70

Digestion and Absorption of Carbohydrates

General Principles of Digestion

The major foods on which the body lives (with the exception of small quantities of substances such as vitamins and minerals) can be classified as carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. They generally cannot be absorbed in their natural forms through the gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa and, for this reason, they are useless as nutrients without preliminary digestion.

Digestion is a process that is characterized by a specific sequence of events following the ingestion of foods. These events allow the foods to interact with the various secretions such as enzymes, emulsifying agents, acid, or alkaline substances thereby facilitating the breakdown of complex molecules into simpler molecules under optimum pH. The various events associated with the process of digestion include the following:

1. Mixing and lubricating the food with secretions of the GI tract ensure uniform homogenization.

2. Enzymatic secretion from various glands and cells lining the GI tract breaks down complex molecules into simpler molecules such as oligomers, dimers, and monomers:

a. All digestive enzymes act by hydrolysis.

b. Most GI tract enzymes are secreted as inactive precursors, which are then activated in the GI tract.

3. Secretion of acid or bicarbonate from the GI tract ensures optimal pH for digestion.

4. In the case of fats, secretion of emulsifying agents such as bile acids helps in emulsifying dietary fat thereby promoting fat digestion.

5. Final digestion of most oligomers and dimers occurs at the small intestinal brush border resulting in release of monomers that are finally absorbed.

Therefore, this chapter discusses the processes by which carbohydrates are digested into small enough compounds for absorption and the mechanisms by which the digestive end products, as well as water, electrolytes, and other substances, are absorbed.

Digestion of the Various Foods by Hydrolysis

Hydrolysis of Carbohydrates

Almost all the carbohydrates of the diet are either large polysaccharides or disaccharides, which are combinations of monosaccharides bound to one another by condensation. This phenomenon means that a hydrogen ion (H+) has been removed from one of the monosaccharides, and a hydroxyl ion (OH−) has been removed from the next one. The two monosaccharides then combine with each other at these sites of removal, and the hydrogen and hydroxyl ions combine to form water (H2O).

When carbohydrates are digested, this process is reversed and the carbohydrates are converted into monosaccharides. Specific enzymes in the digestive juices of the GI tract return the hydrogen and hydroxyl ions from water to the polysaccharides and thereby separate the monosaccharides from each other. This process, called hydrolysis, is the following (in which R″–R′ is a disaccharide):

Digestion of Carbohydrates

Carbohydrate Foods of the Diet

Only three major sources of carbohydrates exist in the normal human diet. They are as follows:

1. sucrose, which is the disaccharide known popularly as cane sugar;

2. lactose, which is a disaccharide found in milk;

3. starches, which are large polysaccharides present in almost all nonanimal foods, particularly in potatoes and different types of grains;

4. other carbohydrates ingested to a slight extent, which are amylose, glycogen, alcohol, lactic acid, pyruvic acid, pectins, dextrins, and minor quantities of carbohydrate derivatives in meats.

The diet also contains a large amount of cellulose, which is a carbohydrate. However, no enzymes capable of hydrolyzing cellulose are secreted in the human digestive tract. Consequently, cellulose cannot be considered a food for humans.

Digestion of Carbohydrates Begins in the Mouth and Stomach

When food is chewed, it is mixed with saliva, which contains the digestive enzyme ptyalin (an α-amylase) secreted mainly by the parotid glands. This enzyme hydrolyzes starch into the disaccharide maltose and other small polymers of glucose that contain three to nine glucose molecules, as shown in Figure 70-1. However, the food remains in the mouth only for a short time, so probably not more than 5% of all the starches will have become hydrolyzed by the time the food is swallowed.

Figure 70-1 (A) Digestion of carbohydrates; (B) digestion and absorption of carbohydrates in the GI tract. GI, gastrointestinal. (B) Netter illustration from www.netterimages.com. © Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Starch digestion sometimes continues in the body and fundus of the stomach for as long as 1 hour before the food becomes mixed with the stomach secretions. Activity of the salivary amylase is then blocked by acid of the gastric secretions because the amylase is essentially inactive as an enzyme once the pH of the medium falls below about 4.0. Nevertheless, on average, before food and its accompanying saliva become completely mixed with the gastric secretions, as much as 30–40% of the starches will have been hydrolyzed mainly to form maltose.

Digestion of Carbohydrates in the Small Intestine

Digestion by Pancreatic Amylase

Pancreatic secretion, like saliva, contains a large quantity of α-amylase that is almost identical in its function to the α-amylase of saliva but is several times as powerful. Therefore, within 15–30 minutes after the chyme empties from the stomach into the duodenum and mixes with pancreatic juice, virtually all the carbohydrates will have become digested.

