilator therapy, and removal of secretions can offer considerable benefit. Naloxone will reverse the suppressive effect of narcotic agents on ventilation. Avoidance of tranquilizers and sedatives, gradual reduction of supplemental oxygen, aiming at a PaO2 of about 60 mm Hg (8 kP), and treatment of a superimposed metabolic alkalosis will optimize the ventilatory drive.

Mechanical ventilation with tidal volumes of 10 to 15 ml/kg body weight often leads to alveolar overdistention and volutrauma. Therefore, an alternative approach called permissive hypercapnia (or controlled mechanical hypoventilation) has been successfully applied to prevent barotrauma and cardiovascular collapse.4,14 In this form of treatment, lower tidal volumes of less than 6 ml/kg and lower peak inspiratory pressures are used. Further, PaCO2 is allowed to increase, but rarely exceeds 80 mm Hg, and blood pH can decrease to as low as 7.00 to 7.10, while adequate oxygenation is maintained. Because the patient usually requires neuromuscular blockade as well, accidental disconnection from the ventilator can cause sudden death. Contraindications to permissive hypercapnia include cerebrovascular disease, brain edema, increased ICP, convulsions, depressed cardiac function, arrhythmias, and severe pulmonary hypertension. Correction of acidemia attenuates the adverse hemodynamic effects of permissive hypercapnia.15 It appears prudent, although still controversial, to keep the blood pH at approximately 7.30 by the administration of intravenous alkali when controlled hypoventilation is prescribed.1,16

Respiratory Alkalosis (Primary Hypocapnia)

Definition

Respiratory alkalosis is the acid-base disturbance initiated by a reduction in CO2 tension of body fluids. The secondary decrease in plasma [HCO3−] observed in acute and chronic hypocapnia is an integral part of the respiratory alkalosis. Whole-body CO2 stores are decreased and PaCO2 is less than 35 mm Hg (4.7 kP) in patients with simple respiratory alkalosis (at rest and at sea level). An element of respiratory alkalosis may still occur with higher levels of PaCO2 in patients with metabolic alkalosis, in whom a normal PaCO2 is inappropriately low for this primary metabolic disorder.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

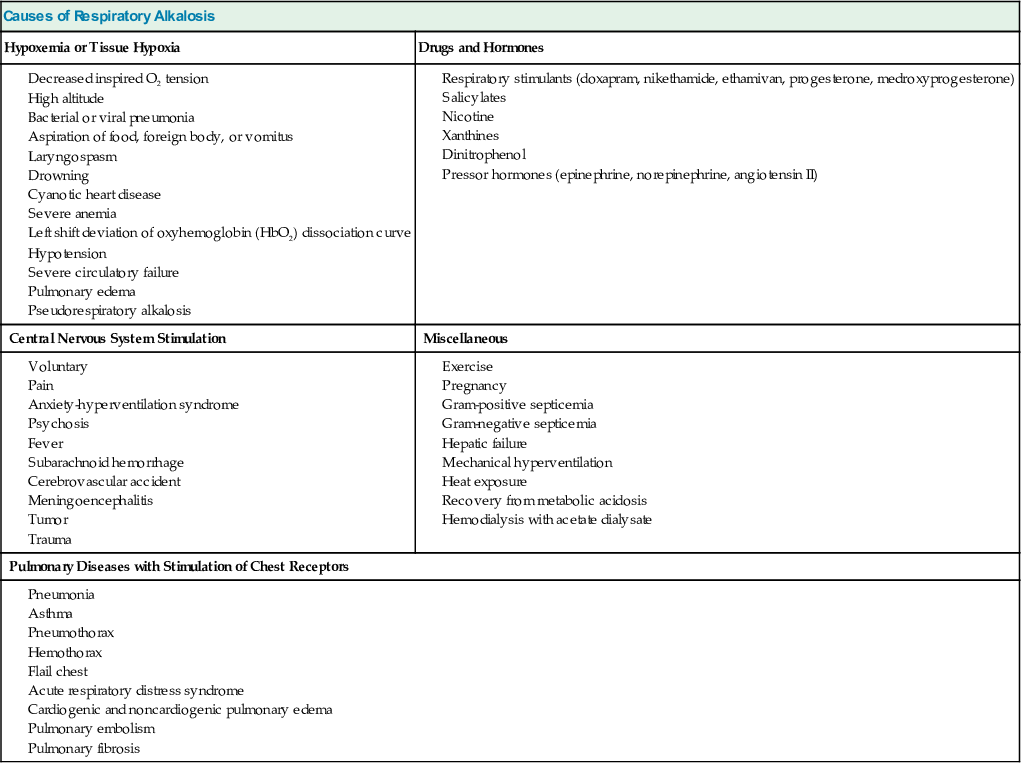

Respiratory alkalosis is the most frequent acid-base disorder encountered because it occurs in normal pregnancy and with high-altitude residence.2,17,18 It is also the most common acid-base abnormality in critically ill patients, occurring either as the simple disorder or as a component of mixed disturbances; indeed, in such patients, its presence may constitute a serious prognostic sign, especially if PaCO2 level is below 20 to 25 mm Hg (2.7 to 3.3 kP). The presence of hypocapnia signifies transient or persistent alveolar hyperventilation relative to the prevailing CO2 production, thus leading to negative CO2 balance. Primary hypocapnia might also originate from the extrapulmonary elimination of CO2 by dialysis or other extracorporeal circulation (e.g., heart-lung machine).

