Peritoneal Dialysis

Principles, Techniques, and Adequacy

Bengt Rippe

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is presently used by approximately 180,000 end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients worldwide, representing approximately 7% of the total dialysis population.1 In PD the peritoneal cavity, which is the largest serosal space in the body, is used as a container for 2 to 2.5 L of sterile, usually glucose-containing dialysis fluid, which is exchanged four to five times daily via a permanently indwelling catheter. The dialysis fluid is provided in plastic bags. The peritoneal membrane, via the peritoneal capillaries, acts as an endogenous dialyzing membrane. Across this membrane waste products diffuse to the dialysate, and excess body fluid is removed by osmosis induced by the glucose or another osmotic agent in the dialysis fluid, usually denoted ultrafiltration (UF). PD is usually provided 24 h/day and 7 days/wk in the form of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD). Approximately one third of the patients in most centers are on automated peritoneal dialysis (APD; sometimes also referred to as continuous cycling peritoneal dialysis [CCPD]), in which nightly exchanges are delivered via an automatic PD-cycler. The use of PD as a modality for ESRD treatment varies widely among countries, mostly because of nonmedical factors such as the reimbursement policy. One study reported that 81% of all dialysis patients in Hong Kong were treated with CAPD or APD in 2006, followed by Mexico (71%) and New Zealand (39%), whereas in the United States, PD was used by only 7.5%, and in Germany by 4.8%.

Advantages and Limitations of Peritoneal Dialysis

If patients or their care givers are competent to undertake PD, the only absolute contraindications are large diaphragmatic defects, excessive peritoneal adhesions, surgically uncorrectable abdominal hernias, or acute ischemic or infectious bowel disease. These and other relative contraindications are discussed further in Chapter 97. PD is best used for patients with some residual renal function, although anuric patients may also do very well. Most patients who start PD will eventually, after several years, transfer to other modalities of renal replacement therapy (RRT), such as hemodialysis (HD), if adequacy cannot be maintained or as a result of other complications, such as recurrent peritonitis or exit site or catheter problems. Only rarely do HD patients transfer to PD, most commonly because of failure to maintain adequate vascular access for HD.

Peritoneal dialysis offers a number of advantages over HD, at least during the first 2 or 3 years of treatment. First, PD represents a slow, continuous, physiologic mode of removal of small solutes and of excess body water, associated with relatively stable blood chemistry and body hydration status. Second, there is no need for vascular access. The absence of vascular access and the absence of the blood-membrane contact of HD make catabolic stimuli less prominent in PD than in HD. Furthermore, residual renal function is somewhat better preserved in PD patients than in HD patients. Because of its continuous nature, PD provides a standardized weekly Kt/V similar to that of thrice-weekly HD despite less efficient small-solute clearance.

Peritoneal dialysis is a home-based therapy, and most patients are trained to do the bag exchanges themselves. In general, home dialysis patients have a better quality of life than those on other types of dialysis. The number of hospital visits is reduced, and the ability to travel is increased. There is also some evidence that PD patients may be better candidates for transplantation than HD patients; several studies have shown a lower incidence and severity of delayed graft function in PD patients after transplantation.2 In children, PD (usually APD) is the preferred dialysis modality because it is noninvasive and socially acceptable, reducing hospital visits and allowing the child to attend school. Advocates of PD often recommend that RRT should ideally begin with PD according to the patient's choice and then proceed, as required when residual renal function declines, to HD or transplantation. PD should thus be regarded as part of an integrated RRT program, together with HD and transplantation.3 Factors influencing the choice of dialysis modality between PD and HD as well as global variations in the use of PD are discussed further in Chapter 90.

Principles of Peritoneal Dialysis

Three-Pore Model

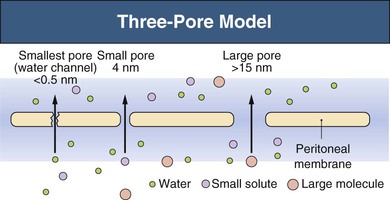

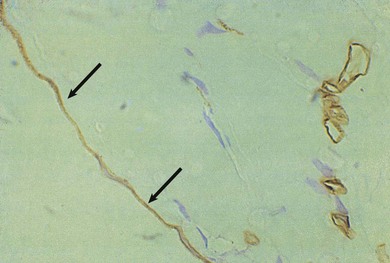

The major principles governing solute and fluid transport across the peritoneal membrane are diffusion, driven by concentration gradients, and convection (filtration or UF), driven by osmotic or hydrostatic pressure gradients. The barrier separating the plasma in the peritoneal capillaries from the fluid in the peritoneal cavity is represented by the capillary wall and the interstitium. The interstitium can be regarded as a barrier coupled in series with that of the capillary wall; the mesothelium lining the peritoneal cavity is of much less significance as a transport hindrance. For the transport of fluid (UF) and of large solutes, the capillary wall is by far the dominating transport barrier. However, for small-solute diffusion the interstitium accounts for approximately one third of the transport (diffusion) resistance. The permeability of the capillary wall can be described by a three-pore model of membrane transport (Fig. 96-1).4,5 In the capillary wall the major route for small-solute and fluid exchange between the plasma and the peritoneal cavity is the space between individual endothelial cells, the so-called interendothelial clefts. The functional radius of the permeable pathways in these clefts, denoted small pores, is 40 to 50 Å, slightly larger than the radius of albumin (36 Å). The size of these pores markedly impedes the transit of albumin and completely prevents the passage of larger molecules (e.g., immunoglobulins and α2-macroglobulin). However, larger proteins can transit via very rare large pores (radius approximately 250 Å) in capillaries and postcapillary venules. The large pores constitute only 0.01% of the total number of capillary pores, and the transport across them occurs by hydrostatic pressure–driven unidirectional filtration from the plasma to the peritoneal cavity. In addition, the capillary wall has a high permeability to osmotic water transport via aquaporin-1 (AQP-1) channels in the endothelial cell membranes (Fig. 96-2).6

