33

General Surgery

After studying this chapter, the learner will be able to:

• Describe the pertinent surgical anatomy of the breast.

• Describe the surgical procedures used to diagnose breast cancer.

• Identify the pertinent anatomy of the abdominal organs within the peritoneal cavity.

• Discuss the differences between laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy.

• List the types of anastomoses used for intestinal surgery.

• List several surgical diagnostic procedures used to evaluate abdominal trauma.

• Differentiate between direct and indirect inguinal hernia.

• Discuss the psychological effects of limb amputation on the patient under regional anesthesia.

Key Terms and Definitions

-itis Inflammation of an organ or part.

-ectomy Removal of an organ or part.

-otomy Opening into an organ.

-ostomy Creation of an opening in an organ or part intended to remain open permanently or for an extended time.

-orrhaphy Repair and fixation of an organ or part.

Anastomosis Surgically joining two lumens to create a patent passage.

Laparotomy Surgically opening the abdomen for an exploratory or definitive surgical procedure.

Resection Removal of a segment of an organ or part.

Stoma A surgically created opening in an organ that forms an exit from the body.

Evolve Website

Evolve Website

• Historical Perspective

• Tips for the Scrub Person and Circulating Nurse

• Student Interactive Questions

• Glossary

Special Considerations for General Surgery

The discipline of general surgery provides the fundamentals for surgical practice, education, and research. The definition of general surgery agreed on by the American Board of Surgery and the Residency Review Committee for Surgery serves as the basis of graduate education and certification as a specialist in surgery. The following principles are inherent in general surgery:

• A central core of knowledge and skills common to all surgical specialties (e.g., anatomy, physiology, metabolism, pathology, immunology, wound healing, shock and resuscitation, neoplasia, and nutrition)

• The diagnosis and preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative care of patients with diseases of the alimentary tract; the abdomen and its contents; breast; head and neck; endocrine system; and vascular system (excluding intracranial vessels, the heart, and vessels intrinsic and immediately adjacent thereto)

• Responsibility for the comprehensive management of trauma and critically ill patients with underlying surgical conditions

In a community hospital, the practice of general surgery usually encompasses many aspects of surgical care. In larger teaching facilities, general surgery services are commonly specialized (e.g., breast, biliary tract, gastrointestinal, or colon and rectal surgery). The introduction of surgical specialties was the outgrowth of increased knowledge of the etiology of disease and specialized treatment of all parts of the body. General surgery, the basis for all specialties, has decreased in breadth as specialization has increased. The anatomic parts not specifically delegated to specialists have remained in the realm of the general surgeon. Other surgical disciplines depend on general surgeons for clinical collaboration in reconstruction involving the gastrointestinal and vascular systems.

The scope of this chapter focuses on procedures commonly categorized as general surgery. Technologic advances characterize many aspects of surgical practice. The general surgery team of today should be familiar with endoscopic techniques for diagnosis and treatment. Electrosurgery, lasers, and surgical staplers are part of the setup for standard general surgery. Patients are best cared for when the entire perioperative team understands the principles of available technologies and has clinical experience in the safe use of these technologies. The following are examples of technologic applications and the associated aspects of patient care:

1. Malignant lesions, especially those of the breast, thyroid, and gastrointestinal tract, account for a large percentage of surgical interventions. The extent of the surgical excision of a lesion may be determined only after thorough exploration during a surgical procedure, sometimes scheduled as a diagnostic laparoscopy or as a biopsy and frozen section.

a. Although the patient has been informed preoperatively of an anticipated procedure, the unknown factor is cause for apprehension. The circulating nurse should provide comfort while the patient is awake. A biopsy or endoscopic procedure may be performed with the patient under local anesthesia and with or without moderate sedation.

b. A definitive open or laparoscopic surgical procedure may be performed on the basis of results of the biopsy and frozen section or endoscopic examination while the patient is under anesthesia. The scrub person should be prepared with two draping and instrument setups, depending on the diagnosis established and the surgeon’s plan for the surgical procedure. Anticipated equipment and supplies should be available without delay.

2. The types of anesthesia administered are as varied as the types of surgical procedures. Blood pressure, pulse, respiration, electrocardiogram (ECG), and pulse oximetry should be monitored for all patients, regardless of the anesthetic used. Personnel responsible for monitoring patients should be qualified to interpret data, assess the patient, and effect corrective action in the event of an untoward reaction.

3. Patients are placed in the supine position for many general surgical procedures. Extra padding and accessory positioning aids should be available for other positions. The average OR bed can accommodate 350 lbs of body weight. Obese patients require a suitable bed capable of managing body weight.

4. Draping for abdominal incisions is usually standardized. Modifications are necessary for other sites, such as the breast or neck.

5. Instrumentation is quite varied and suited to function in a specific anatomic area. For example, gastrointestinal procedures require crushing clamps (e.g., Pean clamps to occlude the intestinal lumen before resection) and atraumatic clamps (e.g., Bainbridge clamps to protect delicate tissues). Included in all procedures are instruments for exposing, dissecting, grasping, clamping, suctioning, and suturing. For atraumatic retraction, various lengths of umbilical tape, hernia tape, or vessel loops may be placed around vessels or other structures to retract them. These materials should be included in the count.

6. Some procedures require minimal access and are adaptable to ambulatory surgery; others are extremely extensive. More complex procedures, such as colectomy and cholecystectomy, are often performed endoscopically and require less in-house hospitalization.

7. The electrosurgical unit (ESU), argon beam coagulator, laser, endoscope, laparoscope, and/or ultrasound transducer may be used during the procedure.

8. In complex open and laparoscopic abdominal and pelvic procedures, the following should be noted:

a. Indwelling Foley or ureteral catheters may be inserted preoperatively to decompress the urinary bladder and monitor urinary output. Some surgeons may request the placement of ureteral catheters to stent and outline the ureters for complex dissection of abdominal organs. This will require a sterile cystoscopy setup, stirrups, and a urologist before the general surgery procedure of the abdomen begins.

b. Nasogastric (NG) tubes may be passed before or during the surgical procedure to decompress the stomach and bowel. The anesthesia provider inserts the NG tube after the induction of anesthesia. The NG tube may be removed at the end of the surgical procedure.

c. After the abdominal cavity is entered, single free 4 × 4 sponges should be removed from the field. They are used only while folded and secured on a sponge stick. Wet or dry laparotomy sponges are used in the abdominal cavity. A small dissector (peanut, cherry, or Kitner) is always clamped in a forceps before being handed to the surgeon.

d. Before the peritoneum is incised, suction should be available and ready for immediate use, especially in biliary or intestinal procedures or when fluid or blood may be anticipated in the peritoneal cavity. If a cell saver is used for blood salvage, the suction tip for blood is kept separate from the suction tip for other fluids.

e. Drains may be exteriorized through a stab wound in the adjacent abdominal wall before closure. A nonabsorbable monofilament suture on a small cutting needle will be used to secure the drain to the skin. Drains are discussed in Chapter 29.

f. Contaminated items, such as those used to dissect and/or anastomose intestinal segments, are isolated in a basin on the back table.

g. Before closure, the wound is irrigated with warm, sterile, normal saline solution to remove blood and debris.

h. Retention sutures may be used to give additional strength to wound closure. Rubber or silicone bumpers or a wound bridge may be used to protect the skin from tension exerted by the adjunct wound closure sutures. Wound closure is discussed in Chapter 28.

9. Assorted sizes of drains, tubes, drainage bags, and wound suction systems should be available. Care is taken to ensure that the patient is not latex sensitive.

10. Irrigating solutions should be body temperature (not to exceed 110° F) when they are used. All radiopaque contrast media, anticoagulants, and solutions on the instrument table and their delivery devices are clearly labeled to avoid any error in administration. Hypodermic syringes with needles are not recapped by hand. Care is taken to monitor the volumes of fluid used for irrigation.

11. Blood loss and urinary output are recorded on the perioperative record. Anesthesia personnel document the amount of intravenous (IV) solution and medications administered during the case.

12. Specimens are carefully labeled and sent for processing as appropriate. Care of specimens is discussed in Chapter 22.

Breast Procedures

The mammary glands are bilateral organs (modified sweat glands) lying in the superficial fascia of the pectoral area (Fig. 33-1). They are attached to the underlying muscles by loose areolar tissue and suspended by Cooper ligaments. The breasts extend from the border of the sternum to the anterior axillary line (tail of Spence) and from approximately the first to the seventh ribs.