Table 14-4 provides the major causes of respiratory alkalosis.12 In most patients, primary hypocapnia reflects alveolar hyperventilation caused by increased ventilatory drive. This is a result of signals arising from the lung, the peripheral chemoreceptors (carotid and aortic), or the brainstem chemoreceptors, or signals originating in other brain centers.

Table 14-4

Causes of respiratory alkalosis.

| Causes of Respiratory Alkalosis | |

| Hypoxemia or Tissue Hypoxia | Drugs and Hormones |

| Central Nervous System Stimulation | Miscellaneous |

| Pulmonary Diseases with Stimulation of Chest Receptors | |

The response of the brainstem chemoreceptors to CO2 can be augmented by systemic diseases (e.g., liver disease, sepsis), pharmacologic agents, and volition. Hypoxemia is a major stimulus of alveolar ventilation, but PAO2 values below 60 mm Hg (8 kP) are required to elicit this effect consistently. Alveolar hyperventilation can be the result of maladjusted mechanical ventilators, psychogenic hyperventilation, and lesions involving the central nervous system.

In states of severe circulatory failure, arterial hypocapnia may coexist with venous and therefore tissue hypercapnia; under these conditions, the body CO2 stores have been enriched so that there is respiratory acidosis rather than respiratory alkalosis. This entity, which we have termed pseudorespiratory alkalosis, develops in patients with profound depression of cardiac function and pulmonary perfusion but relative preservation of alveolar ventilation, including patients with advanced circulatory failure and those undergoing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). The severely reduced pulmonary blood flow limits the CO2 delivered to the lungs for excretion, thereby increasing the venous PCO2. However, the increased ventilation-perfusion ratio causes a larger than normal removal of CO2 per unit of blood traversing the pulmonary circulation, thereby giving rise to arterial eucapnia or frank hypocapnia. A progressive widening of the arteriovenous difference in pH and PCO2 develops in two settings of cardiac dysfunction, circulatory failure and cardiac arrest (Fig. 14-4). In both situations, there is severe tissue O2 deprivation, and it can be completely disguised by the reasonably preserved arterial O2 values. Appropriate monitoring of acid-base composition and oxygenation in patients with advanced cardiac dysfunction requires mixed (or central) venous blood sampling in addition to the sampling of arterial blood.

Secondary Physiologic Response

Adaptation to acute hypocapnia is characterized by an immediate decrement in plasma [HCO3−] that results totally from nonrenal mechanisms and is explained principally by alkaline titration of the non-HCO3− body buffers (see second equation under Respiratory Acidosis). This adaptation is completed within 5 to 10 minutes of the onset of hypocapnia, and if there is no further change in PaCO2, no additional detectable changes in acid-base equilibrium occur for several hours.7

Adaptation to chronic hypocapnia entails an additional, larger decrease in plasma [HCO3−] as a consequence of renal adjustments that reflect a dampening of H+ secretion by the renal tubule.10 Approximately 2 to 3 days are required for completion of the adaptation to chronic hypocapnia. Quantitative aspects of the secondary physiologic responses to acute and chronic hypocapnia are shown in Table 14-3.

Clinical Manifestations

A rapid decrease in PaCO2 to half-normal values or lower is typically accompanied by numbness and paresthesias of the extremities, chest discomfort (especially in patients manifesting increased airway resistance), circumoral numbness, lightheadedness, and mental confusion. Muscle cramps, increased deep tendon reflexes, carpopedal spasm, and generalized seizures occur infrequently. Cerebral vasoconstriction and reduced cerebral blood flow have been well documented during acute hypocapnia; in severe cases, cerebral blood flow might decrease to below 50% of normal values. Hypocapnia can have deleterious effects on the brain of premature infants; in patients with traumatic brain injury, acute stroke, or general anesthesia; and after sudden exposure to very high altitude.19 Long-term neurologic sequelae can develop when immature brains are exposed to PaCO2 levels below 15 mm Hg (2 kP) for even short periods. Furthermore, abrupt correction of hypocapnia in these patients leads to cerebral vasodilation, which might cause reperfusion injury or intraventricular hemorrhage.

