Chapter 30 Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common neurobehavioral disorder of childhood, among the most prevalent chronic health conditions affecting school-aged children, and the most extensively studied mental disorder of childhood. ADHD is characterized by inattention, including increased distractibility and difficulty sustaining attention; poor impulse control and decreased self-inhibitory capacity; and motor overactivity and motor restlessness (Table 30-1). Definitions vary in different countries (Table 30-2). Affected children commonly experience academic underachievement, problems with interpersonal relationships with family members and peers, and low self-esteem. ADHD often co-occurs with other emotional, behavioral, language, and learning disorders (Table 30-3).

Table 30-1 DSM-IV DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER

CODE BASED ON TYPE

Reprinted with permission from American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association. Copyright 2000 American Psychiatric Association.

Table 30-2 DIFFERENCES BETWEEN U.S. AND EUROPEAN CRITERIA FOR ADHD OR HKD

| DSM-IV ADHD | ICD-10 HKD |

|---|---|

| SYMPTOMS | |

| Either or both of following: | All of following: |

| PERVASIVENESS | |

| Some impairment from symptoms is present in >1 setting | Criteria are met for >1 setting |

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; HKD, hyperkinetic disorder; ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition.

From Biederman J, Faraone S: Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, Lancet 366:237–248, 2005.

Table 30-3 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ATTENTION-DEFICIT/HYPERACTIVITY DISORDER

PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS

DIAGNOSES ASSOCIATED WITH ADHD BEHAVIORS

MEDICAL AND NEUROLOGIC CONDITIONS

Note: Coexisting conditions with possible ADHD presentation include oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety disorders, conduct disorder, depressive disorders, learning disorders, and language disorders. Presence of one or more of the symptoms of these disorders can fall within the spectrum of normal behavior, whereas a range of these symptoms may be problematic but fall short of meeting the full criteria for the disorder.

From Reiff MI, Stein MT: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder evaluation and diagnosis: a practical approach in office practice, Pediatr Clin North Am 50:1019–1048, 2003. Adapted from Reiff MI: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders. In Bergman AB, editor: 20 Common problems in pediatrics, New York, 2001, McGraw-Hill, p 273.

Etiology

No single factor determines the expression of ADHD; ADHD may be a final common pathway for a variety of complex brain developmental processes. Mothers of children with ADHD are more likely to experience birth complications, such as toxemia, lengthy labor, and complicated delivery. Maternal drug use has also been identified as a risk factor in the development of ADHD. Maternal smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy and prenatal or postnatal exposure to lead are commonly linked to attentional difficulties associated with the development of ADHD. Food colorings and preservatives have inconsistently been associated with hyperactivity in previously hyperactive children.

There is a strong genetic component to ADHD. Genetic studies have primarily implicated 2 candidate genes, the dopamine transporter gene (DAT1) and a particular form of the dopamine 4 receptor gene (DRD4), in the development of ADHD. Additional genes that might contribute to ADHD include DOCK2 associated with a pericentric inversion 46N inv(3)(p14:q21) involved in cytokine regulation, a sodium-hydrogen exchange gene, and DRD5, SLC6A3, DBH, SNAP25, SLC6A4, and HTR1B.

Abnormal brain structures are linked to an increased risk of ADHD; 20% of children with severe traumatic brain injury are reported to have subsequent onset of substantial symptoms of impulsivity and inattention. Children with head or other injury and in whom ADHD is later diagnosed might have impaired balance or impulsive behavior as part of the ADHD, thus predisposing them to injury. Structural (functional) abnormalities have been identified in children with ADHD without pre-existing identifiable brain injury. These include dysregulation of the frontal subcortical circuits, small cortical volumes in this region, widespread small-volume reduction throughout the brain, and abnormalities of the cerebellum.

Psychosocial family stressors can also contribute to or exacerbate the symptoms of ADHD.

Epidemiology

Studies of the prevalence of ADHD across the globe have generally reported that 5-10% of school-aged children are affected, although rates vary considerably by country, perhaps in part due to differing sampling and testing techniques. Rates may be higher if symptoms (inattention, impulsivity, hyperactivity) are considered in the absence of functional impairment. The prevalence rate in adolescent samples is 2-6%. Approximately 2% of adults have ADHD. ADHD is often underdiagnosed in children and adolescents. Youth with ADHD are often undertreated with respect to what is known about the needed and appropriate doses of medications. Many children with ADHD also present with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, including opposition defiant disorder, conduct disorder, learning disabilities, and anxiety disorders (see Table 30-3).

Pathogenesis

MRI studies indicate a loss of normal asymmetry in the brain, in addition to smaller brain volumes of specific structures, such as the prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia. Children with ADHD have approximately a 5-10% reduction in these brain structures. Functional MRI findings suggest low blood flow to the striatum. Functional MRI data suggest deficits in a widespread functional network in ADHD that include the striatum, prefrontal regions, parietal lobe, and temporal lobe. The prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia are rich in dopamine receptors. This knowledge, plus data about the dopaminergic mechanisms of action of medication treatment for ADHD, has led to the dopamine hypothesis, which postulates that disturbances in the dopamine system may be related to the onset of ADHD. Fluorodopa positron emission tomography scans also support the dopamine hypothesis through the identification of low levels of dopamine activity in adults.