The breasts are highly vascular. The blood supply is derived laterally from the thoracic branches of the axillary, intercostal, and internal mammary arteries (Fig. 33-2). Venous drainage forms an anastomotic circle around the base of the nipple, with branches draining the circumference of the gland into the axillary and internal mammary veins. Lymphatic drainage follows the same path as the venous system and empties into the thoracoabdominal and lateral thoracic vessels. Innervation arises from the anterior and lateral cutaneous nerves of the thorax.

General surgery on the breast for males and females includes diagnostic procedures and those performed for known pathologic disease, such as cancer. Diagnostic techniques include mammography, ultrasonography, fine-needle aspiration (FNA), and the traditional tissue biopsy.

The desired surgical procedure should be determined on an individual basis after careful diagnostic studies and histologic diagnosis. Size, location, and type of diseased tissue and stage of malignancy are important considerations. No single surgical procedure is suitable for all patients.

Incision and Drainage

Surgical opening of an inflamed and suppurative area is most often carried out because of infections in the lactating breast. The cavity is usually irrigated, and the wound is packed and allowed to heal by granulation. The causative organism is often Staphylococcus.

Breast Biopsy

The average size of lumps found by women who do and do not practice breast self-examination (BSE) is illustrated in Chapter 22 (see Fig. 22-3). All breast masses are considered malignant until proved benign. To determine the exact nature of a mass in the breast, tissue is removed for pathologic examination. The size and location (Fig. 33-3) of the lesion influence the type of biopsy:

• Fine-needle aspiration: A 22- or 25-gauge needle attached to a syringe is inserted into the tumor mass. A few cells are aspirated and sent to the pathology laboratory for cytologic studies. This may be performed in conjunction with a mammogram (mammographic breast biopsy) or as an office procedure. FNA also may be used to evacuate fluid from benign cysts.

• Core biopsy: For this type of incisional biopsy, a large-bore trocar needle, such as a Tru-Cut or Vim-Silverman biopsy needle, is inserted into the mass. A core of suspected tissue is withdrawn for histologic examination. Any retrieved fluid is also sent to the pathology laboratory.

• Stereotactic breast biopsy: The patient is placed prone on a special x-ray table, and her breast is placed in an opening in the table. A computer-guided system is used to digitally locate and pinpoint nonpalpable breast lesions. The biopsy is obtained with a vacuum-assisted Mammotome while the patient is under local anesthesia.

• Incisional biopsy: The mass is incised, and a portion is removed for histologic examination.

• Excisional biopsy: The entire mass is removed for pathologic study.

• Sentinel node biopsy: The breast mass is injected with a radioisotope (technetium) in the radiology department several hours before the planned surgical procedure. In the OR, the tumor is injected with a dye containing isosulfan blue that is taken up by the lymph nodes of the breast. The nodes are excised before the primary mass.

• A sterile Geiger counter probe is used on the field to locate the areas of radioactivity. The specimens are sent to pathology for immunohistochemical staining. Lead containers are used to house the specimens for 24 hours before the pathologist examines them.

• J-wire or needle localization in radiology department: The mass is identified on mammography, and the patient undergoes the insertion of a wire into the mass in the radiology department under fluoroscopy (Fig. 33-4). The wire remains taped in place as the patient is taken to the OR. The mass is excised with the wire intact (Fig. 33-5). The specimen is taken back to the radiology department to be x-rayed as a confirmation that the wire is still in the mass. After the confirmatory x-ray, the specimen is taken to pathology.

• Fiberoptic ductoscopy: A flexible 0.9-mm scope with a 0.2-mm working channel is used in the ductal lumens of the breast. Studies have shown that 85% of breast cancer originates in the ductal system in the epithelial lining. The image is enlarged to 200 times by magnification. The scopes are approved for 10 uses each by the U.S Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

• The ducts may need to be dilated with lacrimal probes before inserting the scope. Specimens can be obtained by this method, and ductal lavage can be performed for cell studies.

Preoperatively, the surgeon discusses with the patient possible findings and treatment options. The patient may agree to an immediate definitive surgical procedure such as mastectomy or lumpectomy if warranted by the biopsy and frozen section results. Two separate prepping, draping, and instrument sets are necessary to avoid mixing cancerous cells of the breast specimen with the freshly prepared reconstructive site. The team should change gown and gloves.

To minimize disfigurement, many women with early operable breast cancer (a mass less than 5 cm) opt for limited resection followed by radiation and chemotherapy (Fig. 33-6). The difference between tumor and deep tumor-free resection margin remains an important consideration in determining the most appropriate type of mastectomy incision (Table 33-1).1

Lumpectomy

Lumpectomy, a partial mastectomy, consists of removal of the entire tumor mass along with at least 1 to 2 cm of surrounding nondiseased tissue. This procedure is recommended for peripherally located tumors that measure less than 5 cm. Lumpectomy is contraindicated if breast size precludes postoperative radiation or if negative margins around the tumor cannot be obtained. Compared with mastectomy, the lumpectomy incisions are less disfiguring.

Breast conservation, the surgical treatment of choice for many women with breast cancer, includes a lumpectomy to excise a primary tumor and axillary node dissection followed by radiation therapy. This approach maintains the appearance and function of the breast (Fig. 33-7). The surgeon may prefer to perform the lumpectomy first, followed by axillary dissection (Fig. 33-8).

The patient should be reprepped and redraped between procedures. A separate set of instruments is used for each procedure to avoid possible tumor cell implantation in the axilla. A transverse incision for axillary dissection, approximately 1 cm below the axillary hairline, extends from the pectoralis major muscle anteriorly to the latissimus dorsi muscle posteriorly. Lymphoareolar tissue between these muscles is removed—usually at least 10 lymph nodes.

Segmental Mastectomy

In a segmental mastectomy, a wedge or quadrant (quadrantectomy) of breast tissue is removed; this wedge includes the tumor mass and the lobe in which it is growing. Some surgeons explore the axilla and take a few lymph nodes for histologic studies.

Simple Mastectomy

In a simple mastectomy, the entire breast is removed without lymph node dissection. A simple mastectomy may be performed for a malignancy that is confined to breast tissue with negative nodes, as a palliative measure for an advanced ulcerated malignant tumor, or for the removal of extensive benign disease. Skin grafting may be necessary if the primary closure of skin flaps would create unacceptable tension. Skin flaps are then loosely approximated, and grafts taken from the thigh are applied to the remaining defect. A latissimus dorsi or transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM) flap may be preferred for reconstruction.

A subcutaneous mastectomy may be performed for patients with chronic cystic mastitis who have had multiple previous biopsies, for patients with multiple fibroadenomas or hyperplastic duct changes, and for patients with central tumors that are noninvasive in origin. Some patients with a strong family history of breast cancer may have prophylactic mastectomies as a precaution. All breast tissue is removed, but the overlying skin and nipple remain intact. A prosthesis may be inserted at the time of the surgical procedure, depending on the surgeon’s decision and the patient’s wishes.

TABLE 33-1

| Stage I | Stage II | Stage III | Stage IV |

| Size | |||

| ≤1-2 cm | 2-5 cm | ≥5 cm | Large and fully integrated with surrounding tissue |

| Location | |||

| Confined to breast | Breast mass with or without suspicious axillary lymph nodes | Breast mass with palpable, fixed axillary, and/or subclavicular lymph nodes | Distant metastasis; extension to skin |

| May or may not extend to pectoral fascia or muscle | Mass may be adherent to surrounding tissue | Lymphedema above or below the clavicle | |

| No distant metastasis | No distant metastasis | ||

| Surgical Options | |||

| Segmental mastectomy | Total mastectomy | Modified or radical mastectomy | Radical or extended radical mastectomy |

| Breast conservation surgery for stages I and II lumpectomy with axillary node dissection and radiation therapy | |||

Modified Radical Mastectomy

A modified radical mastectomy is usually performed for infiltrating ductal and localized small malignant lesions. The term modified encompasses various techniques, but all include removal of the entire breast (total mastectomy). In addition, all axillary lymph nodes are resected. The underlying pectoralis major muscle is left in place; the pectoralis minor muscle may or may not be removed. In patients with small lesions and no metastases, breast reconstruction may be performed immediately or a few days after the procedure.

