Thorax

1 Introduction

The thorax lies between the neck and abdomen, encasing the great vessels, heart, and lungs, and provides a conduit for structures passing between the head and neck superiorly and the abdomen, pelvis, and lower limbs inferiorly. Functionally, the thorax and its encased visceral structures are involved in the following:

• Protection: the thoracic cage and its muscles protect the vital structures in the thorax.

• Support: the thoracic cage provides muscular support for the upper limb.

• Conduit: the thorax provides for a superior and an inferior thoracic aperture and a central mediastinum.

• Segmentation: the thorax provides an excellent example of segmentation, a hallmark of the vertebrate body plan.

• Breathing: movements of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles are essential for expanding the thoracic cavity to facilitate the entry of air into the lungs in the process of breathing.

• Pumping blood: the thorax contains the heart, which pumps blood through the pulmonary and systemic circulations.

The sternum, ribs (12 pairs), and thoracic vertebrae (12) encircle the thoracic contents and provide a stable thoracic cage that both protects the visceral structures of the thorax and offers assistance with breathing. Because of the lower extent of the rib cage, the thorax also offers protection for some of the abdominal viscera, including the liver and gallbladder on the right side, the stomach and spleen on the left side, and the adrenal (suprarenal) glands and upper poles of the kidneys on both sides.

The superior thoracic aperture (the anatomical thoracic inlet) conveys large vessels, important nerves, the thoracic lymphatic duct, the trachea, and the esophagus between the neck and thorax. Clinicians often refer to “thoracic outlet syndrome,” which describes symptoms associated with compression of the brachial plexus as it passes over the first rib (specifically, the T1 ventral ramus). Technically, this is a misnomer because these nerves are not exiting the superior thoracic aperture (thoracic inlet). The inferior thoracic aperture (the anatomical thoracic outlet) conveys the inferior vena cava (IVC), aorta, esophagus, nerves, and thoracic lymphatic duct between the thorax and the abdominal cavity. Additionally, the thorax contains two pleural cavities laterally and a central “middle space” called the mediastinum, which is divided as follows (Fig. 3-1):

• Superior mediastinum: a midline compartment that lies above an imaginary horizontal plane that passes through the manubrium of the sternum (sternal angle of Louis) and the intervertebral disc between the T4 and T5 vertebrae

• Inferior mediastinum: the midline compartment below this same horizontal plane, which is further subdivided into an anterior, middle (contains the heart), and posterior mediastinum

2 Surface Anatomy

Key Landmarks

Key surface landmarks for thoracic structures include the following (Fig. 3-2):

• Jugular (suprasternal) notch: a notch marking the level of the second thoracic vertebra, the top of the manubrium, and the midpoint between the articulation of the two clavicles. The trachea is palpable in the suprasternal notch.

• Sternal angle (of Louis): marks the articulation between the manubrium and body of the sternum, the dividing line between the superior and the inferior mediastinum, and the site of articulation of the second ribs (useful for counting ribs and intercostal spaces).

• Nipple: marks the T4 dermatome and approximate level of the dome of the diaphragm on the right side.

• Xiphoid process: marks the inferior extent of the sternum and the anterior attachment point of the diaphragm.

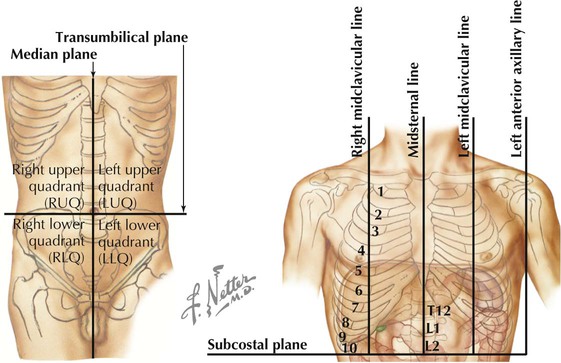

Planes of Reference

In addition to the sternal angle of Louis, physicians often use other imaginary planes of reference to assist in locating underlying visceral structures of clinical importance. Important vertical planes of reference include the following (Fig. 3-3):

• Anterior axillary line: inferolateral margin of the pectoralis major muscle; demarcates the anterior axillary fold.

• Posterior axillary line: margin of the latissimus dorsi and teres major muscles; demarcates the posterior axillary fold.

• Scapular line: intersects the inferior angles of the scapula.

• Midvertebral line: also called the “posterior median” line.

3 Thoracic Wall

Thoracic Cage

The thoracic cage, which is part of the axial skeleton, includes the thoracic vertebrae, the midline sternum, the 12 pairs of ribs (each with a head, neck, tubercle, and body; floating ribs 11 and 12 are short and do not have a neck or tubercle), and the costal cartilages (Fig. 3-4). This bony framework provides the scaffolding for attachment of the chest wall muscles and the pectoral girdle, which includes the clavicle and scapula and forms the attachment of the upper limb to the thoracic cage at the shoulder joint (Table 3-1).

TABLE 3-1

| STRUCTURE | CHARACTERISTICS |

| Sternum | Long, flat bone composed of the manubrium, body, and xiphoid process |

| True ribs | Ribs 1-7: articulate with the sternum directly |

| False ribs | Ribs 8-12: articulate to costal cartilages of the ribs above |

| Floating ribs | Ribs 11 and 12: articulate with vertebrae only |

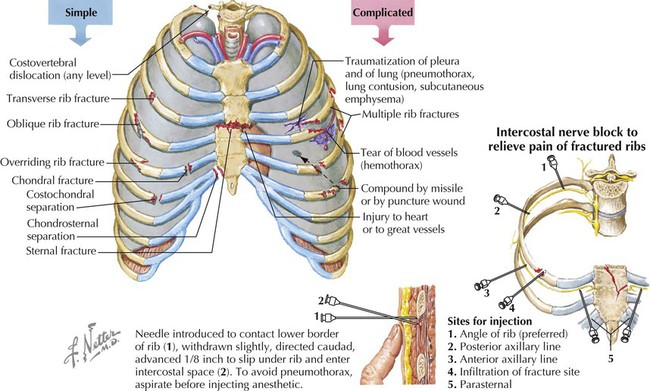

Rib fractures can be a painful injury (we must continue to breathe) but are less common in children because their thoracic wall is still fairly elastic. The weakest part of the rib is the angle.

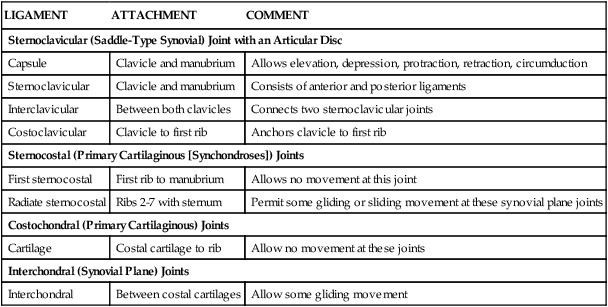

Joints of Thoracic Cage

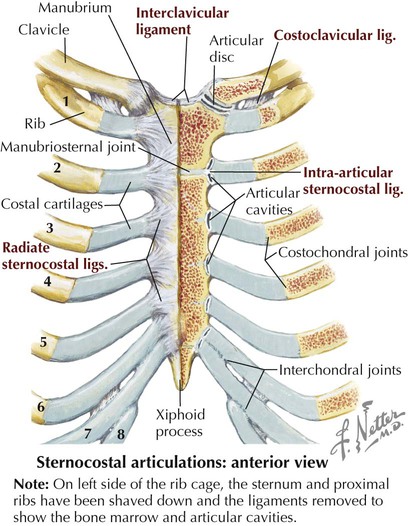

Joints of the thoracic cage include articulations between the ribs and the sternum and thoracic vertebrae and between the sternum and the clavicle and are summarized in Figure 3-5 and Table 3-2.

