Depression

Unipolar depressive disorders (depression without a manic or hypomanic phase) not associated with medical illness are typically classified as follows in various diagnostic manuals:

• Major depression characterised by sadness, apathy, irritability, disturbed sleep, disturbed appetite, weight loss, fatigue, poor concentration, guilt and thoughts of death

• Dysthymic disorder, which consists of a pattern of chronic, ongoing mild depressive symptoms that are less severe than major depression

• Seasonal affective disorder (SAD), which is more common in women and related to seasonal changes. The prevalence increases with increasing latitude and it can be treated by light therapy. Symptoms include lack of energy, weight gain and carbohydrate craving.

The DSM-IV defines major depressive disorder (MDD) as a clinical depressive episode that lasts longer than 2 weeks and is uncomplicated by recent grief, substance abuse or a medical disorder.78 Various theories about the cause of MDD have been proposed, and include the monoamine-deficiency hypothesis (that underlies modern drug therapy) and a dysfunction in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis with an abnormal stress response.80 Elevated cortisol is consistently present in depressed patients. This overactivity of the HPA axis may be related to a conditioned response to traumatic events in childhood.

MDD has various degrees of expression, and phytotherapy is most appropriate for its mild to moderate manifestations. Patients experiencing severe MDD with acute suicidal thoughts or exhibiting other forms of self-endangerment should be referred to appropriate care. Impaired circulation to the brain, especially in elderly patients, is another cause of depression. Low systolic blood pressure was also associated with a poor perception of well-being in 50-year-old men81 and depression in men aged 60 to 89 years.82

The general considerations outlined in the treatment of anxiety also apply here. Patients suffering from depression should be treated as a whole with due attention to lifestyle, diet, drug use and mental hygiene (productive attitudes for coping with life events). Professional guidance and counselling is often appropriate, rather than the relegation of depression to just a biochemical imbalance to be corrected with pharmacological agents.

As noted above, phytotherapy is most appropriate for mild to moderate episodes of MDD, dysthymic disorder and SAD. Episodes of severe depression may require the more strident therapy offered by conventional drugs, although herbs can have a supportive role, especially in terms of boosting vitality. Herbs can also be relevant when the patient has improved and wishes to discontinue drug therapy.

Key elements of herbal treatment are as follows:

• The nervine tonic herbs are the mainstay of treatment, especially St John’s wort, which is a well-proven treatment for mild to moderate depression (see monograph). Other important herbs in this category include damiana, skullcap, Schisandra and Bacopa.

• Patients who are also anxious should be prescribed anxiolytic herbs. Valerian, passionflower and Zizyphus are also useful, but hops is traditionally contraindicated.

• Depressed patients are low in vitality, so adrenal restorative (licorice and Rehmannia), tonic and adaptogenic herbs are often indicated. Ginseng may have antidepressant activity, but it should be used cautiously if anxiety is present. Rhodiola, Withania and Siberian ginseng are better choices in these cases. Licorice and Schisandra also have exhibited some antidepressant activity in animal models. These herbs will also help correct the adverse long-term effects of stress on the physiology of the stress response.

• If required, herbs that improve circulation to the brain should be prescribed, especially Ginkgo.

• Recent research supports the value of lavender, Rhodiola and saffron (see above).

Example liquid formula

| Valeriana officinalis | 1:2 | 20 mL |

| Hypericum perforatum | 1:2 | 25 mL |

| Rhodiola rosea | 2:1 | 20 mL |

| Schisandra chinensis | 1:2 | 20 mL |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra | 1:1 | 15 mL |

| total | 100 mL |

Dose: 5 mL with water three times a day.

Case history

A male patient, aged 72, came seeking help for depression following the death of his daughter from cancer about 6 months ago. He did not want to take conventional medication. He was prescribed St John’s wort extract 300 mg in tablets, 3 per day. Each tablet was standardised to 0.9 mg total hypericin and equivalent to 1500 to 1800 mg of flowering tops. There was a steady improvement in his mood over 6 to 8 weeks and he felt much better and more positive about life. The patient was maintained at 2 tablets per day with continued benefit.

Insomnia

Generally patients seek phytotherapy for insomnia that has become a chronic problem. The DSM-IV additionally requires that with chronic primary insomnia the patient’s sleep disturbance disrupts his or her daily performance and quality of life.78 It can be difficult in practice to differentiate primary insomnia from possible secondary causes such as alcohol and medical problems. Hence, it is more practical to address all the issues that might be contributing to the insomnia, while prescribing herbs as if it was primary insomnia. This approach therefore requires a detailed and careful case history and appropriate counselling of the patient.

