Care of the Patient With a Gallbladder, Liver, Biliary Tract, or Exocrine Pancreatic Disorder

Objectives

1. Discuss nursing interventions for the diagnostic examinations of patients with disorders of the gallbladder, liver, biliary tract, and exocrine pancreas.

2. Explain the etiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, assessment, diagnostic tests, medical management, and nursing interventions for the patient with cirrhosis of the liver, carcinoma of the liver, hepatitis, liver abscesses, cholecystitis, cholelithiasis, pancreatitis, and cancer of the pancreas.

3. Discuss specific complications and teaching content for the patient with cirrhosis of the liver.

4. Define jaundice and describe signs and symptoms that may occur with jaundice.

5. State the six types of viral hepatitis, including their modes of transmission.

6. List the subjective and objective data for the patient with viral hepatitis.

7. Discuss the indicators for liver transplantation and the immunosuppressant drugs to reduce rejection.

8. Discuss the two methods of surgical treatment for cholecystitis and cholelithiasis.

Key Terms

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Cooper/foundationsadult/

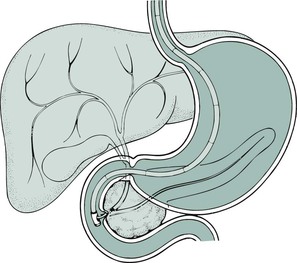

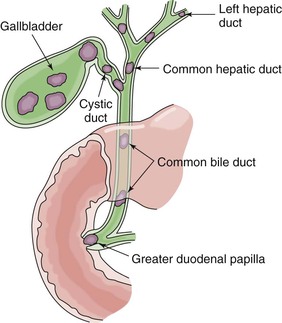

Chapter 44 discussed the anatomy and function of the organs of the gastrointestinal system, as well as care of the patient with disorders involving the gastrointestinal system. This chapter discusses the care of the patient with disorders involving the accessory organs of the digestive system; specifically, the liver, ![]() the gallbladder, and the exocrine pancreas. These organs assist in digestion in various ways.

the gallbladder, and the exocrine pancreas. These organs assist in digestion in various ways.

Laboratory and Diagnostic Examinations in the Assessment of the Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Systems

Serum Bilirubin Test

Bilirubin is the pigment that gives bile its yellow-orange color. It is formed when old or damaged red blood cells disintegrate and release their hemoglobin, which is broken down into its component parts, including heme. The heme in turn is converted into bilirubin. Unconjugated (water-insoluble; also called indirect) bilirubin passes through the bloodstream to the liver, where it is converted into conjugated (water-soluble; also called direct) bilirubin. From here the bilirubin is expelled into the bile. Normal values are as follows:

Rationale

Total serum bilirubin determination measures both direct and indirect bilirubin. The total serum bilirubin level is the sum of the direct and indirect bilirubin levels. Testing for bilirubin in the blood provides valuable information for the diagnosis and evaluation of liver disease, biliary obstruction, and hemolytic anemia. Jaundice, the discoloration of body tissues caused by abnormally high blood levels of bilirubin, is visible when the total serum bilirubin exceeds 2.5 mg/dL.

Nursing Interventions

Keep the patient on NPO (nothing by mouth) status until after the blood specimen is drawn. Inform the patient regarding blood draws and what test is being performed. Monitor the venipuncture site for bleeding.

Liver Enzyme Tests

The normal values for liver enzyme test results are as follows:

• AST (aspartate aminotransferase; formerly serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase [SGOT]): Adult: 0 to 35 units/L. The AST level is elevated in myocardial infarction, hepatitis, cirrhosis, hepatic necrosis, hepatic tumor, acute pancreatitis, and acute hemolytic anemia.

• ALT (alanine aminotransferase; formerly serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase [SGPT]): Adult or child: 4 to 36 units/L. The ALT level is elevated in hepatitis, cirrhosis, hepatic necrosis, and hepatic tumors and by hepatotoxic drugs.

• LDH (lactic acid dehydrogenase): Adult: 100 to 190 units/L. Values are increased in myocardial infarction, pulmonary infarction, hepatic disease (e.g., hepatitis, active cirrhosis, neoplasm), pancreatitis, and skeletal muscle disease.

• Alkaline phosphatase: Adult: 30 to 120 units/L. The alkaline phosphatase level is elevated in obstructive disorders of the biliary tract, hepatic tumors, cirrhosis, hepatitis, primary and metastatic tumors, hyperparathyroidism, metastatic tumor in bones, and healing fractures.

• GGT (gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase): Males and females older than age 45 years: 8 to 38 units/L; females younger than age 45 years: 5 to 27 units/L. Levels are elevated in liver cell dysfunction such as hepatitis and cirrhosis; in hepatic tumors; with the use of hepatotoxic drugs; in jaundice; and in myocardial infarction (4 to 10 days after), heart failure, alcohol ingestion, pancreatitis, and cancer of the pancreas.

Rationale

The liver is a storehouse of many enzymes. Injury or diseases affecting the liver cause release of these intracellular enzymes into the bloodstream, and their levels become elevated. Some of these enzymes are also produced in other organs, and injury or disease affecting these organs will raise the serum level. Therefore, although elevation of these serum enzymes is found in pathologic liver conditions, the test is not specific for liver diseases alone.

Nursing Interventions

Provide information to the patient regarding blood draws and what test is being performed. Monitor the venipuncture site for bleeding.

Serum Protein Test

The normal values for serum protein test results are as follows.

Rationale

One way to assess the liver's functional status is to measure the products it synthesizes. One of these products is protein, especially albumin. When a disorder or disease affects liver cells (i.e., hepatocytes), they lose their ability to synthesize albumin and the serum albumin level falls markedly. A low serum albumin level may also result from excessive loss of albumin into urine (as in nephrotic syndrome) or into third-space volumes (as in ascites), as well as in liver disease, increased capillary permeability, or protein-calorie malnutrition.

Nursing Interventions

Provide information to the patient regarding blood draws and what tests are being performed. Monitor the venipuncture site for bleeding.

Oral Cholecystography

Rationale

The oral cholecystogram (OCG) provides roentgenographic visualization of the gallbladder after the oral ingestion of a radiopaque, iodinated dye. Adequate visualization requires concentration of the dye within the gallbladder. An OCG (also called a gallbladder [or GB] series) is less accurate than gallbladder ultrasound imaging and is less commonly used to visualize the biliary tree. An OCG will not be able to visualize the biliary tree in the patient with jaundice. Adequate dye concentration in the gallbladder depends on the following factors:

• The patient's ingestion of the correct number of dye tablets the evening before the examination

• Adequate absorption of the dye from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract; vomiting or diarrhea does not allow sufficient absorption of the dye

• Abstinence from food (especially a fatty meal) after midnight the night before and the morning of the test

• Uptake from the portal system and excretion of the dye by the liver

Nursing Interventions

To prevent an allergic reaction, the nurse determines whether the patient is allergic to iodine because the dye typically used for this test is iodine-based. If the patient is not allergic to iodine, administer six tablets orally (e.g., iopanoic acid [Telepaque], iodalphionic acid [Priodax], or ipodate [Oragrafin]), one every 5 minutes, beginning after the evening meal. The patient is put on NPO status from midnight. The patient may be given a high-fat meal or beverage to stimulate emptying of the gallbladder after the test has begun. No other food or fluids are allowed until after the examination.

Intravenous Cholangiography

Rationale

In intravenous cholangiography, intravenously administered radiographic dye is concentrated by the liver and secreted into the bile duct. The intravenous cholangiogram (IVC) allows visualization of the hepatic and common bile ducts and also the gallbladder if the cystic duct is patent. An IVC is used to demonstrate stones, strictures, or tumors of the hepatic duct, common bile duct, and gallbladder. Intravenous cholangiography is a less commonly used method of visualizing the biliary tree. It should not be used in the jaundiced patient unless it is determined that there are no blocked ducts.

Operative Cholangiography

In operative cholangiography the common bile duct is directly injected with radiopaque dye. Stones appear as radiolucent shadows, and the presence of tumors will cause partial or total obstruction of the flow of dye into the duodenum. Visualization of the biliary duct structures provides the surgeon with a “road map” of a difficult anatomical area. This reduces the possibility of inadvertently injuring the common duct.

If common duct stones are suspected, a cholecystectomy as well as a common duct exploration (CDE) must be performed. When intraoperative cholangiography is used routinely, CDE is performed only on those with positive cholangiograms.

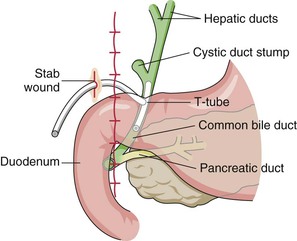

T-Tube Cholangiography

Rationale

T-tube cholangiography (postoperative cholangiography) is performed to diagnose retained ductal stones postoperatively in the patient who has undergone a cholecystectomy and a common bile duct (CBD) exploration to demonstrate good flow of contrast into the duodenum. The test is performed through a T-shaped rubber tube that the surgeon places in the bile duct during the operation. The end of the T-tube exits through the abdominal wall, where dye is injected and radiographic films are taken.

