Esthetics in Tooth Display and Smile Design

Bjørn U. Zachrisson

The orthodontic profession has always been in pursuit of the ideal dentition. At present, we are on the threshold of a paradigm shift that apparently will change the fundamental conceptual basis of orthodontics and the traditional emphasis in diagnosis and treatment planning.1,2 The former emphasis on dental and skeletal components is still valid but greater attention than before is now required to the soft tissue aspects of orthodontics. In an effort to create natural esthetics, the orthodontist must give careful consideration to the patient in his or her entirety. Individual attributes of a tooth or segment of teeth may represent only part of the story, because teeth do not exist individually and separate from the patient to whom they belong. Combinations of tooth positions can create an effect that is greater than, equal to, or less than the sum of the parts.3 The discipline of esthetics in orthodontics can be broken down into at least four parts: microesthetics (the elements that make teeth look like teeth), gingival esthetics, macroesthetics (the principles that apply when groupings of individual teeth are considered), and facial esthetics.3 This chapter will focus on the principles of macroesthetics and facial esthetics in orthodontics and how to apply them clinically. The dynamic relationship between the teeth and the surrounding soft tissues during and after orthodontic corrections and the patient's facial characteristics will be emphasized. The display (amount and shape of crown structure that shows in various views and lip positions) will be related to age, sex, and facial characteristics. The purpose is to provide guidelines for orthodontists on how to analyze esthetic factors by viewing the patient from the front and to discuss some new concepts on how to achieve the desirable characteristics of tooth display in the vertical and transverse dimensions during normal social interaction.

Evaluating Esthetics in the Dentist's Chair

Esthetics, which is derived from the Greek word for “perception,” deals with beauty and the beautiful. It may be divided into two dimensions: objective (admirable) and subjective (enjoyable) beauty.4 Objective beauty implies that the object possesses properties that make it unmistakably praiseworthy. Subjective beauty is value-laden and is related to the tastes of the person contemplating it. Contemporary techniques in orthodontics should lend objective esthetics to the entire orofacial complex, involving unity, form, structure, balance, color, function, and display of the dentition. In addition, the creation of subjective beauty according to an individual orthodontist's preferences may enhance the cosmetic value of the treatment rendered to each patient.

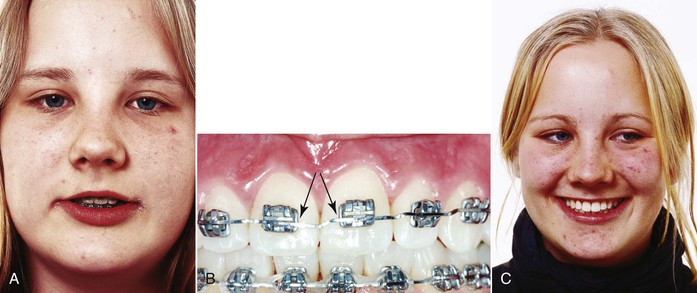

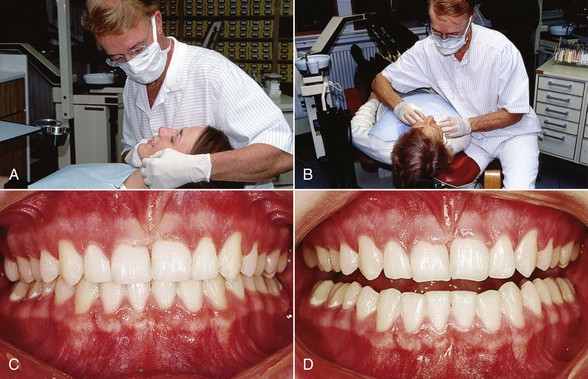

In discussing the principles of visual perception and its clinical application to dentofacial esthetics, Lombardi5 remarked that detailed esthetic judgments can be made only by viewing patients from the front, in conversation, and observing facial expressions and smiling. The traditional dentist's view from above and behind the patient is skewed, differing markedly from the “true” perception of the patient in a mirror or by other persons during normal social interaction. For example, it is not possible to gain adequate information on such details as midline alignment (maxillary and mandibular relative to facial) and right-left symmetry of canine and premolar crown torque (Fig. 3-1, A) unless the patient is observed directly from the front (Fig. 3-1, B). A direct “eye-to-eye” view of the dentition can, in fact, be obtained when the patient is sitting in the dental chair6; the trick is to move the patient's head to the side of the headrest (see Fig. 3-1, B). With this method it is possible to analyze important esthetic factors during the treatment (Fig. 3-1, C and D), such as:

• Crown lengths of the upper and lower incisors

• Incisal edge contours (before and after recontouring)

• Position and symmetry of gingival margin levels on the upper and lower anterior teeth

• Axial inclinations of all anterior teeth

• Midlines (maxillary to mandibular and facial)

• Connector areas (the zone in which two adjacent teeth appear to touch)

• Symmetry and degree of crown torque of the canines and premolars

Figure 3-1 A, Unsuitable position for evaluating esthetics during treatment. Moving the patient's head to the side of the headrest (B) allows direct frontal view of dentition (C) and a realistic impression of esthetic features. D, The incisal edge contours can be examined on slight mouth opening.

It is important for a successful outcome that the clinician has learned to look at all of these aspects and has the ability to make the necessary corrections while the fixed appliances are still on, because “you can only change what you see.”7 After carefully studying the patient's dentition, the orthodontist can make the required finishing archwire bends and perform any other esthetic procedures needed. For analysis of tooth display when speaking and smiling and viewing the buccal corridors on smiling, a better impression is obtained when the patient is sitting up or standing in front of the dentist.5,6

Standards of Normality

It is useful for esthetic oral rehabilitations to describe some average desirable characteristic features of smiles. These normative standards may serve as a guideline for enhancement of esthetics for the anterior component of the dentition.

Smile Type: Incisor and Gingival Display

Lip coverage of the maxillary incisors in full smiles is generally distinguished into three types: low, average, and high smiles.8 The most frequent type8,9 (found in about 70% of the young adult population) is the average smile that reveals 75% to 100% of the upper incisors. The low smile displays less than 75% of the maxillary incisors in a full smile and is found in about 20% of the population, whereas the high smile reveals the complete cervicoincisal length of the upper incisors and a contiguous band of gingiva and occurs in about 10% of the U.S. population.8 A fourth type of lip line height may be defined as a “gummy” smile, which occurs when patients show more than 4-mm of gingiva on smiling (discussed later in the chapter).10,11

Upper lip coverage will always increase with age and therefore the percentage of high smiles may be greater among younger age groups12,13 and smaller among older adults.9,14 There is also a sexual dimorphism in that low smile lines are predominantly a male characteristic and high smiles are predominantly a female characteristic.8

It is noteworthy that some marginal gingival display in smiling is not as objectionable to laypersons as orthodontists may imagine.10,13 We should therefore look on a moderately high smile type as an acceptable anatomic variation well within the usual range of lip-tooth-jaw relationships, especially among women.12,13

Smile Arc15,16 (Smile Curve)

