Normal Labor and Delivery

Sarah Kilpatrick, Etoi Garrison

Key Abbreviations

Overview

The initiation of normal labor at term requires endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine signaling between the fetus, uterus, placenta, and the mother. Although the exact trigger for human labor at term remains unknown, it is believed to involve conversion of fetal dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) to estriol and estradiol by the placenta. These hormones upregulate transcription of progesterone, progesterone receptors, oxytocin receptors, and gap junction proteins within the uterus, which helps to facilitate regular uterine contractions. The latent phase of labor is characterized by a slower rate of cervical dilation, whereas the active phase of labor is characterized by a faster rate of cervical dilation and does not begin for most women until the cervix is dilated 6 cm. The duration of the second stage of labor can be affected by a number of factors including epidural use, fetal position, fetal weight, ethnicity, and parity. This chapter will review the characteristics and physiology of normal labor at term. Factors that affect the average duration of the first and second stage of labor progress will be reviewed, and an evidence-based evaluation of strategies to support the mother during labor and facilitate safe delivery of the fetus will be presented.

Labor: Definition and Physiology

Labor is defined as the process by which the fetus is expelled from the uterus. More specifically, labor requires regular, effective contractions that lead to dilation and effacement of the cervix. This chapter describes the physiology and normal characteristics of term labor and delivery.

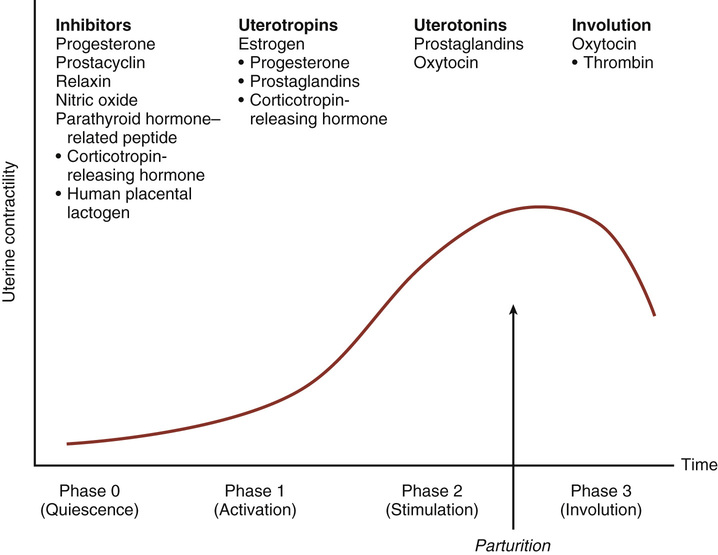

The physiology of labor initiation has not been completely elucidated, but the putative mechanisms have been well reviewed by Liao and colleagues.1 Labor initiation is species specific, and the mechanisms of human labor are unique. The four phases of labor from quiescence to involution are outlined in Figure 12-1.2 The first phase is quiescence, which represents that time in utero before labor begins, when uterine activity is suppressed by the action of progesterone, prostacyclin, relaxin, nitric oxide, parathyroid hormone–related peptide, and possibly other hormones. During the activation phase, estrogen begins to facilitate expression of myometrial receptors for prostaglandins (PGs) and oxytocin, which results in ion channel activation and increased gap junctions. This increase in the gap junctions between myometrial cells facilitates effective contractions.3 In essence, the activation phase readies the uterus for the subsequent stimulation phase, when uterotonics—particularly PGs and oxytocin—stimulate regular contractions. In the human, this process at term may be protracted, occurring over days to weeks. The final phase, uterine involution, occurs after delivery and is mediated primarily by oxytocin. The first three phases of labor require endocrine, paracrine, and autocrine interaction between the fetus, membranes, placenta, and mother.

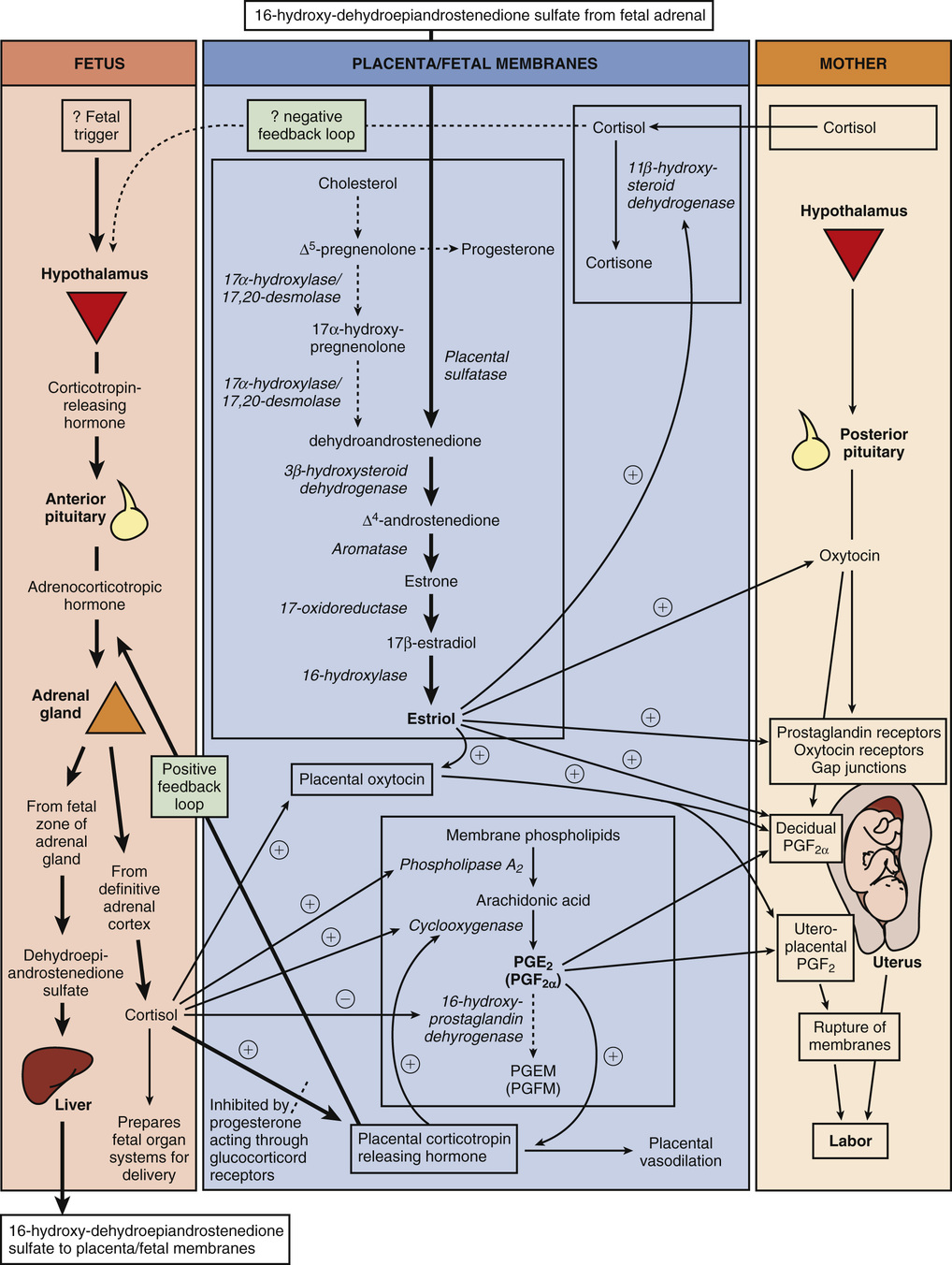

The fetus has a central role in the initiation of term labor in nonhuman mammals; in humans, the fetal role is not completely understood (Fig. 12-2).2-5 In sheep, term labor is initiated through activation of the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, with a resultant increase in fetal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol.4,5 Fetal cortisol increases production of estradiol and decreases production of progesterone by a shift in placental metabolism of cortisol dependent on placental 17α-hydroxylase. The change in the circulating progesterone/estradiol concentration stimulates placental production of oxytocin and PG, particularly PGF2α, which in turn promotes myometrial contractility.4 If this increase in fetal ACTH and cortisol is blocked, progesterone levels remain unchanged, and parturition is delayed.5 In contrast, humans lack placental 17α-hydroxylase, maternal and fetal levels of progesterone remain elevated, and no trigger exists for parturition because of an increase in fetal cortisol near term. Rather, in humans, evidence suggests that placental production of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) near term activates the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary axis and results in increased production of dehydroepiandrostenedione by the fetal adrenal gland.6 Fetal dehydroepiandrostenedione is converted in the placenta to estradiol and estriol. Placenta-derived estriol potentiates uterine activity by enhancing the transcription of maternal (likely decidual) PGF2α, PG receptors, oxytocin receptors, and gap-junction proteins.6-8 In humans, no documented decrease in progesterone has been observed near term, and a fall in progesterone is not necessary for labor initiation. However, some research suggests the possibility of a functional progesterone withdrawal in humans. Labor is accompanied by a decrease in the concentration of progesterone receptors and a change in the ratio of progesterone receptor isoforms A and B in both the myometrium9-11 and the membranes.12 During labor, increased expression of nuclear and membrane progesterone receptor isoforms serve to enhance genomic expression of contraction-associated proteins, increase intracellular calcium, and decrease cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP).13 More research is needed to elucidate the precise mechanism through which the human parturition cascade is activated. Fetal maturation might play an important role as might maternal cues that affect circadian cycling. Most species have distinct diurnal patterns of contractions and delivery, and in humans, the majority of contractions occur at night.2,14

Oxytocin is commonly used for labor induction and augmentation, and a full understanding of the mechanism of oxytocin action is important. Oxytocin is a peptide hormone synthesized in the hypothalamus and released from the posterior pituitary in a pulsatile fashion. At term, oxytocin serves as a potent uterotonic agent capable of stimulating uterine contractions at intravenous (IV) infusion rates of 1 to 2 mIU/min.15 Oxytocin is inactivated largely in the liver and kidney, and during pregnancy, it is degraded primarily by placental oxytocinase. Its biologic half-life is approximately 3 to 4 minutes, but it appears to be shorter when higher doses are infused. Concentrations of oxytocin in the maternal circulation do not change significantly during pregnancy or before the onset of labor, but they do rise late in the second stage of labor.15,16 Studies of fetal pituitary oxytocin production and the umbilical arteriovenous differences in plasma oxytocin strongly suggest that the fetus secretes oxytocin that reaches the maternal side of the placenta.15,17 The calculated rate of active oxytocin secretion from the fetus increases from a baseline of 1 mIU/min before labor to around 3 mIU/min after spontaneous labor.

