Movement Disorders

Jonathan W. Mink

Movement disorders are characterized by abnormal or excessive involuntary movements that may result in abnormalities in posture, tone, balance, or fine motor control. Most movement disorders in children are characterized by involuntary movements. These involuntary movements can represent the sole disease manifestation, or they may be one of many signs and symptoms.

Evaluation of movement disorders begins with a comprehensive history and careful neurologic examination. It is often difficult for children and caregivers to describe abnormal movements, which makes observation of the movements by the clinician an essential component of the evaluation. If the movements are not apparent at the time of the examination, video examples from home or school can be invaluable. With the increasing availability of high quality video capability on cellular phones, obtaining a short video is feasible for most families. Resources are available to guide families in gathering useful video data.

There is no specific diagnostic test to differentiate among movement disorders. The category of movement assists in localizing the pathologic process, whereas the onset, age, and degree of abnormal motor activity and associated neurologic findings help organize the investigation.

When considering the type of movement disorder, the following questions concerning the history and examination of the movement are helpful.

◆ What is the distribution of the movements across body parts?

◆ Are the movements symmetric?

◆ What is the speed of the involuntary movements? Are they rapid and fast or slow and sustained?

◆ When do the movements occur? Are they present at rest? Are they present with maintained posture or with voluntary actions?

◆ Are the movements seen in relation to certain postures or boy positions?

◆ Do the abnormal movements occur only with specific tasks?

◆ Can the child voluntarily suppress the movements, even for a short time?

◆ Are the movements stereotyped?

◆ What is the temporal pattern of the movements? Are they continuous or intermittent? Do they occur in discrete episodes?

◆ Are the involuntary movements preceded by an urge to make the movement?

◆ Do the movements persist during sleep?

◆ Are the movements associated with impairment of motor function?

The first decision to be made is whether the movement disorder is “hyperkinetic”(characterized by excessive and involuntary movements) or “hypokinetic” (characterized by slow voluntary movements and a general paucity of movement). Hyperkinetic movement disorders are much more common than hypokinetic disorders in children. Once the category of movement disorder is recognized, etiology can be considered. Clinical history, including birth history, medication/toxin exposure, trauma, infections, family history, progression of the involuntary movements, developmental progress, and behavior should be explored as the underlying cause is established. Table 597-1 lists types and clinical characteristics of selected hyperkinetic movement disorders.

Table 597-1

Selected Types of Involuntary Movement in Childhood

| TYPE | CHARACTERISTICS |

| Stereotypies (see Chapter 24) | Involuntary, patterned, coordinated, repetitive, rhythmic movements that occur in the same fashion with each repetition |

| Tics (see Chapter 24) | Involuntary, sudden, rapid, abrupt, repetitive, nonrhythmic, simple or complex motor movements or vocalizations (phonic productions). Tics are usually preceded by an urge that is relieved by carrying out the movement |

| Tremor | Oscillating, rhythmic movements about a fixed point, axis, or plane |

| Dystonia (see Chapter 597.3) | Intermittent and sustained involuntary muscles contractions that produce abnormal postures and movements of different parts of the body, often with a twisting quality |

| Chorea (see Chapter 597.2) | Involuntary, continual, irregular movements or movement fragments with variable rate and direction that occur unpredictably and randomly |

| Ballism | Involuntary, high amplitude, flinging movements typically occurring proximally. Ballism is essentially a large amplitude chorea |

| Athetosis | Slow, writhing, continuous, involuntary movements |

| Myoclonus | Sudden, quick, involuntary muscle jerks |

Ataxias

Denia Ramirez-Montealegre, Jonathan W. Mink

Ataxia is the inability to make smooth, accurate, and coordinated movements, usually because of a dysfunction of the cerebellum, its inputs or outputs, sensory pathways in the posterior columns of the spinal cord, or a combination of these. Ataxias may be generalized or primarily affect gait or the hands and arms or trunk; they may be acute or chronic; acquired or genetic (Tables 597-2 to 597-5).

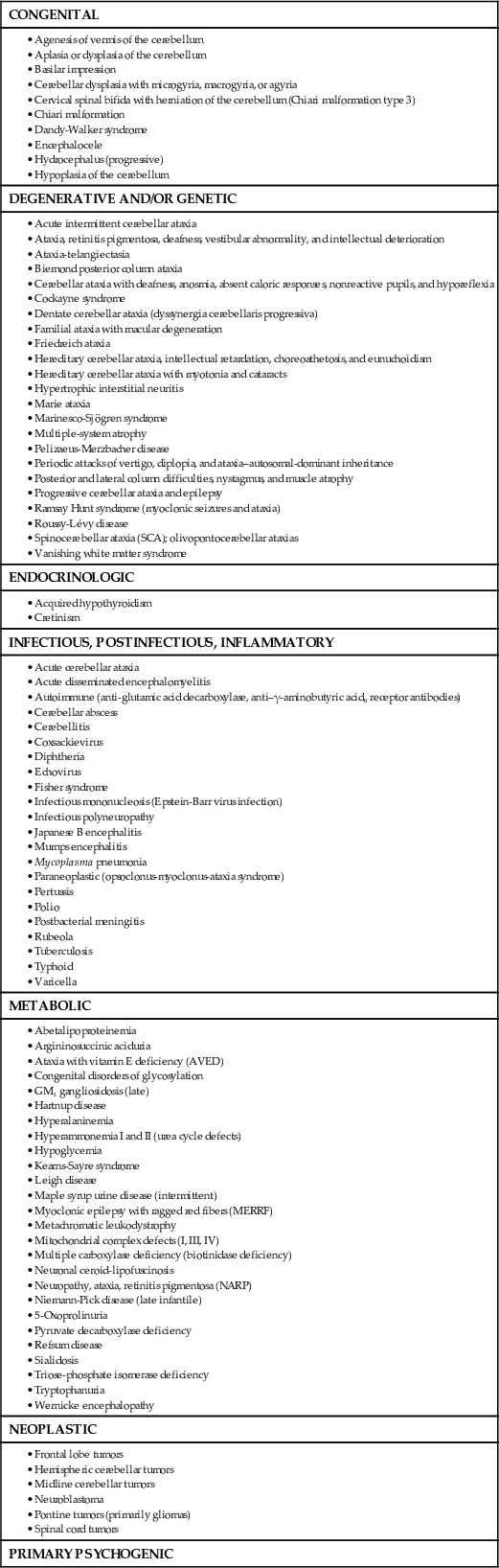

Table 597-2

Selected Causes of Ataxia in Childhood

Table 597-3

Treatable Causes of Inherited Ataxia

| DISORDER | METABOLIC ABNORMALITY | DISTINGUISHING CLINICAL FEATURES | TREATMENT |

| Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis | Demyelination | Positive MRI findings | Steroids, IVIG, rituximab |

| Ataxia with vitamin E deficiency | Mutation in α-tocopherol transfer protein | Ataxia, areflexia, retinopathy | Vitamin E |

| Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome | Abetalipoproteinemia | Acanthocytosis, retinitis pigmentosa, fat malabsorption | Vitamin E |

| Hartnup disease | Tryptophan malabsorption | Pellagra rash, intermittent ataxia | Niacin |

| Familial episodic ataxia type 1 and type 2 | Mutations in potassium channel (KCNA1) and α1A voltage-gated calcium channel, respectively | Episodic attacks, worse with pregnancy or birth control pills | Acetazolamide |

| Multiple carboxylase deficiency | Biotinidase deficiency | Alopecia, recurrent infections, variable organic aciduria | Biotin |

| Mitochondrial complex defects | Complexes I, III, IV | Encephalomyelopathy | Possibly riboflavin, CoQ10, dichloroacetate |

| Opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome | Paraneoplastic or spontaneous autoimmune | Underlying neuroblastoma or autoantibodies | Steroids, IVIG, rituximab |

