Uncommon, Atypical, and Often Unrecognized PSG Patterns

In the day-to-day interpretation of polysomnograms (PSGs), the polysomnographer often encounters patterns that are atypical and unrecognized because they do not conform to what is commonly seen. However, these patterns may have clinical significance, and therefore it is important to recognize them to design future studies that may elucidate their pathophysiological characteristics and relevance. In almost every PSG tracing focusing on multiple physiological characteristics, there is always something not described previously, because of individual variation in the physiological processes of various body systems. Furthermore, we do not yet understand all the complex changes in the cardiovascular, respiratory, endocrine, and motor systems during sleep, and these may express themselves in unusual manners.

The following snapshots from overnight PSG tracings highlight some of these uncommon, atypical, and often unrecognized patterns (Figs. 9.1 to 9.19).

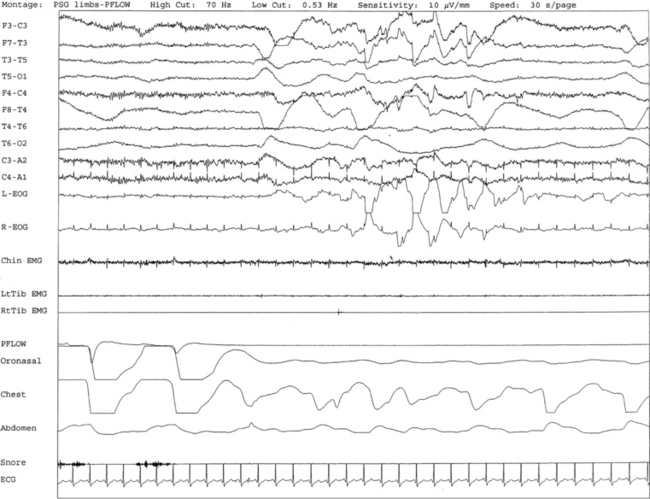

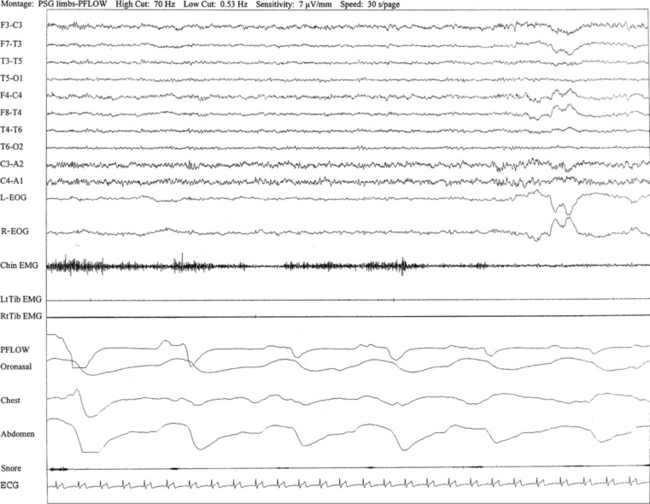

FIGURE 9.1 A case of sweating in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

Overnight polysomnogram (PSG) shows evidence of severe upper airway obstructive sleep apnea with an apnea-hypopnea index of 51.3/hr in a 71-year-old man with history of snoring, difficulty breathing in sleep, and excessive daytime sleepiness despite uvulopalatoplasty performed 2 years ago for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Medical history is significant for hypertension. In addition, the PSG shows the presence of sweating recurrently and exclusively during REM sleep while being conspicuously absent during non-REM sleep. This is an atypical finding, raising the suggestion of REM sleep dysregulation. This figure shows a 30-second excerpt in REM sleep taken from overnight PSG recording showing sweat artifact as described for Figure 1.7. Top 10 channels, Electroencephalography; L-EOG and R-EOG, left and right electro-oculograms; electromyography of chin; LtTib and RtTib EMG, left and right tibialis anterior electromyography; PFLOW, nasal pressure transducer; oronasal thermistor; chest and abdomen effort channels; snore monitor; ECG, electrocardiography.

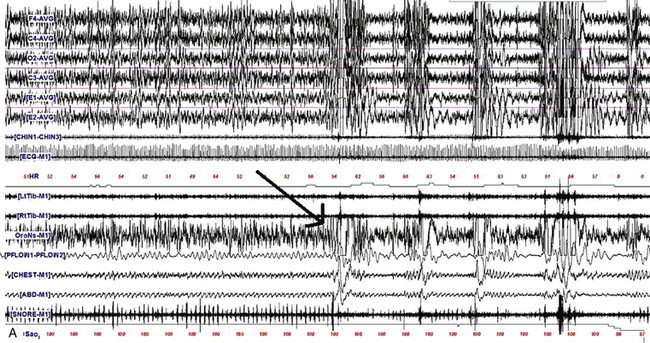

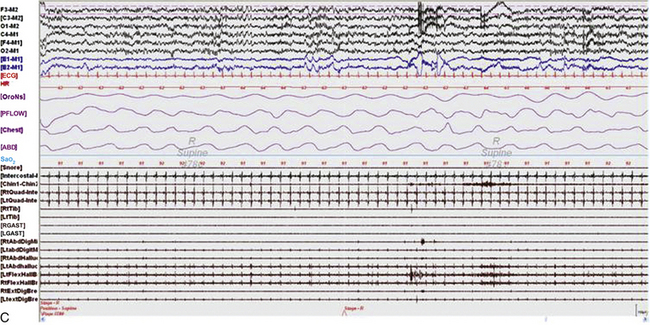

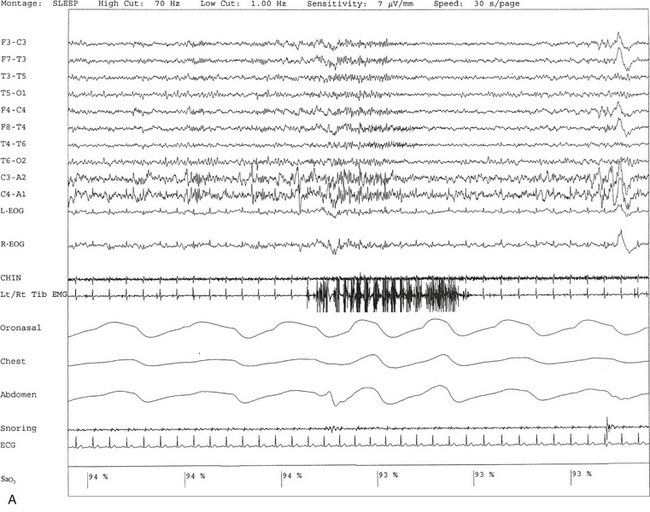

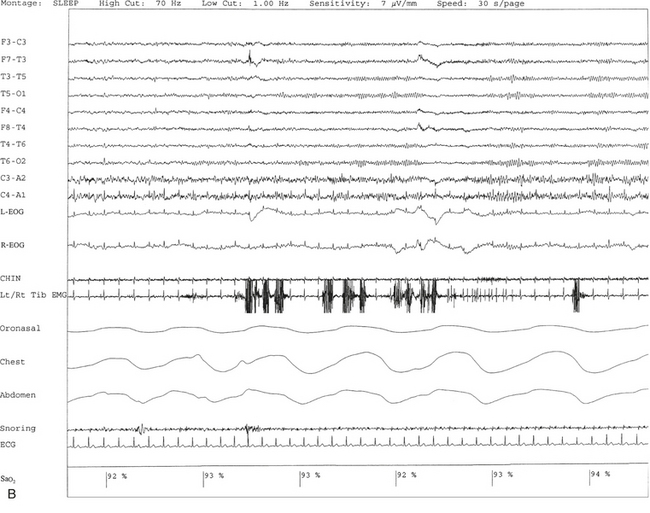

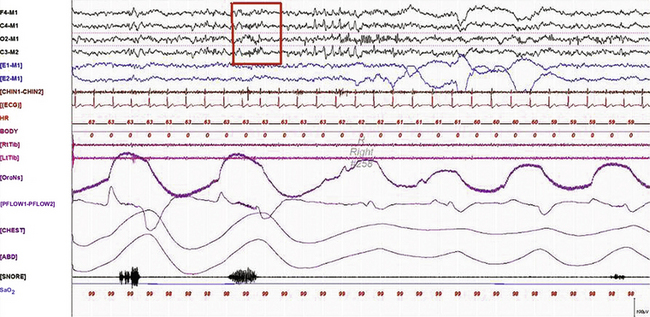

FIGURE 9.2 The effect of lateral head position on sleep-disordered breathing (SDB).