Significant differences in myometrial oxytocin receptor distribution have been reported, with large numbers of fundal receptors and fewer receptors in the lower uterine segment and cervix.18 Myometrial oxytocin receptors increase on average by 100- to 200-fold during pregnancy and reach a maximum during early labor.15,16,19,20 This rise in receptor concentration is paralleled by an increase in uterine sensitivity to circulating oxytocin. Specific high-affinity oxytocin receptors have also been isolated from human amnion and decidua parietalis but not decidua vera.15,18 It has been suggested that oxytocin plays a dual role in parturition. First, through its receptor, oxytocin directly stimulates uterine contractions. Second, oxytocin may act indirectly by stimulating the amnion and decidua to produce PG.18,21-23 Indeed, even when uterine contractions are adequate, induction of labor at term is successful only when oxytocin infusion is associated with an increase in PGF production.18

Oxytocin binding to its receptor activates phospholipase C.24 In turn, phospholipase C increases intracellular calcium both by stimulating the release of intracellular calcium and by promoting the influx of extracellular calcium. Oxytocin stimulation of phospholipase C can be inhibited by increased levels of cAMP.24 Increased calcium levels stimulate the calmodulin-mediated activation of myosin light-chain kinase. Oxytocin may also stimulate uterine contractions via a calcium-independent pathway by inhibiting myosin phosphatase, which in turn increases myosin phosphorylation. These pathways (of PGF2α and intracellular calcium) have been the target of multiple tocolytic agents: indomethacin, calcium channel blockers, β-mimetics (through stimulation of cAMP), and magnesium.

Mechanics of Labor

Labor and delivery are not passive processes in which uterine contractions push a rigid object through a fixed aperture. The ability of the fetus to successfully negotiate the pelvis during labor and delivery depends on the complex interactions of three variables: uterine activity, the fetus, and the maternal pelvis. This complex relationship has been simplified in the mnemonic powers, passenger, passage.

Uterine Activity (Powers)

The powers refer to the forces generated by the uterine musculature. Uterine activity is characterized by the frequency, amplitude (intensity), and duration of contractions. Assessment of uterine activity may include simple observation, manual palpation, external objective assessment techniques (such as external tocodynamometry), and direct measurement via an intrauterine pressure catheter (IUPC). External tocodynamometry measures the change in shape of the abdominal wall as a function of uterine contractions and, as such, is qualitative rather than quantitative. Although it permits graphic display of uterine activity and allows for accurate correlation of fetal heart rate (FHR) patterns with uterine activity, external tocodynamometry does not allow measurement of contraction intensity or basal intrauterine tone. The most precise method for determination of uterine activity is the direct measurement of intrauterine pressure with an IUPC. However, this procedure should not be performed unless indicated given the small but finite associated risks of uterine perforation, placental disruption, and intrauterine infection.

Despite technologic improvements, the definition of “adequate” uterine activity during labor remains unclear. Classically, three to five contractions in 10 minutes has been used to define adequate labor; this pattern has been observed in approximately 95% of women in spontaneous labor. In labor, patients usually contract every 2 to 5 minutes, with contractions becoming as frequent as every 2 to 3 minutes in late active labor and during the second stage. Abnormal uterine activity can also be observed either spontaneously or as a result of iatrogenic interventions. Tachysystole is defined as more than five contractions in 10 minutes averaged over 30 minutes. If tachysytole occurs, documentation should note the presence or absence of FHR decelerations. The term hyperstimulation should no longer be used.25

Various units of measure have been devised to objectively quantify uterine activity, the most common of which is the Montevideo unit (MVU), a measure of average frequency and amplitude above basal tone (the average strength of contractions in millimeters of mercury multiplied by the number of contractions per 10 min). Although 150 to 350 MVU has been described for adequate labor, 200 to 250 MVU is commonly accepted to define adequate labor in the active phase.26,27 No data identify adequate forces during latent labor. Although it is generally believed that optimal uterine contractions are associated with an increased likelihood of vaginal delivery, data are limited to support this assumption. If uterine contractions are “adequate” to effect vaginal delivery, one of two things will happen: either the cervix will efface and dilate, and the fetal head will descend, or caput succedaneum (scalp edema) and molding of the fetal head (overlapping of the skull bones) will worsen without cervical effacement and dilation. The latter situation suggests the presence of cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD), which can be either absolute, in which the fetus is simply too large to negotiate the pelvis, or relative, in which delivery of the fetus through the pelvis would be possible under optimal conditions but is precluded by malposition or abnormal attitude of the fetal head.

Fetus (Passenger)

The passenger, of course, is the fetus. Several fetal variables influence the course of labor and delivery. Fetal size can be estimated clinically by abdominal palpation or ultrasound or by asking a multiparous patient about her best estimate, but all of these methods are subject to a large degree of error. Fetal macrosomia is defined by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) as birthweight greater than or equal to the 90th percentile for a given gestational age or greater than 4500 g for any gestational age,28 and it is associated with an increased likelihood of planned cesarean delivery, labor dystocia, cesarean delivery after a failed trial of labor, shoulder dystocia, and birth trauma.29 Fetal lie refers to the longitudinal axis of the fetus relative to the longitudinal axis of the uterus. Fetal lie can be longitudinal, transverse, or oblique (Fig. 12-3). In a singleton pregnancy, only fetuses in a longitudinal lie can be safely delivered vaginally.

Presentation refers to the fetal part that directly overlies the pelvic inlet. In a fetus presenting in the longitudinal lie, the presentation can be cephalic (vertex) or breech. Compound presentation refers to the presence of more than one fetal part overlying the pelvic inlet, such as a fetal hand and the vertex. Funic presentation refers to presentation of the umbilical cord and is rare at term. In a cephalic fetus, the presentation is classified according to the leading bony landmark of the skull, which can be either the occiput (vertex), the chin (mentum), or the brow (Fig. 12-4). Malpresentation, a term that refers to any presentation other than vertex, is seen in approximately 5% of all term labors (see Chapter 17).

Attitude refers to the position of the head with regard to the fetal spine (the degree of flexion and/or extension of the fetal head). Flexion of the head is important to facilitate engagement of the head in the maternal pelvis. When the fetal chin is optimally flexed onto the chest, the suboccipitobregmatic diameter (9.5 cm) presents at the pelvic inlet (Fig. 12-5). This is the smallest possible presenting diameter in the cephalic presentation. As the head deflexes (extends), the diameter presenting to the pelvic inlet progressively increases even before the malpresentations of brow and face are encountered (see Fig. 12-5) and may contribute to failure to progress in labor. The architecture of the pelvic floor along with increased uterine activity may correct deflexion in the early stages of labor.

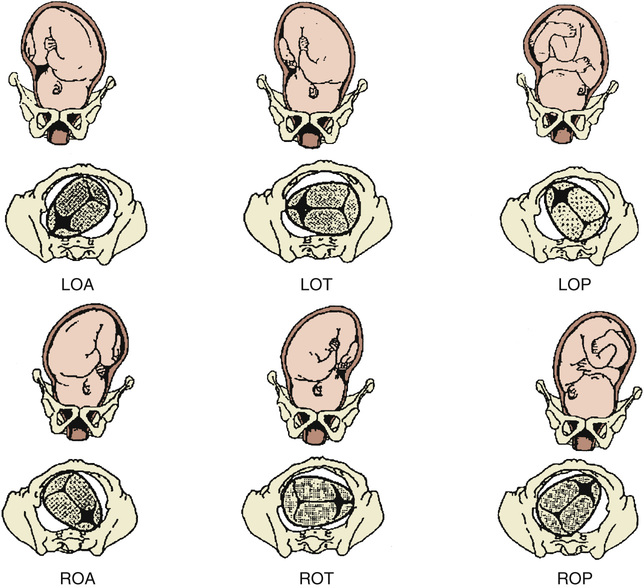

Position of the fetus refers to the relationship of the fetal presenting part to the maternal pelvis, and it can be assessed most accurately on vaginal examination. For cephalic presentations, the fetal occiput is the reference: if the occiput is directly anterior, the position is occiput anterior (OA); if the occiput is turned toward the mother's right side, the position is right occiput anterior (ROA). In the breech presentation, the sacrum is the reference (right sacrum anterior). The various positions of a cephalic presentation are illustrated in Figure 12-6. In a vertex presentation, position can be determined by palpation of the fetal sutures: the sagittal suture is the easiest to palpate, but palpation of the distinctive lambdoid sutures should identify the position of the fetal occiput; the frontal suture can also be used to determine the position of the front of the vertex.

Most commonly, the fetal head enters the pelvis in a transverse position and then, as a normal part of labor, it rotates to an OA position. Most fetuses deliver in the OA, left occiput anterior (LOA), or ROA position. Malposition refers to any position in labor that is not in the above three categories. In the past, fewer than 10% of presentations were occiput posterior (OP) at delivery.30 However, epidural analgesia may be an independent risk factor for persistent OP presentation in labor. In an observational cohort study, OP presentation was observed in 12.9% of women with epidurals compared with 3.3% of controls (P = .002).31 In a Cochrane meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials (RCTs), malposition was 40% more likely for women with an epidural compared with controls; however, this difference was not statistically significant, and more RCTs are needed (odds ratio [OR] 1.40; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.98 to 1.99).32 Asynclitism occurs when the sagittal suture is not directly central relative to the maternal pelvis. If the fetal head is turned such that more parietal bone is present posteriorly, the sagittal suture is more anterior; this is referred to as posterior asynclitism. In contrast, anterior asynclitism occurs more parietal bone presents anteriorly. The occiput transverse (OT) and OP positions are less common at delivery and are more difficult to deliver.

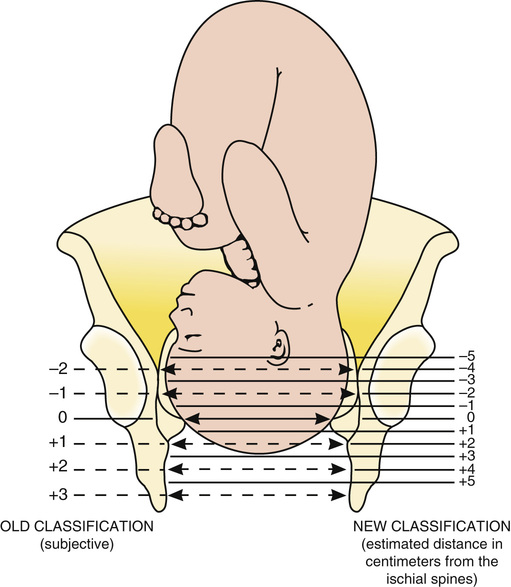

Station is a measure of descent of the bony presenting part of the fetus through the birth canal (Fig. 12-7). The current standard classification (−5 to +5) is based on a quantitative measure in centimeters of the distance of the leading bony edge from the ischial spines. The midpoint (0 station) is defined as the plane of the maternal ischial spines. The ischial spines can be palpated on vaginal examination at approximately 8 o'clock and 4 o'clock. For the right-handed person, they are most easily felt on the maternal right.

