Chapter 26 Enteral Nutrition

Nutritional assessment

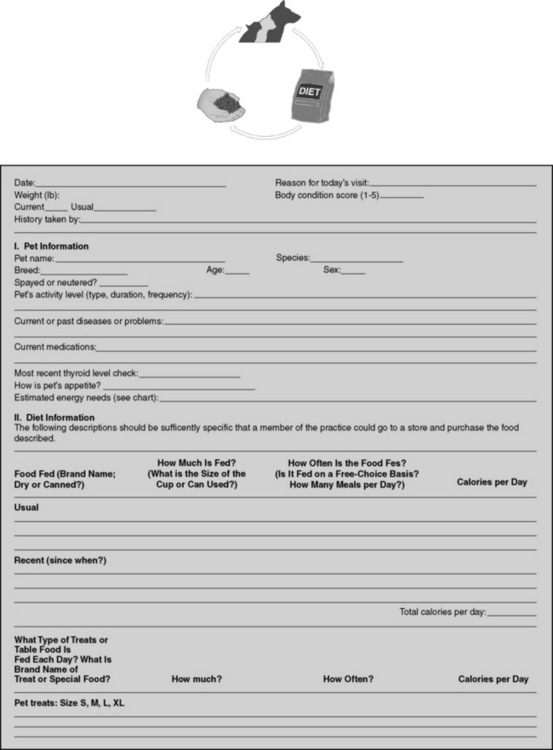

Identification of patients needing nutritional support requires a thorough history, physical examination, and evaluation of laboratory data. A diet history is obtained to ascertain the quality, total daily intake, and appropriateness of the diet fed (Figure 26-1). Identify current drugs the animal may have been prescribed (e.g., corticosteroids, antibiotics, diuretics, cancer chemotherapeutic agents), as these drugs can affect nutritional homeostasis. To assess the need for nutritional support, the medical history includes inquiries about: involuntary weight loss, voluntary dietary intake, and presence of persistent gastrointestinal signs. Historical information suggestive of malnutrition includes rapid weight loss (greater than 10% of usual body weight); recent surgery or trauma; and increased nutrient losses from wounds, vomiting, regurgitation, diarrhea, or burns. Infection, trauma, burns, and surgery can increase nutrient needs, whereas prolonged use of antinutrient or catabolic drugs may result in nutrient depletion. The number of days an animal has not consumed adequate calories (hyporexia or complete anorexia) before hospitalization may be determined from the history.

Figure 26-1 Diet history form.

(From Buffington T, Holloway C, Abood S. Manual of veterinary dietetics. St Louis: Elsevier, 2004.)

Physical evaluation begins with the assignment of a body condition score,14 ranging from 1 (cachexic) to 5 (obese), with 3 being normal (Table 26-1). Other scoring systems have been developed for dogs and cats.59,60 Underweight and malnourished animals often have a body condition score less than 3 out of 5 because of loss of muscle mass and subcutaneous fat. Thin, dry skin, hair that is easily epilated, pressure sores, and poor wound healing may be seen, indicating the body has redirected its nutrient resources to support visceral protein synthesis at the expense of peripheral tissues.

Table 26-1 Body Condition Score

| Score | Classification | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cachexic | Severely underweight, decreased muscle mass, no subcutaneous fat present, skeleton prominent. |

| 2 | Thin | Muscle mass adequate, little subcutaneous fat, skeleton apparent but not prominent. |

| 3 | Normal | Muscle mass adequate, ribs not seen but easily felt, obvious waist present when viewed from lateral or dorsoventral aspect. |

| 4 | Overweight | Individual ribs and spinous processes of vertebrae palpable only with moderate pressure, obvious fat pads present. |

| 5 | Obese | Palpation gives feeling of extensive fat cover over body. Large fat pads, respiratory and/or locomotor compromise. |

In patients with a condition score greater than 3 out of 5, the possibility that an “overcoat syndrome” has developed must be considered. Because metabolic changes associated with critical illness cause lean body mass to be broken down more quickly than adipose tissue, the body condition may appear normal when an overcoat of fat is covering a malnourished animal. These patients usually can be recognized by their poor hair coat quality, abnormal prominence of the bones of the head, and by palpation.

Many biochemical and hematologic abnormalities may occur during prolonged anorexia,62 including hypoalbuminemia, lymphopenia, and anemia, but they are not specific “markers of malnutrition.” Serum albumin concentration often is decreased in patients secondary to increased permeability of the vascular endothelium, as well as to decreased synthesis (or increased degradation) rates. Serum albumin concentration also is affected by hydration status and the presence of gastrointestinal, hepatic, or renal disease.51 Lymphopenia caused by malnutrition, stress, or immunosuppressive drugs. Starvation may interfere with immune competence even when the total lymphocyte count remains within the normal range.21

The main objective of nutritional assessment is to identify malnutrition as an independent problem. If not present initially, the animal should be periodically reevaluated during hospitalization to ensure that malnutrition does not develop secondary to an ongoing disease process, drug therapy, inability to eat, inappetence, or food deprivation.15 Nutritional support should be instituted in malnourished patients and in those for which voluntary food intake is impossible for prolonged periods.2

Evidence for early enteral nutrition

Numerous studies in human medicine have demonstrated multiple benefits to the early initiation of enteral nutrition (EEN), including improved gut barrier function, decreased bacterial translocation, and reduced septic complications and disease severity.* Early enteral nutrition in human medicine is defined as initiation of nutritional therapy within 48 hours of either hospital admission or surgery and is the standard of care.29 ASPEN guidelines recommend (Grade C) that enteral feedings should be initiated early within the first 24 to 48 hours following admission and advanced toward goal feeds over the next 48 to 72 hours in humans.70 In critically ill patients, nutritional support should commence as soon as the patient is hemodynamically stable, since many of these patients are already in a catabolic state. Although EEN remains controversial in dogs with acute pancreatitis, positive effects associated with EEN have been demonstrated in dogs diagnosed with parvoviral enteritis. Mohr, et al. randomized dogs with parvoviral enteritis into 2 groups: 15 dogs received no food until vomiting had stopped for 12 hours, and 15 dogs received early EN by nasoesophageal tube from 12 hours after admission.75 The EEN group demonstrated clinical improvements and had faster weight gains.75 Some veterinary nutritionists recommend nutrition support be instituted for any veterinary patient that is anorexic or anticipated to be hyporexic for longer than 3 days.

Nutrient needs

Dogs and cats that are eating require 50 to 100 mL of water per kilogram of body weight for daily maintenance, depending on environmental temperature, type of food, and amount of activity. Water requirements of normal fasting animals are only 5 to 10 mL/kg body weight per day (10% of the requirement of animals that are eating).83 This is because the solute load ingested with the diet and ultimately excreted by the kidneys is reduced.103

In sick animals, increased water losses via the urine may occur in some settings (e.g., diabetes mellitus, polyuric renal failure, hyperadrenocorticism, hyperthyroidism). Water also is lost in vomitus, diarrhea, burns, or hemorrhage. Insensible water losses (e.g., respiratory, cutaneous, fecal) may account for 20% to 40% of total water loss,5 which may be increased in the presence of fever, hyperventilation, hypermetabolism (e.g. sepsis), third-spacing of fluids and burn wounds.

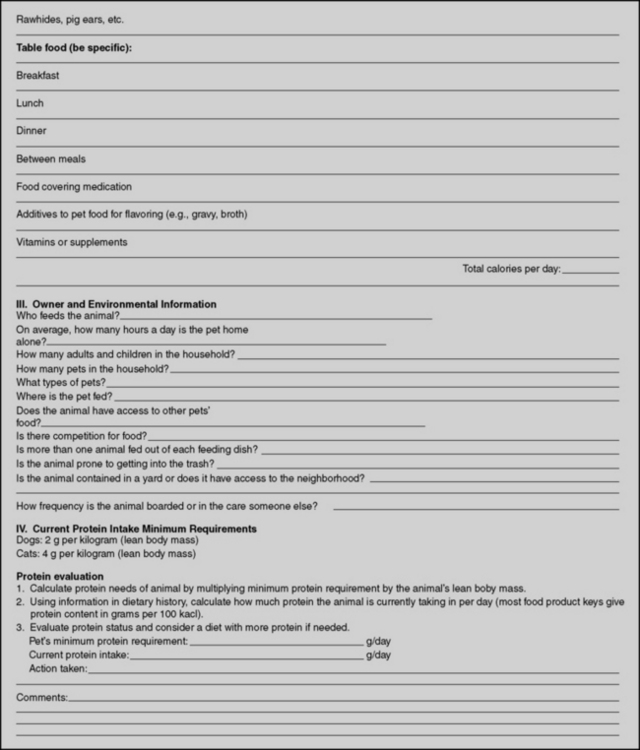

Energy needs of anorexic patients are estimated by summing requirements for basal metabolic functions, activity, and the effects of disease. Basal metabolic rate (calories per day required for protein turnover and maintenance of ionic gradients across semipermeable membranes) is usually estimated by exponential method:3,46,54 97 x BWkgO.655 (Figure 26-2) or 70 x BWkgO.75. A linear method (30 x BWkg + 70) should only be used for animals weighing between 2 to 45 kilograms.46

Figure 26-2 Approximate basal energy needs of dogs and cats.

(From Abood SK, Mauterer JV, McLoughlin MA, Buffington CA. Nutritional support of hospitalized patients. In: Slatter DH, editor. Textbook of small animal surgery, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1993.)