A, A 480-second epoch of polysomnographic tracing from stage N2 sleep in a 63-year-old man showing supine body position with head initially turned to the left and then to the right (arrow marks point of head position change). Note the immediate appearance of respiratory events with the head turned to the right. B, A 480-second excerpt from stage N2 sleep in a 6-year-old boy showing supine body position with head initially supine and then turned to the left (first arrow marks the point of this change). Respiratory events improved after 2 to 3 minutes in the same position (second arrow). Although worsening of obstructive sleep apnea with the supine body position is well known, recent reports have also confirmed that sleep-disordered breathing worsens with the head supine. However, worsening of sleep-disordered breathing with the head turned laterally to one side or the other and the body remaining supine as illustrated in this example is unusual. Top four channels in A and eight channels in B, Electroencephalography (international 10-20 electrode nomenclature); E1-M1 and E2-M1, left and right electro-oculogram; CHIN1-CHIN2, chin electromyography; ECG, electrocardiogram; HR, heart rate; LtTib and RtTib, left and right tibialis anterior electromyogram (EMG); LGAST and RGAST, left and right gastrocnemius EMG; OroNs and PFLOW, respiratory air flow; Chest and ABD, respiratory effort; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation by finger oximetry; snore channel. (Reproduced with permission from Riar S, Bhat S, Kabak B, Gupta D, Smith I, Chokroverty S. The effect of lateral head position on sleep disordered breathing: a case series. Sleep Med. 2013;14[2]:220-221.)

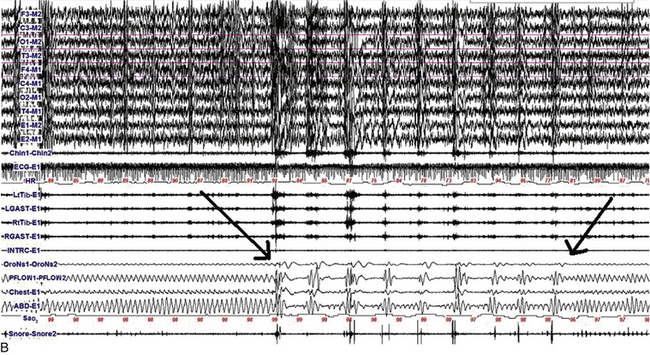

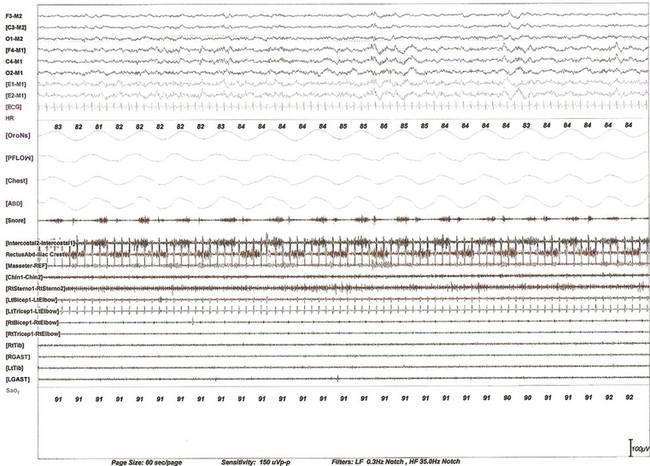

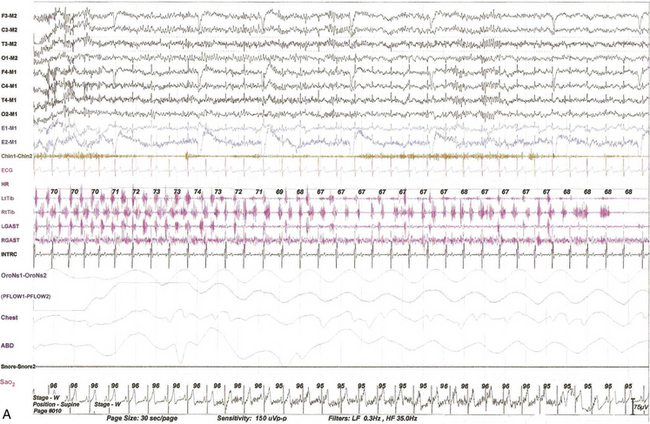

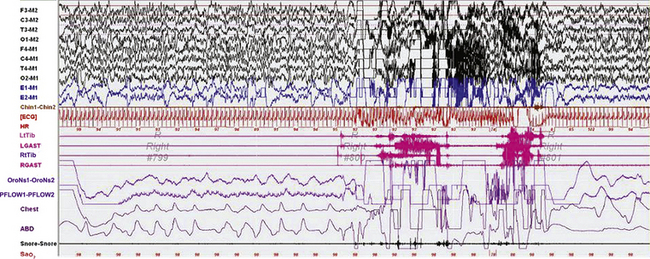

FIGURE 9.3 Periodic limb movements in sleep occurring synchronously in cranially and spinally innervated muscles.

A 60-second epoch from the overnight polysomnogram of a 43-year-old woman referred for excessive leg movements in sleep. Note bursts of periodic limb movements in sleep occurring synchronously in cranially innervated (sternocleidomastoideus, chin, and masseter) and spinally innervated (quadriceps, gastrocnemius, and tibialis) muscles. Top six channels, Electroencephalogram (international nomenclature system); E1-M1 and E2-M1, left and right electro-oculogram, respectively; ECG, electrocardiogram; HR, heart rate; OroNs, oronasal thermistor; PFLOW, nasal pressure transducer; CHEST and ABD, chest and abdominal respiratory effort channels; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation by finger oximetry; Chin1-Chin2, submentalis electromyogram (EMG); Masseter-REF, masseter EMG; RtSterno1-RtSterno2, sternocleidomastoideus EMG; RtBicep1-RtElbow, LtBicep1-LtElbow, right and left biceps brachii EMG; RtTricep1-RtElbow, LtTricep1-LtElbow, right and left triceps EMG;. RtTib, LtTib, right and left tibialis anterior EMG; RGAST, LGAST, right and left gastrocnemius EMG. Also included is a snore channel.

