Glomerular Filtration, Renal Blood Flow, and Their Control

Glomerular Filtration—the First Step in Urine Formation

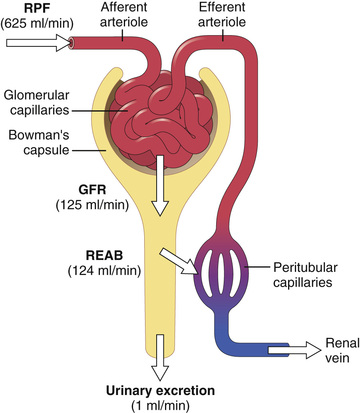

The first step in urine formation is the filtration of large amounts of fluid through the glomerular capillaries into Bowman's capsule—almost 180 liters each day. Most of this filtrate is reabsorbed, leaving only about 1 liter of fluid to be excreted each day, although the renal fluid excretion rate may be highly variable depending on fluid intake. The high rate of glomerular filtration depends on a high rate of kidney blood flow, as well as the special properties of the glomerular capillary membranes. In this chapter we discuss the physical forces that determine the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), as well as the physiological mechanisms that regulate GFR and renal blood flow.

Composition of the Glomerular Filtrate

Like most capillaries, the glomerular capillaries are relatively impermeable to proteins, so the filtered fluid (called the glomerular filtrate) is essentially protein free and devoid of cellular elements, including red blood cells.

The concentrations of other constituents of the glomerular filtrate, including most salts and organic molecules, are similar to the concentrations in the plasma. Exceptions to this generalization include a few low molecular weight substances such as calcium and fatty acids that are not freely filtered because they are partially bound to the plasma proteins. For example, almost one half of the plasma calcium and most of the plasma fatty acids are bound to proteins, and these bound portions are not filtered through the glomerular capillaries.

GFR is About 20 Percent of Renal Plasma Flow

The GFR is determined by (1) the balance of hydrostatic and colloid osmotic forces acting across the capillary membrane and (2) the capillary filtration coefficient (Kf), the product of the permeability and filtering surface area of the capillaries. The glomerular capillaries have a much higher rate of filtration than most other capillaries because of a high glomerular hydrostatic pressure and a large Kf. In the average adult human, the GFR is about 125 ml/min, or 180 L/day. The fraction of the renal plasma flow that is filtered (the filtration fraction) averages about 0.2, which means that about 20 percent of the plasma flowing through the kidney is filtered through the glomerular capillaries (Figure 27-1). The filtration fraction is calculated as follows:

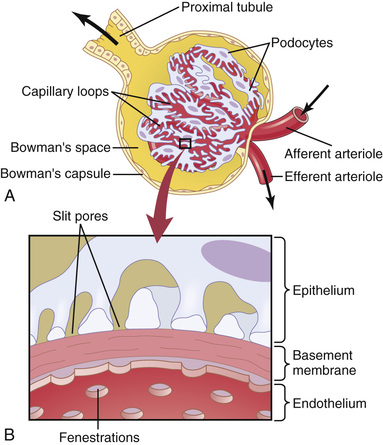

Glomerular Capillary Membrane

The glomerular capillary membrane is similar to that of other capillaries, except that it has three (instead of the usual two) major layers: (1) the endothelium of the capillary, (2) a basement membrane, and (3) a layer of epithelial cells (podocytes) surrounding the outer surface of the capillary basement membrane (Figure 27-2). Together, these layers make up the filtration barrier, which, despite the three layers, filters several hundred times as much water and solutes as the usual capillary membrane. Even with this high rate of filtration, the glomerular capillary membrane normally prevents filtration of plasma proteins.

The high filtration rate across the glomerular capillary membrane is due partly to its special characteristics. The capillary endothelium is perforated by thousands of small holes called fenestrae, similar to the fenestrated capillaries found in the liver, although smaller than the fenestrae of the liver. Although the fenestrations are relatively large, endothelial cell proteins are richly endowed with fixed negative charges that hinder the passage of plasma proteins.

Surrounding the endothelium is the basement membrane, which consists of a meshwork of collagen and proteoglycan fibrillae that have large spaces through which large amounts of water and small solutes can filter. The basement membrane effectively prevents filtration of plasma proteins, in part because of strong negative electrical charges associated with the proteoglycans.

The final part of the glomerular membrane is a layer of epithelial cells that line the outer surface of the glomerulus. These cells are not continuous but have long footlike processes (podocytes) that encircle the outer surface of the capillaries (see Figure 27-2). The foot processes are separated by gaps called slit pores through which the glomerular filtrate moves. The epithelial cells, which also have negative charges, provide additional restriction to filtration of plasma proteins. Thus, all layers of the glomerular capillary wall provide a barrier to filtration of plasma proteins.

Filterability of Solutes Is Inversely Related to Their Size.

The glomerular capillary membrane is thicker than most other capillaries, but it is also much more porous and therefore filters fluid at a high rate. Despite the high filtration rate, the glomerular filtration barrier is selective in determining which molecules will filter, based on their size and electrical charge.

Table 27-1 lists the effect of molecular size on filterability of different molecules. A filterability of 1.0 means that the substance is filtered as freely as water, whereas a filterability of 0.75 means that the substance is filtered only 75 percent as rapidly as water. Note that electrolytes such as sodium and small organic compounds such as glucose are freely filtered. As the molecular weight of the molecule approaches that of albumin, the filterability rapidly decreases, approaching zero.

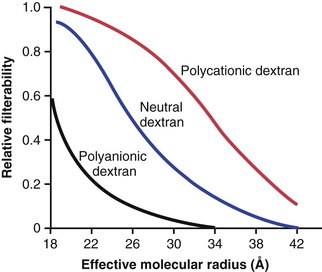

Negatively Charged Large Molecules Are Filtered Less Easily Than Positively Charged Molecules of Equal Molecular Size.