Nursing Interventions

During the preoperative phase ensure that the patient is not allergic to iodine. Preparation of the patient also includes maintaining NPO status after midnight and until the examination is completed. Administer a cleansing enema on the morning of the examination, if ordered.

Postoperatively, the patient is protected from sepsis by connecting the T-tube (if left in place) to a sterile closed-drainage system. If the T-tube is removed, cover the T-tube tract site with a sterile dressing to prevent bacteria from entering the ductal system.

Ultrasonography of the Liver, the Gallbladder, and theBiliary System

Rationale

Ultrasonography (ultrasound, echogram) is an imaging technique that visualizes deep structures of the body by recording the reflections (echoes) of ultrasonic waves directed into the tissues. This diagnostic test is not effective in examining all tissue because ultrasound waves do not pass through structures that contain air, such as the lungs, the colon, or the stomach. Although fasting is preferred, it is not necessary for ultrasonography. Because ultrasound requires no contrast material and has no associated radiation, it is especially useful for patients who are allergic to contrast media or are pregnant. Ultrasound is used with increasing frequency to corroborate data already obtained by “questionable positive” cholangiograms, liver scans, and OCGs. Gallstones are easily detected with ultrasound.

Nursing Interventions

The patient is on NPO status from midnight prior to the test. If the patient has had recent barium contrast studies, request an order for laxatives because ultrasound cannot penetrate barium, and the study will not be adequate.

Gallbladder Scanning

Rationale

The biliary tract can be evaluated safely, accurately, and noninvasively by intravenous (IV) injection of technetium (99Tc; technetium-99m), and positioning the patient under a camera to record distribution of the tracer in the liver, biliary tree, gallbladder, and proximal small bowel. The primary use of this study is in the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis. This procedure is superior to oral cholecystography, ultrasonography, and computed tomography (CT) scanning of the abdomen for the detection of acute cholecystitis. Hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scanning is also useful for identifying diffuse hepatic disease (such as cirrhosis or neoplasm) and a nonfunctioning gallbladder.

Nursing Interventions

Reassure the patient that exposure to radioactivity is minimal, because only a trace dose of the radioisotope is used. The patient is on NPO status from midnight until the examination is complete.

Needle Liver Biopsy

Rationale

Needle liver biopsy is a safe, simple, and valuable method of diagnosing pathologic liver conditions. A specially designed needle is inserted through the skin (making it a percutaneous procedure), between the sixth and seventh or eighth and ninth intercostal space, and into the liver. The patient lies supine with the right arm over the head. The patient is instructed to exhale fully and not breathe while the needle is inserted. This procedure is often done using ultrasound or CT guidance. A piece of hepatic tissue is removed for microscopic examination. The tissue sample is placed into a labeled specimen bottle containing formalin and sent to the pathology department. Percutaneous liver biopsy is used in the diagnosis of various liver disorders, such as cirrhosis, hepatitis, drug-related reactions, granuloma, and tumor.

Nursing Interventions

After the health care provider has explained the procedure to the patient the nurse verifies that the patient has signed the consent form. Ensure that measurements of platelets, clotting or bleeding time, prothrombin time, and International Normalized Ratio (INR) have been ordered; report any abnormal values to the health care provider. After the procedure observe the patient for symptoms of bleeding. Monitor the patient's vital signs every 15 minutes (two times), then every 30 minutes (four times), and then every hour (four times). The nurse keeps the patient lying on the right side for at least 2 hours to splint the puncture site. In this position, the liver capsule (a connective tissue layer covering the liver) is compressed against the chest wall, decreasing the risk of hemorrhage or bile leak.

Some pain is common. When leakage involves a large quantity of blood or bile, the peritoneal reaction is great and the resulting pain severe. Assess the patient for pneumothorax (collapsed lung) caused by improper placement of the biopsy needle into the adjacent chest cavity or for bile peritonitis. Immediately report to the health care provider signs and symptoms of pneumothorax such as shortness of breath, change in respiratory and cardiac rate, or decreased breath sounds on the affected side.

Radioisotope Liver Scanning

Rationale

A radioisotope liver scan is a procedure used to outline and detect structural changes of the liver. A radioisotope (also called a radionuclide) is given intravenously. Later, a gamma ray–detecting device (Geiger counter) is passed over the patient's abdomen. This records the distribution of the radioactive particles in the liver. The spleen can also be visualized by the detector when technetium-99m sulfur is used.

Nursing Interventions

The patient is on NPO status from midnight before the test. Assure patients that they will not be exposed to a large amount of radioactivity, since only trace doses of isotopes are used.

Serum Ammonia Test

The normal serum ammonia test value is 10 to 80 mcg/dL.

Rationale

Ammonia is a by-product of protein metabolism. Most of the ammonia is made by bacteria acting on proteins in the intestine. By way of the portal vein, ammonia goes to the liver, where it is normally converted into urea and then excreted by the kidneys. When the patient has severe liver dysfunction or altered blood flow to the liver, ammonia cannot be catabolized, the serum ammonia level rises, and the blood urea nitrogen level decreases. The serum ammonia level is primarily used as an aid in diagnosing hepatic encephalopathy and hepatic coma. Elevated serum ammonia levels suggest liver dysfunction as the cause of these signs and symptoms.

Nursing Interventions

Notify the laboratory of any antibiotics the patient is currently taking. Certain broad-spectrum antibiotics such as neomycin can cause a decreased ammonia level, thus giving inaccurate test results.

Hepatitis Virus Studies

A normal laboratory test result will be negative for hepatitis-associated antigen.

Rationale

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver caused by viruses, bacteria, and noninfectious causes such as alcohol ingestion and drugs. Five viruses, designated A through E, can cause this disease. Hepatitis A, B, and C viruses are the most common hepatitis viruses. Hepatitis D virus is carried by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). Both hepatitis D and E viruses are seen less frequently in the United States than are the hepatitis A, B, or C viruses. The various types of hepatitis virus can be detected by their various antigen and antibody levels, and their different incubation periods must be considered.

Nursing Interventions

Use standard precautions and handle the serum specimen as if it were capable of transmitting viral hepatitis. Don gloves when handling any blood or body fluids, and wash hands carefully after handling equipment.

Serum Amylase Test

The normal serum amylase test value is 60 to 120 Somogyi units/dL, or 30 to 220 units/L (SI units).

Rationale

The serum amylase test can aid in quickly diagnosing pancreatitis in its early stages. Damage to pancreatic cells (as in pancreatitis) or obstruction to the pancreatic ductal flow (as in pancreatic carcinoma) causes an outpouring of this enzyme into the intrapancreatic lymph system and the free peritoneum. Blood vessels draining the free peritoneum and absorbing the lymph pick up this excess amylase. An abnormal rise in the serum level of amylase occurs within 2 hours of the onset of pancreatic disease. Because amylase is rapidly cleared by the kidney, serum levels may return to normal within 36 hours. Persistent pancreatitis, duct obstruction, or pancreatic duct leak (e.g., pseudocysts) cause persistent elevated serum amylase levels.

Nursing Interventions

Note on the laboratory order whether the patient is receiving intravenous dextrose or any medications, since these can cause a false-negative result.

Urine Amylase Test

The normal urine amylase test value is up to 5000 Somogyi units/24 hours, or 6.5 to 48.1 units/hour.

Rationale

Levels of amylase in the urine remain elevated for 7 to 10 days after the onset of pancreatitis. Urine amylase is particularly useful in detecting pancreatitis late in the disease course. This fact is important for diagnosing pancreatitis in patients who have had symptoms for 3 days or longer.

Nursing Interventions

Record the exact time at the beginning and end of the collection period. A 2-hour spot urine or 6-hour, 12-hour, or 24-hour collection can be performed, depending on the health care provider's order. The collection begins after the patient empties the bladder and discards that specimen. All subsequent urine is collected, including the voiding at the end of the collection period. Keep the specimen on ice or refrigerated until it is sent to the laboratory.

Serum Lipase Test

The normal value for serum lipase test results is 10 to 140 units/L.

Rationale

Like serum amylase, serum lipase is elevated in acute pancreatitis and is a helpful complementary test because other disorders (e.g., mumps, cerebral trauma, and renal transplantation) may also cause an increase in serum amylase. Lipase appears in the bloodstream after damage to the pancreas. The lipase levels rise a little later than amylase levels (4 to 48 hours after the onset of pancreatitis), peak around 24 hours, and remain elevated for at least 14 days. Because lipase peaks later and remains elevated longer than amylase, it is more useful in the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis later in the course of the disease.

Nursing Interventions

Instruct the patient to remain on NPO status from midnight, except for water.