Brain injury caused by hypocapnia probably results from cerebral ischemia. Other factors include hypocapnia itself, alkalemia, pH-induced shift of the oxyhemoglobin (HbO2) dissociation curve, decreased levels of ionized calcium and potassium, depletion of the antioxidant glutathione by cytotoxic excitatory amino acids, increases in anaerobic metabolism, cerebral oxygen demand, neuronal dopamine, and seizure activity. If sepsis is present, brain damage worsens with the release of lipopolysaccharide, interleukin-1β, and tumor necrosis factor α.19

The cardiovascular manifestations of respiratory alkalosis differ in passive and active hyperventilation. The induction of acute hypocapnia in anesthetized patients (i.e., passive hyperventilation) results in a decrease in cardiac output, an increase in peripheral resistance, and a decrease in the systemic blood pressure. By contrast, active hyperventilation does not change or might even increase cardiac output and leaves systemic blood pressure virtually unchanged. The discrepant response of cardiac output during hyperventilation probably reflects the decrease in venous return caused by mechanical ventilation in passive hyperventilation and the reflex tachycardia consistently observed in active hyperventilation. Sustained hypocapnia induced by exposure to high altitude for several weeks results in a cardiac output within control values or higher. Although it does not lead to cardiac arrhythmias in normal individuals, acute hypocapnia appears to contribute to the generation of both atrial and ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with ischemic heart disease; such arrhythmias are frequently resistant to standard forms of therapy. Chest pain and ischemic ST-T wave changes have been observed in acutely hyperventilating patients with no evidence of fixed lesions on coronary angiography.

Diagnosis

Evaluation of the patient history, physical examination, and ancillary laboratory data are required to establish the diagnosis of respiratory alkalosis.12,17 Careful observation can detect abnormal patterns of breathing in some patients, although marked hypocapnia can occur without a clinically evident increase in respiratory effort. ABG determinations are required to confirm the presence of hyperventilation.

The diagnosis of respiratory alkalosis, especially the chronic form, is frequently missed; physicians often misinterpret the electrolyte pattern of hyperchloremic hypobicarbonatemia as indicative of normal anion gap metabolic acidosis. If the patient's acid-base profile reveals hypocapnia in association with alkalemia, at least an element of respiratory alkalosis must be present. However, hypocapnia might be associated with a normal or an acidic pH because of the concomitant presence of additional acid-base disorders. The clinician should also note that mild degrees of chronic hypocapnia leave blood pH within the high-normal range. The diagnosis of respiratory alkalosis can have important clinical implications; it often provides a clue to the presence of an unrecognized, serious disorder or signals the threat of a known underlying disease.

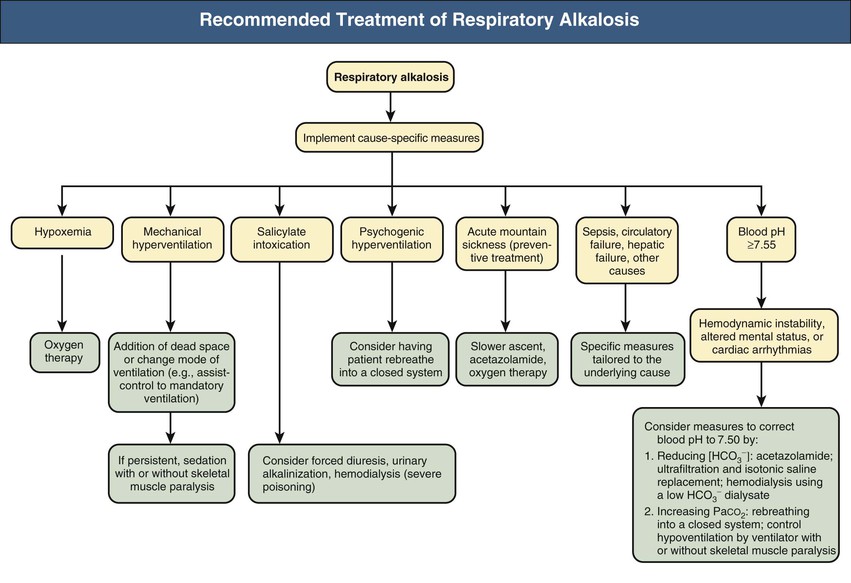

Treatment

Figure 14-5 provides a synopsis of the management of patients with respiratory alkalosis. The view that hypocapnia poses minimal risk to health under most conditions is not accurate. Substantial hypocapnia in hospitalized patients, whether spontaneous or deliberately induced, may result in transient or permanent damage in the brain as well as the respiratory and cardiovascular systems.19 Furthermore, rapid correction of severe hypocapnia leads to vasodilation of ischemic areas, resulting in reperfusion injury in the brain and lung. Consequently, severe hypocapnia in hospitalized patients must be prevented whenever possible, and if it is present, abrupt correction should be avoided. Severe alkalemia caused by acute primary hypocapnia requires corrective measures that depend on whether serious clinical manifestations are present. Such measures can be directed at reducing plasma [HCO3−], increasing PaCO2, or both. Even if baseline plasma [HCO3−]is moderately decreased, reducing it further can be particularly rewarding in these patients because this maneuver combines effectiveness with relatively little risk. For patients with the anxiety-hyperventilation syndrome, in addition to reassurance or sedation, rebreathing into a closed system (e.g., paper bag) might prove helpful by interrupting the vicious cycle that can result from the reinforcing effects of the symptoms of hypocapnia.