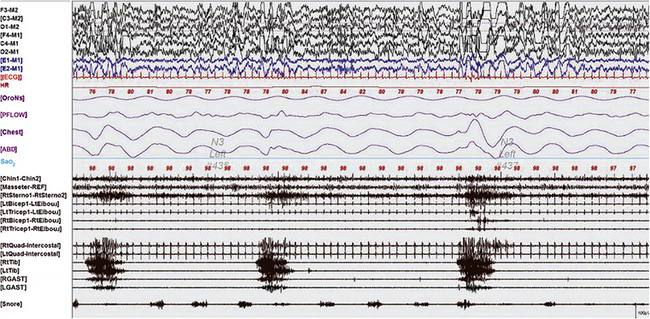

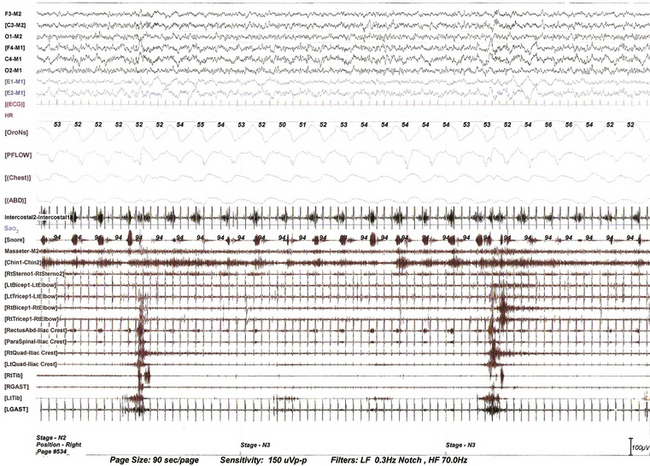

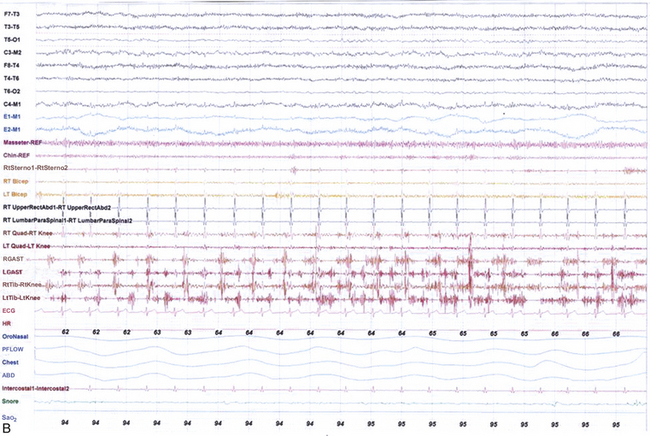

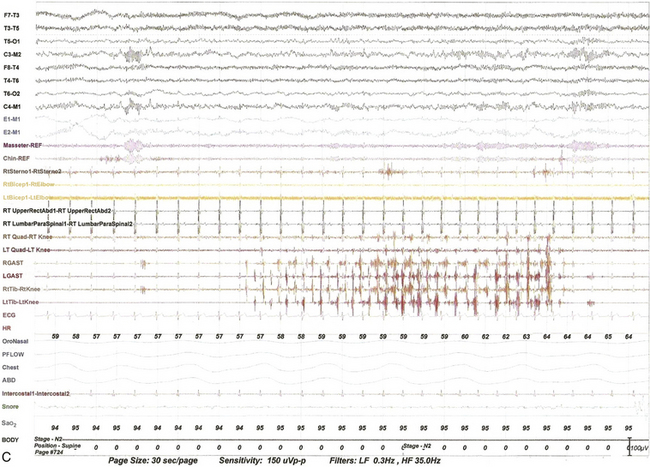

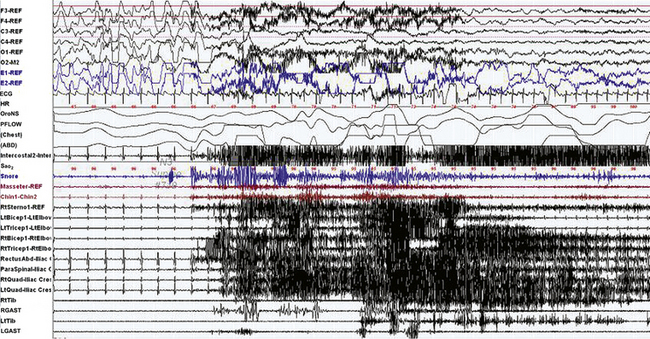

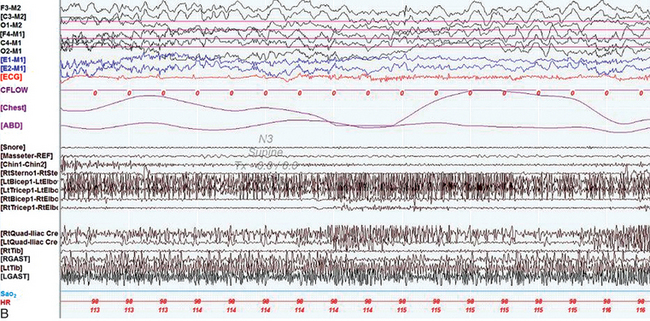

FIGURE 9.4 Propriospinal propagation of periodic limb movements of sleep.

This 90-second epoch of stage N3 sleep is taken from the overnight polysomnographic (PSG) recording using multiple muscle montage in a 66-year-old man with a history of restless legs syndrome (Willis-Ekbom disease), fulfilling all the essential diagnostic criteria for this. Note periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS) originating first in the tibialis anterior and propagating up the spinal cord to the quadriceps muscle and subsequently to the rectus abdominis, paraspinals, and then to the biceps and triceps muscle at a very slow speed (note prolonged interburst intervals between the lower limb, trunk, and upper limb muscles). This suggests propagation along slowly conducting propriospinal pathways. It is not possible to measure exact interburst latencies using our PSG equipment. Note also the inspiratory muscle bursts in cranially innervated muscles (secondary respiratory muscles). The upper rectus abdominis and paraspinal muscles are picking up inspiratory bursts from neighboring intercostal and diaphragmatic muscles. Top six channels, Electroencephalogram (international nomenclature system); E1-M1 and E2-M1, left and right electro-oculogram, respectively; M1, left mastoid; ECG, electrocardiogram; HR, heart rate; OroNs, oronasal thermistor; PFLOW, nasal pressure transducer; Chest and ABD, chest and abdominal respiratory effort channels; Intercostal, intercostal EMG from the right eighth intercostal space; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation by finger oximetry; channels 18 to 32, EMGs from masseter, chin (mentalis muscle), sternocleidomastoideus, biceps, triceps, rectus abdominis (right), paraspinal (right thoracolumbar), quadriceps (left and right), gastrocnemius (RGAST and LGAST), and tibialis anterior (RtTib and LtTib) muscles.

FIGURE 9.5 Expiratory bursts in the rectus abdominis muscle.

A 60-second epoch from the polysomnogram of a 63-year-old woman referred for possible obstructive sleep apnea. This study was performed with a multiple muscle montage. Note the occurrence of alternating muscle bursts in the intercostal electromyogram (EMG) channel (during inspiration, accompanied by snoring as noted in the snore channel) and in the lower rectus abdominis muscle (during expiration). Top six channels, Electroencephalogram (international nomenclature system); E1-M1 and E2-M1, left and right electro-oculogram, respectively; ECG, electrocardiogram; HR, heart rate; OroNs, oronasal thermistor; PFLOW, nasal pressure transducer; Chest and ABD, chest and abdominal respiratory effort channels; Intercostal, right intercostal EMG channel. RectusAbd-Iliac Crest, lower right rectus abdominis EMG channel; Masseter-REF, masseter EMG; Chin1-Chin2, submentalis EMG; Rt Sterno1-Rt Sterno2, right sternocleidomastoideus EMG; Rt Triceps1-RtElbow, Lt Triceps1-LtElbow, right and left triceps EMG; RtTib, LtTib, right and left tibialis anterior EMG; RGAST, LGAST, right and left gastrocnemius EMG; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation by finger oximetry. Also included is a snore channel.

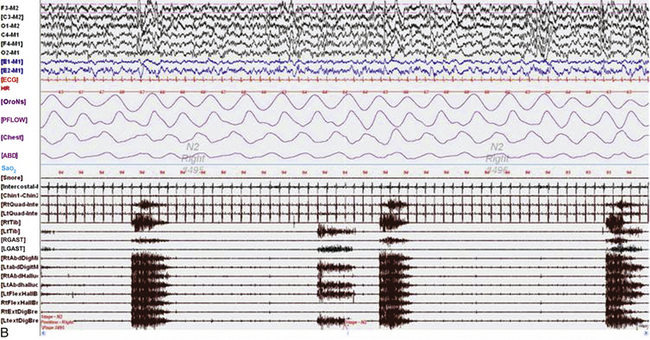

FIGURE 9.6 Painless limbs and moving toes syndrome.