We estimate the energy needs of our patients by assuming that those resting in a hospital cage have resting energy needs, determined from Figure 26-2. Although sepsis and burn injuries were found experimentally to increase energy expenditure 25% to 35% in dogs,101 more recent clinical studies found that the energy needs of resting critically ill, postoperative, and severely traumatized dogs were not higher than the basal needs of healthy animals.97 Based on these considerations and the complications associated with overfeeding, we determine initial estimates of energy needs on the basal requirement for the current body weight of the animal. Studies in humans suggest that metabolic rates greater than twice the basal requirement rarely occur, even in severely injured patients. In addition, overestimating nutrient needs increases the risk of the patient for problems associated with overfeeding.

The protein requirements of critically ill patients are not known. The protein requirements of young animals for growth are approximately 17% to 22% of total calories,87 and we use this guideline as an estimate for patients fed liquid-formula diets containing high-quality protein. Commercial pet foods may have lower protein quality and digestibility. If such diets are fed, higher protein concentrations (25% to 40% of calories) are required. We have used liquid diets containing 17% to 20% of kilocalories as protein in small animal patients with severe chronic renal failure successfully for short periods (<2 weeks), and have not found further restriction to be necessary. Patients with protein-losing diseases (e.g., protein-losing enteropathy or nephropathy) should have their estimated losses replaced. Protein losses by patients with protein-losing nephropathy are small relative to daily needs.19 In contrast, burned patients may lose significant amounts of protein, which may be replaced using diets containing higher percentages of kilocalories as protein.64

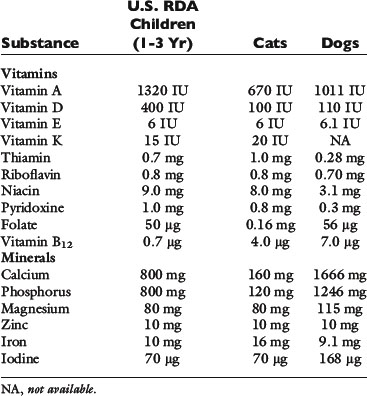

Hospitalized patients also require essential fatty acids, minerals, and vitamins. Specific vitamin and mineral needs depend on the type and severity of the underlying disease process. For short-term nutritional supplementation, at least sodium, chloride, potassium, phosphate, calcium, and magnesium should be provided. Provision of supplemental zinc should also be considered, especially in anorexic patients with gastrointestinal disease, where losses may be increased.102 Zinc also is important because of its role in protein synthesis, immune function, in vitro phagocytic activity, and taste and smell.82 Liquid enteral diets for nutritional support contain all the necessary minerals; so additional supplementation probably is not warranted. No studies have specifically evaluated the needs of veterinary patients for these nutrients. At present, provision of vitamins at or near the National Research Council requirements for growth seems reasonable in the absence of any specific contraindication77 (Table 26-2).

Appetite stimulation

The primary objective of nutritional support is to reestablish voluntary food intake. When enteral feeding techniques of nutritional support are necessary, they should only be used until the animal is eating adequate calories voluntarily. Food must be offered regularly to evaluate appetite. Food intake of hospitalized patients should be measured and calorie intake should be recorded daily to evaluate adequate nutrition. Electronic scales that weigh to the nearest gram are inexpensive, and allow the food and its container to be weighed in and out of the cage.

Dry, adult pet foods contain between 325 to 450 kcal per 8 oz and canned foods contain approximately 1 kcal/g. To estimate the adequacy of food intake, multiply the caloric density of the food by the amount eaten. If the result is less than two thirds of the goal intake, nutritional support by means of an enteral feeding tube may be necessary.

Nursing techniques to improve and encourage food intake are the simplest methods of nutritional support. If it is possible for owners to bring food from home and feed the patient out of its cage, this should be encouraged. Elizabethan collars should be removed under supervision when tempting an animal to eat. Petting and vocal reassurance when food is offered may induce some animals to begin eating again. Warming food to body temperature to enhance aroma or changing the type of food offered may help. If the animal’s nasal passages are occluded by exudates, cleaning them with warm water or saline may improve olfaction.

When introducing a new food to ill patients, care should be taken to minimize the possibility of creating a learned food aversion. A learned aversion is the association of an adverse stimulus with a novel diet, so that when the animal is offered the diet again it associates the food with feelings of ill health and refuses to eat it. If instituting a particular diet as part of long-term patient treatment, it should not be introduced during hospitalization if at all possible. Introducing the diet when the animal is feeling better, so that it associates a feeling of well-being with the new food, increases the probability of success.

Learned aversions in veterinary patients have not been studied in any systematic way, but they may occur. In fact, this may be one reason some veterinary therapeutic diets are difficult to institute in sick animals. A variety of chemicals have been used to stimulate appetite. Two commonly recommended pharmacologic agents are B vitamins and appetite-stimulating drugs. There is no evidence that administration of any of the individual B vitamins or combinations of them stimulates food intake in sick dogs or cats. Sick animals may have vitamin deficits, but they also have energy and other nutrient deficits that must be addressed simultaneously if nutritional support is to be effective.

Drugs used to stimulate appetite include the benzodiazepine derivatives, oxazepam (Serax, Wyeth, Madison, N.J.) and diazepam (Valium, Roche, Basel, Switzerland), the antiserotonergic agent, cyproheptadine (Periactin, Merck, Whitehouse Station, N.J.) and more recently the antidepressant agent, Mirtazapine (Remeron, Merck, Whitehouse Station, N.J.).66 However, it should be stressed that these drugs are only short-term options, and should not be used unless enteral nutrition support in the form of a temporary feeding tube is not an option. These medications should not be used for more than 24 to 48 hours in patients that are not consuming adequate nutrition.

Benzodiazepines are effective appetite stimulants in healthy dogs and cats.31 No controlled studies are available in veterinary patients for any of these compounds, which appear to be more effective for psychogenic than for pathologic anorexia. Psychogenic, or fear-induced, anorexia is common in hospitalized dogs and cats because of the strange surroundings, the stress of disease and trauma, and the unfamiliar human beings caring for them. Administration of 0.1 to 0.2 mg/kg body weight of diazepam intravenously, or 2.5 mg per cat per feeding of oxazepam orally, has been recommended to stimulate food intake in these settings.66 The recommended dosage of cyproheptadine for cats is 2 mg orally, two to three times daily. Although sometimes effective for psychogenic anorexia, these drugs do not appear to be effective for pathologic, disease-induced anorexia. Moreover, their sedative effects are undesirable in depressed animals, and they are contraindicated in patients with liver disease.95

Mirtazapine (Remeron) is a tricyclic antidepressant and an antiemetic in human medicine. It has been more recently used in canine oncology patients as an appetite stimulant at a dose of 15 to 30 mg by mouth once daily (cats can be dosed at 3.75 mg every 48 to 72 hours).58 In humans antidepressants are commonly tapered in consideration of antidepressant discontinuation syndrome, the significance of which has not been well characterized in pets, but its consideration may be advised.98

Other drugs, including prednisone (0.25 to 0.5 mg/kg body weight every other day) have been used to stimulate appetite.66 Although any of these drugs may be effective in isolated patients, none have been tested in controlled trials in veterinary medicine, and none have been demonstrated to be of consistent value. The greatest danger of pharmacologic appetite stimulation is that its use may give the false impression that adequate nutritional support is being provided. These drugs often stimulate animals to eat small meals immediately,66 and the clinician may conclude that food intake is adequate. Unless the total quantity of food eaten is measured, however, it cannot be determined if the animal continues to eat over the remainder of the 24-hour period. Use of these drugs should be restricted to animals in which food intake is being measured because of the inconsistent response to their use and the probability of delay of appropriate nutritional support.

Syringe feeding

Syringe feeding may provide some nutrition, but is not recommended due to the stress imposed on the patient and the increased risk of aspiration pneumonia, particularly in critically ill or mentally depressed patients. In addition, syringe feeding is time-consuming for the veterinary staff and the volume of food often negates the act of syringe feeding (e.g., a 10-lb cat would need to be force fed 24 to 10 mL syringes of food; a 60-lb dog needing approximately 1000 calories daily would need to be force fed 20 to 60 mL syringes of food). Lastly, the act of force-feeding a sick patient can result in the development of food aversions. If all attempts to induce the animal to eat voluntarily fail, an indwelling enteral feeding tube should be considered in place of syringe feeding.

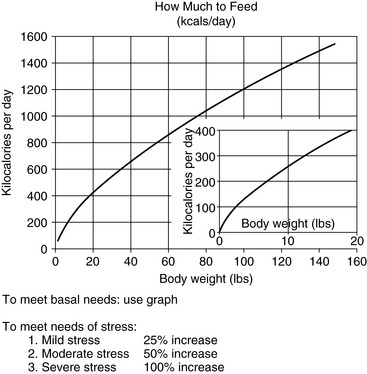

Orogastric feeding tubes for neonatal nutrition

Neonates may be fed by passing a tube through the mouth or nose into the stomach for each feeding (Figure 26-3). To pass an orogastric feeding tube,24,35,94 first measure the distance from the mouth to the tenth rib and mark the tube with permanent marker. Lubricate the end of the tube with a water-soluble lubricant. Pass the tube through the mouth and into the pharynx. Hold the animal’s head at the normal angle of articulation to minimize the possibility of endotracheal intubation. When the animal swallows, advance the tube into the esophagus to the depth of the premeasured mark. Using limited restraint and opening the mouth just far enough to introduce the tube minimizes the animal’s objection to the procedure. Information on neonatal caloric requirements, commercial milk replacers, and instructions for feeding puppies30 and kittens39 from birth to weaning are available in written literature.13

Nasoenteric feeding tubes

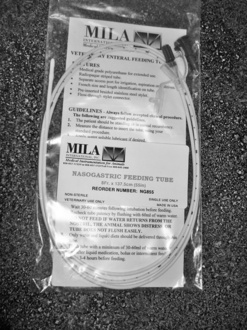

Nasoenteric (nasoesophageal or nasogastric) feeding tubes should be placed for short-term (3 to 5 days) nutritional support in any patient that has not consumed or is not expected to consume adequate nutrition within 3 days of hospitalization. Techniques of nasoenteric tube intubation are available in written1,14,26,27 and video literature;14 the materials needed for this procedure are listed in Box 26-1. Nasoenteric feeding tubes are made in varying sizes and lengths, from a variety of materials by different manufacturers (Box 26-2). Polyvinyl chloride tubes are inexpensive and work well for intragastric feeding. They may harden if left in for prolonged periods, however, and should be changed approximately every 3 to 4 weeks. Polyurethane or silicone tubes are more expensive, but are resistant to gastric acid and may be used for prolonged periods. We choose the least expensive tube needed in the largest diameter and longest length that the patient can tolerate comfortably. Large-diameter tubes present less resistance to solution flow, whereas long tubes can be placed into the stomach, secured to the head, and still be attached behind an Elizabethan collar for easy access.