The molecular diameter of the plasma protein albumin is only about 6 nanometers, whereas the pores of the glomerular membrane are thought to be about 8 nanometers (80 angstroms). Albumin is restricted from filtration, however, because of its negative charge and the electrostatic repulsion exerted by negative charges of the glomerular capillary wall proteoglycans.

Figure 27-3 shows how electrical charge affects the filtration of different molecular weight dextrans by the glomerulus. Dextrans are polysaccharides that can be manufactured as neutral molecules or with negative or positive charges. Note that for any given molecular radius, positively charged molecules are filtered much more readily than are negatively charged molecules. Neutral dextrans are also filtered more readily than are negatively charged dextrans of equal molecular weight. The reason for these differences in filterability is that the negative charges of the basement membrane and the podocytes provide an important means for restricting large negatively charged molecules, including the plasma proteins.

In certain kidney diseases, the negative charges on the basement membrane are lost even before there are noticeable changes in kidney histology, a condition referred to as minimal change nephropathy. The cause for this loss of negative charges is still unclear but is believed to be related to an immunological response with abnormal T-cell secretion of cytokines that reduce anions in the glomerular capillary or podocyte proteins. As a result of this loss of negative charges on the basement membranes, some of the lower molecular weight proteins, especially albumin, are filtered and appear in the urine, a condition known as proteinuria or albuminuria. Minimal change nephropathy is most common in young children but can also occur in adults, especially in those who have autoimmune disorders.

Determinants of the GFR

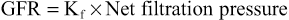

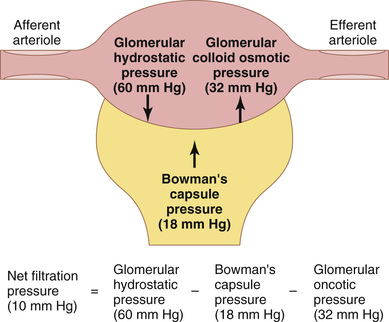

The GFR is determined by (1) the sum of the hydrostatic and colloid osmotic forces across the glomerular membrane, which gives the net filtration pressure, and (2) the glomerular Kf. Expressed mathematically, the GFR equals the product of Kf and the net filtration pressure:

The net filtration pressure represents the sum of the hydrostatic and colloid osmotic forces that either favor or oppose filtration across the glomerular capillaries (Figure 27-4). These forces include (1) hydrostatic pressure inside the glomerular capillaries (glomerular hydrostatic pressure, PG), which promotes filtration; (2) the hydrostatic pressure in Bowman's capsule (PB) outside the capillaries, which opposes filtration; (3) the colloid osmotic pressure of the glomerular capillary plasma proteins (πG), which opposes filtration; and (4) the colloid osmotic pressure of the proteins in Bowman's capsule (πB), which promotes filtration. (Under normal conditions, the concentration of protein in the glomerular filtrate is so low that the colloid osmotic pressure of the Bowman's capsule fluid is considered to be zero.)

The GFR can therefore be expressed as

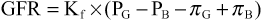

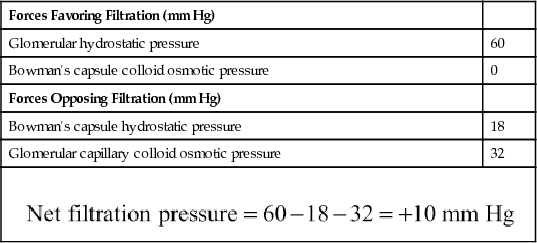

Although the normal values for the determinants of GFR have not been measured directly in humans, they have been estimated in animals such as dogs and rats. Based on the results in animals, the approximate normal forces favoring and opposing glomerular filtration in humans are believed to be as follows (see Figure 27-4):

| Forces Favoring Filtration (mm Hg) | |

| Glomerular hydrostatic pressure | 60 |

| Bowman's capsule colloid osmotic pressure | 0 |

| Forces Opposing Filtration (mm Hg) | |

| Bowman's capsule hydrostatic pressure | 18 |

| Glomerular capillary colloid osmotic pressure | 32 |

| |

Some of these values can change markedly under different physiological conditions, whereas others are altered mainly in disease states, as discussed later.

Increased Glomerular Capillary Filtration Coefficient Increases GFR

The Kf is a measure of the product of the hydraulic conductivity and surface area of the glomerular capillaries. The Kf cannot be measured directly, but it is estimated experimentally by dividing the rate of glomerular filtration by net filtration pressure:

Because the total GFR for both kidneys is about 125 ml/min and the net filtration pressure is 10 mm Hg, the normal Kf is calculated to be about 12.5 ml/min/mm Hg of filtration pressure. When Kf is expressed per 100 grams of kidney weight, it averages about 4.2 ml/min/mm Hg, a value about 400 times as high as the Kf of most other capillary systems of the body; the average Kf of many other tissues in the body is only about 0.01 ml/min/mm Hg per 100 grams. This high Kf for the glomerular capillaries contributes to their rapid rate of fluid filtration.

Although increased Kf raises GFR and decreased Kf reduces GFR, changes in Kf probably do not provide a primary mechanism for the normal day-to-day regulation of GFR. Some diseases, however, lower Kf by reducing the number of functional glomerular capillaries (thereby reducing the surface area for filtration) or by increasing the thickness of the glomerular capillary membrane and reducing its hydraulic conductivity. For example, chronic, uncontrolled hypertension and diabetes mellitus gradually reduce Kf by increasing the thickness of the glomerular capillary basement membrane and, eventually, by damaging the capillaries so severely that there is loss of capillary function.

