▪ A healthy lymphatic system is generally able to prevent or decrease the amount of acute edema. Under normal conditions, the transport capacity of the lymphatic system is approximately 10 times greater than the physiologic amount of the lymphatic loads.

▪ The decisive difference between lymphedema and virtually all other types of edema is the high content of plasma proteins in the interstitial fluid.

▪ The diagnosis of lymphedema is made in most cases by patient history, systems review, inspection, palpation, and a few select noninvasive tests such as volume or girth measurement.

▪ Tissue lesions common in lymphedema, caused by the impaired lymph vascular system and/or other co-morbid conditions, may present as simple superficial excoriations to multifarious ulcers with complex etiologies.

▪ Compression is the cornerstone of lymphedema therapy.

▪ Complete decongestive therapy is a two-phase intervention for lymphedema that is noninvasive, highly effective, and cost-effective that can reduce and maintain limb size.

▪ The goal of exercise is to improve lymphatic flow without adding undue stress to the impaired lymphatic system.

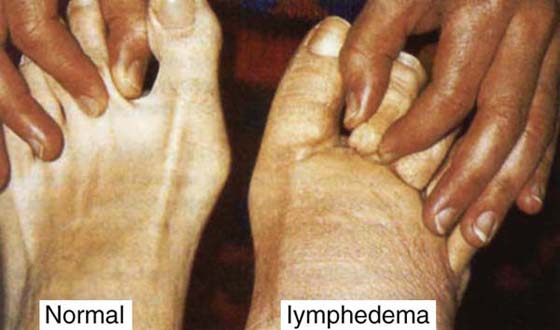

Lymphedema is a chronic, incurable condition that is characterized by an abnormal collection of fluid owing to an anatomic alteration of the lymphatic system.1 Throughout the world, it is estimated that one person in 30 is afflicted with lymphedema.2 Lymphedema can lead to significant impairments in function, integumentary disorders, pain, and psychological issues. Appropriate identification and intervention of this disease can improve functional and aesthetic outcomes and patient quality of life. This chapter describes the function of the lymphatic system and the etiologies of lymphedema. Examination, intervention, and preventive measures are discussed, as well as impairments associated with lymphedema and other complications involving the upper extremity.

The lymphatic system has two main functions. First, it provides significant immune function by protecting the body from disease and infection via production, maintenance, and distribution of lymphocytes. The second function is the facilitation of fluid transport from the interstitial tissues back into the bloodstream. This fluid transport maintains normal blood volume and eliminates chemical imbalances in the interstitial fluid.3 The substances transported by the lymphatic system are called lymphatic loads (LL) and consist of protein, water, cellular debris, and fat (from the digestive system). These lymphatic loads are filtered by regional and central lymph nodes before reentry into the venous blood system.

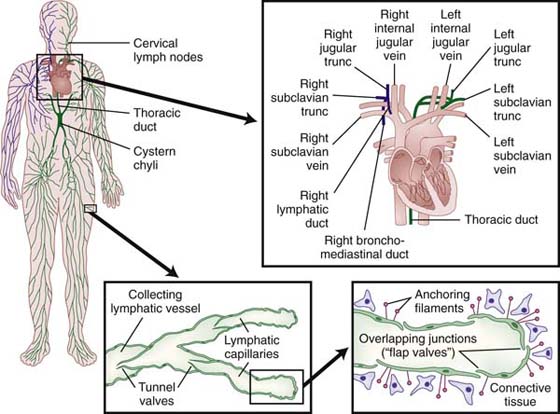

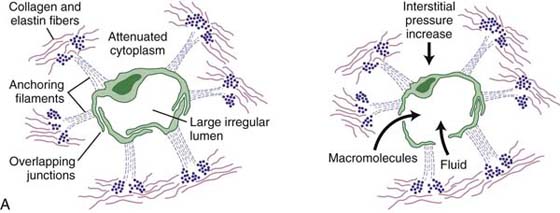

The lymphatic capillaries, the beginning of the lymphatic system, abound in the dermis at the dermal-epidermal junction, forming a flat, two-dimensional continuous network over the entire body with the exception of the central nervous system and cornea.3 Unlike blood capillaries that consist of continuous tubules of endothelial cells, lymphatic capillaries consist of overlapping endothelial cells (Fig. 64-1). A surrounding fiber net of anchoring filaments, arranged around the lymph capillaries, enables these vessels to stay open at the junction between the overlapping cells even under high tissue pressure4 (Fig. 64-2). The lymphatic loads are resorbed by the lymph capillaries and flow into larger lymph vessels called precollectors, which then drain into collectors. Lymph collectors have valves, spaced every 6 to 20 mm. Segments between two valves in a lymph collector are called lymph angions. The contraction of smooth muscle in each angion (called lymphangiomotoricity) generates the propulsive force of lymph flow along the lymph vessel. The frequency of contraction of lymph angions at rest is 6 to 10 contractions per minute.5 The propulsion directs the lymph fluid into regional and central lymph nodes to be filtered (Fig. 64-3). Ultimately, the lymph fluid empties into the venous system through the left and right venous angles, i.e., at the junctions between the subclavian and jugular veins at the level of the clavicles.

Figure 64-2 Anchoring filaments. A, A cross-section of lymph capillary showing how lymph fluid moves into the lymph capillary. B, The relationship of the lymphatic system with the circulatory system.