In general, the carbohydrates are almost totally converted into maltose and/or other small glucose polymers before passing beyond the duodenum or upper jejunum.

Hydrolysis of Disaccharides and Small Glucose Polymers into Monosaccharides by Intestinal Epithelial Enzymes

The enterocytes lining the villi of the small intestine contain four enzymes (lactase, sucrase, maltase, and α-dextrinase), which are capable of splitting the disaccharides lactose, sucrose, and maltose, plus other small glucose polymers, into their constituent monosaccharides. These enzymes are located in the enterocytes covering the intestinal microvilli brush border, so the disaccharides are digested as they come in contact with these enterocytes.

Lactose splits into a molecule of galactose and a molecule of glucose. Sucrose splits into a molecule of fructose and a molecule of glucose. Maltose and all other small glucose polymers split into multiple molecules of glucose. Thus, the final products of carbohydrate digestion are all monosaccharides. They are all water soluble and are absorbed immediately into the portal blood (Box 70-1).

The major steps in carbohydrate digestion are summarized in Figure 70-1.

Basic Principles of Gastrointestinal Absorption

It is suggested that the reader review the basic principles of transport of substances through cell membranes discussed in Chapter 4. The following paragraphs present specialized applications of these transport processes during GI absorption.

Anatomical Basis of Absorption

The total quantity of fluid that must be absorbed each day by the intestines is equal to the ingested fluid (about 1.5 L) plus that secreted in the various GI secretions (about 7 L), which comes to a total of 8–9 L. All but about 1.5 L of this fluid is absorbed in the small intestine, leaving only 1.5 L to pass through the ileocecal valve into the colon each day.

The stomach is a poor absorptive area of the GI tract because it lacks the typical villus type of absorptive membrane, and also because the junctions between the epithelial cells are tight junctions. Only a few highly lipid-soluble substances, such as alcohol and some drugs (eg, aspirin), can be absorbed in small quantities.

Folds of Kerckring, Villi, and Microvilli Increase the Mucosal Absorptive Area by Nearly 1000-Fold

Figure 70-2 demonstrates the absorptive surface of the small intestinal mucosa, showing many folds called valvulae conniventes (or folds of Kerckring), which increase the surface area of the absorptive mucosa about threefold.

Figure 70-2 Longitudinal section of the small intestine, showing the valvulae conniventes covered by villi.

Also located on the epithelial surface of the small intestine all the way down to the ileocecal valve are millions of small villi. These villi project about 1 mm from the surface of the mucosa, as shown on the surfaces of the valvulae conniventes in Figure 70-2 and in individual detail in Figure 70-3. The presence of villi on the mucosal surface enhances the total absorptive area another 10-fold.

Figure 70-3 Functional organization of the villus. (A) Longitudinal section; (B) Cross-section showing a basement membrane beneath the epithelial cells and a brush border at the other ends of these cells.

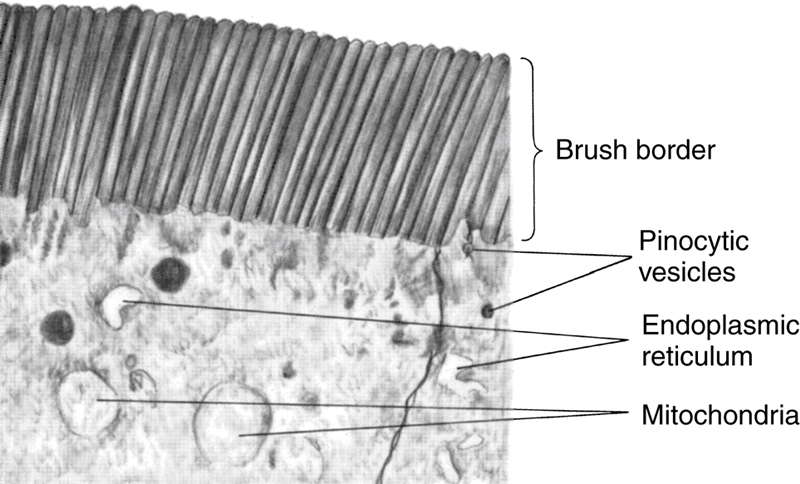

Finally, each intestinal epithelial cell on each villus is characterized by a brush border, consisting of as many as 1000 microvilli that are 1 μm in length and 0.1 μm in diameter and protrude into the intestinal chyme. These microvilli are shown in the electron micrograph in Figure 70-4. This brush border increases the surface area exposed to the intestinal materials at least another 20-fold.