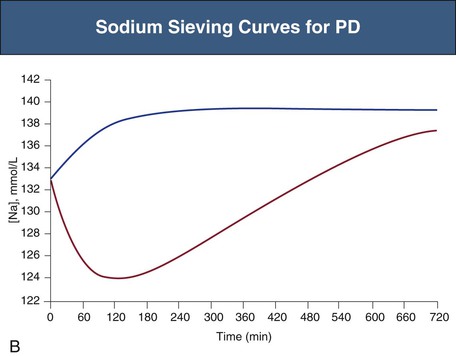

Fluid Kinetics

Under normal (non-PD) conditions most transport occurs via the small pores. Only 2% of peritoneal water transport occurs via AQP-1. In PD, fluid removal is markedly enhanced by infusion of a hyperosmolar dialysate into the peritoneal cavity. The type of osmotic agent used markedly affects the mechanism of osmosis. Glucose will induce fluid flow through both AQP-1 (approximately 45%) and small pores (approximately 55%), whereas large molecules, such as polyglucose (icodextrin) will remove fluid mainly via small pores (approximately 90%). Thus glucose osmosis will result in a rapid dilution of the peritoneal dialysate, as reflected by a fall in sodium concentration (sodium sieving) during the first 2 hours of the dialysate dwell, caused by relatively large transport via the water-only AQP-1 channels; this tends to correct later as diffusion across the small pores eventually increases the sodium concentration to that in the plasma.

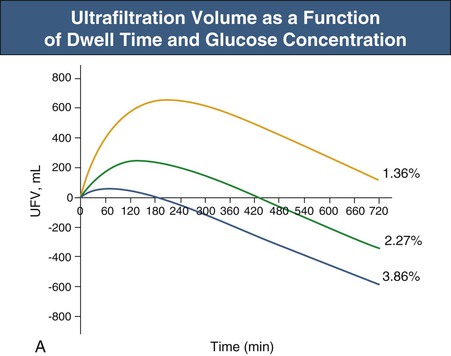

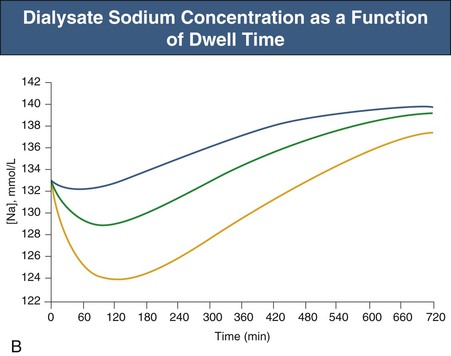

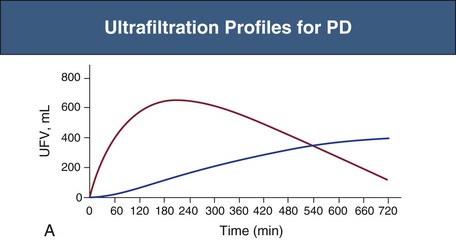

Glucose, the commonly used osmotic agent, is usually available at three concentrations: 1.36%, 2.27%, and 3.86%. Figure 96-3, A, demonstrates the intraperitoneal fluid kinetics, computer simulated using the three-pore model, over 12 hours of dwell time with these three solutions. Glucose is an intermediate-size osmolyte with a low osmotic efficiency (osmotic reflection coefficient [σ] = 0.03) across small pores, whereas glucose is 100% efficient as an osmotic agent across AQP-1 (σ = 1). For that reason, glucose will markedly (30-fold) boost the transport of fluid through AQPs and thus redistribute fluid transport away from the small pores toward AQP-1, resulting in significant sodium sieving. For example, for 3.86% glucose in the PD solution, the dialysate Na+ concentration will drop from 132 mmol/l to 123 mmol/l in 60 to 100 min, which later increases toward serum Na+ concentration (Fig. 96-3, B). On the other hand, icodextrin, with an average molecular weight of 17 kd, has a high osmotic efficiency (σ approximately 0.5) across small pores and in relative terms is rather inefficient across AQPs. Hence, during icodextrin-induced osmosis only a very minor fraction of the UF will occur through AQP-1, producing insignificant sodium sieving (see Fig. 96-7, B).

In addition to the size of the osmotic agent, the degree of sodium sieving is dependent on the presence and quantity of AQP-1, and also on the total rate of net UF (which is mainly determined by the glucose concentration), and the diffusion capacity of Na+. A high rate of small-solute transport, and thereby of sodium diffusion, in so-called fast transporters will manifest as rapid equilibration of small solutes (creatinine and glucose) in the peritoneal equilibration test (PET; see later) and will also reduce sodium sieving.

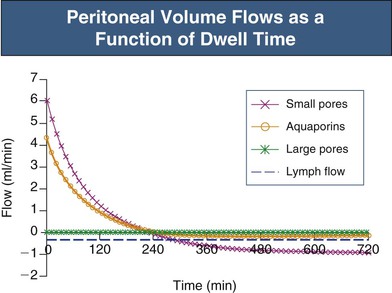

In the absence of an osmotic agent in the PD fluid, the dialysate would be reabsorbed into the plasma within a few hours, mainly driven by the difference in colloid osmotic pressure between plasma and the peritoneum. This absorption will to a major extent occur via small pores, whereas approximately 30% of the peritoneal fluid will be removed by lymphatic absorption. The partial fluid flows in the peritoneal membrane modeled across different fluid conductive pathways in the three-pore model (for 3.86% glucose) are shown in Figure 96-4. It is the presence of relatively high concentrations of glucose in the peritoneal fluid that prevents the reabsorption of fluid into the plasma during the first few hours of the dwell.

