Anaphylaxis

Hugh A. Sampson, Julie Wang, Scott H. Sicherer

Anaphylaxis is defined as a serious allergic reaction that is rapid in onset and may cause death. Anaphylaxis in children, particularly infants, is underdiagnosed. Anaphylaxis occurs when there is a sudden release of potent biologically active mediators from mast cells and basophils, leading to cutaneous (urticaria, angioedema, flushing), respiratory (bronchospasm, laryngeal edema), cardiovascular (hypotension, dysrhythmias, myocardial ischemia), and gastrointestinal (nausea, colicky abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea) symptoms (Table 149-1).

Table 149-1

Symptoms and Signs of Anaphylaxis in Infants

| ANAPHYLAXIS SYMPTOMS THAT INFANTS CANNOT DESCRIBE | ANAPHYLAXIS SIGNS THAT MAY BE DIFFICULT TO INTERPRET/UNHELPFUL IN INFANTS, AND WHY | ANAPHYLAXIS SIGNS IN INFANTS |

| GENERAL | ||

| Feeling of warmth, weakness, anxiety, apprehension, impending doom | Nonspecific behavioral changes such as persistent crying, fussing, irritability, fright, suddenly becoming quiet | |

| SKIN/MUCUS MEMBRANES | ||

| Itching of lips, tongue, palate, uvula, ears, throat, nose, eyes, etc.; mouth-tingling or metallic taste | Flushing (may also occur with fever, hyperthermia, or crying spells) | Rapid onset of hives (potentially difficult to discern in infants with acute atopic dermatitis; scratching and excoriations will be absent in young infants); angioedema (face, tongue, oropharynx) |

| RESPIRATORY | ||

| Nasal congestion, throat tightness; chest tightness; shortness of breath | Hoarseness, dysphonia (common after a crying spell); drooling or increased secretions (common in infants) | Rapid onset of coughing, choking, stridor, wheezing, dyspnea, apnea, cyanosis |

| GASTROINTESTINAL | ||

| Dysphagia, nausea, abdominal pain/cramping | Spitting up/regurgitation (common after feeds), loose stools (normal in infants, especially if breastfed); colicky abdominal pain | Sudden, profuse vomiting |

| CARDIOVASCULAR | ||

| Feeling faint, presyncope, dizziness, confusion, blurred vision, difficulty in hearing | Hypotension (need appropriate-size blood pressure cuff; low systolic blood pressure for children is defined as <70 mm Hg from 1 mo to 1 yr, and less than (70 mm Hg + [2 × age in yr]) from 1-10 yr; tachycardia, defined as >140 beats/min from 3 mo to 2 yr, inclusive; loss of bowel and bladder control (ubiquitous in infants) | Weak pulse, arrhythmia, diaphoresis/sweating, collapse/unconsciousness |

| CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM | ||

| Headache | Drowsiness, somnolence (common in infants after feeds) | Rapid onset of unresponsiveness, lethargy, or hypotonia; seizures |

Etiology

The most common causes of anaphylaxis in children are different for hospital and community settings. Anaphylaxis occurring in the hospital results primarily from allergic reactions to medications and latex. Food allergy is the most common cause of anaphylaxis occurring outside the hospital, accounting for about half of the anaphylactic reactions reported in pediatric surveys from the United States, Italy, and South Australia (Table 149-2). Peanut allergy is an important cause of food-induced anaphylaxis, accounting for the majority of fatal and near-fatal reactions. In the hospital, latex is a particular problem for children undergoing multiple operations, such as patients with spina bifida and urologic disorders, and has prompted many hospitals to switch to latex-free products. Patients with latex allergy may also experience food-allergic reactions from homologous proteins in foods such as bananas, kiwi, avocado, chestnut, and passion fruit. Anaphylaxis to galactose-α-1,3-galactose has been reported 3-6 hr after eating meat.

