Public health

The principles of public health

The principles of public health

The concept of public health pharmacy

The concept of public health pharmacy

The determinants of health and lifestyle influences on health

The determinants of health and lifestyle influences on health

Introduction

While pharmacists have increasingly received wide recognition for their considerable knowledge, skills and expertise in working with patients to resolve medicines-related issues, they appear to have struggled with the concept of contributing to the wider public health agenda. This is ironic, given that for many years pharmacists have addressed a range of public health issues by giving lifestyle advice, among other services, to the populations they serve on topics such as smoking cessation, diet, substance misuse, sexual health, alcohol and exercise.

However, in recent years, pharmacy has started to recognize its public health contribution, following the publication of key government strategies to develop public health pharmacy. Working with other agencies as part of a multidisciplinary team to address population-wide public health issues is a relatively new challenge that requires additional knowledge and skills, but this has provided new opportunities for pharmacists to become involved in developing and delivering new initiatives to promote healthy living. This chapter will help the reader to understand better the principles of public health and the partnerships required to deliver the public health agenda and identify what the pharmacist can contribute.

What is public health pharmacy?

There are many definitions of public health in common use but perhaps the one most widely used in the UK is:

The science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts and informed choices of society

Central to this definition is the concept that promoting public health is not solely an application of evidence-based science, such as epidemiology. For those working in public health, there is also a need to understand different sociological groupings within society and work with others to support and encourage the population or particular sectors of society to make changes that are likely to bring health benefits. To achieve this, those employed in public health typically work across organizations such as local health service bodies, local authorities and local communities in settings that range from acute hospital trusts and local health organizations to local authorities, social services and the voluntary sector. Much of the work is long term and it may take several years before any outcomes materialize that can have a lasting impact on health. Indeed, this could be viewed as being a ‘health service’, in contrast to the current healthcare system that may more closely resemble an ‘ill health service’. This is because resources are used to encourage people to adopt a healthy lifestyle and protect them from communicable diseases, rather than being primarily targeted at people who are ill.

As a corollary to the definition of public health presented above, public health pharmacy can be defined as:

This definition reflects a pragmatic approach to public health pharmacy and has proved useful to help understand what pharmacy can contribute, but it has mis-led some to believe that public health pharmacy is a discipline in its own right. Rather, public health requires a multidisciplinary team approach and pharmacy is only one of the contributors, often with a strong focus on medicines-related issues.

