Chapter 51 Pernio (Chilblains)

Pernio, commonly known as chilblains, is a cold-induced localized inflammatory condition presenting as skin lesions predominantly on unprotected acral areas. Typically there is swelling of the dorsa of the proximal phalanges of fingers and toes (Fig. 51-1). Pernio is a Latin term meaning “frostbite.” Chilblains is an Anglo-Saxon term used in older literature and means “cold sore.” The tissue and vascular damage is less severe in pernio than in frostbite, in which the skin is actually frozen. The numerous names that were used to describe this syndrome created much confusion and misunderstanding of this entity1 (Box 51-1). In the mid-1800 s, there were attempts to better classify the disease2 and in 1894, Corlett was the first to describe the clinical characteristics of pernio, which he called dermatitis hiemalis.3

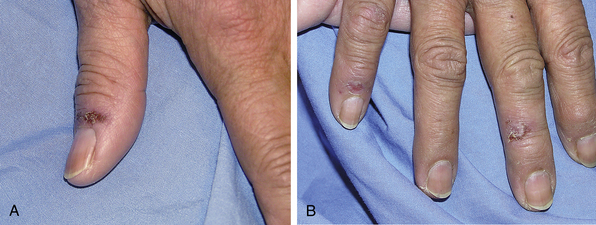

Figure 51-1 Typical changes of pernio on dorsal portion of toes (A) and on pads of toes (B). Distribution around nail beds (A) and swollen toes with brownish yellow lesions (B) are characteristic of pernio. At this stage, affected extremities often itch and burn.

Epidemiology

The first epidemiological study to explicate the prevalence of chilblains and its impact on productivity in servicewomen was carried out in 1942 by the U.S. Medical Department of the War Office.4 The study concluded that at least 50% of questionnaire participants had chilblains by age 40 during World War II (1939-1943). Although pernio is most common in young women, it has also been reported in all ages and both sexes.5–8 The number of reported cases of pernio is higher during times of wet near-freezing weather, and less common in dry freezing weather or in a bitterly cold climate.9 Pernio is most commonly encountered in the northern and western parts of the United States; isolated cases have been reported in warmer climates in times of cooler damp weather.5,6,10–12

As shown by a recently reported cross-sectional study conducted by the U.S. Army, the yearly rate of cold weather injuries declined from 38.2/100,000 in 1985 to 0.2/100,000 in 1999.13 This and other observations from clinical practice suggest that the disease is becoming less common with higher standards of home and workplace heating and greater use of appropriate clothing during the cold winter months. Also, the study confirmed previous investigations that cold weather injuries in African American men and women occurred approximately 4 and 2.2 times as often, respectively, as in their Caucasian counterparts.

Pathophysiology

The first response to cold exposure is vasoconstriction in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Heat loss is minimized by shutting down distal capillary beds and diminishing blood supply to the acral portions of the extremities to maintain central body temperature. Stasis and shunting of blood flow away from the superficial vessels occurs secondary to arteriolar constriction, venular relaxation, and cold-associated increased blood viscosity. The result of these changes is superficial tissue anoxia and ischemia.7,9,14–16 The arteriolar vasoconstriction described in pernio has been demonstrated in pathological and radiographic studies.6,7 Female predominance may be related to increased responsiveness of their cutaneous circulation to cold. Indeed, there is a higher frequency of vasomotor instability, cold hands and feet, and Raynaud’s phenomenon in women.8,17–19

Humidity has an important role in the pathophysiology of pernio because it enhances air conductivity, promoting heat loss from the skin.5,8 Most individuals tolerate exposure to nonfreezing damp cold, but others may experience pernio, Raynaud’s phenomenon, acrocyanosis, or cold urticaria.8,18 The clinical manifestations of cold injuries are related to duration, severity, and dampness of cold exposure as well as the individual’s underlying predisposition to cold injury and the stage at which medical attention was sought.7 The exposed skin of affected subjects remains cool longer and warms slower than that of controls, further highlighting the importance of individual susceptibility for development of pernio after cold exposure.6–8,20 The increased incidence of pernio among relatives of affected patients suggests the possibility of genetic predisposition.4 Several other conditions have been proposed to promote vulnerability to the disease (Box 51-2).