Ultrasonography of the Pancreas

Rationale

With the use of reflected sound waves, ultrasonography of the pancreas provides diagnostic information about this inaccessible abdominal organ. Ultrasound examination of the pancreas is used mainly to diagnose carcinoma, pseudocyst, pancreatitis, and pancreatic abscess. Because abnormalities seen on ultrasound persist from several days to weeks, it can support the diagnosis of pancreatitis even after the serum amylase and lipase levels have returned to normal. Furthermore, a follow-up ultrasound study is used to monitor the resolution of pancreatic inflammation and a tumor's response to therapy. A newer procedure using ultrasound is endoscopic ultrasound of the pancreas. In this procedure an ultrasound probe is passed through the patient's mouth and into the small intestine. The sound waves emitted by the probe allow examination of the structures surrounding the pancreas, and also for fine needle biopsy of the pancreas (the needle is passed through the stomach wall to the pancreas) or lesions of the pancreas to differentiate benign lesions from malignancies. The procedure is virtually an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) (see Chapter 5) with a camera. In the event that a lesion is cancerous, this procedure also provides staging of the cancer by visualization via ultrasound of the surrounding structures.

Nursing Interventions

Fluids and food are withheld for 8 hours before the examination. If an endoscopic ultrasound is being performed, the same interventions should be implemented as for an EGD (see Chapter 5). If the patient's abdomen is distended with gas or if the patient has had a recent barium examination, the study should be postponed, since gas and barium interfere with sound wave transmission.

Computed Tomography of the Abdomen

Rationale

A CT scan of the abdomen is a noninvasive, accurate radiographic procedure used to diagnose pathologic pancreatic conditions such as inflammation, tumors, pseudocyst formation, ascites, aneurysms, cirrhosis, abscesses, trauma, cysts, and anatomical abnormalities. The recognizable cross-sectional image produced by a CT scan is especially important for studying the pancreas, since this organ is well hidden by the overlying peritoneal organs.

Nursing Interventions

Fluids and food are withheld from midnight until the examination is complete; however, this test can be performed on an emergency basis on patients who have recently eaten. If possible, show the patient a picture of the machine and encourage the patient to verbalize fears because some patients suffer claustrophobia when enclosed in the machine.

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography of the Pancreatic Duct

Rationale

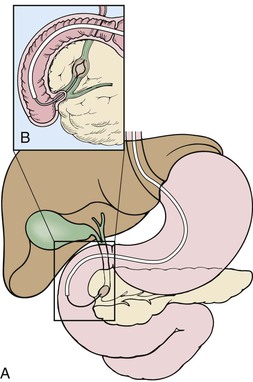

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) enables visualization not only of the biliary system but also of the pancreatic duct. The test involves inserting a fiberoptic duodenoscope through the oral pharynx, through the esophagus and the stomach, and into the duodenum (Figure 45-1). Dye is injected for radiographic visualization of the common bile duct and pancreatic duct. ERCP of the pancreas is a sensitive and reliable procedure for detecting clinically significant degrees of pancreatic dysfunction. It can also be used to evaluate obstructive jaundice, remove common bile duct stones, and place biliary and pancreatic duct stents to bypass obstruction. Localized pancreatic duct narrowing indicates the presence of a tumor. Chronic pancreatitis is demonstrated by multiple areas of ductal narrowing, which can be visualized by ERCP.

Nursing Interventions

Withhold food and fluids for 8 hours before the examination, and obtain the patient's signature on a consent form. Assess prothrombin time and INR before the procedure. Tell patients that the test takes approximately 1 to 2 hours, during which time they must lie completely motionless on a hard x-ray table, which may be uncomfortable. After the procedure, keep the patient on NPO status until the gag reflex returns; assess for abdominal pain, tenderness, and guarding, which could be signs of perforation. Assess for signs and symptoms of pancreatitis (the most common ERCP complication), including increasingly intense abdominal pain, nausea, fever, chills, vomiting, and diminished or absent bowel sounds. Assess for signs of hypovolemic shock, including decreased blood pressure, increased pulse and respirations, shortness of breath, cool and clammy skin, and decreased urine output.

Disorders of the Liver, Biliary Tract, Gallbladder, and Exocrine Pancreas

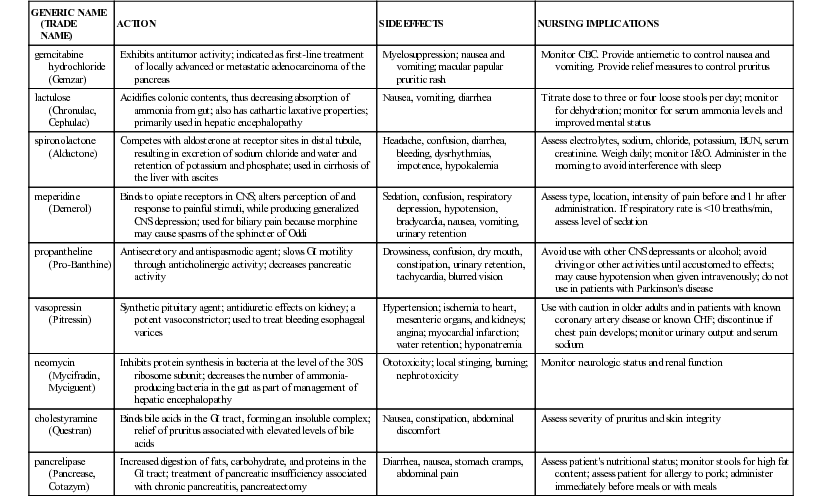

The liver, gallbladder, and exocrine pancreas are all organs that assist with digestion. Review the anatomy and physiology of the accessory organs of digestion (see Chapter 44) and the hepatic portal circulation. Refer to Table 45-1 for medications used for disorders of the accessory organs of digestion.

![]() Table 45-1

Table 45-1

Medications for Disorders of the Gallbladder, Liver, Biliary Tract, and Exocrine Pancreas

| GENERIC NAME (TRADE NAME) | ACTION | SIDE EFFECTS | NURSING IMPLICATIONS |

| gemcitabine hydrochloride (Gemzar) | Exhibits antitumor activity; indicated as first-line treatment of locally advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas | Myelosuppression; nausea and vomiting; macular papular pruritic rash | Monitor CBC. Provide antiemetic to control nausea and vomiting. Provide relief measures to control pruritus |

| lactulose (Chronulac, Cephulac) | Acidifies colonic contents, thus decreasing absorption of ammonia from gut; also has cathartic laxative properties; primarily used in hepatic encephalopathy | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea | Titrate dose to three or four loose stools per day; monitor for dehydration; monitor for serum ammonia levels and improved mental status |

| spironolactone (Aldactone) | Competes with aldosterone at receptor sites in distal tubule, resulting in excretion of sodium chloride and water and retention of potassium and phosphate; used in cirrhosis of the liver with ascites | Headache, confusion, diarrhea, bleeding, dysrhythmias, impotence, hypokalemia | Assess electrolytes, sodium, chloride, potassium, BUN, serum creatinine. Weigh daily; monitor I&O. Administer in the morning to avoid interference with sleep |

| meperidine (Demerol) | Binds to opiate receptors in CNS; alters perception of and response to painful stimuli, while producing generalized CNS depression; used for biliary pain because morphine may cause spasms of the sphincter of Oddi | Sedation, confusion, respiratory depression, hypotension, bradycardia, nausea, vomiting, urinary retention | Assess type, location, intensity of pain before and 1 hr after administration. If respiratory rate is <10 breaths/min, assess level of sedation |

| propantheline (Pro-Banthine) | Antisecretory and antispasmodic agent; slows GI motility through anticholinergic activity; decreases pancreatic activity | Drowsiness, confusion, dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention, tachycardia, blurred vision | Avoid use with other CNS depressants or alcohol; avoid driving or other activities until accustomed to effects; may cause hypotension when given intravenously; do not use in patients with Parkinson's disease |

| vasopressin (Pitressin) | Synthetic pituitary agent; antidiuretic effects on kidney; a potent vasoconstrictor; used to treat bleeding esophageal varices | Hypertension; ischemia to heart, mesenteric organs, and kidneys; angina; myocardial infarction; water retention; hyponatremia | Use with caution in older adults and in patients with known coronary artery disease or known CHF; discontinue if chest pain develops; monitor urinary output and serum sodium |

| neomycin (Mycifradin, Myciguent) | Inhibits protein synthesis in bacteria at the level of the 30S ribosome subunit; decreases the number of ammonia-producing bacteria in the gut as part of management of hepatic encephalopathy | Ototoxicity; local stinging, burning; nephrotoxicity | Monitor neurologic status and renal function |

| cholestyramine (Questran) | Binds bile acids in the GI tract, forming an insoluble complex; relief of pruritus associated with elevated levels of bile acids | Nausea, constipation, abdominal discomfort | Assess severity of pruritus and skin integrity |

| pancrelipase (Pancrease, Cotazym) | Increased digestion of fats, carbohydrate, and proteins in the GI tract; treatment of pancreatic insufficiency associated with chronic pancreatitis, pancreatectomy | Diarrhea, nausea, stomach cramps, abdominal pain | Assess patient's nutritional status; monitor stools for high fat content; assess patient for allergy to pork; administer immediately before meals or with meals |

BUN, Blood urea nitrogen; CBC, complete blood count; CHF, congestive heart failure; CNS, central nervous system; GI, gastrointestinal; I&O, intake and output.

