25 SUSPECTED METASTATIC DISEASE

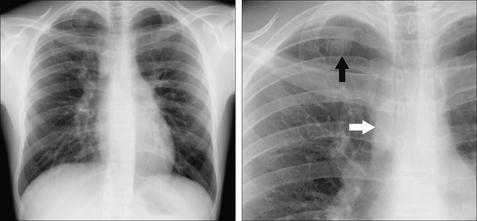

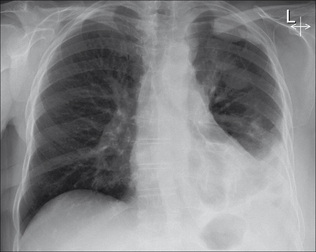

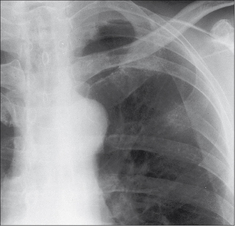

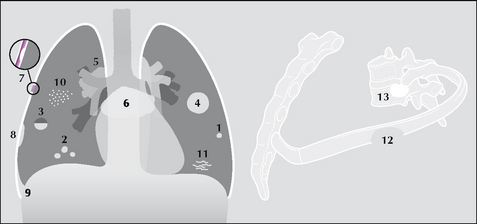

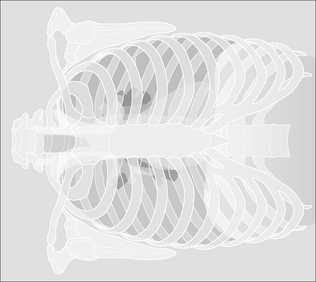

This chapter concentrates on metastases arising from extrathoracic primary neoplasms (i.e. excluding bronchial carcinoma). Many patients with an extrathoracic primary tumour will undergo CXR examination in order to check for metastases. When this CXR examination is requested it is important to know: (a) which tumours are most likely to produce lung, hilar, mediastinal, lymphangitic, pleural or bone deposits; and (b) the various radiographic features of metastatic disease (Fig. 25.1).

Figure 25.1 Thoracic metastases: (1) and (2) solitary or multiple; (3) cavitating;(4) cannonball; (5) hilar lymphadenopathy; (6) subcarinal/mediastinal lymphadenopathy;(7) pleural; (8) subpleural; (9) pleural effusion secondary to pleural deposit(s);(10) miliary (resembling millet seeds); (11) lymphangitis carcinomatosa; (12) lytic;(13) sclerotic.

SPREADING AND SEEDING

The precise mechanisms determining whether malignant cells enter the lymphatic or venous circulation and subsequently spread to and implant in the thorax are imperfectly understood1-6. Tumour affinity for a particular thoracic tissue (lung, pleura, bone, bronchial endothelium) varies between malignancies. How some malignancies reach and settle in the thorax is shown in Table 25.1. The various pathways give an inkling as to why some primary tumours metastasise to the thorax more commonly than do others.

Table 25.1 Tumour routes to the thorax1,7–9.

| Channel | Malignancy | Pathway |

|---|---|---|

| Lymphatic | Breast/stomach/pancreas/larynx/cervix | Draining lymphatics → lymph nodes → thoracic duct → vena cava → right atrium → pulmonary arteries → lungs |

| Venous (1) | Renal/thyroid/testicular/sarcomas/melanoma/head and neck | Draining veins → vena cava → right atrium → pulmonary arteries → lungs |

| Venous (2) | Colon/stomach/pancreas | Draining veins → portal vein → liver → hepatic veins → lungs |

| Venous (3) | Colon/stomach/pancreas | Batson’s venous plexus (see below) → bones7,8 |

| Dual venous (4) | Renal | |

| Multiple | Breast1,6,9 |

In 1940 Oscar V. Batson described the vertebral venous system7,8. The term Batson’s venous plexus refers to the valveless plexiform vertebral veins that communicate freely with the superior and inferior vena cavae. This venous system, or plexus, is an important pathway for tumour spread to bone, and also to the brain and lungs.