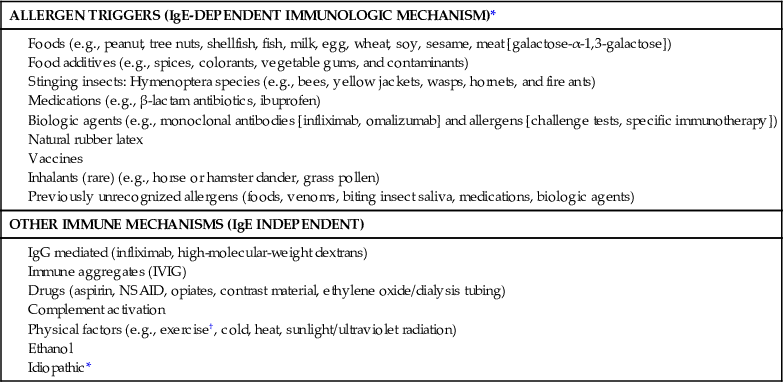

Table 149-2

Anaphylaxis Triggers in the Community*

| ALLERGEN TRIGGERS (IgE-DEPENDENT IMMUNOLOGIC MECHANISM)* |

Foods (e.g., peanut, tree nuts, shellfish, fish, milk, egg, wheat, soy, sesame, meat [galactose-α-1,3-galactose]) Food additives (e.g., spices, colorants, vegetable gums, and contaminants) Stinging insects: Hymenoptera species (e.g., bees, yellow jackets, wasps, hornets, and fire ants) Medications (e.g., β-lactam antibiotics, ibuprofen) Biologic agents (e.g., monoclonal antibodies [infliximab, omalizumab] and allergens [challenge tests, specific immunotherapy]) Inhalants (rare) (e.g., horse or hamster dander, grass pollen) Previously unrecognized allergens (foods, venoms, biting insect saliva, medications, biologic agents) |

| OTHER IMMUNE MECHANISMS (IgE INDEPENDENT) |

Epidemiology

The overall annual incidence of anaphylaxis in the United States is estimated at 50 cases/100,000 persons/yr, totaling >150,000 cases/yr, with the highest rate for the pediatric age group (0-19 yr) at 70/100,000 persons/yr. An Australian parental survey found that 0.59% of children 3-17 yr of age had experienced at least 1 anaphylactic event. Having asthma and the severity of asthma are important anaphylaxis risk factors (Table 149-3).

Table 149-3

Patient Risk Factors for Anaphylaxis

| AGE-RELATED FACTORS |

Infants: anaphylaxis can be hard to recognize, especially if the first episode; patients cannot describe symptoms Adolescents and young adults: increased risk taking behaviors such as failure to avoid known triggers and to carry an epinephrine autoinjector consistently Pregnancy: risk of iatrogenic anaphylaxis—for example, from β lactam antibiotics to prevent neonatal group B streptococcal infection, agents used perioperatively during caesarean sections, and natural rubber latex Older people: increased risk of death because of concomitant disease and drugs |

| CONCOMITANT DISEASES |

Asthma and other chronic respiratory diseases Allergic rhinitis and eczema* |

| DRUGS |

| COFACTORS THAT AMPLIFY ANAPHYLAXIS |

Pathogenesis

Principal pathologic features in fatal anaphylaxis include acute bronchial obstruction with pulmonary hyperinflation, pulmonary edema, intraalveolar hemorrhaging, visceral congestion, laryngeal edema, and urticaria and angioedema. Acute hypotension is attributed to vasomotor dilation and/or cardiac dysrhythmias.