Cirrhosis

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Cirrhosis is a chronic, degenerative disease of the liver in which the lobes become covered with fibrous (scar) tissue, the parenchyma (i.e., the functional tissue of an organ, as opposed to supporting or connective tissue) degenerates, and the lobules are infiltrated with fat. The liver tries unsuccessfully to regenerate and, as a result, forms abnormal blood vessels and biliary duct abnormalities (Lewis et al., 2011). The overgrowth of new and fibrous tissue restricts the flow of blood to the organ, which contributes to its destruction. Hepatomegaly (enlargement of the liver) and liver contraction (occurs later in the disease) cause loss of the organ's function.

Cirrhosis is ranked as the twelfth leading cause of death in the United States. Approximately 27,000 people die each year from the disease. Slightly more men are diagnosed with cirrhosis than women, with over 100,000 people having the disease (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2013).

There are several forms of cirrhosis, caused by different factors. Alcohol-related liver disease may occur with heavy alcohol consumption. The amount of alcohol that causes damage to the liver differs among individuals. The chances for developing alcohol-related cirrhosis increase for women when they ingest more than two or three alcoholic drinks per day, and for men when they drink three or four drinks per day. Postnecrotic cirrhosis, found worldwide, is caused by viral hepatitis (especially hepatitis C, but also hepatitis B and D), exposure to hepatotoxins (e.g., industrial chemicals), or infection. Primary biliary cirrhosis occurs more often in women and results from destruction of the bile ducts due to inflammation. The resulting damage to the ducts leads to bile backing up into the liver. Secondary biliary cirrhosis is caused by chronic biliary tree obstruction from gallstones, chronic pancreatitis, a tumor, cystic fibrosis, or biliary atresia (the absence of or underdevelopment of biliary structures that is congenital in nature) in children. Cardiac cirrhosis results from longstanding, severe right-sided heart failure in patients with cor pulmonale, constrictive pericarditis, and tricuspid insufficiency. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) results from fat building up in the liver. The incidence of NAFLD is on the increase as a result of the growing obesity population. NAFLD is also associated with diabetes, coronary artery disease, and use of corticosteroids.

The cause of cirrhosis is not always known. Alcoholism is by far the greatest factor leading to cirrhosis. It is believed to result from the combination of alcohol's hepatotoxic effect on the liver coupled with the common problem of protein malnutrition seen in alcoholics. Cirrhosis of the liver from severe malnutrition without alcoholism has also occurred. Patients with a diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B and C have a 10% to 20% chance of developing cirrhosis of the liver (Lewis et al., 2011).

With repeated insults, the liver progresses through the following stages: destruction, inflammation, fibrotic regeneration, and hepatic insufficiency. Although liver cells have great potential for regeneration, repeated scarring decreases their ability to replace themselves. As the blood supply continues to diminish and scar tissue increases, the organ atrophies.

Functions of the liver are altered in several ways. The liver's ability to synthesize albumin is reduced as a result of liver cell damage. Obstruction of the portal vein as it enters the liver results in portal hypertension—increased venous pressure in the portal circulation caused by compression or occlusion of the portal or hepatic vascular system. In most instances, portal hypertension that is caused by cirrhosis is irreversible.

This increased pressure causes ascites (an accumulation of fluid and albumin in the peritoneal cavity). The damaged liver cannot metabolize protein in the usual manner; therefore protein intake may result in an elevation of blood ammonia levels. Reduced synthesis of protein and the leaking of existing protein result in hypoalbuminemia (reduced protein or albumin level in the blood), which reduces the blood's ability to regain fluids through osmosis. Protein must be present in adequate amounts to create colloidal osmotic pressure and “attract” the fluid to pass back into the blood vessels after it escapes in the capillaries. As fluid leaves the blood and the circulating volume decreases, the receptors in the brain signal the adrenal cortex to increase secretion of aldosterone to stimulate the kidneys to retain sodium and water. The normal liver inactivates the hormone aldosterone, but the damaged liver allows its effect to continue (hyperaldosteronism). Retention of fluid and sodium results in increased pressure in blood vessels and lymphatic channels, resulting in portal hypertension. Ascites is thus a result of portal hypertension, hypoalbuminemia, and hyperaldosteronism.

Hepatic insufficiency gradually causes distention of veins in the upper part of the body, including the esophageal vein. Esophageal varices develop and may rupture, causing severe hemorrhage.

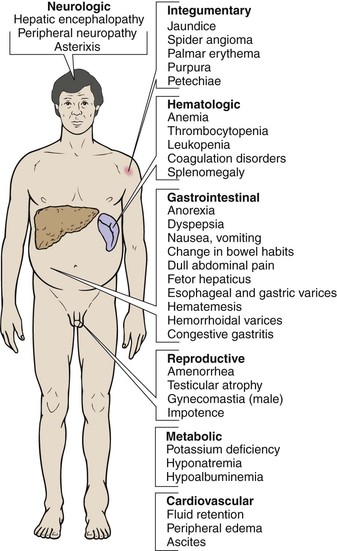

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations of cirrhosis of the liver differ, depending on the stage of the disease. In the early stages the liver is firm and therefore easier to palpate, and abdominal pain may be present because rapid enlargement produces tension on the organ's fibrous covering. Later stages of the disease are characterized by dyspepsia, changes in bowel habits, gradual weight loss, ascites, enlarged spleen, malaise, nausea, jaundice, ecchymoses, and spider telangiectases (small, dilated blood vessels with a bright red center point and spiderlike branches). Spider telangiectases occur on the nose, cheeks, upper trunk, neck, and shoulders. These later manifestations are the result of scarring of liver tissue that produces chronic failure of liver function and also fibrotic changes that cause obstruction of the portal circulation.

When enough cells of the liver become involved to interfere with its function and obstruct its circulation, the GI organs and the spleen become congested and cannot function properly. Anemia occurs because of the body's decreased ability to produce red blood cells (RBCs). The cirrhotic liver cannot absorb vitamin K or produce the clotting factors VII, IX, and X. These factors cause the patient with cirrhosis to develop bleeding tendencies.

Assessment

Subjective data in the early stages include the patient's description of flulike symptoms (loss of appetite, nausea and vomiting, general weakness, and fatigue), indigestion, abnormal bowel function (either constipation or diarrhea), flatulence, and abdominal discomfort. The anatomical area most commonly affected is in the epigastric region or the right upper quadrant of the abdomen.

Subjective data in the later stages typically include the same early-stage symptoms, but now more intense in the later stages. The patient may complain of dyspnea, pruritus, and severe fatigue that interfere with the ability to carry out routine activities. Pruritus results from an accumulation of bile salts under the skin, the result of jaundice.

Collection of objective data in the early stages includes observing low hemoglobin, fever, weight loss, and jaundice (yellow discoloration of the skin, mucous membranes, and sclerae of the eyes [scleral icterus], caused by greater than normal amounts of bilirubin in the serum). Collection of objective data in the later stages includes noting epistaxis, purpura, hematuria, spider angiomas (telangiectases), and bleeding gums. Late symptoms include ascites, hematologic disorders, splenic enlargement, and hemorrhage from esophageal varices or other distended GI veins. The patient may also appear mentally disoriented and display abnormal behaviors and speech patterns due to increased ammonia levels in the brain. Any prolonged interference with gas exchange leads to hypoxia, coma, and ultimately death.

Diagnostic Tests

Many diagnostic tests aid in the diagnosis of cirrhosis. Poor liver function may be manifested as abnormal electrolyte values; elevated serum bilirubin, AST, ALT, LDH, and GTT; decreased total protein and serum albumin; elevated ammonia; low blood glucose (hypoglycemia) from impaired gluconeogenesis; prolonged prothrombin time; increased INR; and decreased cholesterol levels. Visualization through ERCP (to detect common bile duct obstruction), esophagoscopy with barium esophagography to visualize esophageal varices, scans and biopsy of the liver, and ultrasonography are used to diagnose cirrhosis. Paracentesis (a procedure in which fluid is withdrawn from the abdominal cavity) relieves ascites and also provides fluid for laboratory examination.