SEARCHING FOR LUNG METASTASES1,2,9,10

GENERAL

THE PRIMARY TUMOUR AND THE CXR

Malignancies that commonly metastasise to the lungs: sarcomas, renal cell carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, testicular cancer, some functioning thyroid carcinomas.

Malignancies that commonly metastasise to the lungs: sarcomas, renal cell carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, testicular cancer, some functioning thyroid carcinomas. Lung metastases are often present at the time of the initial diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, osteogenic sarcoma or Wilms’ tumour.

Lung metastases are often present at the time of the initial diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, osteogenic sarcoma or Wilms’ tumour.Table 25.2 Lung metastases1–3,9–12.

| CXR finding | Most common tumours | Other tumours |

|---|---|---|

| Kidney, head/neck, uterus, prostate, breast, colon | Choriocarcinoma, testicle, melanoma, thyroid, osteogenic sarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, Wilms’ tumour, rhabdomyosarcoma | |

| Colon | Melanoma, sarcoma, breast, kidney, bladder, testicle | |

| Colon, rectum, kidney, melanoma, sarcomas | ||

| Cervix in females, head and neck tumours in males, sarcomas | Colon | |

| Thyroid, kidney | Osteogenic sarcoma, melanoma, choriocarcinoma | |

| Osteogenic sarcomas | Chondrosarcoma, thyroid, colon, pancreas | |

| Choriocarcinoma… occasionally2 |

SEARCHING FOR HILAR AND MEDIASTINAL METASTASES

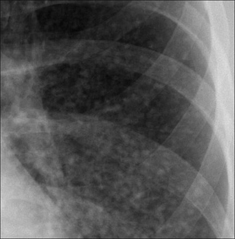

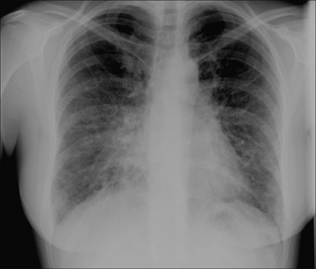

LYMPHANGITIS CARCINOMATOSA1,2

Tumour involvement of the lymphatics of the lung results from haematogenous spread. The CXR appearance is that of interstitial disease—i.e. reticular or reticulo-nodular shadowing. Initially, this may be indistinguishable from other interstitial processes such as pulmonary oedema. The most common primary is breast carcinoma.

Lymphangitic spread is usually bilateral, infrequently unilateral. Sometimes it is associated with a pleural effusion and/or enlarged hilar nodes.

Lymphangitic spread is usually bilateral, infrequently unilateral. Sometimes it is associated with a pleural effusion and/or enlarged hilar nodes. Very occasionally a patient with a known primary carcinoma may develop dyspnoea due to lymphangitic deposits and the CXR may appear clear1.

Very occasionally a patient with a known primary carcinoma may develop dyspnoea due to lymphangitic deposits and the CXR may appear clear1.SEARCHING FOR PLEURAL METASTASES14

SEARCHING FOR BONE METASTASES3,8,9,15

Some primary tumours have a propensity for metastasising to bone (Table 25.3). Other tumours rarely do so.

Some primary tumours have a propensity for metastasising to bone (Table 25.3). Other tumours rarely do so. Bone metastases occur as a result of either: (a) tumour cells entering the venous system and being deposited in bone via arteries and capillaries;(b) retrograde venous flow (e.g. prostatic carcinoma); (c) dissemination via Batson’s venous plexus; or (d) direct invasion of adjacent bone.

Bone metastases occur as a result of either: (a) tumour cells entering the venous system and being deposited in bone via arteries and capillaries;(b) retrograde venous flow (e.g. prostatic carcinoma); (c) dissemination via Batson’s venous plexus; or (d) direct invasion of adjacent bone. Bone deposits are usually either solely lytic (i.e. lucent) or solely sclerotic (i.e. dense)—see Table 25.3. Very occasionally a primary carcinoma may produce both lytic and sclerotic deposits in an individual patient.