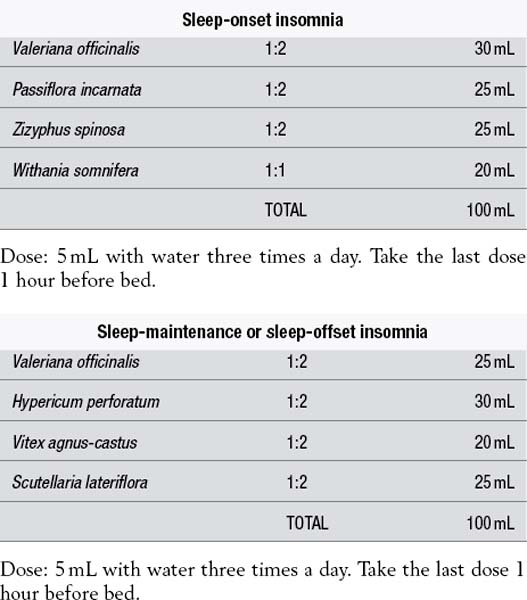

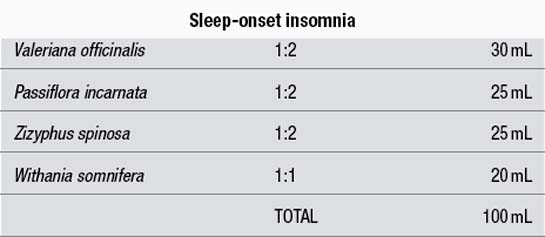

Insomnia, or inadequate sleep, can be categorised for phytotherapy according to the difficulties experienced by the patient. These include difficulty falling asleep (sleep-onset insomnia), awakening during the night with difficulty falling back to sleep (sleep-maintenance insomnia), early morning awakening (sleep-offset insomnia) and a sense of not having enough sleep (non-restorative sleep). Patients can report a combination of these.

Major causes of sleep-onset insomnia include anxiety, pain or discomfort, caffeine and alcohol. Sleep-maintenance insomnia can be linked to depression, sleep apnoea, fibromyalgia syndrome, nocturnal hypoglycaemia, pain or discomfort and alcohol. If restless legs syndrome is a cause of insomnia, this should be addressed separately (see later in this section). Any obvious causes of the insomnia (such as pain) should also be treated separately.

It is important to ensure that the patient sleeps in a darkened, noise-free environment in a comfortable bed. The use of stimulants should be reduced, especially coffee, tea, guarana and cola drinks. Alcohol intake should also be reduced. Unwinding at night can be important and a few drops of lavender oil added to an evening bath can help this process. Where the insomnia has been precipitated by anxiety or other psychological problems, appropriate counselling or phytotherapy should be recommended. The key herbs for insomnia to be considered will depend on the pattern of the insomnia:

• Anxiolytic and hypnotic herbs are the mainstay of treatment. These can be taken throughout the day to prevent a build-up of tension or mental excitability that might result in insomnia. An additional dose is then recommended around 1 hour before bed. If the insomnia is not severe, then the herbs can be taken as a single dose before bed. Key herbs include valerian, kava, Zizyphus, hops, lemon balm, Magnolia, lavender, passionflower, California poppy and chamomile. Best results with valerian come from continuous use for at least 2 weeks (see monograph).

• Antidepressant and nervine tonic herbs are indicated, especially if the insomnia is associated with fibromyalgia or is sleep-maintenance insomnia. These include St John’s wort, saffron, skullcap, damiana, Rhodiola and Schisandra.

• If the patient is debilitated and suffers from sleep-maintenance insomnia, then adrenal restorative herbs such as licorice or Rehmannia are also indicated. These herbs will additionally help to maintain blood sugar levels during the night.

• Tonic and adaptogenic herbs used throughout the day can help to break the vicious cycle of non-restorative sleep in stressed patients. The safest and best herb to use in this context is Withania, although a small amount of ginseng will not be too stimulating for most patients. Also use of those herbs taken just before bed can tonify (and thereby improve) the sleep of patients experiencing non-restorative sleep.

• If pain interferes with sleep then analgesic herbs for pain management are indicated. For example, willow bark is useful for pain associated with inflammation, whereas Corydalis, cramp bark, kava and wild yam will help to alleviate pain associated with smooth muscle cramping. (See also the treatments for restless legs syndrome and nocturnal myoclonus.)

Recent research with Vitex (chaste tree) and melatonin represents a promising new development in the herbal treatment of maintenance insomnia (see monograph).

Example liquid formulas

Dose: 5 mL with water three times a day. Take the last dose 1 hour before bed.

Dose: 5 mL with water three times a day. Take the last dose 1 hour before bed.

Case history

A male patient aged 47 complained of difficulty falling asleep some nights. He was prescribed kava tablets, 2 to 3 about 50 minutes before bed. Each tablet contained 200 mg of extract standardised to 60 mg of kava lactones and equivalent to about 1800 to 2000 mg of root. He found the tablets very effective, but did find that they caused early morning drowsiness on some, but not all, mornings after he used them.

Case history

A female patient, aged 59, suffered from fibromyalgia (which was treated with a herbal mixture taken during the day). However, a significant problem (typically associated with fibromyalgia) was her terrible insomnia. She claimed that some nights she only slept for about 1 hour. Valerian tablets and kava tablets were tried to no effect.