Box 26-1 List of Materials Needed for Nasoenteric Tube Placement

2. Stylet or guidewire (optional for tubes placed in large dogs, recommend the PTFE wire 0.35 × 180 cm or the hydrophilic 0.35 × 260 cm straight guidewires from Merit medical)

3. Topical anesthetic (Lidocaine) to desensitize nostril (divide dose by 3 and give each dose 5 minutes apart before tube placement)

4. Sterile, water-soluble lubricating jelly (Surgilube, Savage Laboratories, Melville, N.Y.) or lidocaine jelly 2% (Akorn, Inc., Buffalo Grove, Ill.) to lubricate the feeding tube and lubricate the guidewire.

5. Permanent marker to mark and adhesive tape to secure feeding tube

9. Suture material (2-0 or 3-0 Ethilon) to secure feeding tube

Box 26-2 Manufacturers of Products for Enteral Nutritional Support

A: feeding tubes (a: nasojejunal feeding tubes)

C: guide wires, placement devices, or placement kits

Abbott Laboratories—Animal Health [A, B, C]*

http://www.abbottanimalhealth.com/

http://abbottnutrition.com/ (Ross Products)

Bard Access Systems, Inc. [A, C; low profile devices]

Kendall Healthcare Products (Now part of Covidien) [A, a, C, D]*

http://www.kendallhealthcare.com/

MILA International, Inc. [A, a; low profile devices]*

Merit Medical [C]*

Smiths Medical North America [A, B, C; gastrostomy tube introduction set]

* The authors preferred companies for enteral nutrition products.

Recommended tube sizes are listed in Box 26-1. A weasel-wire or guidewire/stylet (0.035 cm for 8 Fr or 10 Fr feeding tubes) can be used to assist passage of the tube (taking care that the wire/stylet does not stick out beyond the feeding tube). Sterile water soluble, lubricating jelly should be instilled into the feeding tube before introducing the stylet to facilitate easy removal of the stylet after the tube has been passed.

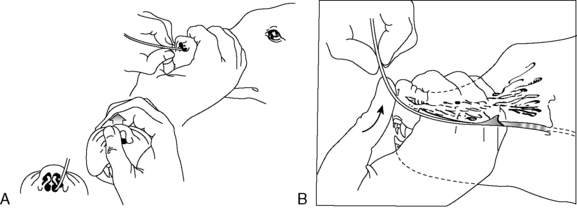

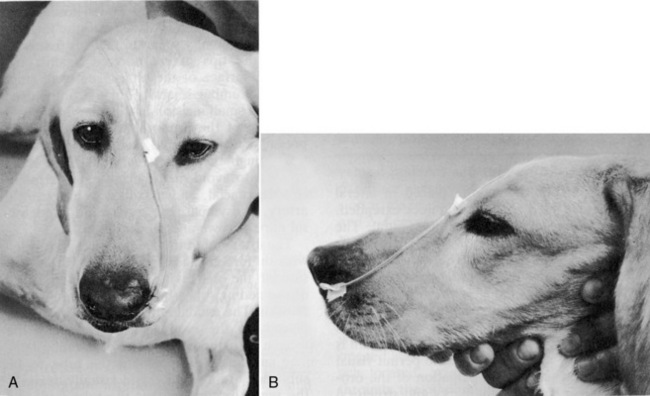

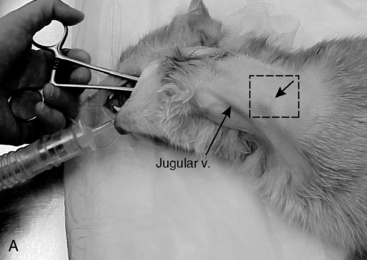

To pass a nasoenteric tube, a topical anesthetic is instilled into a nostril (4 to 5 drops of 0.5% proparacaine hydrochloride for cats or 2% lidocaine hydrochloride for dogs). The authors recommend repeating this step 2 to 3 times every 5 minutes before tube placement for adequate local analgesia. Most patients are depressed from their underlying disease and only require topical anesthetic. Based upon a recent prospective enteral nutrition study, 31 of 54 (57.5%) dogs required no sedation for feeding tube placement, 19 of 54 (35.1%) required mild sedation and 4 of 54 (7.4%) dogs had feeding tubes placed postoperatively while anesthetized.47 If sedation is required, a reversible opioid/benzodiazepine combination is recommended. Before passing the tube, measure the distance from the nostril to the stomach (approximately the caudal margin of the last rib at the level of the costochondral junction) and mark the tube with permanent marker. With the animal’s head held at the normal static angle of articulation to avoid tracheal intubation, the tube is passed through the nose of the patient by directing it caudomedially, then ventrally and caudally as the nasal planum is pressed upward (Figure 26-4). For doliocephalic dogs greater than 25 lb, pushing the tip of the nose upward in dogs, as the tube is passed, guides the tube into the ventral meatus.27 Slightly flexing the head downward may be helpful in directing the tube into the esophagus. For small dogs and cats, one should pass the tube directly through the ventral meatus without manipulating the nose. In other respects, the technique for cats is similar to that described for dogs.

Figure 26-4 Position of head during nasogastric intubations.

(From Abood SK, Buffington CA. Improved nasogastric intubation technique for administration of nutritional support in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1991;199:577–579.)

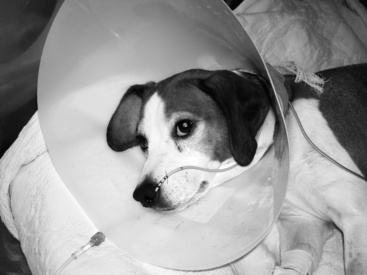

Once the tube is installed, the stylet (if present) is removed and the position of the tube in the stomach or esophagus is checked for negative suction/gastric fluid. Placement should always be confirmed with a lateral/dorsal ventral cervico-thoracic radiograph. Many commercial feeding tubes have radiopaque markings to confirm the tube’s position. Once in place, the tube is sutured with a pursue string and Chinese finger trap suture pattern (Ethilon or silk suture) (Figure 26-5) or fixed with cyanoacrylate adhesive (Superglue) just lateral to the nostril in the nasal fold to avoid curling of the tube (Figure 26-6). Several knots should be placed at the first suture site and then a Chinese finger trap method applied for three to four throws to prevent movement of the tube. A second suture should be placed and secured to the lateral cheek (Figure 26-7). An Elizabethan collar is placed on all animals to prevent inadvertent tube removal (Figure 26-8). Topical lidocaine can be administered if the patient experiences retractable sneezing postplacement. Although uncommon, mild epistaxis may be seen if the nasal turbinates are irritated during placement.

Figure 26-5 Technique for securing a nasoenteric tube with a purse-string and Chinese finger trap suture pattern. Tube should be secured as close to the nostril as possible.

Figure 26-6 Technique for securing a nasoenteric tube. Tube should be secured as close to the nostril as possible.

(From Abood SK, Mauterer JV, McLoughlin MA, Buffington CA. Nutritional support of hospitalized patients. In: Slatter DH, editor. Textbook of small animal surgery, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co, 1993.)

Figure 26-7 Canine patient with nasogastric enteral feeding tube in place sutured at both the nostril and cheek.

Figure 26-8 Dog with immune-mediated hemolytic anemia being feed through a nasoenteric feeding tube with an Elizabethan collar in place to protect the feeding tube.

Nasogastric tubes also may be used for perioperative gastric reflux to remove gastric fluids and decrease the risk of regurgitation and aspiration pneumonia postoperatively. NE tubes may also be temporarily placed for administration of activated charcoal in acute toxicities.22 To prevent occlusion with food or mucus, NE feeding tubes should be flushed with water before and after each feeding, and kept securely capped so that water remains in the tube between feedings.

Esophagostomy feeding tubes

Esophagostomy tubes are specifically indicated for patients requiring prolonged feedings with at-home care or bypass of the oral cavity or oropharynx due to dysphagia, infection, inflammation, neoplasia, fracture, oronasal fistula, surgical procedures, or trauma.85,96 The diameter and length of the esophagostomy tube depends upon the size of the patient, type of diet, and personal preference. Soft red rubber urethral catheters or Silastic tubing are used commonly as esophagostomy feeding tubes; recommended feeding tube sizes are 12 to 16 Fr catheters for cats and dogs under 10 kg, and 12 to 20 Fr catheters for larger dogs (Stallion urinary catheters 6.6 mm × 137 cm (J-90s; Jorgensen Laboratories). The larger diameter feeding tubes (>14 Fr) permit feeding of pureed commercial pet foods. The distal end of esophagostomy tubes should not be placed through the lower esophageal high-pressure zone into the stomach. Studies have shown that such placement can cause gastroesophageal reflux by disrupting the integrity of this caudal esophageal high-pressure zone.25,63 Esophageal dysfunction, including abnormal clearing of acid within the distal esophagus, also may occur.61 In addition, chronic esophageal irritation by refluxed gastric acid may result in esophageal stricture formation. Placing the distal end of the esophagostomy feeding tube in the anterior or midthoracic region of the esophagus prevents mechanical disruption of the caudal esophageal high-pressure zone. Secondary peristaltic waves move the food bolus through the remainder of the esophagus into the stomach.