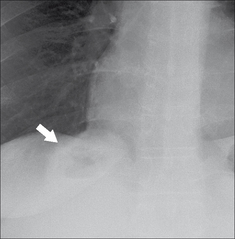

Bone deposits are usually either solely lytic (i.e. lucent) or solely sclerotic (i.e. dense)—see Table 25.3. Very occasionally a primary carcinoma may produce both lytic and sclerotic deposits in an individual patient. A helpful trick. Any patient with bone or chest wall pain. When checking the ribs:

A helpful trick. Any patient with bone or chest wall pain. When checking the ribs:

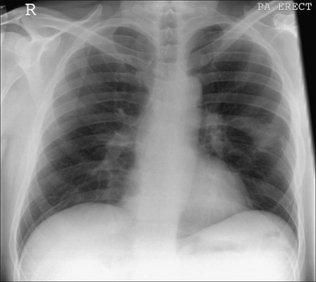

Rotate the image so that the long axis of the CXR is parallel to the floor—assess the ribs again (Fig. 25.8).

Rotate the image so that the long axis of the CXR is parallel to the floor—assess the ribs again (Fig. 25.8).Table 25.3 Bone metastases15.

| Appearance | Most common primary | Less common primary |

|---|---|---|

| Sclerotic | ||

| Lytic | Prostate, melanoma, neuroblastoma | |

| Lytic…sometimes causing expansion of the affected bone | Renal, thyroid |

Figure 25.8 Checking the ribs for metastases. Examining the ribs with the CXR aligned horizontally. This trick makes the ribs stand out. Note the destructive lesion in the posterior aspect of the left fifth rib. If you don’t think that the lesion is shown particularly clearly— turn this page through 90° so that you are looking at the bones with the CXR upside down. Now what do you think?

AN UNEXPECTED RIB FRACTURE—IS IT PATHOLOGICAL?15-17

Most pathological fractures are due to a metastasis or to myeloma. Whenever a clinically unsuspected rib fracture is detected on a CXR:

1. Coppage L, Shaw C, Curtis AM. Metastatic disease to the chest in patients with extrathoracic malignancy. J Thorac Imaging. 1987;2:24-37.

2. Libshitz HI, North LB. Pulmonary metastases. Radiol Clin North Am. 1982;20:437-451.

3. Collins J, Stern EJ. Chest Radiology: The Essentials. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 1999.

4. Janower ML, Blennerhassett JB. Lymphangitic spread of metastatic cancer to the lung. A radiologic–pathologic classification. Radiology. 1971;101:267-273.

5. McCloud TC, Kalisher L, Stark P, et al. Intrathoracic lymph node metastases from extrathoracic neoplasms. AJR. 1978;131:403-407.

6. Viadana E, Bross ID, Pickren JW. Cascade spread of blood borne metastases in solid and non-solid cancers in humans. In: Weiss L, Gilbert HA, editors. Pulmonary Metastases. Boston MA: GK Hall; 1978:143-167.

7. Batson OV. Function of vertebral veins and their role in spread of metastases. Ann Surg. 1940;112:138-149.

8. Batson OV. The vertebral vein system. AJR. 1957;78:195-212.

9. Seo JB, Im JG, Goo JM, et al. Atypical pulmonary metastases: spectrum of radiologic findings. Radiographics. 2001;21:403-417.

10. Crow J, Slavin G, Kreel L. Pulmonary metastasis: A pathologic and radiologic study. Cancer. 1981;47:2595-2602.

11. Latour A, Shulman HS. Thoracic manifestations of renal cell carcinoma. Radiology. 1976;121:43-48.

12. Libshitz HI, Baber CE, Hammond CB. The pulmonary metastases of choriocarcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1977;49:412-416.

13. Maile CW, Rodan BA, Godwin JD, et al. Calcification in pulmonary metastases. Br J Radiol. 1982;55:108-113.

14. Raju RN, Kardinal CG. Pleural effusion in breast carcinoma: analysis of 122 cases. Cancer. 1981;48:2524-2527.

15. Pagani JJ, Libshitz HI. Imaging bone metastases. Radiol Clin North Am. 1982;20:545-560.

16. Grover SB, Dhar A. Imaging spectrum in sclerotic myelomas: an experience of three cases. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1828-1831.

17. Clayer MT. Lytic bone lesions in an Australian population: the results of 100 consecutive biopsies. ANZ J Surj. 2006;76:732-735.