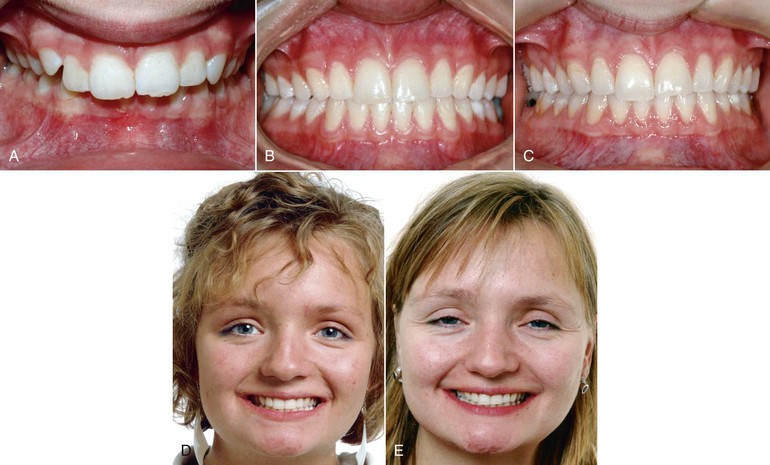

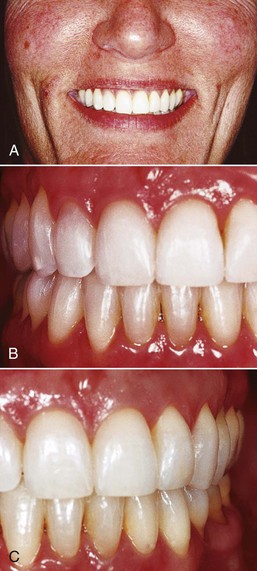

The relationship of the maxillary incisal curve to the inner contour of the lower lip can be divided into three types: parallel, straight, and reverse. In a survey of young adults in the Los Angeles area, Tjan et al.8 found that a great majority (85%) had a maxillary incisal smile curve parallel to the inner contour of the lower lip, 14% showed a straight rather than a curved line, and only 1% had a reverse smile curve. Since parallelism is the normal finding in untreated persons, it is an optimal goal for objective beauty in esthetic oral rehabilitations,17,18 including orthodontic (Figs. 3-2 and 3-3) and orthodontic-prosthetic treatments (Fig. 3-4). A straight or reverse smile curve may contribute to a less attractive facial appearance.5,17 The reverse curve is frequently associated with marked abrasive wear of the upper incisors.

Figure 3-2 A and B, Esthetic smile curve (arc) with parallelism between maxillary teeth and inner contour of lower lip in four-premolar extraction case. Upright canine and premolar crowns contribute to fullness of smile.

Figure 3-3 A–D, Improvement in parallelism between maxillary anterior tooth curve and lower lip contour with orthodontic treatment in adult female bimaxillary crowding case. Cant of maxillary central incisor midline is corrected.

Figure 3-4 A–D, Orthodontic-prosthetic interdisciplinary approach to improve parallelism between maxillary incisor curve and lower lip contour in adult female Class II, Division 2 malocclusion with worn central incisors. Four porcelain laminate veneers (courtesy Dr. S. Toreskog, Göteborg, Sweden) were used to restore and elongate the maxillary incisors.

Number of Teeth Displayed in the Smile

The California survey8 also revealed that in a typical or average smile in young adults, the six maxillary anterior teeth and the first or second premolars are displayed. The number of teeth displayed in the full smiles of 454 students was six anteriors only, 7%; six anteriors and first premolars, 48.5%; six anteriors and first and second premolars, 40.5%; and six anteriors, first and second premolars, and first molars, 4%.

Vertical Position of the Incisors

Normal Age Changes in Lip-Incisor Relationship

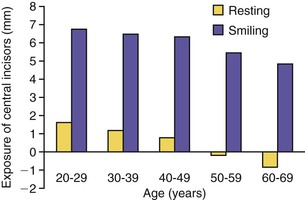

Progressive changes with age on upper and lower lip positions are caused by the effects of gravity. Some normative studies on the optimal vertical incisor positions in the faces of persons in different age groups are available. Peck et al.13 showed that the normal display of maxillary incisors with relaxed lips at 15 years of age was 4.7-mm (standard deviation [SD] 2.0-mm) for boys and 5.3-mm (SD 1.8-mm) for girls. The sexual dimorphism is evident at all ages. For adults, Vig and Brundo14 have provided normative mean values for different age groups (Table 3-1). Dong et al.19 compared the age changes in maxillary and mandibular incisor display at rest and when smiling (Fig. 3-5) and confirmed the observations that the age changes with relaxed lips were dramatic (Fig. 3-6). Mandibular incisor display shows a corresponding increase with age. The amount of mandibular incisor display after age 60 is approximately equal to the amount of maxillary incisor display before age 30 (see Fig. 3-5 and Fig. 3-6, D).

TABLE 3-1

Maxillary and Mandibular Incisor Display with Lips Gently Parted (in mm)

| Age Group (Years) | Maxillary Central Incisor | Mandibular Central Incisor |

| Up to 30 | 3.5 | 0.5 |

| 30–40 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| 40–50 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| 50–60 | 0.5 | 2.5 |

| Over 60 | 0.0 | 3.0 |

Modified from Vig RG, Brundo GC. The kinetics of anterior tooth display. J Prosthet Dent. 1978;39:502–504.

Figure 3-5 Comparison of maxillary incisor display by age with lips at rest and on smiling. (Reproduced with permission from Dong JK, Cho HW, Oh SC. The esthetics of the smile: a review of some recent studies. Int J Prosthodont. 1999;12:9–19.)

Figure 3-6 Age changes in vertical incisor display with relaxed lips, demonstrated by female patients aged 25 years (A and C) and 65 years (B and D). Note that the younger woman shows only maxillary incisors, whereas the older woman shows only mandibular incisors.

There is a close correlation between the incisor exposure at rest and during normal speech.20,21 The tooth display in speaking may be every bit as important as the tooth display in smiling to express personality and age. The most important information related to esthetics in treatment planning is obtained when the patient is observed during normal conversation. The tooth display on smiling will not provide the same information since when a person is smiling, the upper lip is raised actively by three different muscle groups.22 For this reason, nearly everyone, irrespective of age, will display the maxillary incisors nicely in the full smile, even if only the mandibular incisors are visible during their speech. In other words, the age changes in incisor display are much more pronounced and apparent with the lips relaxed and when the patient is speaking than when he or she is smiling (Fig. 3-7).15

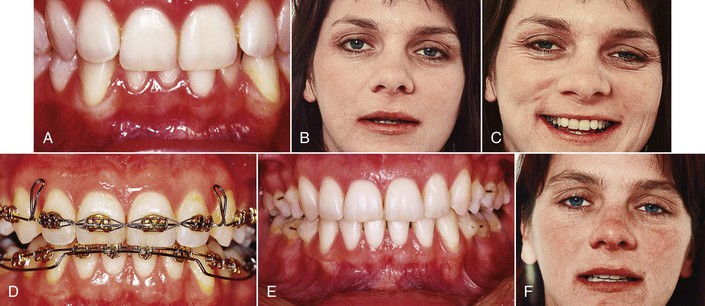

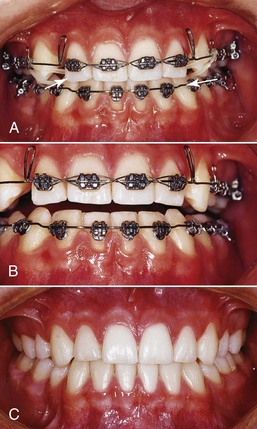

Figure 3-7 Deep anterior overbite in a 30-year-old female patient before (A–C), during (D), and after (E and F) orthodontic treatment. The initial maxillary incisor display with lips at rest (B) corresponds to a much older person. For this reason, the maxillary central incisors were extruded with step-down bends in the archwire and the mandibular incisors were intruded using an overlay base arch (D). Final result shows overbite correction (E) and a maxillary incisor display more relevant to the patient's age (F).