Increased Bowman's Capsule Hydrostatic Pressure Decreases GFR

Direct measurements, using micropipettes, of hydrostatic pressure in Bowman's capsule and at different points in the proximal tubule in experimental animals suggest that a reasonable estimate for Bowman's capsule pressure in humans is about 18 mm Hg under normal conditions. Increasing the hydrostatic pressure in Bowman's capsule reduces GFR, whereas decreasing this pressure raises GFR. However, changes in Bowman's capsule pressure normally do not serve as a primary means for regulating GFR.

In certain pathological states associated with obstruction of the urinary tract, Bowman's capsule pressure can increase markedly, causing serious reduction of GFR. For example, precipitation of calcium or of uric acid may lead to “stones” that lodge in the urinary tract, often in the ureter, thereby obstructing outflow of the urinary tract and raising Bowman's capsule pressure. This situation reduces GFR and eventually can cause hydronephrosis (distention and dilation of the renal pelvis and calyces) and can damage or even destroy the kidney unless the obstruction is relieved.

Increased Glomerular Capillary Colloid Osmotic Pressure Decreases GFR

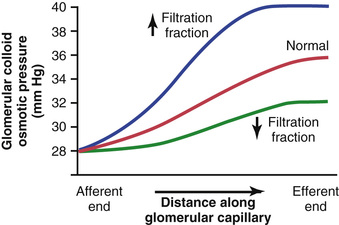

As blood passes from the afferent arteriole through the glomerular capillaries to the efferent arterioles, the plasma protein concentration increases about 20 percent (Figure 27-5). The reason for this increase is that about one fifth of the fluid in the capillaries filters into Bowman's capsule, thereby concentrating the glomerular plasma proteins that are not filtered. Assuming that the normal colloid osmotic pressure of plasma entering the glomerular capillaries is 28 mm Hg, this value usually rises to about 36 mm Hg by the time the blood reaches the efferent end of the capillaries. Therefore, the average colloid osmotic pressure of the glomerular capillary plasma proteins is midway between 28 and 36 mm Hg, or about 32 mm Hg.

Thus, two factors that influence the glomerular capillary colloid osmotic pressure are (1) the arterial plasma colloid osmotic pressure and (2) the fraction of plasma filtered by the glomerular capillaries (filtration fraction). Increasing the arterial plasma colloid osmotic pressure raises the glomerular capillary colloid osmotic pressure, which in turn decreases the GFR.

Increasing the filtration fraction also concentrates the plasma proteins and raises the glomerular colloid osmotic pressure (see Figure 27-5). Because the filtration fraction is defined as GFR/renal plasma flow, the filtration fraction can be increased either by raising the GFR or by reducing renal plasma flow. For example, a reduction in renal plasma flow with no initial change in GFR would tend to increase the filtration fraction, which would raise the glomerular capillary colloid osmotic pressure and tend to reduce the GFR. For this reason, changes in renal blood flow can influence GFR independently of changes in glomerular hydrostatic pressure.

With increasing renal blood flow, a lower fraction of the plasma is initially filtered out of the glomerular capillaries, causing a slower rise in the glomerular capillary colloid osmotic pressure and less inhibitory effect on the GFR. Consequently, even with a constant glomerular hydrostatic pressure, a greater rate of blood flow into the glomerulus tends to increase the GFR and a lower rate of blood flow into the glomerulus tends to decrease the GFR.

Increased Glomerular Capillary Hydrostatic Pressure Increases GFR

The glomerular capillary hydrostatic pressure has been estimated to be about 60 mm Hg under normal conditions. Changes in glomerular hydrostatic pressure serve as the primary means for physiological regulation of GFR. Increases in glomerular hydrostatic pressure raise the GFR, whereas decreases in glomerular hydrostatic pressure reduce the GFR.

Glomerular hydrostatic pressure is determined by three variables, each of which is under physiological control: (1) arterial pressure, (2) afferent arteriolar resistance, and (3) efferent arteriolar resistance.

Increased arterial pressure tends to raise glomerular hydrostatic pressure and, therefore, to increase the GFR. (However, as discussed later, this effect is buffered by autoregulatory mechanisms that maintain a relatively constant glomerular pressure as blood pressure fluctuates.)

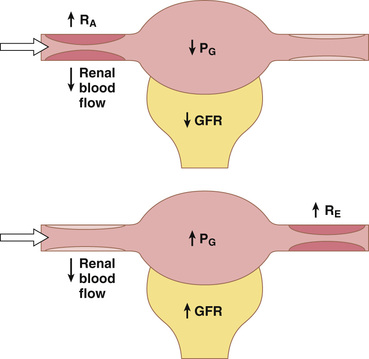

Increased resistance of afferent arterioles reduces glomerular hydrostatic pressure and decreases the GFR (Figure 27-6). Conversely, dilation of the afferent arterioles increases both glomerular hydrostatic pressure and GFR.

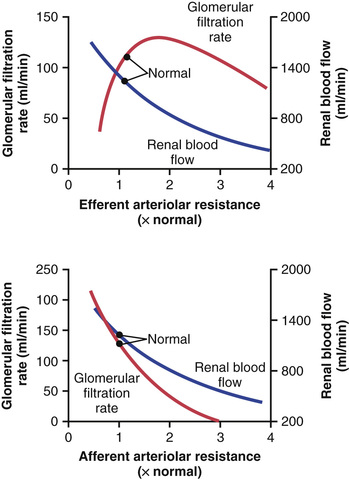

Constriction of the efferent arterioles increases the resistance to outflow from the glomerular capillaries. This mechanism raises glomerular hydrostatic pressure, and as long as the increase in efferent resistance does not reduce renal blood flow too much, GFR increases slightly (see Figure 27-6). However, because efferent arteriolar constriction also reduces renal blood flow, filtration fraction and glomerular colloid osmotic pressure increase as efferent arteriolar resistance increases. Therefore, if constriction of efferent arterioles is severe (more than about a threefold increase in efferent arteriolar resistance), the rise in colloid osmotic pressure exceeds the increase in glomerular capillary hydrostatic pressure caused by efferent arteriolar constriction. When this situation occurs, the net force for filtration actually decreases, causing a reduction in GFR.

