Abdomen

1 Introduction

The abdomen is the region between the thorax superiorly and the pelvis inferiorly. The abdomen is composed of the following:

• Layers of skeletal muscle that line the abdominal walls and assist in respiration and, by increasing intraabdominal pressure, facilitate micturition (urination), defecation (bowel movement), and childbirth.

• The abdominal cavity, a peritoneal lined cavity that is continuous with the pelvic cavity inferiorly and contains the abdominal viscera (organs).

• Visceral structures that lie within the abdominal peritoneal cavity (intraperitoneal) and include the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and its associated organs, the spleen, and the urinary system (kidneys and ureters), which is located retroperitoneally behind and outside the cavity but anterior to the posterior abdominal wall muscles.

In your study of the abdomen, first focus on the abdominal wall and note the continuation of the three muscle layers of the thorax (intercostal muscles) as they blend into the abdominal flank musculature.

Next, note the disposition of the abdominal organs. For example, you should know the region or quadrant of the abdominal cavity in which the organs reside; whether an organ is suspended in a mesentery or lies retroperitoneally (refer to embryology of abdominal viscera, i.e., foregut, midgut, or hindgut derivatives); the blood supply and autonomic innervation pattern to the organs; and features of the organs that will allow you to readily identify which organ or part of an organ you are viewing (particularly important in laparoscopic surgery). Also, you should understand the dual venous drainage of the abdomen by the caval and hepatic portal systems and the key anastomoses between these two systems that facilitate venous return to the heart.

Lastly, study the posterior abdominal wall musculature, and identify the components and distribution of the lumbar plexus of somatic nerves.

2 Surface Anatomy

Key Landmarks

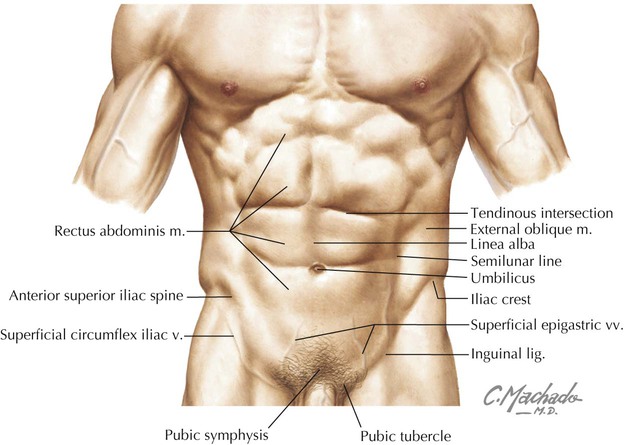

Key surface anatomy features of the anterolateral abdominal wall include the following (Fig. 4-1):

• Rectus sheath: a fascial sheath containing the rectus abdominis muscle, which runs from the pubic symphysis and crests to the xiphoid process and fifth to seventh costal cartilages.

• Linea alba: literally the “white line”; a relatively avascular midline subcutaneous band of fibrous tissue where the fascial aponeuroses of the rectus sheath from each side interdigitate in the midline.

• Semilunar line: the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle in the rectus sheath.

• Tendinous intersections: transverse skin grooves that demarcate transverse fibrous attachment points of the rectus sheath to the underlying rectus abdominis muscle.

• Umbilicus: the site that marks the T10 dermatome, lying at the level of the intervertebral disc between L3 and L4; the former attachment site of the umbilical cord.

• Iliac crest: the rim of the ilium, which lies at about the level of the L4 vertebra.

• Inguinal ligament: a ligament composed of the aponeurotic fibers of the external abdominal oblique muscle, which lies deep to a skin crease that marks the division between the lower abdominal wall and thigh of the lower limb.

Surface Topography

Clinically, the abdominal wall is divided descriptively into quadrants or regions so that both the underlying visceral structures and the pain or pathology associated with these structures can be localized and topographically described. Common clinical descriptions use either quadrants or the nine descriptive regions, demarcated by two vertical midclavicular lines and two horizontal lines: the subcostal and intertubercular planes (Fig. 4-2 and Table 4-1).

TABLE 4-1

Clinical Planes of Reference for Abdomen

| PLANE OF REFERENCE | DEFINITION |

| Median | Vertical plane from xiphoid process to pubic symphysis |

| Transumbilical | Horizontal plane across umbilicus; these planes divide the abdomen into quadrants. |

| Subcostal | Horizontal plane across inferior margin of 10th costal cartilage |

| Intertubercular | Horizontal plane across tubercles of ilium and body of L5 vertebra |

| Midclavicular | Two vertical planes through midpoint of clavicles; these planes divide the abdomen into nine regions. |

3 Anterolateral Abdominal Wall

Layers

The layers of the abdominal wall include the following:

• Superficial fascia (subcutaneous tissue): a single, fatty connective tissue layer below the level of the umbilicus that divides into a more superficial fatty layer (Camper's fascia) and a deeper membranous layer (Scarpa's fascia; see Fig. 4-11).

• Investing fascia: tissue that covers the muscle layers.

• Abdominal muscles: three flat layers, similar to the thoracic wall musculature, except in the anterior midregion where the vertically oriented rectus abdominis muscle lies in the rectus sheath.

• Endoabdominal fascia: tissue that is unremarkable except for a thicker portion called the transversalis fascia, which usually lines the inner aspect of the transversus abdominis muscle; it is continuous with fascia on the underside of the diaphragm, fascia of the posterior abdominal muscles, and fascia of the pelvic muscles.

• Extraperitoneal (fascia) fat: connective tissue that is variable in thickness and contains a variable amount of fat.

• Peritoneum: thin serous membrane that lines the inner aspect of the abdominal wall (parietal peritoneum) and occasionally reflects off the walls as a mesentery to invest partially or completely various visceral structures (visceral peritoneum).

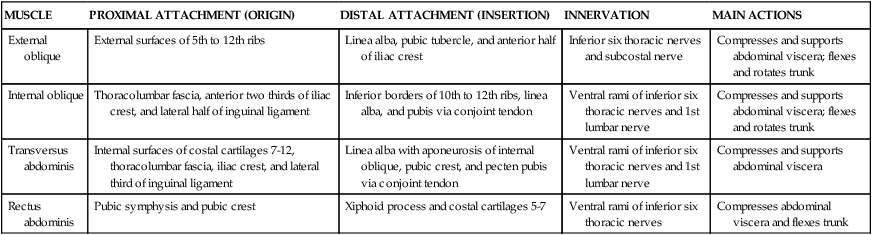

Muscles

The muscles of the anterolateral abdominal wall include three flat layers that are continuations of the three layers in the thoracic wall (Fig. 4-3). These include two abdominal oblique muscles and the transversus abdominis muscle (Table 4-2). In the midregion a vertically oriented pair of rectus abdominis muscles lies within the rectus sheath and extends from the pubic symphysis and crest to the xiphoid process and costal cartilages 5 to 7 superiorly. The small pyramidalis muscle (Fig. 4-3, B) is inconsistent and clinically insignificant.

TABLE 4-2

Principal Muscles of Anterolateral Abdominal Wall

| MUSCLE | PROXIMAL ATTACHMENT (ORIGIN) | DISTAL ATTACHMENT (INSERTION) | INNERVATION | MAIN ACTIONS |

| External oblique | External surfaces of 5th to 12th ribs | Linea alba, pubic tubercle, and anterior half of iliac crest | Inferior six thoracic nerves and subcostal nerve | Compresses and supports abdominal viscera; flexes and rotates trunk |

| Internal oblique | Thoracolumbar fascia, anterior two thirds of iliac crest, and lateral half of inguinal ligament | Inferior borders of 10th to 12th ribs, linea alba, and pubis via conjoint tendon | Ventral rami of inferior six thoracic nerves and 1st lumbar nerve | Compresses and supports abdominal viscera; flexes and rotates trunk |

| Transversus abdominis | Internal surfaces of costal cartilages 7-12, thoracolumbar fascia, iliac crest, and lateral third of inguinal ligament | Linea alba with aponeurosis of internal oblique, pubic crest, and pecten pubis via conjoint tendon | Ventral rami of inferior six thoracic nerves and 1st lumbar nerve | Compresses and supports abdominal viscera |

| Rectus abdominis | Pubic symphysis and pubic crest | Xiphoid process and costal cartilages 5-7 | Ventral rami of inferior six thoracic nerves | Compresses abdominal viscera and flexes trunk |

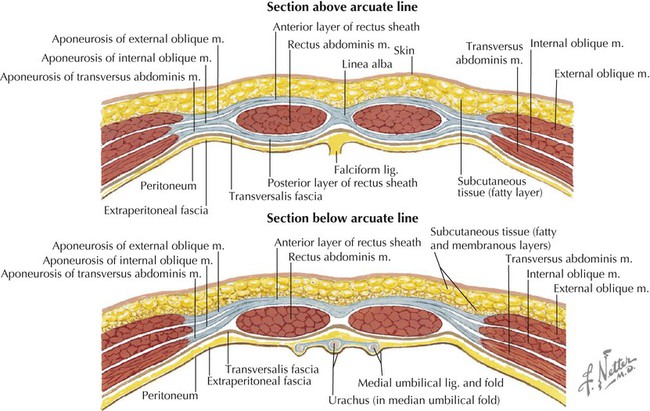

Rectus Sheath

The rectus sheath encloses the vertically running rectus abdominis muscle (and inconsistent pyramidalis), the superior and inferior epigastric vessels, the lymphatics, and the ventral rami of T7-L1 nerves, which enter the sheath along its lateral margins (Fig. 4-3, C). The superior three quarters of the rectus abdominis is completely enveloped within the rectus sheath, and the inferior one quarter is supported posteriorly only by the transversalis fascia, extraperitoneal fat, and peritoneum; the site of this transition is called the arcuate line (Fig. 4-4 and Table 4-3).

TABLE 4-3

Aponeuroses and Layers Forming Rectus Sheath*

| LAYER | COMMENT |

| Anterior lamina above arcuate line | Formed by fused aponeuroses of external and internal abdominal oblique muscles |

| Posterior lamina above arcuate line | Formed by fused aponeuroses of internal abdominal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles |

| Below arcuate line | All three muscle aponeuroses fuse to form anterior lamina, with rectus abdominis in contact only with transversalis fascia posteriorly |

*See Figure 4-4.