Medical Management

When possible causes have been identified, the initial treatment is to eliminate those causes, decrease the buildup of fluids in the body, prevent further damage to the liver, and provide individual supportive care. Eliminating alcohol, hepatotoxins (e.g., acetaminophen [Tylenol]), or environmental exposure to harmful chemicals is essential to prevent further damage to the liver. Diet therapy is aimed at correcting malnutrition, promoting the regeneration of functional liver tissue, and compensating for the liver's inability to store vitamins, while avoiding fluid retention and hepatic encephalopathy. A diet that is well balanced, high in calories (2500 to 3000 calories/day), moderately high in protein (75 g of high-quality protein per day), low in fat, low in sodium (1000 to 2000 mg/day), and with additional vitamins and folic acid will usually meet the needs of the patient with cirrhosis and improve deficiencies. A protein-restricted diet may be prescribed for a patient recovering from an acute episode of hepatic encephalopathy.

Antiemetics may be prescribed to control nausea or vomiting. Monitor the patient closely for toxicity, which develops quickly when the poorly functioning liver cannot clear these drugs from the system. Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) or dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) may be given, whereas prochlorperazine maleate (Compazine), hydroxyzine pamoate (Vistaril), or hydroxyzine hydrochloride (Atarax) are contraindicated in severe liver dysfunction.

Later manifestations may be severe and result from liver failure and portal hypertension. Jaundice, peripheral edema, esophageal varices, hepatic encephalopathy, and ascites develop gradually (Figure 45-2).

Complications and treatment.

The severity of fluid retention from ascites and edema determines the treatment. Initially the patient is placed on bed rest with accurate monitoring of intake and output (I&O). Restrictions are placed on the amount of fluid (500 to 1000 mL/day) and sodium (1000 to 2000 mg/day). Diuretic therapy may be added if the diet does not control the ascites and edema. Spironolactone (Aldactone) at 300 to 1000 mg/day may be used to obtain the desired diuresis. Other diuretics may be added, including furosemide (Lasix) or hydrochlorothiazide (HydroDIURIL). Vitamin supplements include vitamin K, vitamin C, and folic acid. Salt-poor albumin may be administered in an attempt to restore plasma volume if the intravascular volume is decreased significantly. Complications of diuretic therapy include plasma volume deficit, decreased renal function, and electrolyte imbalance.

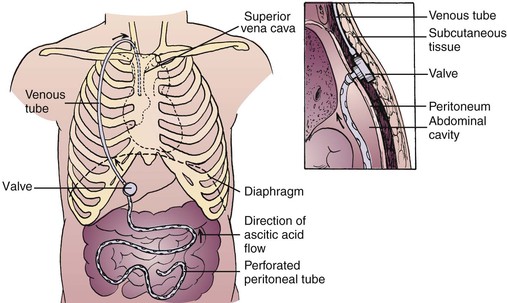

Another method of treatment for ascites and edema is the LeVeen continuous peritoneal jugular shunt (Figure 45-3). This procedure allows the continuous shunting of ascitic fluid from the abdominal cavity through a one-way, pressure-sensitive valve into a silicone tube that empties into the superior vena cava. Patients with this shunt are monitored for complications, which include congestive heart failure, leakage of ascitic fluid, infection at the insertion sites, peritonitis, septicemia, and shunt thrombosis.

Paracentesis (see Chapter 15), in which fluid is removed from the abdominal cavity by either gravity or vacuum, provides temporary relief from ascites. It is imperative that patients urinate immediately before the procedure to prevent puncture of the bladder. The patient should sit on the side of the bed or be placed in a high Fowler's position. An incision is made in the skin, and a hollow trocar, cannula, or catheter is passed through the incision and into the cavity. The fluid is removed over a period of 30 to 90 minutes to prevent sudden changes in blood pressure, which could lead to syncope. Monitor the patient closely for signs of hypovolemia and electrolyte imbalances. Apply a dressing over the insertion site, and observe for bleeding and drainage.

Esophageal varices (a complex of longitudinal, tortuous veins at the lower end of the esophagus) enlarge and become edematous as the result of portal hypertension. They are susceptible to ulceration and hemorrhage; avoiding this is a main goal of treatment. For patients who have not bled from esophageal varices, prophylactic treatment with nonselective beta blockers (e.g., propranolol [Inderal]) has been shown to reduce the risk of bleeding and bleeding-related deaths. Varices can rupture as a result of anything that increases abdominal venous pressure, such as coughing, sneezing, vomiting, or the Valsalva maneuver. Rupture may occur slowly over several days or suddenly and without pain. An endoscopy may be performed to identify varices or to rule out bleeding from other sources. Endoscopic therapies include sclerotherapy (the injection of chemicals used to cause inflammation, followed by fibrosis and destruction of the vessels causing the bleeding) and ligation of varices.

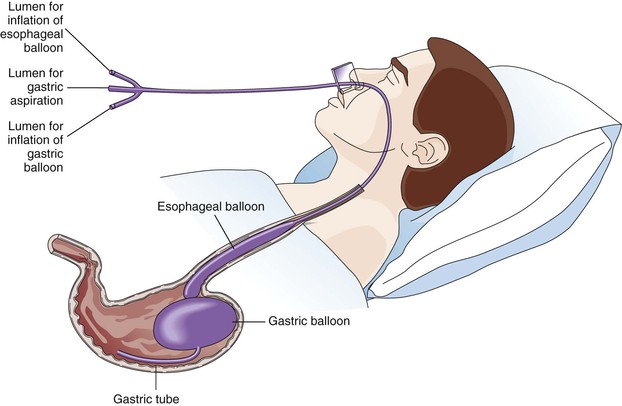

Therapeutic management of a ruptured esophageal varix is a medical emergency. The patient's airway must be maintained, the bleeding varix controlled, and IV lines established for fluids and blood replacement as needed. The hormone vasopressin (VP), administered intravenously or directly into the superior vena cava, is used to decrease or stop the hemorrhaging. VP produces vasoconstriction of the vessels, decreases portal blood flow, and decreases portal hypertension. Current drug therapy in some institutions is a combination of VP and nitroglycerin (NTG). NTG reduces the detrimental effects of VP, which include decreased coronary blood flow and increased blood pressure. VP should be avoided or used cautiously in the older adult because of the risk of cardiac ischemia (i.e., a restriction in blood supply to the heart). If the VP drip does not stop or control bleeding, a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube with openings at the tip may be inserted. This triple-lumen tube has a lumen for inflating the esophageal balloon, one for inflating the gastric balloon, and one for gastric lavage (Figure 45-4). The tube is passed through the nose, and the balloon in the stomach, the one in the esophagus, or both are inflated to press against the bleeding vessels and control the hemorrhage. The gastric aspiration is attached to low, intermittent suction. When either balloon is inflated, a Levin tube is passed into the esophagus through the mouth and attached to low suction to drain the saliva that cannot drain into the stomach. The balloon must be deflated periodically to prevent necrosis. Give the patient nothing by mouth and elevate the head of the bed 30 to 45 degrees to help prevent aspiration of stomach contents and help the patient breathe.

Gastric lavage is performed to remove any swallowed blood from the stomach. Some facilities use iced isotonic saline solutions for the lavage to facilitate vasoconstriction. Endoscopic sclerotherapy may also be used to control the bleeding.

Other methods used to treat bleeding esophageal varices include band ligation. In this procedure an endoscope is passed into the esophagus and elastic bands are placed to tie off bleeding vessels. This procedure is also performed to prevent esophageal varices from bleeding. Band ligation has a small risk of causing scarring of the esophagus. The medication octreotide (Sandostatin) is sometimes used in combination with band ligation when treating bleeding varices. Octreotide (Sandostatin) slows the flow of blood from internal organs to the portal vein. This helps to reduce pressure in the portal vein and is administered for 5 days following an esophageal hemorrhage (Mayo Clinic, 2013).

Patients suffering from portal hypertension and esophageal varices may benefit from surgical shunting procedures that divert blood from the portal system to the venous system. The portacaval shunt diverts blood from the portal vein to the inferior vena cava. The splenorenal shunt requires the removal of the spleen, and the splenic vein is anastomosed to the left renal vein. The mesocaval shunt involves anastomosis of the superior mesenteric vein to the inferior vena cava. These procedures are associated with a high mortality rate. They may be performed in an emergency to control acute esophageal varix bleeding or in a therapeutic situation when a patient has already bled. Complications of surgical shunting procedures are hepatic encephalopathy, GI bleeding, ascites, and liver failure.

Care of the patient who has hemorrhaged from an esophageal varix includes maintenance of oxygen content levels within the blood and administration of fresh frozen plasma and packed RBCs, vitamin K (AquaMEPHYTON), histamine (H2) receptor blockers such as cimetidine (Tagamet), and electrolyte replacements as needed without fluid overload. Ammonia buildup is avoided with the use of cathartics (e.g., lactulose [Chronulac]) and neomycin. Preventing ammonia buildup keeps hepatic encephalopathy from occurring.

Hepatic encephalopathy is a type of brain damage caused by liver disease and consequent ammonia intoxication. It is thought to result from a damaged liver being unable to metabolize substances that can be toxic to the brain, such as ammonia. The patient's signs and symptoms progress from inappropriate behavior, disorientation, asterixis, and twitching of the extremities to stupor and coma. Asterixis is a hand-flapping tremor in which the patient stretches out an arm and hyperextends the wrist with the fingers separated, relaxed, and extended. A rapid, irregular flexion and extension (flapping) of the wrist occurs in the patient who is acutely ill. Treatment of the patient with hepatic encephalopathy consists of supportive care to prevent further damage to the liver.