Why one patient exposed to cold develops Raynaud’s phenomenon and another pernio is unclear. Raynaud’s phenomenon and pernio frequently coexist in the same patient, so these diseases may be part of a continuum, with Raynaud’s phenomenon representing acute and readily reversible vasospasm, and pernio representing more prolonged vasospasm with more chronic changes.8,21

A number of conditions have been associated with pernio. Weston and Morelli reported the presence of cryoproteins in four of eight children presenting with pernio.11,22 Since cryoproteins and cold agglutinins may be detected transiently after viral infections, they hypothesized that exposure to cold wet weather during the brief cryoproteinemia may lead to exaggerated tissue injury manifesting as pernio. Pernio has been described both in women with large amounts of leg fat and in women with inadequate fat pads, as seen in anorexia nervosa.5–7

The possibility that pernio may be a manifestation of a pre-leukemic state, namely the chronic myelomonocytic type, has been suggested in several case reports in which skin lesions and a clinical course similar to that of pernio were observed.5,23–25 In some of these cases, leukemia was diagnosed 6 to 36 months after the pernio-like illness.

Viguier et al. reported observations over 38 months on a cohort of 33 patients with severe chilblains, defined as duration of lesions greater than 1 month.21 Two thirds of the patients had clinical and/or laboratory features supporting a diagnosis of connective tissue disorders: 12 patients had systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and 10 patients presented with at least one of the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for SLE at the time of the diagnosis of pernio. In the latter group, all patients except one had positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) titers. These observations led the authors to conclude that when the lesions persist beyond the cold season, perniotic lesions may be a clue to underlying SLE. Therefore, targeted laboratory investigations to search for conditions listed in Box 51-2, as well as long-term follow-up, are recommended for patients who present with pernio.26

Histopathology

Although not routinely required to establish the diagnosis, biopsies are occasionally sought by healthcare providers unfamiliar with the disease.27 The histopathological features of perniotic lesions may vary depending upon the chronological stage of the disease and presence or absence of superimposed secondary pathology such as infection or ulceration.7,28,29

The characteristic histopathological features of pernio are usually seen in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue, but are not pathognomonic. These consist of edema of the papillodermis, vasculitis characterized by perivascular infiltration of the arterioles and venules of the dermis and subcutaneous fat by mononuclear and lymphocytic cells, thickening and edema of blood vessel walls, fat necrosis, and chronic inflammatory reaction with giant cell formation.8 Not all these changes are necessarily present, and fat necrosis and giant cell formation are frequently absent. The most consistent feature is perivascular lymphocytic or mononuclear infiltrates.28

Repeated episodes of vasospasm or prolonged vasospasm may cause tissue anoxia, thus causing the identical histopathological picture that occurs in pernio.1 The histological pattern of pernio lesions may mimic cutaneous vasculitis but typically lacks fibrinoid deposition, inflammatory cells in the vessel wall, and thrombosis, typical of true vasculitis.5–7,11,27,29–33 Blood vessels in long-standing pernio resemble those of any chronic occlusive vascular disease. The occlusion and fibrosis present are due to long-standing injury; this histopathological appearance may be seen in many other types of vascular disease.