The amount of lymphatic load transported by the lymphatic system is dependent on the same forces that propel blood in the blood capillaries. Starling’s equation (Table 64-1) describes the balance or equilibrium of capillary filtration and reabsorption.4,6 The transport of fluid through the membrane of blood capillaries depends on four variables: blood capillary pressure, colloid osmotic pressure of the plasma proteins, colloid osmotic pressure of the proteins located in the interstitial tissue, and tissue pressure.

Table 64-1 Starling’s Equation: Jv = Kf [Pc − Pif − σ(πp − πif)]

Legend |

Definition |

Pc − Pif |

Hydrostatic pressure gradient |

πp − πif |

Colloid osmotic pressure gradient |

Kf |

Permeability of water and small solutes |

σ |

Permeability of plasma proteins |

Jv |

Capillary filtrate |

JL |

Lymphatic return |

Jv > JL |

Edema |

Ultrafiltration is defined as blood capillary pressure greater than the colloid osmotic pressure of plasma proteins. Reabsorption is defined by blood capillary pressure less than the colloid osmotic pressure of plasma proteins.4

A shift in Starling’s equilibrium toward an increase in ultrafiltration (such as occurs in cases of inflammation or venous hypertension) or decreased colloid osmotic pressure (associated with hypoproteinemia) can cause an increased amount of lymphatic load, placing a higher burden on the lymphatic system. A healthy lymphatic system is generally able to prevent or decrease the amount of acute edema. Under normal conditions, the transport capacity (TC) of the lymphatic system is approximately 10 times greater than the physiologic amount of the lymphatic loads. This is known as the functional reserve (FR) of the lymphatic system4 (Fig. 64-4). As long as the lymphatic load remains lower than the transport capacity of the lymphatic system, the lymphatic compensation is successful. If the lymphatic load exceeds the transport capacity, edema will occur. This is called dynamic insufficiency of the lymphatic system; the lymph vessels are intact but overwhelmed (Fig. 64-5). The result is edema, which can usually be successfully treated with elevation, compression, and decongestive exercises (any basic exercise to facilitate the muscle pump).4

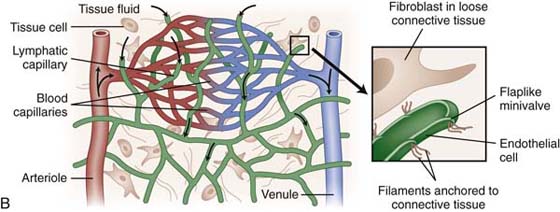

Lymphedema is caused by mechanical insufficiency or low-volume insufficiency of the lymphatic system. The transport capacity drops below the physiologic level of the lymphatic loads (Fig. 64-6). This means the lymphatic system is not able to clear the interstitial tissues, and an accumulation of high protein fluid is the result. This is recognized as lymphedema or lymphostatic edema.4 The decisive difference between lymphedema and virtually all other types of edema is the high content of plasma proteins in the interstitial fluid. Over time (several months to years), this can lead to fibrosis of all affected tissue structures and is readily evident in the texture and consistency of the involved integument7 (Fig. 64-7).

Figure 64-7 Skin changes with lymphedema. The image depicts dry skin, hyperkeratosis, fibromas, and papillomas. (The image above is a copyrighted product of Association for the Advancement of Wound Care [www.aawcone.org] and has been reproduced with permission.)

Sometimes the etiology of edema is uncertain, and there is no clear clinical distinction between lymphedema and other types of edema. Some swelling may be a mixture of both edema and lymphedema, as occurs when the functional reserve of the lymphatic system is exceeded and the lymph transport capacity is compromised.8 The progression of lymphedema from the first perception of “heaviness” by the patient and nonresolving edema to irreversible fibrotic changes takes time. In an effort to standardize the associated integumentary changes, staging and classification systems have been developed. The staging system is used clinically to describe the subjective and objective integument changes. The classification system is used for unilateral limb involvement and is based on circumferential limb measurements. Tables 64-2 and 64-3 show the stages and severity classification systems for lymphedema. Early accurate diagnosis, patient education, and appropriate treatment will decrease the amount of time needed to achieve limb reduction, skin changes, and overall improvement or restoration of function.3

Table 64-2 Stages of Lymphedema

Stage |

Description |

0 |

Latent or subclinical condition: swelling is not evident despite impaired lymph transport. |

I |

Reversible lymphedema: early accumulation of protein-rich fluid, elevation reduces swelling; tissue pits on pressure. |

II |

Spontaneously irreversible lymphedema: proteins stimulate fibroblast formation; connective and scar tissue proliferate; minimal pitting even with moderate swelling. |

III |

Lymphostatic elephantiasis: hardening of dermal tissues, papillomas of the skin, tissue appearance elephant-like. (Not everyone progresses to this stage.) |

Adapted from the International Society of Lymphology Consensus Document on Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Lymphedema, 2003.

Table 64-3 Severity of Lymphedema Stages

Classification |

Description |

Minimal |

<20% increase in limb volume |

Moderate |

20%–40% increase in limb volume |

Severe |

>40% increase in limb volume |

Adapted from the International Society of Lymphology Consensus Document on Diagnosis and Treatment of Peripheral Lymphedema, 2003.

