Biopsy Principles

A biopsy refers to a procedure that obtains a tissue specimen for microscopic (i.e., histopathologic) analysis to establish a precise diagnosis. Histopathologic interpretation of tissue removed from a tumor is not infallible and is highly dependent on the quality of the biopsy sample submitted. Therefore it is important to understand basic principles of biopsy procurement and submission in order to obtain an accurate diagnosis. If the tissue diagnosis is incorrect, all subsequent steps in the treatment of the patient will also be incorrect.

Fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is a simple and rapid way to obtain information about a tumor and is often the first step in the diagnostic work-up (see Chapter 7). Results of FNAC help guide the diagnostic tests for staging. Studies have shown that FNAC is a reliable and useful method to guide further work-up when neoplasia is suspected or, in many cases, to help rule out neoplasia altogether.1,2 Nonetheless, FNAC gives only limited information and may be nondiagnostic or equivocal. Inflammation, necrosis, and hemorrhage may result in cytopathologic changes that do not accurately represent the underlying disease process. Histologic confirmation is therefore required for definitive diagnosis of neoplasia.

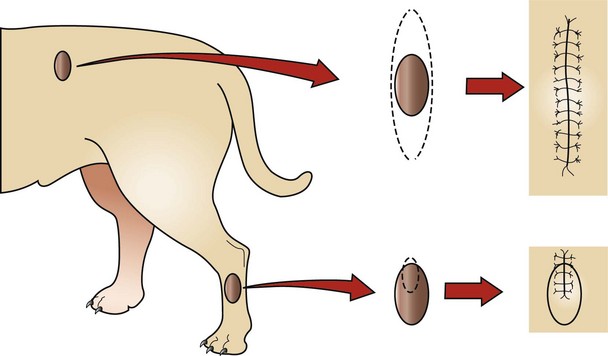

Many techniques are available for obtaining tissue specimens—ranging from needle-core techniques to complete excision. The choice of technique depends on the anatomic location of the tumor, the patient’s overall health, the suspected tumor type, and the clinician’s preference. Biopsy techniques can be grouped under one of two major categories: pretreatment biopsy (e.g., needle core biopsy, punch biopsy, wedge biopsy) or excisional biopsy. Pretreatment biopsy is performed in order to obtain additional information about the tumor prior to definitive treatment. Posttreatment (i.e., excisional) biopsy refers to the process of obtaining histopathologic information following surgical removal of the tumor. Excisional biopsy is best used to obtain a more complete picture of the disease process (e.g., histologic subtype, tumor grade, degree of invasion into regional vasculature and lymphatics) and provides an opportunity to evaluate completeness of excision. It is rarely the best first step in obtaining a tissue diagnosis. Although excisional biopsy is attractive to many clinicians because it allows for definitive treatment and diagnosis in one step, it is often used inappropriately in the management of a cancer patient, resulting in incomplete surgical margins. Incomplete surgical margins may result in local recurrence, the need for radiation therapy, or a wider, more extensive surgery. All of these sequelae represent compromise of the optimum treatment pathway for the patient and will involve more morbidity and expense than a properly performed first excision. The issue to be determined before surgery is: how aggressive should the surgery to remove the tumor be? It is intuitive that wide, ablative surgery (e.g., body wall resection) would be inappropriate for a simple lipoma. It also follows that marginal excision (“shell out”) is inappropriate for definitive treatment of an aggressive tumor, such as a soft tissue sarcoma. Thus thorough knowledge of the tumor type is imperative prior to attempting surgical excision. The best way to obtain this information is often via pretreatment biopsy.

Specific indications for pretreatment biopsy are as follows:

1. When fine-needle aspirate cytology is nondiagnostic or equivocal.

2. When the type of recommended treatment (radiation versus chemotherapy versus surgery) would be altered by knowledge of the tumor type or grade.

3. When the extent of recommended treatment (ablative surgery versus wide excision versus marginal excision) would be altered by knowledge of the tumor type or grade.

4. When the tumor is in a difficult area to reconstruct (maxillectomy, locations requiring extensive flaps, head and neck) and planning is needed to prepare the patient and client appropriately.

5. When knowledge of the tumor type or grade would change the owner’s willingness to go forward with curative-intent treatment.

If any one of the listed criteria is met, a pretreatment biopsy should be pursued.

