Practice Guidelines for Obstetric Anesthesia: An Updated Report by The American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia*

PRACTICE guidelines are systematically developed recommendations that assist the practitioner and patient in making decisions about health care. These recommendations may be adopted, modified, or rejected according to clinical needs and constraints and are not intended to replace local institutional policies. In addition, practice guidelines are not intended as standards or absolute requirements, and their use cannot guarantee any specific outcome. Practice guidelines are subject to revision as warranted by the evolution of medical knowledge, technology, and practice. They provide basic recommendations that are supported by a synthesis and analysis of the current literature, expert opinion, open forum commentary, and clinical feasibility data.

This update includes data published since the “Practice Guidelines for Obstetrical Anesthesia” were adopted by the American Society of Anesthesiologists in 1998; it also includes data and recommendations for a wider range of techniques than was previously addressed.

Methodology

A Definition of Perioperative Obstetric Anesthesia

For the purposes of these Guidelines, obstetric anesthesia refers to peripartum anesthetic and analgesic activities performed during labor and vaginal delivery, cesarean delivery, removal of retained placenta, and postpartum tubal ligation.

B Purposes of the Guidelines

The purposes of these Guidelines are to enhance the quality of anesthetic care for obstetric patients, improve patient safety by reducing the incidence and severity of anesthesia-related complications, and increase patient satisfaction.

C Focus

These Guidelines focus on the anesthetic management of pregnant patients during labor, nonoperative delivery, operative delivery, and selected aspects of postpartum care and analgesia (i.e., neuraxial opioids for postpartum analgesia after neuraxial anesthesia for cesarean delivery). The intended patient population includes, but is not limited to, intrapartum and postpartum patients with uncomplicated pregnancies or with common obstetric problems. The Guidelines do not apply to patients undergoing surgery during pregnancy, gynecologic patients, or parturients with chronic medical disease (e.g., severe cardiac, renal, or neurologic disease). In addition, these Guidelines do not address (1) postpartum analgesia for vaginal delivery, (2) analgesia after tubal ligation, or (3) postoperative analgesia after general anesthesia (GA) for cesarean delivery.

D Application

These Guidelines are intended for use by anesthesiologists. They also may serve as a resource for other anesthesia providers and healthcare professionals who advise or care for patients who will receive anesthetic care during labor, delivery, and the immediate postpartum period.

E Task Force Members and Consultants

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) appointed a Task Force of 11 members to (1) review the published evidence, (2) obtain the opinion of a panel of consultants including anesthesiologists and nonanesthesiologist physicians concerned with obstetric anesthesia and analgesia, and (3) obtain opinions from practitioners likely to be affected by the Guidelines. The Task Force included anesthesiologists in both private and academic practices from various geographic areas of the United States and two consulting methodologists from the ASA Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters.

The Task Force developed the Guidelines by means of a seven-step process. First, they reached consensus on the criteria for evidence. Second, original published research studies from peer-reviewed journals relevant to obstetric anesthesia were reviewed. Third, the panel of expert consultants was asked to (1) participate in opinion surveys on the effectiveness of various peripartum management strategies and (2) review and comment on a draft of the Guidelines developed by the Task Force. Fourth, opinions about the Guideline recommendations were solicited from active members of the ASA who provide obstetric anesthesia. Fifth, the Task Force held open forums at two major national meetings† to solicit input on its draft recommendations. Sixth, the consultants were surveyed to assess their opinions on the feasibility of implementing the Guidelines. Seventh, all available information was used to build consensus within the Task Force to finalize the Guidelines (Appendix 1).

F Availability and Strength of Evidence

Preparation of these Guidelines followed a rigorous methodologic process. To convey the findings in a concise and easy-to-understand fashion, these Guidelines use several descriptive terms. When sufficient numbers of studies are available for evaluation, the following terms describe the strength of the findings.

Support: Meta-analysis of a sufficient number of randomized controlled trials‡ indicates a statistically significant relationship (P < .01) between a clinical intervention and a clinical outcome.

Suggest: Information from case reports and observational studies permits inference of a relationship between an intervention and an outcome. A meta-analytic assessment of this type of qualitative or descriptive information is not conducted.

Equivocal: Either a meta-analysis has not found significant differences among groups or conditions, or there is insufficient quantitative information to conduct a meta-analysis and information collected from case reports and observational studies does not permit inference of a relationship between an intervention and an outcome.

The lack of scientific evidence in the literature is described by the following terms.

Silent: No identified studies address the specified relationship between an intervention and outcome.

Insufficient: There are too few published studies to investigate a relationship between an intervention and outcome.

Inadequate: The available studies cannot be used to assess the relationship between an intervention and an outcome. These studies either do not meet the criteria for content as defined in the Focus section of these Guidelines, or do not permit a clear causal interpretation of findings due to methodologic concerns.

Formal survey information is collected from consultants and members of the ASA. The following terms describe survey responses for any specified issue. Responses are solicited on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), with a score of 3 being equivocal. Survey responses are summarized based on median values as follows:

Strongly Agree: Median score of 5 (at least 50% of the responses are 5).

Agree: Median score of 4 (at least 50% of the responses are 4 or 4 and 5).

Equivocal: Median score of 3 (at least 50% of the responses are 3, or no other response category or combination of similar categories contain at least 50% of the responses).

Disagree: Median score of 2 (at least 50% of the responses are 2 or 1 and 2).

Strongly Disagree: Median score of 1 (at least 50% of the responses are 1).

Guidelines

I Perianesthetic Evaluation

History and Physical Examination.

Although comparative studies are insufficient to evaluate the peripartum impact of conducting a focused history (e.g., reviewing medical records) or a physical examination, the literature reports certain patient or clinical characteristics that may be associated with obstetric complications. These characteristics include, but are not limited to, preeclampsia, pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders, HELLP syndrome, obesity, and diabetes.

The consultants and ASA members both strongly agree that a directed history and physical examination, as well as communication between anesthetic and obstetric providers, reduces maternal, fetal, and neonatal complications.

Recommendations. The anesthesiologist should conduct a focused history and physical examination before providing anesthesia care. This should include, but is not limited to, a maternal health and anesthetic history, a relevant obstetric history, a baseline blood pressure measurement, and an airway, heart, and lung examination, consistent with the ASA “Practice Advisory for Preanesthesia Evaluation.”§ When a neuraxial anesthetic is planned or placed, the patient's back should be examined.