The sagging of the perioral soft tissue is partly due to the natural flattening, stretching, and decreasing elasticity of the skin.23 The upper lip becomes longer and hides more and more of the maxillary incisors, while the drooping of the lower lip gradually exposes more of the mandibular incisors. As a consequence, show of maxillary incisors with relaxed lips signifies youth and beauty, whereas display of mandibular incisors is a characteristic of the elderly (see Fig. 3-6). The importance of the vertical dimension in tooth display has been demonstrated in prosthetic dentistry13,14 and in orthognathic surgery involving maxillary repositioning.24,25

The guide for tooth position planning in orthodontic treatment should start with an appraisal of the position of the maxillary central incisal edge relative to the upper lip.26,27

This assessment is made with the patient's upper lip at rest, using a millimeter ruler or periodontal probe. This incisor position can be either acceptable or unacceptable, depending on the patient's age. The clinical guideline should be that the maxillary incisors should be moved in the vertical direction that improves their relationship to the resting lip position relative to the patient's age (Figs. 3-8 and 3-9; see Fig. 3-7). The relaxed lip position is the most reproducible functional position. It can and should be used as the guide,26,27 whereas forced or posed smiles may vary considerably in the same patient and cannot be considered an accurate guide for incisor positioning.27

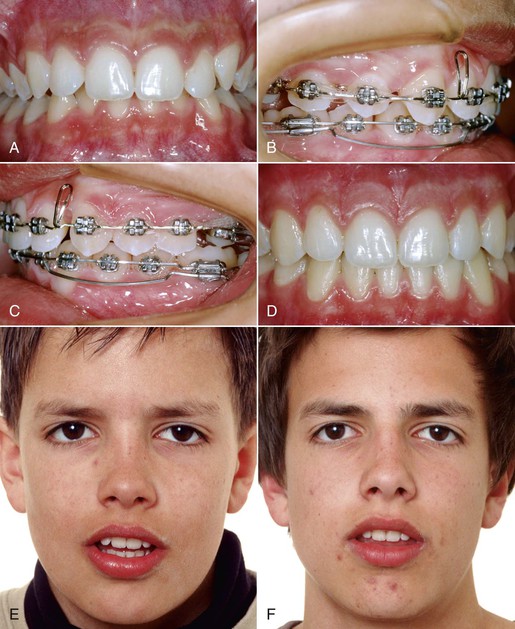

Figure 3-8 A and E, Young male patient with deep anterior overbite. E, Rest position photograph indicates that maxillary incisors should not be intruded. B and C, Mandibular incisor intrusion using 0.0175-inch × 0.025-inch CNA overlay arches from double tubes on the mandibular first molars. Final result demonstrates (D) overbite correction and (F) optimal maxillary incisor display with lips at rest.

Figure 3-9 A and E, Eighteen-year-old female with Class II, Division 2 deep overbite malocclusion. E, The anterior overbite should not be treated with maxillary incisor intrusion, since the tooth display with lips at rest is good. B-D, The maxillary incisors were merely leveled and the deep bite correction was made with intrusion of the mandibular incisors. C, Von der Heydt torquing auxiliary was used to improve the maxillary incisor inclination. F, The incisor display with relaxed lips after treatment is unchanged.

Spontaneous smiling records may also be recommended for diagnostic purposes. Because of the dynamic nature of spontaneous smiling, dynamic video recording of the spontaneous smile should be preferred.9,20,21 Lip-tooth relationships follow a consistent pattern in natural rest position and during speech and spontaneous smiling.

Sex Differences

The sexual dimorphism in anterior tooth display implies that females have significantly more maxillary and less mandibular tooth exposure than males at all ages. In a group of adults, Vig and Brundo14 found almost twice as much maxillary anterior tooth display with the lips at rest in women (3.4-mm) as in men (1.9-mm). Men displayed much more of the mandibular incisors (1.2-mm compared to 0.5-mm).

Standardized Extraoral Records

A standardized procedure for recording the incisor display in (1) rest position (Fig. 3-10; see Figs. 3-4 to 3-9) and (2) a posed smile (see Figs. 3-2 to 3-4) both before and after orthodontic treatment is recommended and will help the clinician to avoid undesirable treatment effects on the maxillary incisor reveal. Each patient should be coached and asked to achieve the same lip position at least twice in succession before a photograph is taken. In rest position (instruct the patient to say “Emma” or “Mississippi”),6,28 the teeth should be slightly apart and both the perioral soft tissue and the mandibular posture must be unstrained. In the posed smile (instruct the patient to bite together, smile, and say “Cheee …”),6 the teeth should be lightly closed. As mentioned, the analysis of incisor display during spontaneous smiling should be made with video records.

Clinical Implications for Deep Overbite Correction

Average and Low Smile Types

The correction of deep anterior overbite can be made by various combinations of incisor intrusion and molar extrusion.29,30 The treatment concepts for deep overbite cases have changed significantly during the past 10 to 15 years. This is due to the increasing attention now being paid to the esthetic importance of the vertical display of the maxillary incisors during normal speech and with relaxed lips.6,7,26 While active intrusion of maxillary incisors with intrusion arches à la Burstone, utility arches à la Ricketts, overlay base-arches, and similar approaches has previously been considered a cornerstone of deep bite correction, the risk of too much intrusion (so-called “overintrusion”) with such approaches is apparent.28,30 Overintrusion may tend to hide the maxillary incisors behind the upper lip when the patient is speaking. Lindauer et al.30 compared the outcomes from two common procedures used to reduce deep overbite: maxillary incisor intrusion using an intrusion arch and posterior eruption using an anterior biteplate. Both the intrusion arch and the biteplate procedures effectively reduced overbite significantly over a relatively short period of treatment. The intrusion arch patients displayed significant reductions in maxillary incisor display (mean change from 5.4- to 3.0-mm) accompanying documented incisor intrusion. This means that a maxillary intrusion arch will lead to a premature aged oral appearance. Such a mistake can go undetected by the orthodontist unless the upper central incisors show on speaking and smiling is recorded and analyzed properly. With increasing age of the patient and concomitant drooping of the upper lip, an unesthetic incisor display at adolescence will predictably worsen with time.9,21

In a child or adolescent patient, maxillary incisor intrusion beyond 4- to 5-mm below the upper lip at rest represents overintrusion of these teeth and unwanted aging of the patient. In a young adult between 20 and 30 years of age, there should be at least 3-mm of maxillary incisors showing. For an adult 30 to 40 years of age, approximately 1.5-mm of the maxillary incisors should show at rest position of the lips, and at age 40 to 50 years, about 1-mm should show. In patients more than 50 to 60 years of age, the maxillary incisors normally should not show at all when the lips are relaxed (see Fig. 3-6). According to Frush and Fisher,31 an optimal incisor position for adults occurs when the maxillary lateral incisors show “when the patient is speaking seriously.” The tips of the lateral incisors should show in varying degrees according to the sex and age requirements.

The tooth-to-lip position at rest should be monitored constantly throughout the orthodontic treatment. Since no orthodontist would wish to make his or her patients look older than they really are, it is important to carefully analyze each patient's tooth display on speaking before deciding whether maxillary intrusion mechanics should be used.28 In some deep overbite cases, extrusion rather than intrusion of the maxillary incisors may be indicated (see Fig. 3-7) or a combination of orthodontics and prosthetic crown lengthening with porcelain laminate veneers will be the method of choice (see Fig. 3-4).

