Serial extraction

Definition of serial extraction

Serial extraction is defined as the planned and sequential extraction of certain deciduous teeth followed by removal of specific permanent teeth in order to encourage the spontaneous correction of irregularities.

Historical development

Throughout the history of orthodontics, it has been recognized that the removal of one or more irregular teeth would improve the appearance of the remainder.1 Bunon, in his Essay on Diseases of the Teeth, published in 1743, made the first reference to the removal of deciduous teeth to achieve a better alignment of the permanent teeth.

The names that stand out particularly for the modern development of the serial extraction concept are Kjellgren2 of Sweden, Hotz3, 4 of Switzerland, Heath5, 6 of Australia, and Nance, Lloyd, Dewel and Mayne of the United States.

The word serial extraction was coined by Kjellgren (1929). Nance7 presented clinics on his technique of ‘progressive extraction’ a number of times in the 1940s and has been called the ‘father’ of serial extraction philosophy in the United States. Hotz renamed the technique as ‘guidance of eruption’.

Rationale of serial extraction

1. Growth of jaws: It is in Class I cases that serial extraction finds its most successful application. If there is a Class I malocclusion with generalized crowding in a normally growing child, the clinician would be most unwise to resort to expansion of the maxillary and mandibular arches with fixed or removable appliances. The normal growth of dental, skeletal and soft tissue influences the result of serial extraction.

2. Dentitional adjustment in the anterior segment during first transitional period: The fact that the permanent incisors are larger than the deciduous counterparts is quite obvious, even to the patient. Direct measurement of this incisor liability, as it is termed by Mayne, is possible and recommended. The deciduous–permanent tooth size differential averages 6–7 mm, even when there is no crowding. Any appreciable incisor liability, which would not get adjusted despite the contributions by the adjustment mechanisms listed in Box 31.1 strongly point to a program of guided extraction in the mixed dentition period.

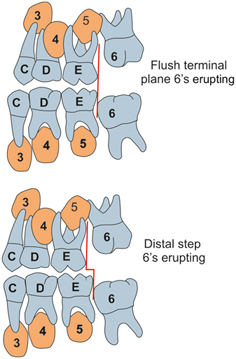

3. Dentitional adjustment in the posterior segment during second transitional period: The combined widths of the mandibular deciduous canine, first molar and second molar averages to 1.7 mm, that is, more than the combined widths of the three permanent successors. As Nance indicated, there is less width differential in the maxillary arch (average width difference 1 mm). This ‘leeway space’ exists on both sides, so it would average 3.4 mm in the mandibular arch and about 2 mm in the maxillary arch.7 Can it be used for incisor crowding? This leeway space is required to correct the flush terminal plane relationship which is a normal, transient developmental phenomenon and is seen in a large percentage of cases (Fig. 31.1).16

When the permanent teeth replaces primary teeth, there is mesial shift of the mandibular first molar utilizing the leeway space and mesiobuccal cusp of the maxillary first molar locks into the mesiobuccal groove of the mandibular first permanent molar. The ‘leeway space’, then, is usually a reserved bit of arch length to allow for the adjustment of maxillary and mandibular dental arches during the critical tooth exchange period.7 When this space is used, holding back the permanent mandibular molars to gain anterior arch length, it may very well have a Class II tendency and result in full Class II division 1 malocclusion. When the settling in the cusps and grooves is prevented, it may create premature contacts that intensify bruxism and functional problems.

4. Dental crowding is the result of inadequate arch size. Serial extraction aims to correct this discrepancy by reducing the tooth material. Why not intercept the developing malocclusion in the early mixed dentition by relieving crowding to provide a chance for nature to adapt with adequate space, instead of waiting for all permanent dentition to emerge into a full-blown malocclusion? The answer is conditionally corroborative. But, before commencing on this ‘robbing Peter to pay Paul’ technique, the orthodontists must question themselves (Fig. 31.2).

5. Physiological tooth movement or drifting occurs at the time and site of extraction. Teeth move both mesially and drift distally. This principle is being utilized in serial extraction for self-correction.