The necessary materials required for this technique are listed in Box 26-3. To place the esophagostomy tube, the patient is anesthetized and intubated (with either a short-acting injectable or inhalant anesthetic technique) and placed in right lateral recumbency with the head and neck extended. The hair is clipped from the lateral and ventral aspects of the neck using the vertical ramus of the mandible, the base of the vertical ear canal, and the caudal edge of the larynx as landmarks. The skin is aseptically prepared for surgery. The mouth is held open by an oral speculum to permit visual examination of the oral cavity and digital palpation of the oropharynx for surgical landmarks and structural abnormalities.

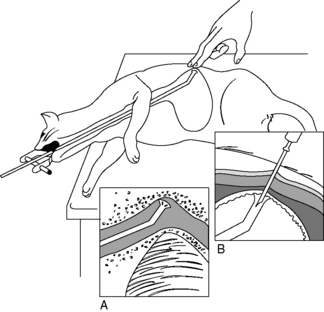

A long curved Carmalt or Mixter forcep is inserted through the oral cavity and oropharynx into the proximal one third of the esophagus (Figure 26-9, A). The instrument is pressed laterally against the esophageal wall to create a visible bulge in the skin along the left lateral aspect of the neck, dorsal to the jugular vein. A 1 to 2 cm incision is made through the skin and subcutaneous tissues directly over the end of the forceps (Figure 26-9, B). A number 15-scalpel blade can be used to make a small incision in the esophageal wall at the tip of the forceps, or gentle pressure can be applied to them to force the tips through the esophageal wall. Care must taken to avoid the external jugular, linguofacial and maxillary veins, carotid artery, vagosympathetic trunk, and hypoglossal nerve. The distal end of the feeding tube is grasped with the forceps and drawn through the incision into the oral cavity (Figure 26-9, C). Only a small portion of the feeding tube should remain exterior to the skin, this will facilitate ease of rotating/flipping the tube (Figure 26-9, D). The distal end of the feeding tube is gently manipulated into the esophagus by retracting the tongue and extending the end of the tube 180° (Figure 26-9, E). The surgeon should palpate the tube to be sure there are no kinks, and visually examine the region to confirm that the tube is placed caudal to the pharyngeal region. A lateral and ventral-dorsal cervico-thoracic radiograph should be taken to document correct placement. Once in place, the tube is sutured (Ethilon or PDS suture) at the skin with a purse string around the tube and then a Chinese finger trap method applied for three to four throws to prevent movement of the tube. A light bandage should be applied over the tube and the tube should be evaluated by a veterinarian for infection or movement and rebandaged daily.

Esophagostomy tubes can be maintained for several weeks or months with good nursing care. A small amount of drainage may occur at the incision site; the area should be cleaned and bandaged daily or every other day as needed. Complications associated with esophagostomy feeding tubes may include local infection and swelling or cellulitis, coughing, and gastroesophageal reflux if the tube is improperly placed; vomiting and aspiration of food if the animal is fed too much food rapidly; esophageal erosion or esophagitis if the tube is too large or left in place too long; and premature displacement or occlusion of the tube if not cared for adequately.49,63 When tube feeding is no longer necessary, esophagostomy tubes can be removed without sedation and discomfort. The cervical wound is left to heal by second intention.

Esophagostomy feeding tubes offer several advantages over other enterally-placed feeding tubes: they require only a single surgical incision to place; they do not require specialized or costly equipment such as an endoscope; they do not require sedation or anesthesia for tube removal; patients tolerate these tubes well; tubes can be left in place for extended periods of time, and these feeding tubes are easy for clients to manage in the home environment.

Surgical gastrostomy or jejunostomy tube via gastrostomy tube

When nutrients cannot be introduced proximal to the stomach in patients with normal gastrointestinal function, gastrostomy tube feeding is an excellent method of temporary or permanent nutritional support.25,26 Gastrostomy feeding tubes are specifically indicated in patients that are comatose or in those that require bypass of the oral, oral pharynx, larynx, and esophagus due to neurologic or neuromuscular diseases, dysphagia, regurgitation, neoplasia, obstruction, inflammation, stricture, or following surgical procedures of the head and neck.

Gastrostomy feeding tubes generally are placed through a limited left paracostal laparotomy, which provides excellent exposure to the gastric fundus. They can be placed in conjunction with other abdominal procedures through a ventral midline celiotomy. If an endoscope is available, it may be used to place the gastrostomy tube percutaneously. The patient is anesthetized with a general inhalant anesthetic and placed in right lateral recumbency. Endotracheal intubation is recommended to ensure a patent airway and to prevent aspiration of gastric contents during manipulation of the stomach. The hair is clipped in the left paracostal region from dorsal to ventral midline, and the skin aseptically prepared for surgery. A 4 to 8 cm curvilinear incision is made in the skin caudal to the last rib and 2 to 4 cm ventral to the paravertebral epaxial muscles.49

Care must be taken to ensure that this incision is located ventral enough to enter the peritoneal cavity. The external and internal abdominal oblique and transversus muscles can be separated by blunt dissection or incised with a scalpel blade. The peritoneal cavity is opened and the greater curvature of the stomach identified. A small stab incision is made through the abdominal wall, cranial to the celiotomy incision and directly caudal to the last rib or between the last two ribs. The tip of a large-bore, mushroom-tipped Pezzer catheter (14 to 28 Fr) is passed through this incision into the abdominal cavity. Two stay sutures are placed in the gastric fundus and used to retract the stomach into the celiotomy incision. A relatively avascular area near the greater curvature of the fundic region of the stomach should be chosen, and moistened laparotomy sponges used to isolate this region of the stomach for feeding tube placement. Two full- thickness purse-string sutures are placed concentrically through all layers of the gastric wall using a 3-0 synthetic absorbable monofilament suture material. The free ends of the sutures are tagged with forceps. A No. 11 scalpel blade is used to make a small stab incision in the center of the inner purse-string suture. Care must be taken to prevent leakage of gastric contents from this stab incision. The mushroom tip of the catheter is inserted into the gastric lumen, the inner purse-string suture is gently tightened around the tube and tied, after which the second suture is tightened to minimize leakage around the tube. Jejunostomy or enterostomy feeding tubes may be advanced through a gastrostomy tube during open abdominal surgery to provide postpyloric feeding without an increased risk of surgical dehiscence at the site. Percutaneous radiologic gastrojejunostomy (PRGJ) tubes have recently been described.8 However, at this time their use is limited to specialty hospitals with fluoroscopic equipment. Specific indications for use of the enterostomy or jejunostomy feeding tubes may include pancreatitis, pancreatic surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, proximal GI obstruction, neoplasia, or extensive gastrointestinal surgery.

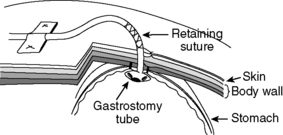

The gastrostomy site is secured to the left abdominal wall with approximately 4 to 6 synthetic absorbable monofilament sutures placed in a mattress pattern through the seromuscular layer of the stomach and the transverses abdominis muscle of the body wall. The gastropexy suture should be placed as close as possible to the feeding tube. The paracostal incision then is closed in a routine manner. The feeding tube should be capped and fixed to the skin using 3-0 nylon sutures through an adhesive tape butterfly or a 0 nylon antitension suture (Figure 26-10). The tube then is incorporated into a light abdominal bandage to prevent removal by the patient.

Figure 26-10 Technique for securing gastrostomy tube. Retaining suture and/or adhesive tape can be used.

(Line drawing by Dana Schumacher.)

Gastrostomy feeding tubes can be maintained in patients for months with good nursing care. Tubes should remain in place for a minimum of 5 to 7 days, and preferably 14 days, to allow firm adhesions (or a stoma) to form between the stomach and peritoneum. Formation of the stoma tract prevents leakage of food or fluid into the peritoneal cavity. If prolonged feeding tube use is indicated, the original mushroom tipped catheter can be removed and replaced by a low profile tube to improve patient comfort.92 When the gastrostomy feeding tube is no longer needed, it may be removed with gentle but firm traction and the wound left to heal by second intention.

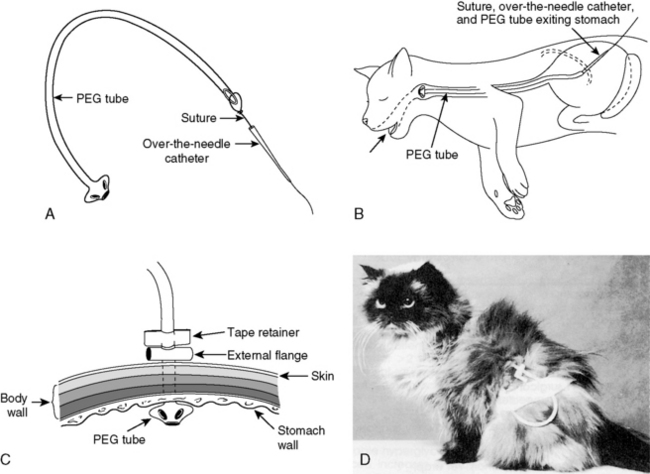

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG)

The patient is anesthetized (with a neuroleptanalgesic or general inhalant anesthetic) and placed in right lateral recumbency. The left paracostal region is clipped and the skin aseptically prepared for surgery. An oral speculum is placed in the patient’s mouth and a flexible endoscope, with a biopsy channel, is passed through the mouth and esophagus into the stomach. The stomach is insufflated with air until distention of the left abdominal wall is visible externally. This procedure displaces any abdominal viscera that were located between the stomach and left body wall. The endoscope then is positioned so the illuminated end is located within the stomach directly caudal to the last rib.

