Fundamentals of Human Gait

• Describe the primary events of the gait cycle.

• Define the common terms used to describe human gait.

• Describe the muscular and joint interactions that occur during heel contact.

• Describe the muscular and joint interactions that occur during foot flat.

• Describe the muscular and joint interactions that occur during mid stance.

• Describe the muscular and joint interactions that occur during heel off and toe off.

• Describe the muscular and joint interactions that occur during early, mid, and terminal swing.

• Define the common terms that are used to describe human gait.

• Explain the role of the hip abductor muscles during the stance phase of gait.

• Describe common gait deviations, including impairments that may cause the deviations.

Gait refers to the manner in which a person walks. Normally, walking is a very efficient biomechanical process, requiring relatively little use of energy. Although the process appears automatic and easy, walking is actually a complex and high-level motor function.

Normal walking requires a healthy body, especially with regard to the nervous and musculoskeletal systems. Injury and pathology within these systems often result in a significant decrease in the ease and efficiency of walking. Without proper rehabilitation, a person's walking pattern may be unnecessarily labored and inefficient. An individual may also develop compensatory strategies for walking that can cause tightness or prolonged weakness of muscles. The ability to walk safely often determines how soon a person can return home from a hospital or rehabilitation facility. A significant component of a physical therapy evaluation, therefore, is dedicated to analyzing a patient's gait; this is a pre-requisite to determining the best plan of treatment.

Walking represents the ultimate expression of normal kinesiology of the trunk and lower extremities. This chapter studies the primary kinesiologic features of normal gait, with an emphasis on the muscular activation and ranges of motion typically required at the hip, knee, and ankle. This chapter also examines the kinesiology of abnormal gait. Several common gait deviations are described, with the intention of providing a basis from which to effectively treat the underlying pathomechanics.

Terminology

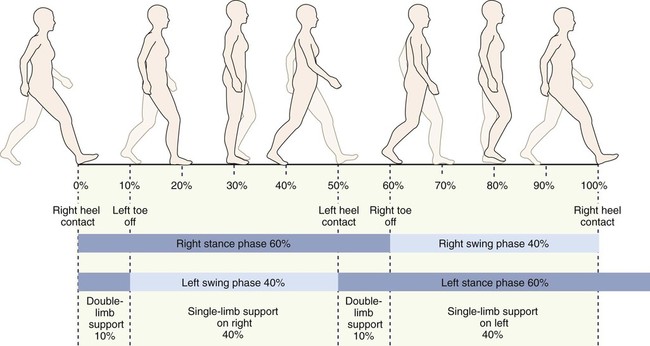

The study of gait uses a special set of terminology. Much of this terminology relates to the events that occur within the gait cycle. The gait cycle describes all the important events that occur between two successive heel contacts of the same limb (Figure 12-1). Because of the dynamic and continuous nature of walking, the gait cycle is described as occurring between 0% and 100% (Figure 12-2). As is shown in Figure 12-2, during the first 60% of the gait cycle, the foot remains in contact with the ground; this is known as the stance phase. The stance phase is subdivided into five events:

• Heel contact: The instant the lower limb contacts the ground (0% of the gait cycle).

• Foot flat: The period that the entire plantar aspect of the foot is on the ground (8% of the gait cycle).

• Mid stance: The point where the body weight passes directly over the supporting lower extremity (30% of the gait cycle); coincides with a vertically oriented lower leg.

• Heel off: The instant the heel leaves the ground (40% of the gait cycle).

• Toe off: The instant the toe leaves the ground (60% of the gait cycle).

A period referred to as push-off is used to describe the combined events of heel off and toe off, when the stance foot is literally “pushing off” toward the next step, typically spanning 40% to 60% of the gait cycle.

In the last 40% of the gait cycle, the limb is off the ground in the swing phase. The swing phase is subdivided into three events (see Figure 12-2):

• Early swing: The period from toe off to mid swing (60% to 75% of the gait cycle).

• Mid swing: The period when the foot of the swing leg passes next to the foot of the stance leg (75% to 85% of the gait cycle). This corresponds to the mid stance phase of the opposite lower extremity.

