Retention after orthodontic therapy

A great change takes place in the periodontal membrane and contiguous bony structures during tooth movement. “After malposed teeth have been moved into the desired position they must be mechanically supported until all the tissues involved in their support and maintenance in their new positions shall have become thoroughly modified, both in structure and in function, to meet the new requirements” (Angle).1 A phase of retention is normally required after active orthodontic tooth movement. Reitan2 defines retention as holding of teeth in ideal esthetic and functional relation long enough to combat the inherent tendency of the teeth to return to their former positions.

Causes of post-treatment relapse/ need for retention (fig. 43.1)

Stability can be obtained, only if the forces derived from the orofacial soft tissues, periodontal and gingival tissues, occlusion and post-treatment facial growth and development exist in equilibrium. There are different schools of thought with regard to stability of treatment and retention (Box 43.1). The reasons for relapse can be studied under the following headings.3

Forces from the periodontal and gingival tissues

After tooth movement, considerable residual forces remain in the periodontal tissues. It takes over a 3–4 months period after treatment for the reorganization of the periodontal tissues, and over 4–6 months period for remodeling of gingival collagen fiber. The supracrestal elastic fibers remain deviated for more than 232 days. This deviation is most prominent after correction of rotated teeth and space closure where the lower lateral incisors, canines and second premolars tends to migrate towards the original position more commonly than other teeth. Trans-septal fibers continue to exert compressive forces between mandibular contact points possibly contributing to post-treatment crowding.4 Accordingly, over rotation of teeth is advised to ensure correct tooth position after the retention time. Early correction of a rotated tooth prevents relapse of the moved tooth as new fiber bundles, formed in the apical region assists in retaining the rotated teeth. It would also be an advantage to transect stretched fibers around the tooth moved.

Forces from the orofacial soft tissues

It is smart to perform treatment within limits established by soft-tissue environment in particular, the resting pressures of the soft tissues determine final tooth position5 and the ultimate stability of any treatment. Though pressure from lips, cheek or tongue during speaking, swallowing or chewing may be within or above average in related to effective orthodontic tooth movement, the duration of the forces is insufficient to change arch form.

Lower labial segment

The movement of the lower labial segment beyond its narrow zone of labiolingual balance will be unstable unless other factors are changed simultaneously. The lower incisors’ proclination may be stable in a few Class II cases where they had been retroclined by finger sucking habit or by contact with the palate or upper incisors. The existing lower arch form is the best guide in evaluating soft tissue balance and the treatment should be planned for modifying the upper arch around the lower arch.

Arch width

Riedel6 emphasized that mandibular arch form should not be expanded as it compromises stability. Maintenance of the original intercanine width will not assure stability. In fact, a modest amount of intercanine expansion in Class II division 2 cases may be managed more successfully than in Class I and Class II division 1 cases. Expansion of the mandibular intermolar distance also tends to reduce after treatment7, 8 but may be maintained in some instances.

Arch length

Mandibular arch length has been shown to be decreased substantially in both extractions7, 8 and non-extraction cases after retention, in normal untreated occlusions, in generalized spacing and after serial extraction or presurgical proclination.

Overjet

Differential vertical and horizontal growth of the lips occurs in early adolescence, with more growth successful overjet correction seems quite stable where mandibular incremental growth is favorable. Lip growth occurs in early adolescence in boys who has more growth than in girls, possibly endorsing stability. The size of final overjet is related to the lower lip cover only and when it reaches 6 mm. A variety of lip positions may be found in normal range of overjet measurements. Overjet relapse is most likely associated with an increased pretreatment overjet, though associated factors include molar and overbite relapse, premolar and canine relationships, increased interincisal angle, retroclination of formerly proclined lower incisors and soft tissue factors, like persistent tongue thrusting. For the best prospect of overjet stability, a lip seal should be possible.

Occlusal factors and occlusal forces

Angle1 recognized the relevance of occlusal factors to post-treatment stability. Teeth retained by the occlusion are stable, and no retaining appliances are required, e.g. after labial or buccal segment crossbite correction.