A small stab incision is made through the skin at this site. An 18-gauge intravenous cannula with a needle stylet is placed through the skin incision and through the abdominal and gastric walls into the gastric lumen. The endoscope is repositioned within the stomach to visualize and confirm the presence of the cannula. The stylet is removed from the cannula and the end of a 1-0 or 2-0 piece of suture material is passed through the cannula into the gastric lumen. The length of suture material required can be estimated by measuring from the tip of the animal’s nose to the greater trochanter of the femur. The biopsy snare is passed through the biopsy channel of the endoscope and used to grasp the suture material. The biopsy instrument with the suture attached should not be retracted through the biopsy channel of the endoscope. While holding the biopsy snare in a closed position to retain the suture material, the entire endoscope is withdrawn from the stomach through the mouth. The cannula can then be removed from the abdominal wall, being careful not to remove the suture. The suture end exiting from the mouth is passed retrograde through this cannula. An 18-gauge needle is passed through the feeding tube just below the bevel of the catheter, and the suture is passed through the needle and tied securely to the tube (Figure 26-11, A).

Figure 26-11 Technique for passing a percutaneous endoscopically guided gastrostomy tube. A, An 18-gauge needle is passed through the feeding tube just below the bevel of the catheter, and the suture is passed through the needle and tied securely to the tube. B, The cannula and feeding tube pass through the mouth, esophagus, and stomach, and exit through the gastric and abdominal walls. C, An external flange can be placed around the feeding tube to prevent separation of the stomach from the abdominal wall. D, A lightweight bandage or stockinette can be used to protect the tube exit site.

(Line drawings by Dana Schumacher.)

The gastrostomy tube is stretched and gently manipulated to feed the tapered end into the flared end of the cannula, which guides the feeding tube back through the gastric and abdominal walls. The cannula and feeding tube pass through the mouth, oropharynx, esophagus, and stomach, and exit through the gastric and abdominal walls (Figure 26-11, B). The cannula is removed, and the gastrostomy tube is gently retracted to pull the internal flange and mushroom tip securely against the gastric mucosa. Replacement of the endoscope into the stomach allows visualization of the positioning of the tube. An external flange can be placed around the feeding tube next to the skin to prevent separation of the stomach from the abdominal wall, until a permanent adhesion forms (Figure 26-11, C). The remaining end of the tube is capped and fixed to the skin with an antitension suture. A lightweight abdominal bandage or stockinette can be used to protect the exit site from contamination (Figure 26-11, D). Complications associated with gastrostomy tubes include leakage around the feeding tube resulting in peritonitis, necrotizing fasciitis, or subcutaneous abscessation.11,14,25 This does not, however, mean that tubes should be secured very tightly, which can cause the same problems secondary to ischemia. Vomiting, regurgitation, gastroesophageal reflux, and aspiration pneumonia may also occur, usually as a consequence of overdistention of the stomach during feeding.

Percutaneous nonendoscopic gastrostomy

Methods of blind placement (nonsurgical or nonendoscopic) of gastrostomy tubes in dogs and cats have been reported.36,68 The technique is similar to that described above for endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement, except that a gastrostomy tube introduction set (see Box 26-2) is used instead of an endoscope to guide the suture from the skin, through the stomach and esophagus, to the oral cavity (Figure 26-12). Alternative techniques for gastric feeding tube placement were developed for practitioners with limited access to an endoscope and for patients in which abdominal exploration or endoscopy are not indicated as part of case management, yet controlled, postesophageal nutrition support is indicated. The blind placement of a gastrostomy feeding tube is not indicated in patients with esophageal stricture or other obstruction, primary gastric disease, or gastric outflow obstruction.

Figure 26-12 Percutaneous nonendoscopic gastrostomy tube placement. Passage of the placement device with animal in right lateral recumbency. Palpation of the device in the stomach is facilitated by positioning the animal’s head over the end of the table and extended: A, Tube placement device rotated 90 degrees counterclockwise to pass freely over the base of the heart. B, The catheter needle is inserted through the skin into the flared end of the device at a 45-degree angle parallel with the distal end of the device.

(Drawing by Tim Vojt).

Animals may be fed through esophagostomy or gastrostomy tubes soon after they recover from anesthesia. Although the stomach of normal animals serves as a feeding reservoir, prolonged anorexia may decrease gastric capacity or cause gastric atony. Initial feeding volumes of 5 to 10 mL/kg of body weight per feeding (four feedings per day) usually are safe and are increased as tolerance permits. Motility modifiers, such as metoclopramide (1 to 2 mg/kg/day added to intravenous fluids; 0.2 to 0.5 mg/kg orally or subcutaneously, three times a day) may stimulate gastric emptying if atony is present, but the effect is inconsistent. To prevent occlusion with food or mucus, feeding tubes are flushed with water before and after each feeding, and kept securely capped so that water remains in the tube between feedings. The materials required for placement of a PEG tube are listed in Box 26-4.

Box 26-4 List of Materials Needed for Percutaneous Gastrostomy Tube Placement

1. Endoscope or gastrostomy tube introduction set

3. Bard urologic catheter or polyurethane PEG with collapsible bumper

4. 14- to 22-gauge peripheral or indwelling catheter, or open end tom-cat catheter

6. Braunamid suture (Vetafil) 2-0; approximately 2 ft

8. 18- to 20-gauge, 1-inch needles

9. Rubber tubing (1.5 inch long) for external flange

10. 1-inch wide adhesive tape; approximately 6 inches long

13. Bandage material optional; Vet wrap, stockinette, cast padding, or Kling

Nasojejunal feeding tubes

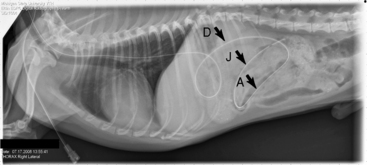

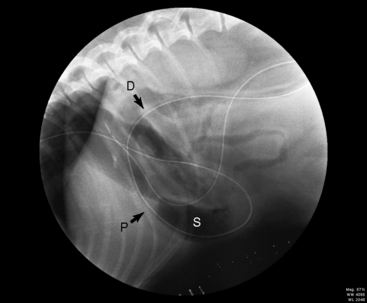

Placement of a feeding tube directly into a segment of the proximal small intestine, such as the descending duodenum or proximal jejunum, using fluoroscopic or endoscopic guidance has been advocated in small animal patients that cannot be fed more proximally.28,32,79 Specific indications for postpyloric feeding tubes may include pancreatitis, pancreatic surgery, hepatobiliary surgery, proximal GI obstruction, neoplasia or extensive gastrointestinal surgery, and a decreased level of consciousness. The placement of a NJ tube (Figure 26-13) involves a minimally invasive technique that can be done under intravenous sedation or a short anesthetic period (Figures 26-14 and 26-15). Techniques of nasojejunal tube intubation in dogs have recently been described.6,7,80,100 With experience these tubes can be placed in less than 15 minutes. The weighted tip is coated with lidocaine gel as a local anesthetic. A suture is placed around the feeding tube with a purse-string and Chinese finger trap pattern using a 2-0 to 3-0 synthetic or silk suture material. Nasojejunal feeding tubes should be secured with nonabsorbable suture at the nostril and side of the cheek. NJ feeding tubes are best suited for short-term (<1 week) delivery of postpyloric enteral nutritional in hospitalized patients. Administration of nutrients to the jejunum has minimal effect on pancreatic secretion and feedings can be continued despite vomiting.81,84 Indwelling NJ tubes can cause rhinitis, esophagitis, reflux, and dacryocystitis several days after placement but no more than is expected for nasoenteric tubes. Other concerns include retrograde movement of the tube into the stomach or esophagus. Retrograde movement can occur spontaneously or be associated with vomiting, but is least likely to occur when the tube is advanced far into the proximal jejunum. In one study evaluating fluoroscopic NJ placement in dogs, 17 of 20 tubes that were advanced into the jejunum remained in place until intentional removal. Reported complications included bile leakage from the externalized opening of the tube, retrograde movement of the tube if the tube was placed proximal to the caudal duodenal flexure, sneezing, and nasal discharge.100 When the tube is no longer necessary, it is removed without sedation by gentle traction.

Figure 26-14 Right lateral thoraco-abdominal radiograph of a recumbent dog showing the correct positioning of the nasojejunal tube with the distal tip in the jejunum just before removal (5 days after placement). D, descending duodenum; A, ascending duodenum; J, jejunum.

Figure 26-15 Fluoroscopic image of a recumbent dog showing the correct placement of the nasojejunal tube with the distal tip in the jejunum. D, duodenum; P, pylorus; S, body of the stomach.

Patients should be fed through the gastrointestinal tract whenever possible; however, some patients are not candidates for enteral nutritional support. Animals that are vomiting or regurgitating, who cannot be controlled with pharmacologic agents; those with adynamic ileus of the small intestine, intestinal obstruction, or severe mucosal disease; and those that cannot guard their respiratory tract should be fed parenterally (see Chapter 25).