TABLE 3-2

| LIGAMENT | ATTACHMENT | COMMENT |

| Sternoclavicular (Saddle-Type Synovial) Joint with an Articular Disc | ||

| Capsule | Clavicle and manubrium | Allows elevation, depression, protraction, retraction, circumduction |

| Sternoclavicular | Clavicle and manubrium | Consists of anterior and posterior ligaments |

| Interclavicular | Between both clavicles | Connects two sternoclavicular joints |

| Costoclavicular | Clavicle to first rib | Anchors clavicle to first rib |

| Sternocostal (Primary Cartilaginous [Synchondroses]) Joints | ||

| First sternocostal | First rib to manubrium | Allows no movement at this joint |

| Radiate sternocostal | Ribs 2-7 with sternum | Permit some gliding or sliding movement at these synovial plane joints |

| Costochondral (Primary Cartilaginous) Joints | ||

| Cartilage | Costal cartilage to rib | Allow no movement at these joints |

| Interchondral (Synovial Plane) Joints | ||

| Interchondral | Between costal cartilages | Allow some gliding movement |

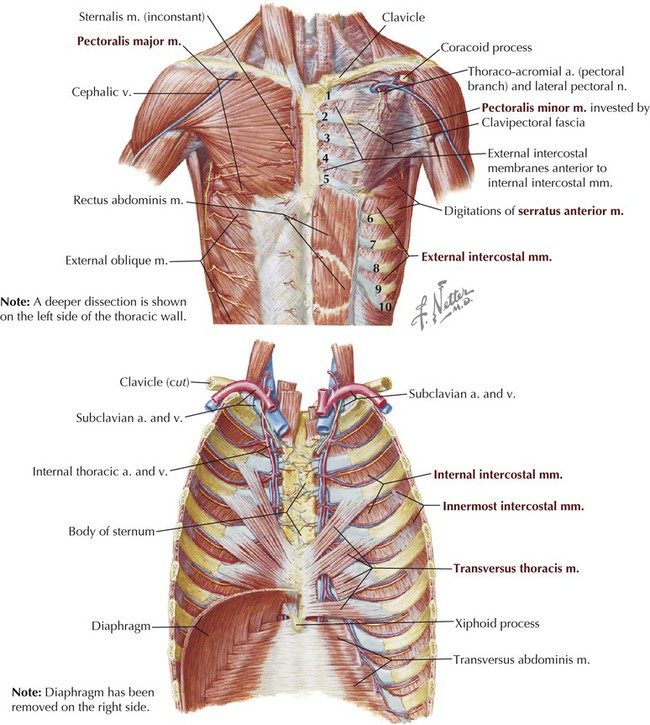

Muscles of Anterior Thoracic Wall

The musculature of the anterior thoracic wall include several muscles that attach to the thoracic cage but that actually are muscles that act on the upper limb (Fig. 3-6). These muscles are as follows (for a review, see Chapter 7):

The true anterior thoracic wall muscles fill the intercostal spaces or support the ribs, act on the ribs (elevate or depress the ribs), and keep the intercostal spaces rigid, thereby preventing them from bulging out during expiration and being drawn in during inspiration (Fig. 3-6 and Table 3-3). Note that the external intercostal muscles are replaced by the anterior intercostal membrane at the costochondral junction anteriorly, and that the internal intercostal muscles extend posteriorly to the angle and then are replaced by the posterior intercostal membrane. The innermost intercostal muscles lie deep to the internal intercostals and extend from the midclavicular line to about the angles of the ribs posteriorly.

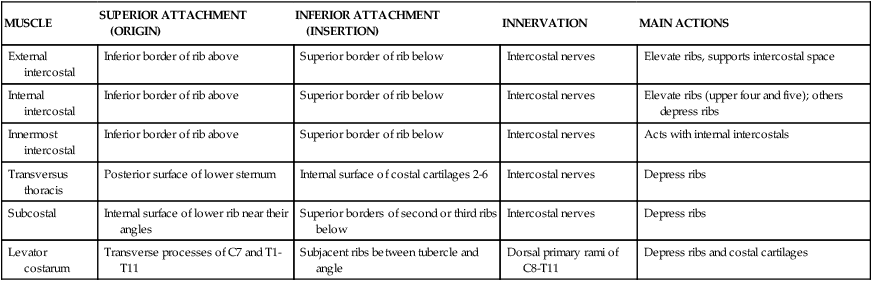

TABLE 3-3

Muscles of the Anterior Thoracic Wall

| MUSCLE | SUPERIOR ATTACHMENT (ORIGIN) | INFERIOR ATTACHMENT (INSERTION) | INNERVATION | MAIN ACTIONS |

| External intercostal | Inferior border of rib above | Superior border of rib below | Intercostal nerves | Elevate ribs, supports intercostal space |

| Internal intercostal | Inferior border of rib above | Superior border of rib below | Intercostal nerves | Elevate ribs (upper four and five); others depress ribs |

| Innermost intercostal | Inferior border of rib above | Superior border of rib below | Intercostal nerves | Acts with internal intercostals |

| Transversus thoracis | Posterior surface of lower sternum | Internal surface of costal cartilages 2-6 | Intercostal nerves | Depress ribs |

| Subcostal | Internal surface of lower rib near their angles | Superior borders of second or third ribs below | Intercostal nerves | Depress ribs |

| Levator costarum | Transverse processes of C7 and T1-T11 | Subjacent ribs between tubercle and angle | Dorsal primary rami of C8-T11 | Depress ribs and costal cartilages |

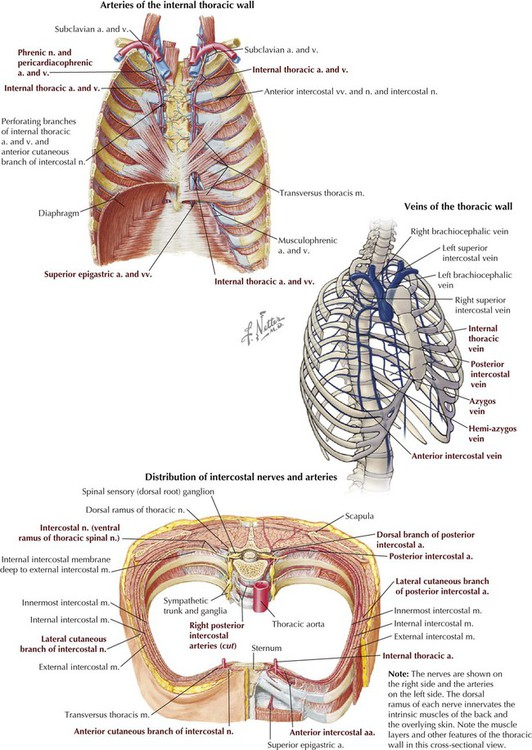

Intercostal Vessels and Nerves

The intercostal neurovascular bundles (vein, artery, and nerve) lie inferior to each rib, running in the costal groove deep to the internal intercostal muscles (Fig. 3-7 and Table 3-4). The veins largely correspond to the arteries and drain into the azygos system of veins or the internal thoracic veins. The intercostal arteries form an anastomotic loop between the internal thoracic artery (branches of anterior intercostal arteries arise here) and the thoracic aorta posteriorly. Posterior intercostal arteries arise from the aorta, except for the first two, which arise from the supreme intercostal artery, a branch of the costocervical trunk of the subclavian artery.

