Ophthalmic Anesthesia

Meenakashi Gupta, Douglas J Rhee

Introduction

The goal of anesthesia is to provide maximal patient comfort while achieving safety for an ophthalmic procedure. In this chapter, the authors will review preoperative considerations, sedation and analgesia, general anesthesia, topical anesthesia, and intraocular and periocular anesthetic techniques. Ocular physiology relevant to ocular anesthesia will also be discussed.

Preoperative Assessment

Ophthalmic surgical patients are frequently elderly and often have numerous health conditions that put their well-being at risk during surgery. The preoperative evaluation plays an important role in screening for comorbidities and helps to lower the risk of preventable adverse intraoperative and postoperative events.1

A complete history and physical examination are the most critical elements of the preoperative evaluation. Particular attention should be given to the assessment of hypertension, pulmonary disease, obesity, diabetes, and risk for or presence of cardiac disease. If general anesthesia is not planned, it is important to assess the patient's ability to lie flat for the duration of the procedure. When evaluating a patient's ability to lie flat, the presence of cardiopulmonary, musculoskeletal disease, and movement disorders should be considered, as well as the existence of factors that may impair communication, such as dementia, language barriers, and hearing deficits.

There is no standard for the recommendation of routine diagnostic tests prior to ophthalmic surgery. One study showed no benefit in routine preoperative testing prior to cataract surgery in patients with no new or worsening medical conditions.2 It is generally accepted that patients over 50 years of age should receive an electrocardiogram and complete blood count with basic electrolytes. However, individual patient factors and institutional policies will vary appropriately. New medical problems and serious, poorly controlled conditions should be normalized prior to surgery.

Ophthalmic surgery is often considered low risk, as most intraocular surgeries have minor physiologic effects on other organ systems and often utilize some form of local or regional anesthesia.

Sedation

Regional nerve block anesthesia is performed for a large percentage of ophthalmic surgeries. Sedation plays an important supplemental role in helping to decrease the discomfort of injection during nerve blockade, limiting patient motion, relieving anxiety, and producing amnesia of the procedure. Sedation/analgesia levels range from minimal sedation (anxiolysis) to moderate sedation (conscious sedation or analgesia) to deep sedation and analgesia.3 Monitored anesthesia care (MAC) is a technique administered by an anesthesiologist that has the potential for a deeper level of sedation. Sedation/analgesia and MAC are generally well tolerated by patients. The most common complications of these techniques are improper levels of sedation, either under- or oversedation, or postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV).

Monitoring the level of sedation is important to prevent patients from progressing into deep sedation with loss of protective airway reflexes. Particular attention is necessary with children, as they may progress rapidly from light to deep levels of sedation. Additionally, patients under ophthalmic regional block may experience inadvertent sedation. The mechanism by which this occurs is unknown. A variety of scales to monitor patients during monitored anesthesia care have been developed, including the Ramsey Sedation Scale,4 the Observer's Assessment of Alertness/Sedation Scale (OAA/S),5 the Neurobehavioral Assessment Scale,6 and the Vancouver Sedative Recovery Scale.7 The University of Michigan Sedation Scale may be used to assess children.8

Distinguishing patient movement and distress resulting from anxiety and that resulting from pain is important. Administering additional sedatives in the setting of pain originating from an inadequate regional block usually worsens the situation, resulting in a deeply sedated, uncooperative patient with uncontrolled movement.

Agents

Sedatives and analgesics are the agents commonly used for sedation. As these agents may have synergistic effects when combined, they should be titrated carefully. Intravenous administration is preferred, though oral or inhalation routes may be necessary in young children. Enteral, subcutaneous, and intramuscular routes should be avoided, given the unpredictable absorption and distribution of drugs through these routes.

Benzodiazepines are the most commonly used agents for perioperative sedation. These drugs bind GABA receptors, inhibiting neuronal transmission. Benzodiazepines provide hypnosis, anxiolysis, amnesia, and lower intraocular pressure (IOP). Excessive doses may result in cardiovascular and respiratory depression, particularly in elderly patients, patients with debilitating disease, and individuals taking opioids concurrently.

Propofol, a modulator of the GABA-A receptor, has been frequently used to achieve amnesia during procedures performed under regional eye blocks. This agent does not provide analgesia and has the potential to cause significant respiratory depression. The agent may also reduce IOP.

Ketamine, a phencyclidine derivative, differs from other sedative-hypnotics as it also has analgesic properties. This agent produces a dissociative state characterized by analgesia with the maintenance of the ability to keep the eyes open, as well as the maintenance of the corneal, cough, and swallow reflexes. Ketamine can also cause pupillary dilation, nystagmus, lacrimation, salivation, and increased skeletal muscle tone, often with coordinated, purposeless movements. Ketamine has minimal effect on the central respiration and cardiovascular systems. The agent is associated with stable or increased IOP and psychic emergence reactions.

Dexmedetomidine is an α2-adrenergic agonist that acts on the locus ceruleus and spinal cord. The agent has a similar cardiorespiratory profile to propofol. However, the onset of action and recovery with this agent has been shown to be longer than that of propofol.9 Use of barbiturates and chloral hydrate, an agent historically used for outpatient pediatric procedures and during cataract surgery in the elderly, has largely been replaced by benzodiazepines.10,11

Opioid analgesic agents may be administered preoperatively to reduce the pain associated with injection and intraoperatively to decrease discomfort associated with light from the operating microscope and surgical manipulation. Fentanyl is the most commonly used opioid supplement to the regional blockade.

General Anesthesia

General anesthesia has a vital role in the care of certain ophthalmic patients. It is the preferred technique for children, mentally delayed individuals, patients with dementia, psychologically unstable patients, patients with claustrophobia, and patients with whom communication is difficult due to language barriers or deafness.

Patients who may have difficulty lying flat or motionless due to musculoskeletal, cardiopulmonary, or neurological diseases, such as Parkinson's disease, may also benefit from this technique. General anesthesia is also preferred for situations where orbital posterior pressure causes increased risk, such as with ruptured globes or preoperative hypotony. General anesthesia may also be used in patients with high myopia in whom perforating injury from regional blocks is a concern. General anesthesia may be useful for long surgeries (2–3 hours) during which patients will likely have difficulty remaining still under local anesthesia for the entire procedure.