The stable reduction of overbite requires a favorable interincisal angle and the lower incisor should be 0–2 mm in front of the upper incisor centroid. A well-interdigitating occlusion prohibits tooth migration and Class I molar relationship may offer stability, though it cannot be assured, as post-treatment growth may significantly change the sagittal molar relationship. Conversely, correction of Class II molar relationship to Class I is beneficial for growth and promotes the stability of the molar correction. Finishing to the gnathologic principles of functional occlusion9 to encourage stability has been emphasized by Roth.

Post-treatment facial growth and development

Facial growth continues throughout adult life; it varies among individuals and is considerable in some cases.10 It has less rate and magnitude than that observed during childhood. The female mandible shows less growth and clockwise rotation and the opposite is seen in males. Therefore, total stability does not exist in craniofacial skeleton or in dentition after orthodontic treatment. The relapse may occur in sagittal, vertical or lateral direction of the skeletal dimensions depending on the post-treatment growth patterns rather than the treatment itself.

The post-treatment occlusion acknowledges to these changes in growth, with dentoalveolar adaptation from the investing soft tissue envelope tending to maintain the occlusal relationships with good intercuspation. Such adaptation is seen itself as lower crowding but this does not occur where there is significant maxillary growth. The evidence implicating third molars is equivocal.

Planning the retention phase

There are six factors3 important in the planning of this phase of ‘treatment’:

2. The original malocclusion and the patient’s growth pattern

3. The type of treatment performed

It is imperative that the patient should be advised before treatment that the retention phase is an essential part of orthodontic treatment design. It should be stressed that serious efforts will be put for a stable result, if such can be achieved and at the same time, if stability is clearly not possible, treatment is best restrained. With practical treatment goals, patient expectations and final satisfaction are likely to be improved.

Original malocclusion and patient’s growth pattern

A retention device should be decided based on the knowledge of the individual patient’s dentofacial structure and the expected direction and magnitude of growth.

Retention following class II correction

Overcorrection of the occlusal relationship as a finishing procedure has been recommended in controlling Class II relapse. The tendency for differential jaw growth resulting in sagittal relapse can be overcome by using headgear in maxillary retainer or functional appliance as retainer. When the initial skeletal problem is severe, the night-time wear of the appliance is usually needed for at least 12–24 months till the growth is reduced to adult levels. Long-term stability by functional appliance therapy depends on favorable post-treatment growth and stable intercuspation.

Retention following class III correction

In early permanent dentition, after correction of mild Class III problems, a functional appliance or a positioner is enough to maintain occlusal relationships but it should be worn till the growth is no longer significant. Chin cup can also be recommended. Refer Box 43.2 for retention plan given by Tweed for different growth trends.

Retention following overbite correction

Maintenance of overbite correction, especially in Class II division 2 malocclusion depends on favorable incisor inclinations in axial direction and the wear of maxillary removable retainer with anterior bite plane for several years. Once stability is achieved, night-time wear is sufficient.

Controlling the eruption of the upper molars is the main key for retention in patients with corrected open bite, but no dependable predictor of post-treatment stability has been invented. Retention by means of high-pull headgear to a maxillary removable retainer or by an open bite activator or bionator should be continued into the late teens. The surgical tongue reduction in certain cases may aid in stability.

Retention following intra-arch correction

As development of lower incisor crowding after retention is the criterion, maintenance of perfect incisor alignment can be guaranteed only by indefinite retention in the lower labial segment.

Permanent retention is required in cases of retention for periodontally aligned teeth, closed space in formerly spaced dentition, and expansion and alignment of arch in cleft palate patients.

Retention of rotated teeth should continue for at least 1 year. But, if relapse is suspected and need to be prevented entirely, it needs prolonged retention.

Types of treatment performed

• After treatment with removable appliance, except in crossbite correction and space maintenance, retention for at least 6 months, i.e. 3 months full-time wear and 3 months night-time wear are recommended.

• After treatment with fixed appliance, especially to align rotated teeth, retention should be at least 12 months, i.e. 3–4 months full-time wear with retainer removed during meals and 8–9 months part-time. Retention then may be stopped, but in growing patients, it should be continued till the growth declines to adult levels.

• After functional appliance therapy or headgear therapy, continuous night-time wear of the appliance is recommended until growth declines to adult levels.