Diets

Enteral diets for nutritional support should be palatable, easily digested, readily assimilated, efficiently used with a minimum of metabolic waste products, and easy to deliver. Box 26-5 presents criteria for selection of an appropriate diet.89 The ideal oral food for anorexic animals should be so well tolerated by the gastrointestinal mucosa that it can be administered to patients with gastritis, enteritis, or colitis without producing additional irritation. The choice of an appropriate diet for a given patient depends on the route chosen and any disease-related nutrient modifications. Injured or diseased animals should not lose weight while being fed the diet at the recommended dosage. Patients with orogastric or gastrostomy tubes can be fed by measured amounts of an appropriate canned food pureed with water in a blender to the desired consistency.

Box 26-5 Criteria for Selection of Liquid Enteral Diets

A. Categories of enteral diets

E. Specific Amino Acids for Cats

F. Electrolytes—sodium, potassium, and chloride at about 40 mEq/L have been adequate; should be adjusted based on laboratory determinations

G. Minerals and Vitamins—follow NRC recommendations in absence of specific information to the contrary

H. Osmolality—hypoalbuminemia: 250-650 mOsm/kg, depending on severity

Numerous commercial products are available for enteral support, most falling into one of two groups. The first group includes polymeric diets for use in patients with nearly normal gastrointestinal function. These products contain casein, soy, or egg albumin as protein; medium- or long-chain triglycerides as fat; glucose polymers as carbohydrates; and vitamins and minerals. Nutrients are provided in high-molecular-weight forms to maintain osmolality at approximately 350 mOsm/kg. These products also are low in lactose and residue.

Defined-formula diets, the other major group, are those modified to accommodate disease-associated limitations on nutrient intake. Peptide and “elemental” diets essentially are predigested forms of the polymeric diets, which are recommended for use with enterotomy or jejunostomy tubes (nasojejunal or J through G tubes). However, a recent study evaluated the short-term use of polymeric diets (such as Clinicare) (Figure 26-16) and found no difference in outcome or incidence of diarrhea when compared with Peptamin.10 In defined-formula diets, the protein is present in the form of peptides or amino acids, and carbohydrates as oligosaccharides or monosaccharides. These usually are low in fat, and many have a portion of the fat present as medium-chain triglyceride oil to enhance absorption. The osmolality of these solutions may be higher (450 to 850 mOsm/L) than meal replacement formulas because of the inclusion of small-molecular-weight nutrients. These diets have been recommended for patients with abnormal gastrointestinal function (e.g., severe inflammatory bowel disease or pancreatic insufficiency).57 Other defined diets have been marketed for impaired hepatic, renal, and respiratory function, and for stress. The efficacy of these formulas has not yet been completely established.89,91

A third class of enteral product is the feeding module. These products are concentrated sources of one nutrient (i.e., protein, fat, or carbohydrate). Modules may be added to increase specific nutrient concentrations or to reduce the required volumes. They also may increase the osmolality of the formulation. In the past, when using a human enteral product, we supplemented diets containing 17% of the kilocalories as protein, with 5 g protein powder (ProMod) per 8 oz diet for all cats with normal protein needs, and for dogs with increased protein needs. Commercial nutritional products for humans are available at large public and hospital pharmacies, or manufacturers may be contacted for local availability. A local nutrition support service dietitian may also be of help; these professionals may have nutritional products and delivery apparatus available, and possess extensive training and experience in nutritional support. Blenderized gruels made with commercial canned dog or cat diets are suitable for use in feeding tubes larger than 14 Fr in size. Specific products marketed for critically ill dogs or cats have been recently published.86Table 26-3 presents the nutrient compositions of the liquid enteral products currently used in the Critical Care Unit at Michigan State University and in the Small Animal Intensive Care Unit at The Ohio State University. None of the human enteral products appear to contain adequate arginine for cats. Signs compatible with arginine deficiency have been reported after prolonged feeding of enteral diets designed for humans and those designed specifically for cats. In the absence of data to support other recommendations, we add 1 mg arginine/kcal (approximately 200 to 300 mg/cat/day) to human enteral liquid diets fed to cats. Arginine (as the hydrochloride salt) is inexpensive and readily available at health food stores and at many pharmacies.

Table 26-3 Nutrient Composition of Veterinary Liquid Enteral Products

| Product | CliniCare Canine/Feline | CliniCare Feline Renal |

|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Abbott Labs | Abbott Labs |

| Kcal/8 oz can (g) | 237 (1) | 237 (1) |

| mOsm/kg | 340 | 290 |

| Kcal/mL | 1 | 1 |

| Protein (g) | 8.2 g/100 kcal | 6.3 g/100 kcal |

| Protein source | Casein, whey protein | Casein, whey protein |

| Fat (g) | 5.1 g/100 kcal | 6.7 g per 100 kcal |

| Fat source | Soybean oil, chicken fat | Soybean oil, chicken fat |

| Carbohydrate (g) | 6.8 g/100 kcal | 6.3 g/100 kcal |

| Carbohydrate source | Corn maltodextrin | Corn maltodextrin |

| Fiber | 0.1 g/100 kcal | 0.1 g/100 kcal |

| Na+ % Dry Matter | 0.35 | 0.27 |

| Na+ (mg) | 80 mg/100 kcal | 62 mg/100 kcal |

| K+ % dry matter | 0.70 | 0.55 |

| K+ (mg) | 160 mg/100 kcal | 125 mg/100 kcal |

| Ca2+ % dry matter | 0.61 | 0.55 |

| Ca2+ (mg) | 140 mg/100 kcal | 125 mg/100 kcal |

| Pi (mg) | 120 mg/100 kcal | 104 mg/100 kcal |

| Mg2+ (mg) | 10 mg/100 kcal | 9 mg/100 kcal |

Rate and volume of feeding

Approach the calculated goal for nutrients and fluids over approximately 24 to 72 hours to prevent vomiting, abdominal distention or signs of colic, and diarrhea (Box 26-6). Slow rates of administration, particularly in animals that have been inappetent for prolonged periods, prevent the problems of diarrhea and cramping, and maximize the uptake of nutrients.

Enteral nutrition delivery methods

The two most common EN delivery methods for veterinary and human patients are continuous infusion or intermittent bolus feedings. Critically ill patients with impaired gastrointestinal mobility may better tolerate continuous infusion of nutrition, whereas intermittent bolus feeding resembles a more physiologic method of providing calories. Randomized, controlled trials in human patients have failed to determine which delivery method is superior in providing prescribed calories with minimal complications.* Few studies have examined EN delivery systems in critically ill small animals. A pilot study evaluating continuous infusion and intermittent bolus feeding was performed in 10 healthy dogs with gastrostomy tubes. No difference was found in weight maintenance, gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase, nitrogen balance, or feed digestibility.20 More recently, a retrospective study was performed at Michigan State University evaluating the percentage of prescribed nutrition delivered (PPND) in 37 dogs and 54 cats that were supported using nasoenteric feeding tubes.16 The PPND was not significantly different between patients fed continuously (99.0%) and patients fed intermittently (92.9%). This study also found that the frequencies of GI complications were not significantly different between the two delivery methods. Enterally fed dogs had a significantly higher frequency of regurgitation and diarrhea than enterally fed cats. The retrospective nature of this study precluded the authors from making conclusions regarding the cause for discrepancy between prescribed and delivered nutrition.

Limitations associated with interpreting data from retrospective research led Holahan and Abood to develop a prospective randomized clinical evaluation of continuous and intermittent feeding in critically ill dogs.47 Fifty-four dogs admitted to the critical care unit and requiring nutritional support with a nasoenteric (NE) feeding tube were enrolled. Dogs were randomized to receive either continuous infusion (Group C) or intermittent bolus (Group I) of liquid EN. The percentage of prescribed nutrition delivered (PPND) was calculated every 24 hours. The frequency of gastrointestinal (GI), mechanical, and technical complications was recorded and gastric residual volumes (GRVs) were measured. The median days of delivered nutrition support was 3 (range 1 to 8 days). PPND was significantly lower in Group C (98.4%) than Group I (100%). Although there was a statistically significant difference in the PPND between continuously and intermittently fed dogs, this difference was unlikely to be of clinical significance. Likewise, there was no statistically significant difference in GI or mechanical complications, whereas Group C had a significantly higher rate of technical complications (see later discussion). GRVs did not differ significantly between Group C (3.1 mL/kg) and Group I (6.3 mL/kg) and were not correlated to the incidence of vomiting or regurgitation. Critically ill dogs can be successfully supported with either continuous rate infusion (CRI) or intermittent bolus feeding of EN with few complications. Elevated GRVs may not warrant termination of enteral feeding.

This study was the first published prospective clinical trial comparing delivery methods in dogs with NE-tubes; it was also the first to evaluate gastric residual volumes (GRVs) in critically ill dogs. Subjects in both groups had GRVs measured and recorded every 4 hours. Median GRVs for all dogs were 4.5 mL/kg and no significant difference was identified between the two delivery methods. Additionally, no correlation was identified between the incidences of vomiting or regurgitation and the amount of GRVs. Results from this study have been used to establish guidelines and long-term goals in our Critical Care Unit focusing on minimizing complications and reducing technician time, while maximizing delivery of prescribed calories.

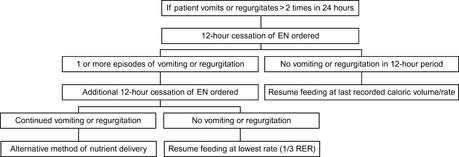

Bolus and CRI feeding instructions are outlined in Box 26-7 and a rescue protocol is described in Figure 26-17. Reservoirs and delivery tubes for feeding solutions are available from a number of manufacturers. Reservoirs containing a 12- to 24-hour supply of diet solution can be hung and allowed to drip in by gravity. Intermittent bolus feeding requires more veterinary staff time due to the set-up and contact needed every 4 to 6 hours for multiple feedings. Therefore we recommend continuous feeding (constant rate infusion) using a commercial available syringe pump. Holahan and Abood have found the Kangaroo 924 Enteral Feeding Pump (Figure 26-18) or Medfusion 2010i syringe pump (Figure 26-19) to be suitable for either bolus or CRI feedings. This allows delivery of a precise volume over a given time frame, minimizing the possibility of “overdosing” a patient with an excess volume or giving boluses too rapidly.