She was prescribed the following formula:

| Zizyphus spinosa | 1:2 | 30 mL |

| Scutellaria lateriflora | 1:2 | 25 mL |

| Lavandula officinalis | 1:2 | 20 mL |

| Corydalis ambigua | 1:2 | 25 mL |

| total | 100 mL |

Dose: 8 mL with water about 30 minutes before bed. Repeat a few hours later if still awake.

The above sleep mixture helped tremendously and, with the sleep improvement, her fibromyalgia also improved more rapidly.

Restless legs syndrome (and nocturnal myoclonus)

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) has been described as ‘the most common disorder you’ve never heard of’.83 It is an unusual sensation (paraesthesia) in the legs that typically occurs at bedtime and is a common cause of insomnia. The cause of RLS is not known. It is known to be associated with a number of medical conditions including iron deficiency, pregnancy and dialysis.

RLS is surprisingly common and plagues the sleep of many sufferers. Various estimates have ranged from 2% to 15% of the adult population, with the real number likely to be about 6%. It is more common in women.84 The older the person, the more likely he or she will suffer from restless legs. It is rare in young children, but for those older than 65 years around 10% to 28% are affected.

Lower iron levels in the brain affect dopamine metabolism, specifically inhibition of tyrosine hydroxylase needed for the synthesis of dopamine and requiring iron as a cofactor.85 In one study, 75% of patients with RLS had decreased iron stores. Iron concentrations in the blood drop by 50% to 60% at night. Ferritin concentrations of <50 ng/mL have been correlated with decreased sleep efficiency and increased leg movements in sleep in RLS. Oral supplementation of iron has resulted in significant clinical improvement in RLS. Some patients with RLS improve with folate supplementation, which is also involved in tyrosine hydroxylase production.84

Magnesium therapy (12.4 mmol/day=301 mg/day) has been shown to be beneficial.86 A placebo-controlled trial found that 800 mg/day Valerian root for 8 weeks improved RLS symptoms and daytime sleepiness.87 A recent pilot trial with Vitex (chaste tree) was also promising (see monograph). A number of lifestyle factors have been associated with RLS. These include heavy smoking, advanced age, obesity, hypertension, loud snoring, use of antidepressant drugs,83 diabetes and lack of exercise.88

Conventional medical treatment for RLS focuses on drugs for the nervous system, especially dopaminergic agents. Many of these drugs are quite powerful and dangerous and should be reserved for more severe cases.82 A study found that RLS was very common in people with varicose veins (22% incidence).89 After treatment for superficial varicose veins (sclerotherapy or vein stripping), 98% reported an immediate improvement in their restless legs.

When the blood is not circulating properly, the walls of the deeper veins can stretch, resulting in unpleasant sensations in the legs. The sluggish circulation can cause red blood cell aggregation that can further add to the paraesthesia and restless legs. Consistent with this, the condition is much more common during pregnancy.82 One survey of 500 women found that 19% reported RLS during pregnancy, that 7% described their symptoms as ‘severe’ and that the condition abated in 96% of affected women within 1 month of giving birth.82

Key herbs to consider for RLS are:

• anxiolytic and hypnotic herbs such as valerian, kava (especially), skullcap and passionflower to alleviate the nervous system imbalance that is part of RLS

• many of the factors involved in RLS (smoking, pregnancy, obesity, age, diabetes) all point to an involvement of the circulation. Hence venotonic herbs such as horsechestnut and butcher’s broom and herbs that enhance circulation such as Ginkgo have a key (but often neglected) role to play

Case history

A female patient aged 61 complained of sleep-onset insomnia and sleep latency largely brought about by restless legs at night. There was a history of anxiety and poor venous circulation. She was prescribed tablets (2 per day) containing Aesculus hippocastanum (horsechestnut) 1.2 g, Ginkgo biloba (Ginkgo) 1.5 g and Ruscus aculeatus (butcher’s broom) 800 mg and a magnesium supplement. Kava tablets (providing 120 to 180 mg kava lactones per day) were also to be taken as required.

This patient was successfully treated for about 2 years as above and then found that the treatment could be stopped for many months without problem. The treatment was started again if symptoms returned. This on and off approach was followed for 3 years.

Chronic tension headache

Chronic tension-type headache (TTH) is a neurological disorder characterised by frequent attacks of mild to moderate headache with few other symptoms.90 The headaches are typically bilateral, have a pressing (non-pulsatile) quality and are not aggravated by routine physical activity. They are not characterised by nausea or vomiting and no other causes are found. TTH affects up to 78% of the general population and 3% suffer from the chronic form.91

Peripheral factors are implicated in episodic TTH, whereas central factors probably underlie chronic TTH. Activation of hyperexcitable peripheral afferent neurons from head and neck muscles is the most likely explanation for infrequent headaches.90 Muscle and psychological tension are associated with and can aggravate TTH, but are not believed to be the cause. Abnormalities in central pain processing and a generalised increase in pain sensitivity are present in some patients with chronic TTH.90,92

The treatment of a single episode of tension headache is rarely an issue for a consultation for herbal treatment. The commonly encountered clinical situation is recurrent or chronic TTH, hence the approach to treatment described below is more aimed at the prevention of headaches, but many of the herbs below will also alleviate tension headache pain. Herbs with mild analgesic properties still have a role in this context because they generally also possess some relaxing or anxiolytic activity.