Soft- and hard-tissue adjunctive procedures to enhance stability

Pericision11 or circumferential supracrestal fibrotomy (CSF) reduces rotational relapse by about 30%. It is more successful in the maxillary labial segment than the mandibular. Indirectly, the labiolingual relapse is also lessened and the effect on sulcus depth is minimum. Where attached gingiva is scant, the papilla-dividing procedure is the recommended alternative to CSF.12

Surgical gingivoplasty, designed to minimize the possibility of space reopening in extraction sites after the treatment for space closure, must be used in alliance with proper root positioning of adjacent teeth to achieve maximum success.

Frenectomy, as described by Edwards13 involves apical repositioning of the frenum with denudation of alveolar bone, destruction of the trans-septal fibers and gingivoplasty/recontouring of the labial or palatal gingival papilla in cases of excessive tissue accumulation. It has been shown to drastically reduce the upper midline space re-opening tendency.

Interproximal stripping to create a mesiodistal or buccolingual ratio no greater than 0.72 and 0.95 for lower central incisors and lateral incisors respectively has been suggested for enhancing stability, but this ratio has not been proved to be a vital determinant of lower incisor crowding.

On the basis of data studied up to 10 years post-treatment, CSF and reproximation supplemented with overcorrection and selective root torque have improved the post-treatment stability of lower labial segment while eradicating the necessity for lower retention.

Types of retainer

The different types of retainer, i.e. active, passive, fixed and removable retainers, have been elaborated. After used initially for finishing, a positioner may also be used as a retainer, but it is less efficient in retention of rotated incisors and irregularities than a Hawley retainer.

• Functional appliance may be used for the management of Class II or Class III relapse tendencies.

• Incisors that are becoming irregular may be realigned with a Barrer14 appliance (often in conjunction with interproximal stripping) or a modification thereof.

• Minor tooth movement can be performed through the modified full coverage polycarbonate retainers or clear sectional polyester retainers (Essix retainers) and then the retention appliance may be worn passively.

• Fixed retainer is used to maintain median diastema closure, extraction space in adults, pontic space or after correction of severe rotations. This retainer should be flexible to favor physiologic movement of retained teeth.

Duration of retention (box 43.3)

Retention is not required where the established occlusion will maintain the treatment outcome, e.g. corrected crossbite with adequate bite. Short-term retention spans 3–6 months with removable appliance and involves full-time wear for next 3 months except during meal times, followed by night-time wear for next 3 months. The medium-term retention spans over 1–5 years with a fixed retainer though a modified functional appliance or headgear included to the removable maxillary appliance can be used depending on the original malocclusion. Permanent retention is performed with cleft lip or palate where the prosthesis can be used as a retainer or in relation with the periodontal problems.

A fixed retainer can be replaced with a removable retainer after 21 years of age and then worn till the patient desires for maintaining the optimal dental alignment.

Theorems on retention

The first nine theorems were given by Riedel and the tenth theorem was given by Moyers.

• Theorem 1: “Teeth that have been moved tend to return to their former positions.”

• Theorem 2: “Elimination of the cause of malocclusion will prevent recurrence.”

• Theorem 3: “Malocclusion should be overcorrected as a safety factor.”

• Theorem 4: “Proper occlusion is a potent factor in holding teeth in their corrected positions.”

• Theorem 5: “Bone and adjacent tissues must be allowed to reorganize around newly positioned teeth.”

• Theorem 6: “If the lower incisors are placed upright over basal bone, they are more likely to remain in good alignment.”

• Theorem 7: “Corrections carried out during periods of growth are less likely to relapse.”

• Theorem 8: “The farther teeth have been moved, the less likelihood of relapse.”

• Theorem 9: “Arch form particularly in the mandibular arch cannot be altered permanently by appliance therapy.”

• Theorem 10: “Many treated malocclusions require permanent retaining devices.”

Requirements of retaining appliances

Retention appliances are passive orthodontic appliances that are used to hold the teeth moved by orthodontic treatment till the supporting tissues are reorganized. The requirements of a good retaining appliance are:15

1. It should restrain each tooth that has been moved into the desired position in directions where there are tendencies toward recurring movements.