The etiology of lymphedema is currently classified into two major categories: primary and secondary lymphedema. Primary lymphedema is caused by a condition that is either hereditary or congenital. In the United States, it is estimated that approximately 2 million people have primary lymphedema.9 Eighty-three percent of primary lymphedema cases manifest before the age of 35 (lymphedema praecox)10 and 17% manifest after the age of 35 (lymphedema tardum). The onset of primary lymphedema can occur at birth (Milroy’s disease or Meige’s syndrome), but most often the onset is during puberty or around the age of 17 years. Eighty-seven percent of all cases of primary lymphedema occur in females, and the lower extremities are more often involved than other body parts.11

Secondary lymphedema is caused by some identifiable insult to the lymphatic system.11 Secondary lymphedema etiologies include inflammation, infection, radiation therapy, surgery, filariasis (parasitic infection), trauma, iatrogenic alterations, artificial self-induced lymphedema, benign or malignant tumor growth, and chronic venous insufficiency.11 Approximately 2.5 to 3 million people in the United States have been diagnosed with secondary lymphedema.9 One third of patients who undergo mastectomy (with lymph node resection) secondary to breast cancer develop secondary lymphedema of the upper extremity (the reported incidence varies depending on study parameters).12 Radical lymph node dissection with prostate cancer causes lymphedema of one or both legs and often the genitals in more than 70% of the cases.13 Secondary lymphedema is usually unilateral; however, it may present in both limbs. It is important to note, however, that involvement of the limbs and presentation of the edema is generally not symmetrical. One limb will appear larger, and it is this limb that should be addressed first with respect to intervention strategies.

Lymphedema can lead to numerous health-related and emotional problems. Of concern is the high risk of infection and skin changes associated with chronic lymphedema, particularly for patients who do not receive appropriate intervention. Fluid accumulation in the tissues is an ideal medium for pathogen growth, and cellulitis and venous-type ulceration (particularly of the lower extremities) can be a common occurrence for patients with lymphedema. Patients also experience embarrassment and social barriers because of the increased limb size, discomfort, diminished movement and function of the affected limb or limbs, and difficulty donning and doffing clothing, each of which may compromise a person’s quality of life.8

(Adapted from Linda T. Miller, Management of Breast Cancer Related Edemas, 5th Edition).

Although lymphedema can occur at any time after treatment for breast cancer,14 postoperative edema, often called acute lymphedema, occurs within the first 6 weeks after breast cancer surgery. Mild postoperative edema and subtle changes in tissue are expected and often transient, resolving with the healing of the surgical site and lymphatic regeneration.15 Often, therapeutic interventions such as simple active range of motion (ROM) exercises and appropriate positioning may be all that is necessary to assist in resolving the edema. Any individual who undergoes axillary, breast, or chest surgery is considered to be at risk for the development of lymphedema in the trunk quadrant and upper extremity of the affected side. Patient education about the signs and symptoms of lymphedema as well as proper management and protection of the limb at risk should be implemented.

At approximately 2 to 3 weeks after the axillary dissection, many patients will experience pain along the anteromedial aspect of the involved upper extremity,16 which appears to follow a neurovascular pattern. Cordlike, superficial, fibrous bands usually develop, which are often visible and palpable, especially through the anterior elbow and ventral forearm. Pain associated with cording, also known as sclerosing lymphangitis,16,17 is often described as a “drawing” or “pulling” feeling, which extends from the axilla to the fingers. Shoulder flexion with the elbow extended becomes increasingly difficult because of tightness of the cords.

These cordlike bands usually soften and often disappear at approximately 8 to 12 weeks. However, mild moist heat applied to the outstretched arm, followed by gentle, skillful stretching of the cords and soft tissue, can provide a dramatic decrease in pain and increase in ROM in only a few therapy sessions.

Often, cording-related edema is most noticed initially in the ventral forearm and radial hand and is commonly described as “painful,” fitting the pain pattern as described previously. This edema frequently presents during the first 3 months postoperatively but can appear with the same signs and symptoms years later and usually corresponds to some traumatic irritation of the sclerosed lymphatic vessels, such as a quick stretch of the arm or an attempt to lift something that is too heavy.

Edema that presents with cording as its underlying cause must be treated concurrently with the cording. Manual therapy, including gentle passive ROM of the shoulder with elbow and wrist extension and mild skin traction, can be followed by the appropriate edema techniques. When treated early and appropriately, cording-related edema usually resolves.

Edema of the arm or adjacent trunk may develop in patients undergoing certain chemotherapy regimens. Corticosteroids such as dexamethasone and glucocorticoids may cause short-term fluid retention throughout the body.18,19 Because of the axillary dissection, drainage from the ipsilateral lymph vessels may be impaired. Any increase in fluid in the compromised area can tip the balance in favor of an edematous condition.

At the first sign of edema, management techniques should be initiated. Treatment success may be hampered as long as the patient continues to receive chemotherapy. However, once chemotherapy is concluded, the edema can resolve with continued treatment.

Emphasis must be placed on early detection and treatment of these acute edemas. They often will resolve with skillful, early intervention. However, if allowed to progress, even these early edemas can go on to become chronic conditions.

Lymphedema occurs between the deep fascia and the skin. In addition to a decrease in lymphatic transport capacity, there is also a decrease in macrophage activity and an increase in the action of fibroblasts.20,21 The accumulating protein creates an environment for chronic inflammation and progressive fibrosis of the tissues. Fibrosis of the initial lymphatic vessels and collectors leads to a failure of the endothelial junctions to close and valvular dysfunction in the deeper collecting vessels. This results in the failure of the vessels to remove proteins from the interstitium.22 As the condition progresses, protein continues to accumulate, forming a network of fibrosclerotic tissue.