Review of published case series and case reports support the notion that pernio may display different and loosely related histological features.33 Cribier et al. retrospectively compared the biopsies of hand lesions from 17 patients with chilblains to those of 10 patients with proven SLE and associated pernio-like hand lesions.27 The study included only acute lesions (<1 month duration) occurring during the cold period of the year. The most characteristic finding in chilblains (47% of cases) was the association of edema and reticular dermis infiltrate that showed a perieccrine reinforcement: dermal edema (70% of chilblains lesions vs. 20% of SLE lesions), superficial (papillary) and deep (reticular) infiltrate (82% vs. 80%), and deep perieccrine reinforcement (76% vs. 0%). The infiltrate was composed primarily of T cells, which were predominantly CD3+. Remarkably, 29% of the chilblain lesions in this group showed evidence of microthrombi (compared to 10% in the lupus group), usually a feature seen in vasculitis, and 6% had conspicuous vacuolation (compared to 60% in the lupus group).

In another study, Viguier et al. prospectively studied 33 patients with severe prolonged chilblains (i.e., lesions persisted >1 month) and attempted to differentiate the histopathological characteristics of lesions of “idiopathic” pernio from those of pernio-like lesions in patients with connective tissue diseases or lupus pernio.21 Skin punch biopsies were performed on 5 of 11 patients of the “idiopathic” pernio group, and these showed deep dermal, perisudoral lymphocytic infiltrate (100%), dermal edema (75%), keratinocyte necrosis (62.5%), and keratinocyte vacuolization (50%). In comparison, biopsies from 7 of the 12 patients with the diagnosis of SLE (LE chilblain), demonstrated perisudoral cellular infiltrate in only two patients (vs. 8/8 in the “idiopathic” chilblains group; P = .007). Biopsy is rarely needed to make the diagnosis of pernio, but a biopsy may be helpful in differentiating atheromatous embolization from pernio in an ischemic-looking lesion (Fig. 51-2).

Clinical Features

Pernio most commonly affects females in adolescence and early adulthood, but may occur at any age and in either gender. The lesions typically affect the acral areas of the toes and the dorsa of the proximal phalanges but may involve the nose, ears, and thighs1–4,7,21,34–38 (Fig. 51-3). The location of the lesions seems to depend on occupation, lifestyle, and clothing habits. Hands and fingers appear more commonly affected in milkers and gardeners, the buttocks have been involved in women driving tractors in winter, and involvement of the lateral thighs have been described in women who wear thin pants and ride horses or motorcycles in winter.3,18,39–44 There was a recent report of perniotic lesions on the hips of young girls wearing tight-fitting jeans with a low waistband.45 The distal shins and calves are common sites of involvement in young women who wear short skirts.46 Facial lesions have been described in infants and rarely in adults.21,47

Figure 51-3 Typical appearance of pernio. Note characteristic bulbous swelling and brownish yellow appearance of left third toe. Flaking, itching, burning, and pain are common.

Typically the initial presentation is one of acute pernio, where the lesions appear during the cold months and disappear when the weather warms up. This may recur for several years and follows a similar seasonal pattern.7,8 Lesions vary in shape, number, and size and usually are associated with functional symptoms such as itching, burning, or pain. They can be described as brownish, yellow, or cyanotic on a base of doughy subcutaneous swelling or erythema (see Figs. 51-1 and 51-3). They may be cool to the touch or cooler than surrounding skin. Acute lesions may be self-limited and resolve within a few days to few weeks (especially in children) unless cold exposure persists, the lesions become infected, or the skin is broken by iatrogenic causes such as self-treatment with severe heat or vigorous massage.38,48 Otherwise, ulceration is not common in acute pernio, and when it happens, the lesions are usually shallow with a hemorrhagic base7,8 (see Fig. 51-2).

Chronic pernio ensues if repeated and prolonged exposure to cold persists throughout the acute phase and/or the patient goes through several seasons of acute pernio. The lesions of chronic pernio are similar to those seen in acute pernio but, if they occur over many seasons, may be associated with scarring, atrophy, permanent discoloration, and possibly ulceration (see Fig. 51-2). Initially, pernio may start late in the fall or early winter and resolve in early spring. If left untreated, the lesions of pernio may start earlier in the cold season and resolve later, until eventually all seasonal variation is lost.