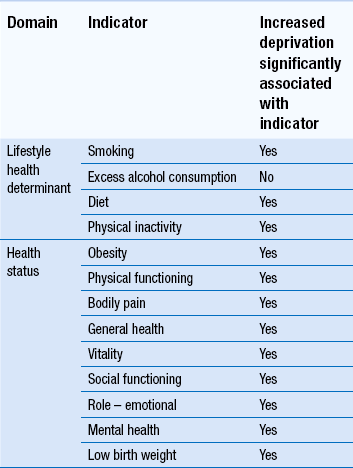

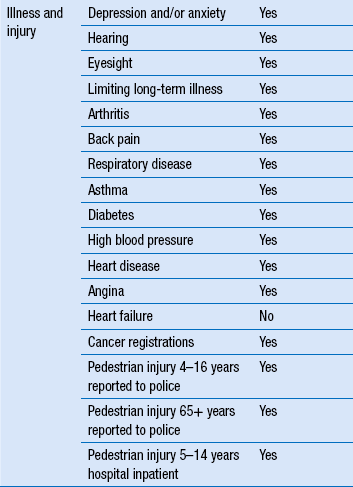

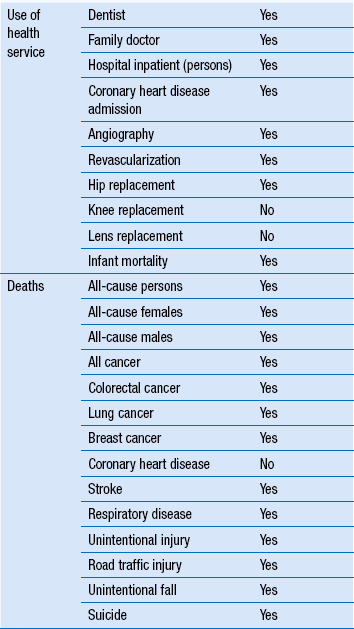

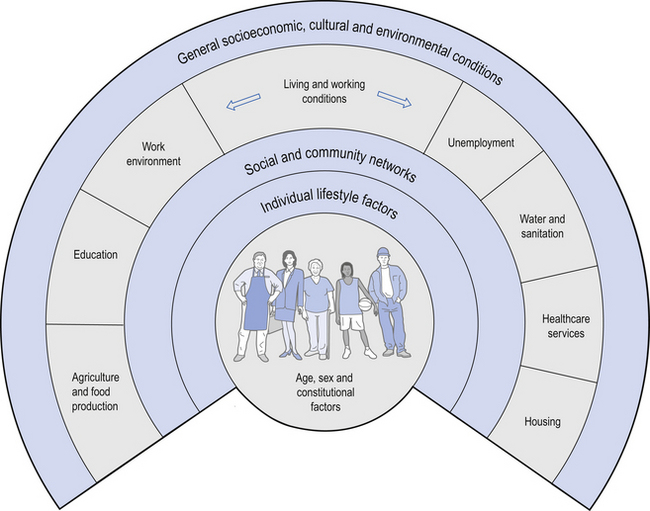

Pharmacy should always be in a position to make an impact on public health, even if it restricts its contribution to medicines-related issues. However, to make an optimal contribution to public health, pharmacy needs to also influence the wider determinants of health. This is more challenging and requires an appreciation that more than 70% of the factors that determine a person’s health lie outside of the domain of health services and instead in their demographic, social, economic and environmental conditions. For example, there is limited opportunity to help a patient with asthma improve their health by advising them on the correct use of their inhaler when wider public health issues also influence treatment outcome. The patient may live in poorly heated, damp, infested accommodation, have a low paid job that involves working in a dusty or dirty environment, be poorly educated, have few or no friends or family to support them and have poor mental health. In addition, they may continue to smoke cigarettes, take little exercise and eat too many foods with a high fat content. It is clear that these factors will impact on good disease management, but the influential factors are often much less obvious than described above. Being aware of the wider determinants of health is important, as each carries a significant health burden, many of which are linked to deprivation. A number of these are summarized in Table 13.1.

Wider determinants of health

Most measures of population health have shown marked improvement over the past 150 years. For example, life expectancy in England and Wales has improved in every decade since the 1840s. In 1841, life expectancy for males was 41 and this had increased to 78.7 years by 2011. The equivalent improvement for females was from 43 to 82.6 years of age. Much of the improvement seen has been the result of environmental and social changes rather than developments in medicine and health care. Despite these overall improvements, social inequalities have widened, with improvements in the health of the most disadvantaged groups being relatively small. To illustrate these inequalities, we can look at the life expectancy of those who live in the most and least deprived areas of our big cities. In Scotland, for example, people living in the most deprived districts of Glasgow have a life expectancy 12 years shorter than those in the most affluent areas. In London, boroughs a few miles apart have markedly different life expectancies. Each of the eight tube stations on the Jubilee line from Westminster to Canning Town represents a decline of one further additional year in life expectancy for the resident population.

The landmark work of Dahlgren and Whitehead in 1991 highlighted the main factors that determine the health of a given population (Fig. 13.1). The age, gender and genetic make-up of an individual clearly influence the health potential of that individual, although each is fixed and non-modifiable. Other factors that influence health and which can be modified to have a favourable impact include addressing individual lifestyle factors such as smoking, diet and physical activity. Improving interactions with friends and relatives, and developing mutual support within a community can help sustain health. Other wider influences on health include living and working conditions, food provision, access to essential goods and services, and the overall socioeconomic, cultural and environmental conditions. There are too many factors to discuss in detail here, but a number of the relevant, key determinants are outlined below. However, the simple message is that, whether attempting to evaluate mortality, morbidity or self-reported health, and regardless of whether it is income, class, house ownership, deprivation, social exclusion or a similar indicator or combination of indicators that is used as the socioeconomic indicator, those who are worse off in society have poorer health.

Employment and unemployment

Both employment and unemployment can be associated with adverse effects on health. Job security has also been recognized as important for well-being. The trend towards less secure, short-term employment affects everyone but is a particular problem for less skilled manual workers. Unemployment imposes a number of health burdens on the unemployed and some of these are summarized in Box 13.1.