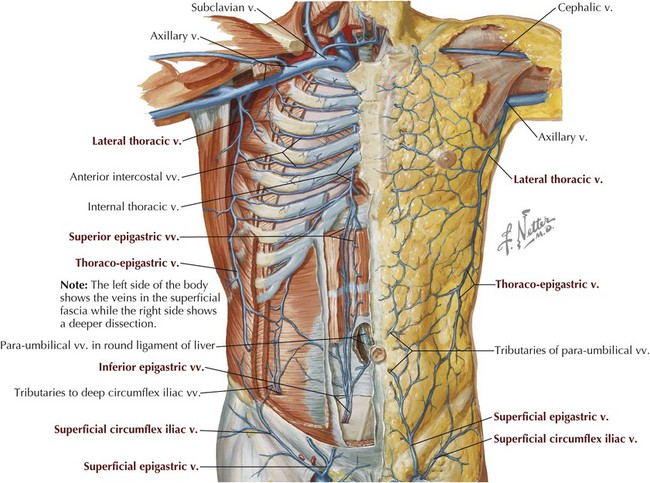

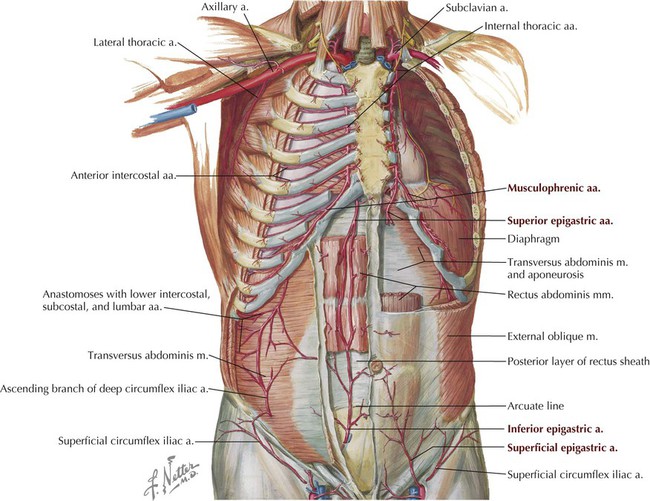

Innervation and Blood Supply

The segmental innervation of the anterolateral abdominal skin and muscles is by ventral rami of T7-L1. The blood supply includes the following arteries (Figs. 4-3, C, and 4-5):

• Musculophrenic: a terminal branch of the internal thoracic artery that courses along the costal margin.

• Superior epigastric: arises from the terminal end of the internal thoracic artery and anastomoses with the inferior epigastric artery at the level of the umbilicus.

• Inferior epigastric: arises from the external iliac artery and anastomoses with the superior epigastric artery.

• Superficial circumflex iliac: arises from the femoral artery and anastomoses with the deep circumflex iliac artery.

• Superficial epigastric: arises from the femoral artery and courses toward the umbilicus.

• External pudendal: arises from the femoral artery and courses toward the pubis.

Superficial and deeper veins accompany these arteries, but, as elsewhere in the body, they form extensive anastomoses with each other to facilitate venous return to the heart (Fig. 4-6 and Table 4-4).

TABLE 4-4

Principal Veins of Anterolateral Abdominal Wall

| VEIN | COURSE |

| Superficial epigastric | Drains into femoral vein |

| Superficial circumflex iliac | Drains into femoral vein and parallels inguinal ligament |

| Inferior epigastric | Drains into external iliac vein |

| Superior epigastric | Drains into internal thoracic vein |

| Thoraco-epigastric | Anastomoses between superficial epigastric and lateral thoracic |

| Lateral thoracic | Drains into axillary vein |

Lymphatic drainage of the abdominal wall parallels the venous drainage, with the lymph ultimately coursing to the following lymph node collections:

• Axillary nodes: superficial drainage above the umbilicus

• Superficial inguinal nodes: superficial drainage below the umbilicus

• Parasternal nodes: deep drainage along the internal thoracic vessels

• Lumbar nodes: deep drainage internally to the nodes along the abdominal aorta

• External iliac nodes: deep drainage along the external iliac vessels

4 Inguinal Region

The inguinal region, or groin, is the transition zone between the lower abdomen and the upper thigh. This region, especially in males, is characterized by a weakened area of the lower abdominal wall that renders this region particularly susceptible to inguinal hernias. Although occurring in either gender, inguinal hernias are much more common in males because of the descent of the testes into the scrotum, which occurs along this boundary region.

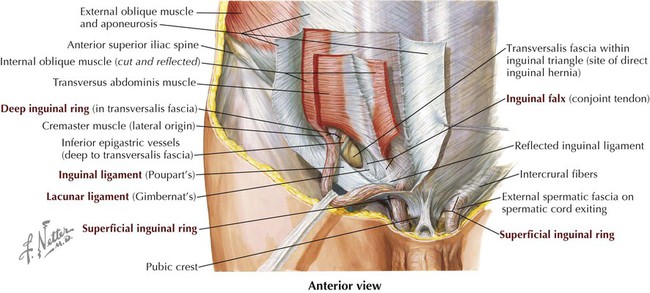

The inguinal region is demarcated by the inguinal ligament, the inferior border of the external abdominal oblique aponeurosis, which is folded under on itself and attaches to the anterior superior iliac spine and extends inferomedially to attach to the pubic tubercle (see Figs. 4-1 and 4-3, B). Medially, the inguinal ligament flares into the crescent-shaped lacunar ligament that attaches to the pecten pubis of the pubic bone (Fig. 4-7). Fibers from the lacunar ligament also course internally along the pelvic brim as the pectineal ligament (see Clinical Focus 4-2). A thickened inferior margin of the transversalis fascia, called the iliopubic tract, runs parallel to the inguinal ligament but deep to it and reinforces the medial portion of the inguinal canal.

Inguinal Canal

The gonads in both genders initially develop retroperitoneally from a mass of intermediate mesoderm called the urogenital ridge. As the gonads begin to descend toward the pelvis, a peritoneal pouch called the processus vaginalis extends through the various layers of the anterior abdominal wall and acquires a covering from each layer, except for the transversus abdominis muscle because the pouch passes beneath this muscle layer. The processus vaginalis and its coverings form the fetal inguinal canal, a tunnel or passageway through the anterior abdominal wall. In females the ovaries are attached to the gubernaculum, the other end of which terminates in the labioscrotal swellings (which will form the labia majora in females or the scrotum in males). The ovaries descend into the pelvis, where they remain, tethered between the lateral pelvic wall and the uterus medially (by the ovarian ligament, a derivative of the gubernaculum). The gubernaculum then reflects off the uterus as the round ligament of the uterus, passes through the inguinal canal, and ends as a fibrofatty mass in the future labia majora.

In males the testes descend into the pelvis but then continue their descent through the inguinal canal (formed by the processus vaginalis) and into the scrotum, which is the male homologue of the female labia majora (Fig. 4-8). This descent through the inguinal canal occurs around the 26th week of development, usually over several days. The gubernaculum terminates in the scrotum and anchors the testis to the floor of the scrotum. A small pouch of the processus vaginalis called the tunica vaginalis persists and partially envelops the testis. In both genders the processus vaginalis then normally seals itself and is obliterated. Sometimes this fusion does not occur or is incomplete, especially in males, probably caused by descent of the testes through the inguinal canal. Consequently, a weakness may persist in the abdominal wall that can lead to inguinal hernias.

As the testes descend, they bring their accompanying spermatic cord along with them and, as these structures pass through the inguinal canal, they too become ensheathed within the layers of the anterior abdominal wall (Fig. 4-9). The spermatic cord enters the inguinal canal at the deep inguinal ring (an outpouching in the transversalis fascia lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels) and exits the 4-cm-long canal via the superficial inguinal ring (superior to the pubic tubercle) before passing into the scrotum, where it suspends the testis. In females the only structure in the inguinal canal is the fibrofatty remnant of the round ligament of the uterus, which terminates in the labia majora. The contents in the spermatic cord include the following (Fig. 4-9):

• Testicular artery, artery of the ductus deferens, and cremasteric artery

• Pampiniform plexus of veins (testicular veins)

• Autonomic nerve fibers (sympathetic efferents and visceral afferents) coursing on the arteries and ductus deferens

• Genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve (innervates cremaster muscle)

Layers of the spermatic cord include the following (see Fig. 4-9):

• External spermatic fascia: derived from the external abdominal oblique aponeurosis

• Cremasteric (middle spermatic) fascia: derived from the internal abdominal oblique muscle

• Internal spermatic fascia: derived from the transversalis fascia

The features of the inguinal canal include its anatomical boundaries, as shown in Figure 4-10 and summarized in Table 4-5. Note that the deep inguinal ring begins internally as an outpouching of the transversalis fascia lateral to the inferior epigastric vessels, and that the superficial inguinal ring is the opening in the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle. Aponeurotic fibers at the superficial ring envelop the emerging spermatic cord medially (medial crus), over its top (intercrural fibers), and laterally (lateral crus) (Fig. 4-10).

TABLE 4-5

Features and Boundaries of Inguinal Canal

| FEATURE | COMMENT |

| Superficial ring | Medial opening in external abdominal oblique aponeurosis |

| Deep ring | Evagination of transversalis fascia lateral to inferior epigastric vessels, forming internal layer of spermatic fascia |

| Inguinal canal | Tunnel extending from deep to superficial ring, paralleling inguinal ligament; transmits spermatic cord in males or round ligament of uterus in females) |

| Anterior wall | Aponeuroses of external and internal abdominal oblique muscles |

| Posterior wall | Transversalis fascia; medially includes conjoint tendon |

| Roof | Arching muscle fibers of internal abdominal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles |

| Floor | Medial half of inguinal ligament, and medially by lacunar ligament, an expanded extension of the ligament |

| Inguinal ligament | Ligament extending between anterior superior iliac spine and pubic tubercle; folded inferior border of external abdominal oblique aponeurosis |

5 Abdominal Viscera

Peritoneal Cavity

The abdominal viscera are contained within a serous membrane–lined recess called the abdominopelvic cavity (sometimes just “abdominal” or “peritoneal” cavity) or lie in a retroperitoneal position adjacent to this cavity, often with only their anterior surface covered by peritoneum (e.g., the kidneys and ureters). The abdominopelvic cavity extends from the abdominal diaphragm inferiorly to the floor of the pelvis (Fig. 4-11).