Recognition of significant anesthetic or obstetric risk factors should encourage consultation between the obstetrician and the anesthesiologist. A communication system should be in place to encourage early and ongoing contact between obstetric providers, anesthesiologists, and other members of the multidisciplinary team.

Intrapartum Platelet Count.

The literature is insufficient to assess whether a routine platelet count can predict anesthesia-related complications in uncomplicated parturients. The literature suggests that a platelet count is clinically useful for parturients with suspected pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders, such as preeclampsia or HELLP syndrome, and for other disorders associated with coagulopathy.

The ASA members are equivocal, but the consultants agree that obtaining a routine intrapartum platelet count does not reduce maternal anesthetic complications. Both the consultants and ASA members agree that, for patients with suspected preeclampsia, a platelet count reduces maternal anesthetic complications. The consultants strongly agree and the ASA members agree that a platelet count reduces maternal anesthetic complications for patients with suspected coagulopathy.

Recommendations. A specific platelet count predictive of neuraxial anesthetic complications has not been determined. The anesthesiologist's decision to order or require a platelet count should be individualized and based on a patient's history, physical examination, and clinical signs. A routine platelet count is not necessary in the healthy parturient.

Blood Type and Screen.

The literature is insufficient to determine whether obtaining a blood type and screen is associated with fewer maternal anesthetic complications. In addition, the literature is insufficient to determine whether a blood cross-match is necessary for healthy and uncomplicated parturients. The consultants and ASA members agree that an intrapartum blood sample should be sent to the blood bank for all parturients.

Recommendations. A routine blood cross-match is not necessary for healthy and uncomplicated parturients for vaginal or operative delivery. The decision whether to order or require a blood type and screen, or cross-match, should be based on maternal history, anticipated hemorrhagic complications (e.g., placenta accreta in a patient with placenta previa and previous uterine surgery), and local institutional policies.

Perianesthetic Recording of the Fetal Heart Rate.

The literature suggests that anesthetic and analgesic agents may influence the fetal heart rate pattern. There is insufficient literature to demonstrate that perianesthetic recording of the fetal heart rate prevents fetal or neonatal complications. Both the consultants and ASA members agree, however, that perianesthetic recording of the fetal heart rate reduces fetal and neonatal complications.

Recommendations. The fetal heart rate should be monitored by a qualified individual before and after administration of neuraxial analgesia for labor. The Task Force recognizes that continuous electronic recording of the fetal heart rate may not be necessary in every clinical setting and may not be possible during initiation of neuraxial anesthesia.

II Aspiration Prevention

Clear Liquids.

There is insufficient published evidence to draw conclusions about the relationship between fasting times for clear liquids and the risk of emesis/reflux or pulmonary aspiration during labor. The consultants and ASA members both agree that oral intake of clear liquids during labor improves maternal comfort and satisfaction. Although the ASA members are equivocal, the consultants agree that oral intake of clear liquids during labor does not increase maternal complications.

Recommendations. The oral intake of modest amounts of clear liquids may be allowed for uncomplicated laboring patients. The uncomplicated patient undergoing elective cesarean delivery may have modest amounts of clear liquids up to 2 h before induction of anesthesia. Examples of clear liquids include, but are not limited to, water, fruit juices without pulp, carbonated beverages, clear tea, black coffee, and sports drinks. The volume of liquid ingested is less important than the presence of particulate matter in the liquid ingested. However, patients with additional risk factors for aspiration (e.g., morbid obesity, diabetes, difficult airway) or patients at increased risk for operative delivery (e.g., nonreassuring fetal heart rate pattern) may have further restrictions of oral intake, determined on a case-by-case basis.

Solids.

A specific fasting time for solids that is predictive of maternal anesthetic complications has not been determined. There is insufficient published evidence to address the safety of any particular fasting period for solids in obstetric patients. The consultants and ASA members both agree that the oral intake of solids during labor increases maternal complications. They both strongly agree that patients undergoing either elective cesarean delivery or postpartum tubal ligation should undergo a fasting period of 6-8 h depending on the type of food ingested (e.g., fat content).∥ The Task Force recognizes that in laboring patients the timing of delivery is uncertain; therefore, compliance with a predetermined fasting period before nonelective surgical procedures is not always possible.

Recommendations. Solid foods should be avoided in laboring patients. The patient undergoing elective surgery (e.g., scheduled cesarean delivery or postpartum tubal ligation) should undergo a fasting period for solids of 6-8 h depending on the type of food ingested (e.g., fat content).∥

Antacids, H2 Receptor Antagonists, and Metoclopramide.

The literature does not sufficiently examine the relationship between reduced gastric acidity and the frequency of emesis, pulmonary aspiration, morbidity, or mortality in obstetric patients who have aspirated gastric contents. Published evidence supports the efficacy of preoperative nonparticulate antacids (e.g., sodium citrate, sodium bicarbonate) in decreasing gastric acidity during the peripartum period. However, the literature is insufficient to examine the impact of nonparticulate antacids on gastric volume. The literature suggests that H2 receptor antagonists are effective in decreasing gastric acidity in obstetric patients and supports the efficacy of metoclopramide in reducing peripartum nausea and vomiting. The consultants and ASA members agree that the administration of a nonparticulate antacid before operative procedures reduces maternal complications.

Recommendations. Before surgical procedures (i.e., cesarean delivery, postpartum tubal ligation), practitioners should consider the timely administration of nonparticulate antacids, H2 receptor antagonists, and/or metoclopramide for aspiration prophylaxis.

III Anesthetic Care for Labor and Vaginal Delivery

Overview.

Not all women require anesthetic care during labor or delivery. For women who request pain relief for labor and/or delivery, there are many effective analgesic techniques available. Maternal request represents sufficient justification for pain relief. In addition, maternal medical and obstetric conditions may warrant the provision of neuraxial techniques to improve maternal and neonatal outcome.

The choice of analgesic technique depends on the medical status of the patient, progress of labor, and resources at the facility. When sufficient resources (e.g., anesthesia and nursing staff) are available, neuraxial catheter techniques should be one of the analgesic options offered. The choice of a specific neuraxial block should be individualized and based on anesthetic risk factors, obstetric risk factors, patient preferences, progress of labor, and resources at the facility.

When neuraxial catheter techniques are used for analgesia during labor or vaginal delivery, the primary goal is to provide adequate maternal analgesia with minimal motor block (e.g., achieved with the administration of local anesthetics at low concentrations with or without opioids).