Most cases of anaphylaxis are believed to be the result of activation of mast cells and basophils via cell-bound allergen-specific immunoglobulin (Ig) E molecules. Patients initially must be exposed to the responsible allergen to generate allergen-specific antibodies. In many cases, the child and the parent are unaware of the initial exposure, which may be from passage of food proteins in maternal breast milk or skin exposures. When the child is reexposed to the sensitizing allergen, mast cells and basophils, and possibly other cells, such as macrophages, release a variety of mediators (histamine, tryptase) and cytokines that can produce allergic symptoms in any or all target organs. Clinical anaphylaxis may also be caused by mechanisms other than IgE-mediated reactions, including direct release of mediators from mast cells by medications and physical factors (morphine, exercise, cold), disturbances of leukotriene metabolism (aspirin and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs), immune aggregates and complement activation (blood products), probable complement activation (radiocontrast dyes, dialysis membranes), and IgG-mediated reactions (high-molecular-weight dextran, chimeric or humanized monoclonal antibodies) (see Table 149-2).

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis

The onset of symptoms may vary depending on the cause of the reaction. Reactions from ingested allergens (foods, medications) are delayed in onset (minutes to 2 hr) compared with those from injected allergens (insect sting, medications) and tend to have more gastrointestinal symptoms. Initial symptoms may include any of the following constellation of symptoms: pruritus about the mouth and face; a sensation of warmth, weakness, and apprehension (sense of doom); flushing, urticaria and angioedema, oral or cutaneous pruritus, tightness in the throat, dry staccato cough and hoarseness, periocular pruritus, nasal congestion, sneezing, dyspnea, deep cough and wheezing; nausea, abdominal cramping, and vomiting, especially with ingested allergens; uterine contractions (manifesting as lower back pain); and faintness and loss of consciousness in severe cases. Some degree of obstructive laryngeal edema is typically encountered with severe reactions. Cutaneous symptoms may be absent in up to 20% of cases, and the acute onset of severe bronchospasm in a previously well asthmatic person should suggest the diagnosis of anaphylaxis. Sudden collapse in the absence of cutaneous symptoms should also raise suspicion of vasovagal collapse, myocardial infarction, aspiration, pulmonary embolism, or seizure disorder. Laryngeal edema, especially with abdominal pain, may also be a result of hereditary angioedema (see Chapter 148). Symptoms in infants may not be easy to identify (see Table 149-1).

Laboratory Findings

Laboratory studies may indicate the presence of IgE antibodies to a suspected causative agent, but this result is not definitive. Plasma histamine is elevated for a brief period but is unstable and difficult to measure in a clinical setting. Plasma tryptase is more stable and remains elevated for several hours but often is not elevated, especially in food-induced anaphylactic reactions.

Diagnosis

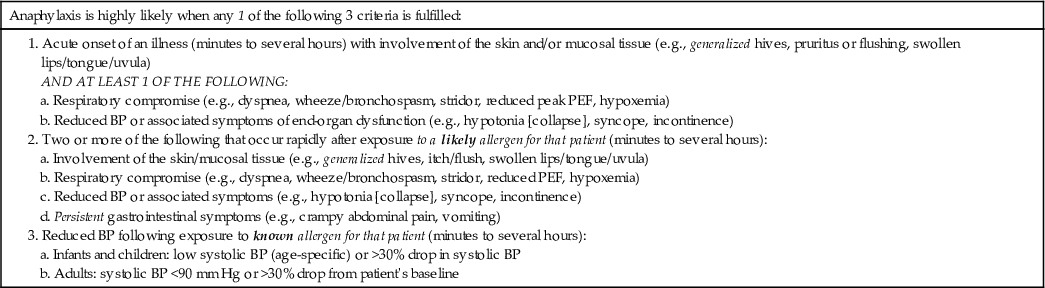

A National Institutes of Health–sponsored expert panel has recommended an approach to the diagnosis of anaphylaxis (Table 149-4). The differential diagnosis includes other forms of shock (hemorrhagic, cardiogenic, septic), vasopressor reactions including flush syndromes such as carcinoid syndrome, excess histamine syndromes (systemic mastocytosis), ingestion of monosodium glutamate, scombroidosis, and hereditary angioedema. In addition, panic attack, vocal cord dysfunction, pheochromocytoma, and red man syndrome (caused by vancomycin) should be considered.