The advantages of general anesthesia are minimal risk of retrobulbar and peribulbar hemorrhage, globe perforation, myotoxicity, central spread of local anesthetic with possible brainstem anesthesia, and inadequate intraoperative analgesia. The disadvantages include airway complications and postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV).

The laryngeal mask airway (LMA) provides an alternative to endotracheal intubation that is associated with diminished systemic pressor and oculotensive responses, and a reduced risk of dental damage.12,13 Endotracheal intubation, however, retains an important role in the general anesthesia of patients with an increased risk of gastric regurgitation, such as those with hiatal hernias or a history of recent oral intake, particularly following trauma.

A variety of anesthetic agents may be used safely and effectively during ophthalmic surgery. Propofol is an option for ophthalmic procedures as the agent reduces intraocular pressure and is associated with a low incidence of PONV.14–17 Additionally, use of propofol is advantageous in the ambulatory setting as recovery from the agent is rapid and often associated with a sense of well-being and diminished anxiety.18,19 However, propofol infusion often causes pain due to vein irritation. Lidocaine pretreatment is effective in helping reduce this discomfort.20 Numerous inhalation agents are also available, including isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane. These agents lower IOP in a dose-dependent manner.21,22 Desflurane is associated with the most rapid recovery following surgery. It is important to note that isoflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane have been associated with prolongation of the QTc.23–25

Control of arterial blood pressure during general anesthesia is critical. Significantly elevated blood pressure can damage retinal arterioles and increase the risk of suprachoroidal hemorrhage. In contrast, marked reductions in blood pressure may compromise retinal perfusion, resulting in poor visual outcomes following surgery.

Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) accounts for a major proportion of unanticipated admissions to hospital after intended ambulatory surgery. Straining and increased IOP resulting from PONV can be particularly damaging to the outcomes of ophthalmic surgery. The incidence of PONV is higher in children than in adults.26 PONV is a common side effect following sedation and general anesthesia. The incidence is highest with narcotic-based anesthesia and with volatile agents, and lowest with a total intravenous anesthetic technique using propofol.

Universal PONV prophylaxis has not been shown to be cost-effective; prophylactic treatment should be directed towards patients at increased risk for PONV. Patients are at increased risk for PONV if they have two or more of the following risk factors: female gender, nonsmoking status, history of motion sickness or PONV, and postoperative opioid use.27 Additionally, ophthalmic procedures that cause considerable movement of the eye, such as strabismus surgery, can be associated with postoperative nausea and vomiting. Less stimulating procedures, for example corneal grafting, cataract extraction and trabeculectomy, generally result in fewer instances of PONV.28

The Consensus Guidelines for Managing Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting outlines the following therapy recommendations for PONV.29 Patients at high risk for PONV should be considered for receiving double and triple combinations of antiemetics from different classes, such as serotonic receptor antagonists, steroids, benzamides (droperidol), or phenothiazines. Prophylaxis for children at moderate or high risk for PONV should include a combination of a 5-HT3 antagonist and a second drug from a different category. Antiemetic rescue therapy should be administered to patients who have an emetic episode after surgery. If PONV occurs within 6 hours after surgery in patients who received prophylactic therapy, they should receive a drug from a class different from that of the prophylactic therapy.

Open Globe Injuries

Traditionally, general anesthesia is preferred for patients with open globe injuries as it prevents patient movement and avoids factors that may increase pressure on the open globe. Given the risk for aspiration in trauma cases where there is potential of a history of recent oral intake, rapid-sequence induction is often necessary. The rapid onset and short duration of succinylcholine make it an ideal agent to facilitate endotracheal intubation. However, the use of succinylcholine is highly debated as it can lead to dramatic increases in IOP within minutes.30 The use of succinylcholine is recommended in cases of a difficult airway where the eye is viable.31 To minimize the effects of succinylcholine on IOP, pre-treatment with lidocaine, narcotics, nifedipine, defasciculating doses of nondepolarizing muscle relaxants, or nitroglycerin can be used. Propranolol is also effective, but has significant cardiovascular side effects.32

Regional anesthesia is often considered contraindicated in patients with penetrating eye injuries due to concerns of possible extrusion of intraocular contents during the injection of local anesthetic and the potential for hemorrhage after injection. However, regional anesthesia may be a reasonable alternative to general anesthesia for highly selected patients with open globe injuries. Clinical studies investigating regional anesthesia versus general anesthesia for open globe injuries have noted good visual outcomes and high patient satisfaction in patients who received regional anesthesia for treatment of intraocular foreign bodies, short or anterior wounds, and dehiscence of previous surgical wounds, particularly if patients had better visual acuity and lacked pupillary defects on initial presentation.33–35

The use of topical anesthesia for less severe open globe injuries, those limited to the cornea or the anterior sclera (ocular trauma classification36 zones 1 or 2) has been reported to result in sufficient operative conditions and produce minimal pain and discomfort for patients.37 Topical anesthesia was also successfully used during the repair of an open globe injury in which general anesthesia and regional blocks were contraindicated owing to the presence of cardiopulmonary disease and extensive extrusion of eye contents, respectively.38

Topical Anesthesia

Topical anesthesia was originally discovered by Koller in 1884 when he noted that the application of drops of cocaine solution to eyes led to numbing of the surface of the cornea.39 However, further advances in ophthalmic technology resulted in replacement of topical anesthesia for ophthalmic surgery by general anesthesia and peri- or retrobulbar injection techniques. Recently, topical anesthesia has begun experiencing a growth in popularity through the advent of small-incision phacoemulsification cataract surgery.

Topical treatment anesthetizes the cornea, conjunctiva, and anterior sclera. However, this technique does not provide ocular akinesia, and sensory blockage of the iris and ciliary body may be inadequate. Additionally, topical anesthesia is often very short-acting.

Patient Selection

Topical anesthesia is best reserved for short surgeries and cooperative patients. Patients with minimal anxiety will probably fare best. The patient's response to tonometry and A-scan ultrasonography may indicate how they will tolerate ocular surgery with this technique. Topical anesthesia may be a good choice for monocular patients who require rapid resolution of vision in the operated eye.

Topical anesthesia should be avoided in young patients, as well as patients with a strong blink reflex, nystagmus, difficulty with fixation (due to macular degeneration), and difficulty following commands due to dementia, deafness, or language barriers. Long and difficult surgical cases such as dense cataracts, small pupils, and weak zonules are best managed with another form of anesthesia.