When a neuraxial technique is chosen, appropriate resources for the treatment of complications (e.g., hypotension, systemic toxicity, high spinal anesthesia) should be available. If an opioid is added, treatments for related complications (e.g., pruritus, nausea, respiratory depression) should be available. An intravenous infusion should be established before the initiation of neuraxial analgesia or anesthesia and maintained throughout the duration of the neuraxial analgesic or anesthetic. However, administration of a fixed volume of intravenous fluid is not required before neuraxial analgesia is initiated.

Timing of Neuraxial Analgesia and Outcome of Labor.

Meta-analysis of the literature determined that the timing of neuraxial analgesia does not affect the frequency of cesarean delivery. The literature also suggests that other delivery outcomes (i.e., spontaneous or instrumented) are also unaffected. The consultants strongly agree and the ASA members agree that early initiation of epidural analgesia (i.e., at cervical dilations of less than 5 cm vs. equal to or greater than 5 cm) improves analgesia. They both disagree that motor block or maternal, fetal, or neonatal side effects are increased by early administration.

Recommendations. Patients in early labor (i.e., < 5 cm dilation) should be given the option of neuraxial analgesia when this service is available. Neuraxial analgesia should not be withheld on the basis of achieving an arbitrary cervical dilation, and should be offered on an individualized basis. Patients may be reassured that the use of neuraxial analgesia does not increase the incidence of cesarean delivery.

Neuraxial Analgesia and Trial of Labor after Previous Cesarean Delivery.

Nonrandomized comparative studies suggest that epidural analgesia may be used in a trial of labor for previous cesarean delivery patients without adversely affecting the incidence of vaginal delivery. Randomized comparisons of epidural versus other anesthetic techniques were not found. The consultants and ASA members agree that neuraxial techniques improve the likelihood of vaginal delivery for patients attempting vaginal birth after cesarean delivery.

Recommendations. Neuraxial techniques should be offered to patients attempting vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. For these patients, it is also appropriate to consider early placement of a neuraxial catheter that can be used later for labor analgesia, or for anesthesia in the event of operative delivery.

Early Insertion of a Spinal or Epidural Catheter for Complicated Parturients.

The literature is insufficient to assess whether, when caring for the complicated parturient, the early insertion of a spinal or epidural catheter, with later administration of analgesia, improves maternal or neonatal outcomes. The consultants and ASA members agree that early insertion of a spinal or epidural catheter for complicated parturients reduces maternal complications.

Recommendations. Early insertion of a spinal or epidural catheter for obstetric (e.g., twin gestation or preeclampsia) or anesthetic indications (e.g., anticipated difficult airway or obesity) should be considered to reduce the need for GA if an emergent procedure becomes necessary. In these cases, the insertion of a spinal or epidural catheter may precede the onset of labor or a patient's request for labor analgesia.

Continuous Infusion Epidural Analgesia

CIE Compared with Parenteral Opioids. The literature suggests that the use of continuous infusion epidural (CIE) local anesthetics with or without opioids provides greater quality of analgesia compared with parenteral (i.e., intravenous or intramuscular) opioids. The consultants and ASA members strongly agree that CIE local anesthetics with or without opioids provide improved analgesia compared with parenteral opioids.

Meta-analysis of the literature indicates that there is a longer duration of labor, with an average duration of 24 min for the second stage, and a lower frequency of spontaneous vaginal delivery when continuous epidural local anesthetics are administered compared with intravenous opioids. Meta-analysis of the literature determined that there are no differences in the frequency of cesarean delivery. Neither the consultants nor ASA members agree that CIE local anesthetics compared with parenteral opioids significantly (1) increase the duration of labor, (2) decrease the chance of spontaneous delivery, (3) increase maternal side effects, or (4) increase fetal and neonatal side effects.

CIE Compared with Single-injection Spinal. There is insufficient literature to assess the analgesic efficacy of CIE local anesthetics with or without opioids compared to single-injection spinal opioids with or without local anesthetics. The consultants are equivocal, but the ASA members agree that CIE local anesthetics improve analgesia compared with single-injection spinal opioids; both the consultants and ASA members are equivocal regarding the frequency of motor block. The consultants are equivocal, but the ASA members disagree that the use of CIE compared with single-injection spinal opioids increases the duration of labor. They both disagree that CIE local anesthetics with or without opioids compared to single-injection spinal opioids with or without local anesthetics decreases the likelihood of spontaneous delivery or increases maternal, fetal, or neonatal side effects.

CIE with and without Opioids. The literature supports the induction of analgesia using epidural local anesthetics combined with opioids compared with equal concentrations of epidural local anesthetics without opioids for improved quality and longer duration of analgesia. The consultants strongly agree and the ASA members agree that the addition of opioids to epidural local anesthetics improves analgesia; they both disagree that fetal or neonatal side effects are increased. The consultants disagree, but the ASA members are equivocal regarding whether the addition of opioids increases maternal side effects.

The literature is insufficient to determine whether induction of analgesia using local anesthetics with opioids compared with higher concentrations of epidural local anesthetics without opioids provides improved quality or duration of analgesia. The consultants and ASA members are equivocal regarding improved analgesia, and they both disagree that maternal, fetal, or neonatal side effects are increased using lower concentrations of epidural local anesthetics with opioids.

For maintenance of analgesia, the literature suggests that there are no differences in the analgesic efficacy of low concentrations of epidural local anesthetics with opioids compared with higher concentrations of epidural local anesthetics without opioids. The Task Force notes that the addition of an opioid to a local anesthetic infusion allows an even lower concentration of local anesthetic for providing equally effective analgesia. However, the literature is insufficient to examine whether a bupivacaine infusion concentration of less than or equal to 0.125% with an opioid provides comparable or improved analgesia compared with a bupivacaine concentration greater than 0.125% without an opioid.# Meta-analysis of the literature determined that low concentrations of epidural local anesthetics with opioids compared with higher concentrations of epidural local anesthetics without opioids are associated with reduced motor block. No differences in the duration of labor, mode of delivery, or neonatal outcomes are found when epidural local anesthetics with opioids are compared with epidural local anesthetics without opioids. The literature is insufficient to determine the effects of epidural local anesthetics with opioids on other maternal outcomes (e.g., hypotension, nausea, pruritus, respiratory depression, urinary retention).