Factors to be considered

The relationship of the mesiodistal diameter of deciduous dentition and permanent dentition is the most important factor to be considered. The other factors are:

Investigations

Clinical examination

When an orthodontist sees a child of 5 or 6 years of age with all the deciduous teeth present in a slightly crowded state or with no spaces between them, it can be predicted with a fair degree of certainty that there will not be enough space in the jaws to accommodate all the permanent teeth in their proper alignment.17 As Dewel, Mayne and others have pointed out, after the eruption of the first permanent molars at 6 years of age, there is probably no increase in the distance from the mesial aspect of the first molar on one side around the arch to the mesial aspect of the first molar on the opposite side.7, 10, 18 If there is any change, it may be an actual reduction of the molar-to-molar arch length, as the ‘leeway space’ is lost through the mesial migration of the first permanent molars during the tooth exchange process and correction of the flush terminal plane relationship (Fig. 31.1).16

Diagnostic discipline

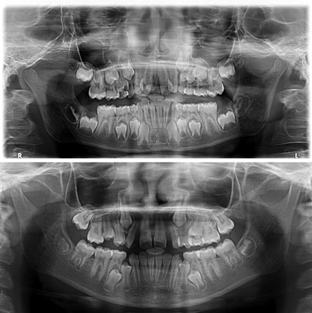

The complete diagnostic records of study models, periapical radiographs, panoramic radiographs and cephalometric radiographs should be made and studied. A calliper or fine line divider is used to measure the combined widths of the teeth present in each segment (Fig. 31.3 ).The circumferential measurement is recorded in study cast from the mesial aspect of the first molar on one side to the mesial aspect of the first molar on the other side (Fig. 31.4).

Indications or clues for serial extraction

The following is a list of possible clinical clues for serial extraction, occurring singly or in combination:

2. Arch length deficiency and tooth size discrepancies

3. Lingual eruption of lateral incisors

4. Unilateral deciduous canine loss and shift to the same side

5. Canines erupting mesially over lateral incisors

6. Mesial drift of buccal segments

7. Abnormal eruption direction and eruption sequence

10. Abnormal resorption (Fig. 31.5)

12. Labial stripping, or gingival recession, usually of a lower incisor.

13. Rotated and tipped permanent molars in either arch are usually a sign of mesial drift of the buccal teeth, and the first molars in particular.

Contraindications of serial extraction

Serial extraction is contraindicated in the following conditions:

Dewel’s technique of serial extraction (CD4 technique)

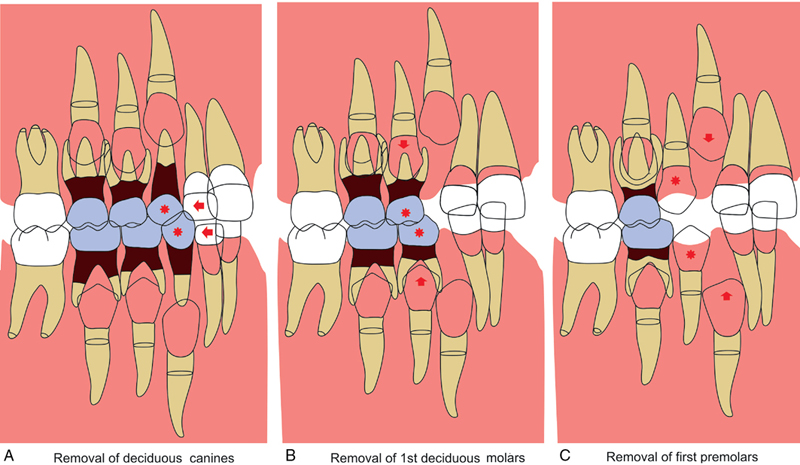

This is usually done in three stages namely (Fig. 31.6): (i) early extraction of deciduous canine, (ii) extraction of deciduous first molars, and (iii) extraction of first premolar. Each stage accomplishes a specific purpose.

Removal of deciduous canines

Purpose of extraction

1. With deciduous canine exfoliation or removal, the immediate purpose is to permit the eruption and optimal alignment of the lateral incisors.

2. Improvement in the position of the central incisors may reasonably be expected.

3. Prevention of the eruption of the maxillary lateral incisors in lingual crossbite or the mandibular incisors in lingual malposition is a primary consideration. But this improvement is gained at the expense of space for the permanent canines.