TABLE 3-4

Arteries of the Internal Thoracic Wall

| ARTERY | COURSE |

| Internal thoracic | Arises from subclavian and terminates by dividing into superior epigastric and musculophrenic arteries. |

| Intercostals | First two posterior branches derived from superior intercostal branch of costocervical trunk and lower nine from thoracic aorta; these anastomose with anterior branches derived from internal thoracic artery (1st-6th spaces) or its musculophrenic branch (7th-9th spaces); the lowest two spaces only have posterior branches. |

| Subcostal | From aorta, courses inferior to the 12th rib. |

| Pericardiacophrenic | From internal thoracic and accompanies phrenic nerve. |

The intercostal nerves are the ventral rami of the first 11 thoracic spinal nerves. The 12th thoracic nerve gives rise to the subcostal nerve, which courses inferior to the 12th rib. The nerves give rise to lateral and anterior cutaneous branches and branches innervating the intercostal muscles (Fig. 3-7).

Female Breast

The female breast extends from approximately the second to the sixth ribs and from the sternum medially to the midaxillary line laterally. Mammary tissue is composed of compound tubuloacinar glands organized into about 15 to 20 lobes, which are supported and separated from each other by fibrous connective tissue septae (the suspensory ligaments of Cooper) and fat. Each lobe is divided in lobules of secretory acini and their ducts. Features of the breast include the following (Fig. 3-8):

• Breast: fatty tissue containing glands that produce milk; lies in the superficial fascia above the retromammary space, which lies above the deep pectoral fascia enveloping the pectoralis major muscle.

• Areola: circular pigmented skin surrounding the nipple; it contains modified sebaceous and sweat glands (glands of Montgomery) that lubricate the nipple and keep it supple.

• Nipple: site of opening for the lactiferous ducts; usually lies at about the level of the fourth intercostal space.

• Axillary tail (of Spence): extension of mammary tissue superolaterally toward the axilla.

• Lymphatic system: lymph is drained from breast tissues; about 75% of lymphatic drainage is to the axillary lymph nodes (Fig. 3-9; see also Fig. 7-11), and the remainder drains to infraclavicular, pectoral, or parasternal nodes.

The primary arterial supply to the breast includes the following:

• Anterior intercostal branches of the internal thoracic (mammary) arteries (from the subclavian artery)

• Lateral mammary branches of the lateral thoracic artery (a branch of the axillary artery)

The venous drainage (Fig. 3-9) largely parallels the arterial supply, finally draining into the internal thoracic, axillary, and adjacent intercostal veins.

4 Pleura and Lungs

Pleural Spaces (Cavities)

The thorax is divided into the following three compartments:

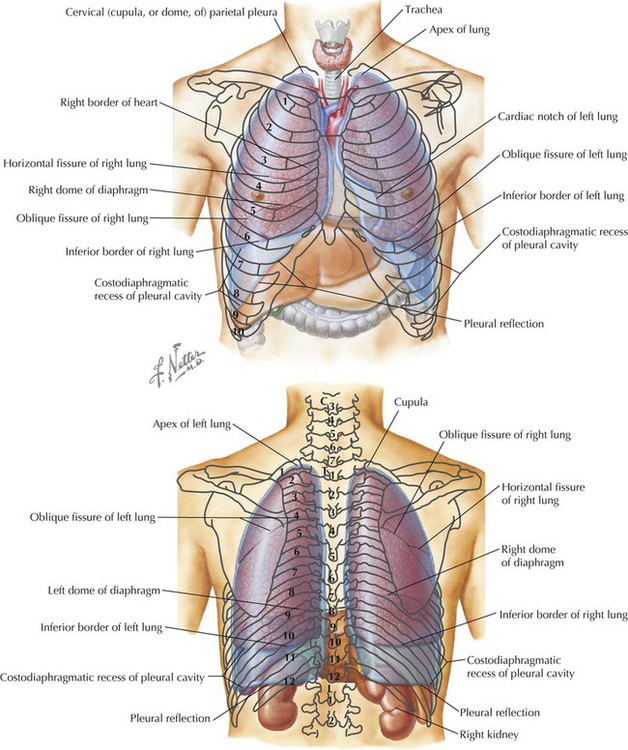

The lungs lie within the pleural cavity (right and left) (Fig. 3-10). This “potential space” is between the investing visceral pleura, which closely envelops each lung, and the parietal pleura, which reflects off each lung and lines the inner aspect of the thoracic wall, the superior surface of the diaphragm, and the sides of the pericardial sac (Table 3-5). Normally, the pleural cavity contains a small amount of serous fluid, which lubricates the surfaces and reduces friction during respiration. The parietal pleura is richly innervated with afferent fibers that course in the somatic intercostal nerves and, over the surface of the diaphragm, the phrenic nerve (C3-C5); the visceral pleura has few, if any, pain fibers.

TABLE 3-5

| STRUCTURE | DEFINITION |

| Cupula | Dome of cervical parietal pleura extending above the first rib |

| Parietal pleura | Membrane that in descriptive terms includes costal, mediastinal, diaphragmatic, and cervical (cupula) pleura |

| Pleural reflections | Points at which parietal pleurae reflect off one surface and extend onto another (e.g., costal to diaphragmatic) |

| Pleural recesses | Reflection points at which lung does not fully extend into the pleural space (e.g., costodiaphragmatic, costomediastinal) |

Clinically, it is important for physicians to be able to “visualize” the extent of the lungs and pleural cavities topographically on the surface of their patients (Fig. 3-10). The lungs lie adjacent to the parietal pleura inferiorly to the sixth costal cartilage. (Note the presence of the cardiac notch on the left side.) Beyond this point, the lungs do not occupy the full extent of the pleural cavity during quiet respiration. These points are important to know if one needs access to the pleural cavity without injuring the lungs (Table 3-6), such as to drain inflammatory exudate (pleural effusion), hemorrhage into the cavity (hemothorax), or air (pneumothorax). In quiet respiration, the lung margins reside two ribs above the extent of the pleural cavity at the midclavicular, midaxillary, and midscapular lines.

TABLE 3-6

Surface Landmarks of the Pleura and Lungs

| LANDMARK | MARGIN OF LUNG | MARGIN OF PLEURA |

| Midclavicular line | 6th rib | 8th rib |

| Midaxillary line | 8th rib | 10th rib |

| Midscapular line | 10th rib | 12th rib |

The Lungs

The paired lungs are invested in the visceral pleura and are attached to mediastinal structures (trachea and heart) at their hilum. Each lung possesses the following surfaces:

• Apex: superior part of the upper lobe that extends into the root of the neck (above the clavicles).

• Hilum: area located on the medial aspect through which structures enter and leave the lung.

• Costal: anterior, lateral, and posterior aspects of the lung in contact with the costal elements of the internal thoracic cage.

• Diaphragmatic: inferior part of the lung in contact with the underlying diaphragm.

The right lung has three lobes and is slightly larger than the left lung, which has two lobes. Both lungs are composed of spongy and elastic tissue, which readily expands and contracts to conform to the internal contours of the thoracic cage (Fig. 3-11 and Table 3-7).