The consultants and ASA members both agree that maintenance of epidural analgesia using low concentrations of local anesthetics with opioids provides improved analgesia compared with higher concentrations of local anesthetics without opioids. The consultants agree, but the ASA members are equivocal regarding the improved likelihood of spontaneous delivery when lower concentrations of local anesthetics with opioids are used. The consultants strongly agree and the ASA members agree that motor block is reduced. They agree that maternal side effects are reduced with this drug combination. They are both equivocal regarding a reduction in fetal and neonatal side effects.

Recommendations. The selected analgesic/anesthetic technique should reflect patient needs and preferences, practitioner preferences or skills, and available resources. The continuous epidural infusion technique may be used for effective analgesia for labor and delivery. When a continuous epidural infusion of local anesthetic is selected, an opioid may be added to reduce the concentration of local anesthetic, improve the quality of analgesia, and minimize motor block.

Adequate analgesia for uncomplicated labor and delivery should be administered with the secondary goal of producing as little motor block as possible by using dilute concentrations of local anesthetics with opioids. The lowest concentration of local anesthetic infusion that provides adequate maternal analgesia and satisfaction should be administered. For example, an infusion concentration greater than 0.125% bupivacaine is unnecessary for labor analgesia in most patients.

Single-injection Spinal Opioids with or without Local Anesthetics.

The literature suggests that spinal opioids with or without local anesthetics provide effective analgesia during labor without altering the incidence of neonatal complications. There is insufficient literature to compare spinal opioids with parenteral opioids. There is also insufficient literature to compare single-injection spinal opioids with local anesthetics versus single-injection spinal opioids without local anesthetics.

The consultants strongly agree and the ASA members agree that spinal opioids provide improved analgesia compared with parenteral opioids. They both disagree that, compared with parenteral opioids, spinal opioids increase the duration of labor, decrease the chance of spontaneous delivery, or increase fetal and neonatal side effects. The consultants are equivocal, but the ASA members disagree that maternal side effects are increased with spinal opioids.

Compared with spinal opioids without local anesthetics, the consultants and ASA members both agree that spinal opioids with local anesthetics provide improved analgesia. They both disagree that the chance of spontaneous delivery is decreased and that fetal and neonatal side effects are increased. They are both equivocal regarding an increase in maternal side effects. However, they both agree that motor block is increased when local anesthetics are added to spinal opioids. Finally, the consultants disagree, but the ASA members are equivocal regarding an increase in the duration of labor.

Recommendations. Single-injection spinal opioids with or without local anesthetics may be used to provide effective, although time-limited, analgesia for labor when spontaneous vaginal delivery is anticipated. If labor is expected to last longer than the analgesic effects of the spinal drugs chosen or if there is a good possibility of operative delivery, a catheter technique instead of a single injection technique should be considered. A local anesthetic may be added to a spinal opioid to increase duration and improve quality of analgesia. The Task Force notes that the rapid onset of analgesia provided by single-injection spinal techniques may be advantageous for selected patients (e.g., those in advanced labor).

Pencil-point Spinal Needles.

The literature supports the use of pencil-point spinal needles compared with cutting-bevel spinal needles to reduce the frequency of post–dural puncture headache. The consultants and ASA members both strongly agree that the use of pencil-point spinal needles reduces maternal complications.

Recommendations. Pencil-point spinal needles should be used instead of cutting-bevel spinal needles to minimize the risk of post–dural puncture headache.

Combined Spinal-Epidural Analgesia.

The literature supports a faster onset time and equivalent analgesia with combined spinal-epidural (CSE) local anesthetics with opioids versus epidural local anesthetics with opioids. The literature is equivocal regarding the impact of CSE versus epidural local anesthetics with opioids on maternal satisfaction with analgesia, mode of delivery, hypotension, motor block, nausea, fetal heart rate changes, and Apgar scores. Meta-analysis of the literature indicates that the frequency of pruritus is increased with CSE.

The consultants and ASA members both agree that CSE local anesthetics with opioids provide improved early analgesia compared with epidural local anesthetics with opioids. They are equivocal regarding the impact of CSE with opioids on overall analgesic efficacy, duration of labor, and motor block. The consultants and ASA members both disagree that CSE increases the risk of fetal or neonatal side effects. The consultants disagree, but the ASA members are equivocal regarding whether CSE increases the incidence of maternal side effects.

Recommendations. Combined spinal-epidural techniques may be used to provide effective and rapid onset of analgesia for labor.

Patient-controlled Epidural Analgesia.

The literature supports the efficacy of patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) versus CIE in providing equivalent analgesia with reduced drug consumption. Meta-analysis of the literature indicates that the duration of labor is longer with PCEA compared with CIE for the first stage (e.g., an average of 36 min) but not the second stage of labor. Meta-analysis of the literature also determined that mode of delivery, frequency of motor block, and Apgar scores are equivalent when PCEA administration is compared with CIE. The literature supports greater analgesic efficacy for PCEA with a background infusion compared with PCEA without a background infusion; meta-analysis of the literature also indicates no differences in the mode of delivery or frequency of motor block. The consultants and ASA members agree that PCEA compared with CIE improves analgesia and reduces the need for anesthetic interventions; they also agree that PCEA improves maternal satisfaction. The consultants and ASA members are equivocal regarding a reduction in motor block, an increased likelihood of spontaneous delivery, or a decrease in maternal side effects with PCEA compared with CIE. They both agree that PCEA with a background infusion improves analgesia, improves maternal satisfaction, and reduces the need for anesthetic intervention. The ASA members are equivocal, but the consultants disagree that a background infusion decreases the chance of spontaneous delivery or increases maternal side effects. The consultants and ASA members are equivocal regarding the effect of a background infusion on the incidence of motor block.

Recommendations. Patient-controlled epidural analgesia may be used to provide an effective and flexible approach for the maintenance of labor analgesia. The Task Force notes that the use of PCEA may be preferable to fixed-rate CIE for providing fewer anesthetic interventions and reduced dosages of local anesthetics. PCEA may be used with or without a background infusion.

IV Removal of Retained Placenta

Anesthetic Techniques.

The literature is insufficient to assess whether a particular type of anesthetic is more effective than another for removal of retained placenta. The consultants strongly agree and the ASA members agree that, if a functioning epidural catheter is in place and the patient is hemodynamically stable, epidural anesthesia is the preferred technique for the removal of retained placenta. The consultants and ASA members both agree that, in cases involving major maternal hemorrhage, GA is preferred over neuraxial anesthesia.