There are occasions when pretreatment biopsy would be contraindicated. These include cases when the type of treatment or extent of surgery would not be changed by knowing the tumor type (e.g., testicular mass, solitary splenic mass) or when the surgical procedure to obtain the biopsy is as risky as definitive removal (e.g., spinal cord biopsy). In these cases, the patient would best be served by excisional biopsy of the tumor if staging results support this choice.

Biopsy Methods

The more commonly used methods of tissue procurement are needle core biopsy, punch biopsy, incisional (wedge) biopsy, and excisional biopsy.

Needle Core Biopsy

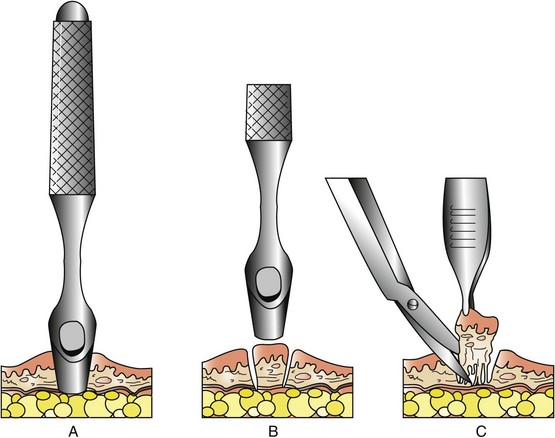

Needle core biopsy utilizes various types of needle core instruments (e.g., Tru-Cut [Baxter General Healthcare, Deerfield, IL] or ABC needle [Kendall Sherwood-Davis & Geck, St. Louis, MO]) to obtain soft tissue (Figure 9-1). Most of these needles are manually operated, although spring and pneumatically powered needles are available as well. Specialized core instruments are used for bone biopsies and will be covered in Chapter 24. These instruments are generally 14-g in diameter and procure a piece of tissue that is about 1 mm wide and 1.0 to 1.5 cm long. In spite of this small sample size, the structural relationship of the tissue and tumor cells can usually be visualized by the pathologist. Virtually any accessible mass can be sampled by this method. It may be used for externally located lesions or for deeply seated lesions (e.g., in the kidney, liver, or prostate) with image-guidance via closed methods or at the time of open surgery.

Figure 9-1 Mechanism of action of needle core biopsy needle for typical nodular tumor. A, A small skin incision is made with a Number 11 blade to allow insertion of the instrument. With the instrument closed, the outer capsule is penetrated. B, The outer cannula is fixed in place, and the inner cannula with the specimen notch is thrust into the tumor. The tissue then protrudes into the notch. C, The inner cannula is now held steady while the outer cannula is moved forward to cut off the biopsy specimen. D, The entire instrument is removed closed with the tissue contained within it. E, The inner cannula is pushed ahead to expose the tissue in the specimen notch.

The most common usage of the needle core biopsy is for externally palpable masses. Except for highly inflamed and necrotic cancers (especially in the oral cavity), in which incisional biopsy is preferred, most biopsies can be done on an outpatient basis with local anesthesia and sedation. The area to be biopsied should be clipped of hair and sterilely prepared. The skin or overlying tissue is prepared as for minor surgery. If the overlying tissue (usually skin and muscle) is intact, it is anesthetized using local anesthetic in the region that the biopsy needle will penetrate. Tumor tissue itself is very poorly innervated and generally does not require local anesthesia. The mass is then fixed in place with one hand or by an assistant. A small 1- to 2-mm stab incision is made in the overlying skin with a scalpel blade to allow insertion of the biopsy instrument. The stab incision is necessary to prevent dulling of the needle tip and allow better penetration into the underlying tissue. Through the same skin hole, several needle cores are removed from different sites to get a “cross-section” of tissue types within the mass. The stab incision can be sutured with a single interrupted suture. The tissue is gently removed from the instrument with a scalpel blade or hypodermic needle and placed in formalin. For smaller-gauge biopsy needle instruments, the tissue may be flushed off the needle with saline. Samples may be gently rolled on a glass slide for cytologic preparations before fixation. With experience, the operator can generally tell from the appearance of the core sample whether diagnostic material has been attained. Small, discontinuous bits of tissue and fluid within the trough will only rarely be diagnostic and usually imply the need for incisional biopsy. Soft tissue sarcomas in particular may not yield good tissue cores because of necrosis and fibrous septa that often permeate the mass. Cystic masses are also problematic.