Sixty-second epochs from the overnight polysomnogram with foot montage (see Table 1.6) in a 74-year-old woman with bradykinesia and postural instability. She was on carbidopa/levodopa and complained of painless, involuntary toe movements, which appeared about an hour before her next dose was due and responded to the medication. Note the occurrence of simultaneous dystonic bursts in multiple foot muscles bilaterally occurring in wakefulness (A) and non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep stage N2 (B), but markedly reduced in REM sleep (C). This appears to be a variant of painless limbs and moving toes syndrome. Studies have shown that toe movements in painless limbs and moving toes syndrome may be a combination of synchronous and asynchronous, myoclonic (less than 200 msec) and dystonic (greater than 200 msec, mostly 500 to 1000 msec) bursts; they may persist into various stages of sleep and may be associated with cortical arousals. Top six channels, Electroencephalogram (international nomenclature system); E1-M1 and E2-M1, left and right electro-oculogram, respectively; ECG, electrocardiogram; HR, heart rate; OroNs, oronasal thermistor; PFLOW, nasal pressure transducer; Chest and ABD, chest and abdominal respiratory effort channels; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation by finger oximetry; Chin1-Chin2, submentalis electromyogram (EMG); RtQuad, LtQuad, right and left quadriceps femoris EMG; RtTib, LtTib, right and left tibialis anterior EMG; RGAST, LGAST, right and left gastrocnemius EMG; RtAbdDigM, LtAbdDigMin, right and left abductor digiti minimi EMG; RtAbdHalluc, LtAbdHalluc, right and left abductor hallucis EMG; RtFlexHallB, LtFlexHAllB, right and left flexor hallucis brevis EMG; RtExtDigBre, Lt ExtDigBre, right and left extensor digitorum brevis EMG. Also included are a snore channel and an intercostal EMG (below snore channel).

FIGURE 9.7 A case of rhythmical leg movements with rapid blinking in wakefulness.

A 70-year-old woman with history of insomnia and early morning awakenings. Normal neurological examination with no evidence of Parkinson’s disease or other neurodegenerative disorders. Nocturnal polysomnogram (PSG) revealed mild obstructive sleep apnea. An unusual pattern of episodes of rhythmical leg movements at approximately 0.5 to 1.5 Hz and rapid blinking are noted repeatedly during periods of wakefulness but not during sleep. The significance of these events limited to wakefulness remains uncertain. One such 30-second epoch is demonstrated. Top 10 channels, Electroencephalogram; L-EOG and R-EOG, left and right electro-oculograms; electromyography of chin; Lt/Rt Tib EMG, left and right tibialis anterior EMG; oronasal thermistor; chest and abdomen effort channels; snore monitor; ECG, electrocardiography.

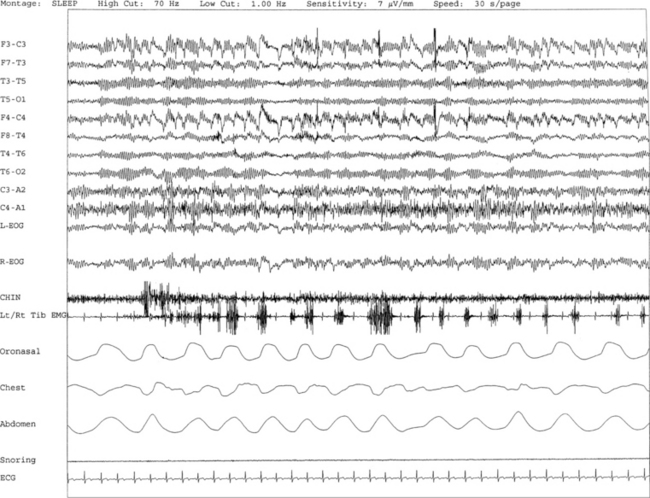

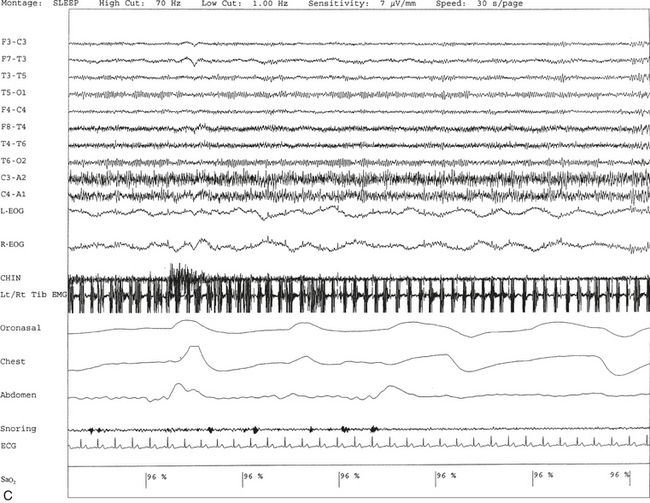

FIGURE 9.8 A case of rhythmical leg movements in wakefulness and sleep unrelated to respiratory events or periodic leg movements in sleep.

A 50-year-old man with history of loud snoring, choking in sleep, and intermittent leg jerking at night. Nocturnal polysomnogram shows the presence of mild sleep apnea with an apnea-hypopnea index of 12.3/hr. Three 30-second epochs from nocturnal polysomnography show bursts of rhythmical foot and leg movements on the left/right tibialis anterior muscle recording channel during stage 2 non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep (A), REM sleep (B), and wakefulness (C). The movement is not associated with respiratory events, oxygen desaturation, or arousal from sleep. Top 10 channels, Electroencephalogram; L-EOG and R-EOG, left and right electro-oculograms; Chin, electromyography (EMG) of chin; Lt/Rt Tib EMG, left/right tibialis anterior EMG; oronasal thermistor; chest and abdomen effort channels; snore monitor; ECG, electrocardiography; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation by finger oximetry.

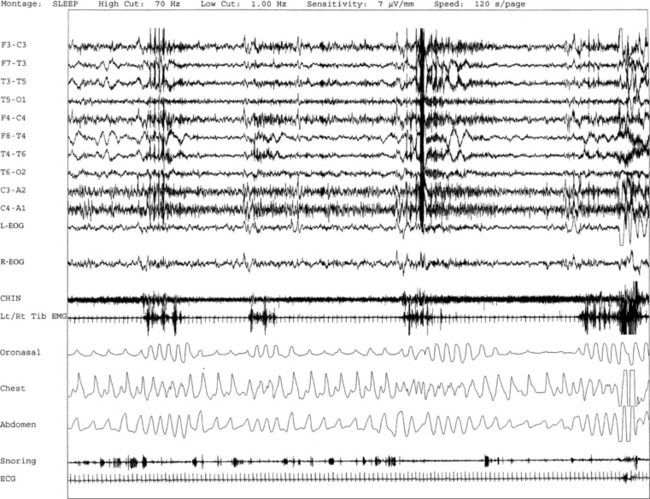

FIGURE 9.9 A case of bruxism associated with arousals following respiratory dysrhythmia.

A 120-second excerpt from polysomnographic (PSG) recording reveals sleep bruxism in a 70-year-old woman with a history of insomnia, early morning awakenings, and excessive daytime sleepiness. Overnight PSG revealed the presence of mild-moderate obstructive sleep apnea with an apnea-hypopnea index of 21.5/hr. Episodes of bruxism are recorded repeatedly as part of the arousal response following respiratory events accompanied by tooth grinding on simultaneous audio-video recording. Respiratory-related limb movements are recorded on tibialis anterior channel in association with the arousal response. PSG sleep bruxism is characterized by a series of teeth grinding associated with rhythmical electromyogram (EMG) artifacts with a frequency of approximately 0.5 to 1.0 Hz in stage 1 non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. Top 10 channels, Electroencephalogram; L-EOG and R-EOG, left and right electro-oculograms; Chin, EMG of chin; Lt/Rt Tib EMG, left/right tibialis anterior EMG; oronasal thermistor; chest and abdomen effort channels; snore monitor; ECG, electrocardiography.

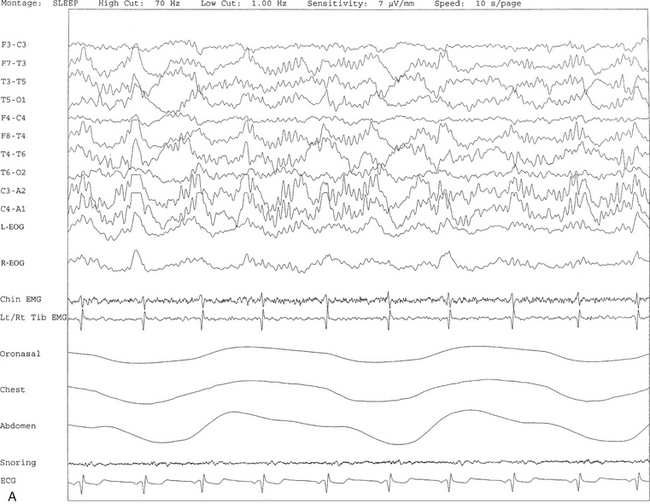

FIGURE 9.10 A case of alpha-delta sleep.