In addition to job security, there is considerable evidence that greater control over work is associated with positive health such as lower coronary heart disease, fewer musculoskeletal disorders, reduced mental illness and less sickness absence. The relationship between status in the workforce and health has been demonstrated across the gradient from the top jobs to those at the bottom. The landmark studies with civil servants in Whitehall, London demonstrated that even those in the next grade down from the top had worse health than those in the top posts. Despite being in well paid and relatively secure posts, a health gradient was observed across a range of disorders when compared to those in the top posts.

A confounding issue when trying to interpret the effect of unemployment on health is that people with poorer health are more likely to be unemployed. This is particularly true for people with long-term conditions, although this does not fully explain why the unemployed have poorer health.

Environment air quality

Some of the most enduring images of poor air quality are the photographs taken in the 1950s of London in dense smog. Pollution arising from the burning of domestic coal accounted for a significant number of premature deaths among Londoners. In the London smog of 1952 there was almost a three-fold increase in death in the over 65 s, while deaths from bronchitis and emphysema rose 9.5-fold, pneumonia and influenza increased 4.1-fold and myocardial degeneration increased almost three-fold, along with associated increases in hospital admissions. Although the sulfur dioxide and black smoke from domestic coal is now a thing of the past, other pollutants have taken their place, notably from burning petrol and diesel in cars and other forms of transport. Ambient levels of air pollution continue to be associated with raised morbidity and mortality and are particularly hazardous to the elderly, children and those with pre-existing disease.

Crime

Crime affects not only the health of the victim but also that of the community involved. Fear of crime is a real phenomenon that impacts on both health and well-being. As a consequence of crime or the perception of crime, people make adjustments to their lifestyle and behaviour such as not going out after dark, not going out alone, avoiding certain areas, not using public transport and avoiding young people. Because crime is often concentrated in particular neighbourhoods and the avoidance measures outlined above are adopted, this can weaken social ties and undermine social cohesion in these neighbourhoods.

Energy and housing

It is recognized that energy obtained from fossil fuels must be reduced to meet international commitments on global warming and reduce their associated adverse impact on health. In many UK cities, the trend is for falling use by industry but increased use by transport.

Heating of houses must also become more energy efficient. Typically housing for low income families is the most inefficient with the use of electric fires at standard tariff prices costing three times more than gas central heating. There is a fuel poverty strategy in the UK which seeks to provide heating and insulation improvement for those who spend 10% or more of their income on heating their home. Cold homes exacerbate many existing illnesses such as asthma and make the individual prone to respiratory infections (Box 13.2). In addition, fuel poverty brings opportunity loss. Low income families spend a disproportionate amount of their income in keeping warm and this has an adverse effect on their social well-being, ability to adopt a healthy lifestyle and overall quality of life.

Lifestyle determinants of health

The individual lifestyle determinants of health represent the areas in which pharmacy has traditionally made its most significant contribution to public health (see Ch. 48). These continue to be key ways that pharmacies can promote healthy living. It is therefore important to appreciate that behaviours that can have an adverse impact on health may be associated with one or more of the wider determinants of health, especially social and economic disadvantage. For example, socially and economically disadvantaged people are less likely to eat a good diet and more likely to have a sedentary lifestyle, be obese and abuse alcohol. Cigarette smoking has one of the strongest associations with social disadvantage, with higher levels recorded in more deprived sectors of the population, and this in turn has the greatest cost in terms of premature death.

Smoking

Tobacco smoking remains one of the main avoidable causes of premature death in the UK, estimated as being responsible for more than 81 000 deaths among adults aged 35 and over in 2010 alone. Smoking causes a wide range of serious illnesses including cancer of the lung, respiratory tract, oesophagus, bladder, kidney, stomach and pancreas; respiratory disease, including chronic obstructive lung disease and pneumonia; circulatory disease, such as heart disease, strokes and aneurysms; and digestive disorders, such as ulcers of the stomach and duodenum. Second-hand smoke also puts others at risk and has been linked to lung cancer, strokes, respiratory disorders and infections, particularly in children.