Table 149-4

Diagnosis of Anaphylaxis

Treatment

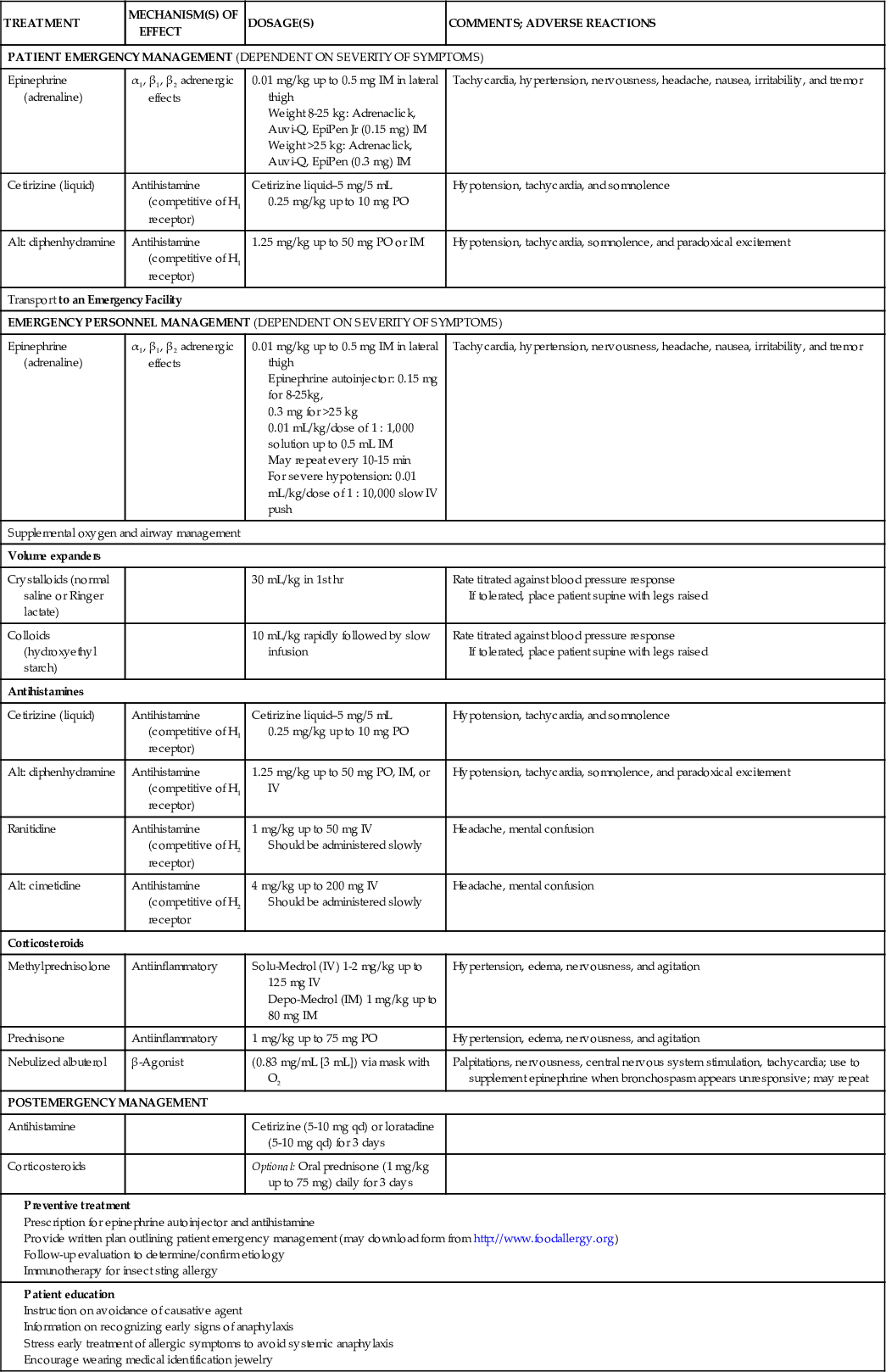

Anaphylaxis is a medical emergency requiring aggressive management with intramuscular (first line) or intravenous epinephrine, intramuscular or intravenous H1 and H2 antihistamine antagonists, oxygen, intravenous fluids, inhaled β-agonists, and corticosteroids (Table 149-5, Fig. 149-1). The initial assessment should ensure an adequate airway with effective respiration, circulation, and perfusion. Epinephrine is the most important medication, and there should be no delay in its administration. Epinephrine should be given by the intramuscular route to the lateral thigh (1 : 1000 dilution, 0.01 mg/kg; max 0.5 mg). For children ≥12 yr, many recommend the 0.5 mg intramuscular dose. The intramuscular dose can be repeated 2 or 3 times at intervals of 5-15 min if an intravenous continuous epinephrine infusion has not yet been started and symptoms persist. The 1 : 10,000 dilution of epinephrine should be used for intravenous administration. If IV access is not readily available, then epinephrine can be administered via the endotracheal or intraosseous routes. Anaphylaxis refractory to repeated doses of epinephrine has anecdotally been treated with glucagon or methylene blue. The patient should be placed in a supine position and lower extremities elevated when there is concern for hemodynamic compromise. Fluids are also important in patients with shock. Other drugs (antihistamines, glucocorticosteroids) have a secondary role in the management of anaphylaxis. Patients may experience biphasic anaphylaxis, which occurs when anaphylactic symptoms recur after apparent resolution. The mechanism of this phenomenon is unknown, but it appears to be more common when therapy is initiated late and symptoms at presentation