Ten- (A) and 30-second (B) excerpts from a nocturnal polysomnogram (PSG) showing alpha-delta sleep in a 30-year-old man with history of snoring for many years. He denied any history of joint or muscle aches and pains. The alpha frequency is intermixed with and superimposed on underlying delta activity. Alpha-delta sleep denotes a nonspecific sleep architectural change noted in many patients with complaints of muscle aches and fibromyalgia. It is also seen in other conditions and many normal individuals. Top 10 channels, Electroencephalogram; L-EOG and R-EOG, left and right electro-oculograms; Chin, electromyogram (EMG) of chin; Lt/Rt Tib EMG, left/right tibialis anterior EMG; oronasal thermistor; chest and abdomen effort channels; snore monitor; ECG, electrocardiography.

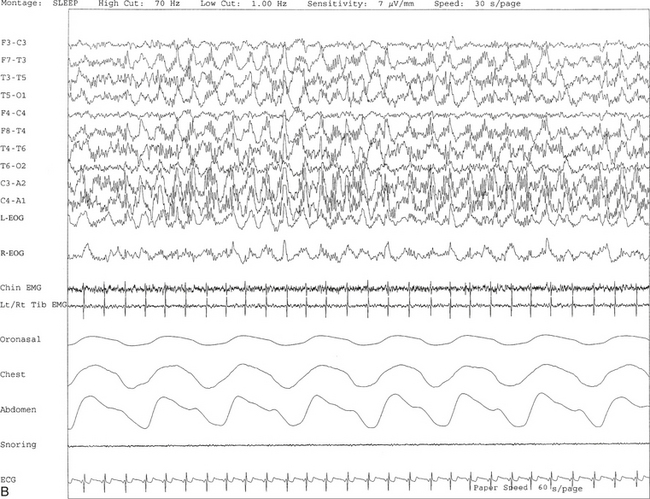

FIGURE 9.11 A case of narcolepsy with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome; polysomnographic (PSG) documentation of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep without atonia in the absence of dream-enacting behavior. A 63-year-old man with episodes of frequent, brief sleep spells during routine daytime activities, for example, relaxing, sitting, or even singing, since early college days with worsening in the last 3 to 4 years. The spells last approximately 5 to 10 minutes and are refreshing on awakening. He denies any history of cataplexy. He experienced sleep paralysis many years ago, but there is no clear history of hypnagogic hallucinations. However, more recently there is a complaint of extremely frightening dreams at night, which are not accompanied by any motor or behavioral disorder. His medical history is significant for adult-onset diabetes mellitus for several years. The neurological examination is significant for evidence suggestive of mild peripheral neuropathy in the legs bilaterally, likely related to diabetes mellitus. Of note, there is no suggestion of a movement disorder on neurological examination. Initial overnight PSG was significant for some nonspecific sleep architectural changes but did not show any evidence of sleep apnea or periodic leg movements in sleep. Multiple sleep latency tests revealed a mean sleep latency of 2.5 minutes consistent with pathological sleepiness. Also, two sleep-onset rapid eye movements suggestive of narcolepsy were recorded. He was started on stimulant treatment and responded well until recently, when he began complaining of excessive daytime sleepiness and increased snoring. A repeat PSG showed recurrent episodes of apneas and hypopneas during non-REM and REM sleep with a moderately severe apnea-hypopnea index of 33/hr, accompanied by mild oxygen desaturation, snoring, and increased arousal index suggestive of sleep apnea syndrome in conjunction with narcolepsy. Interestingly, the PSG showed frequent periods of phasic muscle bursts and intermittent loss of muscle atonia on chin electromyogram (EMG) channel during REM sleep. One such 30-second epoch in REM sleep is shown in this figure. Accompanying motor or behavioral abnormalities were not recorded on simultaneous video monitoring, and patient denied any specific dream recollections. An association between narcolepsy and sleep apnea and that between narcolepsy and REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD) have been described, and close follow-up is indicated to decide if the isolated finding of REM sleep without muscle atonia is a precursor sign of emerging RBD or not. Top 10 channels, Electroencephalogram; L-EOG and R-EOG, left and right electro-oculograms; Chin, EMG of chin; Lt/RtTib EMG, left and right tibialis anterior EMG; PFLOW, nasal pressure transducer; oronasal thermistor; chest and abdomen effort channels; snore monitor; ECG, electrocardiography.

FIGURE 9.12 A case of sleep spindles in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

A 30-second epoch from the overnight polysomnogram (PSG) of a 50-year-old woman with difficulty sleeping, loud snoring, and excessive daytime sleepiness for 5 years. Medical history is significant for chronic headaches and hypothyroidism. Nocturnal PSG showed the presence of mild sleep apnea (no respiratory events are occurring in this epoch) with an apnea-hypopnea index of 10/hr. Note the presence of sleep spindles (box) during REM sleep. Prominent sawtooth waves of REM sleep in C3- and C4-derived electroencephalogram channels, prominent phasic eye movements of REM sleep on electro-oculogram channels, and decreased chin muscle tone characteristic of REM atonia are seen. Sleep spindles, although characteristic of stage N2 sleep, may be seen in REM, especially in the early cycles.

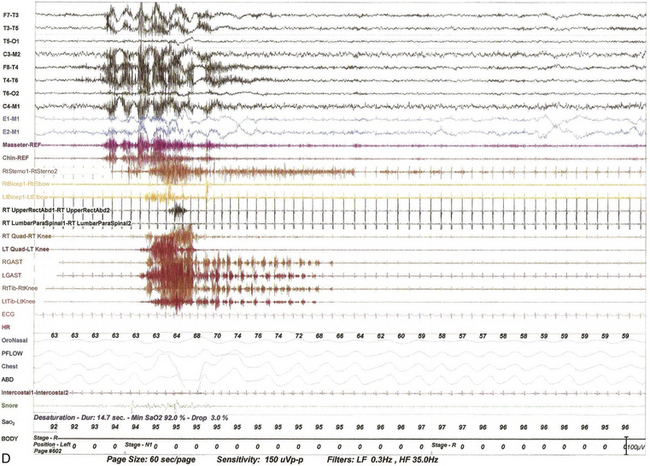

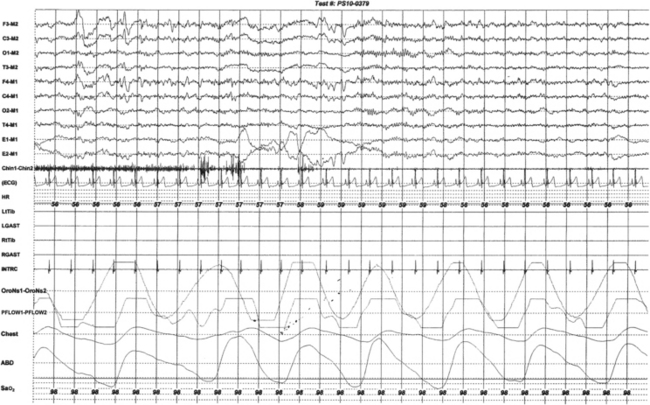

FIGURE 9.13 Alternating leg muscle activation (ALMA) in various stages of sleep.