Respiratory alkalosis resulting from severe hypoxemia requires O2 therapy. The oral administration of 250 to 500 mg acetazolamide twice daily can be beneficial in the management of signs and symptoms of high-altitude sickness, a syndrome characterized by hypoxemia and respiratory alkalosis.17 Patients undergoing mechanical ventilation can facilitate effective correction of hypocapnia, whether from maladjusted ventilator or other factors, by resetting the device.

Mixed Acid-Base Disturbances

Definition

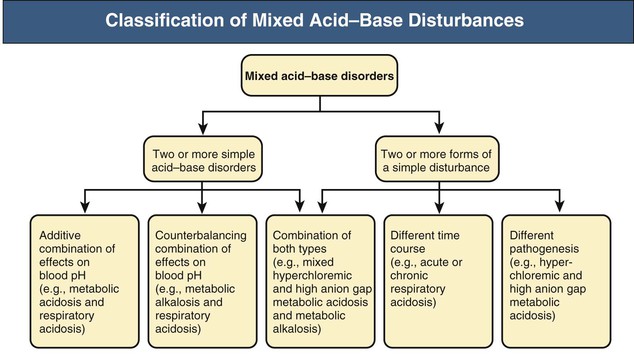

Mixed acid-base disturbances are defined as the simultaneous presence of two or more acid-base disorders. Such association might include two or more simple acid-base disorders (e.g., metabolic acidosis and respiratory alkalosis), two or more forms of a simple disturbance having different time course or pathogenesis (e.g., acute and chronic respiratory acidosis or high anion gap and hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis, respectively), or a combination of these two forms.20 The secondary or adaptive response to a simple acid-base disorder cannot be taken as one of the components of a mixed disorder.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Mixed acid-base disturbances are usually observed in hospitalized patients, especially those in critical care units.21 Characterization of these disorders and proper identification of their pathogenesis can be challenging and are a prerequisite for taking sound corrective action. Certain clinical settings are often associated with mixed acid-base disorders, including cardiorespiratory arrest, sepsis, drug intoxications, diabetes mellitus, and organ failure (especially renal, hepatic, and pulmonary failure). Patients with severe renal impairment or end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are prone to mixed acid-base disturbances of great complexity and severity.22 In these conditions, metabolic acidosis of the high anion gap type is frequently accompanied by a component of hyperchloremic acidosis, inability to mount an appropriate secondary response to chronic respiratory acidosis or alkalosis, inability to respond to a load of fixed acids (e.g., lactic acid) or a primary loss of alkali (e.g., diarrhea) with the expected increase in net acid excretion, and inability to respond to an alkali load with bicarbonaturia despite the presence of increased plasma [HCO3−]. As a result, these patients are particularly vulnerable to the development of both extreme acidemia and extreme alkalemia.

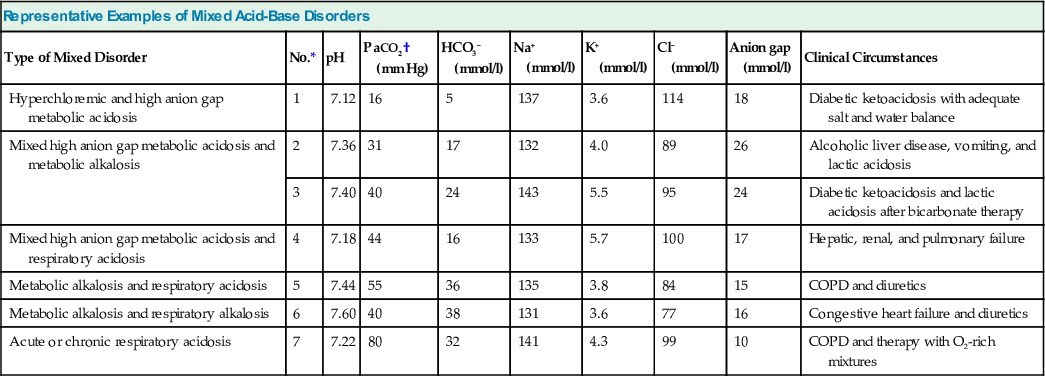

A practical classification of mixed acid-base disorders recognizes three main groups of disturbances in accordance with the preceding definition (Fig. 14-6). Representative examples are depicted in Table 14-5, and some of these mixed disorders are reviewed next.

Table 14-5

Representative examples of mixed acid-base disorders.