Box 26-7 Intermittent Bolus Feeding Instructions (to be done at each feeding)

1. Auscultate abdomen for gut sounds. Aspirate gently on tube; measure and record any gastric residual fluids, then replace fluid through tube. If more than half the volume previously fed is removed and the patient is showing signs of gastrointestinal intolerance (vomiting/regurgitation), do not feed animal at this time (wait until next scheduled feeding).

2. Inject 5-10 mL water through tube; if this produces coughing, the tube may be in the respiratory tract.

3. When satisfied the animal can be fed, resume feeding schedule. If necessary, place animal in sternal or right lateral recumbency. Solution should be warm to room temperature and should be fed slowly. Bolus feed over 30-60 minutes to assess the patient’s tolerance and monitor for vomiting or aspiration.

If The Animal Vomits, Stop Feeding

4. After feeding, flush the tube with 5-10 mL warm water and replace cap or cover, leaving the tube full of water.

5. Observe the animal for discomfort, colic, or diarrhea for the next few minutes.

6. Record each feeding and document any problems.

7. Nothing is to be administered via the tube, except the feeding solution, without the permission of the clinician.

Figure 26-17 Suggested Rescue Protocol for canine patients admitted to the critical care unit receiving enteral nutrition support through nasoenteric feeding tubes.47

Figure 26-19 Medfusion 2010i syringe pump for continuous or intermittent enteral feeding of cats and small dogs.

If the animal has been anorexic for more than 72 hours, the volume administered over the first 12 to 24 hours may be reduced by one third or one half of the total RER to reduce the risk of gastrointestinal intolerance. In most instances, feedings can be increased to the total calculated dose over 24 to 72 hours, unless anorexia has been prolonged. Most anorexic patients begin voluntary food consumption after the second or third day. If fluid losses are present, they can be replaced by administration of additional water along with the diet.

Gastric residual volumes (GRVs)

For human patients with feeding tubes that reside within the stomach, gastric residual volumes (GRVs) are checked every 4 to 6 hours, regardless of the method of feeding (bolus or continuous).65,73 The nasoenteric feeding tube should be aspirated and the GRV should be recorded. New evidence in veterinary medicine indicates that GRVs can be slowly administered back through the nasogastric tube over 5 minutes and flushed with 5 mL of water before the next scheduled feeding with no overt gastrointestinal complications observed.47 In many human hospitals, intolerance to enteral feeding is assessed in part by serially measuring gastric residual volumes (GRVs).71,72 High GRVs have been reported as a reason to stop feeding human patients. Gastric aspirates greater than 150 to 250 mL in a 4-hour period were considered a mark of intolerance in adults, and cessation of EN had been recommended to minimize risk of aspiration pneumonia.65 In a study of low birth weight infants, delayed gastric emptying was defined as GRVs greater than 5 mL/kg in any 4-hour period.48 However, routine suspension of EN due to large GRVs has been questioned in human medicine, as there is no consistent relationship demonstrated between aspiration and gastric residual volumes.53,69,73,74,93 The incidence of fourth hourly GRV was not different between the continuous and intermittent feeding groups,48 which is similar to the recent findings of Holahan et al. It has been previously thought in veterinary and human medicine that high GRVs correlated with a higher incidence of vomiting, regurgitation, and the incidence of aspiration pneumonia. However, no significant correlation between average GRVs (mL/kg) and occurrence of vomiting or regurgitation was found in the Holahan study, and only two patients on EN had aspiration pneumonia, both of which had radiographic evidence of pneumonia documented before the start of EN. There is a lack of evidence in veterinary medicine to suggest what an acceptable GRV might be, or whether this measurement is a reliable means of assessment of gastric intolerance. The authors conclude that termination of enteral feedings due to elevated GRVs in critically ill dogs may not be warranted, particularly in patients not exhibiting signs of vomiting or regurgitation.

Complications of enteral feeding

Mechanical, gastrointestinal, technical, and metabolic complications can occur with enteral tube feeding. Mechanical problems relate to placement (inadvertent placement of the tube into the trachea, regurgitation or vomiting up the tube, or removal of the tube by the patient) and maintenance of the tube, including clogged or blocked tubes. Tubes can become clogged if pills are crushed and forced into the tube, or if food is not adequately flushed out of the tube after bolus feeding or the tube is not capped to leave a column of water in the tube. Flushing clogged tubes with a variety of solutions (cranberry juice and cola beverages have been recommended in the past) may be irrational if the pK of the clogging material is not considered.12 Another potential problem that should be considered is drug incompatibility with enteral feeding formulas. Potassium chloride elixir is the most commonly reported incompatibility, causing formula precipitation and blocked tubes.4 Tube clogging is best prevented by prohibiting its use for the administration of nonliquid materials and by properly flushing and capping the tube after each use. To decrease the incidence of tube occlusion, we recommend flushing the tube with a small amount (3 to 5 mL) of warm water every 4 to 6 hours regardless of the delivery method; this becomes especially important in small dogs and cats.

Most of the gastrointestinal problems caused by enteral feeding result from too rapid administration of the solution, or feeding solutions of high osmolality (>600 mOsm). Solutions entering the duodenum too quickly can cause vomiting, cramps, and diarrhea by overwhelming the normal neural and endocrine control mechanisms of the gastrointestinal tract.18 Hyperosmolar solutions cause rapid fluid and electrolyte influx into the gut lumen, leading to abdominal distention and cramping. These problems can be managed by reducing the feeding rate or solution concentration, or by feeding diets that delay gastric emptying. Fiber-enriched human enteral products are marketed to normalize GI transit times, but there is little evidence to suggest that these products minimize or reduce diarrhea in tube-fed patients.91

Cold feeding solutions are thought to be a major cause of diarrhea, but research available to support this opinion is inconclusive. We have not observed problems with diets fed at room temperature and recommend that diets stored in a refrigerator be brought to room temperature before being tube fed or offered for oral consumption. Bacterial contamination of formulas during reconstitution and administration can also cause diarrhea,9 so diets should be handled carefully and not allowed to remain in the feeding tube system for more than 24 hours.40

Patient problems that may result in gastrointestinal intolerance to feeding include protein malnutrition, hypoalbuminemia from any cause, fat malabsorption, and associated gastrointestinal disorders. Hypoalbuminemia can lead to malabsorption and diarrhea because intravascular osmotic pressure required for nutrient uptake is greatly reduced.38 Pancreatic disease, biliary obstruction, ileitis, bacterial overgrowth, gastric surgery, and intestinal resection all can lead to varying degrees of fat malabsorption. Many medical disorders are associated with diarrhea,50 including enteric infections, malabsorption syndromes, gastroenteritis, mucosal defects, diabetes mellitus, carcinoid syndromes, hyperthyroidism, and immunodeficiency states.

The most important cause of diarrhea in tube-fed human patients is concomitant antibiotic or drug use because it is the most difficult factor to change. Development of diarrhea often results in discontinuation of tube feedings in an attempt to reduce the diarrhea that nursing staff and clinicians associate with liquid feedings. However, the problem may be the antibiotic used or related to the underlying disease process. By altering the normal gastrointestinal flora, antibiotic usage can also change the fatty acid composition of gut contents, which may adversely affect sodium and water absorption by the colon. Intestinal bacteria also may ferment undigested nutrients, forming organic acids, hydrogen and carbon dioxide gas, and ultimately causing diarrhea.

Many antibiotics and drugs have been associated with diarrhea including penicillins, aminoglycosides, cephalosporins, chloramphenicol, clindamycin, aminophylline, cimetidine, potassium chloride, digoxin, and magnesium-containing antacids.44 The oral suspensions of some antibiotics, electrolytes, and other medications are hyperosmolar, suggesting that these drugs may play a role in the pathogenesis of diarrhea.78 A study investigating the cause of diarrhea in tube-fed patients found that medicinal elixirs containing theophylline, as well as liquid preparations of acetaminophen, codeine, cimetidine, isoniazid, and vitamins all contained sorbitol. Although commonly added to improve the palatability of some medications, sorbitol is also known to have an osmotic effect in sensitive individuals and should be considered a potential cause of diarrhea in patients receiving enteral diets.33

Technical complications include: feeding stopped for diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, feeding stopped for owner visitation, feeding stopped for extended walks outside, equipment malfunction, syringe pump off, syringe pump disconnected, or accidental rate change. Care should be taken when patients are receiving enteral nutrition to minimize the time lost due to temporary discontinuation of enteral feedings. Mechanical complications were evaluated at Michigan State University. Dogs fed continuously lost a median of 0.5 hours of enteral nutrition, where dogs fed intermittently had a median of 0 hours of EN lost due to technical complications. The 0.5 hours lost in the continuous group equates to 2% of the 24 hour PPND. This discrepancy accounts for the lower average PPND (approximately 2%) of continuously fed dogs (98.4%) when compared with the intermittently fed group (100%).47

Metabolic problems include rapid absorption of high-carbohydrate solutions, which could result in hyperglycemia; osmotic diuresis; and ultimately nonketotic, hyperosmolar coma. This is referred to as the refeeding syndrome;90 we do not routinely observe this complication with enteral feedings. Metabolism of glucose also results in the production of CO2 and metabolic water; excess CO2 production can further compromise patients with pulmonary disease. If metabolic water is retained, it can contribute to hyponatremia and edema. Most of these complications can be prevented by acclimatization of the patient to the feeding solution, slow rates of administration, and not overfeeding. Additional monitoring and potential supplementation of electrolytes such as potassium, magnesium, calcium, and phosphate, may be required in critically ill patients. Urine or blood glucose concentrations should be monitored at regular intervals if hyperglycemia is suspected. Hyperglycemia can be managed by reducing nutrient flows or by giving insulin, as discussed in Chapter 25. Until there is more documentation (controlled studies) in the veterinary literature, evidence-based guidelines for enteral feeding in human adult patients41,91 should be reviewed by practitioners and their staff interested in providing nutrition support to veterinary patients.

