Chapter 19 Psychologic Treatment of Children and Adolescents

Barriers that prevent children and their families from obtaining needed mental health services include stigma, shortages of mental health professionals, inadequate coverage of mental health services in public and private health insurance programs, inadequately trained clinicians, and fragmented service delivery systems. Pediatric practitioners are gatekeepers to children’s mental health services and increasingly are the primary providers of these services when specialized mental health care is not available.

The provision of supportive counseling, anticipatory guidance, and parent psychoeducation (Chapter 5) combined with medication management of noncomplex attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and pervasive developmental disorders are commonly undertaken in the medical home. Youngsters with complex and co-occurring psychiatric illnesses require intervention from specially trained mental health clinicians.

Bibliography

American Academy of Pediatrics: Strategies for system change in children’s mental health: a chapter action toolkit, Chicago, 2007, American Academy of Pediatrics.

19.1 Psychopharmacology

Safety and efficacy data are available for the use of single psychotropic medications for the treatment of a number of childhood psychiatric disorders, including depressive, obsessive-compulsive, attention-deficit/hyperactivity, anxiety (including separation anxiety, social phobia, generalized anxiety), bipolar, and tic disorders. There also is evidence supporting the use of psychotropic medications for aggression and serious problems with impulse control in disruptive behavior and pervasive developmental disorders.

The evidence for treatment using multiple psychotropic medications at the same time is much smaller. Combinations of medications are used to address complex comorbid conditions, manage side effects, increase treatment response, and/or address symptoms hypothesized to be associated with multiple underlying neurotransmitter abnormalities (e.g., dopamine agonists for hyperactivity and serotonin agonists for anxiety).

To ensure safe and appropriate use of psychotropic medications, prescribers should follow best practice principles that underlie medication prescribing (Table 19-1). The use of medication involves a series of interconnected steps including performing an assessment, deciding on treatment and a monitoring plan, obtaining treatment assent or consent, and implementing treatment. Cognitive, emotional, and/or behavior symptoms are targets for medication intervention when there is no response to available evidence-based psychosocial interventions, there is a significant risk of harm, and/or there is significant functional impairment. Commonly encountered target symptom domains include agitation, anxiety, depression, hyperactivity, inattention, impulsivity, mania, and psychosis (Table 19-2).

Table 19-1 CLINICAL APPROACH TO PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGIC TREATMENT

Modified from Myers SM, Johnson CP, American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children with Disabilities: Management of children with autism spectrum disorders, Pediatrics 120:1162–1182, 2007.

Table 19-2 TARGET SYMPTOM APPROACH TO PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGIC MANAGEMENT

| TARGET SYMPTOM | MEDICATION CONSIDERATIONS |

|---|---|

| Agitation | |

| Anxiety | |

| Depression | Antidepressant |

| Hyperactivity, inattention, impulsivity | Atomoxetine, bupropion, stimulant |

| Mania | |

| Psychosis | Atypical antipsychotic |

Modified from Shaw RJ, DeMaso DR: Clinical manual of pediatric psychosomatic medicine: mental health consultation with physically ill children and adolescents, Washington, DC, 2006, American Psychiatric Press, p 306.