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase deficiency | Block in E-M and Krebs cycle interface | Lactic acidosis, ataxia | Ketogenic diet, possibly dichloroacetate |

| Refsum disease | Phytanic acid, α-hydroxylase | Retinitis pigmentosa, cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic neuropathy, ichthyosis | Dietary restriction of phytanic acid |

| Urea cycle defects | Urea cycle enzymes | Hyperammonemia | Protein restriction, arginine, benzoate, α-ketoacids |

Table 597-4

Autosomal-Recessive Cerebellar Ataxias

| ATAXIA | CHROMOSOME | GENE | GENE PRODUCT | MECHANISM | AGE OF ONSET (yr) |

| Friedreich ataxia | 9q13 | X25 | Frataxin | GAA repeat | 2-51 |

| Friedreich ataxia 2 | 9p23–p11 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 5-20 |

| AVED | 8q13 | TTP1 | TTPA | Missense mutation, deletion, insertion | 2-52 |

| Ataxia-telangiectasia | 11q22.3 | ATM | ATM | Missense and deletion mutations | Infancy |

| ATLD | 11q21 | hMRE11 | MRE11A | Missense and deletion mutations | 9-48 mo |

| Ataxia-ocular apraxia 1 | 9p13.3 | APTX | Aprataxin | Frameshift, missense, nonsense mutations | 2-18 |

| SCAR1 | 9q34 | SETX | Senataxin | Frameshift, missense, nonsense mutations | 9-22 |

| SCAR2 | 9q34–qter | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Congenital |

| SCAR3 | 6p23–p21 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 3-52 |

| SCAR4 | 1p36 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 23-39 |

| SCAR5 | 15q24–q26 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 1-10 |

| SCAR6 | 20q11–q13 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Infancy |

| SCAR7 | 11p15 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Childhood |

| SCAR8 | 11p15 | SYNE1 | SYNE1 | Splice site mutation, nonsense mutations | 17-46 |

| SCAR9 | 1q41 | ADCK3 | ADCK3 | Splice site mutation, missense, nonsense mutations | 3-11 |

| Ataxia, Cayman type | 19q13.3 | ATCAY | Caytaxin | Missense mutation | Birth |

| IOSCA | 10q24 | C10orf2 | Twinkle | Missense, silent mutations | 9-24 mo |

| Progressive myoclonic epilepsy | 21q22.3 | CST6 | Cystatin B | 5′ dodecamer repeat | 6–13 |

| ARSACS | 13q12 | SACS | Sacsin | Frameshift and nonsense mutations | 1–20 |

| Congenital disorders of glycosylation | Multiple | Multiple | Multiple | Birth |

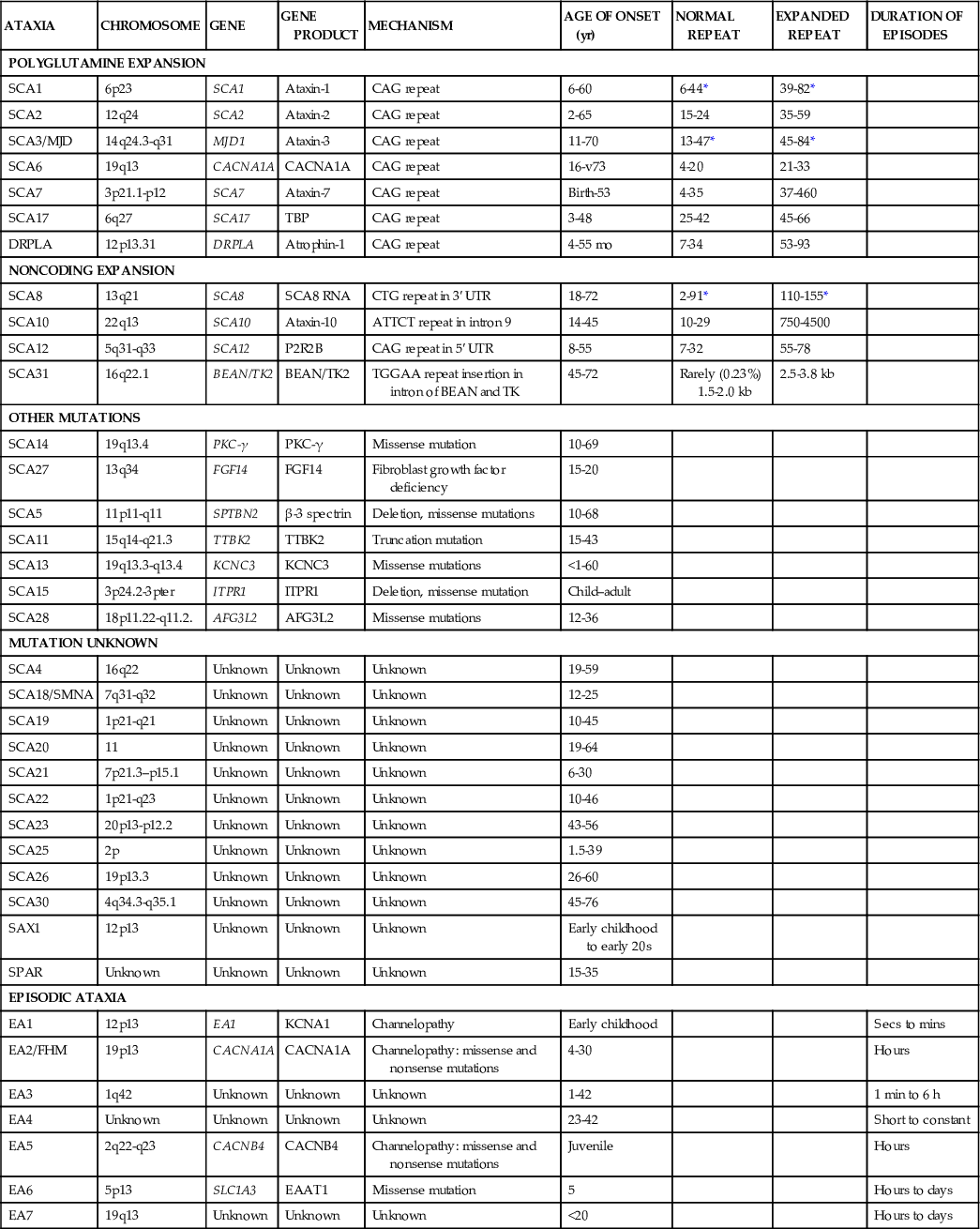

Table 597-5

Autosomal-Dominant Cerebellar Ataxias

| ATAXIA | CHROMOSOME | GENE | GENE PRODUCT | MECHANISM | AGE OF ONSET (yr) | NORMAL REPEAT | EXPANDED REPEAT | DURATION OF EPISODES |

| POLYGLUTAMINE EXPANSION | ||||||||

| SCA1 | 6p23 | SCA1 | Ataxin-1 | CAG repeat | 6-60 | 6-44* | 39-82* | |

| SCA2 | 12q24 | SCA2 | Ataxin-2 | CAG repeat | 2-65 | 15-24 | 35-59 | |

| SCA3/MJD | 14q24.3-q31 | MJD1 | Ataxin-3 | CAG repeat | 11-70 | 13-47* | 45-84* | |

| SCA6 | 19q13 | CACNA1A | CACNA1A | CAG repeat | 16-v73 | 4-20 | 21-33 | |

| SCA7 | 3p21.1-p12 | SCA7 | Ataxin-7 | CAG repeat | Birth-53 | 4-35 | 37-460 | |

| SCA17 | 6q27 | SCA17 | TBP | CAG repeat | 3-48 | 25-42 | 45-66 | |

| DRPLA | 12p13.31 | DRPLA | Atrophin-1 | CAG repeat | 4-55 mo | 7-34 | 53-93 | |

| NONCODING EXPANSION | ||||||||

| SCA8 | 13q21 | SCA8 | SCA8 RNA | CTG repeat in 3′ UTR | 18-72 | 2-91* | 110-155* | |