From an esthetic point of view, the best treatment strategy in the majority of deep overbite cases is to actively intrude the mandibular rather than the maxillary incisors. This is particularly true when the curve of Spee is marked and when the six mandibular anterior teeth are above the functional occlusal plane at the start of treatment. Mandibular incisor intrusion can be achieved with segmented intrusion arches, utility arches, overlay base-arches, etc. The rate of intrusion can be controlled by recording the position of the maxillary central incisal edges relative to fixed points on the mandibular appliances. Using overlay base-arches (see Figs. 3-7 to 3-9), the mandibular incisor intrusion usually occurs at a rate of 0.5-mm per month. It should be emphasized that it is not possible to effectively intrude mandibular incisors with one continuous archwire. Compared to a conventional continuous archwire, segmented mechanics (Burstone) will produce overbite correction by (1) more incisor intrusion and (2) less molar extrusion and subsequent posterior rotation of the mandible.32,33

Another situation that calls for the use of segmented archwires happens in children with reduced anterior overbite and maxillary canines erupting in a high position.28 If a continuous leveling archwire is used, the intrusive counterforce on the incisors may overintrude them into functionally and esthetically unacceptable positions. In such instances, the first molars should be connected with a solid transpalatal bar to yield a reliable posterior anchorage unit and a cantilever wire from the extra molar tube used to bring down the canines and secure an optimal vertical incisor display after treatment.7

An alternative to incisor intrusion for deep overbite correction may be active molar extrusion. Such effects can be obtained with functional appliances, biteplates, headgears, etc.34 Molar extrusion may be of merit in a growing child with normal or low-angle face type and vertical growth pattern28 but it would be calamitous in a high-angle case and cannot be recommended in adults because of stability concerns.34

The second most common mistake in orthodontic treatment and finishing in the vertical plane is to create a straight smile line rather than an incisal smile curve.15,28,35,36 Undesirable arc flattening is probably underestimated in orthodontics. Ackerman et al.36,37 reported that as many as 32% of their patients got a flattening of the smile arc during orthodontic treatment. One reason why such changes may go unnoticed by orthodontists is that they are observed only when the patients are examined from the front.

It may seem difficult to achieve the desired parallelism between the maxillary incisors and the lower lip in smiling. In clinical practice, however, this appearance can readily be achieved if the maxillary central incisors are symmetrically positioned 0.5- to 1.5-mm longer than the lateral incisors38 (see Fig. 3-10). If the lower lip shows a marked curvature in smiling, the distoincisal edges of the maxillary central incisors can be ground slightly with a diamond instrument, as this procedure will not affect the functional occlusion.33

It is particularly undesirable to combine maxillary incisor overintrusion with a straight rather than a curved arrangement of these teeth. This display gives the impression of a typical static denture that results in the so-called “denture mouth.”28,31

High Smile Types: “Gummy” Smiles

As mentioned, a fourth category of smile line types is the “gummy” smile, defined as show of more than 4-mm of maxillary gingiva in full smiling.11 This smile type has provoked considerable interest and concern among orthodontists. Its biological mechanism appears to involve the combined effects of anterior vertical excess, an increased muscular capacity to raise the upper lip in smiling, short upper lip, and associated factors such as excessive interlabial gap at rest and excessive overjet and overbite.18,37

A different treatment strategy may be needed for patients with high lip lines than for those with average or low smile types. Treatment alternatives include various combinations of orthodontic, periodontal, and surgical therapy. The differential diagnosis should take into consideration both the amount of maxillary incisor display at rest position of the lips and the amount of gingiva shown on smiling. If the maxillary incisor show at rest is optimal, active upper incisor intrusion should not be initiated. Instead, local gingivectomies or surgical crown lengthening with removal of crestal alveolar bone39–41 should be done. Such procedures are particularly indicated in cases with altered passive eruption, excessive marginal gingivae, and short clinical crowns, since they will expose more of the anatomic crowns. When crestal alveolar bone is removed during surgical crown lengthening, the gingival margin will stabilize within 6 months at about 3-mm from the new bone level.41 Attempts to inject botulinum toxin (Botox) for neuromuscular correction of excessively gummy smiles caused by hyperfunctional upper lip elevator muscles have been reported to be effective for about 6 months but the effect is transitory.42

Treatment of the most severe gummy smiles may require maxillary superior repositioning surgery (Le Fort I osteotomy), along with reduction of the associated vertical maxillary excess.13

Midlines

Dental to Facial Midline Positions

As mentioned, it is virtually impossible to check the relationship of the upper and lower midlines to the facial midline in the normal dentist-patient positions, since these allow only a view from the side (see Fig. 3-1). However, moving the patient's head to the side of the headrest will allow direct frontal observation.6

Midline Guides

The most practical guide to locate the midline of the face is to draw an imaginary vertical line that extends through soft tissue nasion and the midpoint of the Cupid's bow in the upper lip.3,43

A line between these landmarks not only locates the position of the facial midline but also determines the direction of the midline. Whenever possible, the maxillary dental midline should be coincident with the facial midline (Figs. 3-10 to 3-13). If this is not possible, the midline between the maxillary central incisors should be strictly vertical and parallel to the facial midline.3,10,44,45

Figure 3-11 A, Adult female patient with rolled-in mandibular posterior teeth (particularly on the right side) and limited crossbite. Treatment included partial expansion in the maxillary right side. B, Uprighting of mandibular right canine, premolar, and molars was obtained by third-order bends in stainless steel archwire to provide desired lingual root torque. Note the symmetry of right and left sides after treatment.

Figure 3-12 Maxillary premolar extraction case with full and radiant smile after orthodontic treatment. Note the lingually tilted maxillary premolars (A), canted midline, and extensive buccal corridors (C) at start. Maxillary and mandibular premolars and molars were uprighted. B and D, The dental midline coincides with the facial midline.

Figure 3-13 Desirable smile esthetics in young premolar extraction patient. A and B, Occlusal views before and after treatment. D, Facial view before treatment. E, Incisor display with relaxed lips is right for her age. F, The posed smile is full and attractive due to the upright canines and premolars and the dental midline is parallel to the facial midline. C and F, The connector area between the maxillary incisors and canines correspond to the 50-40-30 rule (see text).

Esthetically Acceptable Midline Deviations

Kokich Jr. et al.10 reported an interesting interaction between maxillary central incisor midline deviation and crown angulation. As long as the dental midline was parallel to the facial midline, even a 4-mm maxillary midline deviation was not detected on photographs by dentists and laypersons. Similar findings from laypersons' perspectives were made by Springer et al.46 However, all evaluators rated a 2-mm deviation in incisor angulation (canted midline) as noticeably unattractive. A significantly slanted dental midline is displeasing and will be noticed easily. These data demonstrate that a precise dental midline is not necessary for optimal esthetics as long as the incisal crown angulation is not canted (see Figs. 3-8 to 3-13). On the other hand, if the midaxis between the right and left maxillary central incisors is markedly canted, it will look unacceptably skewed even if the incisor contact point is located in the middle of the face.

While alignment of the maxillary and mandibular dental midlines is desirable in orthodontic treatment for occlusion reasons, the mandibular midline becomes a lesser issue in esthetics. The narrowness and uniform sizes of the mandibular incisors make visualization of their midpoint more difficult.

Connector Area Versus Contact Point

Morley and Eubank3 introduced the term connector areas as a useful tool and a visual goal to optimize smile esthetics in dental patients. The connector areas are larger, broader areas than the contact points between teeth and can be defined as the zone in which two adjacent teeth appear to touch. The most esthetic relationship between the maxillary anterior teeth is referred to as the 50-40-30 rule. This rule defines the ideal connector area between the two maxillary central incisors as 50% of their clinical crown length (Fig. 3-14; see Figs. 3-2, 3-12, and 3-13). The ideal connector area between a maxillary lateral incisor and a central incisor is 40% of the central incisor's clinical crown length, and between a lateral incisor and a canine is 30% of the clinical crown length of the central incisors3 (see Fig. 3-13).

Figure 3-14 A, Nature's way of compensating for a small maxillary apical base is to tilt the maxillary posterior teeth (canines through molars) labially. This position was respected during the treatment, with outcome showing slight labial inclination of the crowns (B) to provide a full and pleasing smile (C).