Figure 70-4 Brush border of a gastrointestinal epithelial cell, showing also absorbed pinocytic vesicles, mitochondria, and endoplasmic reticulum lying immediately beneath the brush border. Courtesy Dr. William Lockwood.

Thus, the combination of the folds of Kerckring, the villi, and the microvilli increases the total absorptive area of the mucosa perhaps 1000-fold, making a tremendous total area of 250 or more square meters for the entire small intestine—about the surface area of a tennis court.

Figure 70-3A shows in longitudinal section the general organization of the villus, emphasizing (1) the advantageous arrangement of the vascular system for absorption of fluid and dissolved material into the portal blood and (2) the arrangement of the “central lacteal” lymph vessel for absorption into the lymph. Figure 70-3B shows a cross-section of the villus, and Figure 70-4 shows many small pinocytic vesicles, which are pinched-off portions of infolded enterocyte membrane forming vesicles of absorbed fluids that have been entrapped. Small amounts of substances are absorbed by this physical process of pinocytosis.

Extending from the epithelial cell body into each microvillus of the brush border are multiple actin filaments that contract rhythmically to cause continual movement of the microvilli, keeping them constantly exposed to new quantities of intestinal fluid.

Absorption in the Small Intestine

Absorption from the small intestine each day consists of several hundred grams of carbohydrates, 100 or more grams of fat, 50–100 g of amino acids, 50–100 g of ions, and 7–8 L of water. The absorptive capacity of the normal small intestine is far greater than this; each day as much as several kilograms of carbohydrates, 500 g of fat, 500–700 g of proteins, and 20 or more liters of water can be absorbed. The large intestine can absorb still more water and ions, although it can absorb very few nutrients.

Isosmotic Absorption of Water

Water is transported through the intestinal membrane entirely by diffusion. Furthermore, this diffusion obeys the usual laws of osmosis. Therefore, when the chyme is dilute enough, water is absorbed through the intestinal mucosa into the blood of the villi almost entirely by osmosis.

Conversely, water can also be transported in the opposite direction—from plasma into the chyme. This type of transport occurs especially when hyperosmotic solutions are discharged from the stomach into the duodenum. Within minutes sufficient water usually will be transferred by osmosis to make the chyme isosmotic with the plasma.

Absorption of Ions

Sodium is Actively Transported Through the Intestinal Membrane

Twenty to thirty grams of sodium is secreted in the intestinal secretions each day. In addition, the average person eats 5–8 g of sodium each day. Therefore, to prevent net loss of sodium into the feces, the intestines must absorb 25–35 g of sodium each day, which is equal to about one-seventh of all the sodium present in the body.

Whenever significant amounts of intestinal secretions are lost to the exterior, as in extreme diarrhea, the sodium reserves of the body can sometimes be depleted to lethal levels within hours. Normally, however, less than 0.5% of the intestinal sodium is lost in the feces each day because it is rapidly absorbed through the intestinal mucosa. Sodium also plays an important role in helping to absorb sugars and amino acids, as subsequent discussions reveal.