Other histologic changes, such as deep fascial thickening, occur as edema progresses. Changes such as circumference and tissue texture can easily be detected and documented. However, before the development of such obvious symptoms, an increase in the infection rate (recurrent cellulitis) may indicate an impending lymphedema.20,21

A thorough physical examination and clinical history are essential in correctly diagnosing lymphedema and thereby choosing the appropriate interventions.23 The diagnosis of lymphedema is made in most cases by patient history, systems review, inspection, palpation, and a few select noninvasive tests such as volume or girth measurement. Diagnosis of upper extremity lymphedema is usually evident, especially with a history of axillary, breast, or chest surgery. At present, the only clinical test that has been shown to be a reliable and valid method to diagnose lymphedema is Stemmer’s sign.24,25 This is a thickening of the skin over the proximal phalanges of the toes or fingers of the involved limb and the inability to “tent” or pick up the skin (Fig. 64-8).

Figure 64-8 Stemmer’s sign. (The image above is a copyrighted product of the Association for the Advancement of Wound Care [www.aawcone.org] and has been reproduced with permission.)

If the result is positive, it is a definite indication of lymphedema; if it is negative, lymphedema might still be present, but not yet advanced enough to cause Stemmer’s sign.26 When Stemmer’s sign is absent, it is appropriate to treat the edema with conventional interventions of elevation, rest, and compression. If the edema does not respond to conventional interventions, it should be monitored and regular reassessment should be conducted because the underlying pathology may be early lymphedema.

A thorough history is essential to correctly identify lymphedema. The history should include the following:

• Onset of the symptoms (swelling, heaviness of limb), length of time since initial onset, and the triggering event (i.e., a bee sting, sprained wrist, recent surgery or trauma) if known.

• Medical history including traumatic events and surgery. This should also include all current medications, health risk factors, and coexisting problems (i.e., cancer diagnosis, obesity, cardiac problems, venous insufficiency), and family history.

• Pain and/or associated discomfort. Significant pain may suggest additional tests and measures to determine whether a secondary problem exists such as venous or arterial compromise and an underlying orthopedic condition. Most patients with lymphedema report heaviness and associated discomfort in lieu of pain because of the large amounts of fluid in the tissues.

• Functional status and activity level. Does the patient report a loss in function or difficulty performing activities of daily living because of the swelling? How active or inactive is the patient and what type of activities does he or she enjoy and/or participate in?

• Review of social habits such as smoking, diet and nutritional habits, and physical fitness/weight management strategies. A diet does not exist for lymphedema, but a low-sodium diet in combination with good hydration and nutritional habits is recommended.27

• Treatment and intervention history. Some interventions may have led to an exacerbation of the symptoms, such as improper compression, sole use of a pneumatic compression pump, thermal modalities, and/or deep massage.28

After the history, a brief systems review should be performed. Specifically, a review of the cardiopulmonary, integumentary, musculoskeletal, and neuromuscular system will help the clinician to identify health problems that may require referral to another health professional, and it may help to identify specific tests and measures to use to complete a thorough patient assessment. In addition, it is important to review the patient’s affect, cognition, language, and learning style to optimize the examination and intervention strategies.

Tests and measures that should be included for patients with lymphedema or those at risk of the development of lymphedema follow.29 Characteristic findings common with lymphedema include the following:

• Integumentary integrity. Extensive palpation and inspection including texture (rough, orange peel–like), color (red, brown, darker than person’s natural color), pitting status (slow or hard to pit), fibrosis (hardening of the skin and tissues), temperature (involved limb may feel warmer on palpation), deepening of skin folds (skin may fold over wrist joint similar to a rubber band effect), nail quality (thickened and/or discolored), Stemmer’s sign, and presence of cysts/fistulae, papillomas, or ulcers (defects in the integument such as lesions and benign growths).

• Anthropometric characteristics. Volume measurements using water displacement and girth measurements comparing circumferential limb segments of the involved and noninvolved limbs are the most common noninvasive assessments of the lymphedematous limb.30 If the involvement is bilateral, baseline measurements should be taken of both limbs for future comparison. Tonometry (measurement of fluid mobility by recording the tissue deformation) and bioelectrical impedance analysis (amount of extracellular water and total water content) are newer methods that can assist with detecting subclinical lymphedema.31,32

• Joint integrity and mobility, muscle performance, ROM, and posture. Patients with lymphedema can present with significant limitations on manual muscle testing and goniometry because of the heaviness of the limb from the excessive fluid burden. Biomechanical compensations and overuse of the noninvolved limb can negatively affect joints and posture.

• Pain. Pain should be differentiated from discomfort or heaviness. The location is important to determine whether the pain is related to the lymphedema or another problem. The use of a Visual Analogue Scale can objectify the patient’s pain response and help to differentiate pain from discomfort. Pain may be related to other patient co-morbidities (i.e., peripheral vascular disease, orthopedic or neuromuscular pathologies), or it could be an indicator of infection (i.e., cellulitis). Further evaluation should explore the true nature of the pain so that the appropriate intervention can be implemented.