| SCA10 | 22q13 | SCA10 | Ataxin-10 | ATTCT repeat in intron 9 | 14-45 | 10-29 | 750-4500 | |

| SCA12 | 5q31-q33 | SCA12 | P2R2B | CAG repeat in 5′ UTR | 8-55 | 7-32 | 55-78 | |

| SCA31 | 16q22.1 | BEAN/TK2 | BEAN/TK2 | TGGAA repeat insertion in intron of BEAN and TK | 45-72 | Rarely (0.23%) 1.5-2.0 kb | 2.5-3.8 kb | |

| OTHER MUTATIONS | ||||||||

| SCA14 | 19q13.4 | PKC-γ | PKC-γ | Missense mutation | 10-69 | |||

| SCA27 | 13q34 | FGF14 | FGF14 | Fibroblast growth factor deficiency | 15-20 | |||

| SCA5 | 11p11-q11 | SPTBN2 | β-3 spectrin | Deletion, missense mutations | 10-68 | |||

| SCA11 | 15q14-q21.3 | TTBK2 | TTBK2 | Truncation mutation | 15-43 | |||

| SCA13 | 19q13.3-q13.4 | KCNC3 | KCNC3 | Missense mutations | <1-60 | |||

| SCA15 | 3p24.2-3pter | ITPR1 | ITPR1 | Deletion, missense mutation | Child–adult | |||

| SCA28 | 18p11.22-q11.2. | AFG3L2 | AFG3L2 | Missense mutations | 12-36 | |||

| MUTATION UNKNOWN | ||||||||

| SCA4 | 16q22 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 19-59 | |||

| SCA18/SMNA | 7q31-q32 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 12-25 | |||

| SCA19 | 1p21-q21 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 10-45 | |||

| SCA20 | 11 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 19-64 | |||

| SCA21 | 7p21.3–p15.1 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 6-30 | |||

| SCA22 | 1p21-q23 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 10-46 | |||

| SCA23 | 20p13-p12.2 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 43-56 | |||

| SCA25 | 2p | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 1.5-39 | |||

| SCA26 | 19p13.3 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 26-60 | |||

| SCA30 | 4q34.3-q35.1 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 45-76 | |||

| SAX1 | 12p13 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Early childhood to early 20s | |||

| SPAR | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 15-35 | |||

| EPISODIC ATAXIA | ||||||||

| EA1 | 12p13 | EA1 | KCNA1 | Channelopathy | Early childhood | Secs to mins | ||

| EA2/FHM | 19p13 | CACNA1A | CACNA1A | Channelopathy: missense and nonsense mutations | 4-30 | Hours | ||

| EA3 | 1q42 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 1-42 | 1 min to 6 h | ||

| EA4 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 23-42 | Short to constant | ||

| EA5 | 2q22-q23 | CACNB4 | CACNB4 | Channelopathy: missense and nonsense mutations | Juvenile | Hours | ||

| EA6 | 5p13 | SLC1A3 | EAAT1 | Missense mutation | 5 | Hours to days | ||

| EA7 | 19q13 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | <20 | Hours to days | ||

Signs and symptoms of ataxia include clumsiness, difficulty walking or sitting, falling to 1 side, slurred speech, hypotonia, intention tremor, dizziness, and delayed motor development. Genetic or chronic causes of cerebellar ataxia are often characterized by a long duration of symptoms, a positive family history, muscle weakness and abnormal gait, abnormal tone and strength, abnormal deep tendon reflexes, pes cavus, and sensory defects. Distinguishing ataxia from vestibular dysfunction may be difficult; however, labyrinth disorders are often characterized by severe vertigo, nausea and vomiting, position-induced vertigo, and a severe sense of unsteadiness.

Congenital anomalies of the posterior fossa, including the Dandy-Walker malformation, Chiari malformation, and encephalocele, are prominently associated with ataxia because of their destruction or replacement of the cerebellum (see Chapter 591.9). MRI is the method of choice for investigating congenital abnormalities of the cerebellum, vermis, and related structures. Agenesis of the cerebellar vermis presents in infancy with generalized hypotonia and decreased deep-tendon reflexes. Delayed motor milestones and truncal ataxia are typical. Joubert syndrome and related disorders are autosomal recessive disorders marked by developmental delay, hypotonia, abnormal eye movements, abnormal respirations, and a distinctive malformation of the cerebellum and brainstem that manifests as the “molar tooth sign” on MRI. Mutations in more than 21 different genes are associated with Joubert syndrome, but only approximately 50% of cases have a demonstrated causal mutation (see Chapter 591).

The major infectious causes of ataxia include cerebellar abscess, acute labyrinthitis, and acute cerebellar ataxia. Acute cerebellar ataxia occurs primarily in children 1-3 yr of age and is a diagnosis of exclusion. The condition often follows a viral illness, such as varicella virus, coxsackievirus, or echovirus infection by 2-3 wk and is thought to represent an autoimmune response to the viral agent affecting the cerebellum (see Chapters 250, 253, and 603). The onset is sudden, and the truncal ataxia can be so severe that the child is unable to stand or sit. Vomiting may occur initially, but fever and nuchal rigidity are absent. Horizontal nystagmus is evident in approximately 50% of cases and, if the child is able to speak, dysarthria may be impressive. Examination of the cerebrospinal fluid is typically normal at the onset of ataxia but a mild lymphocytic pleocytosis (10-30/mm3) is not unusual. Later in the course, the cerebrospinal fluid protein undergoes a moderate elevation. The ataxia begins to improve in a few weeks but may persist for as long as 3 mo and rarely longer than that. The incidence of acute cerebellar ataxia appears to have declined with increased rates of vaccination against varicella. The prognosis for complete recovery is excellent; a small number have long-term sequelae, including behavioral and speech disorders as well as ataxia and incoordination. Acute cerebellitis in contrast is a more severe form of cerebellar ataxia demonstrating abnormal MRI scans, more severe symptoms, and a poorer long-term prognosis. Infectious agents include Epstein-Barr virus, mycoplasma, mumps, and influenza virus, although in many the etiology is unknown; autoimmune cerebellitis may represent some of these unknown cases. Patients may present with ataxia, increased intracranial pressure from obstructive hydrocephalus, headache and fever. Acute labyrinthitis may be difficult to differentiate from acute cerebellar ataxia in a toddler. The condition is associated with middle-ear infections and presents with intense vertigo, vomiting, and abnormalities in labyrinthine function.

Toxic causes of ataxia include alcohol, thallium (which is used occasionally in homes as a pesticide), and the anticonvulsants, particularly phenytoin and carbamazepine when serum levels exceed the usual therapeutic range.

Brain tumors (see Chapter 497), including tumors of the cerebellum and frontal lobe, as well as peripheral nervous system neuroblastoma, may present with ataxia. Cerebellar tumors cause ataxia because of direct disruption of cerebellar function or indirectly because of increased intracranial pressure from compression of the fourth ventricle. Frontal lobe tumors may cause ataxia as a consequence of destruction of the association fibers connecting the frontal lobe with the cerebellum or because of increased intracranial pressure. Neuroblastoma (see Chapter 498) may be associated with a paraneoplastic encephalopathy characterized by progressive ataxia, myoclonic jerks, and opsoclonus (nonrhythmic, conjugate horizontal and vertical oscillations of the eyes).

Several metabolic disorders are characterized by ataxia, including abetalipoproteinemia, arginosuccinic aciduria, and Hartnup disease. Abetalipoproteinemia (Bassen-Kornzweig disease) begins in childhood with steatorrhea and failure to thrive (see Chapters 86.3 and 600). A blood smear shows acanthocytosis. Serum chemistries reveal decreased levels of cholesterol and triglycerides; serum β-lipoproteins are absent. Neurologic signs become evident by late childhood and consist of ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa, peripheral neuritis, abnormalities of position and vibration sense, muscle weakness, and intellectual disability. Vitamin E is undetectable in the serum of patients with neurologic symptoms.