2. It should permit the forces associated with functional activity to act freely on the retained teeth, permitting them to respond in as nearly a physiologic manner as possible. Retainers should be able to allow for functional occlusion.

3. It should be as self-cleansing as possible and should be reasonably easy to maintain in optimal hygienic condition.

4. It should be constructed in such a manner as to be as inconspicuous as possible, yet should be strong enough to achieve its objective over the required period of use.

Retention appliances

Retainers are classified into removable and fixed retainers (Table 43.1). To achieve the objectives, most orthodontists use a removable upper retainer and a fixed or removable lower retainer.

TABLE 43.1

Classification of retainers

| Removable Retainers | Fixed Retainers |

| Hawley retainer and modifications | Banded canine to canine retainer |

| Wrap around retainer | Bonded canine to canine retainer |

| Canine to canine clip on | Diastema maintenance |

| Tooth positioners | Antirotation band |

| Essix retainers/invisible retainer | Band and spur |

| Functional appliances | Pontic maintenance |

Removable retainers

Removable retention appliances serve effectively for retention against intra-arch stability. They are also effective in growth problems, wherein functional appliances or headgears are used as retention appliances.

Hawley retainer

Hawley retainer is the most commonly used retentive appliance (Fig. 43.2A). It incorporates clasps on molar teeth and a labial bow, which spans from canine to canine. The palatal or lingual portion is constructed of acrylic and covers the palatal mucosa. Because of the palatal coverage, it acts as a potential bite plane to control overbite. Hawley retainer can be made for upper or lower arch.

The drawback of standard Hawley retainer is when used in first premolar extraction cases, it causes the space to open because of the wedging effect.

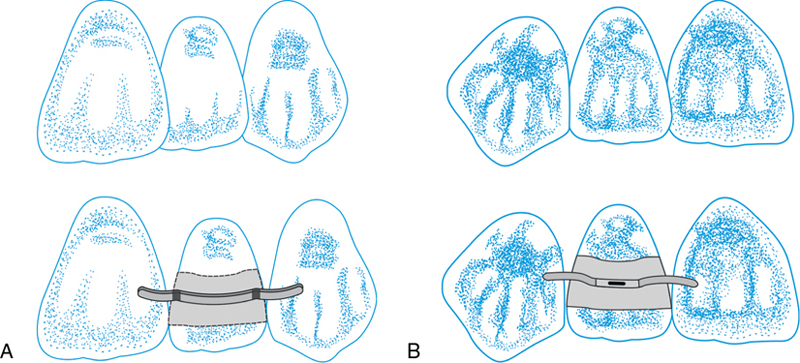

Modifications

1. Instead of short labial bow, a long labial bow can be used in first premolar extraction cases. This prevents wedging effect in extracted site (Fig. 43.2B).

2. Alternative design for extraction cases is to wrap the labial bow around the entire arch, without clasps. This is useful to close residual spaces also. This is called Begg’s retainer or circumferential maxillary retainer (Fig. 43.2C).

3. Another alternative in extraction case is to solder the labial bow to the Adams clasp (Fig. 43.2D). The action of labial bow holds the extraction space closed.

Removable wrap around or clip-on retainer

This consists of a wire reinforced plastic bar along the labial and lingual surfaces of the teeth, made with clear acrylic. This is used in cases where the periodontal support is inadequate. This retainer splints the teeth together firmly. This is a disadvantage of the retainer as the functional stimulus will not be transmitted to individual teeth.

Modified wrap around/canine to canine clip-on retainer

This is widely used in lower anterior region. It has the advantage, it can be used to realign lower incisors. It is well tolerated by the patient.

Positioners as retainer

Often, a case is treated to the point where only minor corrections and settling will produce the desired final result. To achieve this goal, Kesling designed an elastoplastic positioner that is particularly valuable in extraction cases. An impression is made at the time fixed appliances are removed, teeth are cut off the model and reset in the ultimate positions desired (using wax), and the positioner is then fabricated to this relationship (Fig. 43.3A).