Agents

The most commonly used topical anesthetic agents are proparacaine, tetracaine, lidocaine, and bupivacaine. These esters and amides function by blocking voltage-gated sodium channels. Use of cocaine, one of the first anesthetics in ophthalmic surgery, has been largely curtailed due to its significant central nervous system (CNS) toxicity and high toxicity to the corneal epithelium. Cocaine continues to be used as a surface anesthetic to the upper respiratory tract during select oculoplastic procedures.

The choice of agent may be based on concerns regarding corneal epithelial toxicity, patient comfort, length of the procedure, and the patient's allergy history. High doses or prolonged use of these topical anesthetics are known to be toxic to the corneal epithelium, leading to prolonged wound healing and the formation of corneal erosions.40,41 However, these agents are safe and effective in brief perioperative exposure. Patients with known sensitivities to ester or amides should be given agents from another class. Although proparacaine is an ester anesthetic, it is not metabolized to p-aminobenzoate (PABA), the agent responsible for ester drug reactions, and may be used safely in patients who are allergic to other ester anesthetics. Tetracaine is the most irritating of the agents.

An alternative agent growing in popularity is lidocaine gel. The gel is often used with dilating medications, antibiotics, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and provides good results with both dilation and anesthesia.

Technique

Eyedrops are administered three to four times with applications separated by a few minutes, just before surgery. The patient is instructed to fixate on the microscope light to keep the eye stationary during eyedrop application. Supplemental eyedrops may be provided during the procedure if needed. Alternatively, pieces of sponge saturated with anesthetic may be placed in the superior and inferior fornices. The sponges are removed prior to or following the surgery.

Topical gel may also be applied to the ocular surface shortly prior to surgery. However, lidocaine gel has been found to be a barrier to antisepsis when applied prior to povidone-iodine solution.42 Application of povidone-iodine is recommended prior to lidocaine gel if this method of anesthesia is used.43

Topical anesthesia may be supplemented with sedation, but care should be taken to ensure that patient cooperation is retained.

Efficacy and Complications

Topical anesthetic drops and gel have been used safely and effectively in a wide variety of surgical procedures, including routine and complicated cataract surgeries,44–46 trabeculectomy and glaucoma drainage device implantation,47–50 posterior vitrectomies,51,52 and strabismus surgery.53 Topical anesthesia avoids complications associated with injection into the orbit and results in rapid visual recovery following surgery. Anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy may not need to be discontinued, but ocular and procedural factors may still warrant discontinuation of anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy.

Disadvantages of this technique include patient awareness of the surgical procedure, discomfort with the eyelid speculum and microscope light, pain associated with intraocular manipulation due to inadequate blockade of the iris and ciliary body, and lack of akinesia, including retention of lid movement and reliance on patient cooperation. Additionally, studies comparing topical anesthesia with regional anesthesia during cataract surgery report that patients experience more post-operative discomfort when the procedure is performed using topical anesthesia.54

Intracameral Anesthesia

Intracameral anesthesia, administered through a corneal paracentesis into the anterior chamber, is often used as an adjunct to topical anesthesia. The combination of these techniques allows anesthesia of the cornea, conjunctiva anterior sclera, iris, and ciliary body. Combination topical and intracameral anesthesia has been shown to increase patient cooperation during surgery and reduce patient discomfort during tissue manipulation.55 Patient selection is similar to that for topical anesthesia alone. Additional factors should be assessed when considering the intracameral technique, such as axial length and anticoagulation status.

Technique

Preservative-free lidocaine 1% or preservative-free bupivacaine 0.5% in doses of 0.1–0.5 mL is irrigated into the anterior chamber through a paracentesis or side-port incision. Directing the drug posterior to the iris during injection may provide maximal effect on the iris and ciliary body. After 15–30 seconds, the anesthetic is washed out by irrigation with balanced salt solution or viscoelastic. The ideal timing and placement of intra-cameral anesthesia have not been determined.

Efficacy and Complications

A major concern with the intracameral technique is corneal endothelium and retinal toxicity. Short-term studies suggest that preservative-free 1% lidocaine up to a dose of 0.5 mL is not associated with corneal endothelial toxicity, though higher concentrations are toxic.56–58 The long-term effects of the anesthetic on the corneal endothelium are not known. Intraocular bupivacaine has not been as well studied as lidocaine and the agent may be more toxic to the corneal endothelium than lidocaine. Retinal toxicity is also a concern, as intraocular anesthetics diffuse towards the retina. There have been reports of patients experiencing temporary loss of light perception after intracameral anesthesia.59,60 Numerous in vitro studies suggest lidocaine and bupivacaine may be toxic to the retina. Given these concerns for safety, the American Academy of Ophthalmology suggests that minimal amounts of these anesthetic agents be used and that lidocaine be used preferentially over bupivacaine.61

Intracameral lidocaine has been shown to dilate the pupil well, preempting the need for preoperative dilating drops.62 Combined topical and intracameral anesthesia has been seen as an alternative to retrobulbar anesthesia for phacotrabeculectomy; however, it may be associated with increased patient discomfort.63

Regional Anesthesia

Regional anesthesia is a commonly used technique for ophthalmic surgery. The technique involves the introduction of anesthetic agent into the orbit to provide anesthesia to the cornea, conjunctiva, sclera, intraocular structures, and extraocular muscles. Regional anesthesia may be delivered through a retrobulbar, peribulbar, medial canthal, or sub-Tenon's block.

Agents

The most common choices for regional anesthesia are bupivacaine, lidocaine, ropivacaine, levobupivacaine, articaine, and 2-chloroprocaine. Lidocaine and bupivacaine have been used for many years. Ropivacaine and levobupivacaine, the S-enantiomer of bupivacaine, are long-acting agents with less cardiovascular and central nervous system toxicity than bupivacaine. Articaine and 2-chloroprocaine have a rapid onset and short duration of action, making them good choices for ophthalmic procedures.