Degenerative diseases of the central nervous system represent an important group of ataxic disorders of childhood because of the genetic consequences and poor prognosis. Ataxia-telangiectasia, an autosomal recessive condition, is the most common of the degenerative ataxias and is heralded by ataxia beginning at approximately age 2 yr and progressing to loss of ambulation by adolescence. Ataxia-telangiectasia is caused by mutations in the ATM gene located at 11q22-q23. ATM is a phosphytidylinositol-3 kinase that phosphorylates proteins involved in DNA repair and cell-cycle control. Oculomotor apraxia of horizontal gaze, defined as difficulty shifting gaze from one object to another and overshooting the target with lateral movement of the head, followed by refixating the eyes, is a frequent finding, as is strabismus, hypometric saccade pursuit abnormalities, and nystagmus. Ataxia-telangiectasia may present with chorea (see Chapter 597.2) rather than ataxia. The telangiectasia becomes evident by mid-childhood and is found on the bulbar conjunctiva, over the bridge of the nose, and on the ears and exposed surfaces of the extremities. Examination of the skin shows a loss of elasticity. Abnormalities of immunologic function that lead to frequent sinopulmonary infections include decreased serum and secretory immunoglobulin (Ig) A as well as diminished IgG2, IgG4, and IgE levels in more than 50% of patients. Children with ataxia-telangiectasia have a 50-100–fold increased risk of developing lymphoreticular tumors (lymphoma, leukemia, and Hodgkin disease) as well as brain tumors. Additional laboratory abnormalities include an increased incidence of chromosome breaks, particularly of chromosome 14, and elevated levels of α-fetoprotein. Death results from infection or tumor dissemination.

Friedreich ataxia is inherited as an autosomal-recessive disorder involving the spinocerebellar tracts, dorsal columns in the spinal cord, the pyramidal tracts, and the cerebellum and medulla. The majority of patients are homozygous for a GAA repeat expansion in the noncoding region of the gene coding for the mitochondrial protein frataxin. Mutations cause oxidative injury associated with excessive iron deposits in mitochondria. The onset of ataxia is somewhat later than in ataxia-telangiectasia, but usually occurs before age 10 yr. The ataxia is slowly progressive and involves the lower extremities to a greater degree than the upper extremities. The Romberg test result is positive; the deep-tendon reflexes are absent (particularly at the ankle), and the plantar response is typically extensor (Babinski sign). Patients develop a characteristic explosive, dysarthric speech, and nystagmus is present in most children. Although patients may appear apathetic, their intelligence is preserved. They may have significant weakness of the distal musculature of the hands and feet. Marked loss of vibration and joint position sense is common and is caused by degeneration of the posterior columns. Friedreich ataxia is also characterized by skeletal abnormalities, including high-arched feet (pes cavus) and hammertoes, as well as progressive kyphoscoliosis. Results of electrophysiologic studies, including visual, auditory brainstem, and somatosensory-evoked potentials, are often abnormal. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with progression to intractable congestive heart failure is the cause of death for most patients.

Several forms of spinocerebellar ataxia are similar to Friedreich ataxia but are less common. Roussy-Levy disease has, in addition to ataxia, atrophy of the muscles of the lower extremity with a pattern of wasting similar to that observed in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease; Ramsay Hunt syndrome has an associated myoclonic epilepsy.

There are more than 20 dominantly inherited spinocerebellar ataxias, some of which present in childhood. These include those associated with CAG (polyglutamine) repeats and noncoding microsatellite expansions. Dominantly inherited episodic ataxias caused by potassium or calcium channel dysfunction present as episodes of ataxia and muscle weakness. Some of these disorders may respond to acetazolamide. The dominantly inherited olivopontocerebellar atrophies include ataxia, cranial nerve palsies, and abnormal sensory findings in the 2nd or 3rd decade, but can present in children with rapidly progressive ataxia, nystagmus, dysarthria, and seizures.

Additional degenerative ataxias include Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease, neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses, and late-onset GM2 gangliosidosis (see Chapters 86.4 and 600). Rare forms of progressive cerebellar ataxia have been described in association with vitamin E deficiency. A number of autosomal-dominant progressive spinocerebellar ataxias have been defined at the molecular level, including those caused by unstable trinucleotide repeat expansions.

Chorea, Athetosis, Tremor

Rebecca K. Lehman, Jonathan W. Mink

Chorea, meaning “dance-like” in Greek, refers to rapid, chaotic movements that seem to flow from 1 body part to another. Affected individuals exhibit motor impersistence, with difficulty keeping the tongue protruded (“darting tongue”) or maintaining grip (“milkmaid grip”). Chorea tends to occur both at rest and with action. Patients often attempt to incorporate the involuntary movements into more purposeful movements, making them appear fidgety. Chorea increases with stress and disappears in sleep. Chorea can be divided into primary (i.e., disorders in which chorea is the dominant symptom and the etiology is presumed to be genetic) and secondary forms, with the vast majority of pediatric cases falling into the latter category (Tables 597-6 and 597-7).

Table 597-6

Etiologic Classification of Choreic Syndromes

| GENETIC CHOREAS |

Huntington disease (rarely presents with chorea in childhood) Huntington disease–like 2 and other Huntington disease –like syndromes Dentatorubropallidoluysian atrophy Leigh syndrome and other mitochondrial disorders Spinocerebellar ataxia (types 2, 3, or 17) Pantothene kinase–associated neurodegeneration (PKAN) Paroxysmal kinesigenic choreoathetosis |