Thus, efferent arteriolar constriction has a biphasic effect on GFR (Figure 27-7). At moderate levels of constriction, there is a slight increase in GFR, but with severe constriction, there is a decrease in GFR. The primary cause of the eventual decrease in GFR is as follows: As efferent constriction becomes severe and as plasma protein concentration increases, there is a rapid, nonlinear increase in colloid osmotic pressure caused by the Donnan effect; the higher the protein concentration, the more rapidly the colloid osmotic pressure rises because of the interaction of ions bound to the plasma proteins, which also exert an osmotic effect, as discussed in Chapter 16.

To summarize, constriction of afferent arterioles reduces GFR. However, the effect of efferent arteriolar constriction depends on the severity of the constriction; modest efferent constriction raises GFR, but severe efferent constriction (more than a threefold increase in resistance) tends to reduce GFR.

Table 27-2 summarizes the factors that can decrease GFR.

Table 27-2

Factors That Can Decrease the Glomerular Filtration Rate

| Physical Determinants* | Physiological/Pathophysiological Causes |

| ↓Kf → ↓GFR | Renal disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension |

| ↑PB → ↓GFR | Urinary tract obstruction (e.g., kidney stones) |

| ↑πG → ↓GFR | ↓ Renal blood flow, increased plasma proteins |

| ↓PG → ↓GFR ↓AP → ↓PG | ↓ Arterial pressure (has only a small effect because of autoregulation) |

| ↓RE → ↓PG | ↓ Angiotensin II (drugs that block angiotensin II formation) |

| ↑RA → ↓PG | ↑ Sympathetic activity, vasoconstrictor hormones (e.g., norepinephrine, endothelin) |

Renal Blood Flow

In a 70-kilogram man, the combined blood flow through both kidneys is about 1100 ml/min, or about 22 percent of the cardiac output. Considering that the two kidneys constitute only about 0.4 percent of the total body weight, one can readily see that they receive an extremely high blood flow compared with other organs.

As with other tissues, blood flow supplies the kidneys with nutrients and removes waste products. However, the high flow to the kidneys greatly exceeds this need. The purpose of this additional flow is to supply enough plasma for the high rates of glomerular filtration that are necessary for precise regulation of body fluid volumes and solute concentrations. As might be expected, the mechanisms that regulate renal blood flow are closely linked to the control of GFR and the excretory functions of the kidneys.

Renal Blood Flow and Oxygen Consumption

On a per-gram-weight basis, the kidneys normally consume oxygen at twice the rate of the brain but have almost seven times the blood flow of the brain. Thus, the oxygen delivered to the kidneys far exceeds their metabolic needs, and the arterial-venous extraction of oxygen is relatively low compared with that of most other tissues.

A large fraction of the oxygen consumed by the kidneys is related to the high rate of active sodium reabsorption by the renal tubules. If renal blood flow and GFR are reduced and less sodium is filtered, less sodium is reabsorbed and less oxygen is consumed. Therefore, renal oxygen consumption varies in proportion to renal tubular sodium reabsorption, which in turn is closely related to GFR and the rate of sodium filtered (Figure 27-8). If glomerular filtration completely ceases, renal sodium reabsorption also ceases and oxygen consumption decreases to about one-fourth normal. This residual oxygen consumption reflects the basic metabolic needs of the renal cells.

Determinants of Renal Blood Flow

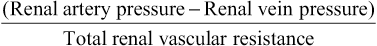

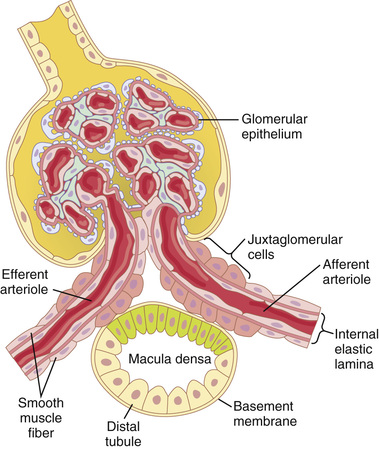

Renal blood flow is determined by the pressure gradient across the renal vasculature (the difference between renal artery and renal vein hydrostatic pressures), divided by the total renal vascular resistance:

Renal artery pressure is about equal to systemic arterial pressure, and renal vein pressure averages about 3 to 4 mm Hg under most conditions. As in other vascular beds, the total vascular resistance through the kidneys is determined by the sum of the resistances in the individual vasculature segments, including the arteries, arterioles, capillaries, and veins (Table 27-3).