• Terminal swing: The period ranging from mid swing until heel contact (85% to 100% of the gait cycle).

In addition to the terms that define the events within the gait cycle, the following terms and concepts are useful in the study of gait (Figure 12-3). Note that the following terms are based on a healthy adult, walking at an average speed. Walking faster or slower causes significant changes in these variables.

• Stride: The events that take place between successive heel contacts of the same foot. All events within one stride occur within a gait cycle.

• Step: The events that occur between successive heel contacts of opposite feet, for example, between left and right heel contacts.

• Step length: The distance traveled in one step, which, on average, is about 28 inches in the healthy adult.

• Stride length: The distance traveled in one stride (between two consecutive heel contacts of the same foot); typically 56 inches in the healthy adult.

• Step width: The distance between the heel centers of two consecutive foot contacts. Normally, this distance is about 3 inches in the healthy adult.

• Cadence: The number of steps taken per minute; also called step rate. The average cadence for a healthy adult is 110 steps per minute.

• Walking velocity: The speed at which an individual walks. Normal walking velocity is about 3 miles per hour; walking velocity increases by increases in cadence or step length, or both.

Details of the Gait Cycle

As has been described, the gait cycle is divided into specific events, for example, foot flat, toe off, etc. This section provides the kinesiology unique to these events, with a focus on muscular activation and joint motion.

Although normal gait involves movement in all three planes, the upcoming discussion focuses on the sagittal plane movements of the pelvis, hip, knee, and ankle (talocrural) joints. Figure 12-4 shows the sagittal plane range of motion of the hip, knee, and ankle throughout the full gait cycle. This figure should be referred to throughout the following sections. Bear in mind that the discussions below refer to the kinesiology of a typical adult walking on level surfaces at an average speed.

Stance Phase

The stance phase of gait accounts for approximately the first 60% of the gait cycle. The five events of the gait cycle are listed in the box on the following page.

Heel Contact (0% Point of the Gait Cycle)

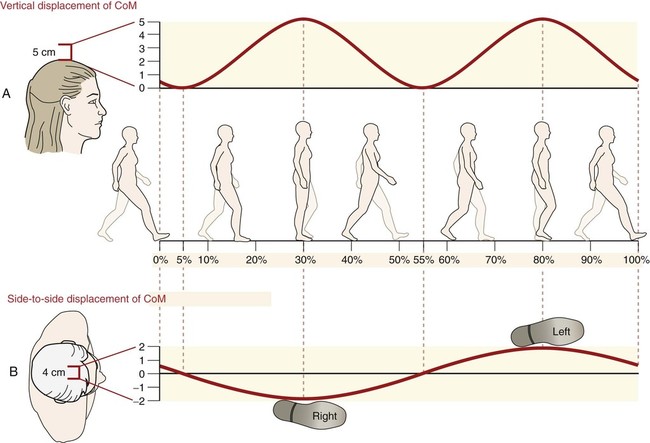

Heel contact marks the beginning of the gait cycle as the heel contacts or strikes the ground (heel contact is often referred to as heel strike) (Figure 12-5, left). At this point in the gait cycle, the center of gravity of the body is at its lowest point. At heel contact, the ankle is held in neutral dorsiflexion through isometric activation of the dorsiflexor muscles. As the ankle transitions toward foot flat (the next event), the dorsiflexor muscles (e.g., tibialis anterior) are eccentrically active to lower the ankle into plantar flexion.

The knee is slightly flexed at heel contact as a way to absorb the shock of initial weight bearing. The quadriceps (knee extensors) are eccentrically active to allow a slight give to the flexed knee and prevent the knee from buckling as weight is transferred onto the stance limb.

The hip is in about 30 degrees of flexion. As weight bearing continues, the hip extensor muscles are isometrically active to prevent the trunk from “jackknifing” forward (see Figure 12-5, left).

Foot Flat (8% Point of the Gait Cycle)

Foot flat is defined as the point at which the entire plantar surface of the foot is in contact with the ground (see Figure 12-5). This event is often described as the loading-response phase. During this time, the muscles and joints of the lower limb assist with shock absorption, as the lower extremity continues to accept increasing amounts of body weight. Immediately after foot flat, the opposite limb begins to leave the ground and enters its early swing phase.