Conclusions

• Early enteral nutrition may be beneficial to the veterinary patient, although further studies are needed in clinical populations.

• Early initiation of nutrition should be an integral part of the patient’s treatment plan consideration to supply enterocyte nutrition and protect the mucosal barrier.

• Both the continuous and intermittent methods of nasoenteric tube feeding can facilitate adequate nutrient intake with minimal GI complications in critically ill dogs.

• Additional research is needed to determine optimal diet formulations for different patient populations.

1 Abood S., Buffington C.A. Improved nasogastric intubation technique for administration of nutritional support in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1991;199:577-579.

2 Abood S., Mauterer J.V., McLoughlin M.A., et al. Nutritional support of hospitalized patients, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 1993.

3 Abrams J. The nutrition of the dog. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press. 1977:1-27.

4 Altman E., Cutee A.J. Compatibility of enteral products with commonly employed drug additives. Nutr Supp Serv. 1984;4:8-17.

5 Anderson R. Water balance in the dog and cat. J Small Anim Pract. 1982;23:588-598.

6 Beal M., Jutkowitz L.A., Brown A.J. Development of a novel method for fluoroscopically-guided nasojejunal feeding tube placement in dogs. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2007;17(3):S1.

7 Beal M., Mehler S.J., Staiger B.A., et al. Technique for fluoroscopic nasojejunal tube placement in dogs. Proceedings of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine. Canada: Montreal, Quebec, 2009. June 3–6th

8 Beal M., Mehler S.J., Staiger B.A., et al. Technique for percutaneous radiologic gastrojejunostomy in the dog. Proceedings of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, Canada: Montreal, Quebec, 2009. June 3–6th

9 Belknap D., Davison U., Flournoy D.J. Microorganisms and diarrhea in enterally fed intensive care unit patients. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1990;14:622-628.

10 Bone S., Mann F.A., Backus R.C., et al. Evaluation of Polymeric Diets delivered directly into the small intestine through surgically placed jejunostomy tubes. Proceedings of the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine, Montreal, Quebec, 2009. CAN; June 3-ttgh

11 Bright R. Percutaneous tube gastrostomy, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1990.

12 Buffington C., Blaisdell J. Effect of citrate solutions on enteral formula clot formation. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1989;13:14S.

13 Buffington C., Holloway C., Abood S.A. Normal dogs. St Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2004:24-25.

14 Buffington C. Nutritional support of the hospitalized patient. Video Forum for Small Anim Clin. 1989.

15 Butterworth C.J. The skeleton in the hospital closet. Nutr Today. 1974;9:4-8.

16 Campbell J., Jutkowitz L.A., Santoro K., Hauptman J., Holahan M.L., Brown A.J. Continuous versus intermittent delivery of nutrition via nasoenteric feeding tubes in critically ill canine and feline patients. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2010;20:232-236.

17 Carr C., Ling K.D., Boulos P., et al. Randomised trial of safety and efficacy of immediate postoperative enteral feeding in patients undergoing gastrointestinal resection. BMJ. 1996;312:869-871.

18 Cataldi-Betcher E., Seltzer M.H., Slocum B.A., et al. Complications occurring during enteral nutrition support: A prospective study. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1983;7:546-552.

19 Center S., Wilkinson E., Smith C.A., et al. 24-Hour urine protein/creatinine ratio in dogs with protein-losing nephropathies. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1985;187(8):820-824.

20 Chandler M., Guilford W.G., Lawoko C.R.O. Comparison of continuous versus intermittent enteral feeding in dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 1996;10(3):133-138.

21 Chandra R., Scrimshaw N.S. Immuno-competence in nutritional assessment. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980;33:2694-2697.

22 Chyka P., Seger D., Krezelok E.P., Vale J.A. Position paper: single-dose activated charcoal. Clin Toxicol. 2005;43(2):61-87.

23 Ciocon J., Galindo-Ciocon D.J., Tiessen C., Galinda D. Continuous compared with intermittent tube feeding in the elderly. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1992;16:525-528.

24 Clark C. Fluid Therapy, 2nd ed. Santa Barbara, Calif: American Veterinary Publications. 1975:601-609.

25 Crane S. Placement and maintenance of a temporary feeding tube gastrostomy in the dog and cat. Comp Cont Ed Vet Pract. 1980;10:770-780.

26 Crowe D. Enteral nutrition for the critically ill or injured patient: Part II. Comp Cont Ed Vet Pract. 1986;8:719-730.

27 Crowe D. Methods of enteral feeding in the seriously ill or injured patient: Part I. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 1985;3:1-6.

28 Daye R., Huber M.L., Henderson R.A. Interlocking box jejunostomy: A new technique for enteral feeding. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1999;35:129-134.

29 de Aguilar-Nascimento J., Kudsk K.A. Early nutritional therapy: the role of enteral and parenteral routes. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11(3):255-260.

30 Debraekeleer J., Gross K.L., Zicker S.C. Feeding nursing and orphaned puppies from birth to weaning, 5th ed. Topeka, Kan: Mark Morris Institute; 2010.

31 Della-Ferra M., Baile C.A., McLaughlin C.L. Feeding elicited by benzodiazepine-like chemicals in puppies and cats: Structure-activity relationships. Pharm Biochem Behav. 1980;12:195-200.

32 DeNovo R., Churchill J., Faudskar L., et al. Limited approach to the right flank for placement of a duodenostomy tube. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2001;37:193-199.

33 Edes T., Walk B.E., Austin J.L. Diarrhea in tube-fed patients: Feeding formulas not necessarily the cause. Am J Med. 1990;88:91-93.

34 Edney A.T., Smith P.M. Study of obesity in dogs visiting veterinary practices in the United Kingdom. Vet Rec. 1986;118:391-396.

35 Ford R. Nasogastric intubation in the cat. Comp Cont Ed for the Ann Health Tech. 1980;1:29-33.

36 Fulton R.J., Dennis J.S. Blind percutaneous placement of a gastrostomy tube for nutritional support in dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1992;201:697-700.

37 Gianotti L., Nelson J.L., Alexander J.W., Chalk C.L., Pyles T. Post injury hypermetabolic response and magnitude of translocation: prevention by early enteral nutrition. Nutrition. 1994;10(3):225-231.

38 Gottschlich M., Warden G.D., Michek M., et al. Diarrhea in tube-fed burn patients: incidence, etiology, nutritional impact, and prevention. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1988;12:338-345.

39 Gross K., Becvarova I., Debraekeleer J. Feeding nursing and orphaned kittens from birth to weaning, 5th ed. Topeka, Kan: Mark Morris Institute; 2010.

40 Grunow J., Christenson J.W., Moutos D. Contamination of enteral nutrition systems during prolonged intermittent use. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1989;13:23-25.

41 Guidelines for the use of parenteral and enteral nutrition in adult and pediatric patients. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 2002;26S:1SA-6SA.

42 Hacker R., Harvey-Banchik L.P. Prospective randomized control trial of intermittent versus continuous gastric feeds for critically ill trauma patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 2008;23:564-565.

43 Hadfield R., Sinclair D.G., Houldsworth P.E., et al. Effects of enteral and parenteral nutrition on gut mucosal permeability in the critically ill. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152(5):1545-1548.

44 Hayes-Johnson V. Tube feeding complications: Causes, prevention, therapy. Nutr Supp Serv. 1988;6:17-24.

45 Hiebert J., Brown A., Anderson R.G., et al. Comparison of continuous vs. intermittent tube feedings in adult burn patients. J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1981;5:73-75.

46 Hill RaS K.R. Energy requirements and body surface area of cats and dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2004;225:689-694.

47 Holahan M., Abood S.A., Hauptman J. Intermittent and continuous enteral nutrition in critically ill dogs: A prospective randomized trial. J Vet Intern Med. 2010;24:520-526.

48 Horn D., Chaboyer W., Schluter P. Gastric residual volumes in critically ill pediatric patients: A comparison of feeding regimens. Aust Crit Care. 2004;17:98-103.

49 Ireland L., Hohenhaus A.E., Broussard J.D., et al. A comparison of owner management and complications in 67 cats with esophagostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding tubes. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2003;39:241-246.

50 Jergens A. Diarrhea. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995.

51 Kaneko J. Serum proteins and the dysproteinemias. In: Kaneko J., editor. Clinical biochemistry of the domestic animals. 4th ed. New York: Academic Press; 1989:142-165.

52 Kaur N., Gupta M.K., Minocha V.R. Early enteral feeding by nasoenteric tubes in patients with perforation peritonitis. World J Surg. 2005;29(8):1023-1027.

53 Kenny D., Goodman P. Care of the patient with enteral tube feeding: an evidence-based practice protocol. Nurs Res. 2010;59:S22.

54 Kleiber M. Body size and metabolic rate. Physiol Rev. 1947;27:511.

55 Kocan M., Hickisch S.M. A comparison of continuous and intermittent enteral nutrition in NICU patients. J Neurosci Nurs. 1986;18:333-337.