An abnormality in any of these fetal variables may affect both the course of labor and the route of delivery. For example, OP presentation is well known to be associated with longer labor, operative vaginal delivery, and an increased risk of cesarean delivery.31,33

Maternal Pelvis (Passage)

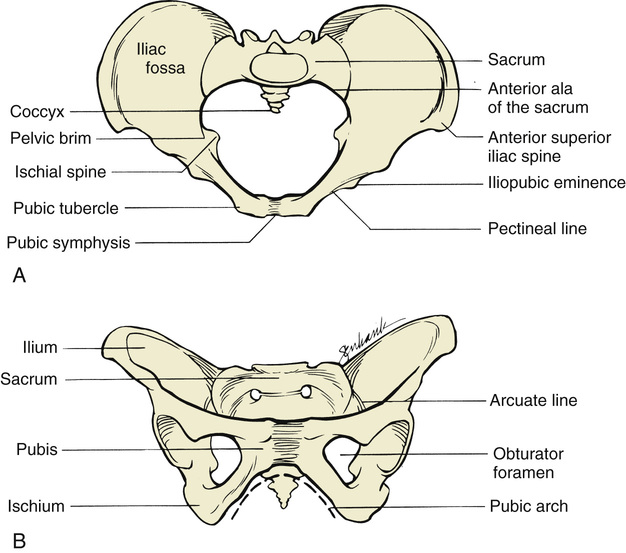

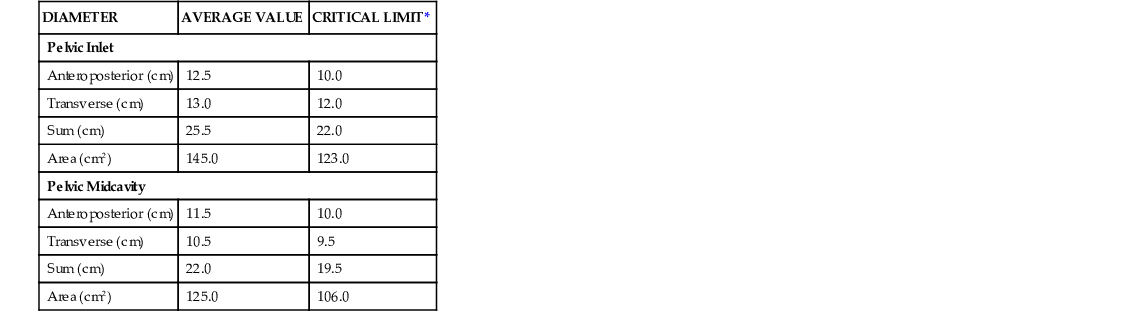

The passage consists of the bony pelvis—composed of the sacrum, ilium, ischium, and pubis—and the resistance provided by the soft tissues. The bony pelvis is divided into the false (greater) and true (lesser) pelvis by the pelvic brim, which is demarcated by the sacral promontory, the anterior ala of the sacrum, the arcuate line of the ilium, the pectineal line of the pubis, and the pubic crest culminating in the symphysis (Fig. 12-8). Measurements of the various parameters of the bony female pelvis have been made with great precision, directly in cadavers and using radiographic imaging in living women. Such measurements have divided the true pelvis into a series of planes that must be negotiated by the fetus during passage through the birth canal, which can be broadly termed the pelvic inlet, midpelvis, and pelvic outlet. Pelvimetry performed with radiographic computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been used to determine average and critical limit values for the various parameters of the bony pelvis (Table 12-1).34,35 Critical limit values are measurements that may be associated with a significant probability of CPD depending upon fetal size and gestational age.34 However, subsequent studies were unable to demonstrate threshold pelvic or fetal cutoff values with sufficient sensitivity or specificity to predict CPD and the subsequent need for cesarean delivery prior to the onset of labor.36,37 In current obstetric practice, radiographic CT and MRI pelvimetry are rarely used given the lack of evidence of benefit and some data that show possible harm (increased incidence of cesarean delivery); instead, a clinical trial of the pelvis (labor) is used. The remaining indications for radiography, CT pelvimetry, or MRI are evaluation for vaginal breech delivery or evaluation of a woman who has suffered a significant pelvic fracture.38

TABLE 12-1

AVERAGE AND CRITICAL LIMIT VALUES FOR PELVIC MEASUREMENTS BY X-RAY PELVIMETRY

| DIAMETER | AVERAGE VALUE | CRITICAL LIMIT* |

| Pelvic Inlet | ||

| Anteroposterior (cm) | 12.5 | 10.0 |

| Transverse (cm) | 13.0 | 12.0 |

| Sum (cm) | 25.5 | 22.0 |

| Area (cm2) | 145.0 | 123.0 |

| Pelvic Midcavity | ||

| Anteroposterior (cm) | 11.5 | 10.0 |

| Transverse (cm) | 10.5 | 9.5 |

| Sum (cm) | 22.0 | 19.5 |

| Area (cm2) | 125.0 | 106.0 |

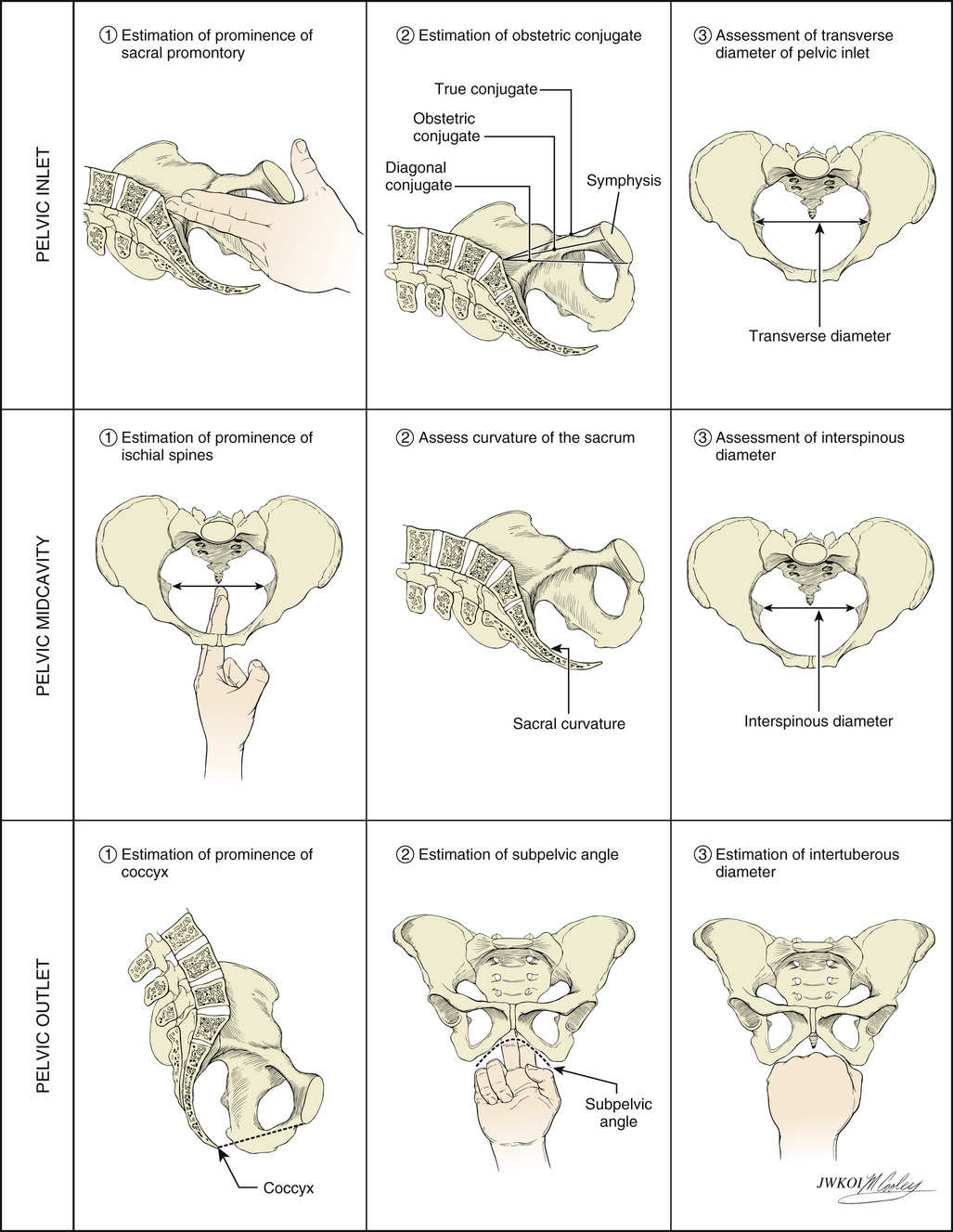

Clinical pelvimetry is currently the only method of assessing the shape and dimensions of the bony pelvis in labor.36 A useful protocol for clinical pelvimetry is detailed in Figure 12-9 and involves assessment of the pelvic inlet, midpelvis, and pelvic outlet. Reported average and critical-limit pelvic diameters may be used as a historical reference during the clinical examination to determine pelvic shape and assess risk for CPD. The inlet of the true pelvis is largest in its transverse diameter and averages 13.5 cm.36 The diagonal conjugate, the distance from the sacral promontory to the inferior margin of the symphysis pubis as assessed on vaginal examination, is a clinical representation of the anteroposterior (AP) diameter of the pelvic inlet. The true conjugate, or obstetric conjugate, of the pelvic inlet is the distance from the sacral promontory to the superior aspect of the symphysis pubis. The obstetric conjugate has an average value of 11 cm and is the smallest diameter of the inlet. It is considered to be contracted if it measures less than 10 cm.36 The obstetric conjugate cannot be measured clinically but can be estimated by subtracting 1.5 to 2.0 cm from the diagonal conjugate, which has an average distance of 12.5 cm.

The limiting factor in the midpelvis is the transverse interspinous diameter (the measurement between the ischial spines), which is usually the smallest diameter of the pelvis but should be greater than 10 cm. The pelvic outlet is rarely of clinical significance, however. The average pubic angle is greater than 90 degrees and will typically accommodate two fingerbreadths.36 The AP diameter from the coccyx to the symphysis pubis is approximately 13 cm in most cases, and the transverse diameter between the ischial tuberosities is approximately 8 cm and will typically accommodate four knuckles (see Fig. 12-9).