A, A 30-second epoch in wakefulness showing the presence of ALMA. The patient is a 30-year-old woman with a history of mild snoring and excessive daytime sleepiness. Her polysomnogram (PSG) showed moderate obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) (apnea-hypopnea index [AHI] of 20/hr, severe in supine sleep [AHI of 37/hr]); she was not on antidepressants and did not complain of symptoms suggestive of restless legs syndrome (RLS, recently renamed Willis-Ekbom disease). B to E, Thirty-second epochs from the PSG recorded with multiple muscle montage of a 30-year-old man complaining of “whole body jerking” at night as he is about to fall asleep, consistent with a diagnosis of hypnic jerking. His PSG showed no evidence of OSA, but he was noted to have ALMA in stage N1 (B), stage N2 (C), N3 (not shown), and in REM sleep (D). Also noted was evolution of ALMA into periodic limb movements in sleep stage N2 (E). The clinical significance of ALMA is unknown. A, Top eight channels: Electroencephalogram; E1-M1 and E2-M1, left and right electro-oculograms; Chin1-Chin2, Chin EMG; ECG, electrocardiogram; HR, heart rate; LtTib and RtTib, left and right tibialis anterior EMG; LGAST and RGAST, left and right gastroenemius EMG; INTRC, intercostal (right) EMG; OroNS1-OroNS2, oronasal thermistor; PFLOW1-PFLOW2, nasal pressure transducer; chest and abdonmen (ABD) effort channels; Snor1-Snor2, snore channel; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation. B to E, Top eight channels, electroencephalogram; E1-M1 and E2-M1, left and right electro-oculograms; Masseter-REF, Masseter EMG; Chin-REF, chin electromyogram (EMG); ECG, electrocardiography; HR, heart rate; LtTib and RtTib, left and right tibialis anterior EMG; RGAST and LGAST, right and left gastrocnemius EMG; RtSterno1-RtSterno2, sternocleidomastoideus EMG; RtBicep1-RtElbow, LtBicep1-LtElbow, right and left biceps brachii EMG; RTUpperRectusAbd1-RTUpperRectusAbd2, upper rectus abdominis EMG; RTLumbarParaspinal1-RTLumbarParaspinal2, lumbar paraspinal EMG; RT Quad-RT Knee and LT Quad-LT Knee, right and left quadriceps femoris EMG; oronasal thermistor; nasal pressure transducer; chest and abdomen effort channels; snore monitor; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation.

FIGURE 9.14 Unusual sequence of rapid eye movement (REM) characteristics.

This 30-second epoch from the overnight polysomnogram (PSG) of a 20-year-old man with insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness shows an unusual sequence of events in REM sleep. The usual sequence in REM sleep is muscle atonia, followed by sawtooth waves on the electroencephalography (EEG) channels, and finally rapid eye movements. In this segment REM begins with rapid eye movements followed by muscle atonia. Top eight channels, EEGs (international nomenclature system); E1-M1 and E2-M1, left and right electro-oculograms, respectively; Chin1-Chin2, submentalis EMG; ECG, electrocardiogram; HR, heart rate; LtTib and RtTib, left and right tibialis anterior electromyography (EMG); LGAST and RGAST, left and right gastrocnemius EMG; INTRC, intercostal EMG from the right eighth intercostal space (contains ECG artifact); OroNs, oronasal thermistor; PFLOW, nasal pressure transducer; Chest and ABD, chest and abdominal respiratory effort channels; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation by finger oximetry. Also included is a snore channel.

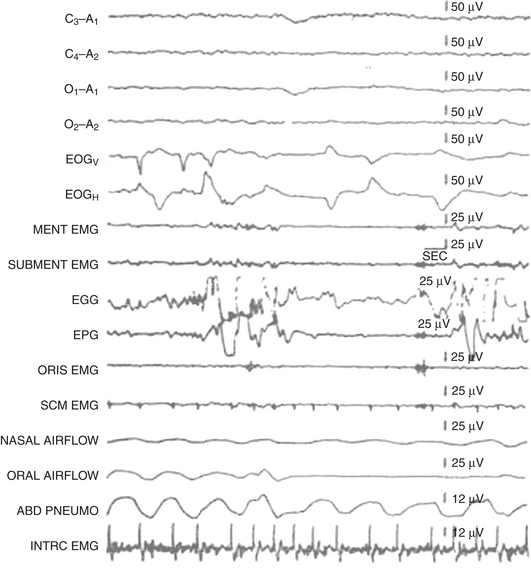

FIGURE 9.15 Rhythmical tongue movements in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

Polysomnographic recording of REM sleep in a healthy 31-year-old man. Rapid eye movements (seen in the electro-oculogram channels) are noted to occur concomitant with complex tongue movements (recorded in the electroglossogram and electropharyngogram channels). Complex tongue movements in REM may occur at the same time as or independent of rapid eye movements. Top four channels (C3-A1, C4-A2, O1-A1, O2-A2), Electroencephalogram; EOGV, vertical electro-oculogram, EOGH, horizontal electro-oculogram. The next six channels represent electromyography from mentalis (MENT), mylohyoid and anterior belly of digastric (SUBMENT), orbicularis oris (ORIS), sternocleidomastoideus (SCM), intercostal muscle (INTRC), electroglossogram (EGG), and electropharyngogram (EPG). Nasal and oral airflow and an abdominal effort belt are also included. (Reproduced with permission from Chokroverty S. Phasic tongue movements in human rapid eye-movement sleep. Neurology. 1980;30[6]:665-668).

FIGURE 9.16 Confusional arousal in rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

A 90-second epoch of REM sleep in a 5-year-old girl referred for a diagnostic polysomnogram (PSG) to exclude obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), with a 2-week history of snoring after developing tonsillitis. The patient had a history of rare nightmares involving monsters, but no history of sleepwalking or confusional arousals. PSG showed mild OSA (apnea-hypopnea index of 2.7/hr). Physical examination showed enlarged, erythematous tonsils. Image shows a spontaneous arousal out of REM sleep, not triggered by a respiratory event, after which she rubbed her eyes, sat up and appeared confused, with rapid eye blinking and looking around the room ![]() (Video Vignette 15). This lasted about 11 seconds, after which she lay down again on her right side. Two similar confusional arousals subsequently occurred in the same REM cycle. REM atonia was well preserved. The patient’s mother, who was in the room, later recalled that the patient awoke that night confused and called for her, but then went back to sleep and did not have any of her typical nightmares. Confusional arousals out of REM sleep are extremely rare. Top eight channels, Electroencephalogram; E1-M1 and E2-M1, left and right electro-oculograms; Chin1-Chin2, chin electromyogram (EMG); ECG, electrocardiography; HR, heart rate; LtTib and RtTib, left and right tibialis anterior EMG; LGAST and RGAST, left and right gastrocnemius EMG; oronasal thermistor; nasal pressure transducer; chest and abdomen effort channels; snore monitor; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation. (Reproduced with permission from Bhat S, Patel D, Rosen D, Chokroverty S. A case of a confusional arousal arising from REM sleep. Sleep Med. 2012;13[3]:317-318.)

(Video Vignette 15). This lasted about 11 seconds, after which she lay down again on her right side. Two similar confusional arousals subsequently occurred in the same REM cycle. REM atonia was well preserved. The patient’s mother, who was in the room, later recalled that the patient awoke that night confused and called for her, but then went back to sleep and did not have any of her typical nightmares. Confusional arousals out of REM sleep are extremely rare. Top eight channels, Electroencephalogram; E1-M1 and E2-M1, left and right electro-oculograms; Chin1-Chin2, chin electromyogram (EMG); ECG, electrocardiography; HR, heart rate; LtTib and RtTib, left and right tibialis anterior EMG; LGAST and RGAST, left and right gastrocnemius EMG; oronasal thermistor; nasal pressure transducer; chest and abdomen effort channels; snore monitor; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation. (Reproduced with permission from Bhat S, Patel D, Rosen D, Chokroverty S. A case of a confusional arousal arising from REM sleep. Sleep Med. 2012;13[3]:317-318.)

FIGURE 9-17 Dream-enacting behavior (DEB) in non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep.