4. Vitally important is the fact that correct lateral incisor position prevents the mesial migration of the canines into severe malpositions that will require concerted mechanotherapy later.

5. In the maxillary arch, the first premolars erupt uniformly ahead of the canines. In the mandibular arch, it is statistically less predictable. Sometimes, the orthodontist will try to maintain the mandibular deciduous canines somewhat longer hoping to retard the eruption of the permanent canines, while the first premolars take advantage of the edentulous area created by premature removal of the mandibular first deciduous molars. It is desired by most orthodontists embarking on a serial extraction procedure that the first premolars will erupt as soon as possible and ahead of the canines so the premolars may be removed, if necessary. This frequently does not happen (Fig. 31.7). As the experienced clinician knows, there is little evidence that the eruption sequence can be changed, anyway. The too early removal of mandibular deciduous first molars may very well delay the eruption of the first premolars, as a dense layer of bone fills in over them after the deciduous tooth removal. It is important to expedite the normal eruption of the maxillary lateral incisors. Belated eruption and lingual malposition of these teeth permit the maxillary canines to migrate mesially and labially into the space that nature has reserved for the lateral incisors. These ‘high cuspids’, as the orthodontist often calls them, make lingual crossbite of the maxillary lateral incisors more certain, make orthodontic therapy more difficult and practically ensure that the first premolars will ultimately have to be removed. Remember, not all properly managed serial extraction cases inevitably require permanent tooth sacrifice.

Timing of extraction

Generally speaking, these teeth are removed between 8 and 9 years of age in patients with an average developmental pattern.

Removal of the first deciduous molars

Purpose of extraction

1. By this procedure, the orthodontist hopes to accelerate the eruption of the first premolar teeth ahead of the canines, if at all possible.

2. This is particularly ‘touch and go’ in the mandibular arch where the normal sequence so often is for the canine to erupt ahead of the first premolar. The maneuver is seldom successful in the lower arch as has been indicated already.

3. In Class I malocclusions especially, the first premolar may be partially impacted between the permanent canine and the still present second deciduous molar. Hence, the dentist may vary the first procedure of removing all four deciduous canines, as outlined above, and remove the first deciduous molars in the lower arch to tip the eruption scales in the direction of the first premolar.

4. There are times when the orthodontist, while removing first deciduous molars, must consider the possibility of enucleating the unerupted first premolars (usually in the lower arch) to achieve the optimal benefits of the serial extraction procedure. This is a most hazardous step and obviously requires keen diagnostic acumen. Yet in the properly chosen case, the autonomous adjustment and marked improvement in alignment following this step can be most gratifying to both the patient and the orthodontist (Fig. 31.8).

5. Where the canines have erupted prior to the first premolars in the mandibular arch, the convex mesial coronal portion of the second deciduous molar may interfere with first premolar eruption. In such cases, it is necessary to remove the second deciduous molars. No firm rule can be developed here, and each case is judged on its merits with proper diagnostic criteria.

Timing of extraction

Generally speaking, the first deciduous molars are removed approximately 12 months after the deciduous canines. Thus, first deciduous molar removal would be between 9 and 10 years of age in the average developmental pattern.

It would vary from child to child and might sometimes be done earlier in the mandible than in the maxilla, to enhance the early eruption of the first premolars.19, 20

Timing is really not so critical for the removal of the first deciduous molars. There are those who might prefer to remove the remaining deciduous canines and first deciduous molars at the same time, somewhere between 81⁄2 and 10 years of age.

Removal of the erupting first premolars

Word of caution

Before this is done, all diagnostic criteria must again be evaluated. The status of the developing third molars must be determined. It can be a serious mistake to remove four first premolars, only to find that the third molars are congenitally missing and there would have been enough space without premolar removal.

Purpose of extraction

1. If the diagnostic study confirms the inherent arch length deficiency, the purpose of this step is to permit the canine to drop distally into the space created by the extraction. If the procedure has been carried out correctly and the timing has been right, it is a most rewarding experience after the removal of the first premolars to observe the bulging canine eminences move distally on their own into the premolar extraction sites (Fig. 31.9).