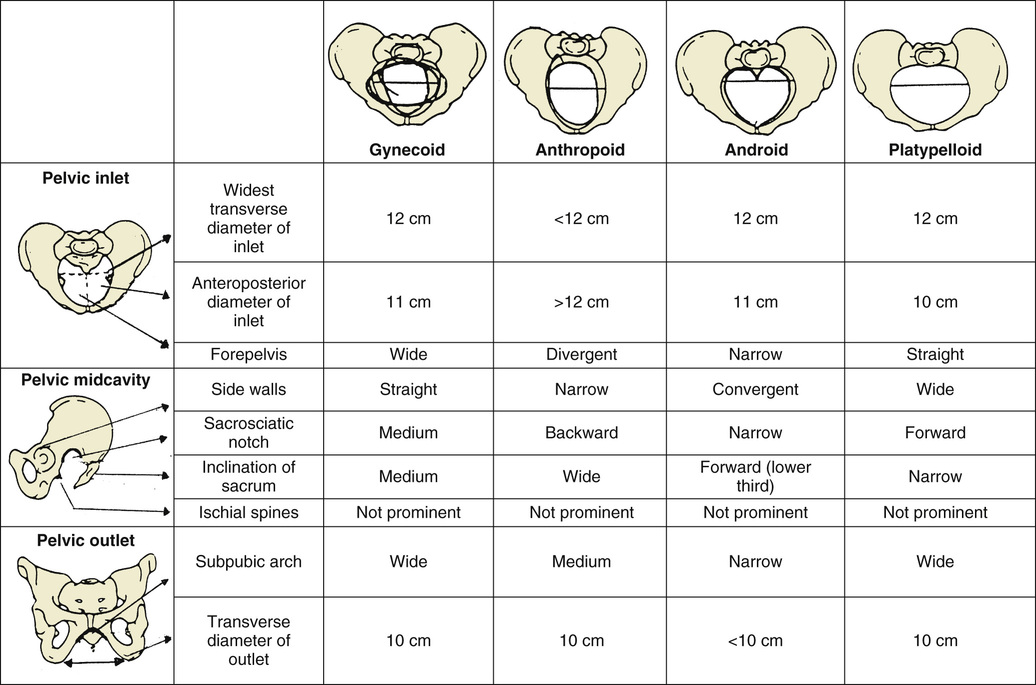

The shape of the female bony pelvis can be classified into four broad categories: gynecoid, anthropoid, android, and platypelloid (Fig. 12-10). This classification is based on the radiographic studies of Caldwell and Moloy39 and separates those with more favorable characteristics (gynecoid, anthropoid) from those less favorable for vaginal delivery (android, platypelloid). In reality, however, many women fall into intermediate classes, and the distinctions become arbitrary. The gynecoid pelvis is the classic female shape. The anthropoid pelvis—with its exaggerated oval shape of the inlet, largest AP diameter, and limited anterior capacity—is more often associated with delivery in the OP position. The android pelvis is male in pattern and theoretically has an increased risk of CPD, and the broad and flat platypelloid pelvis theoretically predisposes to a transverse arrest. Although the assessment of fetal size, along with pelvic shape and capacity, is still of clinical utility, it is a very inexact science. An adequate trial of labor is the only definitive method to determine whether a fetus will be able to safely negotiate through the pelvis.

Pelvic soft tissues may provide resistance in both the first and second stages of labor. In the first stage, resistance is offered primarily by the cervix, whereas in the second stage, it is offered by the muscles of the pelvic floor. In the second stage of labor, the resistance of the pelvic musculature is believed to play an important role in the rotation and movement of the presenting part through the pelvis.

Cardinal Movements in Labor

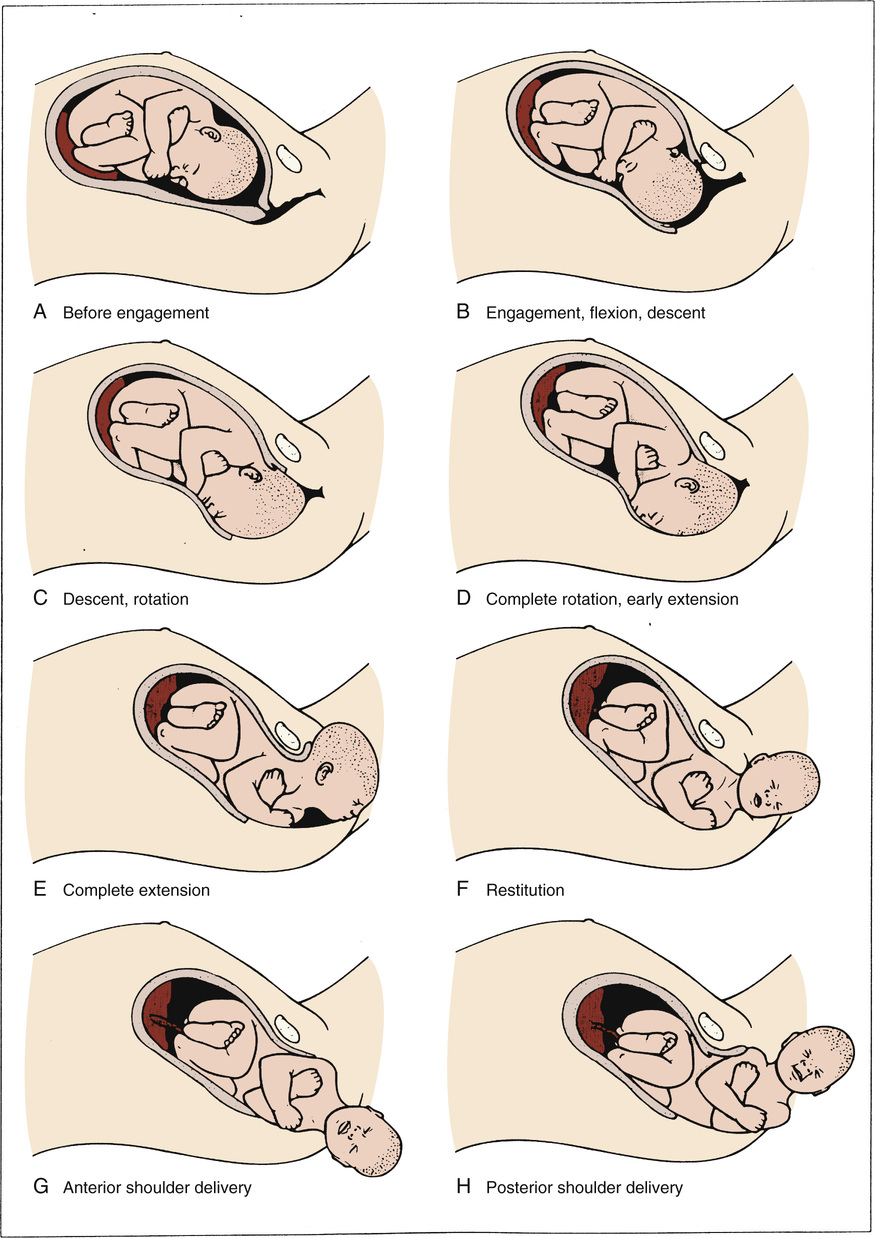

The cardinal movements refer to changes in the position of the fetal head during its passage through the birth canal. Because of the asymmetry of the shape of both the fetal head and the maternal bony pelvis, such rotations are required for the fetus to successfully negotiate the birth canal. Although labor and birth comprise a continuous process, seven discrete cardinal movements are described: (1) engagement, (2) descent, (3) flexion, (4) internal rotation, (5) extension, (6) external rotation or restitution, and (7) expulsion (Fig. 12-11).

Engagement

Engagement refers to passage of the widest diameter of the presenting part to a level below the plane of the pelvic inlet (Fig. 12-12). In the cephalic presentation with a well-flexed head, the largest transverse diameter of the fetal head is the biparietal diameter (9.5 cm). In the breech, the widest diameter is the bitrochanteric diameter. Clinically, engagement can be confirmed by palpation of the presenting part both abdominally and vaginally. With a cephalic presentation, engagement is achieved when the presenting part is at zero station on vaginal examination. Engagement is considered an important clinical prognostic sign because it demonstrates that, at least at the level of the pelvic inlet, the maternal bony pelvis is sufficiently large to allow descent of the fetal head. In nulliparas, engagement of the fetal head usually occurs by 36 weeks' gestation; however, in multiparas engagement can occur later in gestation or even during the course of labor.

Descent

Descent refers to the downward passage of the presenting part through the pelvis. Descent of the fetus is not continuous; the greatest rates of descent occur in the late active phase and during the second stage of labor.

Flexion

Flexion of the fetal head occurs passively as the head descends owing to the shape of the bony pelvis and the resistance offered by the soft tissues of the pelvic floor. Although flexion of the fetal head onto the chest is present to some degree in most fetuses before labor, complete flexion usually occurs only during the course of labor. The result of complete flexion is to present the smallest diameter of the fetal head (the suboccipitobregmatic diameter) for optimal passage through the pelvis.

Internal Rotation

Internal rotation refers to rotation of the presenting part from its original position as it enters the pelvic inlet (usually OT) to the AP position as it passes through the pelvis. As with flexion, internal rotation is a passive movement that results from the shape of the pelvis and the pelvic floor musculature. The pelvic floor musculature, including the coccygeus and ileococcygeus muscles, forms a V-shaped “hammock” that diverges anteriorly. As the head descends, the occiput of the fetus rotates toward the symphysis pubis—or, less commonly, toward the hollow of the sacrum—thereby allowing the widest portion of the fetus to negotiate the pelvis at its widest dimension. Owing to the angle of inclination between the maternal lumbar spine and pelvic inlet, the fetal head engages in an asynclitic fashion (i.e., with one parietal eminence lower than the other). With uterine contractions, the leading parietal eminence descends and is first to engage the pelvic floor. As the uterus relaxes, the pelvic floor musculature causes the fetal head to rotate until it is no longer asynclitic.

Extension

Extension occurs once the fetus has descended to the level of the introitus. This descent brings the base of the occiput into contact with the inferior margin at the symphysis pubis. At this point, the birth canal curves upward. The fetal head is delivered by extension and rotates around the symphysis pubis. The forces responsible for this motion are the downward force exerted on the fetus by the uterine contractions along with the upward forces exerted by the muscles of the pelvic floor.

External Rotation

External rotation, also known as restitution, refers to the return of the fetal head to the correct anatomic position in relation to the fetal torso. This can occur to either side depending on the orientation of the fetus; this is again a passive movement that results from a release of the forces exerted on the fetal head by the maternal bony pelvis and its musculature and mediated by the basal tone of the fetal musculature.

Expulsion

Expulsion refers to delivery of the rest of the fetus. After delivery of the head and external rotation, further descent brings the anterior shoulder to the level of the symphysis pubis. The anterior shoulder is delivered in much the same manner as the head, with rotation of the shoulder under the symphysis pubis. After the shoulder, the rest of the body is usually delivered without difficulty.

Normal Progress of Labor

Progress of labor is measured with multiple variables. With the onset of regular contractions, the fetus descends in the pelvis as the cervix both effaces and dilates. With each vaginal examination to judge labor progress, the clinician must assess not only cervical effacement and dilation but fetal station and position. This assessment depends on skilled digital palpation of the maternal cervix and the presenting part. As the cervix dilates in labor, it thins and shortens—or becomes more effaced—over time. Cervical effacement refers to the length of the remaining cervix and can be reported in length or as a percentage. If percentage is used, 0% effacement at term refers to at least a 2 cm long or a very thick cervix, and 100% effacement refers to no length remaining or a very thin cervix. Most clinicians use percentages to follow cervical effacement during labor. Generally, 80% or greater effacement is observed in women who are in active labor. Dilation, perhaps the easiest assessment to master, ranges from closed (no dilation) to complete (10 cm dilated). For most women, a cervical dilation that accommodates a single index finger is equal to 1 cm, and two index fingers' dilation is equal to 3 cm. If no cervix can be palpated around the presenting part, the cervix is 10 cm or completely dilated. The assessment of station, discussed earlier, is important for documentation of progress, but it is also critical when determining if an operative vaginal delivery is feasible. Fetal head position should be regularly determined once the woman is in active labor; ideally, this should occur before significant caput has developed, which obscures the sutures. Like station, knowledge of the fetal position is critical before performing an operative vaginal delivery (see Chapter 14).