The most important connector area is the one between the two maxillary central incisors. Since it should be quite long in orthodontically well-treated cases, it is clinically important to carefully check the clinical midaxis between the mesial surfaces of the central incisors before appliance removal. In cases of pre-treatment crowding it is almost always necessary to recontour these mesial surfaces by slight grinding (see Figs. 3-1, 3-3, 3-12, and 3-13). This will relocate the contact point in an apical direction to reduce or avoid interdental gingival recession47 (dark triangles between the teeth due to loss of the gingival papillae) and result in an optimally long and vertical connector area (see Figs. 3-2 and 3-12 to 3-14). If the connector area is canted undesirably, it can be improved in the finishing stages of treatment using small artistic archwire bends. A prerequisite for detecting the need for such corrections is that the patient's dentition is studied from the front.

Transverse Dimension

Most orthodontists are familiar with the fact that too little lingual root torque of the maxillary central incisors during treatment will have a negative esthetic effect in most patients. Partly due to a different reflection of the incoming light, patients with optimal incisor crown inclination are considered to look more attractive than patients who finish orthodontic treatment with large interincisal angles. The current evidence regarding the most desirable esthetic labiolingual crown inclination of the maxillary canines, premolars, and molars is limited. Thus any discussion relative to what constitutes the most esthetic positions of the upper canines and posterior teeth in different patients will be subjective.

As discussed and illustrated elsewhere,7,48,49 the fullness of the smile should be sought through adjustment of the clinical crown torque of the maxillary canines and premolars to their most esthetic appearance in different face types, rather than through nonextraction heroics or unnecessary lateral expansion and labial tipping of the maxillary dentition. Some important elements for the transverse dimension in orthodontics are:

• The labiolingual crown inclination of the terminal tooth in each quadrant that shows in smiling

• The crown inclination symmetry of contralateral teeth

• The harmony of the front-to-back tooth display curve

• The relationship between the size of the maxillary apical base and the labiolingual crown inclination of the maxillary teeth

Terminal Tooth on Smiling

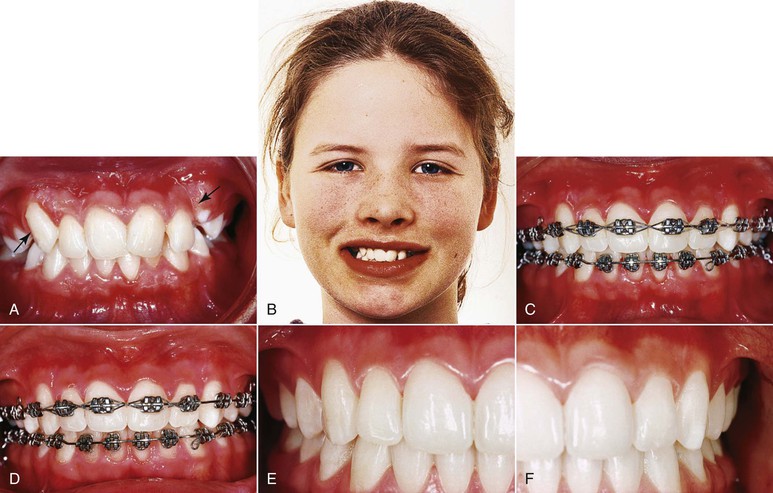

Generally speaking, about 90% of people show either the first or the second premolar as the last tooth when they are smiling.8,16 To create the illusion of smile fullness, the last premolar displayed should be positioned relatively upright42,43 (see Figs. 3-2, 3-10, and 3-11). It is particularly important to avoid a lingual inclination of the maxillary premolars in patients with a relatively small maxillary apical base (see Fig. 3-14) and in premolar extraction cases (Fig. 3-15; see Figs. 3-2, 3-12, 3-13).48,49 When there is crown inclination asymmetry between the right and left last premolar on smiling, the smile invariably appears narrower on the side where the premolar has more tilt.47

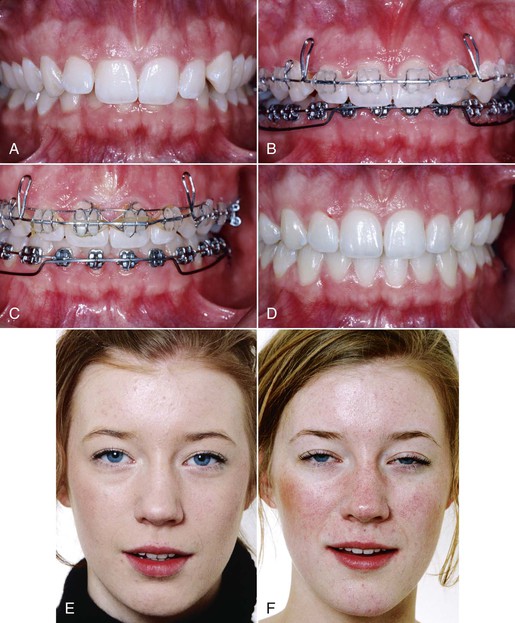

Figure 3-15 A and B, A markedly different clinical crown inclination between maxillary right and left canine (arrows) at start in young female patient. Due to the individualized torque with intentional lingual root torque bends in archwire, the right canine improved its inclination at 9 months (C) and 12 months (E) until it was upright and symmetrical with the left canine at the end of treatment (D and F). Also note the uprighted positions of maxillary and mandibular posterior teeth (A, D, and F).

The torque prescriptions for most preadjusted appliance systems tend to create too much lingual crown inclination of maxillary and mandibular canines and posterior teeth.50 The view that the canines and premolars should have considerable lingual crown inclination (Fig. 3-16) in an optimally treated orthodontic case51 irrespective of tooth size, jaw size, face type, and facial expressivity is disputed from an esthetic perspective.

Figure 3-16 The optimal lingual crown inclination in normally occluded (A) upper and (B) lower posterior crowns according to Andrews.51 C, Progressive medial tipping of the axial inclinations of the teeth according to Morley and Eubank.3

The normative crown inclination values proposed by Andrews51 (see Fig. 3-16) that have influenced available preadjusted appliance systems were based on careful study of 120 nonorthodontic patients with normal occlusion and teeth that were “straight and pleasing in appearance” and 1150 successfully treated orthodontic cases. Although this information has been of great value to our profession, study of already treated orthodontic cases may not be the optimal basis for optimal crown torque estimations from an esthetic perspective. Indeed, laypersons prefer straight upper canines and premolars according to an extensive computer-based survey based on slider technology on a large number of U.S. patients (n = 243).52

Crown Inclination Symmetry on Contralateral Teeth

Crown inclination symmetry of the contralateral teeth on the right and left sides of the maxilla and mandible will contribute to an optimally esthetic appearance (see Figs. 3-11 to 3-15). It is generally easier said than done to obtain bilateral crown inclination symmetry on canines and premolars (see Fig. 3-15). A prerequisite to detect asymmetries is to view the patient directly from the front at the start of orthodontic therapy so that the necessary correction bends can be made in the archwires.

Front-to-Back Progression

The front-to-back progression of the maxillary canine, premolars, and molars is a critical factor for the display of the dentition when the patient is speaking and smiling. The principles of gradation and smoothness must be observed, so the decrease in size and detail occurs gradually.5 Lombardi5 noted that the teeth should have a harmonious perspective from the dominant central incisors transitioning posteriorly, with each tooth in harmonious proportion to those adjacent. The apparent widths may or may not be in “golden proportion”53,54 to one another. Analyzing students in California, Preston54 found the golden proportion between the perceived width of the maxillary central and lateral incisors in only 17% of the cases and between any perceived lateral incisor and canine widths in none of the cases. He claimed that there is nothing mystical or exclusively correct about the use of the golden proportion. Such use may well provide a pleasing outcome, as might many other approaches (see Figs. 3-10 to 3-15 and 3-18). From a clinical point of view, it may be more important to avoid any interruption of the harmony and gradual smoothness. This implies that canines and premolars with excessive lingual tipping (Figs. 3-17 and 3-18) or a premolar placed too far buccally5 will lessen the harmony of the tooth display curve laterally and reduce the esthetic impression.