Preservative-free anesthetic agents are used in most ophthalmology practices due to concerns for retinal toxicity. Additives may be used to aid in the spread of local anesthetic agents. Hyaluronidase is a proteolytic agent that shortens the time of onset, improves the diffusion and decreases the duration of action of the local anesthetic solution. Side effects of hyaluronidase are rare, but there have been reports of allergic reactions,64 orbital cellulitis,65 and the formation of pseudotumors.66

Epinephrine is used to increase anesthetic duration through vasoconstriction. However, the agent should be used with caution as small amounts of epinephrine may lead to hemodynamic instability in patients with compromised cardiovascular status. Additionally, as the central retinal artery (CRA) is an end-artery, perfusion to the optic nerve may be reduced by CRA constriction. Clonidine has been added to local anesthetics to increase the duration of peribulbar blocks.67 Vecuronium may be added to enhance ocular and eyelid akinesia.68 Clonidine and vecuronium, though, can be harmful due to their significant systemic effects.

General Considerations for Needle-based Blocks

Prior to performing the block, the eye's axial length and the relationship of the eye within the orbit should be assessed to help determine an appropriate angle of the block needle as it enters the orbital space to avoid penetrating the sclera. The axial length may be obtained from measurements made in preparation for cataract surgery or estimated from the patient's eyeglass prescription.

Orbital blocks can be quite painful as the block involves the anesthetic fluid volume infusing rapidly into a tight space filled with delicate structures. Deep sedation is often used in conjunction with the block. However, some practitioners avoid deep sedation during orbital blocks to retain the patient's ability to respond if excessive pain occurs. Excessive pain may indicate injection of anesthetic under the periosteum or into a vital structure, such as an extraocular muscle, the globe, or a nerve. Key elements to help reduce pain when performing regional blocks include: (1) use of fine, short needles (25-gauge, 1 inch); (2) use of anesthetic solution heated to about 35°C; and (3) injection of anesthetic at a slow rate (15–20 s/mL).

Most practitioners use a 23-gauge, 1.5-inch needle. An anatomical study of the orbit with regard to needle length recommends the use of a needle 1.25 in (32 mm) to avoid damage to vulnerable structures.69 Some authors recommend the use of even shorter needles. There is considerable debate regarding the advantages and disadvantages of the sharp and blunt needle bevel.

Retrobulbar Block

The retrobulbar block was first described by Knapp in 1884 when he described the use of topical cocaine to facilitate the injection of local anesthetic behind the eye to block the ciliary nerves.70 This technique in its current form was developed by Atkinson.71 During retrobulbar anesthesia, the needle is directed towards the orbital apex through penetration of the orbital cone, the compartment composed of the four rectus muscles along with the connective tissue septa. The proximity of injection to the nerves and muscles surrounding the orbit results in rapid onset of deep anesthesia with a small volume of anesthetic solution.

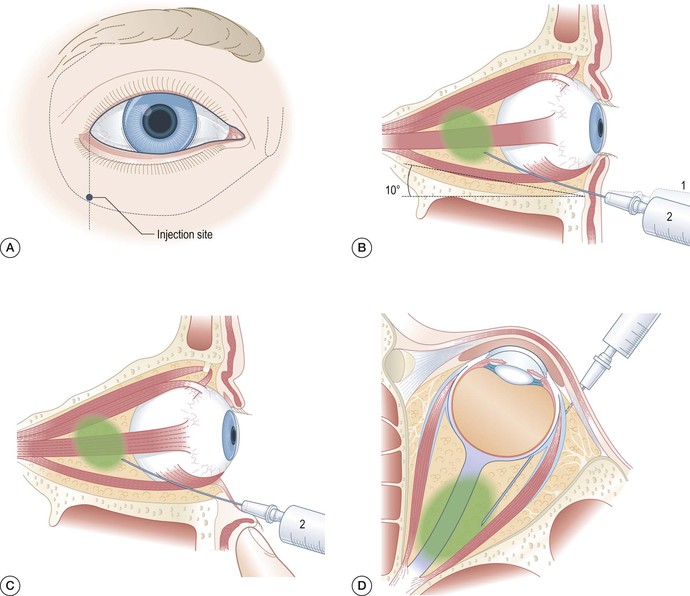

Classical Technique.

The patient should be in the supine position with the eyes in neutral. Some descriptions have suggested that the patient should direct gaze upward and superiorly; however, computed tomography (CT) evidence suggests that this position may lead to greater potential for optic nerve damage as it brings the optic nerve sheath into the path of the needle.72

Topical anesthesia is applied to the eye. To prevent pain on injection, a small wheal of lidocaine local anesthetic is made at the site of the injection, the junction between the middle and outer thirds of the eye just superior to the infraorbital rim. The patient should continue looking straight ahead until the tip of the needle is just behind the equator of the globe. Care should be taken to avoid the globe. If the needle engages the eye, unexpected movement will occur. The needle is then angled upwards and medially to enter the muscle cone behind the eye. If resistance is encountered or blood appears on aspiration, the needle should be withdrawn and reinserted following a period of observation (Fig. 76-1).

Once the needle is within the cone, 3–4 mL of local anesthetic should be injected slowly. With correct placement of the solution, ptosis of the eyelid and slight proptosis of the eye may be observed. These signs must be distinguished from the very rock-hard proptosis and venous engorgement that results from retrobulbar hemorrhage. Following the injection, the eyelids should be closed and a pad placed over them.

To lower intraocular pressure in preparation for surgery, a Honan balloon or other oculopression device can be applied at a pressure of 10 mmHg above the patient's preoperative IOP, or around 30 mmHg for 10 minutes. The eye should be evaluated within 10 minutes for akinesia in all four quadrants. A successful block should result in akinesia and anesthesia in 5 minutes, but the eye will not yet be optimally hypotonic. The retrobulbar technique often leaves the orbicularis oculi fully functional and usually must be done in conjunction with a facial nerve block.

If significant eye movement is present, repetition of the injection may be necessary. Repeated injection is often necessary for patients with large orbits. If there is less movement, a supplemental medial canthal extraconal injection may be given.

Technique Variations.

Fanning describes a variation on the technique in which the insertion point is at the inferotemporal corner where a distinct notch can be felt along the lower orbital rim.73 Insertion of the needle at this point improves the likelihood of entering the intraconal space and potentially reduces injury to the extraocular muscles and the globe. Additionally, the initial angle redirection does not need to change much to enter the intraconal space. This may help reduce the risk of perforation of the globe.