Recommendations. The Task Force notes that, in general, there is no preferred anesthetic technique for removal of retained placenta. However, if an epidural catheter is in place and the patient is hemodynamically stable, epidural anesthesia is preferable. Hemodynamic status should be assessed before administering neuraxial anesthesia. Aspiration prophylaxis should be considered. Sedation/analgesia should be titrated carefully due to the potential risks of respiratory depression and pulmonary aspiration during the immediate postpartum period. In cases involving major maternal hemorrhage, GA with an endotracheal tube may be preferable to neuraxial anesthesia.

Uterine Relaxation.

The literature suggests that nitroglycerin is effective for uterine relaxation during the removal of retained placenta. The consultants and ASA members both agree that the administration of nitroglycerin for uterine relaxation improves success in removing a retained placenta.

Recommendations. Nitroglycerin may be used as an alternative to terbutaline sulfate or general endotracheal anesthesia with halogenated agents for uterine relaxation during removal of retained placental tissue. Initiating treatment with incremental doses of intravenous or sublingual (i.e., metered dose spray) nitroglycerin may relax the uterus sufficiently while minimizing potential complications (e.g., hypotension).

V Anesthetic Choices for Cesarean Delivery

Equipment, Facilities, and Support Personnel.

The literature is insufficient to evaluate the benefit of providing equipment, facilities and support personnel in the labor and delivery operating suite comparable to that available in the main operating suite. The consultants and ASA members strongly agree that the available equipment, facilities, and support personnel should be comparable.

Recommendations. Equipment, facilities, and support personnel available in the labor and delivery operating suite should be comparable to those available in the main operating suite. Resources for the treatment of potential complications (e.g., failed intubation, inadequate analgesia, hypotension, respiratory depression, pruritus, vomiting) should also be available in the labor and delivery operating suite. Appropriate equipment and personnel should be available to care for obstetric patients recovering from major neuraxial anesthesia or GA.

General, Epidural, Spinal, or Combined Spinal-Epidural Anesthesia.

The literature suggests that induction-to-delivery times for GA are lower compared with epidural or spinal anesthesia and that a higher frequency of maternal hypotension may be associated with epidural or spinal techniques. Meta-analysis of the literature found that Apgar scores at 1 and 5 min are lower for GA compared with epidural anesthesia and suggests that Apgar scores are lower for GA versus spinal anesthesia. The literature is equivocal regarding differences in umbilical artery pH values when GA is compared with epidural or spinal anesthesia.

The consultants and ASA members agree that GA reduces the time to skin incision when compared with either epidural or spinal anesthesia; they also agree that GA increases maternal complications. The consultants are equivocal and the ASA members agree that GA increases fetal and neonatal complications. The consultants and ASA members both agree that epidural anesthesia increases the time to skin incision and decreases the quality of anesthesia compared with spinal anesthesia. They both disagree that epidural anesthesia increases maternal complications.

When spinal anesthesia is compared with epidural anesthesia, meta-analysis of the literature found that induction-to-delivery times are shorter for spinal anesthesia. The literature is equivocal regarding hypotension, umbilical pH values, and Apgar scores. The consultants and ASA members agree that epidural anesthesia increases time to skin incision and reduces the quality of anesthesia when compared with spinal anesthesia. They both disagree that epidural anesthesia increases maternal complications.

When CSE is compared with epidural anesthesia, meta-analysis of the literature found no differences in the frequency of hypotension or in 1-min Apgar scores; the literature is insufficient to evaluate outcomes associated with the use of CSE compared with spinal anesthesia. The consultants and ASA members agree that CSE anesthesia improves anesthesia and reduces time to skin incision when compared with epidural anesthesia. The ASA members are equivocal, but the consultants disagree that maternal side effects are reduced. The consultants and ASA members both disagree that CSE improves anesthesia compared with spinal anesthesia. The ASA members are equivocal, but the consultants disagree that maternal side effects are reduced. The consultants strongly agree and the ASA members agree that CSE compared with spinal anesthesia increases flexibility of prolonged procedures, and they both agree that the time to skin incision is increased.

Recommendations. The decision to use a particular anesthetic technique for cesarean delivery should be individualized, based on several factors. These include anesthetic, obstetric, or fetal risk factors (e.g., elective vs. emergency), the preferences of the patient, and the judgment of the anesthesiologist. Neuraxial techniques are preferred to GA for most cesarean deliveries. An indwelling epidural catheter may provide equivalent onset of anesthesia compared with initiation of spinal anesthesia for urgent cesarean delivery. If spinal anesthesia is chosen, pencil-point spinal needles should be used instead of cutting-bevel spinal needles. However, GA may be the most appropriate choice in some circumstances (e.g., profound fetal bradycardia, ruptured uterus, severe hemorrhage, severe placental abruption). Uterine displacement (usually left displacement) should be maintained until delivery regardless of the anesthetic technique used.

Intravenous Fluid Preloading.

The literature supports and the consultants and ASA members agree that intravenous fluid preloading for spinal anesthesia reduces the frequency of maternal hypotension when compared with no fluid preloading.

Recommendations. Intravenous fluid preloading may be used to reduce the frequency of maternal hypotension after spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery. Although fluid preloading reduces the frequency of maternal hypotension, initiation of spinal anesthesia should not be delayed to administer a fixed volume of intravenous fluid.

Ephedrine or Phenylephrine.

The literature supports the administration of ephedrine and suggests that phenylephrine is effective in reducing maternal hypotension during neuraxial anesthesia for cesarean delivery. The literature is equivocal regarding the relative frequency of patients with breakthrough hypotension when infusions of ephedrine are compared with phenylephrine; however, lower umbilical cord pH values are reported after ephedrine administration. The consultants agree and the ASA members strongly agree that ephedrine is acceptable for treating hypotension during neuraxial anesthesia. The consultants strongly agree and the ASA members agree that phenylephrine is an acceptable agent for the treatment of hypotension.

Recommendations. Intravenous ephedrine and phenylephrine are both acceptable drugs for treating hypotension during neuraxial anesthesia. In the absence of maternal bradycardia, phenylephrine may be preferable because of improved fetal acid-base status in uncomplicated pregnancies.

Neuraxial Opioids for Postoperative Analgesia.

For improved postoperative analgesia after cesarean delivery during epidural anesthesia, the literature supports the use of epidural opioids compared with intermittent injections of intravenous or intramuscular opioids. However, a higher frequency of pruritus was found with epidural opioids. The literature is insufficient to evaluate the impact of epidural opioids compared with intravenous PCA. In addition, the literature is insufficient to evaluate spinal opioids compared with parenteral opioids. The consultants strongly agree and the ASA members agree that neuraxial opioids for postoperative analgesia improve analgesia and maternal satisfaction.