• Arousal, mentation, and cognition. These are important because patient education and compliance are paramount for successful management. Patients require extensive education and support to learn how to manage lymphedema and how to prevent exacerbations and/or associated complications. Verbal instruction, demonstration, and patient-appropriate literature will help to empower patients with lymphedema.

• Ventilation, respiration, and circulation. A pulmonary review (part of the systems review) will determine the patient’s tolerance to deep breathing and resisted breathing, which are components of lymphedema intervention.

• Sensory and reflex integrity. These are particularly important with associated complications such as diabetes and circulatory disorders so as to recognize and prevent further injury.

• Motor function. Establishing the patient’s functional baseline will promote individualized exercise prescription, aiding in compliance and positive outcomes. In clinical practice, it seems that the larger the lymphedematous limb is, the more common and advanced the compensations and impairments present in fine and gross motor skills.

• Orthotic, prosthetic, supportive devices, assistive and adaptive devices. Identification of need will assist with the rehabilitation and prevention components of treatment by improving safety and facilitating independence.

• Aerobic capacity and endurance. Establishing baseline will promote individualized exercise prescription, thus assisting with compliance and improved outcomes.

• Self-care and home management. It is imperative to determine the needs of the patient to effectively implement treatment interventions. The patient’s ability or lack of ability to participate will directly affect the course of care, particularly self-management of lymphedema.

• Community and work/school integration or reintegration and environmental, home, and work/school barriers. Patient and family education, modification of lifestyle, and maintenance and prevention strategies should consider the patient’s home and work/school life for optimal results.28

Meticulous skin and nail care is a significant part of lymphedema intervention and prevention. The goal is to prevent skin breakdown and infection. However, many patients present with skin lesions because of the destructive nature of chronic lymphedema and the excessive fluid burden on the tissues. The excess fluid commonly associated with chronic lymphedema increases the diffusion distance and the distance that oxygen, nutrients, and blood are required to travel from the capillaries to the cells and tissues of the skin. A high fluid burden on the tissues could also result in systemic infection because stagnant fluid is present for pathogen growth. Tissue lesions common with lymphedema, caused by the impaired lymph vascular system and/or other co-morbid conditions, may present from simple superficial excoriations to multifarious ulcers with complex etiologies. Vascular and inflammatory ulcers, fungating wounds, radiation burns, minor traumas, and failed surgical sites are all potential skin lesions that may present in patients with lymphedema.

If wounds are present on a lymphedematous limb, lymph drainage and compression can help to decrease the severity of the ulceration.1 Appropriate wound management combined with specific lymph drainage around the ulcer helps to rid the wound of cellular debris and toxins.5 Care should be taken to drain the fluid away from the ulcer to prevent wound congestion, and additional drainage techniques should be used on the proximal extremity to promote the lymphatic flow toward regional lymph nodes. (Specific drainage techniques are discussed in the section on lymphedema interventions.)

Cellulitis is the most common complication of primary and secondary lymphedema. Cellulitis is a painful inflammation of the soft tissue that is characterized by expanding local erythema, palpable local lymph nodes in 50% of the cases, and associated fever and chills.13 Caused by an acute Streptococcus infection, the smallest injuries can be the portal of entry for the bacteria, leading to a local or systemic infection. Seventy percent of cellulitis cases are caused by simple injuries such as cuts, abrasions, insect bites, local burns, and interdigital mycosis.13 Treatment requires local antibiotics and/or persistent systemic antibiotic therapy in addition to patient education about preventive measures because recurrence is frequent, thereby further limiting lymph transport capacity.13

Local wound infection is common because the moist/wet environment is conducive to pathogen growth. Treatment involves addressing the underlying infection, if present, with appropriate systemic and topical antibiotics. Local wound care should involve managing the oftentimes copious exudate while maintaining adequate compression. Hydrofibers, alginates, and other absorptive dressings should be considered in the presence of exudating wounds. Four-layer bandage systems (e.g., Profore, Smith & Nephew, Largo, FL; and Dyna-Flex, Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ) are effective for absorbing excess drainage and provide the necessary and vital compression. With compression and control of lymphedema, the associated wounds will heal in the majority of cases.1 Once the systemic and/or local infection has resolved, specific lymphedema interventions (manual lymph drainage, compression, exercise, and skin and nail care) should begin or resume.

Compression is the cornerstone of lymphedema therapy. The degree of swelling and the presence of skin breakdown, diabetes, arterial insufficiency, and chronic congestive heart failure must be considered.1 Short-stretch bandages, long-stretch bandages, cotton padding, self-adherent crepe dressings, and combination wraps are among the various compression bandages used in the treatment of lymphedema. In applying compression, frequently reassessing the condition of the limb (i.e., limb size reduction) and matching the dressing to the patient’s diagnosis and wound status is critical.1

With respect to compression, bandages differ in elasticity and extensibility. Bandages also have varying amounts of resting and working pressure. Resting pressure is pressure exerted on the skin by the elastic when put on stretch, whether the patient is moving or activating a muscle pump. Working pressure is pressure exerted on the skin when contracting muscles push against a compression bandage. Short-stretch bandages have a high working pressure and low resting pressure. Short-stretch bandages (e.g., Comprilan, BSN-Jobst, Inc., Charlotte, NC) stretch 20% of their original length compared with long-stretch bandages (e.g., Ace wraps) that stretch up to 190% of their original length. When the limb is at rest, short-stretch bandages supply a comfortable degree of support (without a tourniquet effect), but the total pressure increases significantly when the muscles contract against fixed resistance. This creates an effective, intermittent massage that forces interstitial fluid into functioning lymph collectors. Therefore, the compression wrap becomes a dynamic part of the wound dressing or treatment for patients with lymphedema.1

Once the diagnosis of lymphedema has been made, it is essential that the appropriate interventions be used to address the patient’s impairments. Treatment should involve specific interventions for lymphedema, integument management strategies, and rehabilitation for functional impairments. Long-term management requires prevention and maintenance strategies to decrease the risk of exacerbations, infections, and other associated impairments.