Aspects of herbal treatment that should be considered:

• If the headaches are related to trigger foods, or there are signs of problems with digestion, then bitter herbs to improve upper digestive and choleretic herbs to improve liver function should be included.

• Anxiolytic and nervine tonic herbs should be prescribed if appropriate, especially those which have some analgesic activity such as Corydalis and kava.

• Spasmolytic herbs, particularly those with an effect on the circulation can help to prevent tension headaches. These include wild yam, hawthorn, cramp bark and chamomile.

• Analgesic herbs include willow bark, California poppy and Corydalis. As well as its role in migraine, feverfew is a useful anti-inflammatory herb in TTH.

• If the headaches have a relationship with the menstrual cycle, then hormonal regulating herbs may be valuable, for example chaste tree if the headaches occur premenstrually.

• If eye strain is a factor then higher doses of bilberry (equivalent to at least 80 mg of anthocyanins per day) are indicated.

• In elderly people, cerebral ischaemia may contribute to headaches and can be treated with Ginkgo if there is evidence of its presence.

• Topical application of peppermint oil to the temples has been shown to relieve headache pain in clinical trials (see monograph).

• If the above approach does not give results then localised traction or compression of veins or nerves may be a cause, and anti-inflammatory and antioedema herbs such as horsechestnut and butcher’s broom should be tried in conjunction with St John’s wort (similar to the approach described next for trigeminal neuralgia).

• For headaches due to sinusitis, treatment should focus on this condition. An analgesic herb such as willow bark could also be recommended.

Example liquid formula

| Corydalis ambigua | 1:2 | 25 mL |

| Viburnum opulus | 1:2 | 25 mL |

| Crataegus monogyna leaf | 1:2 | 30 mL |

| Matricaria recutita (high in bisabolol) | 1:2 | 20 mL |

| total | 100 mL |

Dose: 8 mL with water twice a day.

Case history

A male patient, aged 74, complained of headaches and fatigue. He had experienced about one headache per week on and off for years. He had some sinus problems, with post-nasal drip at night and his nose could be blocked at times. He used to have migraines and his headaches were worse with stress. He worked long hours and was anxious and worried.

He was prescribed the following herbs:

| Euphrasia officinalis | 1:2 | 20 mL |

| Viburnum opulus | 1:2 | 15 mL |

| Tanacetum parthenium | 1:5 | 10 mL |

| Matricaria recutita | 1:2 | 15 mL |

| Corydalis ambigua | 1:2 | 20 mL |

| Crataegus monogyna leaf | 1:2 | 20 mL |

| total | 100 mL |

Dose: 5 mL with water three times a day.

For the fatigue he was also prescribed 2 tablets per day, each containing Withania root 600 mg and ginseng main root 125 mg. The eyebright was included in the treatment because of the possible association of the headaches with his sinus condition. After 8 weeks on the herbal treatment he was relatively free from headaches.

Trigeminal neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia, also known as tic douloureux, is a frequent cause of facial pain that involves the trigeminal nerve and occurs almost exclusively in middle-aged or elderly people. The pain is severe and fleeting and may be so severe that the patient winces (hence the term tic). Pain attacks tend to occur in clusters that can go on for several weeks.93

The pathogenesis of trigeminal neuralgia is speculated to be an ephaptic conduction caused by segmental demyelination and artificial synapse formation (in other words the trigeminal nerve becomes cross-wired due to demyelination). The cause of the demyelination might be multiple sclerosis, vascular degeneration or ageing. However, one recent review suggested that the most common aetiology is vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve root entry zone that leads to a focal demyelination.94 The blood vessels involved are said to be aberrant or tortuous.92 Studies have demonstrated proximity of the nerve root to such vessels, usually the superior cerebellar artery.

Under a relatively new classification from the International Headache Society, for the diagnosis of classical trigeminal neuralgia no cause of symptoms other than vascular compression can be found. In contrast, symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia has the same clinical picture, but an underlying cause such as multiple sclerosis, amyloid filtration, small brain infarcts or bony compression is identified.92

Relevant herbs to consider include the following:

• A key herb is St John’s wort, which is traditionally prescribed for any neuralgia related to nerve irritation or compression.

• The health of large blood vessels and the microcirculation can be improved with grape seed and pine bark extracts and bilberry, Ginkgo, garlic, gotu kola and hawthorn.

• Any compression caused by oedema associated with inflammation or tortuous vessels can be treated with horsechestnut. The venous-toning effect of this herb may also be of value.