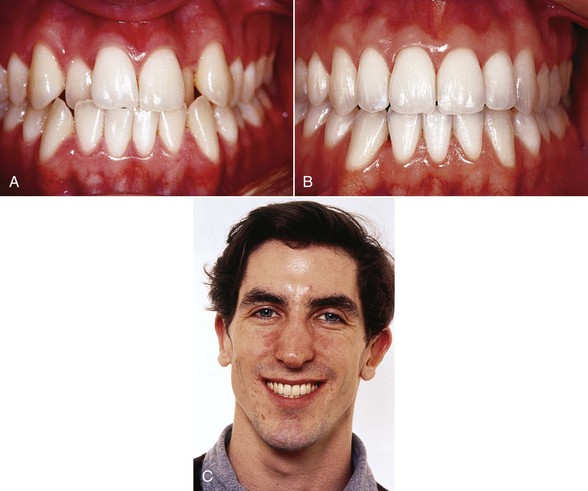

Figure 3-17 Undesirable smile esthetics in nonextraction Class II, Division 1 female patient. Marked lingual inclination of maxillary canines and premolars (A) remained undetected at the end of treatment (B) and 17 years later (C), providing a narrow smile with extensive buccal corridors throughout therapy and follow-up (D and E). Preadjusted appliance was used with negative torque values for canine and premolar brackets and no intentional third-order torquing bends.

Figure 3-18 Adolescent female patient with mild bimaxillary crowding (A) treated without extraction and without lateral expansion and/or incisor proclination (B). Space along the dental arches was provided by stripping oval premolars and triangular incisors toward their ideal shapes. The improved fullness of the smile (compare C and D) is primarily due to intentional uprighting (lingual root torque placed in the archwires) of canines and posterior teeth.

Apical Base Size and Crown Inclination Variations

Regarding jaw size, it appears to be a general rule for obtaining optimal esthetics that the smaller the maxillary apical base, the more labial tilt may be given to the canines and premolars to allow a broader smile (see Fig. 3-14). This will copy nature's way of compensating for different sizes of maxillae. For most patients, optimal esthetics will be achieved with upright canines or a very mild lingual crown inclination (see Figs. 3-2, 3-3, 3-9, 3-11 to 3-15, and 3-18). Too much lingual crown inclination of the canines generally will disrupt the harmony of the front-to-back tooth display curve (see Fig. 3-17).

Buccal Corridors

Several studies have reported laypersons' perceptions of and reactions to the buccal corridors.31,35,46,52,55 None found a specific relationship between this trait and smile esthetics. However, excessive buccal corridors are unesthetic to both orthodontists and laypersons.46,55,56 Frush and Fischer31 considered the buccal corridor to be a normal feature of a dentition that prevents the “sixty tooth smile” that is often characteristic of a denture. Apparently, the labiolingual inclination of the maxillary canine and premolars is as important as or more important than the presence or absence of dark buccal corridors for reflection of dental arch fullness (Figs. 3-19 and 3-20; see Fig. 3-18). It should be emphasized that dark shadows between the buccal surfaces of the dentition and the corners of the mouth are more apparent on frontal photographs than in real life, as they are generally due to inadequate flash lighting of the posterior areas of the mouth in routine photography.36,37 If the pre-treatment maxillary dental arch is acceptable with regard to shape and width, it may seem preferable in terms of long-term stability to obtain smile fullness by intentionally adding buccal crown torque to lingually inclined canines and premolars during treatment (see Figs. 3-10 to 3-13 and 3-18). Maxillary lateral expansion is indicated whenever the maxillary and mandibular dental arches are notably constricted in the beginning, whether or not posterior crossbite is present. Excessive intentional lateral expansion of the dental arches is likely to introduce a disequilibrium and long-term relapse.48,49

Figure 3-19 Two male patients demonstrate the wide range of individual variation in crown inclination of posterior teeth (canines through molars). A and C, The young boy has a large maxillary apical base with marked lingual tilt of the teeth. B and D, The older patient has a small maxilla, a large mandible, and labial tilt of the teeth.

Figure 3-20 Importance of the premolar crown for fullness of the smile. A young female patient at the end of orthodontic treatment (A and C) and 5 years later (B and D). The post-treatment intraoral result may appear optimal according to the prevailing concepts (compare with Fig. 3-16, A and C). However, both smile photographs show that the lingually tilted premolars are almost hidden behind the upright canines. The smile is much narrower than for the patient with upright premolars in Figure 3-18, D.

The principles and considerations discussed above may be supplemented by a discussion of the optimal crown torque from an esthetic perspective for individual teeth, as follows.

Maxillary Canine

There is a very large individual variation in labiolingual inclination of the maxillary canines and premolars between patients. The patient in Figure 3-19, A and C, has a broad maxilla and marked lingual tipping of all teeth. In marked contrast, the patient in Figure 3-19, B and D, has a narrow maxillary apical base and a pronounced labial tilt of all clinical crowns. The crown torque discrepancies between these two patients demonstrate why it is unrealistic to try to produce the same orthodontic treatment result for both of them; it is also obvious that they cannot be treated to optimum esthetics using the same preadjusted bracket prescription system without marked third-order archwire bends. An individualized esthetic goal should be set for each patient before the orthodontic treatment is started. Excessive lingual tipping of the maxillary canine is undesirable for esthetic reasons, whether it occurs unilaterally or bilaterally (see Figs. 3-17 and 3-18).52

It is surprisingly common that at the end of fixed appliance treatment, maxillary canine and premolar crowns are tipped lingually because the prescription in many modern brackets provides negative torque (lingual crown torque) for these teeth.57,58 This affects smile esthetics negatively, especially in patients with narrow and tapered arch forms, by making the canines less prominent (see Fig. 3-17) and causing the first premolars to almost disappear on smile (see Fig. 3-20). To obtain a broader arch and more pleasing smile, the solution is not further lateral expansion across the premolars, but to use lingual root torque so that the crowns are uprighted. This gives the appearance of a broader smile without the risk of relapse that accompanies such expansion. Existing data confirm that the inclinations of these teeth remain as they were at the end of treatment.58,59

Uprighting the canines and premolars in this way does elongate their lingual cusps and potentially could lead to occlusal interferences that would be difficult for patients to tolerate. If this occurs (which is unlikely), reduction of the height of the lingual cusps is indicated.

To achieve symmetry of labiolingual crown inclination between the teeth on the right and left sides of the mouth, intentional individualization is needed (see Fig. 3-15). The easiest and most practical way to achieve symmetry is to carefully study each case from the front and make the necessary archwire bends early in treatment (see Fig. 3-15).

It is apparent from these and other cases that (1) the preferred labiolingual crown inclination of the maxillary canine from an esthetic viewpoint in a majority of cases is relatively upright7,52 and (2) that pre-treatment asymmetries in crown inclination between right and left canines will remain after orthodontic therapy if no intentional measures are taken to correct them. Such adjustments may involve the use of individual archwire bends at different periods during treatment or possibly the use of custom brackets specifically engineered for the individual needs of each patient.

Maxillary First and Second Premolars

Premolars with an upright position will produce a broader smile than premolars that are tipped lingually. Particularly when orthodontic treatment has resulted in lingual tipping of the maxillary premolars behind upright canines, the smile becomes undesirably narrow in the posterior segments and does not reach an optimal fullness (see Fig. 3-20).

For this reason, the esthetically preferable first and second premolar crown torque for most patients is around 0 degrees.7,52 For patients with a wide maxillary apical base, a few degrees of lingual crown torque may be desirable. For patients with a small maxillary apical base, upright premolar crowns or even some labial crown inclination may produce a nice display of their dentitions (see Fig. 3-14).