In the past, a low-protein diet was often prescribed for patients with cirrhosis of the liver. Restricting protein intake was thought to decrease the amount of ammonia produced in the intestine, thus preventing hepatic encephalopathy. It is now believed that protein should not be restricted because these patients often have existing malnutrition. On occasion, protein is decreased in the diet of a patient with an exacerbation of hepatic encephalopathy. In addition, carbohydrates are necessary for the patient with cirrhosis. To provide extra calories, a protein-free supplement such as glucose polymer (Polycose) can be used during an exacerbation of hepatic encephalopathy. Other supplemental enteral formulas containing amino acid and calorie supplementation may be given to the patient who has protein-calorie malnutrition (Lewis et al., 2011).

Teach the patient to avoid potentially hepatotoxic over-the-counter drugs such as acetaminophen and to abstain from alcohol. Medications may be given to cleanse the bowel and help decrease the serum ammonia level. Lactulose decreases the bowel's pH from 7 to 5, thus decreasing the production of ammonia by bacteria within the bowel. Lactulose may be administered orally, as a retention enema, or via nasogastric (NG) tube. It also functions as a cathartic. The lactulose traps ammonia in the gut, and the drug's laxative effect expels the ammonia from the colon. Antibiotics such as neomycin, which are poorly absorbed from the GI tract, are given orally or rectally. They reduce the bacterial flora of the colon. Bacterial action on protein in feces results in ammonia production. Because neomycin may cause renal toxicity and hearing impairment, lactulose is frequently preferred.

Nursing Interventions and Patient Teaching

Check vital signs every 4 hours, or more often if evidence of hemorrhage is present. Observe the patient for GI hemorrhage as evidenced by hematemesis, melena, anxiety, and restlessness.

Most patients require a well-balanced, moderate, high-protein, high-carbohydrate diet with adequate vitamins. With impending liver failure, protein and fluids are restricted. Sodium restriction is frequently necessary, which can make providing a palatable diet more difficult. Provide frequent oral hygiene and a pleasant environment to help the patient increase food intake.

A major nursing focus for many patients is to help them deal with alcoholism. This requires establishing trust that the health team is interested in the patient's well-being. Patients must admit that they have a drinking problem before they can be helped. Provide information regarding community support programs, such as Alcoholics Anonymous, for help with alcohol abuse.

Because of pruritus, malnutrition, and edema, the patient with cirrhosis is prone to skin lesions and pressure sores. Initiate preventive nursing interventions to avoid impairment of skin integrity, such as an alternating pressure air mattress, frequent turning, and back rubs. Apply soothing lotion to relieve pruritus.

Observe the patient's mental status and report changes such as disorientation, headache, or lethargy. Assist in activities of daily living (ADLs) as needed to promote good hygiene while allowing the patient to conserve energy. Observe for edema by measuring ankles daily, and observe for ascites by measuring abdominal girth. Record accurate I&O and daily weight. Nursing intervention with concern and warmth regardless of physical changes is essential in helping the patient maintain self-esteem.

Refer to Nursing Care Plan 45-1 for a sample nursing care plan for the patient with cirrhosis of the liver. The patient with cirrhosis must understand the need for getting adequate rest and avoiding infections. Plan activity around complete bed rest until strength is regained. Turning the patient at least every 2 hours and providing range-of-motion exercises will help avoid infection and prevent thrombophlebitis. Instruct the patient to use a soft-bristled toothbrush, use an electric razor, blow the nose cautiously, and avoid straining at stools to prevent bleeding as a result of a lack of vitamin K and certain clotting factors. Avoid soap, perfumed lotion, and rubbing alcohol because they will further dry the skin. For pruritus and dry skin, administer diphenhydramine (Benadryl). Explain the relationship of the therapeutic diet to the diagnosis and the liver's ability to function.

Help the patient and family identify community resources for home health care and alcohol rehabilitation to assist them in dealing with problems that arise after discharge. Because of the seriousness of the disease, the patient and the family need understanding and support throughout the treatment (see Home Care Considerations box).

Prognosis.

Cirrhosis of the liver cannot be cured; the patient's prognosis depends on many factors. If the cause of the liver damage can be treated or eliminated, the prognosis improves. Discontinuing the drinking of alcohol, and treating the hepatitis, help to slow and even stop the progression of cirrhosis. The patient's adherence to prescribed treatment will also be a determining factor in the prognosis. Liver transplantation is an option for some patients, but this depends on many factors, including the cause of the cirrhosis and the patient's overall health status.

Liver Cancer

Etiology and Pathophysiology

It is estimated that primary liver cancer will be diagnosed in more than 30,000 people in the year 2013 (over 22,000 men and nearly 8,000 women). Of these newly diagnosed cases it is estimated that over 21,000 will die of the disease. The type of primary liver cancer seen most frequently is hepatocellular carcinoma; the other primary tumors are cholangiomas or biliary duct carcinomas. Cirrhosis of the liver and infection with hepatitis C or hepatitis B are high-risk factors for primary liver cancer. The increase in cases of primary liver cancer stems from the increased incidence of hepatitis C. In the United States, liver cancer usually occurs in people over 45 years of age. The average age at diagnosis is 62 years.

Metastatic carcinoma of the liver, or secondary liver cancer, occurs more often than primary liver cancer (American Cancer Society [ACS], 2013a). The high rate of blood flow through the portal vein and its massive capillary structure make the metastasis of cancer cells to the liver more likely than to other organs. The pancreas, colon, stomach, breast, and lung are common primary sites of cancer that metastasizes to the liver.

Clinical Manifestations and Diagnostic Tests

Diagnosing carcinoma of the liver is difficult. In its early stages many of the clinical manifestations (e.g., hepatomegaly, weight loss, peripheral edema, ascites, portal hypertension) are similar to those of cirrhosis of the liver. Other common manifestations include dull abdominal pain in the epigastric or right upper quadrant region, jaundice, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, and extreme weakness. Palpation may reveal an enlarged, nodular liver. Patients frequently have pulmonary emboli. Tests to assist in the diagnosis are a liver scan, ultrasound, CT scan, magnetic resonance imaging, hepatic arteriography, ERCP, and needle liver biopsy. The test for alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) may be positive in hepatocellular carcinoma. AFP helps distinguish primary cancer from metastatic cancer (ACS, 2013a).

Medical Management and Nursing Interventions

Treatment of cancer of the liver is largely palliative. Surgical excision (lobectomy) is sometimes performed if the tumor is localized to one portion of the liver. Only a small percentage of patients have surgically resectable disease; usually the cancer is too advanced for surgery when it is detected. Surgical excision or transplantation offers the only chance for cure. Medical management is similar to that for cirrhosis of the liver. Chemotherapy may be used, but the response is usually poor. Portal vein or hepatic artery perfusion with chemotherapy agents such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) may be attempted.

Nursing interventions for the patient with liver carcinoma focus on keeping the patient as comfortable as possible. Because the problems are the same as with advanced liver disease, the nursing interventions discussed for cirrhosis of the liver apply.

Prognosis

The 5-year survival rate for liver cancer depends on the extent of the cancer when it is diagnosed. For early-stage (i.e., small) tumors that can be resected surgically the 5-year survival rate is 50% if the patient has no other serious health problems. Unfortunately, since many liver cancers are not discovered until late in the disease process the 5-year survival rate for all stages combined is less than 15% (ACS, 2013a).

Hepatitis

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver resulting from several types of viral agents or exposure to toxic substances. Rarely, hepatitis is caused by bacteria, such as streptococci, salmonellae, or Escherichia coli.

The five major types of viral hepatitis are caused by distinct but similar viruses that produce almost identical signs and symptoms but vary in their incubation period, mode of transmission, and prognosis. Hepatitis A (formerly called infectious hepatitis) is the most common form today and is a short-incubation virus (10 to 40 days). Hepatitis B (formerly called serum hepatitis) is a long-incubation virus (28 to 160 days). Hepatitis C has an incubation period of 2 weeks to 6 months (commonly 6 to 9 weeks). Hepatitis D (also called delta virus) causes hepatitis as a coinfection with hepatitis B and may progress to cirrhosis and chronic hepatitis. The incubation period is 2 to 10 weeks. Hepatitis E (also called enteric non-A–non-B hepatitis) is transmitted through fecal contamination of water, primarily in developing countries. It is rare in the United States. The incubation period is 15 to 64 days. Recently, hepatitis G virus has been discovered. Hepatitis G virus has been found in blood donors and can be transmitted by transfusion. It frequently coexists with other hepatitis viruses, such as hepatitis C.

Health officials are required by law to report all cases of viral hepatitis to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia. Modes of transmission for the various types of hepatitis are listed in Box 45-1.