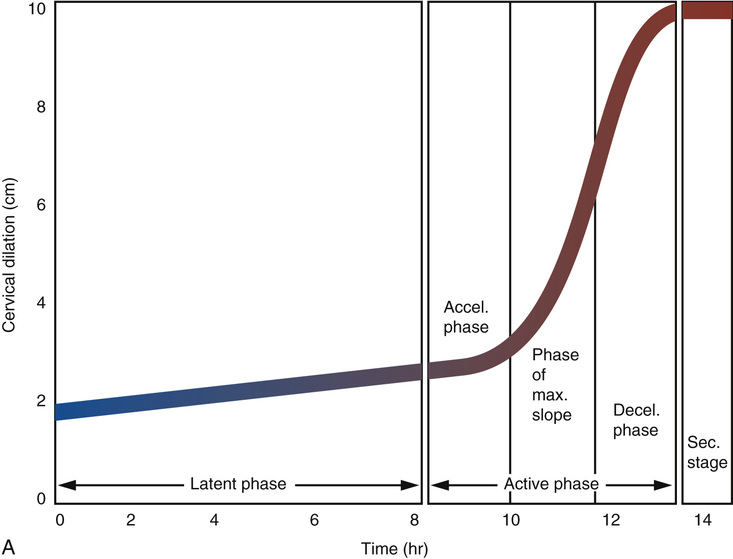

Labor occurs in three stages: the first stage is from labor onset until full dilation of the cervix; the second stage is from full cervical dilation until delivery of the baby; and the third stage begins with delivery of the baby and ends with delivery of the placenta. The first stage of labor is divided into two phases: the first is the latent phase, and the second is the active phase. The latent phase begins with the onset of labor and is characterized by regular, painful uterine contractions and a slow rate of cervical change. When the rate of cervical dilation is accelerated, latent labor ends and active labor begins. Labor onset is a retrospective diagnosis that is difficult to identify objectively. It is defined by the initiation of regular painful contractions of sufficient duration and intensity to result in cervical dilation or effacement. Women are frequently at home during this time; therefore the identification of labor onset depends on patient memory and the timing of contractions in relation to the cervical examination. The active phase of labor is defined as the period in which the greatest rate of cervical dilation occurs. Identification of the point at which labor transitions from the latent to the active phase will depend upon the frequency of cervical examinations and retrospective examination of labor progress. Historically, based upon Friedman's40 seminal data on cervical dilation and labor progress from the 1950s and 1960s, active labor required 80% or more effacement and 4 cm or greater dilation of the cervix. He analyzed labor progress in 500 nulliparous and multiparous women and reported normative data that have been used for more than half a century to define our expectations of normal and abnormal labor.40,41

Friedman revolutionized our understanding of labor because he was able to plot static observations of cervical dilation against time and successfully translate the dynamic process of labor into a sigmoid-shaped curve (Fig. 12-13). Friedman's data popularized the use of the labor graph, which first depicted only cervical dilation and was then later modified to include fetal descent.42 Four-centimeter cervical dilation marks the transition from the latent to the active phase because it corresponds to the flexion point on the averaged labor curve generated from a review of 500 individual labor curves in the original Friedman dataset.40 Rates of 1.5 and 1.2 cm dilation per hour in the active phase for multiparous and nulliparous women, respectively, represent the 5th percentile of normal.41 These data have led to the general concept that in active labor, a rate of dilation of at least 1 cm per hour should occur.

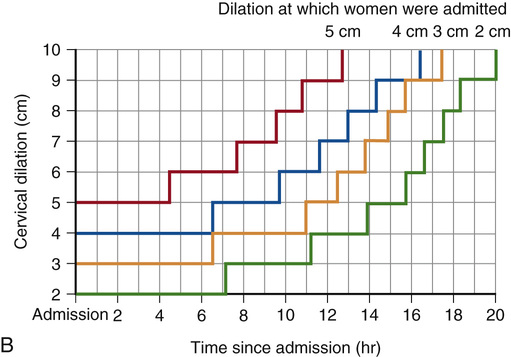

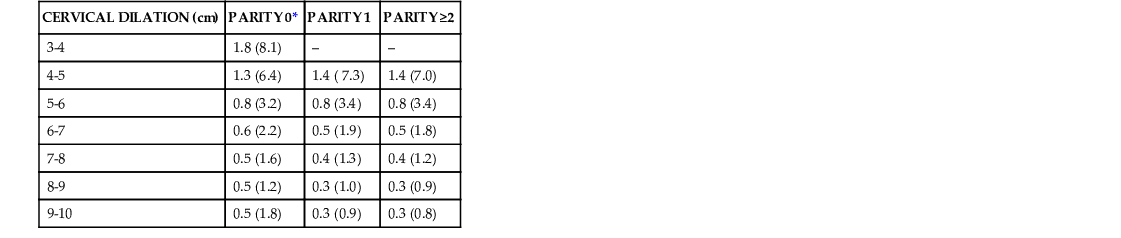

More recent analysis of contemporary labor from several studies challenges our understanding of the cervical dilation at which active labor occurs and suggests that the transition from the latent phase to the active phase of labor is a more gradual process.43 An analysis of labor curves for 1699 multiparous and nulliparous women who presented in spontaneous labor at term and underwent a vaginal delivery determined that only half of the women with a cervical dilation of 4 cm were in the active phase.44 By 5 cm of cervical dilation, 75% of the women were in the active phase, and by 6 cm cervical dilation, 89% of the women were in the active phase.44 Zhang and colleagues45 reviewed data from the National Collaborative Perinatal Project, a historic cohort of 26,838 term parturients in spontaneous labor from 1959 through 1966. This study used a repeated measures analysis to construct labor curves for parturients whose intrapartum management was similar to those studied by Friedman in the 1950s. The cesarean delivery rate was 5.6%, and only 20% of nulliparas and 12% of multiparas received oxytocin for labor augmentation. This study determined that labor progress in nulliparous women who ultimately had a vaginal delivery is in fact slower than previously reported until 6 cm of cervical dilation.45 Specifically, most nulliparous women were not in active labor until approximately 5 to 6 cm of cervical dilation, and the slope of labor progress did not increase until after 6 cm. These findings were confirmed in an analysis46 of contemporary data collected prospectively by the Consortium on Safe Labor, which enrolled and followed 62,415 singleton term parturients who presented in spontaneous labor at 19 institutions from 2002 through 2007. This dataset included a greater percentage of women with oxytocin augmentation (45% to 47%) and epidural analgesia (71% to 84%) compared with those studied by Friedman in the 1950s. Zhang and colleagues45 reported the median and 95th percentile of time to progress from one centimeter to the next and confirmed that labor may take more than 6 hours to progress from 4 to 5 cm and more than 3 hours to progress from 5 to 6 cm regardless of parity (Table 12-2). Multiparas had a faster rate of cervical dilation compared with nulliparas only after 6 cm of cervical dilation had been reached. These data suggest that it would be more appropriate to utilize a threshold of 6 cm cervical dilation to define active phase labor onset and that the rate of cervical dilation for nulliparas at the 95th percentile of normal may be greater than the 1 cm per hour previously expected. These are important findings that suggest clinicians using the Friedman dataset to determine the threshold for active labor may be diagnosing active phase arrest prematurely, which could result in unnecessary cesarean deliveries (see Chapter 13).3,42,45,46

TABLE 12-2

MEDIAN DURATION OF TIME ELAPSED IN HOURS FOR EACH CENTIMETER OF CHANGE IN CERVICAL DILATION IN SPONTANEOUS LABOR STRATIFIED BY PARITY

| CERVICAL DILATION (cm) | PARITY 0* | PARITY 1 | PARITY ≥2 |

| 3-4 | 1.8 (8.1) | – | – |

| 4-5 | 1.3 (6.4) | 1.4 ( 7.3) | 1.4 (7.0) |

| 5-6 | 0.8 (3.2) | 0.8 (3.4) | 0.8 (3.4) |

| 6-7 | 0.6 (2.2) | 0.5 (1.9) | 0.5 (1.8) |

| 7-8 | 0.5 (1.6) | 0.4 (1.3) | 0.4 (1.2) |

| 8-9 | 0.5 (1.2) | 0.3 (1.0) | 0.3 (0.9) |

| 9-10 | 0.5 (1.8) | 0.3 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.8) |

The labor partogram commonly in use today was based upon the graph introduced in 1964 by Schulman and Ledger,47 in which labor progression focused on latent and active phase only. Another and perhaps better approach, based upon contemporary data from the Consortium on Safe Labor,46 is shown in Figure 12-13, along with the modified Friedman curve. The Zhang partogram (see Fig. 12-13, B) graphically depicts the 95th percentile of the duration of labor in hours stratified by cervical dilation on admission. Cervical dilation is not recorded as a continuous measure, and as a result, interval cervical change over time is depicted in a stair-step pattern. The Zhang partogram may be more appropriate for the identification of those parturients with a duration of labor that exceeds the 95th percentile of normal. Its clinical utility, however, has yet to be confirmed and validated.

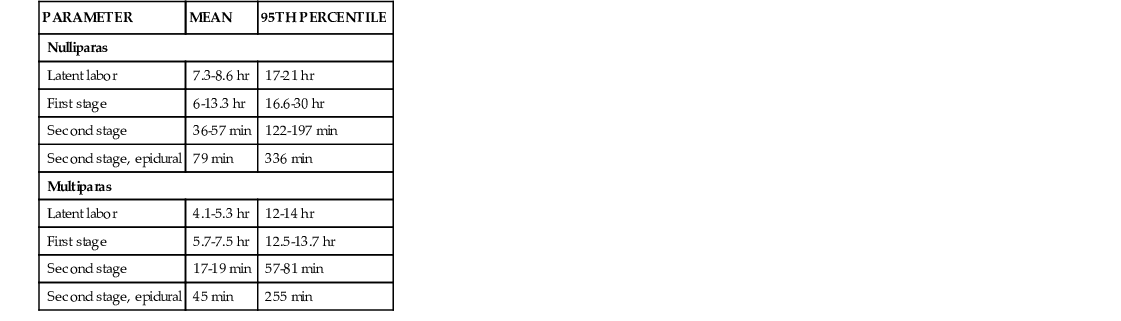

Factors that affect the duration of labor include parity, maternal body mass index (BMI), fetal position, maternal age, and fetal size. Longer labors are associated with increased maternal BMI,48 fetal position other than OA,49 and older maternal age.5,50,51 Data conflict in regard to the effect of epidural use on the duration of the first stage of labor. Retrospective cohort studies have suggested that epidural use may significantly increase the duration of the first stage of labor.47,52,53 However, a Cochrane meta-analysis of 11 RCTs did not identify a statistically significant difference in the mean length of the first stage of labor in women randomized to epidural analgesia compared with those who went without (average mean difference [MD] 18.51 min; 95% CI, −12.91 to 49.92).32 Additional studies are needed to confirm the effect of epidural use on the 95th percentile duration for the first stage of normal labor. Table 12-3 summarizes the means and 95th percentile duration of first- and second-stage labor that have been reported.40,41,46,47,52-55