Maxillary First Molar

Only a small percentage of a population show the maxillary first molars when smiling.8 For these patients, the molars should be relatively straight to contribute to a full smile (Fig. 3-21).

Figure 3-21 When the terminal teeth displayed in the smile are the maxillary first molars (A), their position should be upright to produce fullness of smile (B and C) (same patient as in Fig. 3-3).

Mandibular Canine

The optimal outcome of orthodontic treatment regarding the mandibular canines is to achieve (1) relatively upright positions when viewed from the front (see Figs. 3-11 and 3-21) and (2) bilateral crown inclination symmetry (see Figs. 3-9, 3-11, and 3-13). Upright rather than lingually tipped mandibular canines allow more labial crown torque of the maxillary canines, producing a broader smile. Many preadjusted prescription appliances place lingual crown torque in the mandibular canines, which appears undesirable both esthetically and functionally. Particularly when the mandibular canines are tipped lingually before orthodontic treatment is started, appliances with built-in lingual crown torque tend to produce an excessive lingual tipping of the canines (Fig. 3-22). The correction of such tipping toward the lingual is time-consuming and difficult and may remain unnoticed at the end of treatment (see Figs. 3-14 and 3-22). A mandibular canine torque prescription that induces some labial crown torque (lingual root torque) will counteract such side effects.

Figure 3-22 Unintentional excessive lingual tipping of mandibular canines (and premolars) during orthodontic treatment (A and B) is difficult and time consuming to correct and may remain undercorrected at the end of treatment (C). Note the right-left asymmetry of canine crown inclination throughout treatment.

Mandibular Premolars and Molars

A common side effect of routine orthodontic treatment with both preadjusted and standard edgewise appliances is that the crowns of the mandibular posterior teeth tend to tip lingually.50 This is undesirable not only from an esthetic point of view, but also for functional reasons. If the mandibular premolars and molars receive marked lingual crown torque, the lingual cusps of the maxillary posterior teeth may erupt into occlusion with their lingual cusps hanging down. This arrangement may cause balancing side interferences in side movements of the mandible. This side effect can be avoided by careful clinical observation and archwire bending and/or by using nontorqued attachments for the mandibular posterior teeth, including the second molars.

How to Achieve Both an Optimal Smile and Dental Stability

The available research evidence regarding long-term stability of orthodontic treatment results implies that the patient's pre-treatment mandibular intercanine width and mandibular arch form may be the optimal guide to future dental and arch form stability.60–63

If these measures are within a normal range, which implies that the intercanine width is around 25- to 26-mm, the mandibular incisors are in front of the A-pogonion line, and the arch form is symmetrical, with no need for transverse uprighting (buccal crown torque) of premolars and molars, then the mandible should be treated orthodontically without incisor proclination and lateral expansion (see Figs. 3-9, 3-12, 3-13, and 3-18). Mild to moderate dental crowding is managed by mesiodistal enamel reduction (stripping).

The maxillary dental arch is placed on top of and coordinated with the mandible. The original maxillary arch form is respected but frequently has to be rounded and slightly expanded posteriorly (see Fig. 3-13) to occlude properly with the mandibular teeth.48,49 With this approach, smile fullness is sought not through lateral expansion or tipping of the maxillary dentition but rather through intentional adjustment of the labiolingual crown inclination of the maxillary canines and premolars to their most esthetic appearance (see Figs. 3-11 to 3-13).48 Maxillary lateral expansion is indicated, however, whenever the maxillary and mandibular arches are notably constricted in the beginning, whether or not a posterior crossbite is present.

Clinical Guidelines

Vertical Dimension

The following guidelines are recommended to obtain an optimally esthetic tooth display in normal conversation and on smiling:

• Study the patient's dentition directly from the front to make a reliable esthetic evaluation. With the patient in the dental chair, move the patient's head to the side of the headrest, which allows an “eye-to-eye” perspective.

• Routinely take extraoral photographs with the lips at rest before and after treatment to record the maxillary incisor display. A short video that shows the patient speaking and smiling joyfully is helpful to record the spontaneous gingival display.

• Provide a curve of the maxillary incisors that is parallel to the inner contour of the lower lip on smiling. This is generally achieved by making the maxillary central incisors 0.5- to 1.5-mm longer than the lateral incisors.

• Avoid actively intruding the maxillary incisors when the pre-treatment vertical position is normal for the patient's age. Do not overintrude and hide the maxillary incisors behind the upper lip.

• Establish an age-appropriate vertical incisor display in rest position and normal conversation for each orthodontic patient.

Midlines

The following guidelines may be clinically useful for optimal smile design in orthodontic patients:

• A vertical line from nasion to the base of the philtrum may be the most practical guide to locate the facial midline.

• A precise dental midline coincident with the facial midline is not necessary for optimal esthetics.

• Moderate maxillary midline deviation is acceptable to most persons as long as the central incisor crown angulation is not significantly canted.

• Securing optimal connector areas between the maxillary anterior teeth according to the 50-40-30 rule is useful for esthetic smile design.

• The connector area between the two maxillary central incisors should be long (approximately half of their clinical crown lengths), vertical, and parallel to the facial midline.

Transverse Dimension

The most desirable and esthetic crown inclinations are not evidence-based but the following clinical recommendations are useful:

• Provide an individualized, esthetic, symmetrical labiolingual crown inclination of canines and premolars for each patient.

• Crown inclination asymmetries between contralateral canines and premolars in the right and left side of the mouth in the same patient are common. They must be (1) recognized early in treatment by studying the dentition from the front and (2) intentionally corrected by archwire torquing (or possibly by custom-made bracket torque prescriptions). Otherwise, the finished result will be asymmetrical with regard to clinical crown inclination.

• The terminal teeth shown on smiling should be straight to provide smile fullness. In about 90% of cases, the terminal teeth will be the maxillary first or second premolars.

• A smooth, gradual front-to-back tooth display curve laterally provides harmony and beauty to the treatment result. Any disruption will reduce the esthetic outcome.

• Avoid tipping the mandibular canines, premolars, and molars lingually during the orthodontic treatment.

• The secret to excellence in orthodontics is to learn to see important details in the dentition as they occur before, during, and after treatment.

Summary

This chapter discussed some esthetic elements of tooth display and smile design associated with orthodontic treatment. Normative standards of the lip-incisor relationships were provided. The importance of an individual patient's display of the dentition during speech and on smiling was evaluated (1) in the vertical dimension, (2) with regard to midlines, and (3) in the transverse dimension. Multiple clinical guidelines were provided. Together, these clinical recommendations should be of value to improve the esthetic outcome of contemporary orthodontic treatment results.

References

1. Ackerman JL, Proffit WR, Sarver DM. The emerging soft tissue paradigm in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning. Clin Orth Res. 1999;2:49–52.

2. Proffit WR. The soft tissue paradigm in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning: a new view for a new century. J Esthet Dent. 2000;12:46–49.

3. Morley J, Eubank J. Macroesthetic elements of smile design. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:39–45.

4. Nash DA. Professional ethics and esthetic dentistry. J Am Dent Assoc. 1988;115:7E–9E.

5. Lombardi RE. The principles of visual perception and their clinical application to denture esthetics. J Prosthet Dent. 1973;29:358–382.

6. Zachrisson BU. Esthetic factors involved in anterior tooth display and the smile: vertical dimension. J Clin Orthod. 1998;32:432–445.

7. Zachrisson BU, Sinclair P. Master Clinician. Bjorn U. Zachrisson DDS, MSD, PHD. J Clin Orthod. 2012;41:531–557.

8. Tjan AHL, Miller GD, The JG. Some esthetic factors in a smile. J Prosthet Dent. 1984;51:24–28.

9. Desai S, Upadhyay M, Nanda R. Dynamic smile analysis: change with age. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;136:310.e1–310.e10.