Needle biopsy tracts are of minimal risk for local tumor seeding but should be removed en bloc with the tumor at subsequent resection. Therefore it is important to plan where the stab incision and needle biopsy tract are placed in order to make the subsequent excision simpler. Avoid excessive tunneling through uninvolved tissues by choosing the most direct path from the skin to the tumor to obtain a representative sample.

Many of these needles are “disposable” with plastic casings and therefore cannot be steam sterilized. It is not uncommon, however, for veterinary practices to resterilize these instruments (using ethylene oxide or hydrogen peroxide gas) and use them repeatedly until they become dull.

Needle core biopsy instruments are inexpensive and easy to use, and needle core biopsy procedures can be performed as outpatient procedures. They are generally more accurate than cytology but likely have lower accuracy than larger incisional or excisional biopsy, especially when a tumor is heterogeneous, inflamed, or cystic or contains a large amount of necrosis. It is important to understand that for a 5-cm diameter mass, one needle core biopsy sample represents less than 1% of the tumor tissue. The smaller the biopsy specimen obtained, the less representative it may be for the entire tumor.

Needle core biopsy can be performed with the aid of image-guidance (discussed in greater detail later). Utilization of image-guidance for needle core biopsy is helpful for obtaining tissue from deeply seated lesions. Ultrasound-, fluoroscopic-, and computed tomographic-assistance may be used to obtain samples from tumors located in areas where percutaneous biopsy would be risky or unlikely to yield a representative sample. In situations in which the lesion is located within a body cavity, the risk of tumor seeding from uncontrolled hemorrhage or fluid leakage as a result of image-guided biopsy must be taken into account when determining if image-guided needle core biopsy techniques hold an advantage over more direct access in a given circumstance.

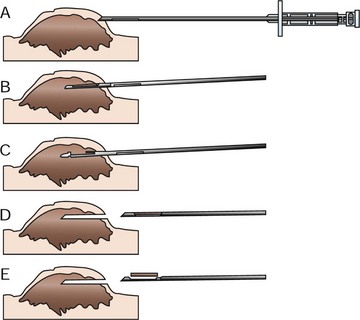

Punch Biopsy

Punch biopsy tools were originally designed for biopsy of the skin (Figure 9-2). They deliver a shorter and wider (2 to 8 mm) biopsy than does the needle core technique. They can be used on any external tumor (skin, oral, perianal) or tumors where there is direct access (e.g., liver biopsy during laparotomy). Preparation of the site is the same as for needle core biopsy. If the lesion is cutaneous, the punch biopsy instrument is placed on the surface of the area of interest and rotated back and forth using pressure to penetrate the involved tissue. If the skin is intact over the tumor, the skin is first incised using a scalpel. The punch is then introduced through the skin incision to the surface of the tumor. Once the punch has cut into the tumor, the core is gently lifted and the base of the core is cut off with scissors. One or two sutures may be placed to close the skin incision.

Incisional Biopsy

Incisional biopsy is utilized when fine-needle cytology or needle core biopsy has not yielded or is unlikely to yield diagnostic material (Figure 9-3). Additionally, it is preferred for ulcerated and necrotic lesions because larger samples can be obtained, making it more likely to sample representative areas. Most tumors are poorly innervated and may be biopsied without the need for local anesthesia or sedation as long as the overlying normal skin and tissue has been anesthetized. Preparation involves clipping the hair over the incision site. After performing a sterile surgical preparation, surgical drapes are used to protect the field from the surrounding environment. Under sterile conditions, the skin over the tumor, if intact, is incised and a wedge of tumor tissue is removed from the mass. It is not necessary to remove a wedge of intact skin overlying the tumor if it appears to be normal and not fixed to the underlying tumor. The surgeon should confirm at the time of the biopsy that they have not simply removed a small section of the reactive tissue surrounding the tumor. This can be difficult in some cases, however, because most tumors have coloration and texture that is distinct from the surrounding normal and reactive tissue. If needed, “touch-prep” cytology slides can be made using the resected tissue prior to fixation to confirm that neoplastic cells are present in the removed tissue.