Patients who have a high rate of sodium diffusion (fast transporters) also have rapid transport of glucose out of the peritoneal cavity. Therefore the glucose gradient favoring UF dissipates more rapidly, and it is harder to achieve effective fluid removal compared with “slow transporters.” In fast transporters the maximum UF volume is reduced and UF occurs earlier. There is usually also a more rapid reabsorption of fluid in the late phase of the dwell. The issue of fluid loss from the peritoneum is, however, very controversial, because some authors claim that the peritoneal fluid loss occurring in the late phase of the PD dwell is dominated by lymphatic absorption.7

Effective Peritoneal (Vascular) Surface Area

The functional surface area of the peritoneum reflects the effective surface area of the peritoneal capillaries.8 The transport of small solutes, such as urea, creatinine and glucose, is partly limited by the degree of perfusion of these capillaries—the effective peritoneal membrane blood flow. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, some of the diffusion resistance for the smallest solutes (urea and creatinine) is located in the interstitium. The number of effectively perfused capillaries is increased by arteriolar vasodilation and reduced by vasoconstriction. These alterations often occur without large changes in the fluid permeability (hydraulic conductance [LpS]) of the peritoneum. Thus, during vasodilation or vasoconstriction there is usually a dissociation between changes in the permeability–surface area product (PS) for small solutes and in the LpS of the membrane. Vasodilation, with recruitment of capillary surface area, occurs early in the dwell when glucose is used as the osmotic agent, causing early, transient increases in PS.9

Peritonitis is also associated with marked vasodilation, again leading to increases in small-solute PS, in the absence of large changes in LpS, during the first 60 to 100 minutes of the dwell. However, in some patients with peritonitis, an increase in LpS will result in relative increased fluid transport across the small pores. Furthermore, there is usually an opening of large pores in the capillaries (and postcapillary venules), resulting in enhanced leakage of macromolecules (e.g., albumin and immunoglobulins) from plasma to peritoneum. Peritonitis may thus result in relative difficulty in removing fluid (because of rapid dissipation of intraperitoneal glucose), a reduced sodium sieving (because of the reduced UF and increased Na+ diffusion), and a markedly increased leakage of proteins to the dialysate.

The contact area between the dialysate and the peritoneal tissue varies as a result of posture and fill volume. Adult patients usually tolerate 2 to 2.5 liters of instilled volume. An intraperitoneal hydrostatic pressure (IPP) of less than 18 cm H2O (supine position) is usually tolerated.10 At higher pressures (>18 cm H2O) the patient usually feels some discomfort. At intraperitoneal volumes of less than 2 liters there is a reduction in small-solute PS, whereas PS is only moderately increased at high fill volumes. Overall, an increased fill volume implies a more efficient exchange with regard to both small-solute exchange and UF, the latter being much more pronounced for hypertonic solutions.11 For a long time it was thought that increased fill volumes would directly affect peritoneal fluid reabsorption by the hydrostatic pressure effect (increases in IPP). However, because 80% of any increase in IPP is transmitted via vein compression back to the capillaries, the actual changes in the transcapillary hydrostatic pressure gradient, which governs UF, will be rather small.12 Thus the impact of IPP on fluid absorption is moderate.13

Peritoneal Access

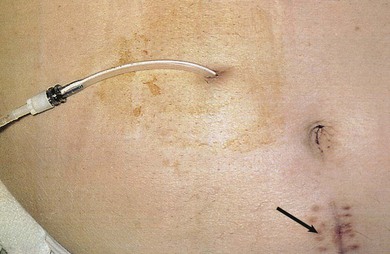

The key to successful chronic PD is a safe and permanent access to the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 96-5). Despite improvements in catheter survival over the past few years, catheter-related complications still occur, causing significant morbidity and sometimes forcing the removal of the catheter. Catheter-related problems are a cause of permanent transfer to HD in up to 20% of all patients. Most catheters are derived from that originally devised by Tenckhoff and Schechter.14 The Tenckhoff catheter is a Silastic tube with side holes along its intraperitoneal portion. There are usually one or two Dacron cuffs, allowing tissue ingrowth, which secures the catheter in place and prevents pericatheter leakage and infection. The Tenckhoff catheter is straight, having one cuff lying on the peritoneum with the catheter tip pointing in the caudal direction; the outer cuff is close to the skin exit. Several centimeters of the catheter is thus located transcutaneously. Intraperitoneal and transcutaneous catheter modifications continue to appear, indicating that no single design is perfect (Fig. 96-6). Although a number of studies report less frequent catheter drainage failures with use of the arcuate “swan neck” catheter (see Fig. 96-6) compared with straight catheters, there is no hard evidence that any of the modified catheters on the market are actually superior to the original (one- or two-cuff) Tenckhoff catheter.15

Ideally, catheter insertion should be undertaken under operating room sterile conditions by an experienced operator, either a surgeon or a nephrologist trained in interventional nephrology techniques. Presurgical assessment for the presence of herniation or any weakness of the abdominal wall is essential. If present, it may be possible to correct these at the time of catheter insertion. Before the operation, eradication of nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus with locally applied antibacterials (such as mupirocin) significantly reduces exit site infection rates. A single preoperative intravenous dose of a first- or second-generation cephalosporin is also recommended. To avoid development of vancomycin-resistant enterococcus, vancomycin should not be used as a prophylactic agent. Several placement techniques have been described and practiced: surgical mini-laparotomy and dissection, blind placement using the Tenckhoff trocar, blind placement using a guidewire (Seldinger technique), mini-trocar peritoneoscopy placement, and laparoscopy. These techniques are discussed further in Chapter 92.