TABLE 3-7

External Features of the Lungs

| STRUCTURE | CHARACTERISTICS |

| Lobes | Three lobes (superior, middle, inferior) in right lung; two in left lung |

| Horizontal fissure | Only on right lung, extends along line of fourth rib |

| Oblique fissure | On both lungs, extends from T2 vertebra to sixth costal cartilage |

| Impressions | Made by adjacent structures, in fixed lungs |

| Hilum | Points at which structures (bronchus, vessels, nerves, lymphatics) enter or leave lungs |

| Lingula | Tongue-shaped feature of left lung |

| Cardiac notch | Indentation for the heart, in left lung |

| Pulmonary ligament | Double layer of parietal pleura hanging from the hilum that marks reflection of visceral pleura to parietal pleura |

| Bronchopulmonary segment | 10 functional segments in each lung supplied by a segmental bronchus and a segmental artery from the pulmonary artery |

The lung's parenchyma is supplied by several small bronchial arteries that arise from the proximal portion of the descending thoracic aorta. Usually, one small right bronchial artery and a pair of left bronchial arteries (superior and inferior) can be found on the posterior aspect of the main bronchi. Although much of this blood returns to the heart via the pulmonary veins, some also collects into small bronchial veins that drain into the azygos system of veins (see Fig. 3-25).

The lymphatic drainage of both lungs is to pulmonary (intrapulmonary) and bronchopulmonary (hilar) nodes (i.e., from distal sites to the proximal hilum). Lymph then drains into tracheobronchial nodes at the tracheal bifurcation and into right and left paratracheal nodes (Fig. 3-12).

As visceral structures, the lungs are innervated by the autonomic nervous system. Sympathetic bronchodilator fibers, which relax smooth muscle, arise from upper thoracic spinal cord segments. Parasympathetic bronchoconstrictor fibers, which contract smooth muscle and increase mucus secretion, arise from the vagus nerve.

Respiration

During quiet inspiration the contraction of the diaphragm alone accounts for most of the decrease in intrapleural pressure, allowing air to expand the lungs. Active inspiration occurs when the diaphragm and intercostal muscles together increase the diameter of the thoracic wall, decreasing intrapleural pressure even more. Although the first rib is stationary, ribs 2 to 6 tend to increase the anteroposterior diameter of the chest wall, and the lower ribs mainly increase the transverse diameter. Accessory muscles of inspiration that attach to the thoracic cage may also assist in very deep inspiration.

During quiet expiration the elastic recoil of the lungs and thoracic cage expel the air. In forced expiration the abdominal muscles contract and, by compressing the abdominal viscera superiorly, raise the intraabdominal pressure and force the diaphragm upward. Having the “wind knocked out of you” shows how forceful this maneuver can be.

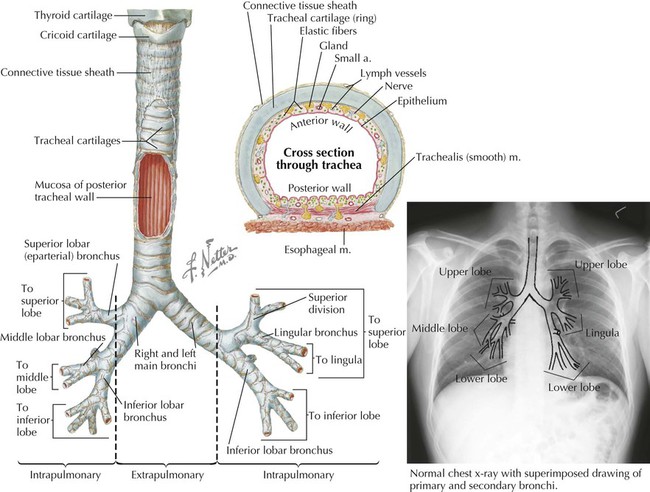

Trachea and Bronchi

The trachea is a single midline airway that extends from the cricoid cartilage to its bifurcation at the sternal angle of Louis. It lies anterior to the esophagus and is rigidly supported by 16 to 20 C-shaped cartilaginous rings (Fig. 3-13 and Table 3-8). The trachea may be displaced if adjacent structures become enlarged (usually the thyroid gland or aortic arch).

TABLE 3-8

Features of the Trachea and Bronchi

| STRUCTURE | CHARACTERISTICS |

| Trachea | Approximately 5 inches (10 cm) long and 1 inch in diameter; courses inferiorly anterior to esophagus and posterior to aortic arch |

| Cartilaginous rings | Are 16-20 C-shaped rings |

| Bronchus | Divides into right and left main (primary) bronchi at level of sternal angle of Louis |

| Right bronchus | Shorter, wider, and more vertical than left bronchus; aspirated foreign objects more likely to pass into right bronchus |

| Carina | Internal, keel-like cartilage at bifurcation of trachea |

| Secondary bronchi | Supply lobes of each lung (three on right, two on left) |

| Tertiary bronchi | Supply bronchopulmonary segments (10 for each lung) |

The trachea bifurcates inferiorly into a right main bronchus and a left main bronchus, which enter the hilum of the right lung and the left lung, respectively, and immediately divide into lobar (secondary) bronchi (Fig. 3-13). The right main bronchus often gives rise to the superior lobar (eparterial) bronchus just before entering the hilum of the right lung. Each lobar bronchus then divides again into tertiary bronchi supplying the 10 bronchopulmonary segments of each lung (sometimes the left lung may have 8 to 10 segments) (Fig. 3-13 and Tables 3-7 and 3-8). The bronchopulmonary segments are lung segments that are supplied by a tertiary bronchus and a segmental artery of the pulmonary artery that passes to each lung. The bronchi and respiratory airways continue to divide into smaller and smaller passageways until they terminate in alveolar sacs (about 23 divisional generations from the right and left main bronchi). Gas exchange occurs only in these most distal respiratory regions.

The right main bronchus is shorter, more vertical, and wider than the left main bronchus. Therefore, aspirated objects often pass more easily into the right main bronchus and right lung.

5 Pericardium and Heart

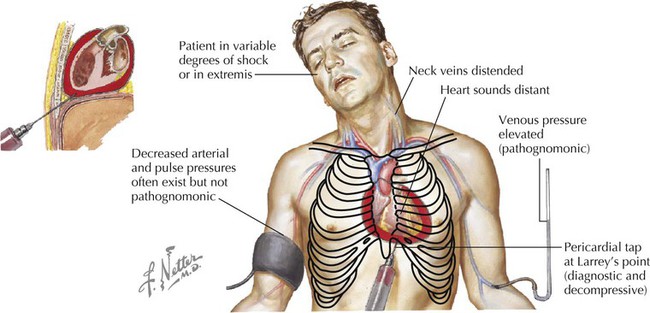

The Pericardium

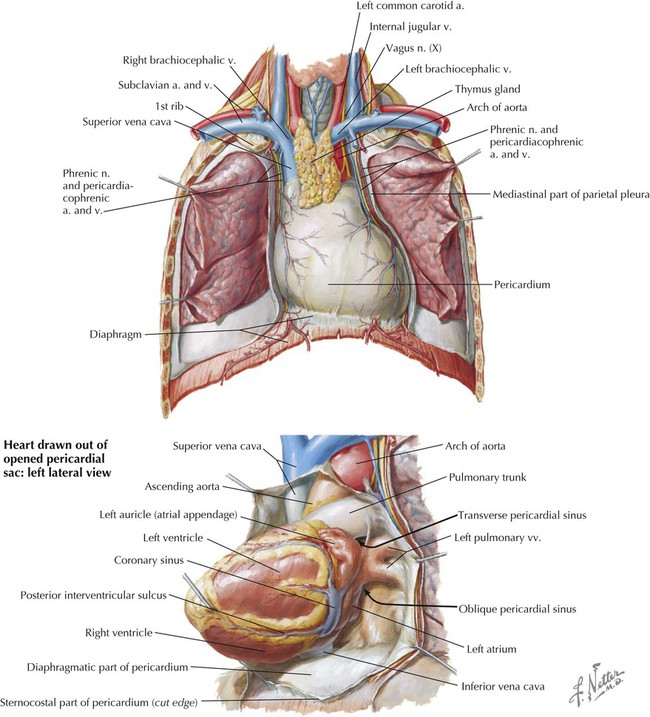

The pericardium and heart lie within the middle mediastinum. The heart is enclosed within a fibroserous pericardial pouch that extends and blends into the adventitia of the great vessels that enter or leave the heart. The pericardium has a fibrous outer layer that is lined internally by a serous layer, the parietal serous layer, which then reflects onto the heart and becomes the visceral serous layer, which is the outer covering of the heart itself, also known as the epicardium (Fig. 3-14 and Table 3-9). These two serous layers form a potential space known as the pericardial sac (cavity).