In 2007, before the introduction of the ban on smoking in public in England, Wales and Northern Ireland (smoking in public was banned in 2006 in Scotland), approximately 28% of men and 23% of women were smokers, accounting for up to 10 million people in England alone. In 2011, this was reported to have fallen to 22% of men and 20% of women. Smoking therefore remains a significant problem, despite the decline in prevalence seen over the past 30 years from the 53% of men and 42% of women who smoked in the mid-1970s. Factors that continue to predict the likelihood of smoking include challenging material circumstances, cultural deprivation and stressful marital, personal and household circumstances.

To reduce the health burden of smoking, a number of public health strategies have been put in place and these include reducing the public’s exposure to second-hand smoke, providing more support for smokers to stop, raising public awareness of the health effects of smoking and the benefits of stopping smoking and reducing tobacco advertising and the impact of tobacco promotion, and regulating the sales and design of cigarette packets.

With respect to the no smoking agenda the major contribution of pharmacy is in raising awareness of the harm caused by smoking, supporting strategies to reduce the adverse impact of smoking on health, identifying smokers who want to stop and providing these individuals with behavioural support or referring them to alternative sources of smoking cessation support.

Weight management

The UK is experiencing one of the world’s fastest growing rates of obesity. In 2010, obesity was considered to be at epidemic proportions with over 26% of men and women over 16 years of age and 16% of children classified as being obese. Such classification is often based on determining the body mass index (BMI: defined as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in metres) of an individual. A BMI in the range of 25 kg/m2 to 30 kg/m2 indicates the individual is overweight while a BMI of>30 kg/m2 indicates obesity.

Being overweight can seriously affect an individual’s health and may lead to high blood pressure, type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease, many cancers including colorectal and prostate cancers in men and breast or endometrial cancer in women, osteoarthritis, poor self-image and decreased life expectancy.

Increasingly, the measurement of waist circumference is being undertaken as it presents a simple way of assessing someone’s risk rather than measuring BMI. Men are at an increased health risk if their waist measurement is≥94 cm and at substantially increased health risk if the measurement is≥102 cm. Equivalent waist measurements for women are≥80 cm and≥88 cm.

Raising issues of weight management can be difficult but opportunities for the pharmacist to intervene may arise when a person complains of being unhappy with their weight, short of breath or having mobility problems associated with back or hip pain.

Alcohol

Excessive alcohol intake is associated with a range of health problems including serious liver disease, disorders of the stomach and pancreas, anxiety and depression, sexual problems, high blood pressure and cardiac disease, involvement in accidents, particularly car crashes, a range of cancers, including those of the mouth, throat, liver, colon and breast and becoming overweight or obese.

Alcohol misuse currently accounts for approximately 22 000 deaths each year, with consumption above the recommended limits of 3–4 units/day for men and 2–3 units/day for women being exceeded by 22% of adult females and 39% of adult males. Of equal concern is the fact that 20% of the population in England drink to get drunk (binge drinking). This is defined as consuming more than 8 units for men and more than 6 units for women and is strongly associated with involvement in accidents and with cardiovascular disease.

Most people are sensitive about revealing the details of their drinking habits; however, opportunities for pharmacy staff to raise awareness of sensible drinking may arise when individuals present with a hangover, headache, indigestion or complain of insomnia, excessive tiredness, depression, stress, being overweight or report having been involved in a minor accident. Requests for alternative medicines/complementary therapies that may be used to treat alcohol-related problems or supplying a prescribed or over-the-counter medicine known to interact with alcohol, are further opportunities that may allow discussion with the individual.

Exercise

Regular exercise for adults that is equivalent to at least 30 min/day of moderate physical activity on 5 or more days of the week, can help prevent or manage a range of disorders including cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders, mental illness and a range of cancers. Children are required to undertake at least 60 minutes of moderate activity each day to promote healthy growth, development and psychological well-being. Recent surveys have shown less than 37% of adult men and 24% of women undertake sufficient exercise to gain any health benefit. Older people need to maintain their mobility and undertake regular daily activity, and attempts to improve strength, coordination and balance may be particularly beneficial.