Anion gap is calculated as [Na+] − ([Cl−] + [HCO3−]). COPD, Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

| Representative Examples of Mixed Acid-Base Disorders | |||||||||

| Type of Mixed Disorder | No.* | pH | PaCO2† (mm Hg) | HCO3− (mmol/l) | Na+ (mmol/l) | K+ (mmol/l) | Cl− (mmol/l) | Anion gap (mmol/l) | Clinical Circumstances |

| Hyperchloremic and high anion gap metabolic acidosis | 1 | 7.12 | 16 | 5 | 137 | 3.6 | 114 | 18 | Diabetic ketoacidosis with adequate salt and water balance |

| Mixed high anion gap metabolic acidosis and metabolic alkalosis | 2 | 7.36 | 31 | 17 | 132 | 4.0 | 89 | 26 | Alcoholic liver disease, vomiting, and lactic acidosis |

| 3 | 7.40 | 40 | 24 | 143 | 5.5 | 95 | 24 | Diabetic ketoacidosis and lactic acidosis after bicarbonate therapy | |

| Mixed high anion gap metabolic acidosis and respiratory acidosis | 4 | 7.18 | 44 | 16 | 133 | 5.7 | 100 | 17 | Hepatic, renal, and pulmonary failure |

| Metabolic alkalosis and respiratory acidosis | 5 | 7.44 | 55 | 36 | 135 | 3.8 | 84 | 15 | COPD and diuretics |

| Metabolic alkalosis and respiratory alkalosis | 6 | 7.60 | 40 | 38 | 131 | 3.6 | 77 | 16 | Congestive heart failure and diuretics |

| Acute or chronic respiratory acidosis | 7 | 7.22 | 80 | 32 | 141 | 4.3 | 99 | 10 | COPD and therapy with O2-rich mixtures |

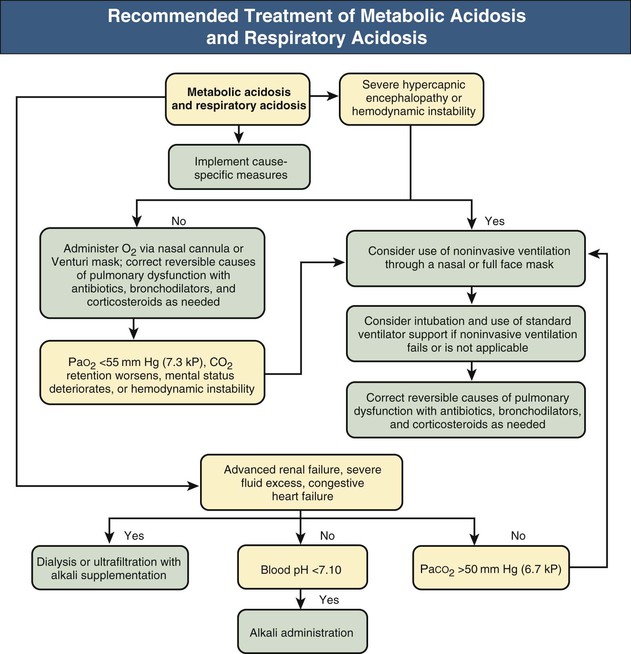

Metabolic Acidosis and Respiratory Acidosis

The expected hypocapnia secondary to metabolic acidosis is estimated by ΔPaCO2/Δ[HCO3−] = 1.2 mm Hg/mEq/l (Δ indicates change). If measured PaCO2 exceeds 5 mm Hg of the estimated value, respiratory acidosis is also present. Clinical examples of metabolic acidosis combined with respiratory acidosis include untreated cardiopulmonary arrest, circulatory failure in patients with COPD, severe renal failure associated with hypercapnic respiratory failure, various intoxications, and hypokalemic (or less frequently hyperkalemic) paralysis of respiratory muscles in patients with diarrhea or renal tubular acidosis (RTA) (Fig. 14-7 and Table 14-5, example 4).

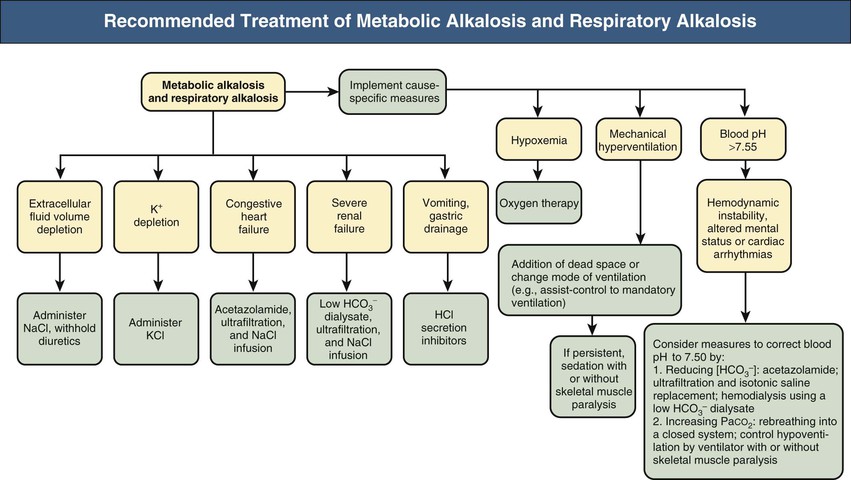

Metabolic Alkalosis and Respiratory Alkalosis

Metabolic alkalosis combined with respiratory alkalosis might be encountered in patients with primary hypocapnia associated with chronic liver disease who develop metabolic alkalosis from a variety of causes, including vomiting, nasogastric drainage, diuretics, profound hypokalemia, and alkali administration (e.g., absorption of antacids; infusion of lactated Ringer solution, alimentation solutions, citrated blood products), especially in the patient with renal impairment. Mixed metabolic/respiratory alkalosis also occurs in critically ill patients, particularly those undergoing mechanical ventilation, and in patients with respiratory alkalosis, caused by either pregnancy or heart failure, who experience metabolic alkalosis attributable to diuretics or vomiting (Fig. 14-8 and Table 14-5, example 6).