TABLE 12-3

SUMMARY OF MEANS AND 95TH PERCENTILES FOR DURATION OF FIRST- AND SECOND-STAGE LABOR

| PARAMETER | MEAN | 95TH PERCENTILE |

| Nulliparas | ||

| Latent labor | 7.3-8.6 hr | 17-21 hr |

| First stage | 6-13.3 hr | 16.6-30 hr |

| Second stage | 36-57 min | 122-197 min |

| Second stage, epidural | 79 min | 336 min |

| Multiparas | ||

| Latent labor | 4.1-5.3 hr | 12-14 hr |

| First stage | 5.7-7.5 hr | 12.5-13.7 hr |

| Second stage | 17-19 min | 57-81 min |

| Second stage, epidural | 45 min | 255 min |

Factors significantly associated with a prolonged second stage included induced labor, chorioamnionitis, older maternal age, OP position, delayed pushing, nonblack ethnicity, epidural analgesia, and parity of five or more.50,56 Of note, Friedman's second-stage lengths are somewhat artificial because most nulliparous women in that era had a forceps delivery once the duration of the second stage reached 2 hours. More recent labor duration data that evaluated women in spontaneous labor without augmentation or operative delivery from multiple countries report similar mean labor durations, which suggests that these normative data are reliable and useful (see Table 12-3). A Cochrane meta-analysis32 of 13 RCTs confirmed that epidural use significantly increased the mean duration of the second stage compared with no epidural (average MD in second stage length with an epidural, 13.66 min; 95% CI, 6.67 to 20.66 min). According to the ACOG/Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM) obstetric care consensus,57 it is important to consider not just the mean or median duration of the second stage with epidural analgesia but also the 95th percentile duration. In a recent large retrospective cohort study of 33,239 women with term spontaneous vaginal deliveries, an epidural was associated with an increase in the 95th percentile duration of the second stage in nulliparous women by 94 minutes (P < .001).54 For multiparous women with a spontaneous vaginal delivery, an epidural increased the 95th percentile duration of the second stage by 102 minutes (P < .001; see Chapter 16).54 Determination of the upper limits of time for normal second-stage labor that incorporates epidural use and other more contemporary labor interventions are helpful in identifying normative values for labor duration that are associated with the lowest risk of maternal and neonatal morbidity.52,53,58

The third stage of labor is generally short. In a case series of nearly 13,000 singleton vaginal deliveries at greater than 20 weeks' gestation, the median third-stage duration was 6 minutes and exceeded 30 minutes in only 3% of women.59 However, third stages lasting greater than 30 minutes were associated with significant maternal morbidity that included an increased risk of blood loss greater than 500 mL, a decrease in postpartum hematocrit by greater than or equal to 10%, need for dilation and curettage, and a sixfold increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage.59,60 These data suggest that if spontaneous separation does not occur, manual removal and/or extraction of the placenta should be considered after 30 minutes to reduce the risk of maternal hemorrhage. The factors associated with a prolonged third stage of labor include preterm delivery, preeclampsia, labor augmentation, nulliparity, maternal age over 35 years, and a second-stage labor duration greater than 2 hours.61,62 Several strategies to minimize the risk of postpartum hemorrhage for women in the third stage of labor have been recommended and include early administration of a uterotonic agent after delivery of the anterior fetal shoulder, early cord clamping, controlled traction on the umbilical cord, and fundal massage to facilitate early placental separation.63,64 A Cochrane meta-analysis63 of seven randomized to quasi-randomized controlled studies found that for a heterogeneous population of women at mixed risk of bleeding, active management of the third stage of labor was associated with a significant reduction in blood loss over 1000 mL (relative risk [RR], 0.34; 95% CI, 0.14 to 0.87) and a lower risk of anemia (hemoglobin [Hgb], <9 g/dL; average RR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.30 to 0.83). However, a significant reduction in neonatal birthweight was reported, likely due to early cord clamping and reduced time for placental transfusion. In women at low risk for postpartum hemorrhage, active management of labor was not associated with a significant reduction in the risk of maternal hemorrhage (blood loss >500 mL) or maternal anemia (Hgb <9 g/dL) compared with women who were expectantly managed.63

Interventions That Affect Normal Labor Outcomes

Various interventions have been suggested to promote normal labor progress, including maternal ambulation and upright maternal positioning during active labor.65,66 A well-designed randomized trial65 of over 1000 low-risk women in early labor at 3- to 5-cm cervical dilation compared ambulation with usual care and found no differences in the duration of the first stage, need for oxytocin, use of analgesia, neonatal outcomes, or route of delivery. These results suggest that given appropriate staffing resources and fetal surveillance protocols, walking in the first stage of labor is an option that may be considered for low-risk women. A Cochrane review of 25 randomized to quasi RCTs of considerable heterogeneity found that in low-risk nulliparous women, upright rather than recumbent positioning during labor was associated with a significantly shorter first stage of labor by 1 hour and 22 minutes (average MD, −1.36; 95% CI, −2.22 to −0.51), less epidural use, and a reduction in the risk of cesarean delivery by 30% (RR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.54 to 0.94).66 Women should be encouraged to consider upright positioning in labor, and the potential benefits should be discussed to facilitate informed decision making. In a Cochrane review67 of 22 trials that involved 15,288 low-risk women randomized to continuous labor support (doula) compared with routine care, the presence of a labor doula was associated with a significant reduction in the use of analgesia, oxytocin, and operative vaginal delivery (RR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.85 to 0.96) or cesarean delivery (RR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.67 to 0.91) and an increase in personal satisfaction. These data were compelling enough for doula support to receive an A rating, meaning that it should be recommended for use during labor.68 Other models of continuous labor support with a friend or family member should be encouraged if a doula is unavailable.

The benefits of IV hydration in labor have been less well studied. The use of IV fluids is a routine practice in many labor and delivery units, although its benefit compared with oral hydration has not been well elucidated, and the volume and type of IV fluid that may promote optimal progress in labor is unclear. A Cochrane review69 of nine randomized trials included studies of considerable heterogeneity. Two trials compared women randomized to receive up to 250 mL/hr of Ringer's lactate solution and oral intake versus oral intake alone. No difference was found in the cesarean delivery rate. However, a reduced duration of labor was reported for women with a vaginal delivery who received Ringer's lactate (MD, −28.86 min; 95% CI, −47.41 to −10.30). Four trials compared rates of IV fluids (125 mL/hr vs. 250 mL/hr) in women whose oral intake was restricted, and a significant reduction in the duration of labor was reported in women who received IV fluid at 250 mL/hr.69 With regard to the type of IV fluid, in a randomized trial of nulliparas in active labor, IV administration at 125 mL/min of dextrose in normal saline (NS) was associated with a significant reduction in labor length and in second-stage length compared with normal saline.70 Although the available data suggest that IV fluid is beneficial in labor, additional studies are needed to determine the risks and benefits of appropriate oral hydration. Furthermore, the optimal volume of fluid replacement in labor from all sources, oral and IV, is unclear.

Active Management of Labor

Dystocia refers to a lack of progress of labor for any reason, and it is the most common indication for cesarean delivery (CD) in nulliparous women and the second most common indication for CD in multiparous women. In the late 1980s, in an effort to reduce the rapidly rising rate of CD, active management of labor was popularized in the United States based on findings in Ireland, where the routine use of active management was associated with very low rates of CD.71 Protocols for active management included (1) admission only when labor was established, evidenced by painful contractions and spontaneous rupture of membranes, 100% effacement, or passage of blood-stained mucus; (2) artificial rupture of membranes on diagnosis of labor; (3) aggressive oxytocin augmentation for labor progress of less than 1 cm/hr with high-dose oxytocin (6 mIU/min initial dose, increased by 6 mIU/min every 15 min to a maximum of 40 mIU/min); and (4) patient education.71 Observational data suggested that this management protocol was associated with rates of CD of 5.5% and delivery within 12 hours in 98% of women.71 Only 41% of the nulliparas actually required oxytocin augmentation. Multiple nonrandomized studies were subsequently published that attempted to duplicate these results in the United States and Canada.72-75 Two of these reported a significant reduction in cesarean delivery when compared with historical controls.72,74 However, in two of three RCTs, no significant decrease in the rate of cesarean delivery was observed with active compared with routine management of labor.76-77 In the third RCT, the overall CD rate was not significantly different. However, when confounding variables were controlled, CD was significantly lower in the actively managed group.75 In all randomized trials, labor duration was significantly decreased by a range of 1.7 to 2.7 hours, and neonatal morbidity was not different between groups. In a recent Cochrane review,78 a meta-analysis of 11 trials (7753 women) concluded that early oxytocin augmentation in women with spontaneous labor was associated with a significant decrease in CD (RR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.77 to 0.99). A meta-analysis of eight trials (4816 women) determined that early amniotomy and oxytocin augmentation was associated with a significantly shortened duration of labor (average MD, 1.28 hr; 95% CI, −1.97 to −0.59).78 Of note, amniotomy alone did not affect labor length or the rate of CD. This reduction in labor duration has significant cost and bed-management implications, especially for busy labor and delivery units. Perhaps the most important factor in active management is delaying admission until active labor has been established.