Pernio tends to be more severe in adults and may, if left untreated, eventually cause macrovascular occlusive disease.6,8 Children, on the other hand, tend to have recurrent acute pernio over several seasons.38 Although most children outgrow the disease, middle-aged individuals presenting with pernio may occasionally recall a history of acute pernio during childhood. Several different forms of pernio have been described.

Milker’s pernio usually affects the hands and could be debilitating and force the affected individual to quit milking42 (Fig. 51-4). Kibe is defined as a chapped or inflamed area on the skin, especially on the heel, resulting from exposure to cold or an ulcerated chilblain.49 This has been described in overweight women who ride horses and wear tight pants, in women who ride motorcycles and wear thin pants, and in men who cross cold rivers with their thighs inadequately clothed.18,39 Lesions tend to localize on the outer thighs and often cause severe pain and disability. The pain may last up to a week and usually resolves once the lesions heal.18 A similar form has been described in women who drive tractors in winter, who tend to have lesions on the buttocks.44

Figure 51-4 This woman was exposed to a cold wet climate, resulting in pernio. Note brown and yellow flaking lesion on thumb (A) and healing lesions on index and ring fingers (B).

Lupus pernio applies to papular lesions involving the extremities and is associated with SLE.50 Whether this is a subtype of pernio or a pernio-like lupus manifestation remains controversial. Some authors suggested that most lupus pernio patients have lesions on the hands, but this anatomical localization was not a differentiating factor between idiopathic pernio and lupus pernio according to others.8,21,26 Features that suggest pernio secondary to SLE include onset of pernio during the third decade, female sex, African origin, and presence of pernio long after the cold weather has abated.

Erythrocyanosis affects adolescent girls and young women and typically involves the lower extremities. Some have classified this as the “nodular chronic form” of pernio; lesions take on a swollen, dusky red appearance.8

Diagnosis

Pernio usually is not difficult to diagnose. A comprehensive history and complete physical exam are the primary means by which the diagnosis of pernio can be correctly established. Chronological correlation between nonfreezing cold and onset of typical lesions that improve with onset of warm weather should strongly suggest the diagnosis.

Within hours of exposure to damp cold, and commonly at the onset of winter, the patient develops violet or yellow blisters, brown plaques, or shallow ulcers on the toes, which often burn, itch, or become painful. These lesions typically disappear when the weather warms up at the beginning of spring. However, in some chronic cases in which the lesions do not disappear in warm weather, or in which the lesions cause severe pigmentation and disfiguration of the lower part of the leg, the diagnosis may be more difficult.

The main obstacle to establishing the diagnosis of pernio is unfamiliarity of the healthcare provider with the disease. Since many of the dermatological manifestations associated with pernio overlap with other serious diseases, it is not uncommon for pernio patients to be subjected to unnecessary investigations and suffer needless delay in proper treatment.5,47,51 Characteristically, peripheral pulses and peripheral blood pressure measurements are normal unless the patient has underlying peripheral artery disease (PAD) or the pernio has been of such long duration that chronic occlusive vascular disease has developed.6 Pulse volume recordings (PVR) and segmental blood pressures may be abnormal in patients with pernio. This may be due to either vasospasm (the study will normalize with warming of the extremity) or fixed vascular disease due to long-standing pernio.52

Because the diagnosis of pernio is a clinical diagnosis, sophisticated laboratory tests are often not needed, but it is important to rule out other entities that can mimic pernio. The following tests may be obtained: complete blood cell count (CBC) with differential, ANA titer, rheumatoid factor (RF), comprehensive metabolic panel, cryoglobulin, cryofibrinogen, cold agglutinin, and serum viscosity measurements. Arteriography and skin biopsy are not warranted to establish the diagnosis of pernio, except in the occasional case where a clear history could not be obtained or a concomitant vascular pathology (e.g., atheromatous embolization) is suspected.