While these appliances are usually made of rubber or plastic (Fig. 43.3B), they may also be constructed on hard or soft acrylic tooth positioner devised by Kesling is usually used as a finishing appliance. Sometimes this positioner itself can be used as retaining appliance.

Advantages of positioner

Disadvantages

Essix retainer/invisible retainer

Essix thermoplastic copolyester retainers are a thinner, but stronger, cuspid-to-cuspid version of the full-arch, vacuum-formed devices.16 The standard Essix canine to canine retainers are made from clear thermoplastics. It incorporates all the advantages of canine to canine clip-on retainer. In extraction cases, it is made to extend to cover the extraction site. It is esthetically acceptable.

An Essix appliance also has the capability of correcting minor tooth discrepancies (Fig. 43.4). The advantages are:

Functional appliances

Functional appliances are used in subjects who still have growth left. Activators and oral screen are commonly used.

Fixed retention appliances

Fixed retainers are used in conditions where long-term retention is required. It is indicated in conditions where intra-arch instability is anticipated.

Banded canine to canine retainer

Banded canine to canine retainer is used for maintenance of lower incisor position during growth (Fig. 43.5A). The retainer consists of fixed lingual bar attached to the canines or premolars in some cases. The fixed lingual bar is soldered to the canine bands on the lingual aspect.

Disadvantages

Bonded canine to canine retainer

A fixed lingual canine to canine retainer can be fabricated without bands by bonding to the lingual surface. It is attached only to the canines, resting passively against the lingual surface of central and lateral incisor (Fig. 43.5B). It is made from heavier wire to resist distortion. The ends of the wire are sandblasted to improve retention.

Modification

In cases of rotation and crowding correction, the lingual wire is bonded to one or more incisor teeth. In this situation, a flexible braided steel archwire is used.

Diastema maintenance

A fixed retainer is used to maintain diastema correction (Fig. 43.5C).

Antirotation band

This is used to maintain corrected single tooth rotation. The band on the rotated tooth has two spurs welded to it–labially and lingually. The spurs rest on adjacent teeth and prevent relapse.

Band and spur

Band and spur is used to hold incisor tooth that were labially or lingually placed (Fig. 43.6). This prevents the tooth from returning to its original position.

Maintenance of pontic or implant space

A fixed retainer is used to maintain space for a pontic. A shallow preparation is made in the enamel of the marginal ridges of the adjacent teeth to the extraction site. A section wire is bonded.

Active retainers

Relapse after orthodontic treatment necessitates some tooth movement during retention. Examples of active retainers are:

1. Typical Hawley retainer with the palatal acrylic portion trimmed to facilitate tooth movement.

2. Wrap-around retainers when activated can be used to close residual spaces due to banding procedures (Fig. 43.7A).

3. Spring retainers using facial and lingual acrylic with labial bows may be used for minor realignment of irregular lower incisors (Fig. 43.7B).

4. Use of activator or bionator in patients who show relapse after growth modulation treatment. Differential anteroposterior tooth movement will compensate for minor 2 or 3 mm relapse.

5. Headgear may be used in high-angle cases to control the eruption of molars.

6. If the relapse is moderate, a fixed appliance for retreatment should be considered.

Raleigh williams keys to eliminate lower incisor retention

Raleigh Williams has outlined six keys to eliminate lower anterior retention and improve post-treatment stability (Fig. 43.8).

• Key 1: The incisal edge of the lower incisor should be placed on the A-Pog line or 1 mm in front of it.

• Key 2: The lower incisor apices should be spread distally to the crowns. Apices of lateral incisors must be spread more than those of central incisors.

• Key 3: The apex of the lower cuspid should be positioned distal to the crown. The occlusal plane should be used as a positioning guide. This reduces the tendency of the canine to tip forward into the incisor area.

• Key 4: All the four lower incisor apices must be in the same labiolingual plane.

• Key 5: The lower cuspid root apex must be positioned slightly buccal to the crown apex.

• Key 6: Lower incisors should be slenderized. Flattening lower incisor contact points by slenderizing or stripping creates flat contact surfaces. Flat contacts surfaces help resist labiolingual crown displacement.

Table 43.2 outlines the retention objectives and the appliances that may be used.