Radical Mastectomy

A radical mastectomy is performed to control the spread of malignant disease from large infiltrating cancers. After a positive finding on the tissue biopsy, the entire involved breast is removed along with the axillary lymph nodes, the pectoral muscles, and all adjacent tissues. During the surgical procedure, skin flaps and extensive exposed tissue are covered with moist packs for protection. The chest wall and axilla are irrigated with sterile water before closure. Skin grafts are usually required to cover the defect.

Extended Radical Mastectomy

Cancer is a disease that grows both deeply and laterally. An extended radical mastectomy is indicated when malignant disease is present in the medial quadrant or subareolar tissue because it tends to spread to the internal mammary lymph nodes. The involved breast is removed en bloc along with the underlying pectoral muscles, axillary contents, and upper internal mammary (mediastinal) lymph node chain. This procedure is more difficult than a classic radical mastectomy.

Considerations for Female Breast Procedures

For a breast procedure, the patient is placed in the supine position; the involved side is positioned close to the edge of the OR bed, and the arm on the affected side is extended on an armboard. The affected side is elevated with a small pillow, or the OR bed is tilted. The anterior part of the chest is prepped from the chin to the umbilicus and from the axilla on the affected side to the nipple line of the opposite breast. The entire arm on the affected side is included in this preparation. General anesthesia is usually preferred for a mastectomy because local infiltrate may obscure a tumor.

Because of the vascularity of breast tissue, a laser or electrosurgery is commonly used for hemostasis. Larger vessels may require a tie. Patients undergoing a mastectomy should be watched for excessive bleeding. Some surgeons prefer to irrigate the mastectomy wound with sterile water instead of sterile normal saline solution to crenate (shrivel or shrink) cancerous cells. The circulating nurse should check with the surgeon about the care of the specimen for the pathologist. The specimen is placed in sterile normal saline solution if estrogen or progesterone receptor studies are to be performed. Formalin is used for permanent sections.

A bulky compression dressing and Surgi-Bra may be applied in the OR. Depending on the amount of tissue resected, a closed-wound suction system may be inserted to remove blood and serum and to prevent pressure necrosis of skin flaps.

Lymphedema of the arm on the affected side is a possible complication after mastectomy causing the arm to painfully swell and lose function. The patient is highly susceptible to infection. When axillary dissection is performed, the lymphatic structure of the arm is compromised causing primary lymphedema.1 Secondary causes include radiation, extreme inflammation, or infection. Although lymphedema can be an immediate problem, it most frequently builds up over time during the postoperative period. The severity is classified by the degree of pitting and loss of arm mobility. Patients experience neck and back pain as the arm becomes heavier with accumulated lymph. Obesity significantly increases the risk of lymphedema development.1 The enlarged arm causes self-perception issues and is a constant reminder of cancer treatment.

Management of lymphedema involves one or more of the following: 1) manual drainage; 2) compression garment/sleeve; 3) physical exercise; and 4) meticulous skin care. Some patients are candidates for a liposuction procedure to reduce the size of the arm. The patient must wear a compression sleeve at all times after a reduction procedure for life to keep the arm in a reduced state. Lymphatic grafts to the axilla from the medial thigh have been used with some success, however, the risk for lymphedema of the donor leg is possible.

Patients who have undergone a mastectomy are often referred to the Reach to Recovery rehabilitative program. In this program, volunteers who have had mastectomies visit patients, share information with them, and give them encouragement.

Abdominal Procedures

Biliary Tract Procedures

The gallbladder is located in the right upper quadrant in a fossa under and immediately adjacent to the right lobe of the liver (Fig. 33-9). The gallbladder is a thin-walled sac and has a normal capacity of 50 to 75 mL of bile. Bile secreted by the hepatic cells enters the intrahepatic bile ducts and progresses to the common bile duct. When not needed for digestion, bile is diverted through the cystic duct into the gallbladder, where it is stored. When bile is needed, the gallbladder contracts and empties bile into the cystic duct; the bile flows into and through the common duct into the duodenum.

Gallstones are concretions of elements of bile, particularly cholesterol (about 50%), and may be found in the gallbladder or in any portion of the extrahepatic biliary duct system. Brown stones are usually fatty acids, and black stones are composed of inorganic salts. The incidence of stones, referred to as cholelithiasis, increases with age and is more prevalent in women and in people who are obese.

Acute or chronic inflammation of the gallbladder, common duct stones (choledocholithiasis), carcinoma, and the congenital absence of bile ducts (biliary atresia) are the most common indications for a surgical procedure. Obstructive jaundice, which is potentially fatal, may be a sign of ductal cholelithiasis or the presence of a neoplasm. The cause of jaundice should be determined and the condition relieved to spare the patient irreversible progressive liver damage. Biliary stones are sent as dry specimens if removed separately.

The greatest hazards of biliary tract surgery are associated with the anatomic relationships of the ducts and the cystic artery and with pathologic changes in the gallbladder. Complications include hemorrhage and injury to the extrahepatic biliary duct system. Spilled bile can cause peritonitis postoperatively.

Ultrasonography, nuclear imaging such as hepatic intraductal assay (HIDA) scan, and computed tomography (CT) scanning are used for the diagnosis of gallbladder disease. Oral and IV cholecystography may be used for visualization of the gallbladder in the initial evaluation of patients with biliary symptoms.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography also may be performed, usually by a gastroenterologist, to identify stones, tumors, inflammatory lesions, or an obstruction. A flexible fiberoptic duodenoscope is introduced with the patient under IV sedation and with the use of a topical anesthetic to control the gag reflex.

Contrast media is injected to opacify the entire biliary tract and pancreatic duct under fluoroscopy. Care is taken when preparing the contrast in the syringe without air bubbles. Air bubbles will appear like stones on x-ray. Some definitive therapy is possible during this procedure, such as stone retrieval (endoscopic papillotomy), stent insertion, and sphincterotomy. A percutaneous transhepatic puncture is used to resect tumors for biopsy, dilate strictures, place stents in the bile duct, and establish temporary drainage through ducts. A contrast medium can be injected for a cholangiogram.

Cholecystectomy

Gallbladder disease is cured by removal of the gallbladder in a procedure referred to as a cholecystectomy—the most common surgical procedure performed on the biliary tract. A cholecystectomy is performed to relieve the gastrointestinal distress common in patients with acute or chronic cholecystitis (with or without gallstones); it also removes a source of recurrent sepsis. Persistent infection in the biliary tract may cause recurrent stones.

For an open cholecystectomy, the patient is placed in the supine position. As requested by the surgeon, the right upper quadrant may be slightly elevated on a gallbladder rest or pillow after the induction of general anesthesia. The OR bed may be tilted slightly into a reverse Trendelenburg’s position so that the abdominal viscera gravitate downward, away from the surgical area.

Open Abdominal Cholecystectomy

With an open abdominal cholecystectomy, the gallbladder is usually exposed through a right subcostal incision (Kocher incision) that may be extended over to the midline at the level of the xyphoid. The incision should be adequate for good exposure of the gallbladder and bile ducts. After exploration of the abdominal cavity, laparotomy packs are used to wall off the surrounding organs for exposure.

The bilious contents of the gallbladder may be aspirated to prevent bile from spilling into the peritoneal cavity—a potential source of peritonitis, especially if the gallbladder is inflamed and tightly distended. The cystic duct, cystic artery, hepatic ducts, and common bile duct are accurately identified.

After palpation of the ducts for stones, the cystic duct and artery are ligated with hemostatic clips and divided. Using blunt dissection, the gallbladder is freed and removed from the liver and its fossa (Fig. 33-10). Some surgeons use ESU and/or neodymium:yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) or holmium (Ho:YAG) laser for sharp dissection and coagulation. Stones removed as part of the specimen should be sent to the pathology department for analysis and documentation. If bile leakage or hemorrhage has been excessive, a sump drain or closed-wound suction drain may be placed in the subhepatic space and brought out through a stab wound after copious intraabdominal irrigation.