Clearly the amount of physical activity an individual needs to undertake will be influenced by their daily routine and nature of their job. Opportunities for pharmacy staff to raise issues relating to physical activity may arise when people are unhappy with their weight, complain of being short of breath or tired, have mobility problems, suffer from depression or stress or have difficulty sleeping. Similarly, the purchase of support equipment, e.g. for knees, requesting alternative or complementary medicines to provide energy or obtaining prescribed or purchased medicines for blood pressure may be additional opportunities.

Changing habits and lifestyle

To assist people in making changes to their habits and lifestyle, there is a need to recognize the part played by sociocultural influences and the environment. There are many models that are used to help understand the change process. One that has found use within public health is the ‘three Es model for lifestyle change’. In this model three stages are identified:

Encouragement involves raising awareness and may include the use of adverts, leaflets, one-to-one advice and targeted campaigns, among other approaches. This stage of the change process is used to act as a trigger for people to make healthy choices or at least consider the healthy options. However, by itself, encouragement is unlikely to bring about sustained change in the population without empowerment and changes to environmental factors.

Empowerment involves the education and development of the individual and the community. Central to empowerment is the development of knowledge, life skills and confidence that will enable individuals, groups or populations to make the healthy choice. This process can be enhanced by pharmacy staff who can instill confidence in patients rather than undermining them, and by making changes to environmental factors.

Environment changes are targeted at the social, cultural, economic and physical surroundings in which people live and work. These changes aim to make the healthy choice the easy option. Initiatives aiming to make environmental changes tend to be most effective if instituted on a national basis (e.g. bans on smoking in public places).

A good example that can be used to illustrate the three Es approach to the process of lifestyle change is the need for the wider population to reduce their intake of salt to<6 g/day. ‘Encouragement’ could involve a campaign to raise awareness of the daily intake of salt and the harmful effect of excessive intake; ‘empowerment’ might target the labels on food and ensure they are easy for everyone to understand and to know what they are consuming; changes to the ‘environment’ could involve a reduction in the salt content of prepared foods by manufacturers and the availability of low salt options in supermarkets and restaurants, thereby making it easier for consumers to reduce dietary salt intake. It is important for pharmacists to recognize that there are numerous ways that public health pharmacy can contribute to this process at both local and national levels.

Conclusion

This chapter has highlighted the key determinants of health and focused on areas of lifestyle advice where pharmacy has traditionally contributed to the public health agenda. Hopefully it is apparent to the reader that to make a substantive contribution to public health, pharmacy will need to build on its traditional roles. Some public health pharmacy roles, such as assessing the health and social needs of communities through involvement in surveillance, surveys and information gathering exercises, acting as an advocate for local communities on health issues, and building sustainable communities or working in partnership with relevant statutory and voluntary services to promote and protect the health of the public, may be seen as roles best undertaken by individuals who choose to specialize in public health. Nevertheless, a large number of public health activities can be undertaken from any pharmacy, whether it is located in the community or hospital sector. Some of these are identified in Box 13.3.

Key Points

Pharmacists have many opportunities to promote health

Pharmacists have many opportunities to promote health

Public health pharmacy can be defined in many ways

Public health pharmacy can be defined in many ways

More than 70% of the factors affecting an individual’s health are outside the domain of the health services

More than 70% of the factors affecting an individual’s health are outside the domain of the health services

Public health has improved markedly during the past 150 years

Public health has improved markedly during the past 150 years

During this time, social inequalities have widened, with disadvantaged groups showing little improvement

During this time, social inequalities have widened, with disadvantaged groups showing little improvement

A wide range of factors affect the health of an individual, some of which are fixed, while others can be modified

A wide range of factors affect the health of an individual, some of which are fixed, while others can be modified

Both employment and unemployment are associated with adverse health effects

Both employment and unemployment are associated with adverse health effects

Air pollution is associated with raised morbidity and mortality

Air pollution is associated with raised morbidity and mortality

It is with individual lifestyle determinants that pharmacists have had a traditional role

It is with individual lifestyle determinants that pharmacists have had a traditional role

Community pharmacists may offer support with smoking cessation, weight management, exercise and problems with alcohol

Community pharmacists may offer support with smoking cessation, weight management, exercise and problems with alcohol

To help people change lifestyle or habit, think – encouragement, empowerment, environment

To help people change lifestyle or habit, think – encouragement, empowerment, environment