10. Kokich VO Jr, Kiyak HA, Shapiro PA. Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics. J Esthet Dent. 1999;11:311–324.

11. Van der Geld P, Oosterveld P, Schools J, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. Smile line assessment comparing quantitative measurement and visual estimation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:174–180.

12. Peck S, Peck L, Kataja M. Some vertical lineaments of lip position. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1992;101:519–524.

13. Peck S, Peck L, Kataja M. The gingival smile line. Angle Orthod. 1992;62:91–100.

14. Vig RG, Brundo GC. The kinetics of anterior tooth display. J Prosthet Dent. 1978;39:502–504.

15. Sarver DM. The importance of incisor positioning in the esthetic smile: the smile arc. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;120:98–111.

16. Sarver DM, Ackerman MB. Dynamic smile visualization and quantification: part 1. Evolution of the concept and dynamic records for smile capture. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;124:4–12.

17. Mack MR. Vertical dimension: a dynamic concept based on facial form and oropharyngeal function. J Prosth Dent. 1991;66:478–485.

18. Mack MR. Perspective of facial esthetics in dental treatment planning. J Prosth Dent. 1996;75:169–176.

19. Dong JK, Jin TH, Cho HW, Oh SC. The esthetics of the smile: a review of some recent studies. Int J Prosthodont. 1999;12:9–19.

20. Van der Geld P, Oosterveld P, Berge SJ, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. Tooth display and lip position during spontaneous and posed smiling in adults. Acta Odont Scand. 2008;66:207–213.

21. Van der Geld P, Oosterveld P, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. Age-related changes of the dental aesthetic zone at rest and during spontaneous smiling and speech. Europ J Orthod. 2008;30:366–373.

22. Rubin LR. The anatomy of a smile: its importance in the treatment of facial paralysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974;53:384–387.

23. Peck S, Peck H. The aesthetically pleasing face: an orthodontic myth. Trans Eur Orthod Soc. 1971;47:175–185.

24. Rosen HM, Ackerman JL. Porous block hydroxyapatite in orthognathic surgery. Angle Orthod. 1991;61:185–191.

25. Turley PK. Orthodontic management of the short face patient. Semin Orthod. 1996;2:138–152.

26. Spear FM, Kokich VG, Mathews DP. Interdisciplinary management of anterior dental esthetics. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:160–169.

27. Burstone CJ, Nanda R. JCO interviews Charles J. Burstone DDS, MS. part 1 facial esthetics. J Clin Orthod. 2007;41:79–87.

28. Zachrisson BU. Mechanical intrusion of maxillary incisors: a treatment strategy to be abandoned? World J Orthod. 2002;3:358–364.

29. Shroff B, Yoon WM, Lindauer SJ, Burstone CJ. Simultaneous intrusion and retraction using a three-piece base arch. Angle Orthod. 1997;67:455–462.

30. Lindauer SJ, Lewis SM, Shroff B. Overbite correction and smile aesthetics. Semin Orthod. 2005;11:62–66.

31. Frush JP, Fisher RD. The dynesthetic interpretation of the dentogenic concept. J Prosthet Dent. 1958;8:558–581.

32. Weiland FJ, Bantleon HP, Droschl H. Evaluation of continuous arch and segmented arch leveling techniques in adult patients: a clinical study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1996;110:647–652.

33. AlQabandi A, Sadowsky C, Sellke T. A comparison of continuous archwire and utility archwires for leveling the curve of Spee. World J Orthod. 2002;3:159–165.

34. Simons ME, Joondeph DR. Change in overbite: a ten-year postretention study. Am J Orthod. 1973;64:349–367.

35. Hulsey CM. An esthetic evaluation of lip-teeth relationships present in the smile. Am J Orthod. 1970;57:132–144.

36. Ackerman JL, Ackerman MB, Brensinger CM, Landis JR. A morphometric analysis of the posed smile. Clin Orth Res. 1998;1:2–11.

37. Ackerman MB, Ackerman JL. Smile analysis and design in the digital era. J Clin Orthod. 2002;36:221–236.

38. Brisman AS. Esthetics: a comparison of dentists’ and patient's concepts. J Am Dent Assoc. 1991;100:345–352.

39. Kokich VG. Esthetics: the orthodontic-periodontic-restorative connection. Semin Orthod. 1996;2:21–30.

40. Garber DA, Salama MA. The aesthetic smile: diagnosis and treatment. Periodontol 2000. 1996;11:18–28.

41. Brägger U, Lauchenauer D, Lang NP. Surgical lengthening of the clinical crown. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:58–63.

42. Polo M. Botulum toxin type A (Botox) for the neuromuscular correction of excessive gingival display on smiling (gummy smile). Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2008;133:1955–2003.

43. Zachrisson BU. Dental to facial midline positions. World J Orthod. 2001;2:266–269.

44. Beyer JW, Lindauer SJ. Evaluation of dental midline position. Semin Orthod. 1998;4:146–152.

45. Johnston CD, Burden DJ, Stevenson MR. The influence of dental to facial midline discrepancies on dental attractiveness ratings. Eur J Orthod. 1999;21:517–522.

46. Springer NC, Chang C, Fields HW, et al. Smile esthetics from the layperson's perspective. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:e91–e101.

47. Tarnow DP, Magner AW, Fletcher P. The effect of the distance from the contact point to the crest of bone on the presence or absence of the interproximal dental papilla. J Periodontol. 1992;63:995–996.

48. Zachrisson BU. Making the premolar extraction smile full and radiant. World J Orthod. 2002;3:260–265.

49. Zachrisson BU. Maxillary expansion: long-term stability and smile esthetics. World J Orthod. 2001;2:266–272.

50. Ugur T, Yukay F. Normal faciolingual inclinations of tooth crowns compared with treatment groups of standard and pretorqued brackets. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1997;112:50–57.

51. Andrews LF. The six keys to normal occlusion. Am J Orthod. 1972;62:296–309.

52. Ker AJ, Chan R, Fields HW, Beck M, Rosenstiel S. Esthetics and smile characteristics from the layperson's perspective: a computer-based survey study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:1318–1327.

53. Ricketts RE. The biologic significance of the divine proportion. Am J Orthod. 1982;81:351–370.

54. Preston JD. The golden proportion revisited. J Esthet Dent. 1993;5:247–251.

55. Martin AJ, Buschang PH, Boley JC, Taylor RW, McKinney TW. The impact of buccal corridors on smile attractiveness. Europ J Orthod. 2007;29:530–537.

56. Ioi H, Kang S, Shimomura T, et al. Effects of buccal corridors on smile esthetics in Japanese and Korean orthodontists and orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;142:459–465.

57. Zachrisson BU. Facial esthetics: guide to tooth positioning and maxillary incisor display. World J Orthod. 2007;8:190–196.

58. Zachrisson BU. Proper quality orthodontics vs the new mechanical “systems.”. World J Orthod. 2007;8:412–419.

59. Zachrisson BU. Buccal uprighting of canines and premolars for improved smile esthetics and stability. World J Orthod. 2006;7:406–412.

60. Little RM, Wallen TR, Riedel RA. Stability and relapse of mandibular anterior alignment: first premolar extraction cases treated by traditional edgewise orthodontics. Am J Orthod. 1981;80:349–365.

61. Little RM, Riedel RA, Årtun J. An evaluation of changes in mandibular anterior alignment from 10 to 20 years postretention. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1988;93:423–428.

62. Felton JM, Sinclair PM, Jones DL, Alexander RG. A computerized analysis of the shape and stability of mandibular arch form. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1987;92:478–483.

63. Dyer KC, Vaden JL, Harris EF. Relapse revisited—again. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;142:221–227.