are more severe. It does not appear to be affected by the administration of corticosteroids during the initial therapy. More than 90% of biphasic responses occur within 4 hr, so patients should be observed for at least 4 hr before being discharged from the emergency department. Referrals should be made to appropriate specialists for further evaluation and follow-up.

Table 149-5

Management of a Patient with Anaphylaxis

| TREATMENT | MECHANISM(S) OF EFFECT | DOSAGE(S) | COMMENTS; ADVERSE REACTIONS |

| PATIENT EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT (DEPENDENT ON SEVERITY OF SYMPTOMS) | |||

| Epinephrine (adrenaline) | α1, β1, β2 adrenergic effects | 0.01 mg/kg up to 0.5 mg IM in lateral thigh Weight 8-25 kg: Adrenaclick, Auvi-Q, EpiPen Jr (0.15 mg) IM Weight >25 kg: Adrenaclick, Auvi-Q, EpiPen (0.3 mg) IM | Tachycardia, hypertension, nervousness, headache, nausea, irritability, and tremor |

| Cetirizine (liquid) | Antihistamine (competitive of H1 receptor) | Cetirizine liquid–5 mg/5 mL 0.25 mg/kg up to 10 mg PO | Hypotension, tachycardia, and somnolence |

| Alt: diphenhydramine | Antihistamine (competitive of H1 receptor) | 1.25 mg/kg up to 50 mg PO or IM | Hypotension, tachycardia, somnolence, and paradoxical excitement |

| Transport to an Emergency Facility | |||

| EMERGENCY PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT (DEPENDENT ON SEVERITY OF SYMPTOMS) | |||

| Epinephrine (adrenaline) | α1, β1, β2 adrenergic effects | 0.01 mg/kg up to 0.5 mg IM in lateral thigh Epinephrine autoinjector: 0.15 mg for 8-25kg, 0.3 mg for >25 kg 0.01 mL/kg/dose of 1 : 1,000 solution up to 0.5 mL IM May repeat every 10-15 min For severe hypotension: 0.01 mL/kg/dose of 1 : 10,000 slow IV push | Tachycardia, hypertension, nervousness, headache, nausea, irritability, and tremor |