Lymphedema is a manageable disease with the appropriate treatment and intervention. The goal of lymphedema therapy is to get the patient back to a subclinical or latency stage, regardless of his or her diagnosed stage or classification. In most cases, this can be readily achieved with complete decongestive therapy (CDT). CDT is a two-phase intervention for lymphedema that is noninvasive, highly effective, and cost-effective that can reduce and maintain limb size.33-35 The proposed benefits of CDT include opening collateral lymphatic drainage pathways, increased pumping by the deep lymphatic pathways, and a reduction and breakdown of fibrotic tissue.23,34

Phase I, or the intensive phase, involves meticulous skin and nail care, manual lymphatic drainage (MLD), bandaging, exercise (in bandaging), and the use of a compression garment (at the end of phase I). Phase II, or the self-management phase, involves the patient wearing a compression garment during the day, bandaging at night, exercise (in the garment or bandage), meticulous skin and nail care, and self-MLD as needed.35

MLD is a specialized manual technique based on the physiologic principles of lymph flow and lymph vessel emptying. MLD affects the lymph system by moving lymph fluid around blocked areas toward collateral vessels, anastomoses, and uninvolved lymph node regions; increasing lymph angiomotoricity; increasing the volume of transported lymph fluid; increasing pressure in the lymph collector vessels; improving lymph transport capacity; and potentially increasing arterial blood flow.34,36-42

In Europe, phase I of CDT includes twice-daily visits for an average of 4 to 6 weeks. In the United States (because of health-care constraints), CDT is limited to daily visits for 3 to 4 weeks for the upper extremity and 4 to 6 weeks for the lower extremity.35 Phase II begins when phase I ends (a plateau in limb reduction as indicated by weekly girth measurements) and may continue for as long as 18 months after CDT initiation. The duration and intensity of treatment depend on the clinical stage of lymphedema. Stages I and II (mild and moderate lymphedema) are more easily managed than stage III (severe lymphedema). Patient compliance is paramount, and management is a lifelong process. The stages and classifications help health-care professionals to determine the intensity of the therapy as well as plan the potential duration of the interventions.

Functional limitations should be addressed according to patient needs. Often, as the limb(s) reduces in size, function is improved. However, patients often require basic exercise prescription to improve strength, flexibility, and cardiovascular health.

Several other interventions are worthy of discussion as they are often implemented for the management of edematous and lymphedematous limbs. These include intermittent compression pumps, diuretics, and physical agents.

Intermittent pneumatic compression pumps can be harmful to patients with lymphedema when they are used inappropriately. These pumps successfully mobilize fluid; however, proteins may remain in the affected tissues. This can promote more fluid to accumulate because proteins are hydrophilic, causing the area to become even more fibrotic. If a pump is used without MLD, the mobilized fluid may collect in the torso from the upper extremity or in the groin area from the lower extremities. The pumps do not reroute lymph fluid, as does MLD. It is highly recommended to only use a pump at the end of phase II of CDT in combination with MLD. The pump should not be used to decongest, but to maintain the benefits of CDT.

A second treatment consideration is the use of diuretics. Diuretics also mobilize fluid out of the affected areas and increase the blood volume. The proteins, however, remain in the affected tissues, drawing in more water, which ultimately leads to more fibrosis. Some patients may have co-morbidities that require the use of diuretics, such as congestive heart failure, certain kidney disorders, or high blood pressure. As long as the physician is managing the patient for the specific condition that requires a diuretic, then the diuretic should be continued. If the diuretic is solely being used to manage lymphedema, it is important to discuss other treatment options such as CDT with the physician and suggest that the diuretic be discontinued.

Patients must be educated about the risk reduction practices and risk factors as currently understood. Patients must also avoid activities that can cause a further decrease of the transport capacity of the lymph vessels or unnecessarily increase the lymphatic fluid and protein load of the lymphatic system in an affected region.28

Patients should be properly educated regarding exercise and activities of daily living that are safe and beneficial for them to perform. The goal of exercise is to improve lymphatic flow without adding undue stress on the impaired lymphatic system. Exercise programs should be prescribed and progressed at a pace to ensure compliance and where the effects of the exercise can be monitored and altered if required. Individual exercise programs should be adjusted to the patient’s fitness level and directed by a therapist or clinician with knowledge on exercise progression, lymphedema contraindications, and risk factors.

Risk reduction strategies and adherence to maintenance programs are essential to decrease the risk of exacerbation and/or injuries that can lead to infection and subsequent lymphedema.

The National Lymphedema Network (NLN) published a Position Statement of Lymphedema Risk Reduction Practices in 2006.43 The recommendations published in this position statement are listed below with express permission by the NLN to reprint the content.