At foot flat, the ankle has just rapidly moved into 5 to 10 degrees of plantar flexion. This motion is controlled through eccentric activation of the dorsiflexor muscles. Immediately after foot flat, the ankle begins to move toward dorsiflexion, as the lower leg advances forward over the foot. Because the calcaneus is fixed under body weight, dorsiflexion of the ankle in the stance phase occurs as the lower leg moves over a fixed foot.

The knee continues to flex to about 15 degrees, acting as a shock-absorbing spring. The knee extensor muscles continue to be active eccentrically, as the hip extensor muscles shift from isometric to slight concentric activation, guiding the hip toward extension (Figure 12-5, right).

Mid Stance (30% Point of the Gait Cycle)

Mid stance occurs as the lower leg approaches the vertical position (Figure 12-6, left). The leg is in single-limb support, as the other limb is freely swinging forward. The hip and the knee are in near extension, as the ankle continues to move into greater dorsiflexion.

At mid stance, the ankle approaches about 5 degrees of dorsiflexion. During this time, the dorsiflexor muscles are inactive; instead, the plantar flexor muscles are eccentrically active, controlling the rate at which the lower leg advances (dorsiflexes) forward over the foot. The knee reaches a near fully extended position. Because the line of gravity falls just anterior to the medial-lateral axis of rotation of the knee, the knee is mechanically locked into extension. Therefore, little activation is normally required of the quadriceps at this time. The hip approaches 0 degrees of extension. The hip extensors such as the gluteus maximus are only slightly active to help stabilize the hip as the body is propelled forward. This activation is minimal during slow walking on level surfaces, but increases significantly with increasing speed and slope of the walking surface.

During mid stance, the stance leg is in single-limb support as the other leg is freely swinging toward the next step. The hip abductor muscles (e.g., gluteus medius) of the stance leg therefore are active to stabilize the hip in the frontal plane, preventing the opposite side of the pelvis from dropping excessively (see Figure 12-6, left).

Heel Off (40% Point of the Gait Cycle)

The events of heel off occur just after mid stance as the lower leg and ankle begin “pushing off” to propel the body upward and forward (Figure 12-6, middle). As the name implies, the heel-off phase begins as the heel breaks contact with the ground.

At the beginning of heel off, the ankle continues to dorsiflex to about 10 degrees. This action stretches the Achilles tendon, which prepares the calf muscles for propulsion. As heel off progresses, the plantar flexor muscles switch their activation from eccentric (to control forward motion of the leg) to concentric. This concentric action produces plantar flexion for propulsion, or push-off.

At heel off, the extended knee prepares to flex, often driven by a short burst of activity from the hamstring muscles. The hip continues to extend to about 10 degrees of extension. Eccentric activation of the hip flexors, in particular the iliopsoas, helps to control the rate and amount of hip extension (see Figure 12-6, middle). Tight ligaments of the hip or tight hip flexor muscles will reduce the amount of hip extension at this point in the gait cycle, thereby reducing stride length.

Toe Off (60% Point of the Gait Cycle)

Toe off is the final event of the stance phase of gait (Figure 12-6, right). The events that occur during this period are designed to complete push-off and begin the early swing phase. As the name implies, toe off coincides with the toes leaving the ground. The contralateral leg begins its foot flat phase and begins to accept a greater portion of body weight.

At toe off, the toes are in marked hyperextension at the metatarsophalangeal joints. The ankle continues plantarflexing (to about 15 degrees) through concentric activation of the plantar flexor muscles. The muscular force for push-off is typically shared between the plantar flexors and the hip extensor muscles. Activation of the gastrocnemius and soleus is usually minimal while walking on level surfaces and at a slow speed but increases significantly with increasing speed and incline.

At toe off, the knee is flexed 30 degrees. In the very end of toe-off phase, the slightly extended hip starts to flex as the result of concentric activation of the hip flexor muscles (see Figure 12-6).

Swing Phase

The swing phase of the gait cycle is subdivided into early swing, mid swing, and terminal swing. Fundamentally, the swing phase advances the leg forward to the next step (Figure 12-8).