TABLE 3-9

| STRUCTURE | DEFINITION |

| Fibrous pericardium | Tough, outer layer that reflects onto great vessels |

| Serous pericardium | Layer that lines inner aspect of fibrous pericardium (parietal layer); reflects onto heart as epicardium (visceral layer) |

| Innervation | Phrenic nerve (C3-C5) for conveying pain; vasomotor innervation via sympathetics |

| Transverse sinus | Space posterior to aorta and pulmonary trunk; can clamp vessels with fingers in this sinus and above |

| Oblique sinus | Pericardial space posterior to heart |

The Heart

The heart is essentially two muscular pumps in series. The two atria contract in unison, followed by contraction of the two ventricles. The right side of the heart receives the blood from the systemic circulation and pumps it into the pulmonary circulation of the lungs. The left side of the heart receives the blood from the pulmonary circulation and pumps it into the systemic circulation, thus perfusing the organs and tissues of the entire body, including the heart itself. In situ, the heart is oriented in the middle mediastinum and has the following descriptive relationships (Fig. 3-15):

• Anterior (sternocostal): the right atrium, right ventricle, and part of the left ventricle

• Posterior (base): the left atrium

• Inferior (diaphragmatic): some of the right ventricle and most of the left ventricle

• Acute angle: the sharp right ventricular margin of the heart

• Obtuse angle: the more rounded left margin of the heart

• Apex: the inferolateral part of the left ventricle at the fourth to fifth intercostal space

The atrioventricular groove (coronary sulcus) separates the two atria from the ventricles and marks the locations of the right coronary artery and the circumflex branch of the left coronary artery. The anterior and posterior interventricular grooves mark the locations of the left anterior descending (anterior interventricular) branch of the left coronary artery and the posterior descending (posterior interventricular) artery, respectively.

Coronary Arteries and Cardiac Veins

The right and left coronary arteries arise immediately superior to the right and left cusps, respectively, of the aortic semilunar valve (Fig. 3-16). The right coronary artery passes between the pulmonary trunk and right atrium in the right atrioventricular groove and passes around the acute angle of the heart. The left coronary artery passes behind the pulmonary trunk, reaches the left atrioventricular groove and divides into the anterior interventricular and circumflex branches. During ventricular diastole, blood enters the coronary arteries to supply the myocardium of each chamber. About 5% of the cardiac output goes to the heart itself.

The corresponding great cardiac vein, middle cardiac vein, and small cardiac vein parallel the left anterior descending (LAD) branch of the left coronary artery, the posterior descending artery (PDA) of the right coronary artery, and the marginal branch of the right coronary artery, respectively. Each of these cardiac veins then empties into the coronary sinus on the posterior aspect of the atrioventricular groove (Table 3-10). The coronary sinus empties into the right atrium. Additionally, numerous small cardiac veins (thebesian veins) empty venous blood into all four chambers of the heart.

TABLE 3-10

Coronary Arteries and Cardiac Veins

| VESSEL | COURSE |

| Right coronary artery | Consists of major branches: sinu-atrial (SA) nodal, right marginal, posterior interventricular (posterior descending), atrioventricular (AV) nodal |

| Left coronary artery | Consists of major branches: circumflex, anterior interventricular (left anterior descending [LAD]), left marginal |

| Great cardiac vein | Parallels LAD artery and drains into coronary sinus |

| Middle cardiac vein | Parallels posterior descending artery (PDA), and drains into coronary sinus |

| Small cardiac vein | Parallels right marginal artery and drains into coronary sinus |

| Anterior cardiac veins | Several small veins that drain directly into right atrium |

| Smallest cardiac veins | Drain through the cardiac wall directly into all four heart chambers |

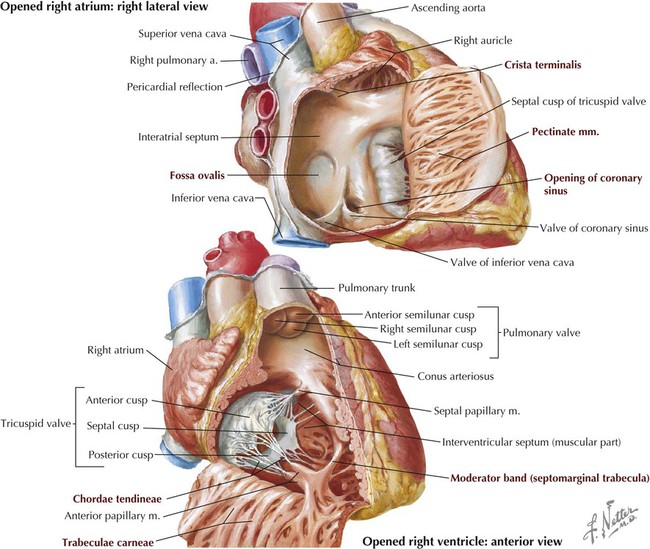

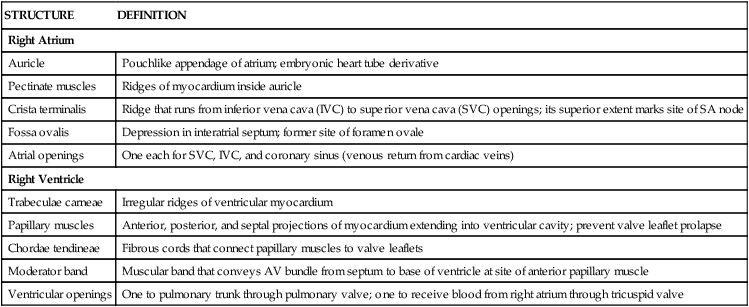

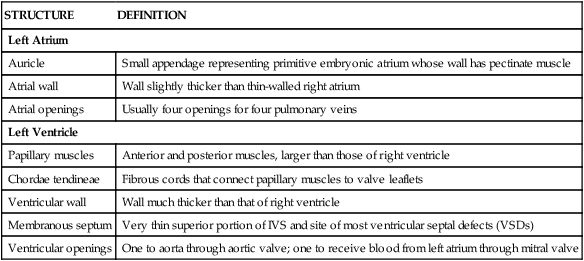

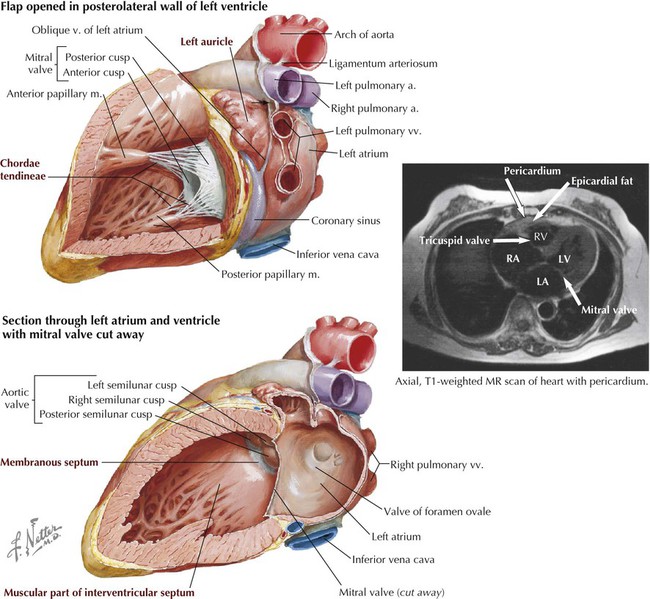

Chambers of the Heart

The human heart has four chambers, each with unique internal features related to their function (Fig. 3-17 and Table 3-11). The right side of the heart is composed of the right atrium and right ventricle. These chambers receive blood from the systemic circulation and pump it to the pulmonary circulation for gas exchange.