2. As indicated previously, sometimes it becomes necessary to remove the mandibular second deciduous molars to permit the first premolars to erupt. This is a more conservative step and is usually preferable to enucleation. But it increases the chances for need of a holding arch to prevent undue loss of space and excessive mesial drift of the first permanent molar (Fig. 31.10).

Timing of extraction

Generally speaking, if the decision has definitely been made that it is necessary to remove the first premolar teeth, the sooner this is done the better the self-adjustment. It serves no purpose to wait for full eruption of the premolar teeth.

Tweed’s technique of serial extraction (D4C technique)

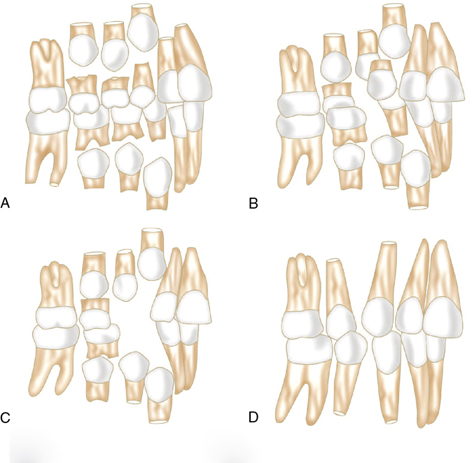

According to Tweed, when discrepancy exists between arch length and tooth material, serial extraction is initiated around 7½ –8½ years of age (Fig. 31.11A to D).

• At approximately 8 years, all deciduous first molars are extracted to hasten the eruption of first premolars.

• Extraction of first premolars and deciduous canines is done simultaneously 4–6 months prior to eruption of permanent canines, when premolars are about the level of alveolar bone crest.

• When the permanent canines erupt they migrate posteriorly into good position.

• Any irregularities in mandibular incisors also get corrected spontaneously by the normal muscular forces.

• The residual space is closed by drifting and tipping of the posterior teeth unless full appliance therapy is implemented.

Disadvantages/problems in serial extraction

1. The timing of tooth removal may be important. It is not always possible to see the patient when we want to or to remove specific teeth at the optimal time for the greatest improvement.

2. The serial extraction patient comes in with better adjustment in the maxillary than in the mandibular arch.

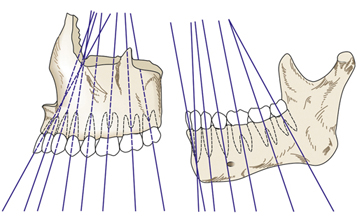

3. Almost always, there is the ‘ditch’ between the permanent canine and the second premolar in the mandibular arch. The roots of the maxillary canine and maxillary second premolar parallel themselves fairly well with autonomous adjustment, whereas this is almost never true in the mandibular arch. The long axes of the teeth converge in the maxillary arch (Fig. 31.12).21 The compensating curve and the occlusal surfaces of the mandibular arch form a concave arc, so the long axes in the mandibular buccal segments diverge. Thus, there is automatic paralleling of the roots with the removal of the first premolar in the maxillary arch. On the contrary, the removal of the mandibular first premolar allows the tipping together of the crowns, accentuating the ‘V’ or ‘ditch’. Seldom does the distance between the apex of the mandibular canine and the apex of the mandibular second premolar decrease on its own. It is necessary for the orthodontist to resort to stringent appliance guidance to close the space and upright the teeth.

4. The ‘bite’ tends to close at least temporarily during the extraction supervision period in most instances, particularly in cases with a Class II tendency.

5. Sometimes there is a further reduction in arch length during the period of guidance. The lower incisors, while aligning themselves, may also become more upright (lingually inclined), which increases the overbite tendency.

6. Occasionally, the removal of premolars does not stimulate the distal migration of canines. Figure 31.13 shows a case in which one maxillary canine remained impacted in a horizontal position. In such instances, the change in treatment plan requires uncovering the canine surgically, placing some sort of guiding appliance and literally pulling the tooth down into normal position.

7. Treatment need to be continued with fixed appliance mechanotherapy as this is not a definitive treatment.

Beforehand, it should be said that there is no single procedure for serial extraction. A provisional diagnostic decision is the best choice. Serial extraction is a long-term guidance program and, therefore, it becomes necessary to re-evaluate and modify provisional decisions many times.