1. Skin care: avoid trauma/injury to reduce infection risk.

a. Keep extremity clean and dry.

b. Apply moisturizer daily to prevent chapping/chafing of skin.

c. Attention to nail care; do not cut cuticles.

d. Protect exposed skin with sunscreen and insect repellant.

e. Use care with razors to avoid nicks and skin irritation.

f. If possible, avoid punctures such as injections and blood draws.

g. Wear gloves while doing activities that may cause skin injury (i.e., washing dishes, gardening, working with tools, using chemicals such as detergent).

h. If scratches/punctures to skin occur, wash with soap and water, apply antibiotics, and observe for signs of infection (i.e., redness).

i. If a rash, itching, redness, pain, increased skin temperature, fever, or flulike symptoms occur, contact your physician immediately for early treatment of possible infection.

a. Gradually build up the duration and intensity of any activity or exercise.

b. Take frequent rest periods during activity to allow for limb recovery.

c. Monitor the extremity during and after activity for any change in size, shape, tissue, texture, soreness, heaviness, or firmness.

a. If possible, avoid having blood pressure taken on the at-risk extremity.

b. Wear loose-fitting jewelry and clothing.

a. They should be well fitting.

b. Support the at-risk limb with a compression garment for strenuous activity (i.e., weight lifting, prolonged standing, running) except in patients with open wounds or with poor circulation in the at-risk limb.

c. Consider wearing a well-fitting compression garment for air travel.

a. Avoid exposure to extreme cold, which can be associated with rebound swelling or chapping of skin.

b. Avoid prolonged (longer than 15 minutes) exposure to heat, particularly hot tubs and saunas.

c. Avoid placing limb in water temperatures above 102°F (38.9°C).

6. Additional practices specific to lower extremity lymphedema

a. Avoid prolonged standing, sitting, and crossing legs.

b. Wear proper, well-fitting footwear and hosiery.

c. Support the at-risk limb with a compression garment for strenuous activity except in patients with open wounds or with poor circulation in the at-risk limb.

Note: Given that there is little evidence-based literature regarding many of these practices, the majority of the recommendations must at this time be based on the knowledge of pathophysiology and decades of clinical experience by experts in the field.

Lymphedema can significantly affect a patient’s functional status and quality of life. Because lymphedema is a progressive disease, early intervention and identification of the disease are important to improve patient outcomes. Once limb reduction has been achieved with CDT, associated functional limitations should be addressed.

Because of the significant size of some lymphedematous limbs, patients often have difficulty with activities of daily living. Involvement of the upper extremity can often affect gross and fine motor skills involving the phalanges, wrist, elbow, and shoulder, rendering basic skills difficult, if not impossible. Additionally, patients often are deconditioned and have limited cardiovascular endurance. Initiating CDT to reduce limb size will facilitate improvements in function and activities of daily living. Providing patients with appropriate assistive devices will enhance safety and reduce complications related to biomechanical compensations. Basic exercise prescription for cardiovascular endurance and strengthening will provide overall improvement in mobility tasks and enhance home and community skills.

Other impairments associated with lymphedema include limitations in ROM (because of large fluid volumes), decreased strength (related to diminished use), and difficulty with upper extremity function and activities of daily living when the lymphedema is present in the hand and/or arm. ROM should improve as limb volume decreases. Individualized exercise prescription including ROM and therapeutic exercise will improve function by restoring range and strength for both fine and gross motor activities. Compliance with exercise prescription is improved if activities are broken down into short-duration yet frequent sessions throughout the day. In addition, lifestyle modifications and adherence to compression therapy will augment functional outcomes.

Lymphedema is often referred to as a hidden epidemic; however, it is a manageable disease. Identification and intervention at any stage can improve functional and cosmetic outcomes. Recognizing and addressing the associated impairments related to lymphedema will enhance outcomes and patient satisfaction. Additionally, patient education and compliance with treatment is paramount for the successful management of this disease.

1. Macdonald JM. Wound healing and lymphedema: a new look at an old problem. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2002;47(4):52–57.

2. Casley-Smith JR, Casley-Smith JR. Frequency of lymphedema. In: Casley-Smith JR, Casley-Smith JR, eds. Modern Treatment for Lymphoedema. Malvern: The Lymphedema Association of Australia; 1997:81–84.

3. Kelly D. Anatomy and Physiology of the Lymphatic System with Clinical Implications. A Primer on Lymphedema. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2002. 3-27

4. Zuther J. Understanding lymphedema. PT & OT Today. 1997.18–22.

5. Weissleder H, Schuchhardt C. Physiology. In: Weissleder H, Schuchhardt C, eds. Lymphedema Diagnosis and Therapy. Koln: Viavital Verlag; 2001:25–34.

6. Kramer GC, Lund T, Herndon D. Pathophysiology of burn shock and burn edema. In: Herndon D, ed. Total Burn Care. New York: W.B. Saunders; 2002:78–87.

7. Weissleder H, Schuchhardt C. Pathophysiology. In: Weissleder H, Schuchhardt C, eds. Lymphedema Diagnosis and Therapy. Koln: Viavital Verlag; 2001:35–48.

8. Weiss J, Spray B. The effect of complete decongestive therapy on the quality of life of patients with peripheral lymphedema. Lymphology. 2002;35:46–58.