Early Swing (60% to 65% of the Gait Cycle)

During early swing, the leg begins to accelerate forward. The plantarflexed ankle begins to dorsiflex through concentric activation of the dorsiflexor muscles. The dorsiflexing ankle allows the foot to clear the ground as it is advanced forward. The knee continues to flex, largely driven by indirect action of the flexing hip. The hip flexor muscles continue to contract, pulling the extended thigh forward (Figure 12-8, left).

Mid Swing (75% to 85% of the Gait Cycle)

At mid swing, the contralateral leg is in mid stance, fully supporting the weight of the body. The ankle is held in neutral dorsiflexion via isometric activation of the dorsiflexor muscles (Figure 12-8, middle).

In mid swing, the knee is flexed about 45 to 55 degrees, which helps shorten the functional length of the lower limb to facilitate its advance. The hip approaches about 30 degrees of flexion through concentric activation of the hip flexor muscles.

Terminal Swing (85% to 100% of the Gait Cycle)

In terminal swing, the limb begins to decelerate in preparation for heel contact (Figure 12-8, right). In the final stages of terminal swing, the leg is placed well in front of the body. The ankle dorsiflexors continue their isometric activation, holding the ankle in neutral dorsiflexion and preparing for heel contact.

The knee has moved from a flexed position in mid swing to almost full extension. Interestingly, the hamstrings are active eccentrically to slow the rapidly extending knee. Individuals who lack the ability to activate their hamstrings just before heel contact are prone to injury because the knee is likely to “snap” forcefully into extension at heel strike.

The hip flexor muscles, which have powered the leg into nearly 35 degrees of flexion, become inactive in terminal swing. The hip extensor muscles are active eccentrically to decelerate the forward progression of the thigh (see Figure 12-8, right).

Summary of the Sagittal Plane Kinesiology of the Gait Cycle

At initial contact, motions at the hip, knee, and ankle (talocrural) joints have functionally elongated the lower extremity. The goal of the action is to maximize stride length. Shortly after heel strike, controlled knee flexion and ankle plantar flexion help to absorb the forces of initial contact. This helps to provide a smooth transition to full weight bearing. The hip and the knee then extend, supporting a critical height of the body's center of mass that allows the contralateral leg to advance and clear the ground. During the first half of the swing phase, all joints of the lower extremity begin to flex, functionally shortening the lower extremity. In terminal swing, the advancing lower extremity is slowed in preparation for the next heel strike.

Summary of the Frontal Plane Kinesiology of the Gait Cycle

The hip abductor muscles stabilize the hip within the frontal plane during the single-limb support phase of walking. When a given limb enters mid stance, the opposite leg is in its swing phase—not in contact with the ground. Activation of the stance leg's hip abductor muscles normally holds the pelvis level, allowing the swing leg to advance toward the next step. Without sufficient strength of the hip abductor muscles on the stance leg, the opposite side of the pelvis may drop excessively under the force of gravity. This abnormal response is known as a positive Trendelenburg sign and strongly suggests weakness of the hip abductor muscles.

The knee is stabilized in the frontal plane primarily by its bony shape and by tension in the medial and lateral collateral ligaments. This natural stability may be lost through ligamentous injury. A torn medial collateral ligament, for example, may lead to genu valgus, potentially altering normal gait mechanics. It is interesting to note that instability of the knee may also arise from impairments at the hip or at the foot. For instance, weakness of the hip abductors or excessive pronation of the foot, or both, may produce excessive valgus strain on the knee during the stance phase. Over time, this strain may over-stretch the medial collateral ligament.

While an individual is walking, the subtalar and transverse tarsal joints dictate much of the frontal plane kinesiology of the foot. These joints help transform the foot from a pliable platform at early stance to a more rigid platform at late stance. The kinematics of the subtalar joint provides an insight into this transformation. After initial heel contact, the subtalar joint everts (pronates) as the medial longitudinal arch of the foot lowers. These events create a more pliable position of the foot—an essential part of the shock-absorbing mechanism of early stance. At mid to late stance, the subtalar joint moves toward inversion (supination), which resets the height of the medial longitudinal arch. The position of inversion arranges the bones of the foot to their most stable position, forming a rigid lever for push-off.