| STRUCTURAL BASAL-GANGLIA LESIONS |

| PARAINFECTIOUS AND AUTOIMMUNE DISORDERS |

| INFECTIOUS CHOREA |

| METABOLIC DRUG OR TOXIC ENCEPHALOPATHIES |

| DRUG-INDUCED CHOREA (see Table 597-8) |

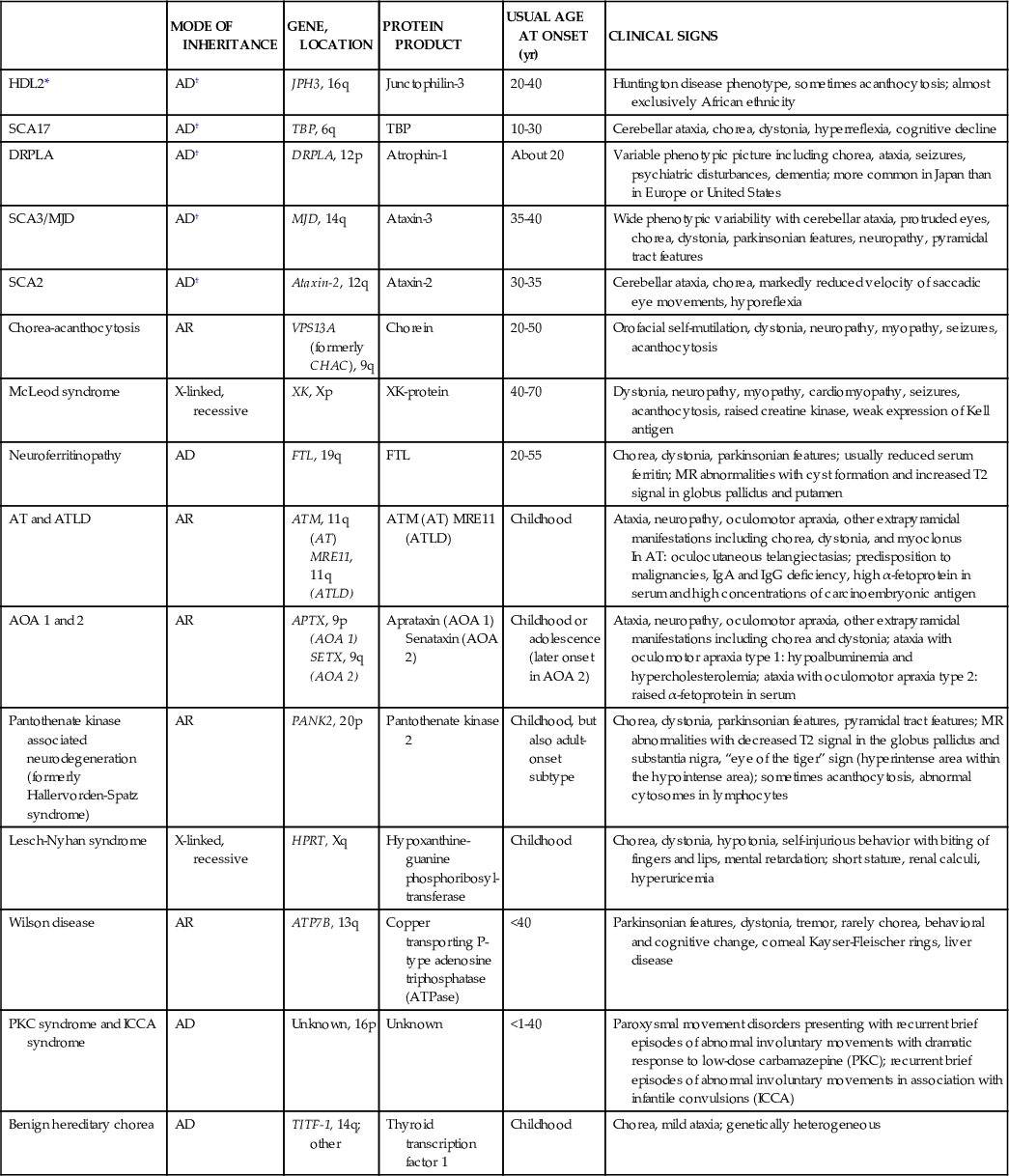

Table 597-7

Genetic Choreas

| MODE OF INHERITANCE | GENE, LOCATION | PROTEIN PRODUCT | USUAL AGE AT ONSET (yr) | CLINICAL SIGNS | |

| HDL2* | AD† | JPH3, 16q | Junctophilin-3 | 20-40 | Huntington disease phenotype, sometimes acanthocytosis; almost exclusively African ethnicity |

| SCA17 | AD† | TBP, 6q | TBP | 10-30 | Cerebellar ataxia, chorea, dystonia, hyperreflexia, cognitive decline |

| DRPLA | AD† | DRPLA, 12p | Atrophin-1 | About 20 | Variable phenotypic picture including chorea, ataxia, seizures, psychiatric disturbances, dementia; more common in Japan than in Europe or United States |

| SCA3/MJD | AD† | MJD, 14q | Ataxin-3 | 35-40 | Wide phenotypic variability with cerebellar ataxia, protruded eyes, chorea, dystonia, parkinsonian features, neuropathy, pyramidal tract features |

| SCA2 | AD† | Ataxin-2, 12q | Ataxin-2 | 30-35 | Cerebellar ataxia, chorea, markedly reduced velocity of saccadic eye movements, hyporeflexia |

| Chorea-acanthocytosis | AR | VPS13A (formerly CHAC), 9q | Chorein | 20-50 | Orofacial self-mutilation, dystonia, neuropathy, myopathy, seizures, acanthocytosis |

| McLeod syndrome | X-linked, recessive | XK, Xp | XK-protein | 40-70 | Dystonia, neuropathy, myopathy, cardiomyopathy, seizures, acanthocytosis, raised creatine kinase, weak expression of Kell antigen |

| Neuroferritinopathy | AD | FTL, 19q | FTL | 20-55 | Chorea, dystonia, parkinsonian features; usually reduced serum ferritin; MR abnormalities with cyst formation and increased T2 signal in globus pallidus and putamen |

| AT and ATLD | AR | ATM, 11q (AT) MRE11, 11q (ATLD) | ATM (AT) MRE11 (ATLD) | Childhood | Ataxia, neuropathy, oculomotor apraxia, other extrapyramidal manifestations including chorea, dystonia, and myoclonus In AT: oculocutaneous telangiectasias; predisposition to malignancies, IgA and IgG deficiency, high α-fetoprotein in serum and high concentrations of carcinoembryonic antigen |

| AOA 1 and 2 | AR | APTX, 9p (AOA 1) SETX, 9q (AOA 2) | Aprataxin (AOA 1) Senataxin (AOA 2) | Childhood or adolescence (later onset in AOA 2) | Ataxia, neuropathy, oculomotor apraxia, other extrapyramidal manifestations including chorea and dystonia; ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 1: hypoalbuminemia and hypercholesterolemia; ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2: raised α-fetoprotein in serum |

| Pantothenate kinase associated neurodegeneration (formerly Hallervorden-Spatz syndrome) | AR | PANK2, 20p | Pantothenate kinase 2 | Childhood, but also adult-onset subtype | Chorea, dystonia, parkinsonian features, pyramidal tract features; MR abnormalities with decreased T2 signal in the globus pallidus and substantia nigra, “eye of the tiger” sign (hyperintense area within the hypointense area); sometimes acanthocytosis, abnormal cytosomes in lymphocytes |

| Lesch-Nyhan syndrome | X-linked, recessive | HPRT, Xq | Hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl-transferase | Childhood | Chorea, dystonia, hypotonia, self-injurious behavior with biting of fingers and lips, mental retardation; short stature, renal calculi, hyperuricemia |

| Wilson disease | AR | ATP7B, 13q | Copper transporting P-type adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) | <40 | Parkinsonian features, dystonia, tremor, rarely chorea, behavioral and cognitive change, corneal Kayser-Fleischer rings, liver disease |

| PKC syndrome and ICCA syndrome | AD | Unknown, 16p | Unknown | <1-40 | Paroxysmal movement disorders presenting with recurrent brief episodes of abnormal involuntary movements with dramatic response to low-dose carbamazepine (PKC); recurrent brief episodes of abnormal involuntary movements in association with infantile convulsions (ICCA) |

| Benign hereditary chorea | AD | TITF-1, 14q; other | Thyroid transcription factor 1 | Childhood | Chorea, mild ataxia; genetically heterogeneous |

Sydenham chorea (St. Vitus dance) is the most common acquired chorea of childhood. It occurs in 10-20% of patients with acute rheumatic fever, typically weeks to months after a group A β-hemolytic streptococcal infection (see Chapter 183.1). Peak incidence is at age 8-9 yr, with a female predominance of 2 : 1. There is evidence that group A β-hemolytic streptococci promote the generation of cross-reactive or polyreactive antibodies through molecular mimicry between streptococcal and host antigens. Specifically, antibodies against the N-acetyl-β-D-glucosamine epitope (GlcNAc) of streptococcal group A carbohydrate target intracellular β-tubulin and extracellular lysoganglioside GM1 in human caudate-putamen preparations. These antibodies are also capable of directing calcium/calmodulin–dependent protein kinase II activation, which may cause the neurologic manifestations of Sydenham chorea by increasing dopamine release into the synapse.

The clinical hallmarks of Sydenham chorea are chorea, hypotonia, and emotional lability. Onset of the chorea is usually insidious but may be abrupt. Most patients have generalized chorea but the majority have asymmetric manifestations and up to 20% have hemichorea. Hypotonia manifests with the “pronator sign” (arms and palms turn outward when held overhead) and the “choreic hand” (spooning of the extended hand by flexion of the wrist and extension of the fingers). When chorea and hypotonia are severe, the child may be incapable of feeding, dressing, or walking without assistance. Speech is often involved, sometimes to the point of being unintelligible. Periods of uncontrollable crying and extreme mood swings are characteristic and may precede the onset of the movement disorder.