Techniques of Peritoneal Dialysis

In CAPD, 2 to 2.5 liters of dialysis fluid is instilled into the peritoneal cavity four or five times daily. In 4 to 5 hours there is 95% equilibration of urea and approximately 65% equilibration of creatinine, whereas the glucose gradient has dissipated to approximately 40% of the initial value. For glucose as an osmotic agent, 4 to 5 hours is a suitable dwell time. For night dwell exchanges, longer dwell times can be accepted (8 to 10 hours), although this increases the quantity of glucose and therefore calorie absorption. Furthermore, there is room for individual exchange schedules that can be adjusted to suit individual patient convenience. Dwell times shorter than 4 to 5 hours can be performed with use of a machine (cycler). This technique can be used to maintain adequate dialysis when more frequent lower-volume exchanges are needed—for example, to minimize leakage in conjunction with catheter insertion, hernia repair, or abdominal operations. Rapid exchanges may also be required during treatment for peritonitis, or in patients with fluid overload when the patient's hydration status needs to be corrected rapidly.

Today, double-bag systems (so-called Y systems) are in general use according to the principle “flush before fill.” The double-bag system contains the unused dialysis fluid connected to an empty sterile drain bag via a Y-set tubing system. After the patient has connected the system and flushed the connection (for 2 to 3 seconds), a frangible (breakable) pin to the drain bag is opened, and the peritoneal cavity is drained over 10 to 15 minutes to fill the drain bag. Then this bag is clamped and the fresh bag opened, so as to fill the peritoneal cavity over another 10 to 15 minutes. The time for exchange (instillation and drainage), if the catheter is in good order, should not exceed a total of 30 minutes. Usually the first 1.6 to 1.8 liters will drain rapidly (at ≥200 ml/min), whereas the last 200 to 300 ml will drain much more slowly. The breakpoint between the rapid and the slow phase may vary markedly from individual to individual.

Automated peritoneal dialysis is usually performed with use of a cycler overnight (8 to 10 hours), during which large volumes (10 to 20 liters) can be exchanged. During the daytime the APD patient usually has a so-called wet day—that is, a long dwell, usually with icodextrin as the osmotic agent in the dialysis fluid. Some patients with nightly APD perform one daily exchange so that there are two long (6- to 8-hour) daily dwells. Most cyclers can be programmed to vary inflow volume, inflow time, dwell time, and drain time. Cyclers usually warm the fluid before inflow, and they also monitor outflow volume and the excess drainage (UF volume). Current APD machines have alarms for inflow failure, overheating, and poor drainage. Some cyclers interrupt drainage at the breakpoint between the fast and slow phases to make the exchange more efficient. Another way to accelerate exchanges is to allow a considerable sump volume in the peritoneal cavity by not letting all the fluid drain; subsequent inflow volumes are proportionally reduced, and after a number of cycles complete drainage occurs. This technique is called tidal peritoneal dialysis (TPD).

The exchange volume should be adjusted according to the patient's size. Adult patients weighing less than 60 kg should start with 1.5-liter bags. The average patient (60 to 80 kg) should receive 2-liter exchanges, and for patients weighing more than 80 kg, 2.5 liters should be used. If pressure monitoring systems are available, the IPP may inform the choice of exchange volume. In the supine position most patients have an IPP of 12 cm H2O.

Peritoneal Dialysis Fluids

The majority of PD fluids used today have the composition of a lactate-buffered, balanced salt solution devoid of potassium, with glucose (1.36%, 2.27%, or 3.86%) as the osmotic agent. The K+ concentration in current PD fluids is zero to aid control of potassium balance.

Lactate is used as a buffer instead of bicarbonate, because bicarbonate and Ca2+ may precipitate (to form calcium carbonate) during storage. With the advent of newer multichambered PD delivery systems, it is possible to replace lactate with bicarbonate and to make a number of other solution modifications that previously were not feasible. However, the higher cost of a number of the newer more physiologic fluid formulations should be borne in mind.

Electrolyte Concentration

In current PD fluids the concentrations of Na+, Cl−, Ca2+, and Mg2+ are selected to be close to the serum concentration. The removal of these ions across the peritoneum is therefore a result of the low diffusion gradient, more or less completely dependent on convection. For every deciliter of fluid removed in a 4-hour dwell, approximately 10 mmol of Na+16 and 0.1 mmol of Ca2+ are removed, provided that serum Na+ and Ca2+ are within the reference ranges.12

The frequent use of calcium-containing phosphate binders requires an understanding of Ca2+ kinetics for various types of dialysis fluids to avoid hypercalcemia. The calcium concentration of current PD solutions is usually 1.25 to 1.75 mmol/l. However, because Ca2+, like Na+ and Mg2+, has a UF-dominated transport, 1.25 mmol/l may be considered appropriate only for 1.36% glucose, to achieve a zero (neutral) peritoneal calcium removal. To reach the same objective for 3.86% glucose, the dialysis fluid Ca2+ would have to be increased to 2.3 mmol/l to prevent (UF-driven) Ca2+ loss during a 4-hour dwell. With use of a three-compartment system for the PD bags, it would be possible to adapt the dialysis fluid Ca2+ concentration to obtain net zero peritoneal Ca2+ transport across the peritoneum, or to reach a preset calcium removal target, for each PD fluid glucose concentration used.17 However, in currently available PD solutions, Ca2+ concentration is not variable as a function of glucose concentration; therefore 1.25 mmol/l Ca2+ is recommended when patients use calcium-containing phosphate binders. However, it should be noted that net peritoneal calcium removal with 1.25 mmol/l Ca2+ level can be achieved only by PD fluids containing 2.27% or 3.86% glucose.

The Mg2+ concentration commonly used in current PD solutions is 0.25 to 0.75 mmol/l. For 1.36% glucose, 0.25 mmol/l would be appropriate for zero Mg2+ transport during the dwell, whereas for higher dialysis fluid glucose concentrations there will be net Mg2+ losses.