Observe the parietal peritoneum lining the cavity walls, the mesenteries suspending various portions of the viscera, and the lesser and greater sacs. (From Atlas of human anatomy, ed 6, Plate 321.)

The walls of the abdominopelvic cavity are lined by parietal peritoneum, which can reflect off the abdominal walls in a double layer called a mesentery, which embraces and suspends a visceral structure. As the mesentery wraps around the viscera, it becomes visceral peritoneum. Viscera suspended by a mesentery are considered intraperitoneal, whereas viscera covered on only one side by peritoneum are considered retroperitoneal.

The parietal peritoneum lines the inner aspect of the abdominal wall and thus is innervated by somatic afferent fibers of the ventral rami of the spinal nerves innervating the abdominal musculature. Inflammation or trauma to the parietal peritoneum therefore presents as well-localized pain. The visceral peritoneum, on the other hand, is innervated by visceral afferent fibers carried in the sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves. Pain associated with visceral peritoneum thus is more poorly localized, giving rise to referred pain (see Table 4-12).

Anatomists refer to the peritoneal cavity as a “potential space” because it normally contains only a small amount of serous fluid that lubricates its surface. If excessive fluid collects in this space because of edema (ascites) or hemorrhage, it becomes a “real space.” Many clinicians, however, view the cavity only as a real space because it does contain serous fluid, although they qualify this distinction further when ascites or hemorrhage occurs.

The abdominopelvic cavity is further subdivided into the following (Figs. 4-11 and 4-12):

• Greater sac: most of the abdominopelvic cavity

• Lesser sac: also called the omental bursa; an irregular part of the peritoneal cavity that forms a cul-de-sac space posterior to the stomach and anterior to the retroperitoneal pancreas; it communicates with the greater sac via the epiploic foramen (of Winslow).

In addition to the mesenteries that suspend the bowel, the peritoneal cavity contains a variety of double-layered folds of peritoneum, including the omenta (attached to the stomach) and peritoneal ligaments. These are not “ligaments” in the traditional sense but rather short, distinct mesenteries that connect structures (for which they are named) together or to the abdominal wall (Table 4-6). Some of these structures are shown in Figures 4-11 and 4-12, and we will encounter the others later in the chapter as we describe the abdominal contents.

TABLE 4-6

Mesenteries, Omenta, and Peritoneal Ligaments

| FEATURE | DESCRIPTION |

| Greater omentum | “Apron” of peritoneum hanging from greater curvature of stomach, folding back on itself and attaching to transverse colon |

| Lesser omentum | Double layer of peritoneum extending from lesser curvature of stomach and proximal duodenum to inferior surface of liver |

| Mesenteries | Double fold of peritoneum suspending parts of bowel and conveying vessels, lymphatics, and nerves of bowel (meso-appendix, transverse mesocolon, sigmoid mesocolon) |

| Peritoneal ligaments | Double layer of peritoneum attaching viscera to walls or to other viscera |

| Gastrocolic ligament | Portion of greater omentum that extends from greater curvature of stomach to transverse colon |

| Gastrosplenic ligament | Left part of greater omentum that extends from hilum of spleen to greater curvature of stomach |

| Splenorenal ligament | Connects spleen and left kidney |

| Gastrophrenic ligament | Portion of greater omentum that extends from fundus to diaphragm |

| Phrenocolic ligament | Extends from left colic flexure to diaphragm |

| Hepatorenal ligament | Connects liver to right kidney |

| Hepatogastric ligament | Portion of lesser omentum that extends from liver to lesser curvature of stomach |

| Hepatoduodenal ligament | Portion of lesser omentum that extends from liver to 1st part of duodenum |

| Falciform ligament | Extends from liver to anterior abdominal wall |

| Ligamentum teres hepatis | Obliterated left umbilical vein in free margin of falciform ligament |

| Coronary ligaments | Reflections of peritoneum from superior aspect of liver to diaphragm |

| Ligamentum venosum | Fibrous remnant of obliterated ductus venosus |

| Suspensory ligament of ovary | Extends from lateral pelvic wall to ovary |

| Ovarian ligament | Connects ovary to uterus (part of gubernaculum) |

| Round ligament of uterus | Extends from uterus to deep inguinal ring (part of gubernaculum) |

Abdominal Organs

Abdominal Esophagus and Stomach

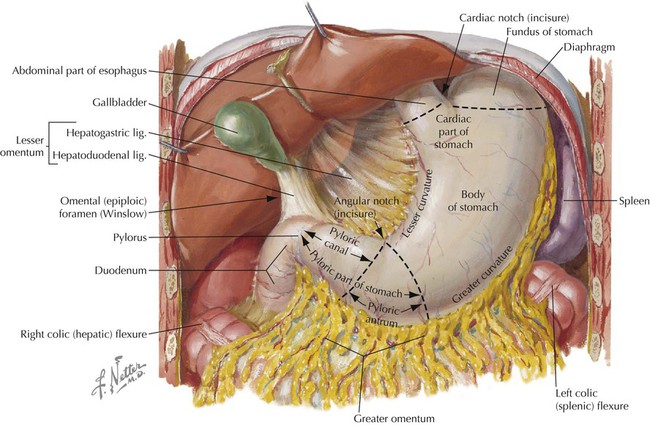

The distal end of the esophagus passes through the right crus of the abdominal diaphragm at about the level of the T10 vertebra and terminates in the cardiac portion of the stomach (Fig. 4-13).

The stomach is a dilated, saclike portion of the GI tract that exhibits significant variation in size and configuration, terminating at the thick, smooth muscle sphincter (pyloric sphincter) by joining the first portion of the duodenum. The stomach is tethered superiorly by the lesser omentum (gastrohepatic ligament portion; Table 4-6) extending from its lesser curvature and is attached along its greater curvature to the greater omentum and the gastrosplenic ligament (see Figs. 4-12 and 4-13). Generally, the J-shaped stomach is divided into the following regions (Fig. 4-13 and Table 4-7):

TABLE 4-7

Descriptive Features of the Stomach

| FEATURE | DESCRIPTION |

| Lesser curvature | Right border of stomach; lesser omentum attaches here and extends to liver |

| Greater curvature | Convex border with greater omentum suspended from its margin |

| Cardiac part | Area of stomach that communicates with esophagus superiorly |

| Fundus | Superior part just under left dome of diaphragm |

| Body | Main part between fundus and pyloric antrum |

| Pyloric part | Portion divided into proximal antrum and distal canal |

| Pylorus | Site of pyloric sphincter muscle; joins 1st part of duodenum |

The interior of the unstretched stomach is lined with prominent longitudinal mucosal gastric folds called rugae, which become more evident as they approach the pyloric region. As an embryonic foregut derivative, the stomach's blood supply comes from the celiac trunk and its major branches (see Embryology).

Small Intestine

The small intestine measures about 6 meters in length (somewhat shorter in the fixed cadaver) and is divided into the following three parts:

• Duodenum: about 25 cm long and largely retroperitoneal

• Jejunum: about 2.5 meters long and suspended by a mesentery

The duodenum is the first portion of the small intestine and descriptively is divided into four parts (Table 4-8). Most of the C-shaped duodenum is retroperitoneal and ends at the duodenojejunal flexure, where it is tethered by a musculoperitoneal fold called the suspensory ligament of the duodenum (ligament of Treitz) (Fig. 4-14).

TABLE 4-8

| PART OF DUODENUM | DESCRIPTION |

| Superior | First part; attachment site for hepatoduodenal ligament of lesser omentum; technically not retroperitoneal for the first 1 or 2 inches (2.5-5 cm) |

| Descending | Second part; site where bile and pancreatic ducts empty |

| Inferior | Third part; crosses inferior vena cava and aorta and is crossed anteriorly by mesenteric vessels |

| Ascending | Fourth part; tethered by suspensory ligament at duodenojejunal flexure |

The jejunum and ileum are both suspended in an elaborate mesentery. The jejunum is recognizable from the ileum because the jejunum (Fig. 4-15):

• Occupies the left upper quadrant of the abdomen.

• Is larger in diameter than the ileum.

• Has mesentery with less fat.

• Has arterial branches with fewer arcades and longer vasa recta.

• Internally has mucosal folds that are higher and more numerous, which increases the surface area for absorption.

The small intestine ends at the ileocecal junction, where a sphincter called the ileocecal valve controls the passage of ileal contents into the cecum (Fig. 4-16). The valve is actually two internal mucosal folds that cover a thickened smooth muscle sphincter.

The small intestine is a derivative of the embryonic midgut and receives its arterial supply from the superior mesenteric artery and its branches. An exception to this generalization is the first part of the duodenum, and sometimes the second part, which receives arterial blood from the gastroduodenal branch (from the common hepatic artery of the celiac trunk). This overlap reflects the embryonic transition from the foregut and midgut derivatives (stomach to first portions of duodenum).

Large Intestine

The large intestine is about 1.5 meters long, extending from the cecum to the anal canal, and includes the following segments (Figs. 4-16 and 4-17):

• Cecum: a pouch that is connected to the ascending colon and the ileum; it extends below the ileocecal junction, although it is not suspended by a mesentery.

• Appendix: a narrow tube of variable length (usually 7-10 cm) that contains numerous lymphoid nodules and is suspended by mesentery called the meso-appendix.

• Ascending colon: is retroperitoneal and ascends on the right flank to reach the liver, where it bends into the right colic (hepatic) flexure.

• Transverse colon: is suspended by a mesentery, the transverse mesocolon, and runs transversely from the right hypochondrium to the left, where it bends to form the left colic (splenic) flexure.

• Descending colon: is retroperitoneal and descends along the left flank to join the sigmoid colon in the left groin region.

• Sigmoid colon: is suspended by a mesentery, the sigmoid mesocolon, and forms a variable loop of bowel that runs medially to join the midline rectum in the pelvis.

• Rectum and anal canal: are retroperitoneal and extend from the middle sacrum to the anus (see Chapter 5).