Metabolic Alkalosis and Respiratory Acidosis

Metabolic alkalosis with respiratory acidosis is one of the most frequently encountered mixed acid-base disorders. The usual clinical setting involves COPD in conjunction with diuretic therapy, but it can occur with other causes of metabolic alkalosis (e.g., vomiting, administration of corticosteroids) (Fig. 14-9 and Table 14-5, example 5). Critically ill patients with respiratory failure caused by acute respiratory distress syndrome and occasionally those with profound hypokalemia with diaphragmatic muscle weakness also might develop mixed metabolic alkalosis and respiratory acidosis.

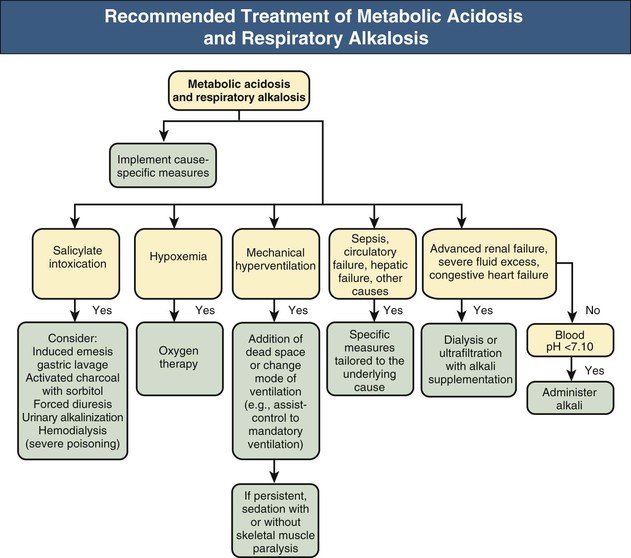

Metabolic Acidosis and Respiratory Alkalosis

As with respiratory acidosis and metabolic alkalosis, the combination of metabolic acidosis and respiratory alkalosis is characterized by normal or near-normal blood pH; its two components exert offsetting effects on systemic acidity (Fig. 14-10). This disorder is common in intensive care unit patients and is generally associated with high mortality. Causes of the primary hypocapnia include fever, hypotension, gram-negative septicemia, pulmonary edema, hypoxemia, and mechanical hyperventilation. The component of metabolic acidosis in turn might be lactic acidosis (e.g., complicating shock, hepatic failure) or renal acidosis. A considerable fraction of adults and children develop respiratory alkalosis and lactic acidosis in the course of acute severe asthma. In some patients, the lactic acidosis appears to be caused by excessive use of β2-adrenergic agonists and corticosteroids. The resulting increased ventilatory demands might worsen abnormal lung mechanics and precipitate ventilatory failure.23,24 Salicylate intoxication is another cause of mixed metabolic acidosis and respiratory alkalosis. Stimulation of the ventilatory center in the brainstem accounts for the respiratory alkalosis, whereas the accelerated production of organic acids, including pyruvic, lactic, and keto acids, and to a lesser extent the accumulation of salicylic acid itself are responsible for the metabolic acidosis.

Metabolic Acidosis and Metabolic Alkalosis

Metabolic acidosis and metabolic alkalosis are typically observed in patients with alcoholic liver disease who develop fasting ketoacidosis or lactic acidosis in conjunction with metabolic alkalosis caused by vomiting, diuretics, or other causes (Table 14-5, examples 2 and 3). Protracted vomiting or nasogastric suction superimposed on uremic acidosis, diabetic ketoacidosis, or metabolic acidosis caused by diarrhea might also generate this offsetting metabolic combination. A similar picture might develop after administration of alkali during CPR or as therapy for diabetic ketoacidosis.

Mixed Metabolic Acidosis

Mixed high anion gap metabolic acidosis in patients with diabetic or alcoholic ketoacidosis may be combined with lactic acidosis resulting from circulatory failure. Uremic patients with associated lactic acidosis or ketoacidosis provide another example of mixed high anion gap acidosis. Mixed hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis is seen in patients with RTA or those receiving carbonic anhydrase inhibitors who also have substantial fecal losses of HCO3− caused by severe diarrhea. Mixed hyperchloremic and high anion gap metabolic acidosis occurs in patients with profuse diarrhea whose circulation becomes sufficiently compromised to generate in turn a high anion gap metabolic acidosis, as a result of renal failure or lactic acidosis. Patients with diabetic ketoacidosis whose renal function is maintained at reasonable levels by adequate salt and water intake might develop an element of hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis because of preferential excretion of ketone anions and conservation of Cl− (Table 14-5, example 1).25

Mixed Metabolic Alkalosis

The coexistence of several processes with each contributing to a primary increase in plasma [HCO3−], including diuretic therapy, vomiting, mineralocorticoid excess, and severe potassium depletion, will give rise to mixed metabolic alkalosis.