• Anti-inflammatory herbs could be tried, such as Boswellia and turmeric.

• Analgesic herbs such as Corydalis or willow bark can be prescribed for the painful episodes.

• Effects from demyelination can be somewhat improved by ensuring adequate intake of essential fatty acids (for example evening primrose oil, which is also anti-inflammatory) and improving the microvasculature (see above).

• A published case history described the successful use of consumption of 30 to 60 mL/day of Aloe vera juice for 3 months. The patient’s pain diminished significantly within 2 weeks of initiating therapy. When she stopped the Aloe juice her pain returned and it went within a few days of starting it again.95

Case history

A male patient, aged 77, presented with trigeminal neuralgia on the right side of his face. He had had the condition for about 9 years and it was first diagnosed as a dental problem. His episodes of attacks numbered 2 to 3 per year and each episode lasted 3 weeks to 3 months. While he was experiencing attacks he found it difficult to shave or wash his face. He was told by a specialist that a blood vessel was impinging on the trigeminal nerve (he had a history of atherosclerosis of the carotid arteries and angina pectoris). He was prescribed carbamazepine for the trigeminal neuralgia, but was concerned that this medication made him feel sluggish. His case history revealed that he suffered from hayfever with bouts of sneezing and he drank an enormous amount of tea each day (which he was advised to reduce).

He was prescribed the following herbal treatments:

• Grape seed extract tablets 100 mg/day

• Tablets (3 per day) containing the following herbs:

| Scutellaria baicalensis | 1:2 | 30 mL |

| Hypericum perforatum | 1:2 | 30 mL |

| Crataegus monogyna leaf | 1:2 | 30 mL |

| Ginkgo biloba (standardised extract) | 2:1 | 10 mL |

| total | 100 mL |

Dose: 5 mL with water twice a day.

(The Ginkgo in the liquid supplemented the amount in the tablets containing horsechestnut and butcher’s broom.) Over the ensuing months the intensity and frequency of the neuralgia abated and after 6 months he was free of pain and not taking carbamazepine. Continued treatment maintained the freedom from neuralgia. He was also sneezing less.

Rationale

Given the association with circulation, grape seed extract and Ginkgo were prescribed to boost the integrity of the microvascular circulation, hawthorn for the arteries and horsechestnut and butcher’s broom for any pressure on the nerve associated with oedema or venous congestion.

Baical skullcap and grape seed were to help reduce the sneezing and St John’s wort was given for the irritated trigeminal nerve.

Migraine

Results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Study indicate that the cumulative lifetime incidence of migraine in the USA is 43% for women and 18% for men. This frequency is likely to be reflected in most Western countries and, given that the diagnostic criteria used were relatively stringent, the incidence may be even greater.96

A migraine is a complex brain event that can produce a wide array of neurological and systemic symptoms. Although the term migraine is derived from the word hemicrania, meaning one side of the head, the pain is not necessarily one-sided. Symptoms include extreme and prolonged head pain, photophobia, nausea and vomiting. Sometimes the migraine is preceded by sensory (especially visual) or motor symptoms (the aura). More commonly there is no aura.

The vascular theory of migraine was proposed by Wolff and others in the 1930s. It attributes migraine to an initial intracranial vasoconstriction (which accounts for the aura) followed by an extracranial vasodilation (the headache). However, this theory was not consistent with later experimental observations.

There has been further movement away from the concept of migraine as a primarily vascular disorder.96 Although intracranial vasodilation is an appealingly simple explanation for migraine pain, this hypothesis has never been capable of explaining the wide range of symptoms that may precede, accompany, or follow the pain. Multiple imaging studies have now confirmed that vasodilation is not required for migraine headache. In fact cortical hypoperfusion during the headache is more characteristic.

A corollary of the vascular hypothesis of migraine is the concept that vasoconstriction is a primary mechanism by which caffeine, ergotamines and triptans exert their therapeutic effect. But experimental studies do not support this understanding and suggest that the mode of action of each drug class is complex and distinct.96 However, the vascular hypothesis still has its supporters as well as detractors.97

Migraine is currently hypothesised by some researchers as an episodic disorder of brain excitability, akin to epilepsy and episodic movement disorders. Waves of altered brain function, such as cortical spreading depression could be responsible for translating changes in cellular excitability into a migraine attack.96 This suggests a role for sedative and antiepileptic herbs.

Another suggestion is that migraine is an episode of local sterile meningeal inflammation and the subsequent activation of trigeminal neurons that supply the intracranial meninges and related large blood vessels.98 Meningeal mast cells could be involved here as triggers, suggesting a role of Scutellaria baicalensis, given the neurological and mast cell activities of its flavonoids.

Epidemiological studies suggest that migraine is associated with disorders of the cerebral, coronary, retinal, dermal and peripheral vasculature. There is evidence that migraine is associated with vascular endothelial dysfunction and impaired vascular reactivity, both as a cause and a consequence.99 This suggests a role for microvascular herbs and could explain the role of feverfew in migraine, including this herb’s possible effects on platelet function (see the feverfew monograph).