The differential diagnosis of pernio includes a variety of diseases. Atheromatous emboli (blue toe syndrome) is the most challenging diagnostic entity to differentiate from pernio because similar lesions may be present in each disorder (see Chapter 47).53 When the history of cold exposure is uncertain and in patients with established or suspected atherosclerosis, imaging studies often are warranted to demonstrate atheroma in the aorta or iliac vessels. A biopsy of these lesions showing characteristic cholesterol clefts establishes the diagnosis of atheromatous emboli.53

The next group of diseases that may be confused with pernio include those with chronic recurrent erythematous, nodular, and ulcerative lesions: erythema induratum, nodular vasculitis, erythema nodosum, and cold panniculitis. Erythema induratum (Bazin’s disease) is often but not always a cutaneous form of tuberculosis that affects adolescent girls and is manifested by nodular ulcerating lesions of the calves.7,54 Nontuberculous forms of recurrent painful nodules are called nodular vasculitis.54 Women over the age of 30 years are usually affected, and no apparent cause is known. Although the nodules of nodular vasculitis are extremely painful, they rarely ulcerate. Erythema nodosum may be differentiated from pernio in that it may be associated with fever, arthralgias, malaise, and an underlying disease. The lesions are painful and generally do not ulcerate. Cold panniculitis is another important entity characterized by painful nodules that appear on the skin after cold exposure and can be reproduced by application of an ice cube. The histology of these lesions reveals fat necrosis.55 The palpable purpuric lesion sometimes present in pernio must be differentiated from other types of vasculitis, especially leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Lack of the systemic manifestations and laboratory abnormalities that occur in leukocytoclastic vasculitis and the relation of the lesions to cold exposure in pernio serve to separate these two conditions. Rarely, a skin biopsy may be needed to make a definitive diagnosis.

Treatment

Since the primary trigger for development of pernio is cold exposure, prevention is the mainstay of management. Working in a damp cold basement or living in a poorly heated apartment may necessitate change of profession or moving to a properly heated residence. Patients do not always volunteer information about the climate of their residence and workplace, so the physician may need to ask specifically about the quality of heating systems and the degree of humidity present. The patient should be instructed on methods of proper dress. Adequate body insulation with gloves, stockings, footwear, and headwear may be needed. As is the case in the treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon, the entire body must be kept warm.

A dihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, such as nifedipine, is quite effective in patients with pernio. In a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized crossover pilot study, Dowd et al. reported that treatment with 20 mg of nifedipine three times daily, when given shortly after the appearance of lesions, led to resolution of the lesions within 7 to 10 days, compared to 20 to 28 days with placebo. In addition, the pain disappeared within 5 days in the treated group, compared to 20 to 25 days in the group receiving placebo.56 In a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized trial, Rustin et al. have shown that nifedipine given at a daily dose of 20 to 60 mg was shown to reduce severity of symptoms, shorten their duration, enhance resolution of existing lesions, and prevent development of new lesions.57 Based upon these studies and the authors’ experience, all patients are prescribed either nifedipine or amlodipine to facilitate healing of the lesions and prevent their recurrence. Others have had success with α-blocking agents such as prazocin.52 When spring and summer approach, the medications can be discontinued and then restarted the following fall. These pharmacological therapies should be used in conjunction with other preventive strategies already discussed.

A recent study reported improvement in symptoms in four of five patients treated with hydroxychloraquin.58 However, it should be noted that all four of the patients showing improvement had an underlying connective tissue disease (Sjögren’s syndrome [1], SLE [2], or a family history of connective tissue disease [1]).