Some prefer an inferior transconjunctival approach to the transcutaneous approach. This method avoids the need for a skin wheal. However, this method may be difficult in patients who are very protective, have short palpebral fissures, or have very deep-set eyes.

Peribulbar Block

The peribulbar block was developed in the late 1970s.74 This block consists of a superior and an inferior injection into the extraconal space. In comparison to the technique used for retrobulbar delivery, the peribulbar needle is applied with less depth, penetrating no deeper than the equator of the globe and with minimal angulation parallel to the globe. The injected anesthetic agent diffuses toward the optic nerve to generate anesthesia. This technique is safer than the retrobulbar technique, as the needle tip is more superficial. The technique is usually associated with minimal discomfort. Peribulbar delivery usually results in effective anesthesia of terminal branches of the facial nerve, eliminating the need for an accompanying facial nerve block. The technique is often recommended in patients with high myopia.

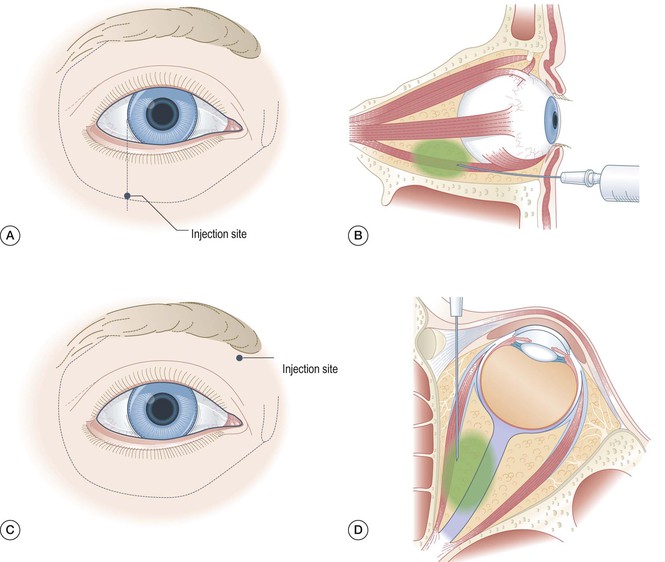

Technique.

Positioning and topical anesthesia for a peribulbar block are similar to those of a retrobulbar block. Small wheals of lidocaine are then placed at (1) the junction of the middle two-thirds and outer one-third of the eye just superior to the infraorbital rim; and (2) just inferior and medial to the supraorbital notch. The inferior injection is performed first. With the patient looking straight ahead, the needle is inserted through the wheal at a right-angle to the skin at the inferior orbital margin and advanced 1.0–2.0 cm along the orbital floor. The needle should be no deeper than the equator of the globe. High resistance may be encountered as the needle passes through the skin and orbital septum. After a test aspiration, 3–4 mL of solution is deposited as the needle is withdrawn into the preseptal space. The volume delivered depends on the size of the orbit and assessment of intraorbital tension (Fig. 76-2).

For the superior injection, the patient's gaze is directed slightly downwards. The injection is made slightly inferior and medial to the supraorbital notch. Remaining parallel to the nose, the needle should enter the skin wheal directed towards the back into the roof of the orbit above the globe to a depth of above 1 cm.

The use of large volumes of local anesthetic solution may result in chemosis and high peribulbar pressures, particularly when the bony orbit is small and in young patients with firm tissues. Immediate akinesia possibly accompanied by vision loss may result. To avoid elevated periocular pressure, waiting a few minutes and applying oculopression before attempting the second injection is recommended, particularly if the orbit becomes tense following the first injection.

If resistance is encountered or blood appears on aspiration, the needle should be withdrawn and reinserted following a period of observation. Following completion of the injections, the eyelids should be closed and a pad placed over them. To lower intraocular pressure in preparation for surgery, a Honan balloon or other oculopression device can be applied at a pressure of 10 mmHg above the patient's preoperative IOP, or around 30 mmHg for 10 minutes. The eye should be evaluated within 10 minutes for akinesia in all four quadrants. A successful block should result in akinesia and anesthesia in 10–15 minutes.

Retroperibulbar Block

The retroperibulbar technique, described by Galindo and Mondshine, is a two-injection block consisting of an inferior retrobulbar and a superior retroperibulbar block.75 This technique results in quick-onset motor blockade through the retrobulbar injection, as well as a long-lasting sensory blockade from the peribulbar component. The peribulbar element of this technique also compensates for the deficiencies of a retrobulbar approach by anesthetizing the commonly missed cranial nerve IV (supplying the superior oblique) and also negates the need for an accessory block of the facial nerve. The block is more than sufficient for routine cataract surgery, but may be useful for delicate surgeries, such as corneal transplant and vitreoretinal surgery. The technique is not recommended for patients with high myopia. The potential for complications of retrobulbar and peribulbar injections is relatively high with this technique.

Technique.

Two injections with two different anesthetic solutions are performed. For the inferior retrobulbar injection, a short-acting agent, such as mepivacaine, is used to produce rapid anesthesia to the motor nerves. A long-acting agent, such as bupivacaine, is used to produce long-lasting sensory anesthesia and blockade with the superior retroperibulbar block. The sites of penetration, inferotemporal and superonasal, are infiltrated with local anesthetic solution, preferably mepivacaine, with a 30-gauge needle. A 25-gauge or 27-gauge, 31 mm Pinpoint needle, which has a pinlike point with a side port, is used for the retrobulbar and retroperibulbar injections. Using a needle with a pinlike point is believed to be less likely to cause penetration of the optic nerve or globe perforation. The needle is bent to an angle of approximately 135°. The angle is introduced to facilitate reangling of the needle so that it follows the roof or floor of the orbit away from the globe to a projected point 4–10 mm behind the globe.

The inferior retrobulbar injection is given first, using 3–4 mL of 2% buffered mepivacaine (pH 7.2) with hyaluronidase. The injection is made at a distance of 4–10 mm behind the eye. The superior retroperibulbar injection is given using a volume of 3–4 mL of 0.5% buffered bupivacaine (pH 7). The solution is injected at the 12 o'clock position. An additional 2–3 mL are injected while withdrawing the needle into the peribulbar space to anesthetize the orbicularis oris and levator palpebrae muscles and the frontal nerve.