Migraine is a potentially progressive disorder, and progression of episodic migraine to chronic migraine (migraine chronification) is associated with a range of co-morbidities and risk factors, that could represent either cause or effect. Hypertension is one such co-morbidity,100 others include obesity, excessive use of medications, caffeine overuse, stressful life events, depression, sleep disorders, cutaneous allodynia,101 temporomandibular disorders,102 white matter lesions in the brain,103 cardiac and vascular problems, psychiatric disorders,104 head injury, pro-inflammatory states and prothrombotic states.105

The higher frequency of migraine in women has already been noted, and menstrual migraine, which occurs before or during menstruation, is believed to be associated with the fall of oestrogen.106 In other women, oral contraceptive use can trigger migraines.105 At menopause, migraine can regress, worsen or remain unchanged.105

Other factors linked to migraine development or migraine attacks include prolonged stress,107,108 and trigger foods such as cheese, coffee, chocolate or citrus fruits. Alcohol drinks, especially red wine, can also act as a trigger. About 40% of migraine sufferers tested positive for Helicobacter pylori, and eradicating this organism resulted in a significant clinical improvement.109

As well as trigger foods it has been suggested that other food allergies could also be a factor in migraine headaches. Commonly implicated foods include cow’s milk products, wheat and eggs.110 Poor body alignment and the benefits of spinal manipulation are particularly relevant to this condition.

In general, patients seeking phytotherapy for migraine will be sufferers of chronic migraine. Hence therapy is best aimed at preventing attacks, although a separate formula to abort attacks if taken early can be prescribed. This abortive treatment could include herbs such as feverfew, willow bark, ginger and Corydalis, all in relatively high doses.

Considerations for preventative herbal treatment include selection from the following:

• Anxiolytic and nervine tonic herbs are used for the effects of stress, especially those having some analgesic activity such as Corydalis. St John’s wort may be particularly valuable, as will herbs with some antiepileptic properties such as kava, Bacopa, Withania and valerian.

• Feverfew works well as a migraine prophylactic, but it must contain good levels of parthenolide. It takes about 4 to 6 months to fully work (see feverfew monograph). Since its primary effect may be on platelets, its role may be supported by antiplatelet herbs such as ginger and turmeric.

• If the migraines are related to trigger foods or there are signs of problems with digestion, then herbs to improve upper digestive and liver function should be included. Phytotherapy places an emphasis on the relationship between migraine headaches and liver function. It is good practice to include a liver herb in a migraine preventative formula, be it a choleretic herb such as globe artichoke or ones that aid hepatic detoxification such as turmeric or Schisandra. In France, this liver connection is acknowledged by phytotherapists, as evidenced by a study of migraine treated by the liver herb Fumaria officinalis (fumitory).111Helicobacter pylori can be treated with bitters, garlic, sage, thyme, Nigella and golden seal (see also pp. 321–322).

• Menstrual migraine should be treated with herbs with oestrogenic effects such as shatavari, wild yam and Tribulus. Premenstrual migraine may be alleviated by prescribing chaste tree.

• Ginkgo should be included in a preventative formula, given that cortical hypoperfusion is associated with migraine. The anti-PAF activity of Ginkgo (PAF is platelet activating factor) may also be an advantage.

• Spasmolytic herbs, particularly those with an effect on the circulation, can help to prevent a migraine. These include hawthorn, cramp bark and chamomile. The spasmolytic herb butterbur is used in Europe for migraine prophylaxis. (Caution: butterbur contains toxic pyrrolizidine alkaloids, but these compounds have been removed from products permitted for sale in Europe.)

• Given that a pro-inflammatory cascade might be involved in the aetiology of migraine, anti-inflammatory herbs such as Boswellia, turmeric and ginger could be of value as preventive agents.

• Herbs for microvasculature and promoting endothelial health could be of value. These include garlic, bilberry, pine bark and grape seed extracts, Ginkgo, green tea, turmeric, and Polygonum cuspidatum (as a source of resveratrol).

Example liquid formula

| Tanacetum parthenium | 1:5 | 20 mL |

| Hypericum perforatum or Bacopa monniera | 1:2 | 30 mL |

| Schisandra chinensis | 1:2 | 25 mL |

| Zingiber officinale | 1:2 | 10 mL |

| Viburnum opulus | 1:2 | 20 mL |

| total | 105 mL |

Dose: 8 mL with water twice a day.

Case history

A female patient aged 43 suffered from about two severe migraines a month. There did not appear to be any association with trigger foods and they tended to occur premenstrually. She was prescribed the following treatments:

• Feverfew tablets 150 mg standardised to contain 900 μg parthenolide, 2 tablets per day

• Three tablets per day of an anti-inflammatory formula containing Boswellia extract 200 mg equivalent to dry gum resin 2400 mg containing boswellic acids 135 mg, celery seed oil equivalent to dry seed 3000 mg, and ginger rhizome 300 mg

Over a period of about 4 to 6 months the migraines reduced substantially in frequency and severity. She found that conventional analgesics such as aspirin could better abort or allay an attack than previously (this is a common finding with feverfew therapy).