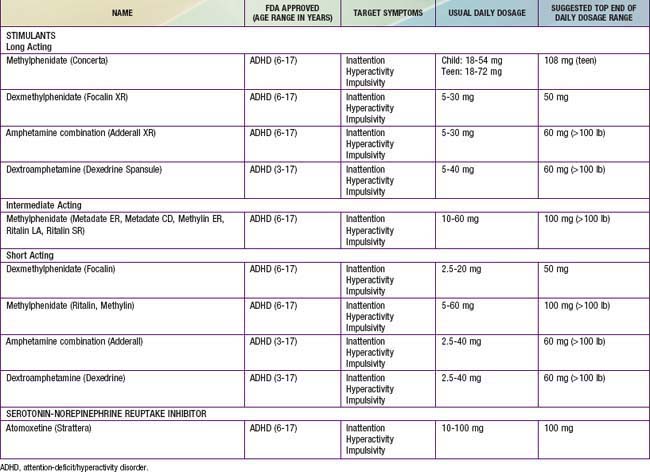

Stimulants

Stimulants are sympathomimetic drugs that act both in the central nervous system and peripherally by enhancing dopaminergic and noradrenergic transmission (Table 19-3). These medications are used to treat ADHD (Chapter 30) and in some cases as an adjunct in the treatment of depression and for fatigue or malaise associated with chronic physical illnesses. There is a range of stimulant options including those with short half-lives (typically 4 hr) and those with long half-lives (8-12 hr). The most commonly reported side effects are appetite suppression and sleep disturbances. Irritability, headaches, stomachaches, lethargy, hallucinations, and fatigue have also been reported. Anorexia and weight loss have been noted with controversy about their impact on ultimate growth in height.

Sudden death has been reported in association with the use of stimulants in children with structural cardiac abnormalities. This has led to the recommendation to avoid stimulants in patients with these abnormalities. Currently, no routine pretreatment cardiology evaluation is indicated unless the patient has a cardiac disorder and/or symptoms.

Atomoxetine is a selective inhibitor of presynaptic norepinephrine transporters; it increases dopamine and norepinephrine in the prefrontal cortex. It is effective in treating ADHD for 24 hr despite a plasma half-life of 4 hr. Common side effects include sedation, fatigue, somnolence, decreased appetite, weight loss, nausea, upset stomach, abdominal pain, and dizziness along with nonclinical increases in heart rate and blood pressure. In ADHD treatment studies, atomoxetine has had effect sizes of 0.6 to 0.7, compared to the 0.9 effect size with stimulants.

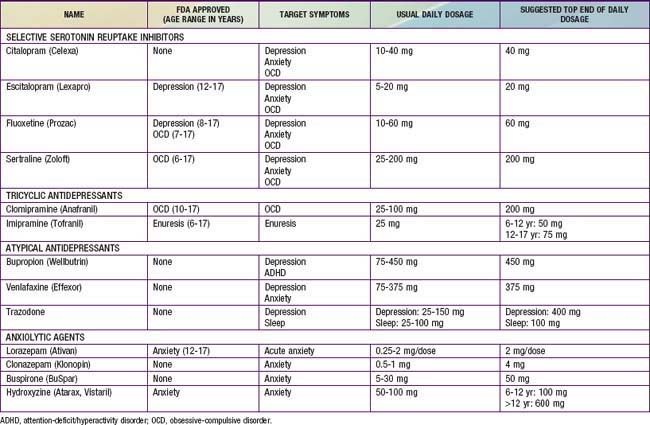

Antidepressants

Antidepressant drugs act on pre- and postsynaptic receptors affecting the release and reuptake of brain neurotransmitters, including norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine (Table 19-4). These medications have been useful in the treatment of depressive, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorders.

The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the first line of medication treatment for anxiety and depressive disorders; the evidence supports a higher degree of efficacy for anxiety compared to depression. They have a large margin of safety with no cardiovascular effects. Side effects include irritability, insomnia, appetite changes, gastrointestinal symptoms, headaches, diaphoresis, restlessness, and sexual dysfunction (Chapter 58). Withdrawal symptoms are more common in short-acting SSRIs. Behavioral activation and suicidal thoughts have been reported. This has led to recommendations for close monitoring for these adverse effects, especially in the 1st wks of treatment.

The tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) have mixed mechanisms of action (e.g., clomipramine is primarily serotonergic; imipramine is both noradrenergic and serotoninergic). With the advent of the SSRIs, the lack of efficacy studies (particularly in depression), and more serious side effects, the use of TCAs in children has declined. They continue to be used in the treatment of some anxiety disorders (particularly obsessive-compulsive disorder) and, unlike the SSRIs, can be helpful in pain disorders. They have a narrow therapeutic index, with overdoses being potentially fatal (Chapter 58). Anticholinergic symptoms (e.g., dry mouth, blurred vision, and constipation) are the most common side effects. TCAs can have cardiac conduction effects in doses higher than 3.5 mg/kg. Blood pressure and electrocardiographic monitoring is indicated at doses above this level.

The atypical antidepressants include bupropion, venlafaxine, and trazodone (see Table 19-4); they are second-line medications for anxiety and depressive disorders. Bupropion has also been used for smoking cessation and ADHD. Bupropion appears to have an indirect mixed agonist effect on dopamine and norepinephrine transmission. Common side effects include irritability, nausea, anorexia, headache, and insomnia. Venlafaxine has both serotonergic and noradrenergic properties. Side effects are similar to SSRIs, including irritability, insomnia, headaches, anorexia, nervousness, dizziness, and blood pressure changes. Trazodone also has a mixed mechanism of action, with serotonergic and anti-α-adrenergic properties. Sedation is its most common side effect, leading to its common use for insomnia.

Anxiolytic agents (including lorazepam, clonazepam, buspirone, and hydroxyzine) have all been effectively used for acute situational anxiety (see Table 19-4). Their efficacy as chronic medication is poorer, particularly when used as a monotherapy agent.

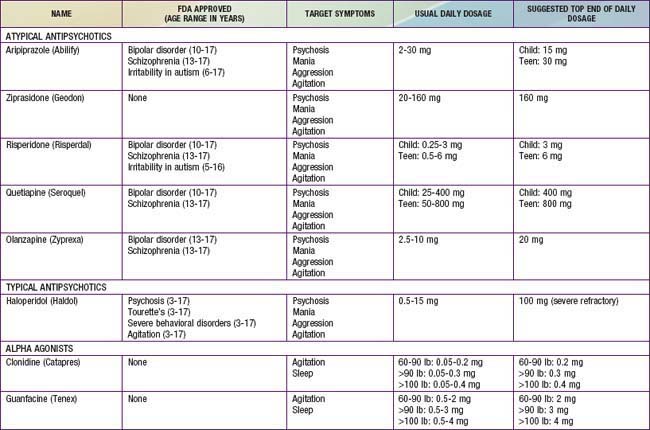

Antipsychotics

Based on their mechanism of action, antipsychotic medication can be divided into typical (blocking dopamine D2 receptor) and atypical (mixed dopaminergic and serotoninergic (5-HT2) activity) agents (Table 19-5).

The atypical antipsychotics have relatively strong antagonistic interactions with 5-HT2 receptors and perhaps more variable activity at central adrenergic, cholinergic, and histaminic sites, which might account for varying side effects noted among these agents. These medications have an evidence base for the treatment of psychotic disorders, moderate to severe agitation, and increasingly for monotherapy in bipolar disorder. Risperidone and aripiprazole are two of the most commonly used medications in this class.

The atypical antipsychotics have significant side effects including extrapyramidal symptoms (e.g., restlessness and dyskinesias), weight gain, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, hyperprolactinemia, hematologic adverse effects (e.g., leukopenia or neutropenia), seizures, hepatotoxicity, neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and cardiovascular effects. For all atypical antipsychotics, body mass index, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, fasting lipid profiles, and abnormal movements should be closely monitored. If there is a family or personal history suggestive of cardiac disease, electrocardiograms should also be monitored.

Haloperidol is a high-potency butyrophenone that is the typical antipsychotic most commonly used. This medication is useful in psychosis, Tourette’s disorder, and severe agitation. Side effects include anticholinergic effects, weight gain, drowsiness, and extrapyramidal symptoms (dystonia, rigidity, tremor, and akathisia). There is a risk of tardive dyskinesia with chronic administration.