Table 27-3

Approximate Pressures and Vascular Resistances in the Circulation of a Normal Kidney

| Vessel | Pressure in Vessel (mm Hg) | Percent of Total Renal Vascular Resistance | |

| Beginning | End | ||

| Renal artery | 100 | 100 | ≈0 |

| Interlobar, arcuate, and interlobular arteries | ≈100 | 85 | ≈16 |

| Afferent arteriole | 85 | 60 | ≈26 |

| Glomerular capillaries | 60 | 59 | ≈1 |

| Efferent arteriole | 59 | 18 | ≈43 |

| Peritubular capillaries | 18 | 8 | ≈10 |

| Interlobar, interlobular, and arcuate veins | 8 | 4 | ≈4 |

| Renal vein | 4 | ≈4 | ≈0 |

Most of the renal vascular resistance resides in three major segments: interlobular arteries, afferent arterioles, and efferent arterioles. Resistance of these vessels is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system, various hormones, and local internal renal control mechanisms, as discussed later. An increase in the resistance of any of the vascular segments of the kidneys tends to reduce the renal blood flow, whereas a decrease in vascular resistance increases renal blood flow if renal artery and renal vein pressures remain constant.

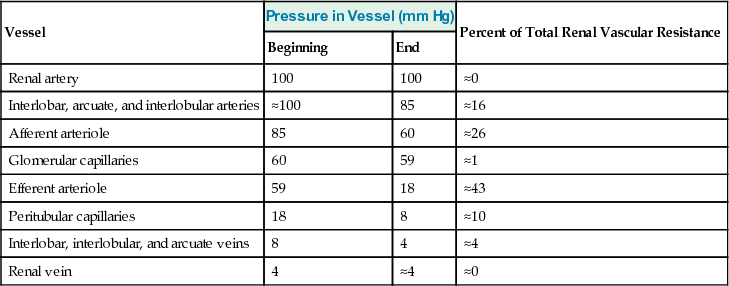

Although changes in arterial pressure have some influence on renal blood flow, the kidneys have effective mechanisms for maintaining renal blood flow and GFR relatively constant over an arterial pressure range between 80 and 170 mm Hg, a process called autoregulation. This capacity for autoregulation occurs through mechanisms that are completely intrinsic to the kidneys, as discussed later in this chapter.

Blood Flow in the Vasa Recta of the Renal Medulla is Very Low Compared with Flow in the Renal Cortex

The outer part of the kidney, the renal cortex, receives most of the kidney's blood flow. Blood flow in the renal medulla accounts for only 1 to 2 percent of the total renal blood flow. Flow to the renal medulla is supplied by a specialized portion of the peritubular capillary system called the vasa recta. These vessels descend into the medulla in parallel with the loops of Henle and then loop back along with the loops of Henle and return to the cortex before emptying into the venous system. As discussed in Chapter 29, the vasa recta play an important role in allowing the kidneys to form concentrated urine.

Physiological Control of Glomerular Filtration and Renal Blood Flow

The determinants of GFR that are most variable and subject to physiological control include the glomerular hydrostatic pressure and the glomerular capillary colloid osmotic pressure. These variables, in turn, are influenced by the sympathetic nervous system, hormones and autacoids (vasoactive substances that are released in the kidneys and act locally), and other feedback controls that are intrinsic to the kidneys.

Strong Sympathetic Nervous System Activation Decreases GFR

Essentially all the blood vessels of the kidneys, including the afferent and the efferent arterioles, are richly innervated by sympathetic nerve fibers. Strong activation of the renal sympathetic nerves can constrict the renal arterioles and decrease renal blood flow and GFR. Moderate or mild sympathetic stimulation has little influence on renal blood flow and GFR. For example, reflex activation of the sympathetic nervous system resulting from moderate decreases in pressure at the carotid sinus baroreceptors or cardiopulmonary receptors has little influence on renal blood flow or GFR. However, as discussed in Chapter 28, even mild increases in renal sympathetic activity can cause decreased sodium and water excretion by increasing renal tubular reabsorption.

The renal sympathetic nerves seem to be most important in reducing GFR during severe, acute disturbances lasting for a few minutes to a few hours, such as those elicited by the defense reaction, brain ischemia, or severe hemorrhage. In the healthy resting person, sympathetic tone appears to have little influence on renal blood flow.

Hormonal and Autacoid Control of Renal Circulation

Several hormones and autacoids can influence GFR and renal blood flow, as summarized in Table 27-4.

Table 27-4

Hormones and Autacoids That Influence GFR

| Hormone or Autacoid | Effect on GFR |

| Norepinephrine | ↓ |

| Epinephrine | ↓ |

| Endothelin | ↓ |

| Angiotensin II | ↔ (prevents ↓) |

| Endothelial-derived nitric oxide | ↑ |

| Prostaglandins | ↑ |

Norepinephrine, Epinephrine, and Endothelin Constrict Renal Blood Vessels and Decrease GFR.

Hormones that constrict afferent and efferent arterioles, causing reductions in GFR and renal blood flow, include norepinephrine and epinephrine released from the adrenal medulla. In general, blood levels of these hormones parallel the activity of the sympathetic nervous system; thus, norepinephrine and epinephrine have little influence on renal hemodynamics except under extreme conditions, such as severe hemorrhage.

Another vasoconstrictor, endothelin, is a peptide that can be released by damaged vascular endothelial cells of the kidneys, as well as by other tissues. The physiological role of this autacoid is not completely understood. However, endothelin may contribute to hemostasis (minimizing blood loss) when a blood vessel is severed, which damages the endothelium and releases this powerful vasoconstrictor. Plasma endothelin levels are also increased in many disease states associated with vascular injury, such as toxemia of pregnancy, acute renal failure, and chronic uremia, and may contribute to renal vasoconstriction and decreased GFR in some of these pathophysiological conditions.

Angiotensin II Preferentially Constricts Efferent Arterioles in Most Physiological Conditions.