Osmotic Agents

Glucose is the principal osmotic agent used for fluid removal (UF) in PD. Alternative commercially available osmotic agents are amino acids and icodextrin. Icodextrin is a polydisperse glucose polymer with an average molecular weight of 17 kd.18 However, because of the polydispersity of icodextrin, approximately 70% of the molecules have a molecular weight of 3 kd or less.11 Icodextrin is available as a 7.5% solution with essentially the same electrolyte composition as glucose-based dialysates. The osmolality of the glucose polymer solution, unlike that of 1.36% glucose (osmolality 350 mOsm/kg) dialysis fluid, is within the same range, or actually slightly lower, than that of normal serum. The presence of larger molecules in the icodextrin solution, compared with those in glucose-based solutions, improves the osmotic efficiency markedly across the small pores (σ = 0.5) and also reduces the dissipation of the osmotic gradient over time. This yields a sustained UF over 8 to 12 hours (Fig. 96-7, A). Therefore, icodextrin is preferably used for long dwell exchanges, for example, overnight, and particularly for patients who tend to absorb glucose rapidly (fast transporters, see later). Icodextrin is slowly absorbed into serum and degraded (circulating α-amylase) to oligosaccharides, such as maltose, which may give false-positive results for glucose, leading to erroneous measures of hyperglycemia and to inappropriate use of glucose-lowering agents.19

Another alternative osmotic agent that is commercially available is a 1.1% amino acid mixture having the same osmolality as 1.36% glucose.20 According to some studies, regular use of this dialysate may increase certain nutritional indices, although there is also some evidence that amino acid solutions increase acidosis and raise plasma urea. Both icodextrin-based and amino acid–based solutions may be used to reduce the glucose exposure of the peritoneal membrane and the total glucose load to the patient.

Until recently, conventional PD solutions have had a low pH and a high concentration of glucose degradation products (GDPs). GDPs are reactive carbonyl compounds that form during heat sterilization and/or storage of glucose-based solutions. GDPs are toxic to a variety of cells in vitro and also potentially toxic in vivo.21 By the use of multicompartment systems it has been possible to compose new solutions with much lower concentrations of GDPs and a neutral pH, and also to use bicarbonate or bicarbonate-lactate mixtures as buffers.22-24 Solutions using bicarbonate or bicarbonate-lactate mixtures result in significantly less infusion pain and are as effective as lactate at correcting acidosis, when used at the same total buffer ion concentration.25 In prospective, randomized studies these fluids have been associated with improvement in dialysate effluent markers of peritoneal membrane integrity, particularly cancer antigen 125 (CA-125), a measure of peritoneal mesothelial cell mass.22-24 There have also been some indications of improved residual renal function in patients with PD solutions low in GDPs,24 although this was not confirmed in recent prospective, randomized studies.26,27 One of those studies, however, the balANZ study,27 suggested that biocompatible PD solutions may delay the onset of anuria and reduce the incidence of peritonitis compared with conventional solutions.

Pyruvate is an alternative buffer to lactate (or bicarbonate) but is not yet clinically available. Finally, certain additives may help to preserve the peritoneal membrane, such as N-acetylglucosamine (NAG), hyaluronic acid (HA), citrate, and low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). LMWH, 4500 IU in every morning bag daily for 3 months, increased UF as a result of reduced glucose reabsorption during the dwell.28 This effect was, however, not found in a subsequent randomized open multicenter study of the addition of daily self-administration of LMVH (3500 IU) to the long daily icodextrin-based dwell.29 Conceivably, if LMVH actually increases UF, this action may be a result of reduction of the initial vasodilation that regularly occurs with intraperitoneal instillation of glucose-based PD solutions.28 HA seems to reduce the reabsorption of fluid that occurs in the late phase of the dwell, possibly by producing a “filter cake” at the peritoneal surface.30 None of the mentioned additives (NAG, HA, or LMWH) or buffers (pyruvate, citrate) can yet be recommended in routine clinical practice, and further trial data are awaited.

Assessments of Peritoneal Solute Transport and Ultrafiltration

Small-Solute Removal

The net removal of solutes and fluid during PD, in excess of residual renal excretion, can be measured by evaluating the drained dialysate. For this purpose the concentrations of urea and creatinine are measured in dialysate and plasma. The dialysate-plasma concentration ratios (D/P) of either of these solutes multiplied by the daily drain volume gives the 24-hour clearance. Weekly creatinine and urea clearances are obtained by multiplying these figures by 7. For comparison between patients, creatinine clearance is conventionally related to body standard surface area (1.73 m2), and urea clearance (mostly for comparison with HD) is expressed as Kt/V (where Kt is the weekly clearance and V the volume of distribution of urea). In PD, routine assessment of V is imprecise, in contrast to the situation in HD, in which V can be mathematically derived directly from urea kinetics. V should preferably be determined by direct techniques, such as from the dilution of isotopic water (total body water); in practice, however, V is usually approximated from standard tables using BW and height as anthropometric parameters together with gender.31 Criticism of the Kt/V concept in PD is based on the uncertainty of determining a correct value for V. In those who are markedly underweight or overweight the ideal body weight should be used for calculating V.32

Large-Solute Removal

For more insight into peritoneal transport, the clearance of larger solutes such as β2-microglobulin, as well as markers for transport across the large pores, such as albumin, immunoglobulins and α2-macroglobulin, can be measured. Although many centers assess the daily peritoneal removal of total protein and/or albumin, measurements of most other solutes are not made in routine clinical practice.

Ultrafiltration

Ultrafiltration can be assessed with a 24-hour collection. Even if done accurately, there is a considerable dwell-to-dwell and day-to-day variability in UF depending on drainage conditions, posture, and varying levels of residual (sump) intraperitoneal volume. Reasonably accurate estimations of daily UF volume can be obtained by averaging collections of all fluid during a period of several days. In clinical practice, the patient's own daily dialysis records should also be examined with respect to dwell-to-dwell UF volumes and the number of hypertonic bags used per day. For a 3.86% glucose dwell a UF volume less than 400 ml will indicate insufficient UF—that is, ultrafiltration failure (UFF). UF volume can also be determined by the PET as described later. In a routine 2.27% glucose PET, less than 200 mL of UF in 4 hours signals UFF. More accurate determination of intraperitoneal volume can be achieved as a function of time with use of a marker, such as iodine 125 (125I)–human serum albumin or dextran 70. This is not required in routine clinical practice but as a research tool allows more precise UF volume estimations.