Single-injection Peribulbar Block

Whitsett et al.76 and Pannu77 describe single-injection peribulbar techniques. They advocate these techniques for their safety and reduced discomfort for patients. Whitsett's method uses a 26-gauge (7/8)-inch sharp needle to inject 5 mL of an equal-volume mixture of 2% lidocaine and 0.75% bupivacaine with hyaluronidase behind the equator of the eye. An additional 5 mL of anesthetic solution is deposited in the subcutaneous space as the needle is withdrawn. Oculopression follows the injection. This technique results in lid and globe akinesia and ocular anesthesia similar in quality to a retrobulbar block and accessory facial nerve block. Pannu's technique uses an inferotemporal approach to inject 4–5 mL of 1–2% lidocaine with adrenaline and hyaluronidase using a 25-gauge or 27-gauge needle into the peribulbar space just posterior to the equator of the globe. Small volumes of short-acting agents are used to ensure short duration of the anesthesia.

As the single-injection techniques are administered outside the muscle cone, the potential for optic nerve and nervous system complications is decreased. Albeit adequate for routine cataract surgery, the sensory blockade from a single-injection peribulbar block may not be as deep or complete as that produced when a second injection into the superior peribulbar compartment is performed. An alternative anesthetic method may be considered for long or painful procedures.

Medial Canthal Extraconal Block

This block described by Hustead et al. places anesthetic into the fat-filled space between the medial rectus and muscle and the medial orbital wall.78 Anesthetic here can flow into the posteromedial aspect of the intraconal space and the posterosuperior extraconal space. The block may be used as a supplemental block, though some use this as a primary block.

Technique.

The needle is inserted into the tunnel between the caruncle and the medial canthus with the needle tip directed at first toward the medial wall. Caution must be used as in this area, the orbital wall known as the lamina papyracea, is extremely thin. If the needle is inserted with excessive force, the tip will enter the ethmoid sinus and the patient will sense anesthetic running down the back of the nose and into the throat. After lightly touching the medial wall, the needle is withdrawn slightly (1 mm) and redirected towards the orbit parallel to the medial wall and the floor. The needle should be aimed straight posteriorly, to remain in the fat-filled avascular space medial to the medial rectus muscle. The use of a needle longer than 1 inch is not recommended as the optic canal may be impacted by forceful insertion. During insertion, the shoulder (hub and shaft joint) of the needle should not go deeper than the plane of the iris and the bevel of the needle should face the orbital wall to prevent the tip of the needle from damaging the wall (Figs 76-3 and 76-4).

The globe may move medially and then return to neutral gaze during insertion of the needle. However, a properly placed needle is usually medial to the globe and will not injure the globe. Following aspiration, 2–5 mL (up to 10 mL if used as a primary block) of anesthetic solution is injected while frequent palpation of the globe is performed to prevent the development of excessive pressure. Orbital compression may be reapplied for another 5–10 minutes.

An alternative to the medial canthal technique as described by Ripart and colleagues also has good results.79,80 This technique enters the sub-Tenon's space through insertion of the needle in front of the caruncle, between the caruncle and the globe.

Complications of Needle-Based Anesthesia.

Bruising occurs with both peribulbar and retrobulbar techniques. The incidence of bruising is increased with steroids and regular aspirin usage. Patients should be reassured that bruising will resolve quickly. Patients are also at risk for complications of the oculocardiac reflex. Retained light perception vision may occur with both the peribulbar and retrobulbar blocks, but is most common with the peribulbar technique.

Penetration of the optic nerve sheath may lead to optic nerve damage, subarachnoid injection, and damage to central vessels of the retina. There is greater potential for this complication to occur during attempted retrobulbar anesthesia. There are reports of optic nerve damage resulting in blindness as a complication of the retrobulbar technique.81,82 Long, sharp needles may be associated with higher risk of this complication. To date, penetration of the optic nerve sheath following attempted peribulbar anesthesia has not been reported.

Direct spread of local anesthetic to the CNS via the subarachnoid space is a potential complication of attempted retrobulbar delivery. The technique results in symptoms ranging from drowsiness, vomiting, and contralateral blindness to respiratory depression, neurological deficit, convulsions, and cardiopulmonary arrest. In one study of patients undergoing retrobulbar anesthesia, the incidence of CNS spread was noted to be 1 in 375.83

Retrobulbar hemorrhage is an ophthalmic emergency during which damage to the ophthalmic artery causes massive hemorrhage leading to engorgement of vessels, proptosis, tight eyelids, and a rise in intraocular pressure. A funduscopic examination is needed to assess pulsations of the central retinal artery. Immediate lateral canthotomy and postponement of surgery are needed to release pressure in the orbit if pulsations are not adequate.84 In less severe cases, pressure may be reduced by digital massage. Surgery may continue if the eyelid is loose and intraocular pressure decreases.

Needle penetration of the globe has been reported in association with both retrobulbar and peribulbar blocks. One study suggests that high myopia, previous scleral buckling procedures, injection by non-ophthalmologists, and poor patient cooperation may predispose to this injury.85

Injection of local anesthetic into a muscle may result in a long-lasting palsy which may take several weeks to resolve. The inferior rectus and superior oblique muscles are the most likely to be damaged. The inferior rectus is most prone to damage during an inferior retrobulbar injection. The superior oblique is most likely to be damaged when a superomedial approach is used during a peribulbar block.

Sub-Tenon's Block

The sub-Tenon's block (also known as episcleral block, parabulbar block and pinpoint anesthesia) provides an alternative to the sharp needle-based blocks for orbital anesthesia. Following dissection into sub-Tenon's space, anesthetic agent is introduced using a blunt cannula. Diffusion of local anesthetic through the space results in anesthesia and akinesia of the globe and eyelids. The blockade of the short ciliary nerves passing through the Tenon's capsule produces analgesia. Akinesia is caused by blockade of motor nerves in the intraconal and extraconal compartments.

The block has been used for cataract surgery, vitreo-retinal surgery,86,87 panretinal photocoagulation,88,89 strabismus surgery,90 trabeculectomy,91 optic nerve sheath fenestration,92 pain management,93 and therapeutic drug delivery.94 An advantage of the sub-Tenon's block is the high safety profile due to the avoidance of the complications of needle-based regional anesthesia. Additionally, the sub-Tenon's block may be used safely with patients on anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents provided that their clotting profiles are therapeutic.95 However, the block may be difficult to perform in patients who have had prior sub-Tenon's blocks in the same quadrant, previous retinal detachment, strabismus surgery, eye trauma, infection of the orbit, or any procedure or condition that causes peribulbar or subconjunctival scarring.