α-Adrenergic Agents

The α-adrenergic agents (clonidine and guanfacine) are presynaptic adrenergic agonists that appear to stimulate inhibitory presynaptic autoreceptors in the central nervous system. Although most commonly used in Tourette’s disorder and ADHD, these agents may be useful in controlling aggression, particularly in patients with developmental disorders (see Table 19-5). Sedation, hypotension, dry mouth, depression, and confusion are potential side effects. Abrupt withdrawal can result in rebound hypertension. Guanfacine appears to be less sedating and to have a longer duration of action than clonidine.

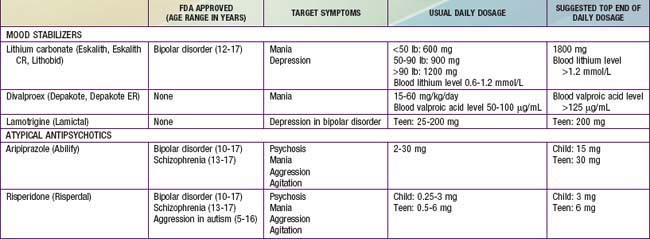

Mood Stabilizers

Several medications have been shown to be potentially helpful in children experiencing significant mood instability and/or mania, although the evidence base is sparse (Table 19-6).

Lithium’s mechanism of action is not well understood, though proposed theories relate to neurotransmission, endocrine effects, circadian rhythm, and cellular processes. Common side effects include polyuria and polydipsia and central nervous system symptoms (tremor, somnolence, and memory impairment). Periodic monitoring of lithium levels along with thyroid and renal function is needed. Lithium serum levels of 0.8-1.2 mEq/L are targeted for acute episodes and 0.6-0.9 mEq/L are targeted for maintenance therapy.

Valproic acid is an anticonvulsant with some evidence supporting its use in the treatment of mania. The therapeutic plasma concentration range is 50-100 µg/mL. Common side effects include sedation, gastrointestinal symptoms, and hair thinning. Idiosyncratic bone marrow suppression and liver toxicity have been reported, necessitating monitoring of blood counts as well as liver and kidney function. Lamotrigine is another anticonvulsant that may be useful in the treatment of adolescent bipolar depression. It has been associated with potentially life-threatening Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Medication Use in Physical Illness

There are special considerations in the use of psychotropic medications with physically ill children. Between 80% and 95% of psychotropic medications are protein bound, with the exceptions being lithium (0%), methylphenidate (10-30%), venlafaxine (25-30%), gabapentin (0-3%), and topiramate (9-17%). As a result, psychotropic levels may be directly affected because albumin binding is reduced in many physical illnesses. Metabolism is primarily through the liver and gastrointestinal tract, with excretion via the kidney. Therefore, dosages may need to be adjusted in children with hepatic or renal impairment.

Hepatic Disease

It is often necessary to use lower doses of medications in patients with hepatic disease. Initial dosing of medications should be reduced and titration should proceed slowly. In steady-state situations, changes in protein binding can result in elevated unbound medication, resulting in increased drug action even in the presence of normal serum drug concentrations. Because it is often difficult to predict changes in protein binding, it is important to maintain attention to the clinical effects of psychotropic medications and not rely exclusively on serum drug concentrations.

In acute hepatitis, there is generally no need to modify dosing because metabolism is only minimally altered. In chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis, hepatocytes are destroyed and doses might need to be modified.

Medications with high baseline rates of liver clearance (e.g., haloperidol, sertraline, venlafaxine, and TCAs) are significantly affected by hepatic disease. For drugs that have significant hepatic metabolism, intravenous administration may be preferred because parenteral administration avoids first-pass liver metabolic effects and the dosing and action of parenteral medications are similar to those in patients with normal hepatic function. Valproic acid can impair the metabolism of the hepatocyte disproportionate to the degree of hepatocellular damage. In patients with valproate-induced liver injury, low albumin, high prothrombin, and high ammonia may be seen without significant elevation in liver transaminases.