Sydenham chorea is a clinical diagnosis; a combination of acute and convalescent serum antistreptolysin O titers may help to confirm an acute streptococcal infection. Negative titers do not exclude the diagnosis. All patients with Sydenham chorea should be evaluated for carditis and started on long-term antibiotic prophylaxis (e.g., penicillin G benzathine 1.2 million units IM every 4 wk or penicillin V 250 mg PO twice daily) to decrease the risk of rheumatic heart disease with recurrence. For patients with chorea that is impairing, treatment options include valproate, carbamazepine, and dopamine receptor antagonists. Historically, there have been conflicting data regarding the efficacy of prednisone, intravenous immunoglobulin, and other immunomodulatory agents in Sydenham chorea, making it difficult to recommend their routine use. A more recent randomized, double-blinded study of 37 children with Sydenham chorea compared high-dose prednisone (2 mg/kg/day, max: 60 mg) for 4 wk vs a placebo and found that steroids significantly reduced time to remission (54.3 days vs 119.9 days in controls). There is no evidence that treatment with prednisone alters recurrence rate or long-term outcome.

Sydenham chorea usually resolves spontaneously within 6-9 mo, although it can persist for up to 2 yr and, in rare cases, can remain a lifelong condition. Relapse in the 1st few yr is relatively common, occurring in 37.9% of patients in 1 series. Remote recurrence of chorea is rare, but may be provoked by streptococcal infections, pregnancy (chorea gravidarum), or oral contraceptive use.

Although much rarer than Sydenham chorea, systemic lupus erythematosus (see Chapter 158) is a well-known cause of chorea in children. In some cases, chorea may be the presenting sign of systemic lupus erythematosus. A recent retrospective study of a large pediatric lupus cohort examined the prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies and evaluated their association with neuropsychiatric symptoms. There was a significant association between a persistently positive lupus anticoagulant and chorea (p = 0.02); however, only 2 of the 137 patients in the cohort had chorea. Regardless, a child with chorea of unknown cause should be investigated for the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies.

Additional causes of secondary chorea include metabolic (hyperthyroidism, hypoparathyroidism), infectious (Lyme disease), immune-mediated (systemic lupus erythematosus; anti–N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antibody syndrome), vascular (stroke, moyamoya disease), heredodegenerative disorders (Wilson disease), and drugs (Table 597-8). Although chorea is a hallmark of Huntington disease in adults, children who develop Huntington disease tend to present with rigidity and bradykinesia (Westphal variant) or dystonia rather than chorea.

Table 597-8

Drugs That Can Induce Chorea

| DOPAMINE RECEPTOR BLOCKING AGENTS (UPON WITHDRAWAL OR AS A TARDIVE SYNDROME) |

| ANTIPARKINSONIAN DRUGS |

| ANTIEPILEPTIC DRUGS |

| PSYCHOSTIMULANTS |

| CALCIUM CHANNEL BLOCKERS |

| OTHERS |

Athetosis is characterized by slow, continuous, writhing movements that repeatedly involve the same body part(s), usually the distal extremities, face, neck, or trunk. Like chorea, athetosis may occur at rest and is often worsened by voluntary movement. Because athetosis tends to co-occur with other movement disorders, such as chorea (choreoathetosis) and dystonia, it is often difficult to distinguish as a discrete entity. Choreoathetosis is associated with cerebral palsy, kernicterus, and other forms of basal ganglia injury; therefore, it is often seen in conjunction with rigidity—increased muscle tone that is equal in the flexors and extensors in all directions of passive movement regardless of the velocity of the movement. This is to be differentiated from spasticity, a velocity-dependent (“clasp-knife”) form of hypertonia that is seen with upper motor neuron dysfunction. As with chorea, athetosis/choreoathetosis can also be seen with hypoxic-ischemic injury and dopamine-blocking drugs.

Tremor is a rhythmic, oscillatory movement around a central point or plane that results from the action of antagonist muscles. Tremor can affect the extremities, head, trunk, or voice and can be classified by both its frequency (slow [4 Hz], intermediate [4-7 Hz], and fast [>7 Hz]) and by the context in which it is most pronounced. Rest tremor is maximal when the affected body part is inactive and supported against gravity, whereas postural tremor is most notable when the patient sustains a position against gravity. Action tremor occurs with performance of a voluntary activity and can be subclassified into simple kinetic tremor, which occurs with limb movement, and intention tremor, which occurs as the patient's limb approaches a target and is a feature of cerebellar disease.

Essential tremor (ET) is the most common movement disorder in adults, and 50% of persons diagnosed with ET report an onset in childhood; thus ET may be the most common tremor disorder in children as well. Clinical experience in pediatric movement disorders clinic suggests that ET is more common in the pediatric population than the literature would suggest. ET is an autosomal-dominant condition with variable expressivity but complete penetrance by the age of 60 yr. Although the genetics of ET are not fully understood, at least 3 different genes—EMT1 on chromosome 3q13, EMT2 on chromosome 2p22-25, and LINGO1 on chromosome 15q24—are linked to the condition. Based on functional imaging studies, the defect is thought to localize to cerebellar circuits.

ET is characterized by a slowly progressive, bilateral, 4-9 Hz postural tremor that involves the upper extremities and occurs in the absence of other known causes of tremor. Mild asymmetry is common, but ET is rarely unilateral. ET may be worsened by actions, such as trying to pour water from cup to cup. Affected adults may report a history of ethanol responsiveness. Most young children present for evaluation because a parent, teacher, or therapist has noticed the tremor, rather than because the tremor causes impairment. Most children with ET do not require pharmacologic intervention. If they are having difficulty with their handwriting or self-feeding, an occupational therapy evaluation and/or assistive devices, such as wrist weights and weighted silverware, may be helpful. Teenagers tend to report more impairment from ET. Teenagers who do require pharmacotherapy usually respond to the same medications that are used in adults—propranolol and primidone. Propranolol, which is generally considered the first-line treatment, can be started at 20–40 mg daily and titrated to effect, with most patients responding to doses of 60-80 mg/day. Propranolol should not be used in patients with reactive airway disease. Primidone can be started at 12.5-25 mg at bedtime and increased gradually in a twice daily schedule. Most patients respond to doses of 50-200 mg/day. Other treatments options for ET reported in the adult literature include atenolol, gabapentin, topiramate, and alprazolam. Surgical treatments, which include deep brain stimulation of the thalamus and unilateral thalamotomy, are generally reserved for adults with medically refractory disabling tremor.

In addition to ET, there are numerous secondary etiologies of tremor in children (Table 597-9). Holmes tremor, previously referred to as midbrain or rubral tremor, is characterized by a slow frequency, high-amplitude tremor that is present at rest and with intention. It is a symptomatic tremor, which usually results from lesions of the brainstem, cerebellum, or thalamus. Psychogenic tremor is distinguished by its variable appearance, abrupt onset and remission, nonprogressive course, and association with selective but not task-specific disabilities. In some cases, tremor may even occur as a manifestation of another movement disorder, as is seen with position- or task-specific tremor (e.g., writing tremor), dystonic tremor, and myoclonic tremor.

Table 597-9

Selected Causes of Tremor in Children

| BENIGN |

| STATIC INJURY/STRUCTURAL |

| HEREDITARY/DEGENERATIVE |

| METABOLIC |

| DRUGS/TOXINS |

| Valproate, phenytoin, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, gabapentin, lithium, tricyclic antidepressants, stimulants (cocaine, amphetamine, caffeine, thyroxine, bronchodilators), neuroleptics, cyclosporine, toluene, mercury, thallium, amiodarone, nicotine, lead, manganese, arsenic, cyanide, naphthalene, ethanol, lindane, serotonin reuptake inhibitors |

| PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHIES |

| PSYCHOGENIC |

When evaluating a child with tremor, it is important to screen for common metabolic disturbances, including electrolyte abnormalities and thyroid disease, assess the child's caffeine intake, and review the child's medication list for known tremor-inducing agents. It is also critical to exclude Wilson disease in teenagers with characteristic “wing-beating” tremor, as this is a treatable condition.