Lateral to the ascending and the descending colon lie the right and the left paracolic gutters, respectively. These depressions provide conduits for abdominal fluids to pass from region to region, largely dependent on gravity. Functionally the colon (ascending colon through the sigmoid part) absorbs water and important ions from the feces. It then compacts the feces for delivery to the rectum. Features of the large intestine include the following (Fig. 4-17):

• Taeniae coli: three longitudinal bands of smooth muscle that are visible on the cecum and colon's surface and assist in peristalsis.

• Haustra: sacculations of the colon created by the contracting taeniae coli.

• Omental appendices: small fat accumulations that are covered by visceral peritoneum and hang from the colon.

• Greater luminal diameter: the large intestine has a larger luminal diameter than the small intestine.

The arterial supply to the cecum, ascending colon, appendix, and most of the transverse colon is provided by branches of the superior mesenteric artery; these portions of the large intestine are derived from the embryonic midgut. The embryonic hindgut gives rise to the distal transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, and anal canal. These are supplied by branches of the inferior mesenteric artery and, in the case of the distal rectum and anal canal, rectal branches from the internal iliac and internal pudendal arteries (see pages 197-200).

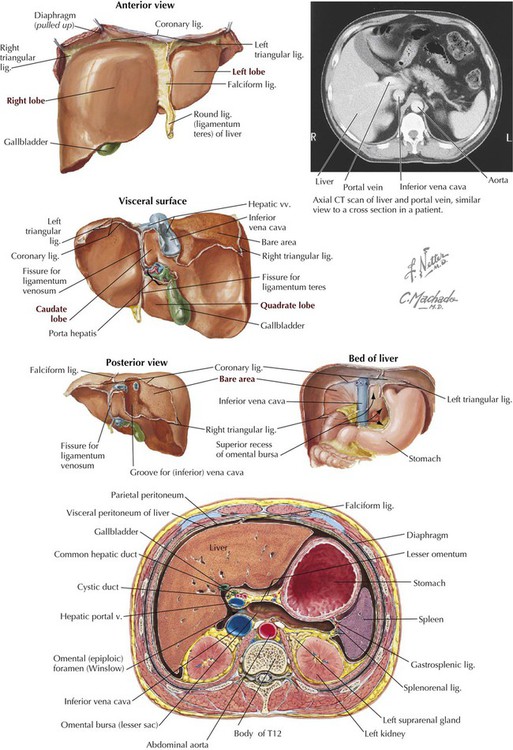

Liver

The liver is the largest solid organ in the body and anatomically is divided into four lobes (Fig. 4-18):

• Quadrate lobe: lies between the gallbladder and round ligament of liver.

• Caudate lobe: lies between the inferior vena cava (IVC), ligamentum venosum, and porta hepatis.

Surgically the liver is divided into right and left halves. The quadrate and caudate anatomical lobes are often considered part of the left half, although some place a portion of the caudate lobe with the right lobe. Surgeons often divide the liver further into eight independent vascular segments based on its vasculature, with each segment receiving a major branch of the hepatic artery, portal vein, hepatic vein (drains the liver's blood into the IVC), and biliary drainage. The external demarcation of the two liver halves runs in an imaginary sagittal plane passing through the gallbladder and IVC (Table 4-9).

TABLE 4-9

Features of the Liver and Its Ligaments

| FEATURE | DESCRIPTION |

| Lobes | Divisions, in functional terms, into right and left lobes, with anatomical subdivisions into quadrate and caudate lobes |

| Round ligament | Ligament that contains obliterated umbilical vein |

| Falciform ligament | Peritoneal reflection off anterior abdominal wall with round ligament in its margin |

| Ligamentum venosum | Ligamentous remnant of fetal ductus venosus, allowing fetal blood from placenta to bypass liver |

| Coronary ligaments | Reflections of peritoneum from liver to diaphragm |

| Bare area | Area of liver pressed against diaphragm that lacks visceral peritoneum |

| Porta hepatis | Site at which vessels, ducts, lymphatics, and nerves enter or leave liver |

The liver is important as it receives the venous drainage from the GI tract, its accessory organs, and the spleen via the portal vein (see Fig. 4-25). The liver serves the following important functions:

• Storage of energy sources (glycogen, fat, protein, and vitamins)

• Production of cellular fuels (glucose, fatty acids, and keto acids)

• Production of plasma proteins and clotting factors

• Metabolism of toxins and drugs

• Modification of many hormones

• Excretion of substances (bilirubin)

• Storage of iron and many vitamins

• Phagocytosis of foreign materials that enter the portal circulation from the bowel

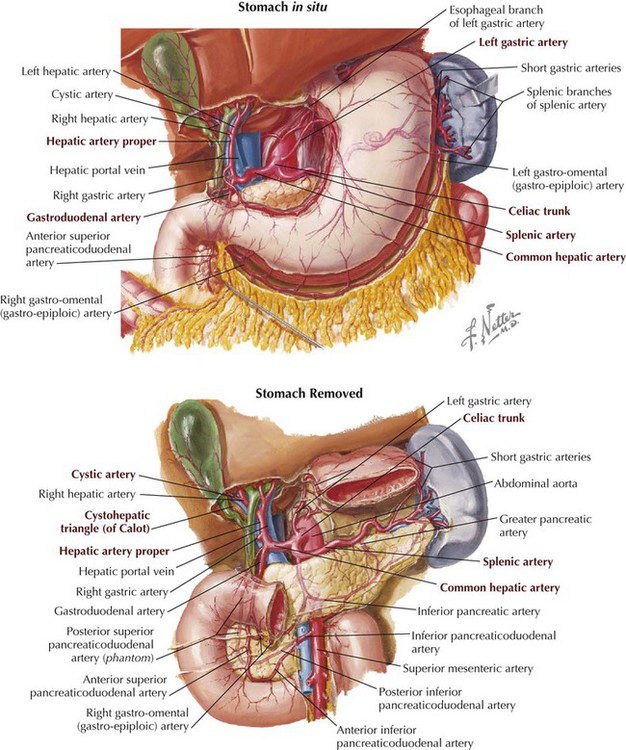

The liver is a derivative of the foregut and receives its arterial supply from branches of the celiac trunk. Its right and left hepatic arteries arise from the hepatic artery proper, a branch of the common hepatic from the celiac trunk. The hepatic artery proper lies in the hepatoduodenal ligament with the common bile duct and portal vein (Figs. 4-18 and 4-19).

Gallbladder

The gallbladder is composed of a fundus, body, and neck. Its function is to receive, store, and concentrate bile. Bile secreted by the hepatocytes of the liver passes through the extrahepatic duct system (Fig. 4-19) as follows:

• Collects in the right and left hepatic ducts after draining the right and left liver lobes.

• Enters the common hepatic duct.

• Enters the cystic duct and is stored and concentrated in the gallbladder.

• On stimulation, largely by vagal efferents and cholecystokinin (CCK), leaves the gallbladder and enters the cystic duct.

• Passes inferiorly down the common bile duct.

• Enters the hepatopancreatic ampulla (of Vater).

• Empties into the second part of the duodenum (major duodenal papilla).

The liver produces about 900 mL of bile per day. Between meals, most of the bile is stored in the gallbladder, which has a capacity of 30 to 50 mL and where the bile is also concentrated. Consequently, bile that reaches the duodenum is a mixture of the more dilute bile directly flowing from the liver and the concentrated bile from the gallbladder.

As a derivative of the embryonic foregut, the gallbladder is supplied by the cystic artery, usually a branch of the right hepatic artery, a branch of the hepatic artery proper (celiac trunk distribution, typical of foregut derivatives). The cystic artery lies in a triangle formed by the liver, cystic duct, and common bile duct, clinically referred to as Calot's triangle (Figs. 4-19 and 4-23). Variations in the biliary system (ducts and vessels) are common, and surgeons must proceed with caution in this area.

Pancreas

The pancreas is an exocrine and endocrine organ that lies posterior to the stomach in the floor of the lesser sac. It is a retroperitoneal organ, except for the distal tail, which is in contact with the spleen (Fig. 4-20). The anatomical parts of the pancreas include the following:

• Head: nestled within the C-shaped curve of the duodenum, with its uncinate process lying posterior to the superior mesenteric vessels.

• Neck: lies anterior to the mesenteric vessels, deep to the pylorus of the stomach.

• Body: extends above the duodenojejunal flexure and across the superior part of the left kidney.

• Tail: terminates at the hilum of the spleen in the splenorenal ligament.

The acinar cells of the exocrine pancreas secrete a number of enzymes necessary for digestion of proteins, starches, and fats. The pancreatic ductal cells secrete fluid with a high bicarbonate content that serves to neutralize the acid entering the duodenum from the stomach. Pancreatic secretion is under neural (vagus nerve) and hormonal (secretin and CCK) control, and the exocrine secretions empty primarily into the main pancreatic duct, which joins the common bile duct at the hepatopancreatic ampulla (of Vater). A smaller accessory pancreatic duct also empties into the second part of the duodenum above the major duodenal papilla (Fig. 4-20).

The endocrine pancreas is represented by clusters of islet cells (of Langerhans), a heterogeneous population of cells responsible for the elaboration and secretion primarily of insulin, glucagon, somatostatin, and several lesser hormones.

The pancreas is a derivative of the embryonic foregut but receives its arterial supply primarily from the celiac trunk (splenic artery and gastroduodenal branch from the common hepatic branch of the celiac artery), but also from branches of the superior mesenteric artery (inferior pancreaticoduodenal branches; see Fig. 4-23).

Spleen

The spleen is slightly larger than a clenched fist and weighs about 180 to 250 grams. It lies in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen and is tucked posterolateral to the stomach under the protection of the lower-left rib cage and diaphragm (Figs. 4-20 and 4-21). Simplistically, the spleen is a large lymph node, becoming larger during infections, although it is also involved in the following very important functions:

• Lymphocyte proliferation (B and T cells)

• Immune surveillance and response

• Destruction of old or damaged red blood cells (RBCs)

• Destruction of damaged platelets

The spleen is tethered between the stomach by the gastrosplenic ligament and the left kidney by the splenorenal ligament. Vessels, nerves, and lymphatics enter or leave the spleen at the hilum (Fig. 4-21). The arterial supply is via the splenic artery from the celiac trunk. Although supplied by the celiac trunk, the spleen is not a foregut embryonic derivative. The spleen is derived from mesoderm, unlike the ductal and epithelial linings of the abdominal GI tract and its accessory organs (liver, gallbladder, pancreas).