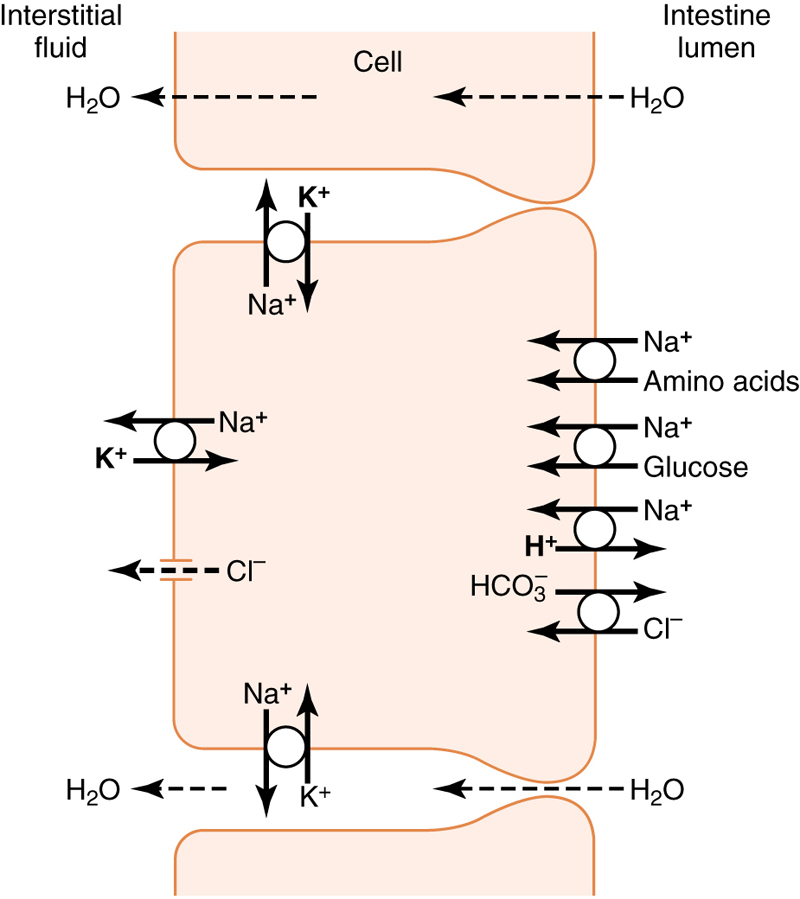

The basic mechanism of sodium absorption from the intestine is shown in Figure 70-5.

Figure 70-5 Absorption of sodium, chloride, glucose, and amino acids through the intestinal epithelium. Note also osmotic absorption of water (ie, water “follows” sodium through the epithelial membrane).

Sodium absorption is powered by active transport of sodium from inside the epithelial cells through the basal and lateral walls of these cells into paracellular spaces. This active transport obeys the usual laws of active transport: It requires energy, and the energy process is catalyzed by appropriate adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase) enzymes in the cell membrane (see Chapter 4). Part of the sodium is absorbed along with chloride ions; in fact, the negatively charged chloride ions are mainly passively “dragged” by the positive electrical charges of the sodium ions.

Active transport of sodium through the basolateral membranes of the cell reduces the sodium concentration inside the cell to a low value (∼50 mEq/L), as shown in Figure 70-5. Because the sodium concentration in the chyme is normally about 142 mEq/L (ie, about equal to that in plasma), sodium moves down this steep electrochemical gradient from the chyme through the brush border of the epithelial cell into the epithelial cell cytoplasm. Sodium is also cotransported through the brush border membrane by several specific carrier proteins, including (1) the sodium–glucose cotransporter, (2) sodium–amino acid cotransporters, and (3) the sodium–hydrogen exchanger.

Osmosis of the Water

The next step in the transport process is osmosis of water by transcellular and paracellular pathways. This osmosis occurs because a large osmotic gradient has been created by the elevated concentration of ions in the paracellular space. Much of this osmosis occurs through the tight junctions between the apical borders of the epithelial cells (the paracellular pathway), but much also occurs through the cells themselves (the transcellular pathway). Osmotic movement of water creates flow of fluid into and through the paracellular spaces and, finally, into the circulating blood of the villus.

Aldosterone Greatly Enhances Sodium Absorption

When a person becomes dehydrated, large amounts of aldosterone are secreted by the cortices of the adrenal glands. Within 1–3 hours this aldosterone causes increased activation of the enzyme and transport mechanisms for all aspects of sodium absorption by the intestinal epithelium. The increased sodium absorption in turn causes secondary increases in absorption of chloride ions, water, and some other substances.

This effect of aldosterone is especially important in the colon because it allows virtually no loss of sodium chloride in the feces and also little water loss. Thus, the function of aldosterone in the intestinal tract is the same as that achieved by aldosterone in the renal tubules, which also serves to conserve sodium chloride and water in the body when a person becomes depleted of sodium chloride and dehydrated.

Absorption of Chloride Ions in the Small Intestine

In the upper part of the small intestine, chloride ion absorption is rapid and occurs mainly by diffusion (ie, absorption of sodium ions through the epithelium creates electronegativity in the chyme and electropositivity in the paracellular spaces between the epithelial cells). Chloride ions then move along this electrical gradient to “follow” the sodium ions. Chloride is also absorbed across the brush border membrane of parts of the ileum and large intestine by a brush border membrane chloride–bicarbonate exchanger. Chloride exits the cell on the basolateral membrane through chloride channels.