Peritoneal Membrane Function

Peritoneal Equilibration Test

The PET yields approximate estimations of the rate of peritoneal transport of small solutes and of UF capacity.33 The rate of small-solute transport is dependent on the effective peritoneal surface area, which is essentially dependent on the number of effectively perfused capillaries available for exchange (and the blood flow). The volume ultrafiltrated in 4 hours is a function of the so-called osmotic conductance to glucose (OCg; the peritoneal UF coefficient times the reflection coefficient for glucose) as well as the rate of dissipation of the glucose osmotic gradient (the rate of small-solute transport). In general, when the rate of glucose disappearance is high, UF volume is low.

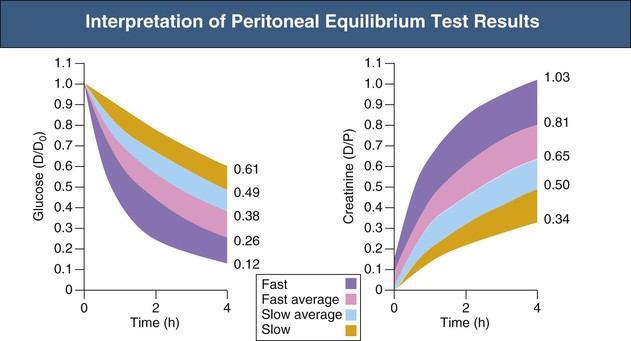

The PET procedure is summarized in Box 96-1. After an overnight dwell (8 to 12 hours) the dialysate fluid is drained, and a 2-liter 2.27% glucose bag is infused for 10 minutes with the patient in supine position (rolling from side to side every 2 minutes). After 10 minutes—that is, at completion of the infusion—200 ml is drained into the drainage bag and mixed, and a zero time dialysate sample taken. At the end of the 4-hour dwell period, dialysate is drained out and measured. The net volume is noted. Concentrations of glucose and creatinine in the outflow and plasma are measured, as well as the concentration of glucose in the zero sample. The results are expressed as the dialysate-plasma (D/P) solute concentration ratio and as the dialysate glucose at 4 hours–dialysate glucose at time zero (D/D0) concentration ratio. The higher the D/P ratio for creatinine, the faster the rate of transport for small solutes. According to D/P ratios for creatinine or D/D0 for glucose, patients can be divided into slow, slow average, fast average, or fast transporters (Fig. 96-8).

It should, however, be emphasized that D/P measurements give only an approximate estimation of small-solute transport rate. Additional information can be obtained by variations including the modified PET (instilling a 3.86% solution and draining after 4 hours),34 the mini-PET (instilling a 3.86% solution and draining after 1 hour), and the double-mini-PET (instilling sequentially a 1.36% solution and a 3.86% solution, draining each after 1 hour).

Mini–Peritoneal Equilibration Test

In the mini-PET, a 3.86% glucose solution is instilled and completely drained after 1 hour. The Na+ concentration in the drained dialysate assesses the degree of sodium sieving and hence gives a measure of AQP-mediated (“free”) water flow.35,36 The fraction of “free” water transport can be evaluated in the early phase of the dwell from the 1-hour drained volume minus the 1-hour peritoneal Na+ clearance (i.e., the drained Na+ minus the instilled Na+ divided by the serum Na+ concentration). In the first hour when Na+ diffusion is negligible, the peritoneal clearance of sodium (across small pores) will directly reflect the peritoneal small-pore fluid clearance (UF). This value is then subtracted from the total (1-hour) UF volume to yield an estimate of the free (AQP-mediated) water transport. Reductions in this parameter usually occur over time on PD, and marked reductions in free water transport are assumed to reflect peritoneal fibrosis.37,38

Double–Mini–Peritoneal Equilibration Test

The OCg can be measured with a double-mini-PET—that is, a 1-hour dwell with 1.36% glucose and also a 1-hour dwell with 3.86% glucose solution. The calculation of OCg is based on the difference in the 1-hour drained volume between the 3.86% and 1.36% glucose solutions.39 In long-term PD, increases in D/P-creatinine and reductions in D/D0-glucose are usually seen, eventually resulting in UFF. These changes are often combined with moderate reductions in OCg, the latter perhaps coupled with peritoneal fibrosis.40 Marked reductions in OCg may signal imminent development of peritoneal sclerosis.

An overview of current techniques to clinically assess peritoneal membrane function has recently been published.41

Residual Renal Function

In PD, residual renal function is of considerable importance for patient and technique survival. Residual renal function is somewhat better preserved over treatment time in PD than in HD.42 Residual renal function can be assessed by collecting all urine during a day and by assessing the urine concentrations of urea and creatinine and total urine volume. Because renal creatinine clearance, as a result of tubular secretion, yields an overestimate of the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (by 1 to 2 ml/min) when the GFR is 10 ml/min or lower, and renal urea clearance yields an underestimate of GFR (by 1 to 2 ml/min) in the same interval of (reduced) GFR, a good estimate of actual GFR can be calculated as the average of renal creatinine clearance and urea clearance. However, if the daily urine volume is less than 200 ml, residual renal function will be too small to be measured accurately.