TABLE 3-11

General Features of Right Atrium and Right Ventricle

| STRUCTURE | DEFINITION |

| Right Atrium | |

| Auricle | Pouchlike appendage of atrium; embryonic heart tube derivative |

| Pectinate muscles | Ridges of myocardium inside auricle |

| Crista terminalis | Ridge that runs from inferior vena cava (IVC) to superior vena cava (SVC) openings; its superior extent marks site of SA node |

| Fossa ovalis | Depression in interatrial septum; former site of foramen ovale |

| Atrial openings | One each for SVC, IVC, and coronary sinus (venous return from cardiac veins) |

| Right Ventricle | |

| Trabeculae carneae | Irregular ridges of ventricular myocardium |

| Papillary muscles | Anterior, posterior, and septal projections of myocardium extending into ventricular cavity; prevent valve leaflet prolapse |

| Chordae tendineae | Fibrous cords that connect papillary muscles to valve leaflets |

| Moderator band | Muscular band that conveys AV bundle from septum to base of ventricle at site of anterior papillary muscle |

| Ventricular openings | One to pulmonary trunk through pulmonary valve; one to receive blood from right atrium through tricuspid valve |

The left atrium and left ventricle receive blood from the pulmonary circulation and pump it to the systemic circulation (Fig. 3-18 and Table 3-12).

TABLE 3-12

General Features of Left Atrium and Left Ventricle

| STRUCTURE | DEFINITION |

| Left Atrium | |

| Auricle | Small appendage representing primitive embryonic atrium whose wall has pectinate muscle |

| Atrial wall | Wall slightly thicker than thin-walled right atrium |

| Atrial openings | Usually four openings for four pulmonary veins |

| Left Ventricle | |

| Papillary muscles | Anterior and posterior muscles, larger than those of right ventricle |

| Chordae tendineae | Fibrous cords that connect papillary muscles to valve leaflets |

| Ventricular wall | Wall much thicker than that of right ventricle |

| Membranous septum | Very thin superior portion of IVS and site of most ventricular septal defects (VSDs) |

| Ventricular openings | One to aorta through aortic valve; one to receive blood from left atrium through mitral valve |

In both ventricles the papillary muscles and their chordae tendineae provide a structural mechanism that prevents the atrioventricular valves (tricuspid and mitral) from everting (prolapsing) during ventricular systole. The papillary muscles (actually part of the ventricular muscle) contract as the ventricles contract and pull the valve leaflets into alignment. This prevents them from prolapsing into the atrial chamber above as the pressure in the ventricle increases. During ventricular diastole, the muscle relaxes and the tricuspid and mitral valves open normally to facilitate blood flow into the ventricles.

Cardiac Skeleton and Cardiac Valves

The heart has four valves that, along with the myocardium, are attached to fibrous rings of dense collagen that make up the fibrous skeleton of the heart (Fig. 3-19 and Table 3-13). In addition to providing attachment points for the valves, the cardiac skeleton separates the atrial myocardium from the ventricular myocardium (which originate from the fibrous skeleton) and electrically isolates the atria from the ventricles. Only the atrioventricular bundle (of His) conveys electrical impulses between the atria and the ventricles. The following sounds result from valve closure:

TABLE 3-13

| VALVE | CHARACTERISTIC |

| Tricuspid | (Right AV) Between right atrium and right ventricle; has three cusps |

| Pulmonary | (Semilunar) Between right ventricle and pulmonary trunk; has three semilunar cusps (leaflets) |

| Mitral | (Bicuspid) Between left atrium and left ventricle; has two cusps |

| Aortic | (Semilunar) Between left ventricle and aorta; has three semilunar cusps |

Conduction System of the Heart

The heart's conduction system is formed by specialized cardiac muscle cells that form nodes and by unidirectional conduction pathways that initiate and coordinate excitation and contraction of the myocardium (Fig 3-20). The system includes the following four elements:

• Sinu-atrial (SA) node: the “pacemaker” of the heart, where initiation of action potential occurs; located at the superior end of the crista terminalis near the superior vena cava (SVC) opening.

• Atrioventricular (AV) node: the area of the heart that receives impulses from the SA node and conveys them to the common atrioventricular bundle (of His); located between the opening of the coronary sinus and the origin of the septal cusp of the tricuspid valve.

• Common atrioventricular bundle and bundle branches: a collection of specialized heart muscle cells; AV bundle divides into right and left bundle branches, which course down the interventricular septum.

• Subendocardial (Purkinje) system: the ramification of bundle branches in the ventricles of the heart's conduction system; distributes into a subendocardial network of conduction cells that supply the ventricular walls and papillary muscles.

Autonomic Innervation of the Heart

Parasympathetic fibers from the vagus nerve (CN X) course as preganglionic nerves that synapse on postganglionic neurons in the cardiac plexus or within the heart wall itself (Fig. 3-21). Parasympathetic stimulation:

• Decreases the force of contraction.

• Vasodilates coronary resistance vessels (although most vagal effects are restricted directly to the SA node region).

Sympathetic fibers arise from the upper thoracic cord levels (intermediolateral cell column of T1-T4/T5) and enter the sympathetic trunk (Fig. 3-21). These preganglionic fibers synapse in the upper cervical and thoracic sympathetic chain ganglia, and then postganglionic fibers pass to the cardiac plexus. Sympathetic stimulation:

• Increases the force of contraction.

• Minimally vasoconstricts the coronary resistance vessels (via alpha adrenoceptors).

Vasoconstriction, however, is masked by a powerful metabolic coronary vasodilation (mediated by adenosine release from myocytes), which is important because coronary arteries must dilate to supply blood to the heart as it increases its workload.

A bilateral thoracic sympathetic chain of ganglia (sympathetic trunk) passes through the posterior mediastinum across the neck of the upper thoracic ribs and, as it proceeds inferiorly, aligns itself along the lateral bodies of the lower thoracic vertebrae (see also Fig. 4-29). Each of the 11 or 12 ganglia (number varies) is connected to the ventral ramus of the spinal nerve by a white ramus communicans (conveys preganglionic sympathetic fibers from the spinal gray matter to the ganglion) and a gray ramus communicans (conveys postganglionic sympathetic fibers back into the spinal nerve and its ventral and dorsal rami) (see Chapter 1). Additionally, the upper thoracic sympathetic trunk conveys small thoracic cardiac branches (postganglionic sympathetic fibers from the upper thoracic ganglia, T1-T4 or T5) to the cardiac plexus, where they mix with preganglionic parasympathetic fibers from the vagus nerve (Fig. 3-21). Three other pairs of thoracic splanchnic nerves arise from the lower seven thoracic ganglia and send their preganglionic sympathetic fibers inferiorly to abdominal ganglia. The thoracic splanchnic nerves (ganglia levels can vary) (see Chapter 4) include the following:

• Greater splanchnic nerve: usually arises from T5-T9 sympathetic ganglia.