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

With a laparoscopic cholecystectomy the patient is supine in a slight to moderate reverse Trendelenburg’s position. A rigid fiberoptic laparoscope is inserted through a sheath into the peritoneal cavity. In conventional laparoscopy multiple trocars are inserted through triangulated puncture wounds in the right upper quadrant: one or two just right of midline, with the uppermost trocar slightly below the xyphoid and costal margin and the other midway to the umbilicus; one laterally in an anterior axillary line above the iliac crest at the costal margin; and another in a midclavicular line slightly above the level of the umbilicus and 2 cm below the rib. The location of puncture sites will vary according to patient size and surgeon preference (Fig. 33-11).

Newer technology employs an open laparoscopic method where a single incision is made at the umbilicus and a flexible multilumen port is inserted through which insufflation and additional instruments are placed. A Veress needle is not used. Single-incision laparoscopy is discussed in Chapter 32.

A camera attached to the laparoscope allows the surgeon to view the manipulation of instruments through the sheaths of these trocars. Viewing monitors are positioned on each side of the head of the OR bed (Fig. 33-12). With this procedure, the fundus of the gallbladder is grasped through one or more lateral ports and held by the assistant. After careful dissection, the surgeon ligates and divides the cystic duct and artery with suture loops or clips. A laser, an ESU, or microscissors may be used to transect these structures.

• FIG. 33-11 Laparoscopic setup. A, Position of personnel for a basic laparoscopy. B, Trocar placement is determined by the target organ position. C, Trocars used vary in size according to position of function for dissection and hemostasis.

The gallbladder is freed, most often by using an ESU or by using argon, potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP), or a contact Nd:YAG or Ho:YAG laser. The gallbladder is usually lowered into an Endo Catch pouch and aspirated to remove bile and collapse the sac. It may then be removed in one piece or cut into sections and withdrawn through the periumbilical incision.

• FIG. 33-12 Laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A, Placement of personnel and monitors for gallbladder removal. B, Trocar placement for gallbladder removal.

The perioperative team must be ready to convert from laparoscopic to an open procedure in the event of bleeding or other difficulty during the procedure. Supplies and instrumentation should be immediately available. It is advantageous to have precounted sets in the room during these procedures.

Common Bile Duct Exploration

Concomitant exploration of the common duct is often but not routinely performed during cholecystectomy. Curved stone forceps, small malleable scoops, dilators of various sizes, balloon catheters, stone baskets, and nylon brushes are useful in clearing the hepatic and biliary ducts of stones to prevent them from lodging in the duct and causing subsequent obstructive jaundice.

Palpable stones, jaundice with cholangitis, and dilation of the common bile duct are indications for exploration. A T-tube drain may be inserted to stent the duct and provide postoperative drainage. The surgeon may choose other intraoperative techniques to identify unsuspected stones, pathologic conditions, or anatomic variations in the hepatic duct system.

Intraoperative Cholangiograms

X-rays are obtained during either open abdominal or laparoscopic procedures. The radiology department is notified in advance if a cholangiogram is anticipated. To check for patient position, scout films should be obtained when the patient is initially positioned on the OR bed, before the procedure is started. The circulating nurse should assess the patient for allergies or sensitivities to contrast media and should ensure that the OR bed has an x-ray top or can be equipped for x-ray or fluoroscopy. Most facilities use digital x-rays.

The radiology technician returns to the OR when the surgeon is ready for films. Cholangiograms may be obtained after the gallbladder is removed or before the cystic duct and artery are ligated. A radiopaque contrast medium, usually diatrizoate sodium (Hypaque or Renografin), is injected into the cystic duct or common bile duct with a 50-mL syringe.

Unless fluoroscopy is used, a series of three or four x-rays are obtained and displayed in digital format. Before each exposure, the surgeon injects contrast media through a Cholangiocath (a plastic catheter inserted into cystic or common duct), cannula, or direct needle puncture in the common duct (Fig. 33-13). Instruments are removed from the field to the extent possible to minimize the obstruction of structures on the x-rays. The field is covered with a sterile barrier before the x-ray machine or C-arm is positioned over the patient. Sterile x-ray tube and C-arm covers are commercially available. All other radiologic precautions for patient and personnel safety and shielding should be observed.

Ultrasonography

Ultrasonography, a noninvasive technique, takes less time and does not have the radiation hazards of intraoperative cholangiograms. A sterile ultrasound probe is manipulated along the common bile duct from the liver to the duodenum. The probe transmits high-frequency sound waves back to the ultrasound unit in the form of echoes, which are displayed on a screen as black-and-white real-time images. To enhance the transmission of ultrasound waves, the abdominal cavity is irrigated with warm normal saline solution. Density in tissue causes sound waves to echo in altered patterns and directions. Gallstones appear as bright echoes, often with an acoustic shadow. Photographs or video can be obtained to document the findings of ultrasonography.

Choledochoscopy

Intraoperative biliary endoscopy provides image transmission and illumination, thus allowing the surgeon visual guidance in exploring the biliary system. Intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts can be visualized with a flexible fiberoptic choledochoscope introduced into the common duct. To provide distention of the biliary tract, normal saline solution must continuously flow through the irrigation channel.

Stones are easily seen and are usually free-floating under the pressure of the irrigating solution. A flexible stone forceps or a basket or a balloon-tipped biliary catheter may be inserted through the instrument channel of either a rigid or flexible scope to allow manipulation of a stone under direct vision. A biopsy forceps may be inserted to obtain a tissue sample. An Nd:YAG laser fiber may be used through the choledochoscope to crush bilirubin stones in the distal common hepatic duct; this allows easy removal of the stones.

Cholelithotripsy

Cholelithotripsy is a noninvasive procedure in which high-energy shock waves are used to fragment cholesterol gallstones. The procedure is performed under IV sedation or general anesthesia. The patient is usually placed in the prone position, but may also be in the supine or lateral position, on a lithotripter table, or submerged in a water bath. Spark-gap shock waves generated from an electrode pass through a fluid medium into the body until they reach the stone, which is focused with an ultrasound probe and computer.

The shock waves are synchronized with the R waves of the patient’s cardiac rhythm, which is monitored by ECG to avoid dysrhythmias. Each shock pulverizes the stones into small fragments which then pass through the bile duct. This passage may be aided by oral administration of deoxycholic acid (ursodiol) taken daily after lithotripsy to dissolve the fragments.

Choledochostomy and Choledochotomy

With choledochostomy, a T-tube is used to drain the common bile duct through the abdominal wall. A choledochotomy is the incision of the common bile duct for the exploration and removal of stones. Intraoperative cholangiography may be performed before and after exploration and/or stone removal. The duct is irrigated after calculi are removed. Patency of the duct and of the ampulla of Vater is investigated, often through a choledochoscope. If a neoplasm is found during exploration, resectability is determined; many tumors of the liver or pancreas are inoperable.

Cholecystoduodenostomy and Cholecystojejunostomy

Either a cholecystoduodenostomy or cholecystojejunostomy is performed to relieve an obstruction in the distal end of the common duct. Through anastomosis, these procedures establish continuity between the gallbladder and either the duodenum or jejunum. Careful evaluation precedes the surgical procedure.

Cholecystoduodenostomy and cholecystojejunostomy are bypass procedures to avoid further obstructive jaundice, but they do not solve the problem. Common causes of the obstruction are calculi, stricture of the duct, or neoplasms of the duct, ampulla of Vater, or pancreas.

Choledochoduodenostomy and choledochojejunostomy are side-to-side anastomoses between the duodenum or jejunum and the common duct. These procedures are carried out for difficult or recurrent biliary or pancreatic obstruction as a result of benign or malignant disease.

Liver Procedures

The liver, the largest gland in the body, is divided into left and right segments (or lobes) and is located in the upper right abdominal cavity beneath the diaphragm (Fig. 33-14). Part of the stomach and duodenum and the hepatic flexure of the colon lie directly beneath the liver. A tough fibrous sheath, the Glisson capsule, completely covers the organ; the tissue within this capsule is very friable and vascular. The hepatic artery, a branch of the celiac axis, maintains the arterial supply. Blood from the stomach, intestine, spleen, and pancreas is carried to the liver by the portal vein and its branches.

The many functions of the liver include forming and secreting bile, which aids digestion; transforming glucose into glycogen, which it stores; and helping to regulate blood volume. The liver is vital for the metabolic functioning of the body. It metabolizes fats, proteins, and carbohydrates; synthesizes cholesterol; excretes bilirubin; and secretes hormones. The liver has remarkable regenerative capacity, and up to 80% of it may be resected with little or no alteration in hepatic function.