Adequacy

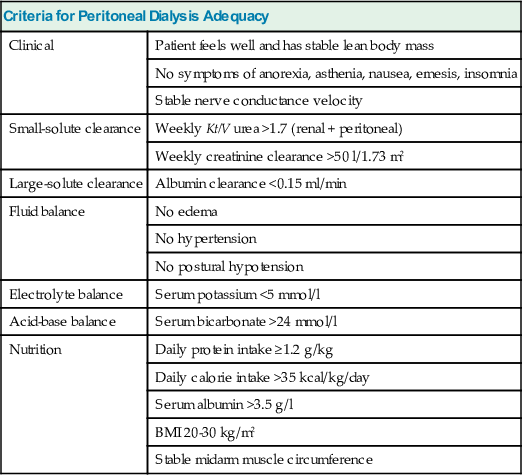

The most important measure of dialysis adequacy is the general clinical state of the patient, as manifested by a good nutritional status (maintained muscle mass) and the absence of anemia, edema, hypertension, electrolyte and acid-base disturbances, neurologic symptoms, pruritus, and insomnia. Management of anemia and bone disease in ESRD patients is discussed in Chapters 83 and 85 respectively. Some criteria for PD adequacy are given in Table 96-1.

Table 96-1

Criteria for peritoneal dialysis adequacy.

BMI, Body mass index.

| Criteria for Peritoneal Dialysis Adequacy | |

| Clinical | Patient feels well and has stable lean body mass |

| No symptoms of anorexia, asthenia, nausea, emesis, insomnia | |

| Stable nerve conductance velocity | |

| Small-solute clearance | Weekly Kt/V urea >1.7 (renal + peritoneal) |

| Weekly creatinine clearance >50 l/1.73 m2 | |

| Large-solute clearance | Albumin clearance <0.15 ml/min |

| Fluid balance | No edema |

| No hypertension | |

| No postural hypotension | |

| Electrolyte balance | Serum potassium <5 mmol/l |

| Acid-base balance | Serum bicarbonate >24 mmol/l |

| Nutrition | Daily protein intake ≥1.2 g/kg |

| Daily calorie intake >35 kcal/kg/day | |

| Serum albumin >3.5 g/l | |

| BMI 20-30 kg/m2 | |

| Stable midarm muscle circumference | |

Small-Solute Clearance

Few prospective randomized studies define adequate PD. From a clinical point of view it has been suggested that a weekly Kt/V above 1.7 and a weekly creatinine clearance above 50 l/1.73 m2 would be (minimally) adequate for patients on CAPD. In a large prospective study in the United States and Canada, the CANUSA study, the outcome for a cohort of 680 patients starting CAPD was studied with an average follow-up of 2 years.43 In this study, patients who maintained a high Kt/V or creatinine clearance over time did better than those who did not. An increase of 0.1 unit of Kt/V (peritoneal + renal) per week was associated with a 5% decrease in relative risk of death, and an increase of 5 l/1.73 m2 of creatinine clearance per week (peritoneal + renal) was associated with a 7% decrease in the relative risk of death. Further analysis of the CANUSA study findings indicated that the survival advantage of patients with higher total small-solute clearance was entirely attributed to the residual renal function. For each increase of 250 ml of urine output per day, there was a 36% decrease in the relative risk of death. In the Adequacy of Peritoneal Dialysis in Mexico (ADEMEX) study,44 a large randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT) designed to test the value of increasing peritoneal small-solute clearance in a Mexican PD cohort, there was no survival advantage of increasing the peritoneal clearance to obtain a total weekly creatinine clearance above 60 l/1.73 m2 at an average peritoneal Kt/V of 2.12 (intervention group) compared with a clearance above 50 l/1.73 m2 at an average peritoneal Kt/V of 1.56 (control group). However, although overall mortality, hospitalization, withdrawal, and technique survival were similar in the two groups, the causes of withdrawal were different. Relatively more patients in the control group withdrew because of uremia, hyperkalemia, and acidosis and died from congestive heart failure than in the intervention group.

From these studies it seems that renal and peritoneal clearance are not mutually comparable. High residual renal function is of greater survival advantage than high peritoneal solute transport capacity. The fact that the survival of PD patients is equal to or supersedes that of HD patients during the first 2 to 3 years of dialysis (see later), despite the fact that PD provides approximately 50% of the total Kt/V of HD, indicates that the benefit of PD goes beyond the clearance of small solutes. In a European multicenter study of APD, the European Automated Peritoneal Dialysis Outcomes Study (EAPOS), small-solute clearance did not correlate with survival in anuric patients.45 On the contrary, total volume removal and hydration state were important factors. Still, there is reasonably good evidence that a weekly Kt/V above 1.7 and a weekly creatinine clearance above 50 l/1.73 m2 are adequacy targets that should be reached and maintained in a majority of patients. Lower values of Kt/V and creatinine clearance have been found to be associated with more clinical problems and higher consumption of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in a large RCT.46

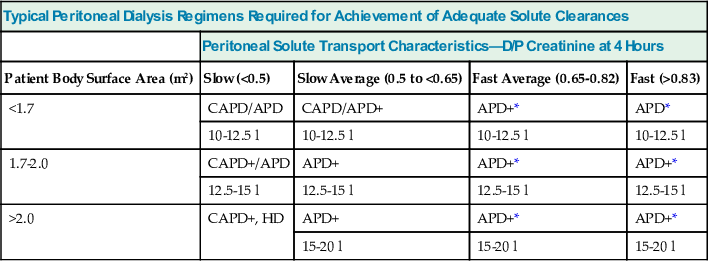

Commercially available computer programs* can predict urea and creatinine clearances and peritoneal UF performance and provide suggestions for treatment options, based on drained volumes and on plasma and dialysate creatinine and urea values. These parameters are often obtained by PET or standardized schedules for specified dwell exchanges. Some of the programs yield an estimate of peritoneal albumin clearance, which to a great extent is dependent on the filtration occurring across large pores, being increased in “inflammation.” Recommended dialysis schedules based on the categorization of the PET are given in Table 96-2.

Table 96-2

Peritoneal dialysis regimens.