Enhancing cognition

Although not a health issue, there is considerable interest in herbs that may be able to effect cognition enhancement, for example among students studying for exams or older people whose memories are weakening. In addition, these herbs form a central part of the treatment of more serious conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease.

On current evidence, Ginkgo has been shown to improve cognitive function, although there have been some negative findings (see Ginkgo monograph). In particular, the combination of Ginkgo and ginseng seems to be particularly powerful at improving cognition in both acute and long-term studies (see the ginseng monograph).

The Ayurvedic herb Bacopa monniera, also known as brahmi in India, has a strong traditional reputation for improving cognitive function and intelligence.112 Several clinical trials have found that various Bacopa extracts (typically at around 300 mg/day) improved cognitive function in healthy volunteers, usually when given over 90 days.113–115 Features of some of these trials included effects being maximal at 90 days and Bacopa decreasing the rate of forgetting of new information. A short-term trial (2 hours) on Bacopa showed no benefit.113

In a 12-week randomised, double blind trial conducted in the USA, the effect of 300 mg/day of Bacopa on cognitive function was investigated in healthy elderly volunteers. The main outcome was measured by the delayed recall score from the AVLT (Auditory Verbal Learning Test) word memory task. Also measured was the Stroop Task which assesses the ability to ignore irrelevant information. The following results were obtained:116

• Bacopa significantly enhanced AVLT delayed word recall memory scores

• Stroop results were similarly significant, with the Bacopa group improving and the placebo group unchanged

• Depression and anxiety scores and heart rate significantly decreased over time for the Bacopa group, compared to an increase in the placebo group

• No effects were found on the DAT (Divided Attention Task).

A team of British and Australian scientists, including Professor Andrew Scholey now at Swinburne University, have undertaken a series of investigations on sage (Salvia officinalis) because of its traditional reputation as a tonic for the nervous system and memory. For example, the 16th century English herbalist John Gerard wrote about sage: ‘It is singularly good for the head and brain and quickeneth the nerves and memory’. The investigators used a randomised, placebo-controlled, double blind, crossover design to investigate the effects of a single dose of sage in healthy older volunteers over a 6-hour period.117 Compared with the placebo phase (which generally exhibited the characteristic decline in performance over the 6-hour test period), the 333 mg extract dose of sage caused a highly significant enhancement of secondary memory at all testing times. Secondary memory is longer term memory where, in this case, recently supplied information is processed. There were also significant improvements in accuracy of attention following this dose, but not for the other doses. The extract used in the study was also shown to inhibit cholinesterase in test tube experiments. The authors concluded that the overall pattern of results was consistent with a benefit to pathways involved in efficient processing of information and/or consolidation of memory, rather than enhanced efficiencies in retrieval or working memory. The optimum sage dosage of 333 mg (about 2.5 g of herb) improved secondary memory by about 30 units. The decline with age for the healthy group tested (compared to healthy 18 to 25 year olds) was around 40 units. Hence the benefits seen in the present study reflect a substantial temporary reversal of the deterioration in secondary memory that typically occurs with about 50 years of normal ageing.

Other herbs demonstrated to improve cognitive function include gotu kola (see monograph), Schisandra and Rhodiola. In two sets of experiments, young (21 to 24 year old) telegraph-operators were asked to transmit Morse code at maximum speed for a period of 5 minutes.118,119 Following treatment with a single dose of Schisandra extract (3 g herb) the test was repeated. The error frequency was within the range 84% to 103%, whilst that of the control group (treated with a placebo of glucose or 70% ethanol) was 130%. It was concluded that Schisandra prevented or reduced exhaustion-related errors. By using a test method involving the correction of texts in which fatigue affected the accuracy but not the speed of work120 it was demonstrated that 38 (65%) of a group of 59 students treated with Schisandra showed an improvement in performance. Of these, seven presented an increase in the amount of work performed, 14 exhibited an enhancement in the quality of correction, and 17 showed improvements with respect to both of these.