Liver function tests are used to assess the degree of functional impairment and to evaluate liver activity and reserve. Most of these tests involve taking a series of blood samples from the patient for specific studies. Ascites may result from impaired liver function.

Liver Needle Biopsy

A percutaneous needle biopsy may help establish a diagnosis of liver disease. Because the procedure is performed with the patient under local anesthesia, moderate sedation, or monitored anesthesia care (MAC), the patient should be instructed to take several deep breaths and then hold the breath and remain absolutely still while the needle is inserted. Failure of the patient to cooperate can cause needle penetration of the diaphragm or hepatic injury and result in hemorrhage, a serious complication. Leakage of bile into the abdominal cavity may produce chemical peritonitis, an additional hazard.

After skin preparation and the induction of local anesthesia (with the patient in the supine position), a Franklin-Silverman or Tru-Cut biopsy needle is introduced into the liver via a transthoracic intercostal or transabdominal subcostal route. The needle is rotated to separate a small core of tissue, and it is then withdrawn to remove the specimen. As soon as the needle is removed, the patient is told to resume normal breathing and is assisted to turn onto his or her right side to compress the chest wall at the penetration site and prevent the seepage of bile or blood.

Slight bleeding may follow a liver biopsy; the patient’s prothrombin time is checked. This method of biopsy is not used if the patient has a coagulopathy.

In select patients under local anesthesia, a laparoscopic-assisted approach may be used to enhance visualization of the biopsy site. The anterior abdominal wall is elevated with a low volume of carbon dioxide insufflation or a planar lift device without insufflation. The biopsy needle is inserted through the abdominal wall as described previously. A topical hemostatic gelatin sponge or other topical chemical hemostatic agent is laparoscopically applied to the biopsy site on the liver. The patient remains supine after this procedure.

Drainage of Subphrenic and Subhepatic Abscesses

Abscesses in and around the liver may be caused by a variety of microorganisms or as a result of secondary infections from abdominal organs. In general, these abscesses are treated by incision and drainage. A catheter may be introduced into the abscess cavity, which has been localized on a CT scan. The location of the abscess determines the percutaneous approach (i.e., transpleural, subpleural, transperitoneal, or retroperitoneal). Care must be taken to avoid contamination of the pleural or peritoneal cavity.

Intraoperative Hepatic Ultrasound

Intraoperative ultrasound can be used to identify anatomic structures or liver densities associated with a primary tumor or metastasis. Before rotating the liver forward and excising diseased or injured lobes or segments, it is necessary to divide the appropriate ligamentous attachments and to ligate the veins and arteries. Lesions not accessible for resection may be treated with cryosurgery or a Cavitron ultrasonic aspirator. These techniques may also be used in conjunction with resection. An ultrasonic aspirator permits the precise removal of tissue and controls bleeding during resection.

Hepatic Resection

The standard anatomic resections of the liver are right or left lobectomy, right or left trisegmentectomy, and left lateral segmentectomy. Because it is a vital organ, the entire liver cannot be removed without liver transplantation. Lobectomy or segmental resection is indicated for cysts, benign or malignant tumors, or severe penetrating or blunt trauma. Depending on the location of the lesion to be resected, a right or bilateral subcostal incision or an upper midline incision is made and can be extended as needed for exposure and exploration. The liver is the most commonly injured abdominal organ. Hepatic parenchymal injuries usually cause intraperitoneal hemorrhage and shock.

Liver tissue is very friable. The prevention or arrest of hemorrhage is a prime concern. Omental flaps, falciform ligament, or a Gerota fascia flap may be used for coverage and tamponade of bleeding surfaces in conjunction with local hemostatic substances. Microfibrillar collagen or oxidized cellulose is often used to control bleeding. Large, blunt, noncutting needles are used to suture the liver. Drains are usually placed in the wound and brought out through stab wounds. Equipment for blood replacement, portal pressure measurement, and chest drainage should be available.

Portosystemic Shunts

Portal hypertension, bleeding esophageal varices, or massive gastrointestinal hemorrhage may necessitate an emergency surgical procedure for decompression of the portal venous system. Often the patient is alcoholic, with cirrhosis, poor nutrition, and unstable blood volume, or generally is a poor surgical risk. A portosystemic shunt is a vascular anastomosis between the portal and systemic venous systems. The surgeon may select one of several techniques for a portacaval or mesocaval shunt. In patients with portal hypertension and hypersplenism, a splenorenal shunt may be performed in conjunction with a splenectomy for portal decompression.

Splenic Procedures

The highly vascular spleen is located in the upper left abdominal cavity and lies beneath the dome of the diaphragm; it is protected by the lower portion of the ribcage. The capsule of the spleen is covered with peritoneum and is held in place by numerous suspensory ligaments. The splenic artery furnishes the arterial blood supply, and the splenic vein drains into the portal system.

As the largest lymphatic organ of the body, the spleen has an intimate role in the immunologic defenses of the body and acts as a blood reservoir. The main functions of the spleen involve the formation of blood elements. Radionuclide scanning and other radiographic studies provide information for analysis.

Splenectomy

The most common reason for removal of the spleen is hypersplenism—overactivity that causes a reduction in the circulating quantity of red cells, white cells, platelets, or a combination of them. Splenectomies are often scheduled at specific times because patients often require the administration of whole blood immediately before a surgical procedure. Often these patients are also receiving steroid treatment, and provisions are made to maintain therapy during the surgical procedure and postoperatively.

Hematologic disorders, tumors, or accessory spleens may also necessitate surgical intervention. A splenic rupture requires an immediate surgical procedure to prevent fatal hemorrhage and may require a splenectomy. In certain patients with benign disease, a laparoscopic approach has been successfully used for splenectomy.

In performing a splenectomy, a left rectus paramedian, midline, or subcostal incision is used to enter the peritoneal cavity, and the spleen is displaced medially by careful manual manipulation. The splenorenal, splenocolic, and gastrosplenic ligaments are ligated and divided. Great care should be exercised in ligating the splenic artery and vein because these vessels are often friable. Hemorrhage is the principal intraoperative hazard. After removal of the spleen and before closure, careful inspection for bleeding from the splenic pedicle and retroperitoneal space is essential.

Splenorrhaphy

After a splenectomy, patients—especially children—are immunologically impaired (i.e., more susceptible to infection), which sometimes can produce catastrophic results. To protect the patient’s immune competence, surgeons attempt to salvage splenic tissue after splenic trauma. Splenorrhaphy, or splenic repair, can be accomplished in several ways. Once the spleen is mobilized, actively bleeding vessels are ligated and devitalized tissues are debrided. The spleen can then be sutured or stapled along the edge of a partial splenectomy. Microfibrillar collagen or absorbable gelatin sponges can be placed over a small laceration or capsular tear to effect hemostasis. The splenic artery may be ligated.

The spleen may be wrapped in omentum or synthetic mesh. Segments can be reimplanted into an omental pouch in the intraperitoneal space to preserve splenic function. In patients with extensive trauma, a drain that is exteriorized through a stab wound may be inserted into the left subdiaphragmatic space.

Pancreatic Procedures

The pancreas is both an endocrine gland and an exocrine gland. The islets of Langerhans form the endocrine division and secrete the hormones insulin and glucagon, both of which are essential to the metabolism of carbohydrates and the storage of calories. Acini and the ducts leading from them constitute the exocrine portion, which secretes pancreatic juice into the duodenum. Pancreatic juice neutralizes stomach acid; the loss of pancreatic juice results in severe impairment in the digestion and absorption of food.

The pancreas lies transversely across the posterior wall of the upper abdomen behind the stomach. The head, or right extremity of the pancreas, is attached to the duodenum; the tail, or left extremity of the pancreas, is in proximity to the spleen.

Disorders of the pancreas generally include acute and chronic inflammation, cysts, and tumors. The head of the pancreas is the most common site of a malignant pancreatic tumor..2 Cancer in the body or tail of the pancreas is often asymptomatic until advanced and beyond surgical resection. Malignancies are more common in males than females. It is rare before the age of 45 years and is most common after the age of 60.2 Accuracy in the diagnosis of pancreatic problems is difficult, but evaluation by ultrasonography, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), and scanning has led to significant improvements in planning surgical treatment.

An exploratory laparotomy is the most reliable means of diagnosing and evaluating pancreatic trauma. Pancreatitis is associated most often with pancreatic duct stones, gallstones, or alcoholism. Corrective biliary tract procedures usually alleviate gallstone pancreatitis.