The basic pathologic findings in the six forms of viral hepatitis are identical. A diffuse inflammatory reaction occurs, liver cells begin to degenerate and die, and the liver's normal functions slow down. The outcome may be affected by the virulence of the virus, the liver's preexisting condition, the health care given when the disease is diagnosed, and patient compliance with treatment.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations for viral hepatitis vary greatly; some patients are asymptomatic, whereas others develop hepatic failure or hepatic encephalopathy.

Assessment

Subjective data include patients' reports of general malaise, aching muscles, photophobia, lassitude, headaches, and chills. Abdominal pain, dyspepsia, nausea, diarrhea, and constipation are reported also. The patient may complain of pruritus from the buildup of bile salts in the skin. The patient complains of tenderness in the liver and remains fatigued for several weeks.

Collection of objective data includes observing hepatomegaly, enlarged lymph nodes, and weight loss. Jaundice appears because of the damaged liver's inability to metabolize bilirubin; the resultant signs are yellowish skin; discoloration of the sclera (scleral icterus) and mucous membranes; dark, tea-colored urine; and clay-colored stools. Relapses are common in the convalescent stage.

Diagnostic Tests

Changes in the liver caused by viral hepatitis result in elevated direct bilirubin, GGT, AST, ALT, LDH, and alkaline phosphatase levels; a prolonged prothrombin time and increased INR; and, in severe hepatitis, decreased serum albumin. Leukopenia (low white blood cell count) is common in these patients, followed by lymphocytosis (high white blood cell count). Hypoglycemia is present in approximately 50% of patients with hepatitis. Serum is examined for the presence of antigens associated with hepatitis A, B, C, D, or G. A CT scan of the abdomen reveals hepatomegaly.

Medical Management

Providing supportive therapy for existing signs and symptoms and preventing transmission of the disease are important aspects of treatment of the patient with viral hepatitis. Hospitalization is an option for patients whose bilirubin concentrations in the blood are more than 10 mg/dL and for those with a prolonged prothrombin time and increased INR, but usually patients are cared for at home. Bed rest for several weeks is commonly prescribed.

Drug therapy for chronic hepatitis B focuses on decreasing the viral load, decreasing the rate of disease progression, and monitoring for detection of drug-resistant HBV. At present, several drugs are useful in suppressing viral activity and decreasing viral load in patients with HBV. The percentage of patients seroconverting (developing antibodies against the virus) remains relatively low. Lamivudine (Epivir, 3TC), interferon-beta, and adefovir dipivoxil (Hepsera) are three drugs being used in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Telbivudine (Tyzeka) is a new drug used to treat chronic HBV infection. Telbivudine has been shown to decrease the viral load more effectively than lamivudine and adefovir (www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HBV/HBVfaq.htm#treatment). Patients should be informed of the possibility of serious or life-threatening liver damage. Lactic acidosis (buildup of acid in the blood) can occur with the use of some of these newer drugs used to treat HBV (National Library of Medicine [NLM], 2010).

In chronic hepatitis C, drug therapy is also directed at reducing the viral load, decreasing progression of the disease, and promoting seroconversion. Treatment options for HCV are interferon alfa-2b (Intron A), ribavirin (Rebetol), and pegylated interferon alfa-2a (Pegasys). This combination therapy eradicates the virus more effectively than monotherapy. Another treatment option is liver transplantation. In fact, half of all liver recipients are HCV positive. Most transplanted livers eventually become infected with HCV, but recipients can increase both quantity and quality of life by avoiding risky behaviors (CDC, 2012).

The patient is not allowed alcohol for at least 1 year and may need supportive care from the community to comply. Most patients tolerate small, frequent meals of a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet. If the patient is dehydrated, IV fluids are given with addition of vitamin C for healing, vitamin B complex to assist the damaged liver's inability to absorb fat-soluble vitamins, and vitamin K to combat prolonged coagulation time. Avoid all unnecessary medications, particularly sedatives.

Give gamma globulin or immune serum globulin as soon as possible to people who have been in direct contact with a person with hepatitis A during the infectious period (2 weeks before and 1 week after onset of symptoms). A dose of 0.02 mL/kg of body weight, given intramuscularly, is effective in preventing hepatitis A in 80% to 90% of cases. At present, three vaccines are used to prevent hepatitis A: Havrix, Vaqta, and Avaxim.

Primary immunization consists of a single dose administered intramuscularly in the deltoid muscle. A booster is recommended between 6 and 12 months after the primary dose to ensure adequate antibody titers and long-term protection. However, primary immunization provides immunity within 30 days after a single dose.

Until routine vaccination of children is feasible, people who are at risk for infection should be vaccinated for hepatitis A. This includes people traveling to countries where hepatitis A is endemic; sexually active homosexual and bisexual men; patients with chronic liver disease; injecting drug users; and people at risk for occupational infection, such as those who work with hepatitis A in research laboratory settings.

Individuals who have been exposed to HBV via a needle puncture or sexual contact should be protected with hepatitis B immune globulin. A dose is administered intramuscularly as quickly after exposure as possible. This dose is repeated 1 month later. People identified as being at high risk for developing hepatitis B should be vaccinated if they are not already immune. These people include the following:

• All health care personnel (especially emergency department, operating room, intensive care unit [ICU], and dialysis personnel; phlebotomists; and laboratory technicians)

• People with high-risk lifestyles (drug users, tattoo recipients, homosexual men, and prostitutes)

• Infants born to mothers who test positive for hepatitis B surface antigen

The CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (2009) recommends making hepatitis B vaccine a part of routine vaccination schedules for all newborns and adolescents. The protection program consists of three vaccinations: an initial vaccination, a vaccination 1 month later, and a third vaccination 6 months after the first injection. The hepatitis B vaccine has been shown to provide protection for 3 to 5 years in approximately 90% of the people treated. It is hoped that universal vaccination will lead to eventual prevention and control of hepatitis B.

Hepatitis B, C, D, and G are spread through blood transfusions. The blood used should be screened for elevated ALT and anti–hepatitis B core, and for anti–hepatitis C, anti–hepatitis D, and anti–hepatitis G antigens.

Liver transplantation.

Liver transplantation has become a practical therapeutic option for many people with end-stage liver disease, generally improving their quality of life. Indications for liver transplantation include congenital biliary abnormalities, inborn errors of metabolism, hepatic malignancy (confined to the liver), sclerosing cholangitis, and chronic end-stage liver disease. Liver disease related to chronic viral hepatitis is the leading indication for liver transplantation. Liver transplants are not recommended for patients with widespread malignant disease. There are approximately 16,000 people waiting for liver transplants. At present, only approximately 6000 transplants are performed annually (American Liver Foundation, 2012).

The major postoperative complications are rejection and infection. Liver transplant candidates must go through a rigorous presurgery screening. However, the liver seems to be less susceptible to rejection than the kidney.

The source of a liver used for transplantation may be a deceased donor or a live donor. The live donor donates only a portion of his or her liver to the recipient. Within weeks the recipient and the donor's liver will grow to the size the body needs. The donor faces potential risks, such as liver and biliary problems, postoperative infection, and other common postoperative complications (see Chapter 41).

The most common complications for the recipient of a liver transplant include rejection of the new liver tissue and infection. The use of cyclosporine, an effective immunosuppressant drug, has been a major factor in improving the success rate of liver transplantation. It does not cause bone marrow suppression and does not impede wound healing. Other immunosuppressants used include azathioprine (Imuran), corticosteroids, tacrolimus (Prograf), and mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept). New agents, including the interleukin-2 receptor antagonists basiliximab (Simulect) and daclizumab (Zenapax), are being used in combination with other immunosuppressive agents to reduce rejection. Other factors in the improved success rate are advances in surgical techniques, better selection of potential recipients, and improved management of the underlying liver disease before surgery.

Patients who have liver disease secondary to viral hepatitis often experience reinfection of the transplanted liver with hepatitis B or C. HCV recurrence as evidenced by histologic damage is almost universal after transplantation. Approximately 20% to 30% of patients develop cirrhosis of the transplanted liver by the fifth year posttransplantation. Antiviral therapy for HCV initiated posttransplantation, even before the development of histologic evidence of recurrence, has failed to alter this recurrence pattern. Approximately 75% of patients survive more than 5 years following transplantation (American Liver Foundation, 2012).

Nursing Interventions and Patient Teaching

The patient who has a liver transplant requires competent and highly skilled nursing interventions, in either an ICU or another specialized unit. Postoperative nursing care includes assessing neurologic status; monitoring for signs of hemorrhage; preventing pulmonary complications; monitoring drainage, electrolyte levels, and urinary output; and monitoring for signs and symptoms of infection and rejection. Common respiratory problems include pneumonia, atelectasis (collapsed lung), and pleural effusions. Have the patient use measures such as coughing, deep breathing, incentive spirometry, and repositioning to prevent these complications. Measure and record drainage from the Jackson-Pratt drain, NG tube suctioning, and T-tube, and note the color and consistency of drainage. A critical aspect of nursing interventions after liver transplantation is monitoring for infection. The first 2 months after the surgery are critical. Infection can be viral, fungal, or bacterial. Fever may be the only sign of infection. Emotional support and teaching the patient and family are essential.