Figure 9-3 Excisional (top) contrasted with incisional (bottom) biopsy. The top tumor may be as easy to remove as to biopsy, and removal may not negatively influence other possible treatments (e.g., more surgery, radiation). The bottom tumor, however, requires knowledge of the tumor type prior to excision because inappropriate removal could compromise a subsequent aggressive excision (short of amputation). Note that the biopsy incision is in a plane that would be included in a subsequent resection.

Many authors have recommended that the surgeon acquire a composite biopsy of normal and abnormal tissue to ensure accuracy in diagnosis on histopathologic examination. Although this may be helpful to the pathologist in benign skin disease and subtle lesions, it is not recommended in cases where neoplasia is suspected because this may compromise the surgical margin needed to remove the mass entirely at the time of definitive surgery and exposes previously uninvolved tissues to freshly incised tumor. Instead, a representative sample of the tumor itself should be submitted. This may require obtaining multiple samples via the same incision to ensure that a representative sample has been achieved. Care must be taken to ensure that any biopsy tract (incisional or other) will not compromise subsequent curative resection or contaminate uninvolved tissue needed for reconstruction. The surgeon should avoid wide exposure of uninvolved tissue planes that could become contaminated with released tumor cells. Small incisions, even through expendable muscle bellies, are preferred to contaminating the entire intramuscular compartment. The incisional biopsy tract is always removed in continuity with the tumor at the time of curative-intent resection.

Specialized Biopsy Techniques

Specialized biopsy techniques will generally be covered under the specific individual tumors. However, some general comments follow.

Endoscopic Biopsies

Endoscopic biopsy techniques use flexible or occasionally rigid scopes that allow visualized or blind biopsy of hollow lumens, especially gastrointestinal, respiratory, and urogenital systems. Although these techniques are convenient, cost effective, and generally safe, they may suffer from inadequate visualization and limited biopsy sample size when compared with other techniques. For example, an endoscopic biopsy result of ulcerative gastritis in a dog with a firm, infiltrative mass of the lesser curvature of the stomach does not rule out gastric adenocarcinoma.

Laparoscopy and Thoracoscopy

Evaluation of the abdomen and thorax via minimally invasive techniques, when performed by an experienced operator, can procure tissue for biopsy and yield important information regarding the locoregional stage of disease. Additionally, laparoscopic- and thoracoscopic-assisted removal results in smaller incisions and rapid recovery times when compared with open procedures. The option to convert to an open procedure is available if problems are encountered that cannot be adequately addressed using minimally invasive methods. As operators become more proficient at these techniques, more options become available for tumor removal.

Image-Guided Biopsy

Diagnostic imaging has greatly expanded the ability to stage various neoplasias. The use of positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) in veterinary medicine has also led to significant advances in sentinel node mapping, novel staging methods, and the ability to assess response to treatment. In addition, the use of radiographic, fluoroscopic, ultrasonographic, computed tomographic, and magnetic resonance image–guided needle aspirates or core biopsies can obviate the need for more invasive diagnostic procedures. Common sites for image-guided biopsy include lung, kidney, liver, spleen, prostate, and, more recently, brain.

Excisional Biopsy

Excisional biopsy is utilized when definitive treatment would not be altered by knowledge of tumor type (e.g., “benign” skin tumor, solitary splenic mass, testicular tumor). It is more frequently performed than indicated, but, when used on properly selected cases, it can be both diagnostic and therapeutic, as well as cost effective.

General Guidelines for Tissue Procurement and Fixation

• When properly performed, a pretreatment biopsy will not negatively influence survival.3 The metastatic cascade involves a series of complex events that are not altered by the number of neoplastic cells in circulation. On the other hand, neoplastic cells can contaminate the local tissues surrounding the mass and in some cases, successfully attach and grow within these normal tissues. Careful hemostasis, obliteration of dead space, and avoidance of seromas or hematomas will minimize local contamination of the incisional biopsy site. Definitive surgery to remove the tumor along with the associated biopsy tract should take place as soon as possible following the biopsy procedure. If possible, surgical drains should not be placed in biopsy sites because the drain tract can become contaminated with tumor cells and seed them through uninvolved tissue planes. In particular, care should be taken not to “spill” cancer cells within the thoracic or abdominal cavities during biopsy where they may seed pleural or peritoneal surfaces.