Pancreaticojejunostomy

Pancreaticojejunostomy may be performed for relief of pain associated with chronic alcoholic pancreatitis and pseudocysts of the pancreas. There are several types of procedures for the drainage of obstructed ducts or pseudocysts. These methods involve anastomosing a loop of the jejunum (Roux-en-Y loop) to the pancreatic duct. Hemorrhage and leakage of bile are complications to be avoided.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple Procedure)

Pancreaticoduodenectomy is an extensive procedure performed on patients with carcinoma of the head of the pancreas or the ampulla of Vater. A gastrointestinal setup is used for this procedure. The abdominal cavity is exposed through one of several possible anterior incisions, but a long right paramedian incision is usually made. The abdominal and pelvic cavities are explored for distant metastases. Because many vital structures and organs are involved in resecting the diseased proximal portion of the pancreas, careful dissection of vessels is necessary to prevent hemorrhage, which complicates the procedure. Resection includes the distal stomach, the duodenum distal to the pylorus, the distal end of the common bile duct, and all but the tail of the pancreas.

Several methods of reconstructing the digestive tract are possible, but all include anastomosis of the pancreatic duct, common bile duct, stomach, and jejunum. Most surgeons reestablish biliary-intestinal continuity by end-to-side choledochojejunostomy (Fig. 33-15). The stomach and pylorus may be preserved in patients with benign disease or localized, small tumors. After pancreatic and biliary reconstruction, the divided end of the duodenum is anastomosed to the side of the jejunal limb used for the reconstruction. A watertight seal of all anastomoses is essential to prevent peritonitis or pancreatitis. Drains are inserted.

Improvements in preoperative and postoperative care and the refinement of technical details have increased the survival rate of patients who undergo this potentially hazardous radical surgical procedure. The most common postoperative complications of pancreaticoduodenectomy are shock, hemorrhage, renal failure, and pancreatic or biliary fistula. If a fistula should occur, wound suction is continued until the fistula closes. In general, the fistula will close spontaneously if adequate nutrition and electrolyte balance are maintained.

Pancreatectomy

Subtotal distal pancreatectomy is usually performed to resect a benign tumor or for chronic pancreatitis. The distal tail is resected to the head of the pancreas. A splenectomy is usually performed with this procedure because the blood supply to the tail of the pancreas comes from splenic vessels that are sacrificed. A total pancreatectomy allows a wide resection of a primary malignant tumor and its multifocal sites in the pancreas. A patient who has undergone a total pancreatectomy will have endocrine and pancreatic insufficiency.

Pancreaticoduodenal Trauma

Combined injuries of the pancreas and duodenum from penetrating wounds or blunt trauma are among the most complicated to treat. A midline incision is used to explore the abdomen. Suturing to control bleeding, debridement of devitalized tissue, and draining are the initial therapies. Pancreatic fistulas and abscesses are potential complications. Extensive injury of the head of the pancreas and duodenum may require pancreaticoduodenal resection with gastrojejunostomy.

Esophageal Procedures

The esophagus is the 25- to 30-cm-long musculomembranous tube between the pharynx in the throat and the stomach in the abdomen. It is composed distally of striated skeletal muscle and proximally of smooth muscle. It passes through the thoracic cavity and enters the abdominal cavity through the esophageal hiatus (opening) in the right crus of the diaphragm; it joins the right medial surface of the stomach. The esophagus propels food by peristalsis. Within the abdominal cavity, the esophagus is bordered by the liver anteriorly and the aorta posteriorly and slightly to the left (with the spleen on the left), and between the right and left branches of the vagus nerve. The blood supply is derived from the inferior thyroid arteries and the bronchial, gastric, and phrenic branches directly off the aorta.

Patients with long-standing (more than 5 years) gastroesophageal reflux with erosive esophagitis can develop Barrett’s esophagus.3 This can happen when the cellular structure at the gastroesophageal junction has changed from squamous cells to columnar cells. It is more common in males than females and starts between the ages of 40 and 60 years. Studies show there has been an increase in males younger than 40 years with the disease.3

Although there is no cure, further damage can be prevented with appropriate medical treatment. If strictures form, frequent dilation with bougie (pronounced boogee) instrumentation may be necessary. The bougies range in size from 16 to 60 French. The risk for developing cancer is between 5% and 10%, and patients with Barrett’s esophagus are frequently assessed and screened by esophagoscopy and biopsy.

Surgical options include antireflux surgery (hiatal hernia repair), endoscopic ablation (with laser, radiofrequency, or cryosurgery), endoscopic mucosal resection, or esophagectomy.3-5

Diverticula (pouches or pockets) can be present at the distal end of the esophagus near the dorsal aspect of the throat at the level of C5-C6. These pockets can herniate and collect food and can progressively become larger. These pockets are referred to as Zenker’s diverticula, which account for 65% of all diverticula in the esophagus. They can become infected and necrotic or engorged to the point of rupture, which then becomes a surgical emergency. Some texts refer to a herniated diverticula as Killian’s dehiscence.

Esophageal Hiatal Herniorrhaphy

When intraabdominal pressure exceeds pressure in the chest, the abdominal esophagus and a portion of the stomach may slide through the esophageal hiatus and into the thoracic cavity. Although this condition (referred to as hiatal or diaphragmatic hernia) is quite common, a surgical procedure is indicated when the resultant esophagitis causes ulceration, bleeding, stenosis, or chest and back symptoms.4,5 Reflux esophagitis and sphincter incompetence also may have other causes that necessitate a surgical procedure.

The abdominal approach to correct the problem involves a midline or left subcostal incision. Because visualization of the hiatal area may be difficult, the incision may be extended over the lower ribcage. The patient may be placed in a slight reverse Trendelenburg’s position. Organs and vital structures should be protected with moist sponges and gently retracted to expose the hiatus. Long-handled clamps are needed. After mobilization, the hiatus is narrowed with heavy sutures, and the fundus of the stomach is anchored against the diaphragm to prevent recurrent herniation and gastroesophageal reflux.

Prevention of reflux is one of the prime objectives of fundoplication because it was the cause of the patient’s previous esophagitis. Lengthening the intraabdominal esophagus and increasing pressure on the lower esophageal sphincter also help control reflux. The esophagus is secured by wrapping the proximal stomach (fundus) around the gastroesophageal junction in one of two ways: either by a total 360º wrap (Nissen fundoplication) or by a 180º to 200º wrap (Toupet partial fundoplication) (Fig. 33-16). The fundus of the stomach acts as a flap valve to create pressure around the distal esophagus, thus decreasing reflux. As an alternative to fundoplication, some surgeons insert an antireflux collar-like prosthesis around the esophagus just above the gastroesophageal junction.4,5

A laparoscopic fundoplication, which may be performed in select patients, has similar advantages to laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The procedure involves mobilizing the esophagogastric junction and repairing the hiatal defect with a continuous suture technique.4,5 This is followed by a total fundoplication to fix the anterior margin of the diaphragmatic hiatus proximally and the esophagogastric junction distally. The laparoscopic approach has been successful in treating gastroesophageal reflux as a minimally invasive procedure.

Esophagogastrectomy

Removal of the lower portion of the esophagus and proximal stomach may be indicated to resect malignant tumors, benign strictures, or perforations at or near the esophagogastric junction. A left thoracoabdominal or upper midline incision is made. After the esophagus and stomach are mobilized and divided, an end-to-end esophagogastric anastomosis may be completed with staples and/or sutures. An end-to-side anastomosis with plication of the stomach around the distal part of the esophagus may be preferred. Depending on the extent of esophageal resection, other options for restoring continuity of the alimentary tract may be necessary.

Surgical Procedures for Esophageal Varices

Esophageal varices are tortuous, dilated veins in the submucosa of the lower esophagus that may extend up into the esophagus or down into the stomach. This condition is caused by portal hypertension and is usually associated with obstruction within a cirrhotic liver. The rupture of esophageal varices can cause massive hemorrhage. The patient may come to the OR with a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube in place to control bleeding by the use of pressure from the inflated balloon in the tube. A nasogastric tube may be inserted through the central lumen to drain stomach contents and blood.

During the surgical procedure, varices may be sclerosed through an esophagoscope. A sclerosant is injected via a needle puncture into each varix. Several injections may be necessary to achieve complete hemostasis.