A powerful renal vasoconstrictor, angiotensin II, can be considered a circulating hormone and a locally produced autacoid because it is formed in the kidneys and in the systemic circulation. Receptors for angiotensin II are present in virtually all blood vessels of the kidneys. However, the preglomerular blood vessels, especially the afferent arterioles, appear to be relatively protected from angiotensin II–mediated constriction in most physiological conditions associated with activation of the renin-angiotensin system, such as during a low-sodium diet or reduced renal perfusion pressure due to renal artery stenosis. This protection is due to release of vasodilators, especially nitric oxide and prostaglandins, which counteract the vasoconstrictor effects of angiotensin II in these blood vessels.

The efferent arterioles, however, are highly sensitive to angiotensin II. Because angiotensin II preferentially constricts efferent arterioles in most physiological conditions, increased angiotensin II levels raise glomerular hydrostatic pressure while reducing renal blood flow. It should be kept in mind that increased angiotensin II formation usually occurs in circumstances associated with decreased arterial pressure or volume depletion, which tend to decrease GFR. In these circumstances, the increased level of angiotensin II, by constricting efferent arterioles, helps prevent decreases in glomerular hydrostatic pressure and GFR; at the same time, though, the reduction in renal blood flow caused by efferent arteriolar constriction contributes to decreased flow through the peritubular capillaries, which in turn increases reabsorption of sodium and water, as discussed in Chapter 28.

Thus, increased angiotensin II levels that occur with a low-sodium diet or volume depletion help maintain GFR and normal excretion of metabolic waste products such as urea and creatinine that depend on glomerular filtration for their excretion; at the same time, the angiotensin II–induced constriction of efferent arterioles increases tubular reabsorption of sodium and water, which helps restore blood volume and blood pressure. This effect of angiotensin II in helping to “autoregulate” GFR is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

Endothelial-Derived Nitric Oxide Decreases Renal Vascular Resistance and Increases GFR.

An autacoid that decreases renal vascular resistance and is released by the vascular endothelium throughout the body is endothelial-derived nitric oxide. A basal level of nitric oxide production appears to be important for maintaining vasodilation of the kidneys because it allows the kidneys to excrete normal amounts of sodium and water. Therefore, administration of drugs that inhibit formation of nitric oxide increases renal vascular resistance and decreases GFR and urinary sodium excretion, eventually causing high blood pressure. In some hypertensive patients or in patients with atherosclerosis, damage of the vascular endothelium and impaired nitric oxide production may contribute to increased renal vasoconstriction and elevated blood pressure.

Prostaglandins and Bradykinin Decrease Renal Vascular Resistance and Tend to Increase GFR.

Hormones and autacoids that cause vasodilation and increased renal blood flow and GFR include the prostaglandins (PGE2 and PGI2) and bradykinin. These substances are discussed in Chapter 17. Although these vasodilators do not appear to be of major importance in regulating renal blood flow or GFR in normal conditions, they may dampen the renal vasoconstrictor effects of the sympathetic nerves or angiotensin II, especially their effects to constrict the afferent arterioles.

By opposing vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles, the prostaglandins may help prevent excessive reductions in GFR and renal blood flow. Under stressful conditions, such as volume depletion or after surgery, the administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, such as aspirin, that inhibit prostaglandin synthesis may cause significant reductions in GFR.

Autoregulation of GFR and Renal Blood Flow

Feedback mechanisms intrinsic to the kidneys normally keep the renal blood flow and GFR relatively constant, despite marked changes in arterial blood pressure. These mechanisms still function in blood-perfused kidneys that have been removed from the body, independent of systemic influences. This relative constancy of GFR and renal blood flow is referred to as autoregulation (Figure 27-9).

The primary function of blood flow autoregulation in most tissues other than the kidneys is to maintain the delivery of oxygen and nutrients at a normal level and to remove the waste products of metabolism, despite changes in the arterial pressure. In the kidneys, the normal blood flow is much higher than that required for these functions. The major function of autoregulation in the kidneys is to maintain a relatively constant GFR and to allow precise control of renal excretion of water and solutes.

The GFR normally remains autoregulated (that is, it remains relatively constant) despite considerable arterial pressure fluctuations that occur during a person's usual activities. For instance, a decrease in arterial pressure to as low as 70 to 75 mm Hg or an increase to as high as 160 to 180 mm Hg usually changes the GFR less than 10 percent. In general, renal blood flow is autoregulated in parallel with GFR, but GFR is more efficiently autoregulated under certain conditions.

Importance of GFR Autoregulation in Preventing Extreme Changes in Renal Excretion

Although the renal autoregulatory mechanisms are not perfect, they do prevent potentially large changes in GFR and renal excretion of water and solutes that would otherwise occur with changes in blood pressure. One can understand the quantitative importance of autoregulation by considering the relative magnitudes of glomerular filtration, tubular reabsorption, and renal excretion and the changes in renal excretion that would occur without autoregulatory mechanisms.

Normally, GFR is about 180 L/day and tubular reabsorption is 178.5 L/day, leaving 1.5 L/day of fluid to be excreted in the urine. In the absence of autoregulation, a relatively small increase in blood pressure (from 100 to 125 mm Hg) would cause a similar 25 percent increase in GFR (from about 180 to 225 L/day). If tubular reabsorption remained constant at 178.5 L/day, the urine flow would increase to 46.5 L/day (the difference between GFR and tubular reabsorption)—a total increase in urine of more than 30-fold. Because the total plasma volume is only about 3 liters, such a change would quickly deplete the blood volume.

In reality, changes in arterial pressure usually exert much less of an effect on urine volume for two reasons: (1) renal autoregulation prevents large changes in GFR that would otherwise occur, and (2) there are additional adaptive mechanisms in the renal tubules that cause them to increase their reabsorption rate when GFR rises, a phenomenon referred to as glomerulotubular balance (discussed in Chapter 28). Even with these special control mechanisms, changes in arterial pressure still have significant effects on renal excretion of water and sodium; this is referred to as pressure diuresis or pressure natriuresis, and it is crucial in the regulation of body fluid volumes and arterial pressure, as discussed in Chapters 19 and 30.