Absorption of Bicarbonate Ions in the Duodenum and Jejunum

Often large quantities of bicarbonate ions must be reabsorbed from the upper small intestine because large amounts of bicarbonate ions have been secreted into the duodenum in both pancreatic secretion and bile. The bicarbonate ion is absorbed in an indirect way as follows: When sodium ions are absorbed, moderate amounts of hydrogen ions are secreted into the lumen of the gut in exchange for some of the sodium. These hydrogen ions in turn combine with the bicarbonate ions to form carbonic acid (H2CO3), which then dissociates to form water and carbon dioxide. The water remains as part of the chyme in the intestines, but the carbon dioxide is readily absorbed into the blood and subsequently expired through the lungs. This process is the so-called “active absorption of bicarbonate ions.” It is the same mechanism that occurs in the tubules of the kidneys.

Secretion of Bicarbonate and Absorption of Chloride Ions in the Ileum and Large Intestine

The epithelial cells on the surfaces of the villi in the ileum, as well as on all surfaces of the large intestine, have a special capability of secreting bicarbonate ions in exchange for absorption of chloride ions (see Figure 70-5). This capability is important because it provides alkaline bicarbonate ions that neutralize acid products formed by bacteria in the large intestine.

Active Absorption of Calcium, Iron, Potassium, Magnesium, and Phosphate

Calcium ions are actively absorbed into the blood, especially from the duodenum, and the amount of calcium ion absorption is exactly controlled to supply the daily need of the body for calcium. One important factor controlling calcium absorption is parathyroid hormone secreted by the parathyroid glands and another is vitamin D. Parathyroid hormone activates vitamin D, and the activated vitamin D in turn greatly enhances calcium absorption. These effects are discussed in Chapter 90.

Iron ions are also actively absorbed from the small intestine. The principles of iron absorption and regulation of its absorption in proportion to the body’s need for iron, especially for the formation of hemoglobin, are discussed in Chapter 21.

Potassium, magnesium, phosphate, and probably still other ions can also be actively absorbed through the intestinal mucosa. In general, the monovalent ions are absorbed with ease and in great quantities. Bivalent ions are normally absorbed in only small amounts; for example, maximum absorption of calcium ions is only 1/50 as great as the normal absorption of sodium ions. Fortunately, only small quantities of the bivalent ions are normally required daily by the body.

Absorption of Carbohydrates

Carbohydrates Are Mainly Absorbed as Monosaccharides

Essentially all the carbohydrates in food are absorbed in the form of monosaccharides; only a small fraction is absorbed as disaccharides and almost none is absorbed as larger carbohydrate compounds. By far the most abundant of the absorbed monosaccharides is glucose, which usually accounts for more than 80% of the carbohydrate calories absorbed. The reason for this high percentage is that glucose is the final digestion product of our most abundant carbohydrate food, the starches. The remaining 20% of absorbed monosaccharides is composed almost entirely of galactose and fructose, the galactose derived from milk and the fructose as one of the monosaccharides digested from cane sugar. The steps in carbohydrate digestion and absorption are summarized in Figure 70-1.

Virtually all the monosaccharides are absorbed by a secondary active transport process. We will first discuss the absorption of glucose.

Glucose is Transported by a Sodium Cotransport Mechanism

In the absence of sodium transport through the intestinal membrane, virtually no glucose can be absorbed because glucose absorption occurs in a cotransport mode with active transport of sodium (see Figure 70-5).

The transport of sodium through the intestinal membrane occurs in two stages. First is active transport of sodium ions through the basolateral membranes of the intestinal epithelial cells into the interstitial fluid, thereby depleting sodium inside the epithelial cells. Second, a decrease of sodium inside the cells causes sodium from the intestinal lumen to move through the brush border of the epithelial cells to the cell interiors by a process of secondary active transport.

Thus, the low concentration of sodium inside the cell literally “drags” sodium to the interior of the cell and glucose is dragged along with it. Once inside the epithelial cell, other transport proteins and enzymes cause facilitated diffusion of the glucose through the cell’s basolateral membrane into the paracellular space and from there into the blood.

To summarize, it is the initial active transport of sodium through the basolateral membranes of the intestinal epithelial cells that provides the eventual force for moving glucose through the membranes as well.

Absorption of Other Monosaccharides

Galactose is transported by almost exactly the same mechanism as glucose. Fructose transport does not occur by the sodium cotransport mechanism. Instead, fructose is transported by facilitated diffusion all the way through the intestinal epithelium and is not coupled with sodium transport.

Much of the fructose, on entering the cell, becomes phosphorylated. It is then converted to glucose, and finally transported in the form of glucose the rest of the way into the blood. Because fructose is not cotransported with sodium, its overall rate of transport is only about one-half that of glucose or galactose.