Sclerotherapy is usually attempted before more radical procedures are performed. The lower esophagus may be transected and the distal segment anastomosed with a circular stapler just proximal to the stomach. A portosystemic shunt procedure may be performed for portal decompression.

Gastrointestinal Surgery

Advances in the surgical management of patients with gastrointestinal problems have lessened the mortality rate. Interference with the gastrointestinal tract affects its functioning; specific deficiencies may result from gastrointestinal surgery depending on the site and extent of the surgical procedure.

Massive resection of the small intestine can produce long-term nutritional problems such as weight loss and malabsorption of most nutrients. Metabolic bone disease may follow gastric surgery because of poor absorption of calcium and vitamin D. Patients who have undergone extensive gastrointestinal procedures should have a periodic nutritional evaluation. Biochemical tests monitor nutritional status and include serum proteins, albumin-globulin ratio, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN). Body weight is also significant. If caloric intake is inadequate, protein is converted to carbohydrates for energy, and as a result, protein synthesis suffers.

Considerations for Gastrointestinal Surgery

The separation of instruments used for resection and anastomosis and for abdominal closure is a matter of preference of the surgeon and institution. Two distinct setups may be used, but the single setup is most commonly used. The single setup consists of identifying and using only selected instruments and supplies for resection, anastomosis, and abdominal closure and discarding contaminated instruments and equipment from the field after use. Acid secretions from the gastric resection site are very irritating and may cause peritonitis. In addition, the intestinal tract harbors many microorganisms. Leakage into the peritoneal cavity can be a source of generalized peritoneal sepsis. Gloves should be changed after anastomosis is completed; gowns also may be changed.

A nasogastric tube is often inserted for the aspiration of gastric contents or for decompression of the intestinal tract. A variety of gastrointestinal tubes should be available for aspiration and irrigation.

Normal saline solution, not sterile water, should be used in abdominal procedures to moisten laparotomy sponges. Normal saline is an isotonic solution and has the same osmotic quality as blood serum and interstitial fluid. It will not alter sodium, chloride, or fluid balance because it does not cross cell membranes. (Hypotonic solutions cause cells to swell; hypertonic solutions cause them to shrink.) Normal saline is used for intraperitoneal irrigation unless the surgeon prefers to use a solution such as Ringer’s lactate. Antibiotic solutions also may be needed for irrigation.

ESUs are used routinely by many surgeons for electrocoagulation of bleeding vessels in the abdominal wall, omentum, and mesentery. Ligating clips or suture ligatures are used for large vessels. To reduce tissue trauma, the jaws of intestinal forceps should be protected with soft covers made of rubber or fabric.

Stapling devices are preferred by most surgeons for mechanical organ anastomosis. An intraluminal circular stapler can be used for end-to-end, end-to-side, or side-to-side anastomoses from the esophagus to the rectum. A straight linear stapler may be preferred for some gastrointestinal anastomoses and resections. Because the size of the lumen varies in different organs of the gastrointestinal tract, the circulating nurse should not open a sterile disposable stapler until the surgeon determines the appropriate head size or cartridge length for the instrument to be used.

The technical principles that guide the surgeon for all gastrointestinal anastomoses include:

• Good blood supply

• No tension

• Adequate lumen

• Watertight and leak proof

• No distal obstruction

A hand-sutured anastomosis produces an inverted suture line with serosa-to-serosa approximation. Many surgeons prefer anastomosing the inner seromuscular layer with absorbable interrupted or continuous sutures and the outer layers with either absorbable or nonabsorbable interrupted stitches.

A stapled anastomosis results in anastomosed mucosa-to-mucosa apposition.

Gastric Procedures

The stomach, a hollow muscular organ, is situated in the upper left abdomen between the esophagus and duodenum (see Fig. 33-20). Anatomically, it is divided into the fundus, body, and pyloric antrum. The two borders of the stomach, the lesser and greater curvatures, are important surgically because of their relation to the major vascular and lymphatic systems that supply the stomach.

The blood supply is derived from the celiac axis. The gastroduodenal artery and the right and left gastric arteries are the main tributaries. The splenic artery gives rise to the gastroepiploic arteries that are located at the greater curvature. The venous drainage follows the arterial supply but empties into the portal circulation of the liver.

The lymphatics empty into the pancreaticosplenic nodes and into the cisterna chyli via the celiac group. Omentum, a double fold of peritoneum attached to the lesser and greater curvatures, loosely covers the stomach and small intestine.

The innervation is both sympathetic and parasympathetic. The vagus nerve controls the reflex activities of movement and the secretions of the alimentary canal and is significant in rhythmic relaxation of the pyloric sphincter.

Food entering the stomach is reduced to chyme, a semiliquid, and then passes through the duodenum and small intestine. The chyme is absorbed through the lacteals of the intestine into the lymphatics, where it is converted to a milky white chyle. The chyle flows into the cisterna chyli and into the thoracic duct.

The main functions of the stomach are motor, secretory, and endocrine. The motor aspect moves the food along. The secretory actions cause the food to break down. The endocrine component is responsible for the release of gastrin and somatostatin. Gastrin causes the release of acid, and somatostatin inhibits the release of gastrin.

The interference of gastric motor activity or muscular contractions results in gastrointestinal complaints of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, hemorrhage, and dyspepsia. Some diseases, such as cancer, may not produce symptoms until the condition is far advanced. A surgical procedure is indicated when the presence of disease is established after laboratory tests such as gastric analysis, gastroscopy, and/or x-ray studies.

After gastric surgery, dumping syndrome may be experienced by patients shortly after eating. This complication occurs when food and fluids empty rapidly into the jejunum. It is characterized by nausea, vomiting, weakness, dizziness, pallor, sweating, palpitations, and diarrhea. Dumping syndrome after eating may persist for 6 months to 1 year postoperatively.

Gastroscopy

Gastroscopy involves the passage of a flexible fiberoptic gastroscope. This procedure is usually performed while the patient is sedated, with a topical anesthetic applied in the oropharynx to control the gag reflex. The operator visually inspects the mucosal walls of the stomach, and tissue specimens are sometimes obtained. Bleeding points may be coagulated with a laser, ESU, or a sclerosing agent.

Gastrostomy

Establishment of a temporary or permanent opening in the stomach may be indicated for gastrointestinal decompression or to provide alimentation for a prolonged period when nutrition cannot be maintained by other means. A gastrostomy tube eliminates the incidence of aspiration that may occur around a nasogastric tube. Often the patient is too debilitated to tolerate a major surgical procedure or may have an inoperable esophageal tumor or oropharyngeal trauma. A Foley, Malecot, Pezzer, or mushroom catheter may be inserted percutaneously into the stomach.

Simple Gastrostomy

With the patient under general anesthesia, the stomach is exposed through a small upper left abdominal or midline incision. The catheter is inserted into the anterior gastric wall and is held in place with pursestring sutures; it is brought out through a separate stab wound in the left upper quadrant. The stomach is sutured to the abdominal wall at the exit site of the catheter. After an abdominal procedure on a critically ill patient, the surgeon may prefer to place a small-bore catheter into the jejunum rather than the stomach for enteral hyperalimentation.

Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy

With percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, the patient is placed under IV sedation and an endoscopist introduces a fiberoptic gastroscope and insufflates the stomach with air to create a working space and a turgid surface to the stomach. Light from the scope is directed anteriorly for transillumination through the abdominal wall. The surgeon infiltrates the skin with a local anesthetic at a selected gastrostomy site, usually approximately one third of the distance along the left costal margin at the midclavicular line. The gastrostomy tube is introduced through a percutaneous puncture and secured with sutures.

Gastric Resections

The stomach may be totally or partially resected for removal of a malignant tumor or for benign chronic ulcer disease. Although surgical resection is the only cure, gastric carcinomas are often inoperable because of metastases to the liver or extension into surrounding tissues. In such cases, palliative procedures may be performed. The appropriate procedure is determined after thorough exploration of the abdominal cavity by the surgeon. Circular staplers are commonly used for anastomosis after resection. Leakage at the site of anastomosis leads to peritonitis. Some surgeons oversew the staple line.