The care of the patient with viral hepatitis includes ensuring rest, maintaining adequate nutrition, providing adequate fluids, and caring for the skin. The care of the patient with hepatitis continues over time, and support and patient education are necessary throughout the entire illness.

Preventing transmission of the disease is of primary importance in caring for the patient with viral hepatitis. The patient, family, and health care providers must be knowledgeable about routes of transmission of the virus and take steps to avoid such transmission. Proper personal hygiene and good sanitation, as well as hepatitis A vaccination, will help prevent the spread of hepatitis A. Give patients a thorough explanation of the reasons for the precautions, and instruct them in the proper handling of their own secretions and body wastes and in thorough methods of hand hygiene. Wear gown and gloves when handling excreta, giving enemas, taking rectal temperatures, handling food waste, handling needles, disposing of urine, or carrying out any other procedure or hygiene measure that involves direct contact with the patient's body fluids.

Not all patients know they are infected with hepatitis, so following standard precautions with all patients prevents the spread of all blood-borne pathogenic diseases. Health care personnel should always take the utmost care in handling syringes, needles, and other instruments that are contaminated with the patient's serum. Maintaining standard precautions while exposed to blood and body fluids such as saliva, semen, and vaginal secretions is essential to prevent the transmission of hepatitis B. Appropriate transmission-based precautions should be followed as designated by facility policy. Use enteric precautions for 7 days after the onset of hepatitis A. Use standard precautions for all patients.

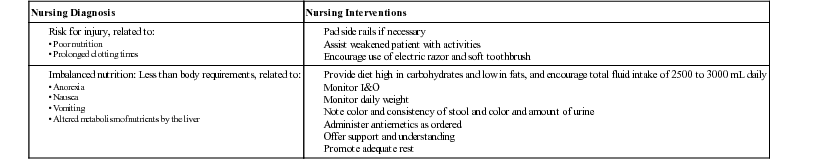

Nursing diagnoses and interventions for the patient with hepatitis include but are not limited to the following.

| Nursing Diagnosis | Nursing Interventions |

For the patient with viral hepatitis being cared for at home, teach the family necessary precautions. Patients should avoid sexual activity during the acute stage of hepatitis B, C, and D. Sexual precautions should be taken, and needles and razors should not be shared. Patients with hepatitis A must wash their hands thoroughly after toileting, must disinfect feces-soiled articles (boil for 1 minute), and must not prepare foods for others while symptomatic. If possible, the patient should use separate bathroom facilities. Personal care items and drinking glasses should not be shared. The patient's clothes should be laundered separately in hot water. Contaminated items should be disposed of properly. Sexual intercourse should be avoided while in the acute stage of hepatitis A.

Inform the patient and family about signs and symptoms associated with hepatitis, including light-colored stools, dark-colored urine, jaundice, fever, GI disturbances, unusual bleeding that might be indicative of a prolonged prothrombin time and increased INR, and tenderness or pain in the abdomen. The danger of alcohol use and its effect on the liver should be clearly understood.

Prognosis

The prognosis for the patient with hepatitis differs, depending on the causative agent. Recovery from hepatitis A is high, since the virus does not remain in the body after the infection has resolved. Within 3 months after diagnosis over 85% recover and nearly all recover within 6 months. The mortality rate for hepatitis A is 0.5% (CDC, n.d., National Institutes of Health, n.d.). The acute stage of the illness typically lasts up to 3 weeks, and it is usually 4 to 6 months before the liver returns to normal function. A small percentage of patients will develop chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis as a result of hepatitis B infection. Patients who do develop chronic hepatitis are at a higher risk for liver cancer. Approximately 1 in 100 people with hepatitis B die. Hepatitis C often progresses to chronic hepatitis. Approximately 75% to 85% of patients who acquire HCV go on to develop chronic infection. Cirrhosis develops in 5% to 20% of those infected. One to five percent of patients with hepatitis C will die from the disease (CDC, n.d., National Institutes of Health, n.d.). The prognosis for patients with chronic hepatitis C infection has greatly increased the demand for liver transplants. The acute phase of hepatitis D typically improves within 2 to 3 weeks and liver enzymes return to normal within 16 weeks. Chronic hepatitis develops in about 10% of patients with hepatitis D. Almost all patients with hepatitis E recover completely. Hepatitis E has a 10% to 30% mortality rate in pregnant women. The mortality rate in all others with the disease is about 1% (CDC, n.d., National Institutes of Health, n.d.). Hepatitis G infections frequently coexist with other hepatitis infections, such as hepatitis C. However, most hepatitis G infections are not associated with chronic hepatitis; thus the association of hepatitis G virus with liver disease is, at this time, uncertain.

Recovery from acute toxic hepatitis is rapid if the hepatotoxin is identified early and removed or if exposure to the agent has been limited. However, the prognosis is poor if the period between exposure and the onset of signs and symptoms is prolonged, since there are no effective antidotes.

Liver Abscesses

If an infection develops anywhere along the GI tract, there is a chance of the infecting organisms reaching the liver through the biliary system, portal venous system, or hepatic arterial or lymphatic systems, and creating an abscess (a collection of pus). If an abscess is allowed to progress it can become life-threatening. In the past the mortality rate among patients with liver abscesses was 100% because of the vague clinical symptoms, inadequate diagnostic tools, and inadequate surgical drainage. Today medical management is more successful (University of Maryland Medical Center, 2013).

Etiology and Pathophysiology

If the body is not successful in destroying bacteria, the bacterial toxins attack neighboring liver cells, and the necrotic tissue produced serves as a protective wall for the organism. Meanwhile, leukocytes migrate into the infected area. The result is an abscess: a cavity full of a liquid containing living and dead leukocytes and bacteria. Pyogenic (pus-producing) abscesses of this type may be single or multiple. Common sources of liver abscess include abdominal infections such as appendicitis, diverticulitis, and perforated colon. Other causes include any infection in the blood or bile ducts, and trauma to the liver.

Clinical Manifestations

Patients with liver abscess often present with vague signs and symptoms. Fever accompanied by chills, abdominal pain, and tenderness in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen are common complaints. Unintentional weight loss, jaundice, and weakness are additional symptoms that the patient experiences (University of Maryland Medical Center, 2013).

Assessment

Subjective data are related to the infection and to the inability of the liver to function normally. Symptoms include chills, complaints of dull abdominal pain, abdominal tenderness, and discomfort.

Objective data are also related to the infection and impaired function of the liver. Signs of liver abscess include fever, hepatomegaly, jaundice, and anemia. Clay-colored stools and dark urine are also commonly present because of the decreased amount of bile being excreted.

Diagnostic Tests

The diagnosis is established by demonstrating a space-occupying lesion in the liver radiographically (radiograph, ultrasound, CT, and liver scan). Liver biopsy may be performed to determine the presence of an abscess and a culture may be initiated to determine the infective agent. Common laboratory testing that aids in the diagnosis include bilirubin levels, liver enzymes, blood cultures for bacteria, and a complete blood count (CBC). Amebic liver abscess (caused by a microscopic, single-celled parasite) can also be confirmed by serologic examination (in which ameba-specific antibodies are detected in the patient's serum) (University of Maryland Medical Center, 2013).

Medical Management

Usually liver abscesses are managed by medical therapy. Treatment includes IV antibiotic therapy that is specific to the organism identified. Antibiotic therapy is often continued for 4 to 6 weeks.

Percutaneous (performed through the skin) drainage of a liver abscess is reserved for patients who do not respond to medical therapy or are at high risk for rupture. Open surgical drainage has been the standard in patients whose liver abscesses have ruptured into the peritoneal space, but some of these patients are now being managed with percutaneous drainage. All patients require a full course of antibiotic therapy.

Nursing Interventions and Patient Teaching

Continuous monitoring and supportive care are indicated because of the seriousness of the patient's condition. Monitoring objective and subjective symptoms is important. Notify the health care provider if signs and symptoms increase in severity.

The patient's response to drug therapy is determined by a decrease in fever, tenderness and rigidity of the abdomen, chills, and discomfort. If percutaneous or open surgical drainage is instituted, observe the drainage for amount, color, and consistency.

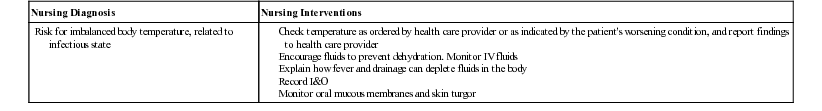

Nursing diagnoses and interventions for the patient with a liver abscess include but are not limited to the following:

| Nursing Diagnosis | Nursing Interventions |

| Risk for imbalanced body temperature, related to infectious state |