• Lesser splanchnic nerve: usually arises from T10-T11 sympathetic ganglia.

• Least splanchnic nerve: usually arises from T12 sympathetic ganglia.

Visceral afferents for pain are conveyed back to the upper thoracic spinal cord, usually levels T1-T4 or T5, via the sympathetic fiber pathways (see Clinical Focus 3-13). Visceral afferents mediating cardiopulmonary reflexes (stretch receptors, baroreflexes, and chemoreflexes) are conveyed back to the brainstem via the vagus nerve.

6 Mediastinum

The mediastinum (“middle space”) is the middle region of the thoracic cavity and is divided into a superior and an inferior mediastinum by an imaginary horizontal line extending from the sternal angle of Louis to the intervertebral disc between T4 and T5 (Fig. 3-22; see also Fig. 3-1). The superior mediastinum lies behind the manubrium of the sternum, anterior to the first four thoracic vertebrae, and contains the following:

• Thymus gland (largely involuted and replaced by fat in older adults)

The inferior mediastinum is further subdivided as follows (Fig. 3-23):

• Anterior mediastinum: the region posterior to the body of the sternum and anterior to the pericardium (substernal region); contains a variable amount of fat.

• Middle mediastinum: the region containing the pericardium and heart.

• Posterior mediastinum: the region posterior to the heart and anterior to the bodies of the T5-T12 vertebrae; contains the esophagus and its nerve plexus, thoracic aorta, azygos system of veins, sympathetic trunks and thoracic splanchnic nerves, lymphatics, and thoracic duct.

Esophagus and Thoracic Aorta

The esophagus extends from the pharynx (throat) to the stomach and enters the thorax posterior to the trachea. As it descends, the esophagus gradually slopes to the left of the median plane, lying anterior to the thoracic aorta (Fig. 3-24), and pierces the diaphragm at the T10 vertebral level. The esophagus is about 10 cm (4 inches) long and has four points along its course where foreign bodies may become lodged: (1) at its most proximal site at the level of the C6 vertebra (level of the cricoid cartilage), (2) at the point where it is crossed by the aortic arch, (3) at the point where it is crossed by the left main bronchus, and (4) distally at the point where it passes through the diaphragm at the level of the T10 vertebra. The esophagus receives its blood supply from the inferior thyroid artery, esophageal branches of the thoracic aorta, and branches of the left gastric artery (a branch of the celiac trunk in the abdomen).

The thoracic aorta descends alongside and slightly to the left of the esophagus and gives rise to the following arteries before piercing the diaphragm at the T12 vertebral level:

• Pericardial arteries: small arteries that branch from the thoracic aorta and supply the posterior pericardium; variable in number.

• Bronchial arteries: arteries that supply blood to the lungs; usually one artery to the right and two to the left, but variable in number.

• Esophageal arteries: arteries that supply the esophagus; variable in number.

• Mediastinal arteries: small branches that supply the lymph nodes, nerves, and connective tissue of the posterior mediastinum.

• Posterior intercostal arteries: paired arteries that supply blood to the lower nine intercostal spaces.

• Superior phrenic arteries: small arteries to the superior surface of the diaphragm; anastomose with the musculophrenic and pericardiacophrenic arteries (which arise from the internal thoracic artery).

• Subcostal arteries: paired arteries that lie below the inferior margin of the last rib; anastomose with superior epigastric, lower intercostal, and lumbar arteries.

Azygos System of Veins

The azygos venous system drains the posterior thorax and forms an important venous conduit between the inferior and the superior vena cava (IVC and SVC) (Fig. 3-25). This system represents the deep venous drainage characteristic of veins throughout the body. Its branches, although variable, largely drain the same regions supplied by the thoracic aorta's branches described earlier. The key veins include the azygos vein, with its right ascending lumbar, subcostal, and intercostal tributaries (sometimes the azygos vein also arises from the IVC before the ascending lumbar and subcostal tributaries join it), the hemi-azygos vein, and the accessory hemi-azygos vein. (If present, it usually begins at the fourth intercostal space.) A small left superior intercostal vein (a tributary of the left brachiocephalic vein) may also connect with the hemi-azygos vein. Ultimately, most of the thoracic venous drainage passes into the azygos vein, which ascends right of the midline to empty into the SVC.

Arteriovenous Overview

Arteries of the Thoracic Aorta (Fig. 3-26)

The heart (1) gives rise to the ascending aorta (2), which receives blood from the left ventricle. The right and left coronary arteries immediately arise from the aorta and supply the heart itself. The aortic arch (3) connects the ascending aorta and the descending aorta (4) and is found in the superior mediastinum. The descending aorta then continues inferiorly as the thoracic aorta (5). The thoracic aorta gives rise to branches to the lungs, esophagus, pericardium, mediastinum, diaphragm, and posterior intercostal branches to the thoracic wall. The posterior intercostal arteries course along the inferior aspect of each rib (in the costal groove) and supply spinal branches (to thoracic vertebrae and thoracic spinal cord), lateral branches, and branches to the mammary glands. The intercostals anastomose with the anterior intercostal branches from the internal thoracic artery, a branch of the subclavian artery (see Fig. 8-64). The thoracic aorta lies to the left of the thoracic vertebral bodies as it descends in the thorax, so the left intercostals are shorter than the right intercostal arteries. As it approaches the diaphragm, the aorta then shifts closer to the midline of the lower thoracic vertebrae. The lower portion of the esophagus passes anterior to the lower portion of the thoracic aorta (5) on its way to the diaphragm and stomach. The thoracic aorta pierces the diaphragm at the level of the T12 vertebra and passes through the aortic hiatus to enter the abdominal cavity. The aortic arch gives off very small branches to the aortic body chemoreceptors (not listed in the outline; function similar to the carotid body chemoreceptors).

Veins of the Thorax (Fig. 3-27)

The venous drainage begins with the vertebral venous plexus draining the vertebral column and spinal cord. This plexus includes both an internal and an external vertebral venous plexus. While most of these veins are valveless, recent evidence suggests that some valves do exist in variable numbers in some of these veins. The posterior intercostal veins parallel the posterior intercostal arteries as the veins course in the costal groove at the inferior margin of each rib. The intercostal veins drain largely into hemi-azygos veins (2) and azygos veins (3) in the posterior mediastinum. An ascending lumbar vein from the upper abdominal cavity collects venous blood segmentally and often from the left renal vein; it is an important connection between these abdominal caval veins and the azygos system in the thorax. A number of mediastinal veins exist in the posterior mediastinum and drain the diaphragm, pericardium, esophagus, and main bronchi. These veins ultimately drain into the accessory hemi-azygos veins (1) and hemia-zygos veins just to the left of the thoracic vertebral bodies or into the azygos vein just to the right of the vertebral bodies. About midway in the thorax, the hemi-azygos vein crosses the midline and drains into the azygos vein, although the hemi-azygos usually maintains its connection with the accessory hemi-azygos vein as well. Veins tend to connect with one another where possible, and many connections are small, variable, and not readily recognizable. The azygos vein delivers venous blood to the superior vena cava (4) just before the SVC enters the right atrium of the heart (5). The accessory hemi-azygos vein also often has connections with the left brachiocephalic vein, providing another venous pathway back to the right side of the heart. Flow in the azygos system of veins is pressure dependent and, being essentially valveless veins, the flow can go in either direction. As with other regional veins, the number of veins of the azygos system can be variable.