Summary of the Horizontal Plane Kinesiology of the Gait Cycle

While an individual is walking, the horizontal plane movements of the lower extremity are slight and difficult to measure. These motions are, however, very important. The movements are controlled primarily at either end of the lower extremity: Proximally by the hip and distally by the subtalar and transverse tarsal joints. This section will focus primarily on the horizontal plane rotations of the hip that occur during the gait cycle.

During walking, the hip internally and externally rotates in the horizontal plane about a vertical axis of rotation; this occurs as the pelvis rotates about a relatively fixed femur. Consider, for example, rotation of the pelvis (relative to the femur) as observed from a top view (Figure 12-10). During the foot-flat phase on the right leg, the right hip is in external rotation as the left leg enters early swing (Figure 12-10, A). As the gait cycle continues, the pelvis rotates about the right lower extremity (closed-chain internal rotation of the right hip), bringing both hips to a relatively neutral position (Figure 12-10, B). Figure 12-10, C, shows the right leg near the heel-off phase of gait. The right hip has continued to internally rotate, advancing the left side of the pelvis an additional 12 degrees. Fundamentally, from a top view, walking occurs as a series of forward rotations of the “swing side” of the pelvis. Because the trunk remains relatively stationary during walking, the lumbar spine must rotate slightly (in the opposite direction) to decouple the rotating pelvis from the thorax. This subtle but important kinematic function of the lumbar spine is apparent when a person who has a fused or very painful lumbar spine is walking. In this case, the thorax must follow the rotating pelvis nearly degree-for-degree. Ironically, this results in a gait pattern that appears to exaggerate trunk rotation when in fact it results from a lack of rotation at the lumbar spine.

Gait Deviations

Normal walking requires sufficient strength and range of motion of all participating muscles and joints. In addition, adequate sensory feedback (proprioception) and balance are needed to coordinate the movement and posture of the body as a whole. After injury or pathology, walking can become difficult or, at worst, impossible. Fortunately, the human body is remarkably adaptable. Certain biomechanical compensations performed, often subconsciously, by the patient can provide the necessary forces and range of motion for basic gait. Often patients show a very characteristic gait deviation that is associated with a compensation or is a consequence of a given impairment. The following section describes the kinesiology of several common gait deviations.

Atlas

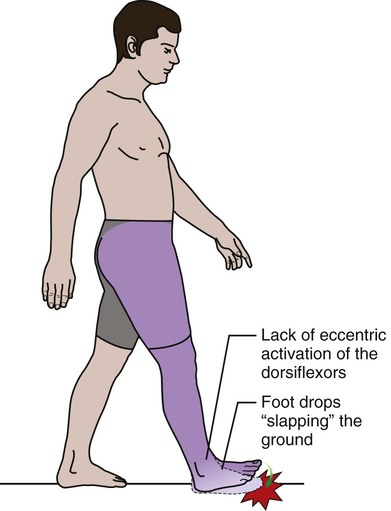

Foot Slap

| Impairment: | Weakness of the dorsiflexors; may follow injury to the deep peroneal nerve (deep fibular nerve), distal neuropathy, or hemiplegia |

| Description of Deviation: | Upon heel strike, the foot quickly drops into plantar flexion, producing a slapping sound as the forefoot hits the ground. |

| Reason for Deviation: | Inability of the dorsiflexor muscles to slowly control plantar flexion |

High Stepping Gait

| Impairment: | Marked weakness of the dorsiflexors, resulting in foot drop |

| Description of Deviation: | Individual appears to be stepping over an imaginary obstacle (hence the term “high stepping”). |

| Reason for Deviation: | To clear the foot from the ground, the hip and knee must be excessively flexed to advance the leg. |

Vaulting Gait

| Impairment: | Any impairment of the lower extremity that reduces the ability to functionally reduce the length of the advancing limb (e.g., inability to flex the hip or the knee) |

| Description of Deviation: | Individual rises up on the toes of the stance foot (left leg in figure) to allow clearance for the contralateral advancing limb. |

| Reason for Deviation: | Standing on tip-toes creates extra clearance for the contralateral (long) leg to clear the ground during swing. |