Gastrointestinal Disease

Medications with anticholinergic side effects can slow gastrointestinal motility, affecting absorption and causing constipation. SSRIs increase gastric motility and can cause diarrhea. SSRIs have a potential to increase the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, especially when they are co-administered with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Extended-release or controlled-release preparations of medications can reduce gastrointestinal side effects, particularly where gastric distress is related to rapid increases in plasma drug concentrations.

Kidney Disease

With the exceptions of lithium and gabapentin, psychotropic medications do not generally require significant dosing adjustments in kidney failure. It is important to monitor serum concentrations in renal insufficiency, particularly for medications with a narrow therapeutic index; cyclosporine can elevate serum lithium levels by decreasing lithium excretion. Patients with kidney failure and those on dialysis appear to be more sensitive to TCA side effects, possibly because of the accumulation of hydroxylated tricyclic metabolites.

Because most psychotropic medications are highly protein-bound, they are not significantly cleared by dialysis. Lithium, gabapentin, and topiramate are essentially completely removed by dialysis, and the common practice is to administer these medications after dialysis. Patients on dialysis often have significant fluid shifts and are at risk for dehydration, with neuroleptic malignant syndrome being more likely in these situations.

Heart Disease

Cardiovascular effects of psychotropic medications can include orthostatic hypotension, conduction disturbances, and arrhythmias. Orthostatic hypotension is one of the most common cardiovascular side effects of TCAs. Trazodone can cause orthostatic hypotension and exacerbate myocardial instability; SSRIs and bupropion are preferred as antidepressant agents in patients with heart disease.

There is the potential for increased morbidity and mortality in patients with pre-existing cardiac conduction problems. Some of the calcium channel blocking agents (e.g., verapamil) can slow atrioventricular conduction and can theoretically interact with a TCA. Patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome who have a short PR interval (<0.12 sec) and widened QRS interval associated with paroxysmal tachycardia are at high risk for life-threatening ventricular tachycardia that may be exacerbated by the use of a TCA. Quinidine-like effects of TCAs and the antipsychotic agents can lead to prolongation of the QTc interval, with increased risk of ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation, particularly in patients with structural heart disease. Patients with a baseline QTc interval of >440 msec should be considered at particular risk. The range of normal QTc values in children is 400 msec ± 25-30 msec. A QTc value that exceeds 2 standard deviations (>450-460 msec) is considered too long and may be associated with increased mortality. An increase in the QTc from baseline of >60 msec is also associated with increased mortality.

Respiratory Disease

Anxiolytic agents can increase the risk of respiratory suppression in patients with pulmonary disease. SSRIs and buspirone are good alternative medications for treating anxiety. Consideration should be given to possible airway compromise due to acute laryngospasm when dopamine-blocking agents such as antipsychotic or antiemetic medications are used.

Neurological Disease

Psychotropic medications can be used safely with epilepsy following consideration of potential interactions between the psychotropic medication, the seizure disorder, and the anticonvulsant medication. Any behavioral toxicity of anticonvulsants used either alone or in combination should be considered before proceeding with psychotropic treatment. Simplification of combination anticonvulsant therapy or a change to another agent can result in a reduction of behavioral or emotional symptoms and obviate the need for psychotropic intervention. Clomipramine and bupropion possess significant seizure-inducing properties and should be avoided when the risk of seizures is present.

Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is a rare and potentially fatal reaction that can occur during treatment with antipsychotic agents (Chapter 169). The syndrome generally manifests with fever, muscle rigidity, autonomic instability, and delirium. It is associated with elevated serum creatine phosphokinase levels, a metabolic acidosis, and high end-tidal CO2 excretion. It has been estimated to occur in 0.2-1% of patients treated with dopamine-blocking agents. Malnutrition and dehydration in the context of an organic brain syndrome and simultaneous treatment with lithium and antipsychotic agents can increase the risk. Mortality rates may be as high as 20-30% due to dehydration, aspiration, kidney failure, and respiratory collapse. Differential diagnosis of NMS includes heat stroke, malignant hyperthermia, lethal catatonia, serotonin syndrome, and anticholinergic toxicity

Serotonin Syndrome

Serotonin syndrome is characterized by a triad of mental status changes, autonomic hyperactivity, and neuromuscular abnormalities (Chapter 58). It is the result of an excess agonism of the central and peripheral nervous system serotoninergic receptors and can be caused by a range of drugs including SSRIs, valproate, and lithium. Drug-drug interactions that can cause serotonin syndrome include linezolid (an antibiotic that has MAOI properties) and anti-migraine preparations used with an SSRI, as well as combinations of SSRI, trazodone, buspirone, and venlafaxine. It is generally self-limited and can resolve spontaneously after the serotoninergic agents are discontinued. Severe cases require the control of agitation, autonomic instability, and hyperthermia as well as the administration of 5-HT2A antagonists (e.g., cyproheptadine).

Frazier JA, Bregman HA, Jackson JA. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of early-onset bipolar disorder. In: Geller B, Delbello MP, editors. Treatment of bipolar illness in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press; 2008:69-108.

Green WH. Child and adolescent clinical psychopharmacology, ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

Hamernedd PG, Geller DA. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in pediatric psychopharmacology: a review of the evidence. J Pediatr. 2006;48:58-65.

Myers SM, Johnson CP. American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children with Disabilities: Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1162-1182.

Parikh SV. Antidepressants are not all created equal. Lancet. 2009;373:700-701.

Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:225-235.

Rosenheck RA, Krystal JH, Lew R, et al. Long-acting risperidone and oral antipsychotics in unstable schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:842-850.

Scahill L, Oesterheld JR, Martin A. General principles, specific drug treatments, and clinical practice. In: Martin A, Volkmar FR, editors. Lewis’ child and adolescent psychiatry: a comprehensive textbook. ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:754-788.

Shaw RJ, DeMaso DR. Clinical manual of pediatric psychosomatic medicine: mental health consultation with physically ill children and adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2006.

19.2 Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy in children may also be effective in reducing patient symptomatology. Effect sizes in research studies range from 0.71 to 0.84, which are as large as or larger than the effects of psychiatric medications or medicines for many physical illnesses. Despite benefit, only a minority of patients achieve the same level of functioning as average children, because in community settings the effect size of psychotherapy approaches zero. This poor response might reflect the fact that treatment in real-world community settings involves complex and co-occurring disorders, as opposed to the research or academic setting, where comorbid conditions are often excluded.

A variety of psychotherapeutic approaches exist with varying levels of evidence regarding their effectiveness. The following is a simplified rank ordering of the comparative effectiveness of the different therapeutic approaches: cognitive-behavioral therapy, which is considered to be the first-line treatment for anxiety and mild depressive disorders; family therapy; psychodynamic therapy; supportive therapy; and narrative therapy.

Differences between therapeutic approaches may be less pronounced in practice than in theory. The quality of the therapist-patient alliance consistently has been shown to be the strongest predictor of treatment outcome. A positive therapeutic relationship, expecting change to occur, facing problems assertively, increasing mastery, and attributing change to the participation in the therapy have all been connected to effective therapy.

The use of psychotherapy involves a series of interconnected steps including performing an assessment, deciding upon treatment and a monitoring plan, obtaining treatment assent or consent, and implementing treatment. Cognitive, emotional, and/or behavior symptoms are identified that become the targets for evidence-based psychotherapeutic interventions. Psychotherapists ideally develop a treatment plan by combining known evidence-based practices about specific interventions with their clinical judgment to arrive at a specific intervention plan for the individual patient. It is not unusual for the psychotherapist to use elements from more than one treatment approach, including psychopharmacology.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is based on the theory that antecedent events stimulate thoughts and beliefs that in turn cause emotional consequences. CBT is problem-oriented treatment that seeks to identify and change cognitive distortions (e.g., learned helplessness or irrational fears), identify and avoid distressing situations, and identify and practice distress-reducing behavior. Self-monitoring (e.g., daily thought record), self-instruction (e.g., brief sentences asserting thoughts that are comforting and/or adaptive), and self-reinforcement (rewarding oneself) are internal analogues of the charts, prompts, and rewards that in behavior therapy are supplied by parents and/or significant others.