Triple Disorders

The most frequent triple disorders comprise two cardinal metabolic disturbances in conjunction with either respiratory acidosis or respiratory alkalosis, such as severely ill patients with COPD and CO2 retention who simultaneously develop metabolic alkalosis (usually caused by diuretics and a Cl−-restricted diet) and metabolic acidosis (usually lactic acidosis caused by hypoxemia, hypotension, or sepsis). This type of triple disorder also might be encountered during CPR when an element of metabolic alkalosis caused by alkali administration is superimposed on preexisting respiratory acidosis and metabolic (lactic) acidosis. Patients with respiratory alkalosis caused by advanced congestive heart failure also might have diuretic-induced metabolic alkalosis and lactic acidosis from tissue hypoperfusion. Such triple acid-base disorders can also be seen in patients with chronic alcoholism who develop metabolic alkalosis from vomiting, lactic acidosis from volume depletion or ethanol intoxication, and respiratory alkalosis from hepatic encephalopathy or sepsis.

Less common triple disorders encompass two cardinal respiratory disturbances in combination with either metabolic acidosis or metabolic alkalosis. The typical presentation involves critically ill patients with chronic respiratory acidosis who experience an abrupt reduction in PaCO2 because of mechanical ventilation and superimposed metabolic acidosis (usually lactic acidosis, reflecting circulatory failure) or metabolic alkalosis (e.g., from gastric fluid loss or diuretics). With superimposed metabolic alkalosis, extreme alkalemia might ensue because of the concomitant presence of hypocapnia and hyperbicarbonatemia. Even more infrequently, this same clinical setting might lead to a quadruple acid-base disorder in which all four cardinal acid-base disturbances coexist.

Clinical Manifestations

The symptoms and signs of the underlying disease that give rise to the observed mixed acid-base disorder dominate the clinical picture, but the development of severe abnormalities in either PaCO2 (severe hypocapnia or hypercapnia) or systemic acidity (profound acidemia or alkalemia) might be responsible for the superimposition of additional clinical manifestations. On the one hand, profound hypocapnia might induce obtundation, generalized seizures, and occasionally even coma or death as a result of a critical reduction in cerebral blood flow and other mechanisms. Rarely, angina pectoris also might occur. On the other hand, severe hypercapnia might generate a profound encephalopathy with the classic features of pseudotumor cerebri, including headaches, obtundation, vomiting, and bilateral papilledema, caused by increased ICP. Extreme acidemia results in depression of the central nervous system as well as the cardiovascular system.7 Reduction in myocardial contractility and peripheral vascular resistance triggered by acidemia might result in severe hypotension. Profound alkalemia might elicit paresthesias, tetany, cardiac dysrhythmias, or generalized seizures.

Diagnosis

The basic principles underlying the diagnosis of mixed acid-base disorders are identical to those required for the identification of simple acid-base disturbances. These include assessment of the accuracy of the acid-base data by ensuring that the available values for pH, PaCO2, and plasma [HCO3−] satisfy the mathematical constraints of the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation; a careful history and performance of a complete physical examination; analysis of the plasma anion gap and other ancillary laboratory data; and knowledge of the quantitative aspects of the adaptive response to each of the four simple acid-base disturbances. Adherence to these principles cannot be overemphasized. Even experienced clinicians risk misdiagnosis of the prevailing acid-base status by bypassing this systematic approach.3

Normality of the acid-base parameters is not in itself sufficient for diagnosis of normal acid-base status; indeed, normal acid-base values might be the fortuitous result of mixed acid-base disorders (e.g., high anion gap acidosis treated with alkali infusion, diarrhea-induced metabolic acidosis in conjunction with vomiting-induced metabolic alkalosis). A given set of acid-base parameters is never diagnostic of a particular acid-base disorder, whether it is simple or mixed in nature; rather, it is consistent with a range of acid-base abnormalities. What on the surface appears to be a clear-cut simple acid-base disorder might actually reflect the interplay of a number of coexisting acid-base disturbances. The patient history and physical examination frequently provide important insights into the prevailing acid-base status as well as useful clues to the differential diagnosis.