Total Gastrectomy

With a total gastrectomy, the entire stomach is excised for malignant lesions through a bilateral subcostal, long transrectus, or thoracoabdominal incision. A total gastrectomy necessitates reconstruction of esophagointestinal continuity by establishing an anastomosis between a loop of jejunum and the esophagus. This anastomosis may be end-to-side with a lateral jejunojejunostomy or end-to-end with a Roux-en-Y jejunojejunostomy. The purpose of the jejunojejunostomy is to prevent the reflux of bile and pancreatic fluids into the esophagus. Some surgeons create a jejunal pouch for this purpose.

Subtotal Gastrectomy

Partial resections of the stomach, originally described by Theodor Billroth (1829-1894), are often referred to as Billroth procedures. A benign lesion (usually an ulcer) or a malignant lesion located in the pyloric half of the stomach requires removal of the lower half to two thirds of the stomach. In a patient with a gastric or duodenal ulcer, a partial resection limits gastric acidity and relieves pain, bleeding, vomiting, and weight loss.

In this procedure, the peritoneal cavity is entered through a right paramedian or upper midline abdominal incision. A variety of surgical procedures may be used to reestablish gastrointestinal continuity. Anastomosis of the remaining portion of the stomach to the duodenum (gastroduodenostomy, antrectomy, or Billroth I, Fig. 33-17) or to a loop of the jejunum (gastrojejunostomy, or Billroth II, Fig. 33-18) is often performed. A truncal vagotomy, which is discussed in the following section, is performed to eliminate the possibility of postoperative peptic ulceration.

Common modifications of the Billroth I procedure are the Schoemaker and von Haberer-Finney techniques. The Schoemaker procedure involves end-to-end anastomosis of the stomach and duodenum after the lesser curvature of the stomach is sutured to make the anastomosis site the same size as the duodenum. With the von Haberer-Finney method, the lateral wall of the duodenum is brought up to the stomach so that the entire end of the stomach is open for direct anastomosis.

Popular modifications of the Billroth II procedure include the Polya and Hofmeister techniques, both of which involve variations of end-to-side gastrojejunostomy.

Vagotomy

Chronic gastric, pyloric, and duodenal ulcers that do not respond to medical treatment cause patients severe pain and difficulty in eating and sleeping. Vagotomy, the division of the vagus nerves, may be recommended to interrupt vagal nerve impulses, thus lowering the production of gastric hydrochloric acid and hastening gastric emptying. Vagotomy can be performed at several different locations along the course of the vagus nerve (Fig. 33-19).

Proximal gastric vagotomy, also known as parietal cell vagotomy, divides the vagal nerve fibers to the proximal stomach but maintains the entire stomach and vagal nerves to the antrum. These sections of the vagal nerve inhibit the release of gastrin, a stimulant of gastric secretion.

Truncal vagotomy and selective vagotomy require a concomitant drainage procedure because these procedures denervate the stomach. A gastroenterostomy is performed with a truncal vagotomy, which divides the vagal trunks at the distal esophagus. An antrectomy is performed with a selective vagotomy, which transects the gastric branches. Vagotomy with drainage is a compromise procedure and is restricted to high-risk patients or those with severe duodenal deformity.

Pyloroplasty, enlarging the pyloric opening between the stomach and duodenum, may be performed in patients with an obstructing pyloric ulcer or in conjunction with vagotomy to treat bleeding duodenal ulcers. Duodenal dilation or duodenoplasty may be indicated.

Vagotomy procedures, which are conservative surgical therapies compared with gastrectomy, decrease the surgical risk for select patients with chronic ulcers. It is now known that ulcers caused by the Helicobacter pylori organism can be cured with antibiotics.

Gastrojejunostomy (Roux-en-Y Gastroenterostomy)

A procedure may be necessary to reestablish continuity between the stomach and intestinal tract, such as after a partial gastrectomy or when the lower end of the stomach is obstructed by an ulcer or a nonresectable tumor. A gastrojejunostomy may be performed to treat alkaline reflux gastritis, postgastrectomy syndromes such as postvagotomy diarrhea, and dumping syndromes. Except in geriatric patients, a concomitant vagotomy is necessary to prevent a postoperative gastrojejunal ulcer when the acid-forming portion of the stomach is not resected.

In this procedure, a loop of jejunum may be anastomosed to either the anterior or the posterior wall of the stomach; both approaches have advantages and disadvantages. In a Roux-en-Y gastrojejunostomy, the jejunum is divided. The distal end is anastomosed to the side of the stomach, and the proximal end is anastomosed to the side of the jejunum at a lower level. The result is a Y-shaped double anastomosis that diverts the flow of bile and pancreatic enzymes directly into the jejunum, bypassing the created gastric stoma.

An adaptation of a Roux-en-Y anastomosis is also used to drain the biliary tract or other organs, such as the pancreas or esophagus, directly into the jejunum to bypass the stomach and prevent the reflux of intestinal contents.

Bariatric Surgery

The study of morbid obesity, or bariatrics, has led to the development of a subspecialization in general surgery: bariatric surgery. AORN has published guidelines for the safe care of patients undergoing bariatric procedures.

Bariatric surgery can be performed as an open abdominal surgery or as a laparoscopic procedure. The surgical landmarks are altered in obese patients because the body habitus is large and extends beyond the borders of the average-sized patient. Insufflation via Veress needle may not be performed at the umbilicus. An alternative site is Palmer’s Point, because the risk of injury is less (Fig. 33-20) The umbilicus, for example, lies several inches lower on a pendulous abdomen. Using the infraumbilical or supraumbilical area of the patient as an inflation or primary trocar site could cause injury to nontarget organs (Fig. 33-21).6-8

Bariatric procedures produce three types of results:

1. Restricted intake caused by an inflatable Silastic band (Fig. 33-22)

2. Bypass the food and decrease absorption (Fig. 33-23)

3. Bypass absorption and restrict intake

People who have a body mass index (BMI) of 40 or more, weigh 100 pounds (45.4 kg) more than their ideal weight, and who have failed to lose weight despite years of medical treatment are potential candidates for bariatric surgery.6,7 Patients with a BMI of 35 to 40 and have serious comorbid disease, such as obstructive sleep apnea, cardiomyopathy, and type 2 diabetes, may be candidates after careful screening.6,7 The plan of care requires the patient to have psychologic and physiologic support during the process, or the procedure could be a failure. Some facilities have extended the procedure to obese adolescents aged 15 years and older, with varying degrees of success.

The physical size of a patient who is obese presents special needs with respect to transporting and positioning, selecting instrumentation, and providing psychologic and physiologic support. The OR bed must support the patient’s weight and fit the length and width of the patient’s body habitus. The standard OR bed cannot do these things safely, so a specialized OR bed must be used.

Many morbidly obese patients have medical complications such as hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, cardiac disease, degenerative arthritis, gallbladder disease, or diabetes mellitus. Consideration is given to pressure-reducing surfaces, such as gel pads and positioning devices designed to hold large limbs.

The plan of care for obese patients usually includes the application of antiembolic stockings and the insertion of a nasogastric tube, a Foley catheter, IV and arterial lines, and central venous pressure (CVP). Because respiratory distress is a potential complication during the induction of anesthesia, intubation while the patient is awake may be the technique of choice. Many obese patients have short, wide necks, so positioning head support in a “sniffing posture” may be necessary to establish a secure airway.6

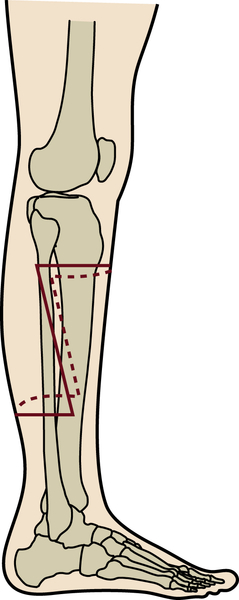

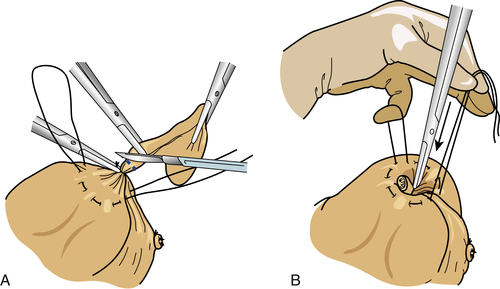

• FIG. 33-21 Laparoscopic ports for a bariatric procedure. Note the displacement of the umbilical landmark.