Recommendations. For postoperative analgesia after neuraxial anesthesia for cesarean delivery, neuraxial opioids are preferred over intermittent injections of parenteral opioids.

VI Postpartum Tubal Ligation

There is insufficient literature to evaluate the benefits of neuraxial anesthesia compared with GA for postpartum tubal ligation. In addition, the literature is insufficient to evaluate the impact of the timing of a postpartum tubal ligation on maternal outcome. The consultants and ASA members both agree that neuraxial anesthesia for postpartum tubal ligation reduces complications compared with GA. The ASA members are equivocal but the consultants agree that a postpartum tubal ligation within 8 h of delivery does not increase maternal complications.

Recommendations. For postpartum tubal ligation, the patient should have no oral intake of solid foods within 6–8 h of the surgery, depending on the type of food ingested (e.g., fat content). Aspiration prophylaxis should be considered. Both the timing of the procedure and the decision to use a particular anesthetic technique (i.e., neuraxial vs. general) should be individualized, based on anesthetic risk factors, obstetric risk factors (e.g., blood loss), and patient preferences. However, neuraxial techniques are preferred to GA for most postpartum tubal ligations. The anesthesiologist should be aware that gastric emptying will be delayed in patients who have received opioids during labor, and that an epidural catheter placed for labor may be more likely to fail with longer postdelivery time intervals. If a postpartum tubal ligation is to be performed before the patient is discharged from the hospital, the procedure should not be attempted at a time when it might compromise other aspects of patient care on the labor and delivery unit.

VII Management of Obstetric and Anesthetic Emergencies

Resources for Management of Hemorrhagic Emergencies.

Observational studies and case reports suggest that the availability of resources for hemorrhagic emergencies may be associated with reduced maternal complications. The consultants and ASA members both strongly agree that the availability of resources for managing hemorrhagic emergencies reduces maternal complications.

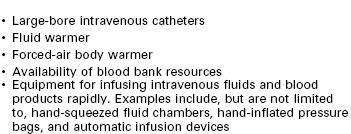

Recommendations. Institutions providing obstetric care should have resources available to manage hemorrhagic emergencies (table 1). In an emergency, the use of type-specific or O negative blood is acceptable. In cases of intractable hemorrhage when banked blood is not available or the patient refuses banked blood, intraoperative cell-salvage should be considered if available.

Central Invasive Hemodynamic Monitoring.

There is insufficient literature to examine whether pulmonary artery catheterization is associated with improved maternal, fetal, or neonatal outcomes in patients with pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders. The literature is silent regarding the management of obstetric patients with central venous catheterization alone. The consultants and ASA members agree that the routine use of central venous or pulmonary artery catheterization does not reduce maternal complications in severely preeclamptic patients.

Recommendations. The decision to perform invasive hemodynamic monitoring should be individualized and based on clinical indications that include the patient's medical history and cardiovascular risk factors. The Task Force recognizes that not all practitioners have access to resources for use of central venous or pulmonary artery catheters in obstetric units.

Equipment for Management of Airway Emergencies.

Case reports suggest that the availability of equipment for the management of airway emergencies may be associated with reduced maternal, fetal, and neonatal complications. The consultants and ASA members both strongly agree that the immediate availability of equipment for the management of airway emergencies reduces maternal, fetal, and neonatal complications.

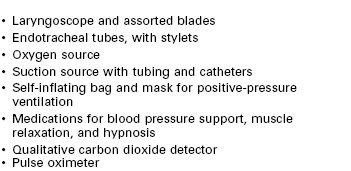

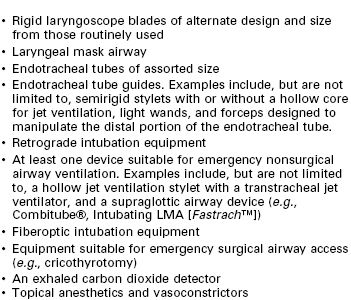

Recommendations. Labor and delivery units should have personnel and equipment readily available to manage airway emergencies, to include a pulse oximeter and qualitative carbon dioxide detector, consistent with the ASA Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway.** Basic airway management equipment should be immediately available during the provision of neuraxial analgesia (table 2). In addition, portable equipment for difficult airway management should be readily available in the operative area of labor and delivery units (table 3). The anesthesiologist should have a preformulated strategy for intubation of the difficult airway. When tracheal intubation has failed, ventilation with mask and cricoid pressure, or with a laryngeal mask airway or supraglottic airway device (e.g., Combitube®, Intubating LMA [Fastrach™]) should be considered for maintaining an airway and ventilating the lungs. If it is not possible to ventilate or awaken the patient, an airway should be created surgically.

TABLE 2

Suggested Resources for Airway Management during Initial Provision of Neuraxial Anesthesia

The items listed represent suggestions. The items should be customized to meet the specific needs, preferences, and skills of the practitioner and health-care facility.

TABLE 3

Suggested Contents of a Portable Storage Unit for Difficult Airway Management for Cesarean Delivery Rooms

The items listed represent suggestions. The items should be customized to meet the specific needs, preferences, and skills of the practitioner and health-care facility.

Adapted from Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology 2003; 98:1269–77.

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation.

The literature is insufficient to evaluate the efficacy of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the obstetric patient during labor and delivery. In cases of cardiac arrest, the American Heart Association has stated that 4–5 min is the maximum time rescuers will have to determine whether the arrest can be reversed by Basic Life Support and Advanced Cardiac Life Support interventions.†† Delivery of the fetus may improve cardiopulmonary resuscitation of the mother by relieving aortocaval compression. The American Heart Association further notes that “the best survival rate for infants > 24 to 25 weeks in gestation occurs when the delivery of the infant occurs no more than 5 min after the mother's heart stops beating. This typically requires that the provider begin the hysterotomy about 4 min after cardiac arrest.”†† The consultants and ASA members both strongly agree that the immediate availability of basic and advanced life-support equipment in the labor and delivery suite reduces maternal, fetal, and neonatal complications.

Recommendations. Basic and advanced life-support equipment should be immediately available in the operative area of labor and delivery units. If cardiac arrest occurs during labor and delivery, standard resuscitative measures should be initiated. In addition, uterine displacement (usually left displacement) should be maintained. If maternal circulation is not restored within 4 min, cesarean delivery should be performed by the obstetrics team.