9. Chikly B. Lymphedema: An Overview. Silent Waves: Theory and Practice of Lymph Drainage Therapy. Scottsdale: International Health & Healing; 2001. 168-170

10. Casley-Smith JR. Alterations of untreated lymphedema and its grades over time. Lymphology. 1995;28(4):174–185.

11. Kelly D. Lymphedema. A Primer on Lymphedema. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2002. 29-41

12. Weissleder H, Schuchhardt C. Primary lymphedema. In: Weissleder H, Schuchhardt C, eds. Lymphedema Diagnosis and Therapy. Koln: Viavital Verlag; 2001:98–117.

13. Weissleder H, Schuchhardt C. Secondary lymphedema. In: Weissleder H, Schuchhardt C, eds. Lymphedema Diagnosis and Therapy. Klon: Viavital Verlag; 2001:118–246.

14. Petrek JA, Heelan MC. Incidence of breast carcinoma–related lymphedema. Cancer. 1998;83(Suppl):2776.

15. Cooley ME, Erikson B. Rehabilitation. In: Fowble B, ed., et al. Breast Cancer Treatment: A Comprehensive Guide to Management. St Louis: Mosby; 1991.

16. Wood C, Gerber L. Rehabilitation of the patient with breast cancer. In: Lippman M, ed., et al. Diagnosis and Management of Breast Cancer. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1988.

17. Ryan TJ, Mortimer PS, Jones RL. Lymphatics of the skin: neglected but important. Int J Dermatol. 1986;25:411.

18. Giani L, Capri G. New chemotherapy drugs. In: Bonadonna G, Hortobagyi GN, Gianni AM, eds. Textbook of Breast Cancer. London: Martin Dunitz; 1997.

19. Ogawa M, Ariyoshi Y. Supportive care: chemotherapy-induced emesis and cancer pain. In: Bonadonna G, Hortobagyi GN, Gianni AM, eds. Textbook of Breast Cancer. London: Martin Dunitz; 1997.

20. Mortimer PS. Managing lymphedema. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:98.

21. Piller NB. Gaining an accurate assessment of the stages of lymphedema subsequent to cancer: the role of objective and subjective information when to make measurements and their optimal use. Eur J Lymphol. 1999;7:1.

22. Piller NB. Pharmacological treatment of lymph stasis. In: Olszweski WL, ed. Lymph Stasis: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1991.

23. Rockson SG. Workgroup III. Diagnosis and management of lymphedema. Cancer. 1998;83(12):2882–2885.

24. Stemmer R. Ein Klinisches Zeichen Zur Fruhund Differential Diagnose Des Lymphoedemas [A clinical sign for the differential diagnosis of lymphedema]. Vasa. 1976;5:261–262.

25. Foldi E. Uber Das Stemmersche Zeichen [About the Stemmer sign]. Vasomed. 1997;9(187):189.

26. Casley-Smith JR, Casley-Smith JR. Diagnosis of lymphedema and implications for treatment. In: Casley-Smith JR, Casley-Smith JR, eds. Modern Treatment for Lymphedema. Malvern: The Lymphedema Association of Australia; 1997:94–97.

27. Zuther J. Lymphedema Management. New York: Thieme; 2005. 72

28. Kelly D. Patient Management. A Primer on Lymphedema. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2002. 45-62

29. Guide to physical therapist practice. Model definition of physical therapy for state practice acts. Physical Ther. 1997;77(11):1178.

30. Stanton AB, Badger C, Sitzia J. Non-invasive assessment of the lymphedematous limb. Lymphology. 2000;33:122–135.

31. Chen HC, O’Brien McC, Pribaz JJ, Roberts AN. The use of tonometry in the assessment of upper extremity lymphoedema. Br J Plastic Surg. 1988;41:399–402.

32. Cornish BH, Chapman M, Hirst C, et al. Early diagnosis of lymphedema using multiple frequence bioimpedance. Lymphology. 2001;34:2–11.

33. Boris M, Weindorf S, Lasinski G. Lymphedema reduction by noninvasive complex lymphedema therapy. Oncology. 1994;8:95–106.

34. Hwang JH, Kwon JY, Lee KW, et al. Changes in lymphatic function after complex physical therapy for lymphedema. Lymphology. 1999;32(1):15–21.

35. Kelly D. Complete Decongestive Therapy. A Primer on Lymphedema. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; 2002. 65-99

36. Franzeck UK, Spiegel I, Fischer M, et al. Combined physical therapy for lymphedema evaluated by fluorescence microlmyphography and lymph capillary pressure measurements. Vasc Res. 1997;34:306–311.

37. Foldi E, Foldi M, Clodius L. The lymphoedema chaos: a lancet. Ann Plast Surg. 1989;22:505–515.

38. Casley-Smith JR. Varying total tissue pressures and the concentration of initial lymphatic lymph. Microvasc Res. 1983;25:369–379.

39. Mortimer PS, Simmonds R, Rezvani M, et al. The measurement of skin lymph flow by isotope clearance reliability, reproducibility, injection dynamics and the effect of massage. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;95(6):677–682.

40. Olszewski WL, Engeset A. Intrinsic contractility of prenodal lymph vessels and lymph flow in human leg. Am J Physiol. 1980;239(6):H775–H783.

41. Smith A. Lymphatic drainage in patients after replantation of extremities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79:163–168.

42. Eliska O, Eliskova M. Are peripheral lymphatics damaged by high pressure manual massage? Lymphology. 1995;28:21–30.