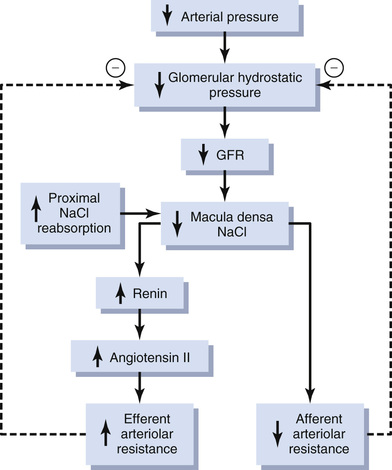

Tubuloglomerular Feedback and Autoregulation of GFR

The kidneys have a special feedback mechanism that links changes in sodium chloride concentration at the macula densa with the control of renal arteriolar resistance and autoregulation of GFR. This feedback helps ensure a relatively constant delivery of sodium chloride to the distal tubule and helps prevent spurious fluctuations in renal excretion that would otherwise occur. In many circumstances, this feedback autoregulates renal blood flow and GFR in parallel. However, because this mechanism is specifically directed toward stabilizing sodium chloride delivery to the distal tubule, instances occur when GFR is autoregulated at the expense of changes in renal blood flow, as discussed later. In other instances, this mechanism may actually cause changes in GFR in response to primary changes in renal tubular sodium chloride reabsorption.

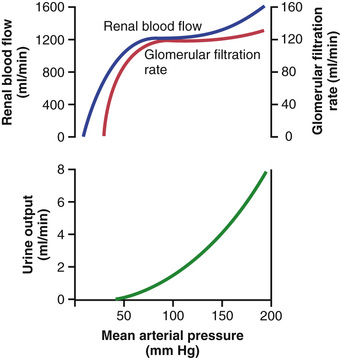

The tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism has two components that act together to control GFR: (1) an afferent arteriolar feedback mechanism and (2) an efferent arteriolar feedback mechanism. These feedback mechanisms depend on special anatomical arrangements of the juxtaglomerular complex (Figure 27-10).

The juxtaglomerular complex consists of macula densa cells in the initial portion of the distal tubule and juxtaglomerular cells in the walls of the afferent and efferent arterioles. The macula densa is a specialized group of epithelial cells in the distal tubules that comes in close contact with the afferent and efferent arterioles. The macula densa cells contain Golgi apparatus, which are intracellular secretory organelles directed toward the arterioles, suggesting that these cells may be secreting a substance toward the arterioles.

Decreased Macula Densa Sodium Chloride Causes Dilation of Afferent Arterioles and Increased Renin Release.

The macula densa cells sense changes in volume delivery to the distal tubule by way of signals that are not completely understood. Experimental studies suggest that a decreased GFR slows the flow rate in the loop of Henle, causing increased reabsorption of the percentage of sodium and chloride ions delivered to the ascending loop of Henle, thereby reducing the concentration of sodium chloride at the macula densa cells. This decrease in sodium chloride concentration initiates a signal from the macula densa that has two effects (Figure 27-11): (1) It decreases resistance to blood flow in the afferent arterioles, which raises glomerular hydrostatic pressure and helps return GFR toward normal, and (2) it increases renin release from the juxtaglomerular cells of the afferent and efferent arterioles, which are the major storage sites for renin. Renin released from these cells then functions as an enzyme to increase the formation of angiotensin I, which is converted to angiotensin II. Finally, the angiotensin II constricts the efferent arterioles, thereby increasing glomerular hydrostatic pressure and helping to return GFR toward normal.

These two components of the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism, operating together by way of the special anatomical structure of the juxtaglomerular apparatus, provide feedback signals to both the afferent and the efferent arterioles for efficient autoregulation of GFR during changes in arterial pressure. When both of these mechanisms are functioning together, the GFR changes only a few percentage points, even with large fluctuations in arterial pressure between the limits of 75 and 160 mm Hg.

Blockade of Angiotensin II Formation Further Reduces GFR During Renal Hypoperfusion.

Blockade of Angiotensin II Formation Further Reduces GFR During Renal Hypoperfusion.

![]() As discussed earlier, a preferential constrictor action of angiotensin II on efferent arterioles helps prevent serious reductions in glomerular hydrostatic pressure and GFR when renal perfusion pressure falls below normal. Administration of drugs that block the formation of angiotensin II (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors) or that block the action of angiotensin II (angiotensin II receptor antagonists) may cause greater reductions in GFR than usual when the renal arterial pressure falls below normal. Therefore, an important complication of using these drugs to treat patients who have hypertension because of renal artery stenosis (partial blockage of the renal artery) is a severe decrease in GFR that can, in some cases, cause acute renal failure. Nevertheless, angiotensin II–blocking drugs can be useful therapeutic agents in many patients with hypertension, congestive heart failure, and other conditions, as long as the patients are monitored to ensure that severe decreases in GFR do not occur.