Second Stage of Labor

Abnormal progress in fetal descent is the dystocia of the second stage. A wide range of mean and 95th percentile second-stage labor durations have been reported for vaginal deliveries and are influenced by parity, presence or absence of epidural analgesia, and local or regional practice patterns (see Table 12-3). According to the summary of a National Institutes of Health (NIH)–sponsored workshop on prevention of the first cesarean, no specific threshold maximum second-stage duration exists beyond which all women should undergo operative vaginal delivery.79 However, a direct correlation has been found between second-stage duration, adverse maternal outcomes (hemorrhage, infection, perineal lacerations), and the likelihood of a successful vaginal delivery.80 A secondary analysis42 of a multicenter study on fetal pulse oximetry compared second-stage duration with maternal and perinatal outcomes in 4126 nulliparous women. Chorioamnionitis (overall rate, 3.9%), third- and fourth-degree lacerations (overall rate, 8.7%), and uterine atony (overall rate, 3.9%; combined OR, 1.31 to 1.60; 95% CI, 1.14 to 1.86) were significantly increased with longer second-stage duration. Adverse maternal outcomes with longer labor duration in multiparous women have also been reported.81,82 In regard to the correlation between adverse neonatal outcomes and longer second-stage lengths, the reports are mixed; one study reported a lack of association between neonatal outcomes and the duration of the second stage of labor in nulliparous women.80,83-85 However, in a study of 43,810 nulliparas in the second stage of labor, second-stage lengths of greater than 3 hours were associated with increased maternal and neonatal morbidity.86 In nulliparous women with an epidural who had a nonoperative vaginal delivery, a prolonged second stage greater than 3 hours was associated with an increased risk of a shoulder dystocia (adjusted OR, 1.62; 95% CI, 1.17 to 1.65), 5-minute Apgar score less than 4 (adjusted OR, 2.58; 95% CI, 1.07 to 6.17), increased risk of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission (adjusted OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.53), and neonatal sepsis (adjusted OR, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.39 to 2.91).86 It should be noted that although these results are significant, the absolute incidence of each event is extremely low. These findings suggest that the benefits of vaginal delivery with second-stage prolongation must be weighed against possible small but significant increases in neonatal risk.80 Although less frequent, adverse neonatal outcomes for multiparous women with a prolonged second-stage duration have also been reported.80-82

Based upon the available evidence, a workshop convened by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Health Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), ACOG, and SMFM recommend at least a 3- to 4-hour second-stage duration for nulliparous women and at least a 2- to 3-hour second-stage duration for multiparas, if maternal and fetal conditions permit.79 Documentation of patient progress and individualization of care is paramount because longer durations of pushing may also be appropriate. Epidural use or fetal malposition, for example, may prolong the duration of the second stage. Recommended guidelines to identify those with abnormal prolongation of the second stage stratified by parity and epidural use are detailed in Table 12-4. These limits should not be used arbitrarily to justify ending the second stage. They can, however, be used to identify a subset of women who require further evaluation.83

TABLE 12-4

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR 95TH PERCENTILE DURATION FOR THE SECOND STAGE OF LABOR

| 95TH PERCENTILE | |

| Multiparas | |

| Second stage without an epidural | 2 hours |

| Second stage with an epidural | 3 hours |

| Nulliparas | |

| Second stage without an epidural | 3 hours |

| Second stage with an epidural | 4 hours |

As with active labor, poor progress in the second stage may be related to inadequate contractions; therefore initiating oxytocin in the second stage may be effective to facilitate descent if contraction frequency is diminished. If malposition is diagnosed, rotation to OA—either manually or by forceps—may also be indicated in the second stage to facilitate descent. For women with a prolonged second-stage duration, arbitrary time cutoffs are unnecessary if steady progress is observed and fetal status is reassuring.87-91 Whereas evidence suggests maternal morbidity is significantly higher in women with a prolonged second stage,83,92 it is important to note that the decision to proceed with an operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery simply to shorten the second stage must be based upon weighing the risks of operative delivery against the risks associated with a prolonged second stage and the likelihood of a successful vaginal delivery (see Chapters 13 and 14).

Multiple factors influence the duration of the second stage; these include epidural analgesia, nulliparity, older maternal age, maternal BMI, longer active phase, greater birthweight, and excess maternal weight gain.83,92 Modifiable factors that have been evaluated in management of the second stage include maternal position, decreasing or discontinuation of epidural analgesia (see Chapter 16), and delayed pushing. A Cochrane review of five RCTs that studied the risks and benefits of discontinuation of second-stage epidural analgesia found no difference in route of delivery, operative vaginal delivery rate, or second-stage duration.93-96 However, a Cochrane review of 38 RCTs to evaluate epidural versus no epidural in labor found that epidural analgesia was clearly associated with an increased duration of the second stage of labor (MD, 13.66 min; 95% CI, 6.67 to 20.66) and rate of operative delivery (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.28 to 1.57).32,95,97 A recent retrospective review98 of second-stage durations for 4605 women reported a 60-minute increase in the median duration of second-stage labor for nulliparas with an epidural compared with those without. In women who had a vaginal delivery, the 95th percentile duration of the second stage was 95 minutes longer for nulliparas with an epidural and 101 minutes longer for multiparas with an epidural compared with those who went without an epidural (P < .001). Delayed pushing was compared with immediate pushing in the second stage in nulliparas with epidural analgesia to determine whether this strategy would reduce the need for operative delivery.97,99-101 It has been suggested that delaying pushing until the woman feels the urge to push would maximize maternal pushing efforts, reduce maternal exhaustion, and decrease the risk of operative vaginal delivery.

A meta-analysis of 12 RCTs found that delayed pushing was associated with an increased rate of vaginal delivery. However, this benefit was not statistically significant among the quality studies reviewed.97,99-102 Delayed pushing prolonged the duration of the second stage (weighted MD, 56.92 min; 95% CI, 42.19 to 71.64) and shortened the duration of active pushing (weighted MD, 21.98 min; 95% CI, −31.29 to −12.68).102 However, no significant difference was found in the operative vaginal delivery rate.102 Only one trial reported a significant decrease in midpelvic operative deliveries.99 Risks associated with delayed pushing have also been reported. In a retrospective evaluation of 5290 term multiparous and nulliparous women, delayed pushing was associated with a statistically significant increase in cesarean and operative delivery rates, increased maternal fever, and a significant decrease in arterial cord pH.103,104 Data suggest that delayed pushing is not associated with fewer cesarean or operative deliveries and may have maternal risks. Additional studies are needed to determine whether delayed pushing is associated with increased neonatal risk.

Finally, the effect of maternal position in the second stage has been evaluated.105,106 A Cochrane review107 of five RCTs evaluated the effect of any upright position compared with recumbent positioning in the second stage of labor on route of delivery and duration of labor. No statistically significant difference between groups was observed for operative delivery, duration of second stage, or neonatal outcome.107 A significant increase in the percent of women with an intact perineum in the upright group was identified106; therefore nonrecumbent positioning in the second stage should be considered.

Spontaneous Vaginal Delivery

Preparation for delivery should take into account the patient's parity, the progression of labor, fetal presentation, and any labor complications. Among women for whom delivery complications are anticipated (risk factors for shoulder dystocia or multiple gestation), transfer to a larger and better equipped delivery room, removal of the foot of the bed, and delivery in the lithotomy position may be appropriate. If no complications are anticipated, delivery can be accomplished with the mother in her preferred position. Common positions include the lateral (Sims) position or the partial sitting position.

The goals of clinical assistance at spontaneous delivery are the reduction of maternal trauma, prevention of fetal injury, and initial support of the newborn. When the fetal head crowns and delivery is imminent, gentle pressure should be used to maintain flexion of the fetal head and to control delivery, potentially protecting against perineal injury. Once the fetal head is delivered, external rotation (restitution) is allowed. If a shoulder dystocia is anticipated, it is appropriate to proceed directly with gentle downward traction of the fetal head before restitution occurs. During restitution, nuchal umbilical cord loops should be identified and reduced; in rare cases in which simple reduction is not possible, the cord can be doubly clamped and transected. The anterior shoulder should then be delivered by gentle downward traction in concert with maternal expulsive efforts; the posterior shoulder is delivered by upward traction. These movements should be performed with the minimal force possible to avoid perineal injury and traction injuries to the brachial plexus.

No evidence shows that DeLee suction reduces the risk of meconium aspiration syndrome in the presence of meconium; thus this should not be performed.108 For a vigorous infant, the ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) no longer recommend routine suctioning in the presence of meconium. If the infant is depressed, and meconium staining is evident, intubation and visualization of meconium or other foreign material below the vocal cords is recommended and should be performed by appropriately trained providers per AAP guidelines.109

The timing of cord clamping is usually dictated by convenience and is commonly performed immediately after delivery. However, an ongoing debate exists about the benefits and risks to the newborn of late cord clamping. A Cochrane review of 15 RCTs that compared late (>2 minutes) and immediate cord clamping in term infants showed a significant increase in infant hematocrit, ferritin, and stored iron at 2 to 6 months with no significant increase in the risk of maternal hemorrhage.110,111 However, a significant increase was also seen in neonatal polycythemia and treatment for neonatal jaundice in the delayed group. A Cochrane review112 of 15 RCTs to compare late (>30 seconds) to immediate cord clamping in preterm infants (<37 weeks' gestation) showed significant decreases in anemia that required transfusion, intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), and necrotizing enterocolitis in infants with delayed clamping. Those infants who had their cords clamped later were also noted to have a higher bilirubin levels. No significant difference was reported in the risk of grade 3 or 4 IVH or interventricular leukomalacia, primarily due to considerable heterogeneity among the studies.112 In 2012, ACOG issued a committee opinion affirming the practice of delayed cord clamping for preterm infants in light of the up to 50% reduction in the risk of IVH reported for these infants when delayed cord clamping is performed.113 However, for term infants, ACOG determined that evidence was insufficient to either confirm or refute the benefits of delayed cord clamping. Additional studies are needed to determine barriers to implementation of delayed cord clamping in preterm infants and to further determine the benefits and risks of this practice for term infants in resource-rich locations.114

If possible, the steps described here are best done with the infant on the mother's abdomen. Initially, the infant should be wiped dry and kept warm while any mucus remaining in the airway is suctioned. Keeping the infant warm is particularly important, and because heat is lost quickly from the head, placing a hat on the infant is appropriate. After clamping of the cord, the vigorous term infant should be placed on the mother's bare skin if at all possible. Early skin-to-skin contact (SSC) refers to the placement of the naked infant in a prone position onto the mother's bare chest and abdomen near the breast with the infant's side and back covered by blankets or towels.115 Early SSC is recommended for the healthy term newborn immediately after vaginal delivery and as soon as possible after cesarean delivery by ACOG, the AAP, and the Baby-Friendly Health Initiative developed by the World Health Organization.116,117 Meta-analysis of data from RCTs (13 trials, 702 participants) suggests that immediate or early SSC increases the likelihood of breastfeeding initiation at 1 to 4 months (RR 1.27; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.53) and results in higher blood glucose at 75 to 90 min of life compared with standard care (MD, 10.56 mg/dL; 95% CI, 8.40 to 12.72).118 Positive effects of SSC on maternal-infant bonding, breastfeeding duration, cardiorespiratory stability, and body temperature have also been demonstrated.118-120 The term Kangaroo care refers to a model of postdelivery care that includes continuous SSC contact and exclusive breastfeeding for low birthweight (LBW) infants, and it was originally promoted as an alternative to incubators in resource-poor settings. A meta-analysis of the RCTs identified a significant reduction in neonatal mortality, nosocomial infection and sepsis, and hypothermia as well as improvements in measures of infant growth, breastfeeding, and mother-infant attachment with kangaroo care compared with conventional methods for LBW infants.121 Additional prospective RCTs are needed to further characterize the benefits and limitations, if any, of SSC and kangaroo care in term and stable LBW infants; in resource-rich, compared with resource-poor, settings; and after cesarean delivery.

Delivery of the Placenta and Fetal Membranes

The third stage of labor can be managed either passively or actively. Passive management is characterized by clamping of the cord once spontaneous pulsations have ceased and delivery of the placenta by gravity or spontaneously, without manipulation of the uterus or traction on the cord. Placental separation is heralded by lengthening of the umbilical cord and a gush of blood from the vagina, signifying separation of the placenta from the uterine wall. With passive management, uterotonic medications are not given until after delivery of the placenta. With active management of the third stage, uterotonic medication is administered shortly after delivery of the baby but prior to delivery of the placenta. Controlled umbilical cord traction and countertraction are used to support the uterus until the placenta separates and is delivered, followed by uterine massage after delivery of the placenta. Two techniques of controlled cord traction are commonly used to facilitate separation and delivery of the placenta: in the Brandt-Andrews maneuver, a hand pressed against the abdomen secures the uterine fundus to prevent uterine inversion, while the other hand exerts sustained downward traction on the umbilical cord; with the Créde maneuver, the cord is fixed with the lower hand, and while the uterine fundus is secured and sustained, upward traction is applied by a hand pressed against the abdomen. Care should be taken to avoid evulsion of the cord.