A 30-second epoch from the polysomnogram with multiple muscle channels recorded from a 27-year-old man with sleepwalking, confusional arousals, and nightmares, as well as rare episodes of DEB since early childhood. This event represents an episode of DEB arising out of NREM (stage N3) sleep, with no REM cycle in proximity. He suddenly stood up on the bed and raised his right arm, apparently trying to hold the roof up. Upon awakening by the technician, he was quizzed on dream recall and remembered dreaming that the roof was collapsing and he was trying to hold it up ![]() (Video Vignette 16). REM atonia was preserved. The event was not triggered by a respiratory event. Epileptiform activity was not recorded on the electroencephalogram (EEG) channels. DEB out of NREM sleep is rarely reported. Top six channels, EEG; E1-REF, E2-REF, left and right electro-oculograms; ECG, electrocardiography; HR, heart rate; Chin1-Chin2, chin electromyogram (EMG); LtTib and RtTib, left and right tibialis anterior EMG; LGAST and RGAST, left and right gastrocnemius EMG; oronasal thermistor; nasal pressure transducer; chest and abdomen effort channels; snore monitor; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation. Multiple muscle EMG channels include recordings from the masseter, chin, right sternocleidomastoideus, right and left biceps brachii, right and left triceps, right rectus abdominis, right lumbar paraspinals, and right and left tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles and right and left quadriceps femoris (Quad-iliac excess) muscles. (Reproduced with permission from Bhat S, Chokroverty S, Kabak B, Yang QR, Rosen D. Dream-enacting behavior in non-rapid eye movement sleep. Sleep Med. 2012;13[4]:445-446.)

(Video Vignette 16). REM atonia was preserved. The event was not triggered by a respiratory event. Epileptiform activity was not recorded on the electroencephalogram (EEG) channels. DEB out of NREM sleep is rarely reported. Top six channels, EEG; E1-REF, E2-REF, left and right electro-oculograms; ECG, electrocardiography; HR, heart rate; Chin1-Chin2, chin electromyogram (EMG); LtTib and RtTib, left and right tibialis anterior EMG; LGAST and RGAST, left and right gastrocnemius EMG; oronasal thermistor; nasal pressure transducer; chest and abdomen effort channels; snore monitor; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation. Multiple muscle EMG channels include recordings from the masseter, chin, right sternocleidomastoideus, right and left biceps brachii, right and left triceps, right rectus abdominis, right lumbar paraspinals, and right and left tibialis anterior and gastrocnemius muscles and right and left quadriceps femoris (Quad-iliac excess) muscles. (Reproduced with permission from Bhat S, Chokroverty S, Kabak B, Yang QR, Rosen D. Dream-enacting behavior in non-rapid eye movement sleep. Sleep Med. 2012;13[4]:445-446.)

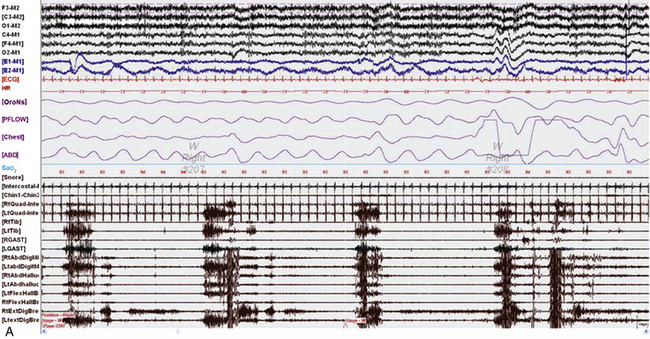

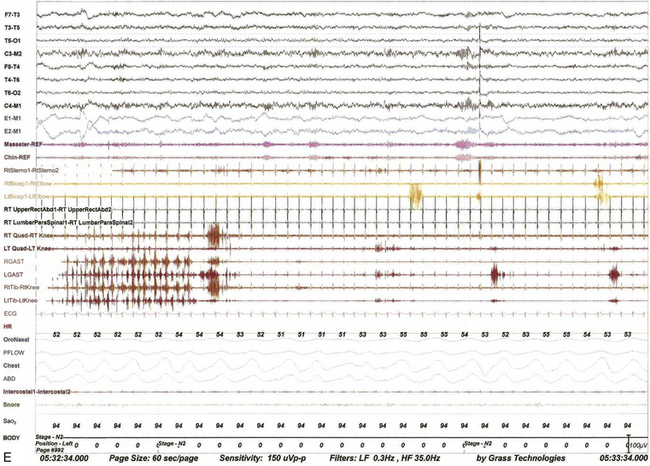

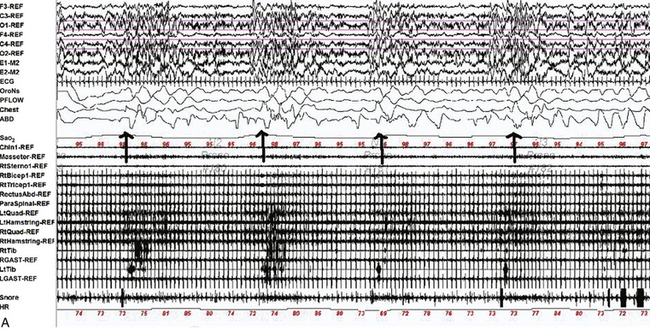

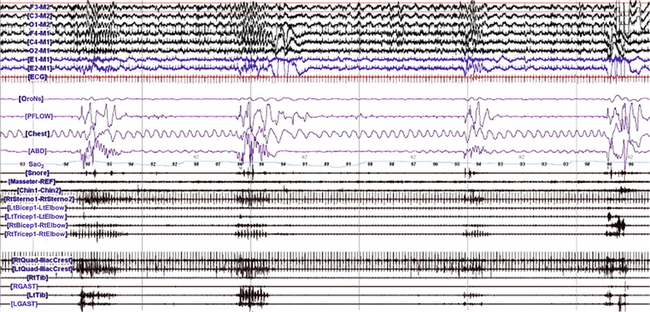

FIGURE 9.18 Multiple causes of complex nocturnal behavior.

A 49-year-old woman with diabetes and a prior diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) was referred with multiple episodes of abnormal behavior in sleep. Her most dramatic episode consisted of a dream of being stuck in a box as the world was apparently ending. Confused, she got out of bed and destroyed property and responded to her daughter with open eyes and a slight smile. She then went outside and threw stones at the neighbor’s door. She subsequently suddenly awoke with no recollection of the event. Overnight polysomnogram revealed moderate OSA with an apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of 16.9/hr (severe in supine sleep with an AHI of 30.6/hr). On the study she had various types of complex body movements, including rhythmic, synchronous abduction/adduction of straight legs, synchronous rotation of straight legs at the hips, independent bilateral rotation of her feet at the ankles, bilateral synchronous flexion-extension of hips and knees, knee flexion with hip abducted (which occurred infrequently and independently on each side), occasional flexion of her left leg at the hip and lifting it up in the air at 90 degrees, bending her right arm behind her head, sitting up confused, drinking soda, pulling wires, fiddling with clothing, tapping her abdomen, and scratching her arms and legs. All these movements occurred at the termination of apneas and hypopneas ![]() (Video Vignette 17) during non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. REM atonia was normally preserved, and electroencephalogram (EEG) showed no epileptiform activity. On a subsequent continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) titration study, 10 cm H2O pressure eliminated OSA and the respiratory-related complex movements. However, around 2:15 AM that night, she became confused, diaphoretic, and tachycardic, pulling off her CPAP mask. She displayed complex dystonic-ballistic movements, different from those noted with respiratory events