Mediastinal Lymphatics

The thoracic lymphatic duct begins in the abdomen at the cisterna chyli (found between the abdominal aorta and the right crus of the diaphragm), ascends through the posterior mediastinum posterior to the esophagus, crosses to the left of the median plane at approximately the T5-T6 vertebral level, and empties into the venous system at the junction of the left internal jugular and left subclavian veins (Fig. 3-28).

7 Embryology

Respiratory System

The airway and lungs begin developing during the fourth week of gestation. Key features of this development include the following (Fig. 3-29):

• Formation of the laryngotracheal diverticulum from the ventral foregut, just inferior to the last pair of pharyngeal pouches

• Division of the laryngotracheal diverticulum into the left and right lung (bronchial) buds, each with a primary bronchus

• Division of the lung buds to form the definitive lobes of the lungs (three lobes in the right lung, two lobes in the left lung)

• Formation of segmental bronchi and 10 bronchopulmonary segments in each lung (by weeks 6 to 7)

The airway passages are lined by epithelium derived from the endoderm of the foregut, while mesoderm forms the stroma of each lung. By 6 months of gestation, the alveoli are mature enough for gas exchange, but the production of surfactant, which reduces surface tension and helps prevent alveolar collapse, may not be sufficient to support respiration. A premature infant's ability to keep its airways open often is the limiting factor if the premature birth occurs before adequate surfactant cells (type II pneumocytes) are present.

Early Embryonic Vasculature

Toward the end of the third week of development, the embryo establishes a primitive vascular system to meet its growing needs for oxygen and nutrients (Fig. 3-30). Blood leaving the embryonic heart enters a series of paired arteries called the aortic arches, which are associated with the pharyngeal arches. The blood then flows from these arches into the single midline aorta (formed by the fusion of two dorsal aortae), coursing along the length of the embryo. Some of the blood enters the vitelline arteries to supply the future bowel (still the yolk sac at this stage), and some passes to the placenta via a pair of umbilical arteries, where gases, nutrients, and metabolic wastes are exchanged.

Blood returning from the placenta is oxygenated and carries nutrients back to the heart through the single umbilical vein. Blood also returns to the heart through the following veins:

Aortic Arches

Blood pumped from the primitive embryonic heart passes into aortic arches that are associated with the pharyngeal arches (Fig. 3-31). The right and left dorsal aortas caudal to the pharyngeal arches fuse to form the single midline aorta, while the aortic arches give rise to the arteries summarized in Table 3-14.

TABLE 3-14

| ARCH | DERIVATIVE |

| 1 | Largely disappears (part of maxillary artery in head) |

| 2 | Largely disappears |

| 3 | Common and internal carotid arteries |

| 4 | Right subclavian artery and aortic arch (on left side) |

| 5 | Disappears |

| 6 | Ductus arteriosus and proximal part of pulmonary arteries |

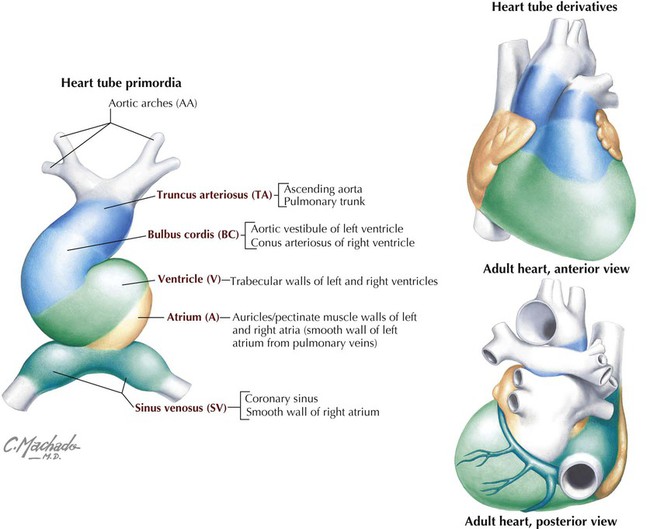

Development of Embryonic Heart Tube and Heart Chambers

The primitive heart begins its development as a single unfolded tube, much like an artery develops (Fig. 3-32). The heart tube receives blood from the embryonic body, which passes through its heart tube segments in the following sequence:

• Sinus venosus: receives all the venous return from the embryonic body and placenta to the heart tube.

• Atrium: receives blood from the sinus venosus and passes it to the ventricle.

• Ventricle: receives atrial blood and passes it to the bulbus cordis.

• Bulbus cordis: receives ventricular blood and passes it to the truncus arteriosus.

• Truncus arteriosus: receives blood and passes it to the aortic arch system for distribution to the body.

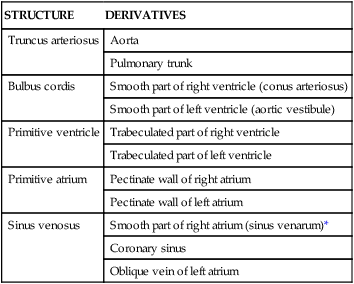

This primitive heart tube soon begins to fold on itself in an “S-bend.” The ventricle folds downward and to the right, and the atrium and sinus venosus fold upward and to the left, thus forming the definitive positions of the heart's future chambers (atria and ventricles) (Fig. 3-32 and Table 3-15).

TABLE 3-15

Adult Heart Derivatives of Embryonic Heart Tube

| STRUCTURE | DERIVATIVES |

| Truncus arteriosus | Aorta |

| Pulmonary trunk | |

| Bulbus cordis | Smooth part of right ventricle (conus arteriosus) |

| Smooth part of left ventricle (aortic vestibule) | |

| Primitive ventricle | Trabeculated part of right ventricle |

| Trabeculated part of left ventricle | |

| Primitive atrium | Pectinate wall of right atrium |

| Pectinate wall of left atrium | |

| Sinus venosus | Smooth part of right atrium (sinus venarum)* |

| Coronary sinus | |

| Oblique vein of left atrium |

*The smooth part of the left atrium is formed by incorporation of parts of the pulmonary veins into the atrial wall. The junction of the pectinated and smooth parts of the right atrium is called the crista terminalis.

From Dudek R: High-yield embryology: a collaborative project of medical students and faculty, Philadelphia, 2006, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

The four chambers of the heart (two atria and two ventricles) are formed by the internal septation of the single atrium and ventricle of the primitive heart tube. Because most of the blood does not perfuse the lungs in utero (the lungs are filled with amniotic fluid and are partially collapsed), blood in the right atrium passes directly to the left atrium via a small opening in the interatrial septum called the foramen ovale. The interatrial septum is formed by the fusion of a septum primum and a septum secundum (develops on the right atrial side of the septum primum) (Fig. 3-33). This fusion occurs after birth when the left atrial pressure exceeds that of the right atrium (blood now passes into the lungs and returns to the left atrium, raising the pressure on the left side) and pushes the two septae together, thus forming the fossa ovalis of the postnatal heart. The ventricular septum forms from the superior growth of the muscular interventricular septum from the base of the heart toward the downward growth of a thin membranous septum from the endocardial cushion (Fig. 3-34). Simultaneously, the bulbus cordis and truncus arteriosus form the outflow tracts of the ventricles, pulmonary trunk, and aorta.

Fetal Circulation

The pattern of fetal circulation is one of gas exchange and nutrient/metabolic waste exchange across the placenta with the maternal blood (but not the exchange of blood cells), and distribution of oxygen and nutrient-rich blood to the tissues of the fetus (Fig. 3-35). Various shunts allow fetal blood to bypass the liver (not needed for metabolic processing in utero) and lungs (not needed for gas exchange in utero) so that the blood may gain direct access to the left side of the heart and be pumped into the fetal arterial system. At or shortly after birth, these shunts close, resulting in the normal pattern of pulmonary and systemic circulation.