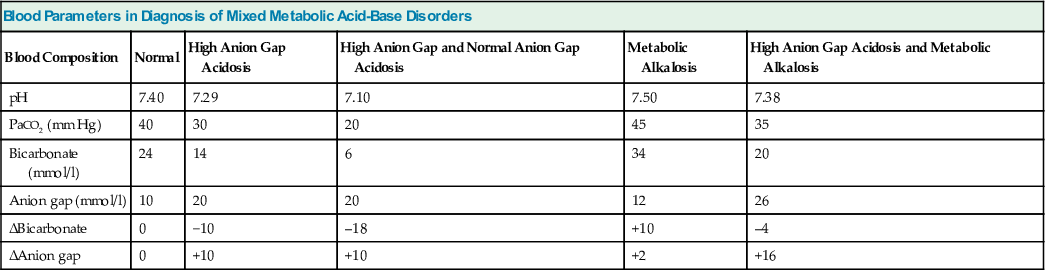

A critical component of the diagnostic process is the examination of the plasma anion gap (Table 14-6). This derived parameter provides important insights into the nature of the prevailing changes in plasma [HCO3−]. An elevated plasma anion gap might offer the first clue to the presence of disordered acid-base status despite normal acid-base parameters. With a plasma HCO3− concentration deficit (Δ[HCO3−]p), a normal or subnormal value for the plasma anion gap denotes that the entire decrease in HCO3− can be attributed to acidifying processes resulting in the loss of alkali (e.g., diarrhea, RTA) or to respiratory alkalosis. By comparison, with a high anion gap metabolic acidosis, there is usually a close reciprocal stoichiometry between the decrease in serum HCO3− and the increase in the anion gap, termed the Δ(anion gap). A reduction in serum HCO3− of 10 mmol/l is therefore associated with a Δ(anion gap) of 10 mmol/l. Addition of the value for the Δ(anion gap) to the prevailing level of serum HCO3− allows the derivation of the basal value of HCO3− existing before the development of the high anion gap metabolic acidosis. Appreciation of this reciprocal relationship between the Δ[HCO3−]p and the Δ(anion gap) is important in distinguishing between a pure high anion gap metabolic acidosis and a mixed high and normal anion gap metabolic acidosis and in detecting a mixed high anion gap metabolic acidosis and metabolic alkalosis. Additional diagnostic insights are often obtained by examination of other laboratory data, including the serum potassium, glucose, urea nitrogen, and creatinine concentrations; semiquantitative measures for ketonemia or ketonuria; screening of blood or urine for toxins; and estimation of the serum osmolar gap.

Table 14-6

Blood parameters in diagnosis of patients with mixed metabolic acid-base disorders.

| Blood Parameters in Diagnosis of Mixed Metabolic Acid-Base Disorders | |||||

| Blood Composition | Normal | High Anion Gap Acidosis | High Anion Gap and Normal Anion Gap Acidosis | Metabolic Alkalosis | High Anion Gap Acidosis and Metabolic Alkalosis |

| pH | 7.40 | 7.29 | 7.10 | 7.50 | 7.38 |

| PaCO2 (mm Hg) | 40 | 30 | 20 | 45 | 35 |

| Bicarbonate (mmol/l) | 24 | 14 | 6 | 34 | 20 |

| Anion gap (mmol/l) | 10 | 20 | 20 | 12 | 26 |

| ΔBicarbonate | 0 | −10 | –18 | +10 | –4 |

| ΔAnion gap | 0 | +10 | +10 | +2 | +16 |

Mild acid-base disorders pose particular diagnostic difficulty because of the overlap of values for the simple disturbances near the normal range. In such patients, any of several simple disorders or a variety of mixed disturbances might fully account for the acid-base data under evaluation. Again, careful correlation of all available clinical information should guide the diagnostic process.

Treatment

The management of mixed acid-base disturbances is aimed at restoration of the altered acid-base status by treatment of each simple acid-base disorder involved.1,2,20,26 Figures 14-7 to 14-10 provide recommendations for treatment of patients with some common mixed acid-base disturbances.

Given the variable response time to therapy of the individual components, it is crucial to be aware of the effect that graded correction might have on systemic acidity. The asynchronous reversal of the individual components might be used at times to therapeutic advantage; on other occasions, such a practice might prove catastrophic. For example, extreme acidemia caused by metabolic acidosis and respiratory acidosis, or extreme alkalemia caused by metabolic alkalosis and respiratory alkalosis, might be safely corrected by a rapid return of PaCO2 toward normal. By comparison, an asynchronous return of PaCO2 to normal in a patient with profound metabolic acidosis and superimposed respiratory alkalosis might prove disastrous. Similarly, extreme caution should be exercised in treating patients with respiratory acidosis and metabolic alkalosis, one of the most common mixed acid-base disorders. Although therapeutic measures intended to improve alveolar ventilation should be instituted, an abrupt decrease in PaCO2 risks development of severe alkalemia. Therefore, aggressive measures should be taken to treat metabolic alkalosis, making certain that reversal of the metabolic component does not lag behind treatment of the respiratory element. In fact, because the ventilatory drive in patients with chronic respiratory acidosis depends in part on the prevailing acidemia, reversal of a complicating element of metabolic alkalosis regularly results in improved alveolar ventilation, thus achieving a decrease in PaCO2 and an increase in PaO2.