Implementation of active management strategies in the third stage of labor can significantly decrease the risk of postpartum hemorrhage. In a meta-analysis of three RCTs to compare active to expectant management, subjects randomized to active management were 66% less likely to have postpartum hemorrhage (estimated blood loss [EBL] ≥1000 mL; RR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.14 to 0.87).122,123 Active management of the third stage of labor is recommended by ACOG District II and the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative (CMQCC) as an integral component of multifaceted perinatal quality initiatives to reduce the severe maternal morbidity and mortality that results from obstetric hemorrhage. Active management of the third stage of labor specifically includes administration of dilute IV oxytocin or 10 units of intramuscular oxytocin after delivery of the fetus and prior to delivery of the placenta (ACOG District II). In the CMQCC obstetric hemorrhage protocol, additional components of the active management strategy include umbilical cord clamping at or prior to 2 minutes after delivery, controlled cord traction to facilitate delivery of the placenta, followed by fundal massage to facilitate uterine involution (CMQCC).

After delivery, the placenta, umbilical cord, and fetal membranes should be examined. Placental weight (excluding membranes and cord) varies with fetal weight, with a ratio of approximately 1 : 6. Abnormally large placentae are associated with such conditions as hydrops fetalis and congenital syphilis. Inspection and palpation of the placenta should include the fetal and maternal surfaces and may reveal areas of fibrosis, infarction, or calcification. Although each of these conditions may be seen in the normal term placenta, extensive lesions should prompt histologic examination. Adherent clots on the maternal placental surface may indicate recent placental abruption; however, their absence does not exclude the diagnosis. A missing placental cotyledon or a membrane defect suggestive of a missing succenturiate lobe also suggests retention of a portion of placenta and should prompt further clinical evaluation. Routine manual exploration of the uterus after delivery is unnecessary unless retained products of conception or a postpartum hemorrhage is suspected.

The site of insertion of the umbilical cord into the placenta should be noted. Abnormal insertions include marginal insertion, in which the cord inserts into the edge of the placenta, and membranous insertion, in which the vessels of the umbilical cord course through the membranes before attachment to the placental disc. The cord should be inspected for length; the correct number of umbilical vessels, normally two arteries and one vein; true knots; hematomas; and strictures. The average cord length is about 50 to 60 cm. A single umbilical artery discovered on pathologic examination is associated with an increased risk of fetal growth restriction and up to a 6.77-fold higher risk of one or more major congenital anomalies (OR, 6.77; 95% CI, 5.7 to 8.06).124-127 Therefore this finding should be relayed to the attending neonatologist or pediatrician, and any abnormalities of the placenta or cord should be noted in the mother's chart.

Episiotomy and Perineal Injury and Repair

Following delivery of the placenta, the vagina and perineum should be carefully examined for evidence of injury. If a laceration is seen, its length and position should be noted and repair should be initiated. Adequate analgesia, either regional or local, is essential for repair. Special attention should be paid to repair of the perineal body, the external anal sphincter, and the rectal mucosa (see Chapter 18). Failure to recognize and repair rectal injury can lead to serious long-term morbidity, most notably fecal incontinence. The cervix should be inspected for lacerations if an operative delivery was performed or when bleeding is significant with or after delivery.

Perineal injuries, either spontaneous or with the episiotomy, are the most common complications of spontaneous or operative vaginal deliveries. A first-degree tear is defined as a superficial tear confined to the epithelial layer; it may or may not need to be repaired depending on size, location, and amount of bleeding. A second-degree tear extends into the perineal body but not into the external anal sphincter. A third-degree tear involves superficial or deep injury to the external anal sphincter, whereas a fourth-degree tear extends completely through the sphincter and the rectal mucosa. All second-, third-, and fourth-degree tears should be repaired (see Chapter 18). Significant morbidity is associated with third- and fourth-degree tears, including risk of flatus and stool incontinence, rectovaginal fistula, infection, and pain (see Chapter 14). Primary approximation of perineal lacerations affords the best opportunity for functional repair, especially if rectal sphincter injury is evident. The external anal sphincter should be repaired by direct apposition or overlapping the cut ends and securing them using interrupted sutures.

Episiotomy is an incision into the perineal body made during the second stage of labor to facilitate delivery. It is by definition at least a second-degree tear. Episiotomy can be classified into two broad categories, midline and mediolateral. With a midline episiotomy, a vertical midline incision is made from the posterior fourchette toward the rectum (Fig. 12-14). After adequate analgesia has been achieved, either local or regional, straight Mayo scissors are generally used to perform the episiotomy. Care should be taken to displace the perineum from the fetal head. The size of the incision depends on the length of the perineum but is generally approximately half of the length of the perineum and should be extended vertically up the vaginal mucosa for a distance of 2 to 3 cm. Every effort should be made to avoid direct injury to the anal sphincter. Complications of midline episiotomy include increased blood loss, especially if the incision is made too early; fetal injury; and localized pain. With a mediolateral episiotomy, an incision is made at a 45-degree angle from the inferior portion of the hymeneal ring (Fig. 12-15). The length of the incision is less critical than with midline episiotomy, but longer incisions require lengthier repair. The side to which the episiotomy is performed is usually dictated by the dominant hand of the practitioner. Because such incisions appear to be moderately protective against severe perineal trauma, if an episiotomy is needed, the mediolateral episiotomy is the procedure of choice for women with inflammatory bowel disease (see Chapter 48) because of the critical need to prevent rectal injury. Historically, it was believed that episiotomy improved outcome by reducing pressure on the fetal head, protecting the maternal perineum from extensive tearing and preventing subsequent pelvic relaxation. However, consistent data since the late 1980s confirm that midline episiotomy does not protect the perineum from further tearing, and data do not show that episiotomy improves neonatal outcome.128,129 Midline episiotomy was associated with a significant increase in third- and fourth-degree lacerations in spontaneous vaginal delivery in nulliparous women with both spontaneous and operative vaginal delivery.128-135 Episiotomy had the highest odds ratio (OR, 3.2; CI, 2.73 to 3.80) for anal sphincter laceration in a large study of nulliparous women when compared with other risk factors, including forceps delivery.136 Few papers reported that midline episiotomy was associated with no difference in fourth-degree tears compared with no episiotomy.137 Randomized trials that compared routine to indicated use of episiotomy report a 23% reduction in perineal lacerations that required repair in the indicated group (11% to 35%).138 Finally, a recent Cochrane review of eight RCTs that compared restrictive to routine use of episiotomy showed a significant reduction of severe perineal tears, suturing, and healing complications in the restrictive group.139 Although the restrictive episiotomy group had a significantly higher incidence of anterior tears, no difference was found in pain measures between the groups. All of these findings were similar whether midline or mediolateral episiotomy was used. Based on the lack of consistent evidence that episiotomy is of benefit, routine episiotomy has no role in modern obstetrics.128,129,139-141 In fact, a recent evidence-based review recommended that episiotomy should be avoided if possible, based on U.S. Preventive Task Force quality of evidence.68 Based on these data and the ACOG recommendations,141 rates of midline episiotomy have decreased, although episiotomies are performed in 10% to 17% of deliveries, which suggests that elective episiotomy continues to be performed.131-138 In one study, decreasing episiotomy rates from 87% in 1976 to 10% in 1994 were associated with a parallel decrease in the rates of third- or fourth-degree lacerations (9% to 4%) and an increase in the incidence of an intact perineum (10% to 26%).131

The relationship of episiotomy to subsequent pelvic relaxation and incontinence has been evaluated, and no studies suggest that episiotomy reduces risk of incontinence. Fourth-degree tears are clearly associated with future incontinence,142 and neither midline nor mediolateral episiotomy is associated with a reduction in incontinence.143 No data suggest that episiotomy protects the woman from later incontinence; therefore avoidance of fourth-degree tearing should be a priority.

If an episiotomy is deemed indicated, the decision of which type to perform rests on their individual risks. It does appear that mediolateral episiotomy is associated with fewer fourth-degree tears compared with midline episiotomy.144-146 However, other studies do not show benefit of mediolateral over midline episiotomy for future prolapse.143 Chronic complications such as unsatisfactory cosmetic results and inclusions within the scar may be more common with mediolateral episiotomies, and blood loss is greater. Finally, it must be remembered that neither episiotomy type has been shown to reduce severe perineal tears compared with no episiotomy.

Although there is no role for routine episiotomy, indicated episiotomy should be performed in select situations, and providers should receive training in the skill.137 Potential indications for episiotomy include the need to expedite delivery in the setting of FHR abnormalities or for relief of shoulder dystocia.

Ultrasound in Labor and Delivery

Ultrasound is a useful adjunct to the clinical examination in the peripartum period. Sonographic findings may be used to confirm the clinical impression of fetal lie and presentation and gestational age when needed. In women with vaginal bleeding, ultrasound can identify placental location and rule out placenta previa prior to a digital examination of the cervix. In women with twins, ultrasound estimation of fetal lie and weight are an integral component of patient counseling regarding mode of delivery for the first and second twin. In women with a breech-presenting fetus at term, ultrasound can be used to confirm presentation, placental location, and amniotic fluid volume prior to patient counseling and performance of a breech version. In the third stage of labor, ultrasound may be used to assist with removal of the placenta for those with a prolonged third stage and/or to better facilitate uterine evacuation during a postpartum hemorrhage.

The association between sonographic cervical length (CL) at term and labor outcome has also been studied. An evaluation of weekly CL measurements between 37 and 40 weeks in term nulliparous women found that cervical shortening could only be documented in 50% of the participants prior to onset of spontaneous labor and that 25% of the participants had a CL of more than 30 mm within the last 48 hours prior to delivery.147 CL measurements obtained between 37 and 38 weeks' gestation were found to have a low sensitivity and negative predictive value for spontaneous labor prior to 41 weeks' gestation. In an evaluation of a more ethnically heterogeneous population, however, a significant correlation was identified between a single CL measurement obtained between 37 and 40 weeks, delivery within 7 days, and delivery prior to 41 weeks' gestation.148 A term cervical length of 25 mm had a sensitivity of 77.5% and a negative predictive value 84.7% for spontaneous labor within 7 days. A CL of 30 mm had a sensitivity of 73.1%, specificity of 40.7%, and a positive predictive value of 81% for delivery prior to 41 weeks' gestation in the cohort studied.148 Although these data are interesting and encouraging, additional studies are needed to determine whether term CL evaluation can be used as an adjunct to the clinical examination to better distinguish those who are most likely to have spontaneous labor between 37 and 40 weeks' gestation from those who would benefit from reassurance and continued expectant management.