• When biopsies are performed on the legs or the tail, the incision should be longitudinal and not transverse. Transverse incisions are much harder to completely resect. If a biopsy is near midline, the incision should be oriented parallel to midline.

• Avoid taking the junction of normal and abnormal tissue for pretreatment biopsy unless a margin is likely necessary for differentiating benign or malignant tumors (e.g., perianal adenoma or adenocarcinoma often can only be differentiated histologically by observing local tissue infiltration). Care should be taken not to incise normal tissue that cannot be resected or would be used in reconstructing the surgical defect. Avoid biopsies that contain only ulcerated or inflamed tissues.

• The larger the sample, the more likely it is to be diagnostic. Tumors are not homogeneous and usually contain areas of necrosis, inflammation, and reactive tissue. Several samples from one mass are more likely to yield an accurate diagnosis than a single sample.

• Biopsies should not be obtained with electrocautery because it tends to deform (autolysis or polarization) the cellular architecture. Electrocautery is better utilized for hemostasis after blade removal of a diagnostic specimen.

• Care should be taken not to unduly deform the specimen with forceps, suction, or other handling methods prior to fixation.

• Intraoperative diagnosis of disease by frozen sections, although not routinely available in veterinary medicine, has enjoyed widespread use in human oncology. Special equipment and training are required for this technique to be fully utilized. One study in veterinary medicine revealed an accurate and specific diagnosis rate of 83%.4

• If evaluation of excisional margins is desired, the surgeon should indicate the surgical margin on the specimen using tissue ink. Several commercial inking systems are available for this use. The resected tissue should be blotted with a paper towel because dyes will adhere better to the tissue when it is slightly tacky. The tissue ink is “painted” on the surgical margins using a cotton swab. The dye is allowed to dry for up to 20 minutes before the tissue is placed in formalin. Tissue already fixed in formalin can be marked; however, dye adherence is lessened and drying time is extended. When the pathologist sees tumor cells at the inked edge, it is a certainty that tumor cells have been left in the patient. Different-colored inks can also be used to denote different sites on the tumor, such as proximal margin or deep margin near nerve. Even with inking, proper fixation, and processing, the clinician must realize the entire margin will not be examined by the pathologist. Rather, representative sections will be obtained from the inked margin. Therefore any guidance that the clinician can give to the pathologist as to the most important sections to look for tumor cells will help the pathologist pay closer attention to such areas. It is vital that the pathologist and the clinician communicate if the pathology report is confusing or does not match the clinical picture. Of course, margin evaluation is only necessary for excisional biopsy or curative-intent surgery and does not apply to needle core biopsies or incisional biopsies, which by definition will have inadequate margins. Incomplete surgical resection of malignant disease is best detected early so that further surgery or other adjuvant therapies can be instituted immediately, as opposed to waiting for local recurrence or metastasis.

• Stainless steel vascular clips in the resected specimen will damage the microtomes used by the pathology laboratory. Remove them before the tissue is submitted.

• Proper fixation is vital. Tissue is generally fixed in 10% buffered neutral formalin with 1 part tissue to 10 parts fixative. If more than one lesion has been biopsied, they should each be placed in a separate container. Certain tissues such as eye, nerve, and muscle may require special fixation techniques. The clinician may want to consult with the pathologist on how to submit tissue for special circumstances.

• Tissue should not be thicker than 1 cm or it will not fix properly. Masses greater than 1 cm in diameter can be sliced like a loaf of bread, leaving the deep-inked margin intact, to allow fixation. Extremely large masses can be incompletely sliced as described above, fixed in a large bucket of formalin for 2 to 3 days and then shipped in a container with 1 part tissue to 1 part formalin. A less ideal but alternative approach is to have the surgeon take representative smaller samples from the mass (e.g., soft and hard pieces, red and pale pieces, deep and superficial pieces) in the hope that one of them is diagnostic. The rest of the mass can be saved in the clinic in formalin in case more tissue needs to be evaluated. This extra tissue should never be frozen. Freezing causes severe tissue artifact.

• A detailed history should accompany all biopsy requests. Interpretation of surgical biopsies is a combination of art and science. Without vital diagnostic information (e.g., signalment, history of recurrences, invasion into bone, rate of growth), the pathologist will be significantly compromised in his or her ability to deliver accurate and clinically useful information.