Arterial Supply

The arterial supply and the innervation pattern of the abdominal viscera are directly reflected in the embryology of the GI tract, which is discussed later at the end of the chapter. The abdominal GI tract is derived from the following three embryonic gut regions:

• Foregut: gives rise to the abdominal esophagus, stomach, proximal half of the duodenum, liver, gallbladder, and pancreas

• Midgut: distal half of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, cecum, appendix, ascending colon, and proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon

• Hindgut: distal third of the transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, and proximal anal canal

The following three large arteries arise from the anterior aspect of the abdominal aorta; each artery supplies the derivatives of the three embryonic gut regions (Fig. 4-22):

• Celiac trunk (artery): foregut derivatives and the spleen

The celiac trunk arises from the aorta immediately inferior to the diaphragm and divides into the following three main branches (Fig. 4-23):

• Common hepatic artery: supplies the liver, gallbladder, stomach, duodenum, and pancreas (head and neck).

• Left gastric artery: the smallest branch; supplies the stomach and esophagus.

• Splenic artery: the largest branch; takes a tortuous course along the superior margin of the pancreas and supplies the spleen, stomach, and pancreas (neck, body, tail).

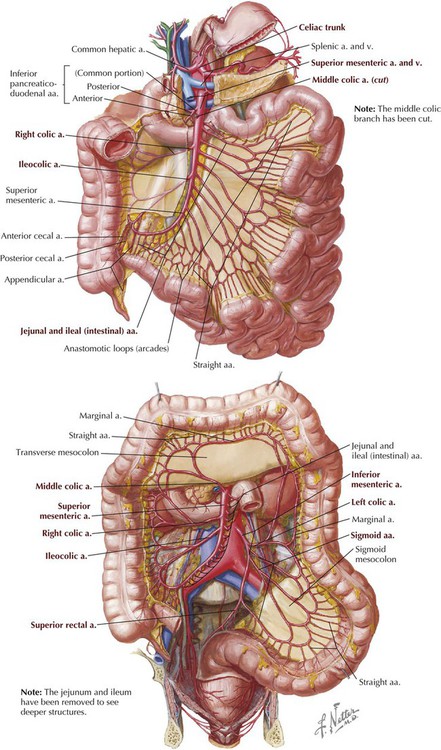

The SMA arises from the aorta about one finger's breadth inferior to the celiac trunk. It then passes posterior to the neck of the pancreas and anterior to the distal duodenum. Its major branches include the following (Fig. 4-24):

• Inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery: supplies the head of the pancreas and duodenum

• Jejunal and ileal branches: give rise to 15 to 18 intestinal branches; they run in the mesentery tethering the jejunum and ileum

• Middle colic artery: runs in the transverse mesocolon; supplies the transverse colon

• Right colic artery: courses retroperitoneally to the right side; supplies the ascending colon; is variable in location

• Ileocolic artery: passes to the right iliac fossa and supplies the ileum, cecum, appendix, and proximal ascending colon; terminal branch of the SMA

The IMA arises from the anterior aorta at about the level of the L3 vertebra (the aorta divides anterior to L4), angles to the left, and gives rise to the following branches (Fig. 4-24):

• Left colic artery: courses to the left and ascends retroperitoneally; supplies the distal transverse colon (by an ascending branch that enters the transverse mesocolon) and the descending colon

• Sigmoid arteries: a variable number of arteries (two to four) that enter the sigmoid mesocolon; supply the sigmoid colon

• Superior rectal artery: a small terminal branch; supplies the distal sigmoid colon and proximal rectum

Along the extent of the abdominal GI tract, the branches of each of these arteries anastomose with each other, providing alternative routes of arterial supply. For example, the marginal artery (of Drummond) (Fig. 4-24) is a large, usually continuous branch that interconnects the right, middle, and left colic branches supplying the large intestine.

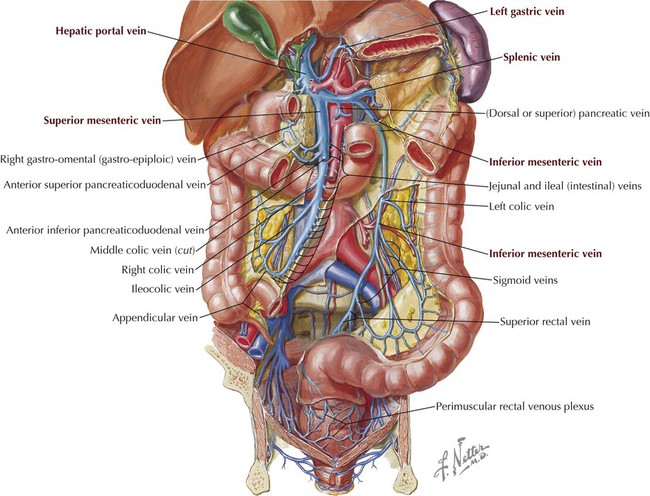

Venous Drainage

The hepatic portal system drains the abdominal GI tract, pancreas, gallbladder, and spleen and ultimately drains into the liver and its sinusoids (Fig. 4-25). By definition, a portal system implies that arterial blood flows into a capillary system (in this case the bowel and its accessory organs), then into larger veins (portal tributaries), and then again into another capillary (or sinusoids) system (liver), before ultimately being collected into larger veins (hepatic veins, IVC) that return the blood to the heart.

The portal vein ascends from behind the pancreas (superior neck) and courses superiorly in the hepatoduodenal ligament (which also contains the common bile duct and hepatic artery proper) to the hilum of the liver; it is formed by the following veins (Figs. 4-25 and 4-26):

• Superior mesenteric vein (SMV): large vein that lies to the right of the SMA and drains portions of the foregut and all of the midgut derivatives.

• Splenic vein: large vein that lies inferior to the splenic artery, parallels its course, and drains the spleen, pancreas, foregut, and, usually, hindgut derivatives (via the inferior mesenteric vein).

The inferior mesenteric vein (IMV), while usually draining into the splenic vein (see Fig. 4-25), also may drain into the junction of the SMV and splenic vein or drain directly into the SMV.

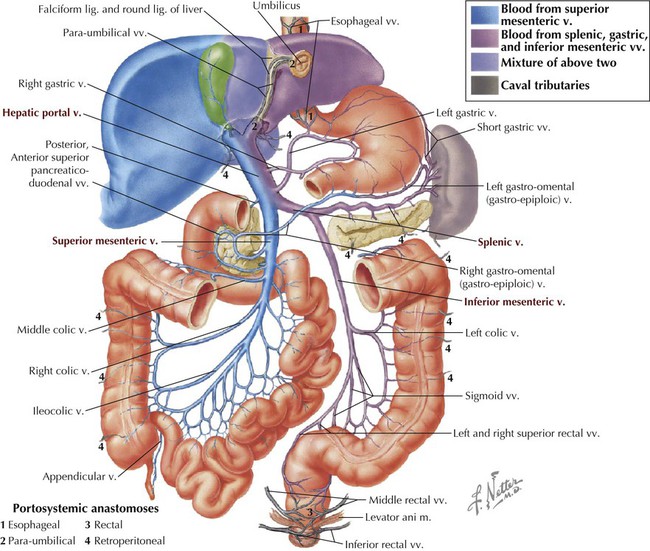

Typical of most veins in the body, the portal system has numerous anastomoses with other veins, specifically in this case with the tributaries of the caval system (IVC and azygos system of veins; Fig. 4-26). These anastomoses allow for the rerouting of venous return to the heart (these veins do not possess valves) should a major vein become occluded. The most important portosystemic anastomoses are around the lower esophagus (veins can enlarge and form varices), around the rectum and anal canal (present as hemorrhoids), and in the para-umbilical region (present as a caput medusae).

Lymphatics

Lymphatic drainage from the stomach, portions of the duodenum, liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and spleen is largely from regional nodes associated with those organs to a central collection of lymph nodes around the celiac trunk (Fig. 4-27). Lymphatic drainage from the midgut derivatives is largely to superior mesenteric nodes adjacent to the superior mesenteric artery, and hindgut derivatives (from the distal transverse colon to the distal rectum) drain to inferior mesenteric nodes adjacent to the artery of the same name (Fig. 4-28). These nodal collections often are referred to as the pre-aortic and para-aortic nodes and ultimately drain to the cisterna chyli (dilated proximal end of the thoracic duct), which is located adjacent to the celiac trunk.

Innervation

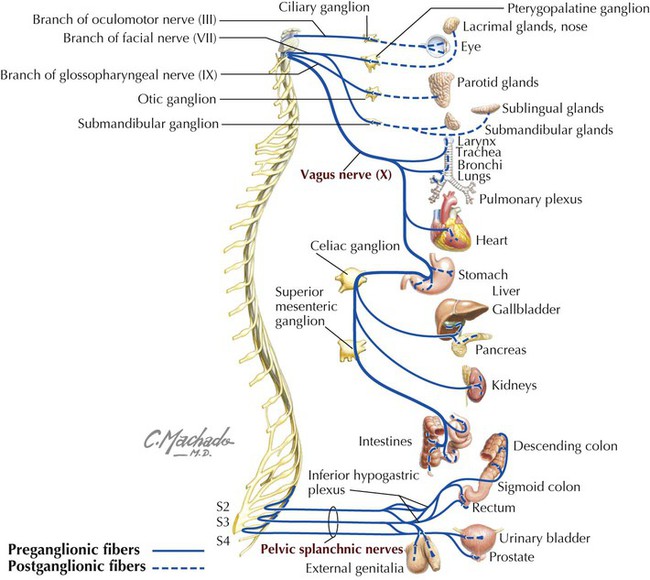

The abdominal viscera are innervated by the autonomic nervous system (ANS), and the pattern of innervation closely parallels the arterial supply to the various embryonic gut regions (see Table 4-14). Additionally, the enteric nervous system provides an “intrinsic” network of ganglia with connections to the ANS, which helps coordinate peristalsis and secretion (see Chapter 1). The enteric ganglia and nerve plexuses include the myenteric plexus and submucosal plexus within the layers of the bowel wall.