TABLE 43.2

Retention: objectives and appliances used

| Objectives | Fixed and Removable Appliances Used | Comment |

| Arch-length and arch-width changes | Fixed: First molar to first molar, premolar to premolar or canine to canine cemented bands, with lingual adapted and soldered wire | Lingual wire is better because of lessened caries susceptibility, less restraint of growth processes and better esthetics |

| Removable: Acrylic palate or lingual horseshoe mandibular retainer, with or without clasps, rests or labial wire, as required | Full palate better for maxilla because of greater stability and resistance to displacement. Rests are advisable for mandibular retainer. Lower fixed lingual appliance is superior to removable type | |

| Removable: Elastoplastic intermaxillary positioner | Properly used, can effect minor corrections and help ‘settling in’. Bad taste and patient cooperation demands are disadvantages | |

| Rotation corrections | Fixed: Cemented bands with soldered spurs to mesial or distal, labial or lingual. United bands (labial frenum cases) | Often, overcorrection assists retaining appliance. Oral hygiene important to prevent decalcification around spur extensions |

| Removable: Acrylic palate with labial wire. Elastoplastic intermaxillary positioner | Excellent for maxillary anterior teeth. Most effective on incisor rotations (see disadvantages listed above) | |

| Changed axial inclination | Anterior segments: Acrylic palate and labial wire. Fixed labial or lingual retainer | Properly fabricated, quite effective retainer. Seldom used for axial inclination alone |

| Posterior segments: Removable acrylic palate with labial wire, bands and spurs and united bands | Fixed retainer for axial inclination used most in canine-first premolar region | |

| Mesiodistal relationship changes | Fixed: Soldered inclined plane on maxillary lingual arch, soldered to cemented molar bands. Soldered inclined planes. May be cast or wrought wire. Not used often and less effective than lingual ‘guide plane’ on molar bands | Effective while in use, but may cause labial inclination of mandibular incisors and dual bite when removed |

| Removable: Acrylic palatal retainer with clasps and inclined plane lingual to maxillary incisors | Used most frequently, in conjunction with overbite correction and retention | |

| Removable: Elastoplastic intermaxillary positioner, part-time extraoral orthopedic force | Quite effective as long as it is used but, like fixed guide plane, may cause procumbency of lower incisors and dual bite. Of significant importance in basal malrelationships, when growth still remains | |

| Vertical dimension changes; overbite correction | Fixed: Acrylic or metal splints cemented to posterior segments (diagnostic splints). Cast overlays, full-mouth reconstruction. Bite plane from fixed lingual arch, soldered to cemented first molar bands (guide plane) | Used primarily in temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disturbances prior to permanent reconstruction |

| Removable: Acrylic palatal appliance with clasps and horizontal or inclined plane lingual to maxillary incisors, separating occlusal surfaces of upper and lower buccal segments | Used when orthodontic procedures cannot affect a permanent change, whereas bite plane soldered to lingual arch is designed to stimulate and hold eruption of the posterior teeth–permanent correction. Used most frequently, both as treatment adjunct and for retention; also as diagnostic appliance in TMJ disturbances. Bite plate may be modified for other uses. Loses efficiency if not used during mastication | |

| Holding spaces created by therapy | Fixed: Cemented bands with soldered bar in between. Functional and nonfunctional | Most frequently used space maintainer. Contoured stainless metal crowns may also be used |

| Fixed: Cemented band and cantilever-type spur. Original tooth-moving appliance with ligated arch segment | Less effective over any long period of time. Satisfactory for short period of time | |

| Removable: Acrylic palatal or mandibular horseshoe appliance, with clasps and necessary spurs, or pontics in edentulous areas | Particularly effective for maxillary anterior spaces. May be used as modified bite plate, or Hawley-type retainer, with labial wire. Fixed retainers more desirable in mandibular arch |

We seem to know less about the retention phase of orthodontic management than any other. Much of the knowledge that we have is empiric and the retention procedures are largely arbitrary, being based on a general rule and not the demands of the particular case. There is no question that the stability of the end-result is a major requisite. No matter how long teeth are splinted in abnormal positions with a retaining appliance, the tissue will not reorganize to hold them, if they are not in balance with environmental forces.