Despite speculation that it may enhance resolution of active lesions and provide subjective improvement, sympathectomy does not prevent recurrence of new lesions and has little effect if any on pigmentation and thickness at the sites of perniotic lesions. Conflicting reports exist about use of other treatment modalities such as topical vasodilators, topical or systemic corticosteroids, calcium, vitamin D, and intramuscular (IM) vitamin K. Given the controversy and lack of prospective studies, routine use of these agents is not recommended.8,19

1 McGovern T., Wright I.S., Kruger E. Pernio: a vascular disease. Am Heart J. 1941;22:583.

2 Bazin E. Lecons theoriques et cliniques sur la scrofule. Paris, 1861.

3 Corlett W.T. Cold as an etiological factor in diseases of the skin. 1894.

4 Winner A., Cooper-Willis E. Chilblains in service women. Lancet. 1946;1:663.

5 Goette D.K. Chilblains (perniosis). J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:257–262.

6 Jacob J.R., Weisman M.H., Rosenblatt S.I., et al. Chronic pernio. A historical perspective of cold-induced vascular disease. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:1589–1592.

7 Lynn R.B. Chilblains. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1954;99:720.

8 Olin J.W., Arrabi W. Vascular diseases related to extremes in environmental temperature. In: Young J.R., Olin J.W., Bartholomew J.R. Peripheral vascular disease. ed 2. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book, Inc; 1996:611–613.

9 Purdue G.F., Hunt J.L. Cold injury: a collective review. J Burn Care Rehabil. 1986;7:417–421.

10 Wessagowit P., Asawanonda P., Noppakun N. Papular perniosis mimicking erythema multiforme: the first case report in Thailand. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:527–529.

11 Weston W.L., Morelli J.G. Childhood pernio and cryoproteins. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000;17:97–99.

12 Chan Y., Tang W.Y., Lam W.Y., et al. A cluster of chilblains in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2008;14:185–191.

13 DeGroot D.W., Castellani J.W., Williams J.O., et al. Epidemiology of U.S. Army cold weather injuries, 1980-1999. Aviat Space Environ Med. 2003;74:564–570.

14 Eubanks R.G. Heat and cold injuries. J Ark Med Soc. 1974;71:53–58.

15 Kulka J.P. Vasomotor microcirculatory insufficiency: observations on nonfreezing cold injury of the mouse ear. Angiology. 1961;12:491–506.

16 Lewis T. Observations upon the reactions of the vessels of the human skin to cold. Heart. 1930;15:177–208.

17 Goodfield M. Cold-induced skin disorders. Practitioner. 1989;233:1616–1620.

18 Price R.D., Murdoch D.R. Perniosis (chilblains) of the thigh: report of five cases, including four following river crossings. High Alt Med Biol. 2001;2:535–538.

19 Almahameed A., Pinto D.S. Pernio (chilblains). Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2008;10:128–135.

20 Lewis S.T. Observations on some normal and injurious effects of cold upon the skin and underlying tissues: chilblains and allied conditions. BMJ. 1941;2:837.

21 Viguier M., Pinquier L., Cavelier-Balloy B., et al. Clinical and histopathologic features and immunologic variables in patients with severe chilblains. A study of the relationship to lupus erythematosus. Medicine (Baltimore). 2001;80:180–188.

22 Yang X., Perez O.A., English J.C.III. Adult perniosis and cryoglobulinemia: a retrospective study and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:e21–e22.

23 Baker H. Chronic monocytic leukemia with necrosis of pinnae. Br J Dermatol. 1946;76:480–481.

24 Kelly J.W., Dowling J.P. Pernio. A possible association with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:1048–1052.

25 Marks R., Lim C.C., Borrie P.F. A perniotic syndrome with monocytosis and neutropenia; a possible association with a preleukaemic state. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:327–332.

26 Stagaki E., Mountford W.K., Lackland D.T., et al. The treatment of lupus pernio: results of 116 treatment courses in 54 patients. Chest. 2009;135:468–476.

27 Cribier B., Djeridi N., Peltre B., et al. A histologic and immunohistochemical study of chilblains. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:924–929.

28 Herman E.W., Kezis J.S., Silvers D.N. A distinctive variant of pernio. Clinical and histopathologic study of nine cases. Arch Dermatol. 1981;117:26–28.

29 Wall L.M., Smith N.P. Perniosis: a histopathological review. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1981;6:263–271.