The sympathetic innervation of the viscera is derived from the following nerves (Figs. 4-29 and 4-30):

• Thoracic splanchnic nerves: greater (T5-T9), lesser (T10-T11), and least (T12) splanchnic nerves (the nerve branches from the thoracic ganglia from which these splanchnic nerves arise often is variable) that convey preganglionic axons to the prevertebral ganglia to innervate the foregut and midgut derivatives.

• Lumbar splanchnic nerves: usually several lumbar splanchnic nerves (L1-L2 or L3) that convey preganglionic axons to the prevertebral ganglia and plexus to innervate the hindgut derivatives.

Postganglionic sympathetic axons arise from the postganglionic neurons in the prevertebral ganglia (celiac, superior mesenteric, and inferior mesenteric ganglia) and plexus and travel with the blood vessels to their target viscera. Generally, sympathetic stimulation leads to the following:

The parasympathetic innervation of the viscera is derived from the following nerves (see Table 4-14 and Figs. 4-29 and 4-30):

• Vagus nerves: anterior and posterior vagal trunks enter the abdomen on the esophagus and send preganglionic axons directly to postganglionic neurons in the walls of the viscera derived from the foregut and midgut (distal esophagus to the proximal two thirds of the transverse colon).

• Pelvic splanchnic nerves: preganglionic axons from S2-S4 travel via these splanchnic nerves to the prevertebral plexus (inferior hypogastric plexus) and distribute to the postganglionic neurons of the hindgut derivatives. (Note: pelvic splanchnic nerves are not part of the sympathetic trunk; only sympathetic neurons and axons reside in the sympathetic trunk and chain ganglia.)

Many postganglionic parasympathetic neurons are in the myenteric and submucosal ganglia and plexuses that compose the enteric nervous system (see Chapter 1). Generally, parasympathetic stimulation leads to the following:

Visceral afferent fibers travel with the ANS components and can be summarized as follows:

• Pain afferents: include the pain of distention, inflammation, and ischemia, which is conveyed to the central nervous system (CNS) largely by the sympathetic components to the spinal dorsal root ganglia associated with the T5-L2 spinal cord levels.

• Reflex afferents: include information from chemoreceptors, osmoreceptors, and mechanoreceptors, which are conveyed to autonomic centers in the medulla oblongata via the vagus nerves.

Gastrointestinal function is a coordinated effort not only by the “hard-wired” components of the ANS and enteric nervous system, as described earlier, but also by the immune and endocrine systems. In fact, many view the GI tract as the largest endocrine organ in the body, secreting and responding to dozens of GI hormones and other neuroimmune substances.

6 Posterior Abdominal Wall and Viscera

Posterior Abdominal Wall

The posterior abdominal wall and its visceral structures lie deep to the parietal peritoneum (retroperitoneal) lining the posterior abdominal cavity. This region contains skeletal structures, muscles, major vascular channels, adrenal glands, the upper urinary system, nerves, and lymphatics.

Fascia and Muscles

Deep to the parietal peritoneum, the muscles of the posterior abdominal wall are enveloped in a layer of investing fascia called the endoabdominal fascia, which is continuous laterally with the transversalis fascia of the transversus abdominis muscle. For identification, the fascia is named according to the structures it covers and includes the following layers (Figs. 4-31 and 4-32):

• Psoas fascia: covers the psoas major muscle and is thickened superiorly, forming the medial arcuate ligament.

• Thoracolumbar fascia: anterior layer covers the quadratus lumborum muscle and is thickened superiorly, forming the lateral arcuate ligament; middle and posterior layers envelop the erector spinae muscles of the back.

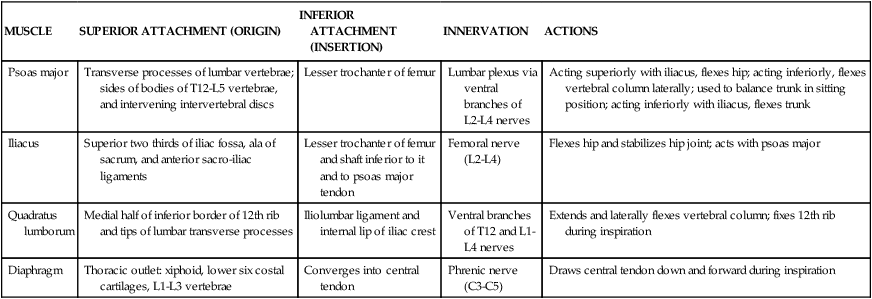

The muscles of the posterior abdominal wall have attachments to the lower rib cage, the T12-L5 vertebrae, and bones of the pelvic girdle (Table 4-10 and Fig. 4-32). Note that the diaphragm has a central tendinous portion and is attached to the lumbar vertebrae by a right crus and a left crus (leg), which are joined centrally by the median arcuate ligament that passes over the emerging abdominal aorta. The inferior vena cava passes through the diaphragm at the T8 vertebral level to enter the right atrium of the heart. The right phrenic nerve may accompany the IVC as it passes through the diaphragm, which it innervates. The esophagus passes through the diaphragm at the T10 vertebral level, along with the anterior and posterior vagal trunks and left gastric vessels. The aorta passes through the diaphragm at the T12 vertebral level and is accompanied by the thoracic duct and often the azygos vein as they course superiorly.

TABLE 4-10

Muscles of Posterior Abdominal Wall

| MUSCLE | SUPERIOR ATTACHMENT (ORIGIN) | INFERIOR ATTACHMENT (INSERTION) | INNERVATION | ACTIONS |

| Psoas major | Transverse processes of lumbar vertebrae; sides of bodies of T12-L5 vertebrae, and intervening intervertebral discs | Lesser trochanter of femur | Lumbar plexus via ventral branches of L2-L4 nerves | Acting superiorly with iliacus, flexes hip; acting inferiorly, flexes vertebral column laterally; used to balance trunk in sitting position; acting inferiorly with iliacus, flexes trunk |

| Iliacus | Superior two thirds of iliac fossa, ala of sacrum, and anterior sacro-iliac ligaments | Lesser trochanter of femur and shaft inferior to it and to psoas major tendon | Femoral nerve (L2-L4) | Flexes hip and stabilizes hip joint; acts with psoas major |

| Quadratus lumborum | Medial half of inferior border of 12th rib and tips of lumbar transverse processes | Iliolumbar ligament and internal lip of iliac crest | Ventral branches of T12 and L1-L4 nerves | Extends and laterally flexes vertebral column; fixes 12th rib during inspiration |

| Diaphragm | Thoracic outlet: xiphoid, lower six costal cartilages, L1-L3 vertebrae | Converges into central tendon | Phrenic nerve (C3-C5) | Draws central tendon down and forward during inspiration |

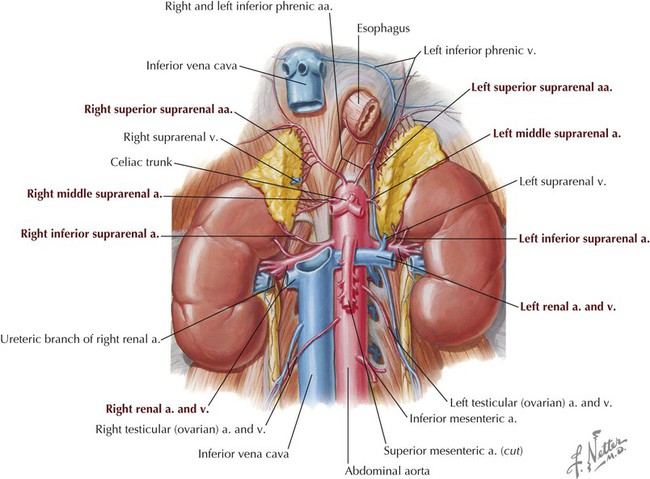

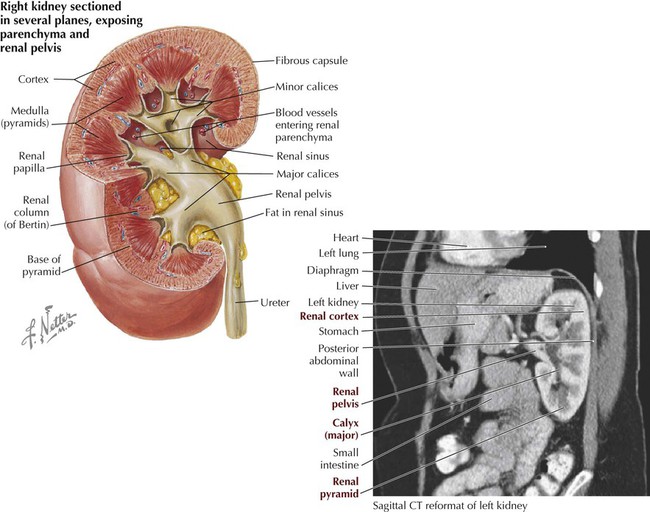

Kidneys and Adrenal (Suprarenal) Glands

The kidneys and adrenal glands are retroperitoneal organs that receive a rich arterial supply (Fig. 4-33). The right kidney usually lies somewhat lower than the left kidney because of the presence of the liver.

Each kidney is enclosed in the following layers of fascia and fat (Figs. 4-31 and 4-34):

• Renal capsule: covers each kidney; a thick fibroconnective tissue capsule.

• Perirenal (perinephric) fat: directly surrounds the kidney (and adrenal glands) and cushions it.

• Renal fascia: surrounds the kidney (and adrenal glands) and perirenal fat; superiorly it is continuous with the fascia covering the diaphragm; inferiorly it may blend with the transversalis fascia; medially the anterior layer blends with the vessels in the renal hilum and the connective tissue of the aorta and IVC.

• Pararenal (paranephric) fat: an outer layer of fat that is variable in thickness and is continuous with the extraperitoneal (retroperitoneal) fat.

The kidneys are related posteriorly to the diaphragm and muscles of the posterior abdominal wall, as well as the 11th and 12th (floating) ribs. They move with respiration, and anteriorly are in relation to the abdominal viscera and mesenteries shown in Figure 4-14. For the right kidney, this includes the liver, second part of the duodenum, and ascending colon. For the left kidney, this includes the stomach, pancreas, spleen, and descending colon. Each kidney also is “capped” by the adrenal (suprarenal) glands. Variability in these relationships is common because of the size of the kidneys and adjacent viscera, disposition of mobile portions of the bowel, and extent of the mesenteries.