Anatomy.

Tenon's capsule is a thin fascial sheath that surrounds the eyeball, separating it from the orbital fat. The inner surface of the capsule is smooth and shiny. A potential space, the episcleral (sub-Tenon's) space, separates the capsule from the outer surface of the sclera. Fine bands of connective tissue link the fascial sheath to the sclera. Anteriorly, the capsule fuses to the sclera 5 mm posterior to the corneoscleral junction. Posteriorly, the sheath fuses with the meninges around the optic nerve and with the sclera around the exit of the optic nerve. The tendons of all the extrinsic eye muscles penetrate the sheath as they pass posteriorly from their insertion on the globe.

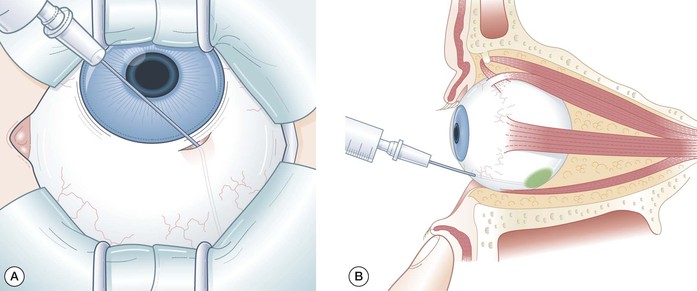

Standard Technique.

The most common approach to the sub-Tenon's space is an inferonasal method described by Stevens.96 Entrance in this quadrant allows for good fluid distribution superiorly, avoids the area of surgery, and reduces the risk of damage to the vortex veins.

Following application of local anesthetic drops, the eye is cleansed with an iodine solution. The eyelids are spread apart with an eyelid speculum or an assistant's fingers. The patient's gaze is directed upward and outwards to expose the inferonasal quadrant. The conjunctiva and Tenon's capsule are gripped with nontoothed forceps 5–10 mm away from the limbus. A small incision is made through the layers, exposing the sclera. A blunt, curved metal sub-Tenon's cannula mounted on a 5 mL syringe filled with anesthetic solution and inserted through the hole along the curvature of the sclera. Local anesthetic is injected slowly and the cannula is removed. Gentle pressure applied to the globe helps spread the anesthetic agent (Fig. 76-5).

Resistance can be encountered during insertion of the cannula due to the intermuscular septum. The application of gentle pressure usually helps advance the cannula. Repositioning or reintroduction of the cannula is advised if hydrodissection is ineffective or if the pressure encountered is too high, as the cannula may be traversing the muscle's Tenon sheath rather than following the globe surface.

Technique Variations.

There are numerous variations of the sub-Tenon's block relating to route of access, type of cannula, local anesthetic agent, volume of anesthetic, and adjuvant used.

Access to the sub-Tenon's space from all quadrants has been described: superotemporal,97 superonasal and inferotemporal,98,99 and medial canthal.80 Comparative data on these methods are lacking. The supranasal route may potentially result in greater complications given the close proximity of vascular, neuronal, and muscular structures. The posterior metal sub-Tenon's cannula is the most commonly used cannula. Although many anesthetic agents have been used for this procedure, lidocaine 2% is frequently used.100 The volume of anesthetic agent to be applied is debated: 3–5 mL is generally used.101 The advantages of adding epinephrine or hyaluronidase to the anesthetic mixture and altering its pH are debated.

Complications.

A number of patients report mild to moderate pain during the sub-Tenon's block that is not significantly relieved by the use of smaller cannulae, premedication, and sedation.102,103 Chemosis may result from anterior injection of anesthetic agent, particularly if a large volume of local anesthetic is injected, the Tenon's capsule is not properly dissected, and shorter cannulae are used.104 Chemosis usually resolves following the application of digital pressure. No intraoperative problems have been reported. However, some surgeons feel that significant chemosis compromises glaucoma surgeries.

Subconjunctival hemorrhage occurrence varies. Hemorrhage can be minimized with careful dissection. No benefit has been shown with the use of disposable diathermy.105 Overspill of anesthetic often occurs. Incomplete dissection of the sub-Tenon's capsule, presence of resistance to injection, and traction during injection can result in overspill. Diathermy use and gentle pressure over the insertion site with a surgical sponge may help reduce anesthetic loss. Despite adequate injection, the superior oblique muscle may remain active in a small number of patients. Patients may also experience retained visual sensations.106

Serious sight- and life-threatening complications have been reported including, short-lived muscle paresis,107 orbital and retrobulbar hemorrhage,108,109 optic neuropathy, afferent papillary and accommodation defects,110,111 diplopia,112 and cardiorespiratory collapse through injection of anesthetic into the subarachnoid space.113

There is a small rise in IOP following sub-Tenon's block.114,115 Use of the Honan balloon helps reduce the increase in intraocular pressure without compromising the efficacy of anesthesia.116 Sub-Tenon's blocks may result in a decrease in pulsatile blood flow and caution should be used in patients with compromised ocular circulation.117

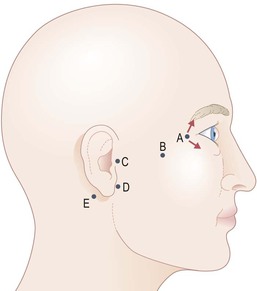

Facial Nerve Blocks

Facial nerve blocks are used to produce inactivity of the orbicularis oculi muscle. Peribulbar injections usually produce paralysis of the orbicularis oculi muscle; however, retrobulbar injections often require a separate block. Several techniques have been described (Fig. 76-6). The closer the block is to the muscle, the fewer undesirable effects on other muscles occur. The most commonly used techniques are the van Lint method and the O'Brien block.

van Lint Method

The van Lint method was first described in 1914.118 The technique blocks the orbicularis oculi muscle at the most distal point of all the described techniques.