Typical peritoneal dialysis regimens required to achieve adequate solute clearance according to patient size and membrane characteristics in anuric patients. The total volume of dialysate fluid required increases with body size, with use of 2.5- or even 3.0-liter exchanges. As solute transport increases, the use of automated peritoneal dialysis (APD) with shorter overnight exchanges is favored over continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD). Both CAPD and APD may have to be augmented by the use of an additional exchange (denoted by +); this is given by way of an additional afternoon exchange in CAPD patients or by use of an exchange device that delivers a single additional exchange at night. D/P, Dialysate-plasma concentration ratios; HD, hemodialysis.

| Typical Peritoneal Dialysis Regimens Required for Achievement of Adequate Solute Clearances | ||||

| Peritoneal Solute Transport Characteristics—D/P Creatinine at 4 Hours | ||||

| Patient Body Surface Area (m2) | Slow (<0.5) | Slow Average (0.5 to <0.65) | Fast Average (0.65-0.82) | Fast (>0.83) |

| <1.7 | CAPD/APD | CAPD/APD+ | APD+* | APD* |

| 10-12.5 l | 10-12.5 l | 10-12.5 l | 10-12.5 l | |

| 1.7-2.0 | CAPD+/APD | APD+ | APD+* | APD+* |

| 12.5-15 l | 12.5-15 l | 12.5-15 l | 12.5-15 l | |

| >2.0 | CAPD+, HD | APD+ | APD+* | APD+* |

| 15-20 l | 15-20 l | 15-20 l | ||

Fluid Balance

As in all types of RRT, long-term maintenance of adequate fluid and electrolyte balance is of crucial importance for the survival of patients on PD. As already mentioned, the outcome of PD is directly related to residual renal function, particularly a high urine output. Furthermore, patients with fast transport in the PET (a more rapid absorption of glucose and a more rapid loss of the osmotic gradient) have a reduced technique survival. It seems evident that after 2 or 3 years of PD, when residual renal function is low, most patients in PD are fluid overloaded.47,48 It is likely that volume overload not only aggravates hypertension but also leads to progression of left ventricular hypertrophy, often already present at the start of PD. However, during the first year of PD there is often a fall in blood pressure and a reduced need for antihypertensive agents. Unfortunately, with time on PD, blood pressure usually rises and the number of antihypertensive drugs needed usually again increases.49 Therefore it is advisable to regularly assess fluid removal in the patients over time, at least every 6 months, with a modified PET (4-hour 3.86% glucose dwell, in conjunction with a standard 2.27% 4-hour PET.

Management of Fluid Overload

As total urinary water (and sodium) excretion and peritoneal UF volume decline, it is advisable to instruct patients to restrict salt and water intake. In view of the difficulty in compliance with salt restriction, the use of PD solutions with lower sodium concentration has been advocated. Preliminary studies of low-sodium PD solutions have been very promising with regard to reducing the need for blood pressure–lowering drugs to control hypertension50; however, low-sodium solutions are not yet commercially available. Loop diuretics such as furosemide 250 to 500 mg daily can be used to maintain urine volumes but do not maintain renal clearance. If salt and water restriction and diuretics are not effective in maintaining UF, it can be enhanced by increasing the dialysis glucose concentration. Patients with alterations in peritoneal membrane function, appearing over the first few years of PD, usually have an increased small-solute transport combined with only a moderate change in peritoneal UF capacity,40 and there is an increased reabsorption of fluid in the late phase of the dwell. These patients can benefit from switching to APD and to the use of icodextrin for one of the (daily) exchanges. Randomized controlled trials using icodextrin for the long daytime dwell in APD have demonstrated an improved UF and a reduced extracellular fluid (ECF) volume.51 Patients who have been on PD for several years may have a reduced UF capacity (reduced OCg).39,40 These patients would (theoretically) benefit less from switching to icodextrin because of the reduced UF capacity.11

Nutrition

During their first year of treatment, CAPD patients typically have evidence of net anabolism; the average weight gain may exceed 5 kg without any clinical signs of fluid overload. Contributing to this weight gain is the peritoneal glucose reabsorption (on average 100 to 150 g daily), which adds 400 to 600 kcal of energy intake daily and results in metabolic syndrome in approximately 50% of prevalent PD patients.52 As residual renal function declines, the nutritional and metabolic abnormalities in CAPD become increasingly manifest, with reductions in lean body mass. The main cause of protein-energy malnutrition and wasting, apart from poor food intake, is the impaired metabolism of protein and energy in uremia. Despite glucose absorption, many patients on long-term CAPD have signs of energy malnutrition, a major component of the uremic wasting syndrome. Contributing factors are (low-grade) inflammation associated with carbonyl and oxidative stress and with accelerated atherosclerosis, the so-called malnutrition inflammation atherosclerosis (MIA) syndrome.53 It is important that CAPD patients be prescribed an adequate amount of protein (>1.2 g protein/kg/day) and energy (total energy intake >35 kcal/kg/day) and a sufficient dose of dialysis, enabling the patient to ingest this diet. It should be noted that the daily losses of protein to the dialysate are not negligible, but approximately 5 to 7 g daily, of which approximately 4 to 5 g is albumin. This actually compares with the losses occurring in nephrotic range proteinuria. The nutritional management of PD patients should include frequent assessments of their nutritional status, and if inadequate, referral for HD (or transplantation) should be considered. Nutrition in PD patients is discussed further in Chapter 87.

Outcome of Peritoneal Dialysis

Registry data have indicated a lower risk of death in patients treated with PD during the first 3 years of treatment compared with those treated with HD, although overall the mortality of patients on PD compared with HD is not significantly different.1 Survival differences seem to vary substantially according to the underlying cause of ESRD, age, and baseline comorbidity. In a study based on U.S. Medicare registry data,54 HD was associated with a higher risk of death among diabetic patients with no comorbidity and among younger patients (age 18 to 44), whereas PD was associated with a higher risk of death among older patients (age 45 to 64). In patients with mortality rates adjusted for comorbidity at start of dialysis, there were no differences between HD and PD among nondiabetic patients and among younger diabetic patients (age 18 to 44), but mortality was higher on PD for older diabetic patients with baseline comorbidity.