Structurally, each kidney has the following gross features (Fig. 4-35):

• Renal capsule: a fibroconnective tissue capsule that surrounds the renal cortex.

• Renal cortex: outer layer that surrounds the renal medulla and contains nephrons (units of filtration) and renal tubules.

• Renal medulla: inner layer (usually appears darker) that contains renal tubules and collecting ducts that convey the filtrate to minor calices; the renal cortex extends as renal columns between the medulla, demarcating the distinctive renal pyramids whose apex (renal papilla) terminates with a minor calyx.

• Minor calyx: structure that receives urine from the collecting ducts of the renal pyramids.

• Major calyx: site at which several minor calices drain.

• Renal pelvis: point at which several major calices unite; conveys urine to the proximal ureter.

• Hilum: medial aspect of each kidney, where the renal pelvis emerges from the kidney and where vessels, nerves, and lymphatics enter or leave the kidney.

The ureters are about 25 cm (10 inches) long, extend from the renal pelvis to the urinary bladder, are composed of a thick layer of smooth muscle, and lie in a retroperitoneal position.

The right adrenal (suprarenal) gland often is pyramidal in shape, whereas the left gland is semilunar (see Fig. 4-33). Each adrenal gland “caps” the superior pole of the kidney and is surrounded by perirenal fat and renal fascia. The right adrenal gland is close to the IVC and liver, whereas the stomach, pancreas, and even the spleen can lie anterior to the left adrenal gland.

As endocrine organs, the adrenal glands have a rich vascular supply from superior suprarenal arteries (branches of the inferior phrenic arteries), middle suprarenal arteries directly from the aorta, and inferior suprarenal arteries from the renal arteries (see Fig. 4-36). The kidneys and adrenal glands are innervated by the ANS. Sympathetic nerves arise from the T12-L2 spinal levels and synapse in the superior mesenteric ganglia and superior hypogastric plexuses and send postganglionic fibers to the kidney. Preganglionic fibers from lower thoracic levels travel directly to the adrenal medulla and synapse on the cells of the adrenal medulla (neuroendocrine cells that are the postganglionic part of the sympathetic system). Parasympathetic nerves to the kidneys and adrenal gland travel with the vagus nerves and synapse on postganglionic neurons within the kidney and adrenal cortex (see Figs. 4-29 and 4-30).

Abdominal Vessels

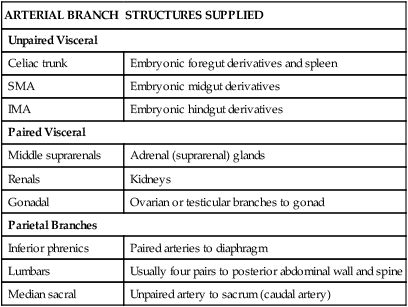

The abdominal aorta extends from the aortic hiatus (T12) to the lower level of L4, where it divides into the right and left common iliac arteries (Fig. 4-36). The abdominal aorta gives rise to the following three groups of arteries (Table 4-11):

TABLE 4-11

| ARTERIAL BRANCH | STRUCTURES SUPPLIED |

| Unpaired Visceral | |

| Celiac trunk | Embryonic foregut derivatives and spleen |

| SMA | Embryonic midgut derivatives |

| IMA | Embryonic hindgut derivatives |

| Paired Visceral | |

| Middle suprarenals | Adrenal (suprarenal) glands |

| Renals | Kidneys |

| Gonadal | Ovarian or testicular branches to gonad |

| Parietal Branches | |

| Inferior phrenics | Paired arteries to diaphragm |

| Lumbars | Usually four pairs to posterior abdominal wall and spine |

| Median sacral | Unpaired artery to sacrum (caudal artery) |

SMA, Superior mesenteric artery; IMA, inferior mesenteric artery.

• Unpaired visceral arteries to the GI tract, spleen, pancreas, gallbladder, and liver

• Paired visceral arteries to the kidneys, adrenal glands, and gonads

The inferior vena cava drains abdominal structures other than the GI tract and the spleen, which are drained by the hepatic portal system (Fig. 4-37). The IVC begins by the union of the two common iliac veins just to the right and slightly inferior of the midline distal abdominal aorta and ascends to pierce the diaphragm at the level of the T8 vertebral level, where it empties into the right atrium. Most of the IVC tributaries parallel the arterial branches of the aorta, but two or three hepatic veins also enter the IVC just inferior to the diaphragm. It is important to note that the ascending lumbar veins connect adjacent lumbar veins and drain superiorly into the azygos venous system (see Chapter 3). This venous anastomosis is important if the IVC should become obstructed.

Arteries of the Abdominal Aorta

The abdominal aorta (1) is a continuation of the thoracic aorta beginning at about the level of the T12 vertebra, where the aorta passes through the aortic hiatus of the diaphragm. It gives off three sets of parietal arteries that supply the diaphragm (inferior phrenic artery [2]), usually four pairs of lumbar arteries (3), and an unpaired medial sacral artery (4), our equivalent of the “caudal artery” (for the tail) in most other mammals. These arteries arise from the posterolateral aspect of the aorta (Fig. 4-38).

The abdominal aorta (1) also gives rise to three unpaired visceral arteries that arise from the anterior aspect of the aorta. The celiac trunk (5) supplies the embryonic foregut derivatives of the gastrointestinal tract and its accessory organs, the gallbladder, liver, and pancreas. It also supplies the spleen, an organ of the immune system. The superior mesenteric artery (6) supplies the embryonic midgut derivatives (distal duodenum, small intestine, cecum, appendix, ascending colon, and proximal two thirds of the transverse colon) and also portions of the pancreas. The inferior mesenteric artery (7) supplies the embryonic hindgut derivatives (distal transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, and proximal rectum).

The abdominal aorta (1) finally gives rise to three paired visceral arteries that supply the suprarenal (adrenal) glands via the paired middle suprarenal artery (8), the kidneys via the paired renal artery (9), and the gonads via the paired ovarian/testicular artery (10). The paired visceral branches arise from the lateral aspect of the abdominal aorta (1). The aorta then divides into the right and left common iliac arteries.

A rich blood supply is common around the stomach, duodenum, and pancreas. The suprarenal glands also receive a rich vascular supply (superior, middle, and inferior suprarenal arteries). The small bowel has a collateral circulation via its arcades and the colon via its marginal artery, although the pattern and supply by these arteries is variable.

In the outline of the arteries (Fig. 4-38), major vessels often dissected in anatomy courses include the first-order arteries (in bold and numbered) and their second-order major branches. In more detailed dissection courses some or all of the third- and/or fourth-order arteries may also be dissected.

Veins of the Abdomen (Caval System)

As elsewhere in the body, the veins of the abdomen possess a deep and superficial group. The deep veins drain essentially the areas supplied by the “parietal and paired visceral” branches of the abdominal aorta (Fig. 4-39). (Note that the “unpaired visceral” branches of the abdominal aorta supplying the GI tract, its accessory organs, and the spleen are drained by the hepatic portal system of veins.)

Beginning at the level of the pelvic brim, the common iliac vein (1) is formed by the internal and external iliac veins. The two common iliac veins (1) join to form the inferior vena cava (2), which receives venous drainage from the gonads, kidneys, posterior abdominal wall (lumbar veins), liver, and diaphragm. The IVC then drains into the right atrium of the heart (3).

The superficial set of veins drain the anterolateral abdominal wall, the superficial inguinal region, rectus sheath, and lateral thoracic wall. Most of its connections ultimately drain into the axillary vein (4) and then into the subclavian vein, brachiocephalic veins, which form the superior vena cava, and then into the heart (3). The inferior epigastric veins (from the external iliac veins) enter the posterior rectus sheath and course cranially above the umbilicus as the superior epigastric veins and then anastomose with the internal thoracic veins that drain into the subclavian veins (see Fig. 4-3).

The superficial veins can become enlarged during portal hypertension, when the venous flow through the liver is compromised. Important portosystemic anastomoses between the portal system and caval system can allow venous blood to gain access to the caval veins (both deep and superficial veins) to assist in returning blood to the heart.

Variations in the venous pattern and in the number of veins and their size are common, so it is best to understand the major venous channels and realize that smaller veins often are more variable.

Hepatic Portal System of Veins

The hepatic portal system of veins drains the abdominal GI tract and two of its accessory organs (pancreas and gallbladder) and the spleen (immune system organ) (Fig. 4-40). This blood then collects largely in the liver, where processing of absorbed GI contents takes place. (However, most fats are absorbed by the lymphatics and returned via the thoracic duct to the venous system in the neck, at the junction of the left internal jugular and left subclavian veins.) Venous blood is returned to the liver and then collects in the right, intermediate, and left hepatic veins (5) and is drained into the inferior vena cava (6) and then the right atrium of the heart (7).

The inferior mesenteric vein (1) essentially drains the area supplied by the inferior mesenteric artery (embryonic hindgut derivatives) and then drains into the splenic vein (2). (Sometimes it also drains into the junction between the splenic and superior mesenteric vein [SMV] or into the SMV directly.) The splenic vein (2) drains the spleen and portions of the stomach and pancreas. The superior mesenteric vein (3) essentially drains the same region supplied by the superior mesenteric artery (embryonic midgut derivatives), as well as portions of the pancreas and stomach.

The splenic vein (2) and superior mesenteric vein (3) unite to form the portal vein (4). The portal vein (4) is about 8-10 cm long and receives not only venous blood from the splenic vein (2) and SMV (3) but also smaller tributaries that drain from the stomach, para-umbilical region, and cystic duct (of the gallbladder). Just before entering the liver, the portal vein (4) divides into its right and left branches, one to each of the two physiologically functional lobes of the liver. Blood leaving the liver collects into hepatic veins (5) and drains into the IVC (6) and then the heart (7).