As described by van Lint, the technique involves the creation of a small skin wheal at the lateral orbital rim, advancement of the needle and injection of anesthetic 2 cm subcutaneously along the inferior orbital rim, retraction, and then a similar advancement and injection along the superior orbital rim. In total, 2–5 mL of local anesthetic solution are injected. A commonly used variation of the technique uses an insertion point along the inferior orbital rim that is 1 cm more lateral than originally described. This alteration helps reduce lid swelling and blocks more proximal fibers of the nerve.

If additional anesthesia to the orbicularis oculi muscle is needed following a peribulbar block, a fanwise injection can be made to a similar target area from the inferotemporal needle entry point of a peribulbar block.

O'Brien Block

The O'Brien block initially described in 1927 involves insertion of a needle perpendicular to the skin over the condylar process of the mandible, approximately 1 cm anterior to the tragus of the ear.119,120 The position may be verified by assessing for movement when the patient is asked to open his or her mouth. The needle is inserted until contact with periosteum is made and 2–3 mL of local anesthetic solution are injected. Discomfort to the patient may be avoided with a gentle approach of the needle, warmed solution, and slow injection.

Spaeth Block

The Spaeth block is performed by inserting the needle at a site posterior and slightly inferior to the insertion site of the O'Brien block, the posterior margin of the mandibular condyle just below the ear.120 Paresis of most facial muscles on the blocked side usually occurs.

Atkinson Block

The Atkinson block is performed by inserting a needle over the inferior border of the zygoma just lateral to the inferior orbital rim.121 The needle is passed superficial to the zygomatic arch aiming towards a point 1 cm above the tragus of the ear. Five to 10 mL of local anesthetic solution are injected.

Nadbath–Rehman Block

The Nadbath–Rehman block involves insertion of a needle into the hollow immediately anterior to the mastoid process and posterior to the ramus of the mandible, perpendicularly to a depth of approximately 12 mm.122 Approximately 3 mL of anesthetic solution are injected following withdrawal.

This facial nerve block has the greatest potential for complications. Owing to the proximity to the jugular foramen ipsilateral paralysis of CN IX, X, XI may lead to hoarseness, dysphagia, pooling of secretions, agitation, respiratory distress, and laryngospasm. This block results in hemifacial akinesia. Complete hemifacial akinesia interferes with oral intake and is thus not recommended for outpatients.

Ocular Physiology Relevant to Anesthesia

Ophthalmic anesthesia and surgical manipulation may lead to alterations in ocular physiology. Two major areas affected are intraocular pressure and neuro-ophthalmic reflexes.

Intraocular Pressure

Intraocular pressure (IOP) is modulated by three major factors: (1) external pressure on the eye by the contraction of the orbicularis oculi muscle and the tone of the extraocular muscles; (2) venous congestion of orbital veins, as may occur with vomiting and coughing or conditions such as orbital tumor and scleral rigidity; and (3) changes in intraocular contents that are semi-solid (lens, vitreous, or intraocular tumor, or fluid such as blood and aqueous humor). Major control is exerted by the fluid content, particularly the aqueous humor.

Changes in arterial and venous pressures and blood gases may lead to alterations in IOP. The central nervous system is also thought to exert control over IOP. IOP normally ranges from 10 to 21.7 mmHg and is considered abnormal above 22 mmHg. IOP exhibits minor diurnal variation, as well as small fluctuations with each cardiac contraction.

Drugs used in anesthesia, physical interventions by anesthesiologists such as laryngoscopy and intubation, intra- and extraconal anesthesia, oculopression, topical agents such as mydriatics, and miotic agents may produce alterations in IOP. Special care should be taken with patients having baseline elevations in IOP during anesthetic procedures.

Neuro-ophthalmic Reflexes

There are three reflexes particularly associated with anesthesia for ophthalmic surgery: the oculocardiac, oculorespiratory, and oculoemetic reflexes. These reflexes tend to occur most commonly in children, particularly during strabismus surgery.

The oculocardiac reflex was first described in 1908 by Aschner and Dagnini.123,124 This trigeminovagal reflex is characterized by sinus bradycardia and potentially fatal arrhythmias following application of pressure on the globe and traction on the extraocular muscles, conjunctiva, or orbital structures. This effect has been noted during strabismus surgery, vitreoretinal surgery, scleral banding, and tumor surgery, as well as intraconal blocks. The reflex may occur during both local and general anesthesia. Hypercarbia and hypoxemia are believed to increase the incidence and severity of the oculocardiac reflex, as may inappropriate anesthetic depth. Incidence varies between 50% and 80%, according to study population, with a higher incidence in children, probably attributable to a higher vagal tone.

Given the numerous potential complications, prophylactic measures are not usually recommended in adults. Adrenergic drugs have not been shown to be effective.125

Although IV atropine given within 30 minutes of surgery is believed to reduce incidence, IV administration of atropine may yield more serious arrhythmias than the reflex itself. During pediatric strabismus surgery, IV atropine 0.02 mg/kg or 0.01 mg/kg glycopyrrolate can be given before surgery.126 Glycopyrrolate is associated with less tachycardia than atropine.

If arrhythmia occurs, an evaluation of the anesthetic depth and ventilatory status should be attempted. Heart rate and rhythm usually return to baseline within 20 seconds after cessation of surgical manipulation. During repeated manipulation, bradycardia is less likely to recur, probably due to fatigue of the reflex arc at the level of the cardioinhibitory center.127 If serious arrhythmia or reflex recurs, atropine should be administered IV only after manipulation has ceased.

The oculorespiratory reflex is mediated by the trigeminal sensory nucleus and the pneumotaxic center in the pons and the medullary respiratory center.128 The reflex can lead to shallow breathing, slowed respiratory rate or respiratory arrest. This reflex is commonly observed during strabismus surgery. The reflex is often concealed by controlled ventilation. Spontaneously breathing patients should be monitored carefully, as the reflex may lead to hypoxemia, hypercarbia, and arrhythmias. In spontaneously breathing patients, controlled ventilation should be used to contain the reflex. Atropine has not been seen to have any effect on the reflex. The use of controlled ventilation in all children undergoing strabismus surgery has been suggested.129

The oculoemetic reflex is mediated by the trigeminovagal pathway and is thought to be the cause of the high incidence of vomiting associated with strabismus surgery. The reflex is triggered by pulling on the extraocular muscles. The symptoms are treated by local anesthetic injection and antiemetics.