(Video Vignette 17) during non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. REM atonia was normally preserved, and electroencephalogram (EEG) showed no epileptiform activity. On a subsequent continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) titration study, 10 cm H2O pressure eliminated OSA and the respiratory-related complex movements. However, around 2:15 AM that night, she became confused, diaphoretic, and tachycardic, pulling off her CPAP mask. She displayed complex dystonic-ballistic movements, different from those noted with respiratory events ![]() (Video Vignette 18). Electroencephalogram (EEG) showed diffuse theta-delta waves and again showed no epileptiform activity. She was taken to the emergency department, where her blood glucose level was undetectable by a portable glucometer. She was treated with intravenous dextrose with normalization of mental status and elimination of complex movements. She had no recollection of this episode. She later admitted to missing morning and afternoon doses of insulin lispro and taking a higher dose along with insulin glargine in the evening to compensate. A, A 120-second epoch from the patient’s original polysomnogram, showing complex behavior occurring at the termination of respiratory events. Top six channels, EEG; E1-M1 and E2-M1, left and right electro-oculogram channels; Chin-REF and Chin1-Chin2, chin electromyogram (EMG). Multiple muscle recording includes EMG activity recorded from the following muscles: right masseter (Masseter-REF), right sternocleidomastoid (RtSterno1-REF), right biceps (RtBicep1-REF), right triceps (RtTricep1-REF), rectus abdominis (RectusAbd-REF), lumbar paraspinals (Paraspinal-REF) and bilateral quadriceps femoris referenced to the respective iliac crests (LtQuad-REF, RtQuad-REF), bilateral hamstrings (LtHamstring-REF, RtHamstring-REF), tibialis anterior (LtTib, RtTib), bilateral gastrocnemius (RGAST-REF, RGAST-REF) muscles. Chest and abdominal effort were measured using respiratory inductive plethysmography belts. Electrocardiography (ECG), arterial oxygen saturation by finger oximetry (SaO2), heart rate (HR), and snore channels are also displayed. OroNS, oronasal theristor; PFLOW, nasal pressure transducer; CFLOW, CPAD flow channel. Bursts of EMG activity in the EMG channels corresponded to complex movements as described. Decreased airflow precedes these events, signifying hypopneas. EEG shows no epileptiform activity. B, A 10-second epoch from the patient’s CPAP titration study. By this time the patient had become confused, tachycardic, and diaphoretic, taken off her CPAP mask, and displayed complex dystonic-ballistic movements, different from those noted with respiratory events. The EEG channels shows showed diffuse theta-delta waves with no evidence of epileptiform activity. (Reproduced with permission from Lysenko L, Bhat S, Patel D, Salim S, Chokroverty S. Complex sleep behavior in a patient with obstructive sleep apnea and nocturnal hypoglycemia: a diagnostic dilemma. Sleep Med. 2012;13[10]:1321-1323.)

(Video Vignette 18). Electroencephalogram (EEG) showed diffuse theta-delta waves and again showed no epileptiform activity. She was taken to the emergency department, where her blood glucose level was undetectable by a portable glucometer. She was treated with intravenous dextrose with normalization of mental status and elimination of complex movements. She had no recollection of this episode. She later admitted to missing morning and afternoon doses of insulin lispro and taking a higher dose along with insulin glargine in the evening to compensate. A, A 120-second epoch from the patient’s original polysomnogram, showing complex behavior occurring at the termination of respiratory events. Top six channels, EEG; E1-M1 and E2-M1, left and right electro-oculogram channels; Chin-REF and Chin1-Chin2, chin electromyogram (EMG). Multiple muscle recording includes EMG activity recorded from the following muscles: right masseter (Masseter-REF), right sternocleidomastoid (RtSterno1-REF), right biceps (RtBicep1-REF), right triceps (RtTricep1-REF), rectus abdominis (RectusAbd-REF), lumbar paraspinals (Paraspinal-REF) and bilateral quadriceps femoris referenced to the respective iliac crests (LtQuad-REF, RtQuad-REF), bilateral hamstrings (LtHamstring-REF, RtHamstring-REF), tibialis anterior (LtTib, RtTib), bilateral gastrocnemius (RGAST-REF, RGAST-REF) muscles. Chest and abdominal effort were measured using respiratory inductive plethysmography belts. Electrocardiography (ECG), arterial oxygen saturation by finger oximetry (SaO2), heart rate (HR), and snore channels are also displayed. OroNS, oronasal theristor; PFLOW, nasal pressure transducer; CFLOW, CPAD flow channel. Bursts of EMG activity in the EMG channels corresponded to complex movements as described. Decreased airflow precedes these events, signifying hypopneas. EEG shows no epileptiform activity. B, A 10-second epoch from the patient’s CPAP titration study. By this time the patient had become confused, tachycardic, and diaphoretic, taken off her CPAP mask, and displayed complex dystonic-ballistic movements, different from those noted with respiratory events. The EEG channels shows showed diffuse theta-delta waves with no evidence of epileptiform activity. (Reproduced with permission from Lysenko L, Bhat S, Patel D, Salim S, Chokroverty S. Complex sleep behavior in a patient with obstructive sleep apnea and nocturnal hypoglycemia: a diagnostic dilemma. Sleep Med. 2012;13[10]:1321-1323.)

FIGURE 9.19 Respiratory related rhythmical movements in sleep.

A, A 180-second excerpt from a portion of an overnight polysomnogram during stage 2 (N2) non–rapid eye movement sleep in a 51-year-old man with obstructive sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, and rhythmic movement disorder showing three episodes of rhythmic electromyographic (EMG) bursts (about 0.75 Hz) and a dystonic EMG burst (last episode toward the end of the tracing) beginning in the right biceps (RtBicep) and right triceps (RtTricep) and spreading to other muscles. These bursts were noted following termination of the apneic events and accompanied by arousals and resumption of normal breathing as well as rhythmical body and head-rolling movements ![]() (Video Vignette 19). Top six channels (international nomenclature), Electroencephalogram; E1-M1, left electro-oculogram; E2-M1, right electro-oculogram; ECG, electrocardiogram; OroNs, oronasal thermistor (air flow); PFLOW, nasal pressure recording for airflow; Chest, thoracic breathing effort; ABD, abdominal breathing effort; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation by finger oximetry; Snore, snoring recording; Masseter, right masseter EMG; Chin, submental EMG; RtSterno, right sternocleidomastoideus EMG; LtBicep, left biceps EMG; LtTricep, left triceps EMG; RtBicep, right biceps EMG; RtTricep, right triceps EMG; RtQuad, right quadriceps (biceps femoris) EMG; LtQuad, left quadriceps EMG; RtTib, right tibialis EMG; RGAST, right gastrocnemius EMG; LtTib, left tibialis EMG; LGAST, left gastrocnemius EMG. (Reproduced with permission from Gharagozlou P, Seyffert M, Santos R, Chokroverty S. Rhythmic movement disorder associated with respiratory arousals and improved by CPAP titration in a patient with restless legs syndrome and sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2009;10[4]:501-503.)

(Video Vignette 19). Top six channels (international nomenclature), Electroencephalogram; E1-M1, left electro-oculogram; E2-M1, right electro-oculogram; ECG, electrocardiogram; OroNs, oronasal thermistor (air flow); PFLOW, nasal pressure recording for airflow; Chest, thoracic breathing effort; ABD, abdominal breathing effort; Sao2, arterial oxygen saturation by finger oximetry; Snore, snoring recording; Masseter, right masseter EMG; Chin, submental EMG; RtSterno, right sternocleidomastoideus EMG; LtBicep, left biceps EMG; LtTricep, left triceps EMG; RtBicep, right biceps EMG; RtTricep, right triceps EMG; RtQuad, right quadriceps (biceps femoris) EMG; LtQuad, left quadriceps EMG; RtTib, right tibialis EMG; RGAST, right gastrocnemius EMG; LtTib, left tibialis EMG; LGAST, left gastrocnemius EMG. (Reproduced with permission from Gharagozlou P, Seyffert M, Santos R, Chokroverty S. Rhythmic movement disorder associated with respiratory arousals and improved by CPAP titration in a patient with restless legs syndrome and sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2009;10[4]:501-503.)

Bhat, S., Chokroverty, S., Kabak, B., Yang, Q. R., Rosen, D. Dream-enacting behavior in non-rapid eye movement sleep. Sleep Med. 2012; 13(4):445–446.

Bhat, S., Patel, D., Rosen, D., Chokroverty, S. A case of a confusional arousal arising from REM sleep. Sleep Med. 2012; 13(3):317–318.

Chokroverty, S. Phasic tongue movements in human rapid eye-movement sleep. Neurology. 1980; 30(6):665–668.

Gharagozlou, P., Seyffert, M., Santos, R., Chokroverty, S. Rhythmic movement disorder associated with respiratory arousals and improved by CPAP titration in a patient with restless legs syndrome and sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2009; 10(4):501–503.

Lysenko, L., Bhat, S., Patel, D., Salim, S., Chokroverty, S. Complex sleep behavior in a patient with obstructive sleep apnea and nocturnal hypoglycemia: a diagnostic dilemma. Sleep Med. 2012; 13(10):1321–1323.

Riar, S., Bhat, S., Kabak, B., Gupta, D., Smith, I., Chokroverty, S. The effect of lateral head position on sleep disordered breathing: a case series. Sleep Med. 2013; 14(2):220–221.