If blood cannot traverse the hepatic sinusoids (liver disease), it backs up in the portal system and causes portal hypertension. The large amount of venous blood in the portal system then must find its way back to the heart and does so by important portosystemic anastomotic connections that utilize the inferior and superior venae cavae as alternate routes to the heart. Important portosystemic anastomoses occur in the following regions:

• Esophageal veins from the portal vein that connect with the azygos system of veins draining into the SVC

• Rectal veins (superior rectal vein of portal system to middle and inferior rectal veins) that ultimately drain into the IVC

• Para-umbilical veins of the superficial abdominal wall that can drain into the tributaries of either the SVC or the IVC

• Retroperitoneal venous connections wherever the bowel is up against the abdominal wall and is drained by small parietal venous tributaries

As with all veins, these veins can be variable in number and size, but the major venous channels are relatively constant anatomically.

Lymphatic Drainage

Lymph from the posterior abdominal wall and retroperitoneal viscera drains medially, following the arterial supply back to lumbar and visceral preaortic lymph nodes (Fig. 4-41). Ultimately, the lymph is collected into the cisterna chyli and conveyed to the venous system by the thoracic duct.

Innervation

Retroperitoneal visceral structures of the posterior abdominal wall (adrenal glands, kidneys, ureters) are supplied by parasympathetic fibers from the vagus nerve and by the pelvic splanchnics (S2-S4) to the distal ureters (pelvic ureters) (see Fig. 4-30). Sympathetic nerves (secretomotor) to the adrenal medulla come from the lesser and least splanchnic nerves, and sympathetic nerves to the kidneys and proximal ureters come from the lesser and least splanchnic nerves (T10-T12) and the lumbar splanchnics (L1-L2) (see Fig. 4-29). They synapse in the superior hypogastric plexus and superior mesenteric ganglion and send postganglionic sympathetics to the kidneys on the vasculature.

Pain afferents from all the abdominal viscera pass to the spinal cord largely by following the thoracic and lumbar splanchnic sympathetic nerves (T5-L2). The neuronal cell bodies of these afferent fibers reside in the respective dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord segment. Thus, visceral pain may be perceived as somatic pain over these dermatome regions, a phenomenon known clinically as referred pain. Pain afferents from pelvic viscera largely follow pelvic splanchnic parasympathetic nerves (S2-S4) into the cord, and the pain is largely confined to the pelvic region. Common sites of referred visceral pain are shown in Figure 4-42 and summarized in Table 4-12.

TABLE 4-12

Spinal Cord Levels for Visceral Referred Pain*

| ORGAN | SPINAL CORD LEVEL | ANTERIOR ABDOMINAL REGION OR QUADRANT |

| Stomach | T5-T9 | Epigastric or left hypochondrium |

| Spleen | T6-T8 | Left hypochondrium |

| Duodenum | T5-T8 | Epigastric or right hypochondrium |

| Pancreas | T7-T9 | Inferior part of epigastric |

| Liver or gallbladder† | T6-T9 | Epigastric or right hypochondrium |

| Jejunum | T6-T10 | Umbilical |

| Ileum | T7-T10 | Umbilical |

| Cecum | T10-T11 | Umbilical or right lumbar or right lower quadrant |

| Appendix | T10-T11 | Umbilical or right inguinal or right lower quadrant |

| Ascending colon | T10-T12 | Umbilical or right lumbar |

| Sigmoid colon | L1-L2 | Left lumbar or left lower quadrant |

| Kidney | T10-L1 | Lower hypochondrium or lumbar |

| Ureter | T11-L1 | Lumbar to inguinal (loin to groin) |

*These spinal cord levels are approximate. Although normal variations are common from individual to individual, these levels do show the approximate contributions.

†Irritation of the diaphragm leads to pain referred to the back (inferior scapula) and shoulder region.

Somatic nerves of the posterior abdominal wall are derived from the lumbar plexus, which is composed of the ventral rami of L1-L4 (often with a small contribution from T12) (Fig. 4-43). The branches of the lumbar plexus are summarized in Table 4-13.

TABLE 4-13

| NERVE | FUNCTION AND INNERVATION |

| Subcostal (T12) | Last thoracic nerve; courses inferior to 12th rib |

| Iliohypogastric (L1) | Motor and sensory; above pubis and posterolateral buttocks |

| Ilio-inguinal (L1) | Motor and sensory; sensory to inguinal region |

| Genitofemoral (L1-L2) | Genital branch to cremaster muscle; femoral branch to femoral triangle |

| Lateral cutaneous nerve of thigh (L2-L3) | Sensory to anterolateral thigh |

| Femoral (L2-L4) | Motor in pelvis (to iliacus) and anterior thigh muscles; sensory to thigh and medial leg |

| Obturator (L2-L4) | Motor to adductor muscles in thigh; sensory to medial thigh |

| Accessory obturator | Inconstant (10%); motor to pectineus muscle |

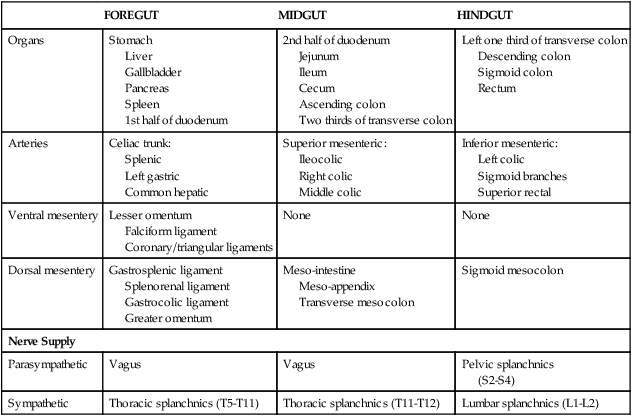

7 Embryology

Summary of Gut Development

The embryonic gut begins as a midline endoderm-lined tube that is divided into foregut, midgut, and hindgut regions, each giving rise to adult visceral structures with a segmental vascular supply and autonomic innervation (Fig. 4-44 and Table 4-14). Knowing this pattern of distribution related to the three embryonic gut regions will help you better organize your thinking about the abdominal viscera and their neurovascular supply.

TABLE 4-14

Summary of Embryonic Gut Development

| FOREGUT | MIDGUT | HINDGUT | |

| Organs | Stomach Liver Gallbladder Pancreas Spleen 1st half of duodenum |

2nd half of duodenum Jejunum Ileum Cecum Ascending colon Two thirds of transverse colon |

Left one third of transverse colon Descending colon Sigmoid colon Rectum |

| Arteries | Celiac trunk: Splenic Left gastric Common hepatic |

Superior mesenteric: Ileocolic Right colic Middle colic |

Inferior mesenteric: Left colic Sigmoid branches Superior rectal |

| Ventral mesentery | Lesser omentum Falciform ligament Coronary/triangular ligaments |

None | None |

| Dorsal mesentery | Gastrosplenic ligament Splenorenal ligament Gastrocolic ligament Greater omentum |

Meso-intestine Meso-appendix Transverse mesocolon |

Sigmoid mesocolon |

| Nerve Supply | |||

| Parasympathetic | Vagus | Vagus | Pelvic splanchnics (S2-S4) |

| Sympathetic | Thoracic splanchnics (T5-T11) | Thoracic splanchnics (T11-T12) | Lumbar splanchnics (L1-L2) |

The gut undergoes a series of rotations and differential growth that ultimately contributes to the postnatal disposition of the abdominal GI tract (see Fig. 4-44). This sequence of events can be summarized as follows:

• The stomach rotates 90 degrees clockwise on its longitudinal axis so that the left side of the gut tube now faces anteriorly.

• As the stomach rotates, the duodenum swings to the right into its familiar C-shaped configuration and becomes largely retroperitoneal.

• The midgut forms an initial primary intestinal loop by rotating 180 degrees counterclockwise around the axis of the SMA (which supplies blood to the midgut) and, because of its fast growth, herniates out into the umbilical cord (6 weeks).

• By the 10th week, the gut loop returns into the abdominal cavity and completes its rotation with a 90-degree swing to the right lower quadrant.

• Thus, the midgut loop completes a 270-degree rotation about the axis of the SMA and undergoes significant differential growth to form the small intestine and proximal portions of the large intestine (see Table 4-14).

• The hindgut then develops into the remainder of the large intestine and proximal rectum, supplied by the IMA, and ending in the cloaca (Latin for “sewer”).

Liver, Gallbladder, and Pancreas Development

During the third week of development, an endodermal outpocketing of the foregut gives rise to the hepatic diverticulum (Fig. 4-45). Further development of this diverticulum gives rise to the liver, the biliary duct system, and the gallbladder. The liver cells (hepatocytes) are endodermal derivatives. A short time later, two pancreatic buds (ventral and dorsal) originate as endodermal outgrowths of the duodenum. As the duodenum swings to the right during rotation of the stomach, the ventral pancreatic bud (which will form part of the pancreatic head and the uncinate process) swings around posteriorly and fuses with the dorsal bud to form the union of the two pancreatic ducts (main and accessory ducts) and buds. This fused pancreas embraces the SMV and SMA, which are in relationship to these developing embryonic buds (see Figs. 4-20 and 4-45). The endoderm of the pancreas gives rise to the exocrine and endocrine cells of the organ, whereas the connective tissue stroma is formed by mesoderm.

Urinary System Development

Initially, retroperitoneal intermediate mesoderm differentiates into the nephrogenic (kidney) tissue and forms the following (Fig. 4-46):

• Pronephros, which degenerates

• Mesonephros with its mesonephric duct, which functions briefly before degenerating

• Metanephros, the definitive kidney tissue (nephrons and loop of Henle) into which the ureteric bud (an outgrowth of the mesonephric duct) grows and differentiates into the ureter, renal pelvis, calices, and collecting ducts

By differential growth and some migration, the kidney “ascends” from the sacral region, first with its hilum directed anteriorly and then medially, until it reaches its adult location (Fig. 4-47). Around the 12th week, the kidney becomes functional as the fetus swallows amniotic fluid, urinates into the amniotic cavity, and continually recycles fluid in this manner. Toxic fetal wastes, however, are removed through the placenta into the maternal circulation.

Adrenal (Suprarenal) Gland Development

The adrenal cortex develops from mesoderm, whereas the adrenal medulla forms from neural crest cells, which migrate into the cortex and aggregate in the center of the gland. The cells of the medulla are essentially the postganglionic neurons of the sympathetic division of the ANS, but secrete mainly epinephrine and some norepinephrine into the blood as neuroendocrine cells.