30 Corbett D., Benson P. Military dermatology. In: Zajtchuk R., Bellamy R.F. Textbook of military medicine. Part III. Diseases of the environment. Washington, DC: Office of the Surgeon General, 1994.

31 Inoue G., Miura T. Microgeodic disease affecting the hands and feet of children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1991;11:59–63.

32 Page E.H., Shear N.H. Temperature-dependent skin disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:1003–1019.

33 Boada A., Bielsa I., Fernandez-Figueras M.T., et al. Perniosis: clinical and histopathological analysis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32:19–23.

34 Gourlay R.J. The problem of chilblains: with a note of their treatment with nicotinic acid. BMJ. 1948;1:336–339.

35 Parra S.L., Wisco O.J. What is your diagnosis? Perniosis (chilblain). Cutis. 2009;84:15. 27–15, 29

36 Prakash S., Weisman M.H. Idiopathic chilblains. Am J Med. 2009;122:1152–1155.

37 McCleskey P.E., Winter K.J., Devillez R.L. Tender papules on the hands. Idiopathic chilblains (perniosis). Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1501–1506.

38 Simon T.D., Soep J.B., Hollister J.R. Pernio in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2005;116:e472–e475.

39 Winter kibes in horsey women. Lancet. 1980;2:1345.

40 Beacham B.E., Cooper P.H., Buchanan C.S., et al. Equestrian cold panniculitis in women. Arch Dermatol. 1980;116:1025–1027.

41 De Silva B.D., McLaren K., Doherty V.R. Equestrian perniosis associated with cold agglutinins: a novel finding. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:285–288.

42 Duffill M.B. Milkers’ chilblains. N Z Med J. 1993;106:101–103.

43 Fisher D.A., Everett M.A. Violaceous rash of dorsal fingers in a woman. Diagnosis: chilblain lupus erythematosus (perniosis). Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:459. 462

44 Thomas E.W. Chapping and chilblains. Practitioner. 1964;193:755–760.

45 Weismann K., Larsen F.G. Pernio of the hips in young girls wearing tight-fitting jeans with a low waistband. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:558–559.

46 Walsh S. More red toes. J Pediatr Health Care. 2000;14:193. 205–193, 206

47 Giusti R., Tunnessen W.W.Jr. Picture of the month. Chilblains (pernio). Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:1055–1056.

48 Gardinal-Galera I., Pajot C., Paul C., et al. Childhood chilblains is an uncommon and invalidant disease. Arch Dis Child. 2010;95:567–568.

49 The American HeritageR Dictionary for the English Language. 2000.

50 Millard L.G., Rowell N.R. Chilblain lupus erythematosus (Hutchinson). A clinical and laboratory study of 17 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1978;98:497–506.

51 Parlette E.C., Parlette H.L.III. Erythrocyanotic discoloration of the toes. Cutis. 2000;65:223–224. 226

52 Spittell J.A.Jr, Spittell P.C. Chronic pernio: another cause of blue toes. Int Angiol. 1992;11:46–50.

53 Olin J.W., Bartholomew J.R. Atheromatous embolization syndrome. In: Cronenwett J.L., Johnston K.W. Rutherford’s vascular surgery. ed 7. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co; 2010:2422–2434.

54 Montgomery H., O’Leary P.A., Barker N.W. Nodular vascular disease of the legs. JAMA. 1945;128:335.

55 Solomon L.M., Beerman H. Cold panniculitis. Arch Dermatol. 1961;88:897.

56 Dowd P.M., Rustin M.H., Lanigan S. Nifedipine in the treatment of chilblains. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293:923–924.

57 Rustin M.H., Newton J.A., Smith N.P., et al. The treatment of chilblains with nifedipine: the results of a pilot study, a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized study and a long-term open trial. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:267–275.

58 Yang X., Perez O.A., English J.C.III. Successful treatment of perniosis with hydroxychloroquine. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9:1242–1246.