Family Therapy

The core idea in family therapy is that problems exist in families and not just in individuals. The cause of problems in individuals is thought to lie in patterns of family interaction, with other family members helping to maintain the problem. Family dysfunction can take a variety of forms, including enmeshment, disengagement, and maladaptive communication patterns (e.g., parent-child role reversal). Family therapy techniques involve helping family members communicate more effectively, reframing troublesome behavior, and giving directives to disrupt ingrained dysfunctional patterns. Family interventions that include behavioral therapy components are well-established treatments for ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder.

Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

At the core of psychodynamic psychotherapy lies a dynamic interaction between different parts or aspects of the mind. This approach is based on the belief that much of one’s mental activity occurs outside one’s awareness. The patient is often unaware of internal conflicts because threatening or painful emotions, impulses, and memories are repressed. Behavior is then controlled by what the patient does not know about himself or herself. Therapy objectives are to increase self-understanding, increase acceptance of feelings, shift to mature defense mechanisms, and develop realistic relationships between self and others. This therapy is nondirective to allow the patient’s characteristic patterns to emerge so that self-understanding and a corrective emotional experience can then be fostered by the therapist.

Supportive Psychotherapy

Supportive psychotherapy aims to minimize levels of emotional distress. Treatment is focused on the here and now. The therapist is active and helpful in providing the patient with symptomatic relief by containing anxiety, sadness, and anger. The therapist provides education and encouragement to bolster a patient’s existing coping mechanisms.

Narrative Therapy

Narrative therapy is based on the principle that self-stories organize, interpret, and assign meaning to events in a person’s life. It emphasizes the construction of meaning by allowing patients to tell their personal story or narrative of the problem. Narratives typically center on 5 pervasive themes: identity, cause, time-line, consequences, and cure or control. The therapist helps the patient “make meaning” of his or her stories and correct misperceptions or misattributions. The therapist’s role is to help the patient reframe negative narratives (re-storying) into ones that are more positive and progressive.

Shapiro JP, Friedberg RD, Bardenstein KK. Child and adolescent therapy: science and art. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006.

Shaw RJ, DeMaso DR. Clinical manual of pediatric psychosomatic medicine: mental health consultation with physically ill children and adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2006.

19.3 Psychiatric Hospitalization

Psychiatric hospital programs are meant to address the serious risks and severe impairments caused by the most acute and complex forms of psychiatric disorder that cannot be managed effectively at any other level of care. Their goal is to produce rapid clinical stabilization that allows an expeditious, safe, and appropriate treatment transition to a less-intensive level of mental health care outside of the hospital.

High levels of illness severity combined with significant functional impairment signal a need for hospitalization. Admission criteria must include significant signs and symptoms of active psychiatric disorder(s). Functional admission indicators generally include a significant risk of self-harm and/or harm to others, although in some cases the patient is unable to meet basic self-care or health care needs, jeopardizing well-being. Serious emotional disturbances that prevent participation in family, school, or community life can also rise to a level of global impairment that can only be addressed on an inpatient basis.

Discharge planning begins at the time of admission, when efforts are made to coordinate care with services and resources that are already in place for the child or adolescent in the community. Step-down care might be needed in partial hospital or residential settings if integrated services in a single location remain indicated after sufficient clinical stabilization has occurred in the hospital setting. Transition from the hospital entails active collaboration and communication with pediatric practitioners in the child’s medical home.