A combination of Rhodiola, Siberian ginseng and Schisandra, used either in single or repeated doses, significantly increased the mental working capacity of healthy volunteers (computer operators on night duty).121 A relatively low dose of Rhodiola extract at 170 mg/day for 2 weeks improved five different tests of cognitive function in a double blind, placebo-controlled trial in 56 young, healthy doctors on night duty.122

Cognition-enhancing herbs can also be of value in children, including those suffering attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and Bacopa is a good example of this. BR-16A is an Ayurvedic herbal formulation containing Bacopa as the main ingredient. It was evaluated for its efficacy in an open label trial in 25 children aged between 4 and 14 years having hyperkinetic behavioural problems. The duration of the problem ranged from 6 months to 3 years. Fifteen children were mentally disadvantaged and amongst them 10 had a history of brain damage. The herbal syrup brought about ‘marked improvement’ in five children as judged by both parents and doctors. No side effects were noted.123

In terms of controlled trials in ADHD, two have been conducted: one with BR-16A and the other using Bacopa alone. A randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled trial was undertaken to evaluate the efficacy of BR-16A in school-going children with ADHD. A total of 195 children were screened, out of which 60 satisfied the medical criteria for ADHD. Among those enrolled in the study, 30 received herbal treatment and 30 received placebo. An assessment of academic functioning along with psychological tests was done before and after the treatment. Statistical analysis was carried out in only 50 children and showed improvement in these tests in the herbal group compared with the placebo group. However, none of these differences achieved statistical significance because of the low number of trial participants.124

The study of Bacopa in ADHD was a small pilot study only published in abstract form. In this trial, a double blind, randomised, placebo-controlled design was employed. A total of 36 children were involved. Of these, 19 received Bacopa extract 100 mg/day for 12 weeks and 17 were given placebo. The active herbal treatment was followed by a 4-week placebo administration, making the total duration of the trial 16 weeks in both groups. One child in the Bacopa group and six in the placebo group dropped out. The mean ages were 8.3 years and 9.3 years in the Bacopa and placebo groups respectively. The children were evaluated on a battery of tests including mental control, sentence repetition, logical memory and word recall. Evaluation was undertaken before, during and at the end of the study. Data analysis revealed a significant improvement with sentence repetition, logical memory and learning following 12 weeks’ administration of Bacopa. This improvement was maintained at 16 weeks. During the clinical trial Bacopa exhibited excellent tolerability and no treatment-related adverse effects were reported.125

Pycnogenol, a proprietary, standardised extract of French maritime pine bark (Pinus pinaster) has shown promising results in ADHD and the clinical trial data in children is more robust than for Bacopa. Initial positive case reports stimulated the interest to study this extract further.126–128 However, a double blind, placebo-controlled comparative study in adults with ADHD failed to yield significant results.129 No significant differences were found between placebo, the drug methylphenidate and pine bark extract. However, the sensitivity of this study can be questioned since it also found no activity for the reference drug.

A pilot study found a significant improvement in ADHD for the pine bark extract in children at 1 mg/kg/day.130 This then led to a double blind, placebo-controlled study in 61 children, using the same dose over 4 weeks.131 Patients were examined at start of trial, 1 month after treatment and 1 month after the end of treatment period by standard questionnaires: CAP (Child Attention Problems) Teacher Rating Scale, Conner’s Teacher Rating Scale (CTRS), the Conner’s Parent Rating Scale (CPRS) and a modified Wechsler Intelligence Scale for children. Results showed that 1 month of the pine bark extract caused a significant reduction of hyperactivity and improved the attention, coordination and concentration of children with ADHD. No positive effects were found in the placebo group. A relapse of symptoms was noted 1 month after termination of treatment.

Example liquid formulas

For stress-associated memory impairment:

| Glycyrrhiza glabra | 1:1 | 20 mL |

| Rhodiola rosea (standardised extract) | 2:1 | 25 mL |

| Ginkgo biloba (standardised extract) | 2:1 | 40 mL |

| Panax ginseng (standardised extract) | 1:2 | 20 mL |

| total | 105 mL |

Dose: 8 mL with water twice a day.

For acutely improving short-term memory and cognitive function (the student or speaker’s friend):

| Ginkgo biloba (standardised extract) | 2:1 | 60 mL |

| Panax ginseng (standardised extract) | 1:2 | 40 mL |

| total | 100 mL |

Dose: 8 mL twice within a 1 hour period about 1 to 2 hours before an exam or lecture.

For age-associated cognitive decline:

| Ginkgo biloba (standardised extract) | 2:1 | 35 mL |

| Salvia fruticosa | 1:2 | 30 mL |

| Panax ginseng (standardised extract) | 1:2 | 15 mL |

| Rhodiola rosea (standardised extract) | 2:1 | 25 mL |

| total | 105 mL |

Dose: 8 mL with water twice a day.

Combine with tablets containing an extract of Bacopa capable of providing the equivalent of at least 10 g of herb per day (100 mg bacosides).

Case history

A student studying for university exams requested a formula to improve performance in the exam and concentration and memory while studying. She was prescribed the following formula:

| Ginkgo biloba (standardised extract) | 2:1 | 20 mL |

| Eleutherococcus senticosus | 1:2 | 30 mL |

| Schisandra chinensis | 1:2 | 25 mL |

| Bacopa monniera | 1:2 | 25 mL |

| total | 100 mL |

Dose: 8 mL with water twice a day. (Note: The Siberian ginseng was prescribed for the stressful effects of studying as well as its effects on performance.)

The student reported improved concentration and memory and less fatigue while studying. She passed her exams.