| Supplemental oxygen and airway management | |||

| Volume expanders | |||

| Crystalloids (normal saline or Ringer lactate) | 30 mL/kg in 1st hr | Rate titrated against blood pressure response If tolerated, place patient supine with legs raised | |

| Colloids (hydroxyethyl starch) | 10 mL/kg rapidly followed by slow infusion | Rate titrated against blood pressure response If tolerated, place patient supine with legs raised | |

| Antihistamines | |||

| Cetirizine (liquid) | Antihistamine (competitive of H1 receptor) | Cetirizine liquid–5 mg/5 mL 0.25 mg/kg up to 10 mg PO | Hypotension, tachycardia, and somnolence |

| Alt: diphenhydramine | Antihistamine (competitive of H1 receptor) | 1.25 mg/kg up to 50 mg PO, IM, or IV | Hypotension, tachycardia, somnolence, and paradoxical excitement |

| Ranitidine | Antihistamine (competitive of H2 receptor) | 1 mg/kg up to 50 mg IV Should be administered slowly | Headache, mental confusion |

| Alt: cimetidine | Antihistamine (competitive of H2 receptor | 4 mg/kg up to 200 mg IV Should be administered slowly | Headache, mental confusion |

| Corticosteroids | |||

| Methylprednisolone | Antiinflammatory | Solu-Medrol (IV) 1-2 mg/kg up to 125 mg IV Depo-Medrol (IM) 1 mg/kg up to 80 mg IM | Hypertension, edema, nervousness, and agitation |

| Prednisone | Antiinflammatory | 1 mg/kg up to 75 mg PO | Hypertension, edema, nervousness, and agitation |

| Nebulized albuterol | β-Agonist | (0.83 mg/mL [3 mL]) via mask with O2 | Palpitations, nervousness, central nervous system stimulation, tachycardia; use to supplement epinephrine when bronchospasm appears unresponsive; may repeat |

| POSTEMERGENCY MANAGEMENT | |||

| Antihistamine | Cetirizine (5-10 mg qd) or loratadine (5-10 mg qd) for 3 days | ||

| Corticosteroids | Optional: Oral prednisone (1 mg/kg up to 75 mg) daily for 3 days | ||

Prescription for epinephrine autoinjector and antihistamine Provide written plan outlining patient emergency management (may download form from http://www.foodallergy.org) | |||

Prevention

For patients experiencing anaphylactic reactions, the triggering agent should be avoided and education regarding early recognition of anaphylactic symptoms and administration of emergency medications should be provided. Patients with food allergies must be educated in allergen avoidance, including active reading of food ingredient labels and knowledge of potential contamination and high-risk situations. Any child with food allergy and a history of asthma, peanut, tree nut, fish or shellfish allergy, or a previous anaphylactic reaction should be given an epinephrine autoinjector (Adrenaclick, Auvi-Q, EpiPen), liquid cetirizine (or alternatively, diphenhydramine), and a written emergency plan in case of accidental ingestion. A form can be downloaded from Food Allergy Research & Education at http://www.foodallergy.org.

In cases of food-associated exercise-induced anaphylaxis, children must not exercise within 2-3 hr of ingesting the triggering food and, like children with exercise-induced anaphylaxis, should exercise with a friend, learn to recognize the early signs of anaphylaxis (sensation of warmth and facial pruritus), stop exercising, and seek help immediately if symptoms develop. Children experiencing a systemic anaphylactic reaction including respiratory symptoms to an insect sting should be evaluated and treated with immunotherapy, which is more than 90% protective. Reactions to medications can be reduced and minimized by using oral medications in preference to injected forms and avoidance of cross-reacting medications. Low osmolarity radiocontrast dyes and pretreatment can be used in patients in whom previous reactions are suspected. The use of nonlatex gloves and materials should be used in children undergoing multiple operations. Any child who is at risk for anaphylaxis should receive emergency medications (including epinephrine autoinjector), education on identification of signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis and proper administration of medications, and a written emergency plan in case of accidental exposure, and encouraged to wear medical identification jewelry.