• A veterinary-trained pathologist is preferred over a pathologist trained in human diseases. Although many cancers are histologically similar across species lines, enough differences exist to result in interpretive errors.

In 2011, the American College of Veterinary Pathologists, along with several medical and surgical oncologists, published a comprehensive set of recommendations and guidelines for submission, trimming, margin evaluation, and reporting of tumor biopsy specimens.5 This seminal paper was the first collaborative attempt to standardize pathology reporting in veterinary oncology and has been endorsed by a large international group of veterinary pathologists and oncology specialists. It is recommended that clinicians utilize diagnostic laboratories that adhere to these guidelines so that results are standardized and easier to interpret.

Interpretation of Results

The pathologist’s task is to determine (1) tumor versus no tumor, (2) benign versus malignant, (3) histologic type, (4) grade (if applicable), and (5) margins (if excisional). Making an accurate diagnosis is not as simple as putting a piece of tissue in formalin and waiting for results. Many pitfalls can occur that render the end result inaccurate. Potential errors can take place at any level of the process, and it is up to the clinician to interpret the full meaning of the biopsy result. In cases in which the biopsy result does not correlate with the clinical scenario, a second opinion should be pursued. A study published in 2009 reviewed first and second opinion histopathology reports.6 In 70% of cases, there was diagnostic agreement between first and second opinion results. In 20% of cases, there was partial agreement where the diagnosis did not change, but information such as grade or presence of lymphatic or vascular invasion was disparate. In 10% of cases reviewed, there was complete diagnostic disagreement. Of these, 7% were a disagreement between malignant versus nonmalignant and 3% were disagreements about cell origin. If the biopsy result does not correlate with the clinical scenario, the following several options are possible:

1. Call the pathologist and express your concern over the biopsy result. This exchange of information should be helpful for both parties and not looked on as an affront to the pathologist’s authority or expertise. It may lead to the following:

a. Resectioning of available tissue or paraffin blocks.

b. Special stains for further discrimination of tumor types (e.g., toluidine blue for mast cells).

2. If the tumor is still present in the patient and particularly if widely varied options exist for therapy, a second (or third) biopsy should be performed.

A carefully performed, submitted, and interpreted biopsy is the most important step in management and subsequent prognosis of the patient with cancer. The biopsy report is key in decisions regarding prognosis, therapeutic options, and overall case management. All too often tumors are not submitted for histologic evaluation after removal because “the owner didn’t want to pay for it.” Histopathologic interpretation should not be an elective owner decision. Instead, it should be as automatic as closing the skin after surgery. The charge for submission and interpretation of the biopsy should be included in the surgery fee if need be, but histopathology interpretation is not optional. Because of increasing medicolegal concerns, it is not medical curiosity alone that mandates knowledge of tumor type. Understanding how and when to perform a biopsy, how to submit a biopsy specimen, and how to interpret the report is of paramount importance in the treatment of veterinary cancer patients.

References

1. Ghisleni, G, Roccabianca, P, Ceruti, R, et al. Correlation between fine-needle aspiration cytology and histopathology in the evaluation of cutaneous and subcutaneous masses from dogs and cats. Vet Clin Path. 2006;35(1):24–30.

2. Sharkey, LC, Wellman, ML. Diagnostic cytology in veterinary medicine: A comparative and evidence-based approach. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31(1):1–19.

3. Klopfleisch, R, Sperling, C, Kershaw, O, et al. Does the taking of biopsies affect the metastatic potential of tumors? A systematic review of reports on veterinary and human cases and animal models. Vet J. 2011;190(2):e31–e42.

4. Whitehair, JG, Griffey, SM, Olander, HJ, et al. The accuracy of intraoperative diagnoses based on examination of frozen sections. A prospective comparison with paraffin-embedded sections. Vet Surg. 1993;22(4):255–259.

5. Kamstock, DA, Ehrhart, EJ, Getzy, DM, et al. Recommended guidelines for submission, trimming, margin evaluation, and reporting of tumor biopsy specimens in veterinary surgical pathology. Vet Pathol. 2011;48(1):19–31.

6. Regan, RC, Rassnick, KM, Balkman, CE, et al. Comparison of first-opinion and second-opinion histopathology from dogs and cats with cancer: 430 cases (2001-2008). Vet Comp Oncol. 2010;8(1):1–10.