Appendix 1: Summary of Recommendations

I Perianesthetic Evaluation

• Conduct a focused history and physical examination before providing anesthesia care

• Maternal health and anesthetic history

• Airway and heart and lung examination

• Baseline blood pressure measurement

• Back examination when neuraxial anesthesia is planned or placed

• A communication system should be in place to encourage early and ongoing contact between obstetric providers, anesthesiologists, and other members of the multidisciplinary team

• Order or require a platelet count based on a patient's history, physical examination, and clinical signs; a routine intrapartum platelet count is not necessary in the healthy parturient

• Order or require an intrapartum blood type and screen or cross-match based on maternal history, anticipated hemorrhagic complications (e.g., placenta accreta in a patient with placenta previa and previous uterine surgery), and local institutional policies; a routine blood cross-match is not necessary for healthy and uncomplicated parturients

• The fetal heart rate should be monitored by a qualified individual before and after administration of neuraxial analgesia for labor; continuous electronic recording of the fetal heart rate may not be necessary in every clinical setting and may not be possible during initiation of neuraxial anesthesia

II Aspiration Prophylaxis

• Oral intake of modest amounts of clear liquids may be allowed for uncomplicated laboring patients

• The uncomplicated patient undergoing elective cesarean delivery may have modest amounts of clear liquids up to 2 h before induction of anesthesia

• The volume of liquid ingested is less important than the presence of particulate matter in the liquid ingested

• Patients with additional risk factors for aspiration (e.g., morbid obesity, diabetes, difficult airway) or patients at increased risk for operative delivery (e.g., nonreassuring fetal heart rate pattern) may have further restrictions of oral intake, determined on a case-by-case basis

• Solid foods should be avoided in laboring patients

• Patients undergoing elective surgery (e.g., scheduled cesarean delivery or postpartum tubal ligation) should undergo a fasting period for solids of 6–8 h depending on the type of food ingested (e.g., fat content)

• Before surgical procedures (i.e., cesarean delivery, postpartum tubal ligation), practitioners should consider timely administration of non-particulate antacids, H2 receptor antagonists, and/or metoclopramide for aspiration prophylaxis

III Anesthetic Care for Labor and Delivery

Neuraxial Techniques: Availability of Resources.

• When neuraxial techniques that include local anesthetics are chosen, appropriate resources for the treatment of complications (e.g., hypotension, systemic toxicity, high spinal anesthesia) should be available

• If an opioid is added, treatments for related complications (e.g., pruritus, nausea, respiratory depression) should be available

• An intravenous infusion should be established before the initiation of neuraxial analgesia or anesthesia and maintained throughout the duration of the neuraxial analgesic or anesthetic

• Administration of a fixed volume of intravenous fluid is not required before neuraxial analgesia is initiated

Timing of Neuraxial Analgesia and Outcome of Labor.

• Neuraxial analgesia should not be withheld on the basis of achieving an arbitrary cervical dilation, and should be offered on an individualized basis when this service is available

• Patients may be reassured that the use of neuraxial analgesia does not increase the incidence of cesarean delivery

Neuraxial Analgesia and Trial of Labor after Previous Cesarean Delivery.

• Neuraxial techniques should be offered to patients attempting vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery

• For these patients, it is also appropriate to consider early placement of a neuraxial catheter that can be used later for labor analgesia or for anesthesia in the event of operative delivery

Early Insertion of Spinal or Epidural Catheter for Complicated Parturients.

• Early insertion of a spinal or epidural catheter for obstetric (e.g., twin gestation or preeclampsia) or anesthetic indications (e.g., anticipated difficult airway or obesity) should be considered to reduce the need for general anesthesia if an emergent procedure becomes necessary

• In these cases, the insertion of a spinal or epidural catheter may precede the onset of labor or a patient's request for labor analgesia

Continuous Infusion Epidural (CIE) Analgesia.

• The selected analgesic/anesthetic technique should reflect patient needs and preferences, practitioner preferences or skills, and available resources

• CIE may be used for effective analgesia for labor and delivery

• When a continuous epidural infusion of local anesthetic is selected, an opioid may be added to reduce the concentration of local anesthetic, improve the quality of analgesia, and minimize motor block

• Adequate analgesia for uncomplicated labor and delivery should be administered with the secondary goal of producing as little motor block as possible by using dilute concentrations of local anesthetics with opioids

• The lowest concentration of local anesthetic infusion that provides adequate maternal analgesia and satisfaction should be administered

Single-injection Spinal Opioids with or without Local Anesthetics.

• Single-injection spinal opioids with or without local anesthetics may be used to provide effective, although time-limited, analgesia for labor when spontaneous vaginal delivery is anticipated

• If labor is expected to last longer than the analgesic effects of the spinal drugs chosen or if there is a good possibility of operative delivery, a catheter technique instead of a single injection technique should be considered

• A local anesthetic may be added to a spinal opioid to increase duration and improve quality of analgesia

Pencil-point Spinal Needles.

• Pencil-point spinal needles should be used instead of cutting-bevel spinal needles to minimize the risk of post–dural puncture headache

Patient-controlled Epidural Analgesia (PCEA).

• PCEA may be used to provide an effective and flexible approach for the maintenance of labor analgesia

• PCEA may be preferable to CIE for providing fewer anesthetic interventions, reduced dosages of local anesthetics, and less motor blockade than fixed-rate continuous epidural infusions

IV Removal of Retained Placenta

• In general, there is no preferred anesthetic technique for removal of retained placenta

• If an epidural catheter is in place and the patient is hemodynamically stable, epidural anesthesia is preferable

• Hemodynamic status should be assessed before administering neuraxial anesthesia

• Aspiration prophylaxis should be considered

• Sedation/analgesia should be titrated carefully due to the potential risks of respiratory depression and pulmonary aspiration during the immediate postpartum period

• In cases involving major maternal hemorrhage, general anesthesia with an endotracheal tube may be preferable to neuraxial anesthesia

• Nitroglycerin may be used as an alternative to terbutaline sulfate or general endotracheal anesthesia with halogenated agents for uterine relaxation during removal of retained placental tissue

• Initiating treatment with incremental doses of intravenous or sublingual (i.e., metered dose spray) nitroglycerin may relax the uterus sufficiently while minimizing potential complications (e.g., hypotension)