As discussed earlier, a preferential constrictor action of angiotensin II on efferent arterioles helps prevent serious reductions in glomerular hydrostatic pressure and GFR when renal perfusion pressure falls below normal. Administration of drugs that block the formation of angiotensin II (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors) or that block the action of angiotensin II (angiotensin II receptor antagonists) may cause greater reductions in GFR than usual when the renal arterial pressure falls below normal. Therefore, an important complication of using these drugs to treat patients who have hypertension because of renal artery stenosis (partial blockage of the renal artery) is a severe decrease in GFR that can, in some cases, cause acute renal failure. Nevertheless, angiotensin II–blocking drugs can be useful therapeutic agents in many patients with hypertension, congestive heart failure, and other conditions, as long as the patients are monitored to ensure that severe decreases in GFR do not occur. ![]()

Myogenic Autoregulation of Renal Blood Flow and GFR

Another mechanism that contributes to the maintenance of a relatively constant renal blood flow and GFR is the ability of individual blood vessels to resist stretching during increased arterial pressure, a phenomenon referred to as the myogenic mechanism. Studies of individual blood vessels (especially small arterioles) throughout the body have shown that they respond to increased wall tension or wall stretch by contraction of the vascular smooth muscle. Stretch of the vascular wall allows increased movement of calcium ions from the extracellular fluid into the cells, causing them to contract through the mechanisms discussed in Chapter 8. This contraction prevents excessive stretch of the vessel and at the same time, by raising vascular resistance, helps prevent excessive increases in renal blood flow and GFR when arterial pressure increases.

Although the myogenic mechanism probably operates in most arterioles throughout the body, its importance in renal blood flow and GFR autoregulation has been questioned by some physiologists because this pressure-sensitive mechanism has no means of directly detecting changes in renal blood flow or GFR per se. On the other hand, this mechanism may be more important in protecting the kidney from hypertension-induced injury. In response to sudden increases in blood pressure, the myogenic constrictor response in afferent arterioles occurs within seconds and therefore attenuates transmission of increased arterial pressure to the glomerular capillaries.

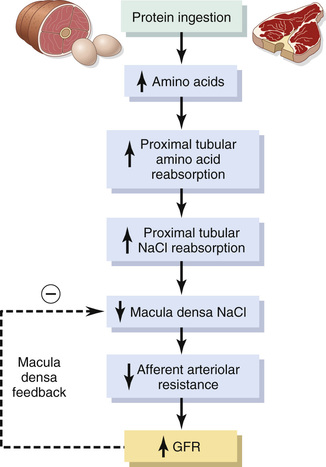

Other Factors That Increase Renal Blood Flow and GFR: High Protein Intake and Increased Blood Glucose.

Other Factors That Increase Renal Blood Flow and GFR: High Protein Intake and Increased Blood Glucose.

![]() Although renal blood flow and GFR are relatively stable under most conditions, there are circumstances in which these variables change significantly. For example, a high protein intake is known to increase both renal blood flow and GFR. With a long-term high-protein diet, such as one that contains large amounts of meat, the increases in GFR and renal blood flow are due partly to growth of the kidneys. However, GFR and renal blood flow also increase 20 to 30 percent within 1 or 2 hours after a person eats a high-protein meal.

Although renal blood flow and GFR are relatively stable under most conditions, there are circumstances in which these variables change significantly. For example, a high protein intake is known to increase both renal blood flow and GFR. With a long-term high-protein diet, such as one that contains large amounts of meat, the increases in GFR and renal blood flow are due partly to growth of the kidneys. However, GFR and renal blood flow also increase 20 to 30 percent within 1 or 2 hours after a person eats a high-protein meal.

One likely explanation for the increased GFR is the following: A high-protein meal increases the release of amino acids into the blood, which are reabsorbed in the proximal tubule. Because amino acids and sodium are reabsorbed together by the proximal tubules, increased amino acid reabsorption also stimulates sodium reabsorption in the proximal tubules. This reabsorption of sodium decreases sodium delivery to the macula densa (see Figure 27-12), which elicits a tubuloglomerular feedback–mediated decrease in resistance of the afferent arterioles, as discussed earlier. The decreased afferent arteriolar resistance then raises renal blood flow and GFR. This increased GFR allows sodium excretion to be maintained at a nearly normal level while increasing the excretion of the waste products of protein metabolism, such as urea.

A similar mechanism may also explain the marked increases in renal blood flow and GFR that occur with large increases in blood glucose levels in persons with uncontrolled diabetes mellitus. Because glucose, like some of the amino acids, is also reabsorbed along with sodium in the proximal tubule, increased glucose delivery to the tubules causes them to reabsorb excess sodium along with glucose. This reabsorption of excess sodium, in turn, decreases the sodium chloride concentration at the macula densa, activating a tubuloglomerular feedback–mediated dilation of the afferent arterioles and subsequent increases in renal blood flow and GFR.

These examples demonstrate that renal blood flow and GFR per se are not the primary variables controlled by the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism. The main purpose of this feedback is to ensure a constant delivery of sodium chloride to the distal tubule, where final processing of the urine takes place. Thus, disturbances that tend to increase reabsorption of sodium chloride at tubular sites before the macula densa tend to elicit increased renal blood flow and GFR, which helps return distal sodium chloride delivery toward normal so that normal rates of sodium and water excretion can be maintained (see Figure 27-12).

An opposite sequence of events occurs when proximal tubular reabsorption is reduced. For example, when the proximal tubules are damaged (which can occur as a result of poisoning by heavy metals, such as mercury, or large doses of drugs, such as tetracyclines), their ability to reabsorb sodium chloride is decreased. As a consequence, large amounts of sodium chloride are delivered to the distal tubule and, without appropriate compensations, would quickly cause excessive volume depletion. One of the important compensatory responses appears to be a tubuloglomerular feedback–mediated renal vasoconstriction that occurs in response to the increased sodium chloride delivery to the macula densa in these circumstances. These examples again demonstrate the importance of this feedback mechanism in ensuring that the distal tubule receives the proper rate of delivery of sodium chloride, other tubular fluid solutes, and tubular fluid volume so that appropriate amounts of these substances are excreted in the urine. ![]()