Dystonia

Erika F. Augustine, Jonathan W. Mink

Dystonia is a disorder of movement characterized by sustained muscle contraction, frequently causing twisting and repetitive movements or abnormal postures. Major causes of dystonia include primary generalized dystonia, medications, metabolic disorders, and perinatal asphyxia (Tables 597-10 and 597-11).

Table 597-10

Causes of Dystonia in Childhood

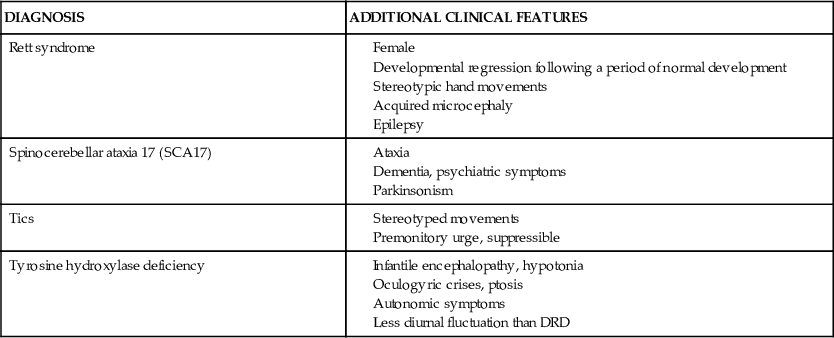

Table 597-11

Examples of Primary and Secondary Dystonia in Childhood

| DIAGNOSIS | ADDITIONAL CLINICAL FEATURES |

| Aicardi-Goutières syndrome | |

| Alternating hemiplegia of childhood | |

| Aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency (AADC) | |

| ARX gene mutation (X-linked) | |

| Benign paroxysmal torticollis of infancy | |

| Complex regional pain syndrome | |

| Dopa-responsive dystonia (DRD) | Diurnal variation |

| Drug-induced dystonia | |

| Dystonia-deafness optic neuropathy syndrome | |

| DYT1 dystonia | Lower limb onset followed by generalization |

| Glutaric aciduria type 1 | |

| GM1 gangliosidosis type 3 | |

| Huntington disease | |

| Kernicterus | |

| Leigh syndrome | |

| Lesch-Nyhan syndrome (X-linked) | |

| Myoclonus dystonia | |

| Niemann-Pick type C | |

| Neuroacanthocytosis | Oromandibular and lingual dystonia |

| Neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation | |

| Rapid onset dystonia parkinsonism (DYT12) | |

| Rett syndrome | |

| Spinocerebellar ataxia 17 (SCA17) | |

| Tics | |

| Tyrosine hydroxylase deficiency |

Inherited Primary Dystonias

Primary generalized dystonia, also referred to as primary torsion dystonia or dystonia musculorum deformans, is caused by a group of genetic disorders with onset in childhood. One form, which occurs more commonly in the Ashkenazi Jewish population, is caused by a dominant mutation in the DYT1 gene coding for the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding protein torsinA. The initial manifestation of DYT1 dystonia is often intermittent unilateral posturing of a lower extremity, which assumes an extended and rotated position. Ultimately, all 4 extremities and the axial musculature can be affected, but the dystonia may also remain localized to one limb. Cranial involvement can occur in DYT1 dystonia, but it is uncommon compared to non-DYT1 dystonias. There is a wide clinical spectrum, varying even within families. If a family history of dystonia is absent, the diagnosis should still be considered, given the intrafamilial variability in clinical expression.

More than a dozen loci for genes for torsion dystonia have been identified (DYT1-DYT24). One is the autosomal dominant disorder dopa-responsive dystonia (DRD, DYT5a), also called Segawa syndrome. The gene for DRD codes for guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase 1, the rate-limiting enzyme for tetrahydrobiopterin synthesis, which is a cofactor for synthesis of the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin. Thus, the genetic mutation results in dopamine deficiency. The hallmark of the disorder, particularly in adolescents and adults, is diurnal variation: symptoms worsen as the day progresses and may transiently improve with sleep. Early-onset patients, who tend to present with delayed or abnormal gait from dystonia of a lower extremity, can easily be confused with patients with dystonic cerebral palsy. It should be noted that in the presence of a progressive dystonia, diurnal fluctuation, or if loss of previously achieved motor skills occurs, a prior diagnosis of cerebral palsy should be reexamined. DRD responds dramatically to small daily doses of levodopa. The responsiveness to levodopa is a sustained benefit, even if the diagnosis is delayed several years, as long as contractures have not developed.

Myoclonus dystonia (DYT11), caused by mutations in the epsilon-sarcoglycan (SCGE) gene, is characterized by dystonia involving the upper extremities, head, and/or neck, as well as myoclonic movements in these regions. Although a combination of myoclonus and dystonia typically occurs, each manifestation can present in isolation. When repetitive, the myoclonus may take on a tremor-like appearance, termed dystonic tremor. Improvement in symptoms following alcohol ingestion, reported by affected adult family members, may be a helpful clue to this diagnosis.

Common to the inherited dystonias, there is considerable intrafamilial variability in clinical manifestations, distribution, and severity of dystonia. In primary dystonias, although the main clinical features are motor, there may be an increased risk for major depression. Anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and depression have all been reported in the myoclonus–dystonia syndrome. Screening for psychiatric comorbidities cannot be overlooked in this population.

Drug-Induced Dystonias

A number of medications are capable of inducing involuntary movements, drug-induced movement disorders, in children and adults. Dopamine-blocking agents, including antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol) and antiemetics (e.g., metoclopramide, prochlorperazine), as well as atypical antipsychotics (e.g., risperidone) can produce acute dystonic reactions or delayed (tardive) drug-induced movement disorders. Acute dystonic reactions, occurring in the 1st days of exposure, typically involve the face and neck, manifesting as torticollis, retrocollis, oculogyric crisis, or tongue protrusion. Life-threatening presentations with laryngospasm and airway compromise can also occur, requiring prompt recognition and treatment of this entity. Intravenous diphenhydramine, 1-2 mg/kg/dose, may rapidly reverse the drug-related dystonia. The high potency of the dopamine blocker, young age, and prior dystonic reactions may be predisposing factors. Acute dystonic reactions have also been described with cetirizine.

Severe rigidity combined with high fever, autonomic symptoms (tachycardia, diaphoresis), delirium, and dystonia are signs of neuroleptic malignant syndrome, which typically occurs a few days after starting or increasing the dose of a neuroleptic drug, or in the setting of withdrawal from a dopaminergic agent. In contrast to acute dystonic reactions, which take place within days, neuroleptic malignant syndrome occurs within a month of medication initiation or dose increase.

Delayed onset involuntary movements, tardive dyskinesias, develop in the setting of chronic (>3 mo duration) neuroleptic use. Involvement of the face, particularly the mouth, lips, and/or jaw with chewing or tongue thrusting is characteristic. The risk of tardive dyskinesia, which is much less frequent in children compared to adults, increases as medication dose and duration of treatment increase. There are data to suggest that children with autism spectrum disorders may also be at increased risk for this drug-induced movement disorders. Unlike acute dystonic reactions and neuroleptic malignant syndrome, discontinuation of the offending agent may not result in clinical improvement. In these patients, use of dopamine-depletors, such as reserpine or tetrabenazine, may prove helpful.

Therapeutic doses of phenytoin or carbamazepine rarely cause progressive dystonia in children with epilepsy, particularly in those who have an underlying structural abnormality of the brain.

During evaluation of new onset dystonia, a careful history of prescriptions and potential medication exposures is critical.

Cerebral Palsy

See Chapter 598.

Metabolic Disorders

Disorders of monamine neurotransmitter metabolism, of which DRD is one, present in infancy and early childhood with dystonia, hypotonia, oculogyric crises, and/or autonomic symptoms. The more common disorders among this group of rare diseases include DRD, tyrosine hydroxylase deficiency, and aromatic amino acid decarboxylase deficiency. Abnormalities of the dopamine transporter (DAT) can also present in infancy with dystonia. Detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter; reviews, however, are available for reference.