V Anesthetic Choices for Cesarean Delivery

• Equipment, facilities, and support personnel available in the labor and delivery operating suite should be comparable to those available in the main operating suite

• Resources for the treatment of potential complications (e.g., failed intubation, inadequate analgesia, hypotension, respiratory depression, pruritus, vomiting) should be available in the labor and delivery operating suite

• Appropriate equipment and personnel should be available to care for obstetric patients recovering from major neuraxial or general anesthesia

• The decision to use a particular anesthetic technique should be individualized based on anesthetic, obstetric, or fetal risk factors (e.g., elective vs. emergency), the preferences of the patient, and the judgment of the anesthesiologist

• Neuraxial techniques are preferred to general anesthesia for most cesarean deliveries

• An indwelling epidural catheter may provide equivalent onset of anesthesia compared with initiation of spinal anesthesia for urgent cesarean delivery

• If spinal anesthesia is chosen, pencil-point spinal needles should be used instead of cutting-bevel spinal needles

• General anesthesia may be the most appropriate choice in some circumstances (e.g., profound fetal bradycardia, ruptured uterus, severe hemorrhage, severe placental abruption)

• Uterine displacement (usually left displacement) should be maintained until delivery regardless of the anesthetic technique used

• Intravenous fluid preloading may be used to reduce the frequency of maternal hypotension after spinal anesthesia for cesarean delivery

• Initiation of spinal anesthesia should not be delayed to administer a fixed volume of intravenous fluid

• Intravenous ephedrine and phenylephrine are both acceptable drugs for treating hypotension during neuraxial anesthesia

• In the absence of maternal bradycardia, phenylephrine may be preferable because of improved fetal acid-base status in uncomplicated pregnancies

• For postoperative analgesia after neuraxial anesthesia for cesarean delivery, neuraxial opioids are preferred over intermittent injections of parenteral opioids

VI Postpartum Tubal Ligation

• For postpartum tubal ligation, the patient should have no oral intake of solid foods within 6-8 h of the surgery, depending on the type of food ingested (e.g., fat content)

• Aspiration prophylaxis should be considered

• Both the timing of the procedure and the decision to use a particular anesthetic technique (i.e., neuraxial vs. general) should be individualized, based on anesthetic risk factors, obstetric risk factors (e.g., blood loss), and patient preferences

• Neuraxial techniques are preferred to general anesthesia for most postpartum tubal ligations

• Be aware that gastric emptying will be delayed in patients who have received opioids during labor and that an epidural catheter placed for labor may be more likely to fail with longer postdelivery time intervals

• If a postpartum tubal ligation is to be performed before the patient is discharged from the hospital, the procedure should not be attempted at a time when it might compromise other aspects of patient care on the labor and delivery unit

VII Management of Obstetric and Anesthetic Emergencies

• Institutions providing obstetric care should have resources available to manage hemorrhagic emergencies

• In an emergency, the use of type-specific or O negative blood is acceptable

• In cases of intractable hemorrhage when banked blood is not available or the patient refuses banked blood, intraoperative cell-salvage should be considered if available

• The decision to perform invasive hemodynamic monitoring should be individualized and based on clinical indications that include the patient's medical history and cardiovascular risk factors

• Labor and delivery units should have personnel and equipment readily available to manage airway emergencies, to include a pulse oximeter and qualitative carbon dioxide detector, consistent with the ASA Practice Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway

• Basic airway management equipment should be immediately available during the provision of neuraxial analgesia

• Portable equipment for difficult airway management should be readily available in the operative area of labor and delivery units

• The anesthesiologist should have a preformulated strategy for intubation of the difficult airway

• When tracheal intubation has failed, ventilation with mask and cricoid pressure, or with a laryngeal mask airway or supraglottic airway device (e.g., Combitube®, Intubating LMA [Fastrach™]) should be considered for maintaining an airway and ventilating the lungs

• If it is not possible to ventilate or awaken the patient, an airway should be created surgically

• Basic and advanced life-support equipment should be immediately available in the operative area of labor and delivery units

• If cardiac arrest occurs during labor and delivery, standard resuscitative measures should be initiated

• Uterine displacement (usually left displacement) should be maintained

• If maternal circulation is not restored within 4 min, cesarean delivery should be performed by the obstetrics team

* Excerpted from Practice Guidelines for Obstetric Anesthesia: An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2007; 106:843-63. ©2007, Americian Society of Anesthesiologists, Inc. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Inc. A copy of the full text can be obtained from American Society of Anesthesiologists, 520 N. Northwest Highway, Park Ridge, IL 60068-2573.

Developed by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia: Joy L. Hawkins, MD (Chair), Denver, Colorado; James F. Arens, MD, Houston, Texas; Brenda A. Bucklin, MD, Denver, Colorado; Richard T. Connis, PhD, Woodinville, Washington; Patricia A. Dailey, MD, Hillsborough, California; David R. Gambling, MBBS, San Diego, California; David G. Nickinovich, PhD, Bellevue, Washington; Linda S. Polley, MD, Ann Arbor, Michigan; Lawrence C. Tsen, MD, Boston, Massachusetts; David J. Wlody, MD, Brooklyn, New York; and Kathryn J. Zuspan, MD, Stillwater, Minnesota.

Submitted for publication October 31, 2006. Accepted for publication October 31, 2006. Supported by the American Society of Anesthesiologists under the direction of James F. Arens, MD, Chair, Committee on Standards and Practice Parameters. Approved by the House of Delegates on October 18, 2006. A list of the references used to develop these Guidelines is available by writing to the American Society of Anesthesiologists.

† International Anesthesia Research Society, 80th Clinical and Scientific Congress, San Francisco, California, March 25, 2006; and Society of Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology 38th Annual Meeting, Hollywood, Florida, April 29, 2006

‡ A prospective nonrandomized controlled trial may be included in a metaanalysis under certain circumstances if specific statistical criteria are met.

§ American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preanesthesia Evaluation: Practice advisory for preanesthesia evaluation. Anesthesiology 2002; 96:485–96.

∥ American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Preoperative Fasting: Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration. Anesthesiology 1999; 90:896–905.

# References to bupivacaine are included for illustrative purposes only, and because bupivacaine is the most extensively studied local anesthetic for continuous infusion epidural analgesia. The Task Force recognizes that other local anesthetics are appropriate for continuous infusion epidural analgesia.

** American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway: Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: An updated report. Anesthesiology 2003; 98:1269–77.

†† 2005 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 2005; 112(suppl):IV1–203.