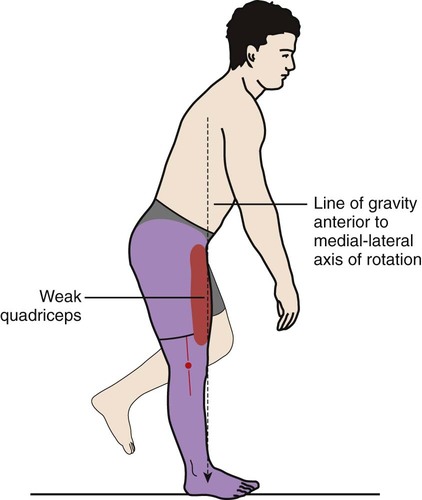

Weak Quadriceps Gait

| Impairment: | Weakness or avoidance of activation of the quadriceps muscle |

| Description of Deviation: | Knee remains fully extended throughout stance; combined with excessive forward lean of the trunk |

| Reason for Deviation: | Forward lean of the trunk shifts the line of gravity anterior to the medial-lateral axis of the knee. This maneuver mechanically locks the knee in extension, reducing the need for activation of the quadriceps muscle. |

| Comments: | This gait deviation may stress the posterior capsule of the knee, potentially leading to genu recurvatum. |

Genu Recurvatum

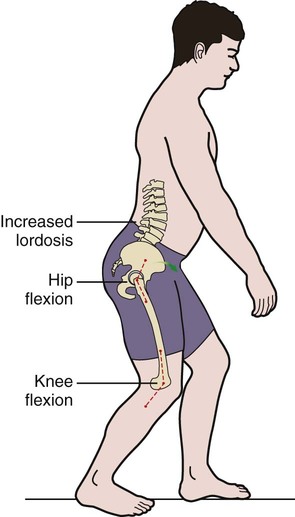

Walking With Hip or Knee Flexion Contracture

| Impairment: | Hip or knee flexion contracture |

| Description of Deviation: | Flexed position of the hip and knee during the stance phase of gait |

| Reason for Deviation: | Increased tightness in tissues that normally allow full hip and knee extension |

| Comments: | Often this deviation is associated with increased lumbar lordosis and reduced stride length. This deviation is often referred to as a “crouched gait” when the walking pattern of a person with cerebral palsy is described. In this case, the hip flexion contracture is often associated with tightness in the hip adductor and internal rotator muscles. |

Weak Gluteus Maximus Gait

| Impairment: | Weakness of the hip extensors, such as gluteus maximus |

| Description of Deviation: | Backward lean of the trunk during early stance phase of gait |

| Reason for Deviation: | Leaning the trunk posteriorly during the stance phase shifts the body's line of gravity posterior to the hip, reducing the demands on the hip extensor muscles. |

Weak Hip Abductor Gait

Hip Hiking Gait

| Impairment: | Inability to functionally shorten the swing leg, for example, weakness of hip flexor muscles |

| Description of Deviation: | Excessive elevation of the pelvis on the side of the swing leg |

| Reason for Deviation: | Elevating, or hiking, the pelvis provides extra clearance for the advancing leg. |

| Comments: | This compensation maneuver often occurs with other maneuvers (for similar reasons) such as circumduction and vaulting. |

Hip Circumduction

| Impairment: | Inability to functionally shorten the swing leg, for example, reduced active or passive hip or knee flexion, or as a consequence of wearing a “straight-leg” brace at the knee |

| Description of Deviation: | Swing leg is advanced in a semicircular arc. |

| Reason for Deviation: | Circumduction creates extra clearance to advance the functionally long leg. |

| Comments: | This maneuver may place additional demands on the hip abductor muscles to help advance the swing limb. |

Summary

Understanding the kinesiology of walking requires a firm understanding of the muscular and joint interactions of the entire lower extremity. This understanding is a vital component of a physical therapy treatment and evaluation. Successful “gait training” usually improves a person's speed, safety, and metabolic efficiency of walking. These variables often dictate an individual's ultimate level of functional independence.