Wilson disease is an autosomal recessive inborn error of copper transport characterized by cirrhosis of the liver and degenerative changes in the central nervous system, particularly the basal ganglia (see Chapter 357.2). It has been determined that there are multiple mutations in the Wilson disease gene (WND), accounting for the variability in presentation of the condition. The neurologic manifestations of Wilson disease rarely appear before age 10 yr, and the initial sign is often progressive dystonia. Tremors of the extremities develop, unilaterally at first, but they eventually become coarse, generalized, and incapacitating. Other neurologic signs of Wilson disease relate to progressive basal ganglia disease, such as parkinsonism, dysarthria, dysphonia, and choreoathetosis. Less frequent are ataxia and pyramidal signs. The MRI or CT scan shows ventricular dilation in advanced cases with atrophy of the cerebrum, cerebellum, and/or brainstem, along with signal intensity change in the basal ganglia, thalamus, and/or brainstem, particularly the midbrain.

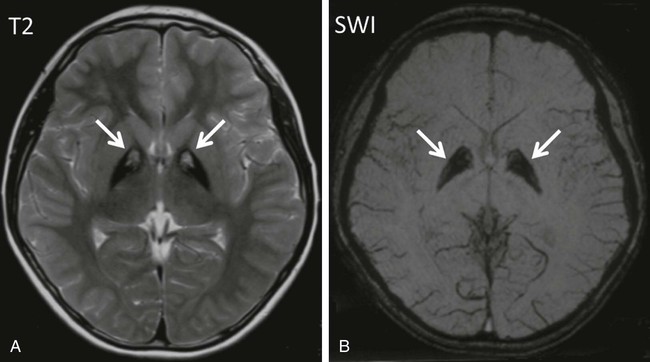

Pantothenate kinase–associated neurodegeneration (formerly known as Hallervorden-Spatz disease) is a rare autosomal recessive neurodegenerative disorder. Many patients have mutations in pantothenate kinase 2 (PANK2) localized to mitochondria in neurons. The condition usually begins before 6 yr of age and is characterized by rapidly progressive dystonia, rigidity, and choreoathetosis. Spasticity, extensor plantar responses, dysarthria, and intellectual deterioration become evident during adolescence, and death usually occurs by early adulthood. MRI shows lesions of the globus pallidus, including low signal intensity in T2-weighted images (corresponding to iron pigments) and an anteromedial area of high signal intensity (tissue necrosis and edema), or “eye-of-the-tiger” sign (Fig. 597-1). Neuropathologic examination indicates excessive accumulation of iron-containing pigments in the globus pallidus and substantia nigra. More recently, similar disorders of high brain iron content without PANK2 mutations, including infantile neuroaxonal dystrophy, neuroferritinopathy, and aceruloplasminemia, have been grouped as disorders of neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Patterns of iron deposition visualized by brain MRI have shown utility in differentiating these disorders.

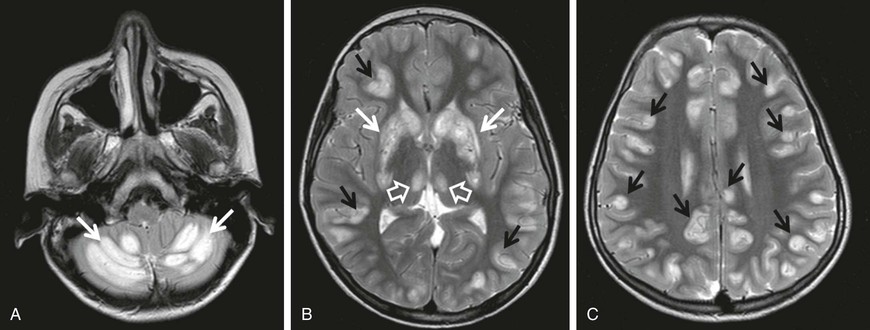

Biotin-responsive basal ganglia disease manifests with episodes of acute dystonia, external ophthalmoplegia and encephalopathy. SLC19A3 is the responsible mutated gene. MRI demonstrates involvement of the basal ganglia, with vasogenic edema and the “bat-wing” sign (Fig. 597-2). Treatment with biotin and thiamine results in improvement in 2-4 days.

Although dystonia may present in isolation as the first sign of a metabolic or neurodegenerative disorder, this group of diseases should be considered mainly in those who demonstrate signs of systemic disease, (e.g., organomegaly, short stature, hearing loss, vision impairment, epilepsy), those with episodes of severe illness, evidence of regression, or cognitive impairment. Table 597-11 outlines additional features suggestive of specific disorders.

Other Disorders

Although uncommon, movement disorders, including dystonia, may be part of the presenting symptoms of complex regional pain syndrome. Onset of involuntary movements within 1 yr of the traumatic event, affected lower limb, pain disproportionate to inciting event, and changes in the overlying skin and blood flow to the affected area suggest complex regional pain syndrome. Although sustained dystonia can produce pain or discomfort, complex regional pain syndrome should be considered in those who have a prominent component of pain and recent history of trauma to the affected limb.

There are disorders unique to childhood that warrant exploration in this section. Benign paroxysmal torticollis of infancy is characterized by recurrent episodes of cervical dystonia beginning in the 1st few mo of life. The torticollis may alternate sides from 1 episode to the next and may also persist during sleep. Associated signs and symptoms include irritability, pallor, vomiting, vertigo, ataxia, and occasionally limb dystonia. Family history is often notable for migraine and/or motion sickness in 1st-degree relatives. Despite the high frequency of spells, imaging studies are normal, and the outcome is uniformly benign with resolution by 3 yr of age.

In alternating hemiplegia of childhood, episodic hemiplegia affecting either side of the body is the hallmark of the disorder. However, patients are also affected by episodes of dystonia, ranging from minutes to days in duration. On average, both features of the disorder commence at approximately 6 mo of age. Episodic abnormal eye movements are observed in a large proportion of patients (93%) with onset as early as the 1st wk of life. Alternating hemiplegia of childhood is associated with mutations in the ATP1A2 and ATP1A3 genes. Alternating hemiplegia of childhood can similarly be triggered by fluctuations in temperature, certain foods, or water exposure. Over time, epilepsy and cognitive impairment emerge, and the involuntary movements change from episodic to constant. Infantile onset and the paroxysmal nature of symptoms early in the disease course are key features to this diagnosis.

Finally, although a diagnosis of exclusion, the presence of odd movements or selective disability may indicate a psychogenic dystonia in older children. There is considerable overlap in features of organic and psychogenic movement disorders, making the diagnosis difficult to establish. For instance, both organic and psychogenic movement disorders have the potential to worsen in the setting of stress and may dissipate with relaxation or sleep. History should include review of recent stressors, psychiatric symptoms, and exposure to others with similar disorders. On examination, a changing movement disorder, inconsistent motor or sensory exam, or response to suggestion, are supportive of a possible psychogenic movement disorder. Early recognition of this disorder may lessen morbidity caused by unnecessary diagnostic and interventional procedures.

Treatment

Children with generalized dystonia, including those with involvement of the muscles of swallowing, may respond to the anticholinergic agent trihexyphenidyl (Artane). Titration occurs slowly over the course of months in an effort to limit untoward side effects, such as urinary retention, mental confusion, or blurred vision. Additional drugs that have been effective include levodopa and diazepam. Segmental dystonia, such as torticollis, often responds well to botulinum toxin injections. Intrathecal baclofen delivered through implantable constant infusion pump may be helpful in some patients. Deep brain stimulation with leads implanted in the globus pallidus is most helpful for children with severe primary generalized dystonia. Recent data suggest, however, that deep brain stimulation may also be of benefit in children with secondary dystonias, such as cerebral palsy.

In the case of drug-induced dystonias, removal of the offending agent and treatment with intravenous diphenhydramine typically suffices. For neuroleptic malignant syndrome, dantrolene may be indicated.