Clinical Manifestations

Development of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) criteria leading to the diagnosis of ADHD has occurred mainly in field trials with children 5-12 yr of age (see Table 30-1). The current DSM-IV criteria state that the behavior must be developmentally inappropriate (substantially different from that of other children of the same age and developmental level), must begin before age 7 yr, must be present for at least 6 mo, must be present in 2 or more settings, and must not be secondary to another disorder. DSM-IV identifies 3 subtypes of ADHD. The 1st subtype, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, predominantly inattentive type, often includes cognitive impairment and is more common in females. The other 2 subtypes, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, combined type, are more commonly diagnosed in males. Clinical manifestations of ADHD may change with age. The symptoms may vary from motor restlessness and aggressive and disruptive behavior, which are common in preschool children, to disorganized, distractible, and inattentive symptoms, which are more typical in older adolescents and adults. ADHD is often difficult to diagnose in preschoolers because distractibility and inattention are often considered developmental norms during this period.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

A diagnosis of ADHD is made primarily in clinical settings after a thorough evaluation, including a careful history and clinical interview to rule in or to identify other causes or contributing factors; completion of behavior rating scales; a physical examination; and any necessary or indicated laboratory tests. It is important to systematically gather and evaluate information from a variety of sources, including the child, parents, teachers, physicians, and, when appropriate, other caretakers.

Clinical Interview and History

The clinical interview allows a comprehensive understanding of whether the symptoms meet the diagnostic criteria for ADHD. During the interview, the clinician should gather information pertaining to the history of the presenting problems, the child’s overall health and development, and the social and family history. The interview should emphasize factors that might affect the development or integrity of the central nervous system or reveal chronic illness, sensory impairments, or medication use that might affect the child’s functioning. Disruptive social factors, such as family discord, situational stress, and abuse or neglect, can result in hyperactive or anxious behaviors. A family history of 1st-degree relatives with ADHD, mood or anxiety disorders, learning disability, antisocial disorder, or alcohol or substance abuse might indicate an increased risk of ADHD and/or comorbid conditions.

Behavior Rating Scales

Behavior rating scales are useful in establishing the magnitude and pervasiveness of the symptoms, but are not sufficient alone to make a diagnosis of ADHD. There are a variety of well-established behavior rating scales that have obtained good results in discriminating between children with ADHD and control subjects. These measures include, but are not limited to, the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Rating Scale, the Conner Rating Scales (parent and teacher); the ADHD Index; the Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Checklist (SNAP); and the ADD-H: Comprehensive Teacher Rating Scale (ACTeRS). Other broadband checklists, such as the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL), are useful, particularly in instances where the child may be experiencing co-occurring problems in other areas (anxiety, depression, conduct problems).

Physical Examination and Laboratory Findings

There are no laboratory tests available to identify ADHD in children. The presence of hypertension, ataxia, or a thyroid disorder should prompt further diagnostic evaluation. Impaired fine motor movement and poor coordination and other soft signs (finger tapping, alternating movements, finger-to-nose, skipping, tracing a maze, cutting paper) are common, but they are not sufficiently specific to contribute to a diagnosis of ADHD. The clinician should also identify any possible vision or hearing problems. The clinician should consider testing for elevated lead levels in children who present with some or all of the diagnostic criteria, if these children are exposed to environmental factors that might put them at risk (substandard housing, old paint). Behavior in the structured laboratory setting might not reflect the child’s typical behavior in the home or school environment. Therefore, reliance on observed behavior in a physician’s office can result in an incorrect diagnosis. Computerized attentional tasks and electroencephalographic assessments are not needed to make the diagnosis, and compared to the clinical gold standard they are subject to false-positive and false-negative errors.

Differential Diagnosis

Chronic illnesses, such as migraine headaches, absence seizures, asthma and allergies, hematologic disorders, diabetes, childhood cancer, affect up to 20% of children in the U.S. and can impair children’s attention and school performance, either because of the disease itself or because of the medications used to treat or control the underlying illness (medications for asthma, steroids, anticonvulsants, antihistamines) (see Table 30-3). In older children and adolescents, substance abuse (Chapter 108) can result in declining school performance and inattentive behavior.

Sleep disorders, including those secondary to chronic upper airway obstruction from enlarged tonsils and adenoids, often result in behavioral and emotional symptoms, although such problems are not likely to be principal contributing causes of ADHD (Chapter 17). Behavioral and emotional disorders can cause disrupted sleep patterns.

Depression and anxiety disorders (Chapters 23 and 24) can cause many of the same symptoms as ADHD (inattention, restlessness, inability to focus and concentrate on work, poor organization, forgetfulness), but can also be comorbid conditions. Obsessive-compulsive disorder can mimic ADHD, particularly when recurrent and persistent thoughts, impulses, or images are intrusive and interfere with normal daily activities. Adjustment disorders secondary to major life stresses (death of a close family member, parents’ divorce, family violence, parents’ substance abuse, a move) or parent-child relationship disorders involving conflicts over discipline, overt child abuse and/or neglect, or overprotection can result in symptoms similar to those of ADHD.

Although ADHD is believed to result from primary impairment of attention, impulse control, and motor activity, there is a high prevalence of comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders (see Table 30-3). Of children with ADHD, 15-25% have learning disabilities, 30-35% have language disorders, 15-20% have diagnosed mood disorders, and 20-25% have coexisting anxiety disorders. Children with ADHD can also have co-occurring diagnoses of sleep disorders, memory impairment, and decreased motor skills.

Treatment

Psychosocial Treatments

Once the diagnosis of ADHD has been established, the parents and child should be educated with regard to the ways ADHD can affect learning, behavior, self-esteem, social skills, and family function. The clinician should set goals for the family to improve the child’s interpersonal relationships, develop study skills, and decrease disruptive behaviors.

Behaviorally Oriented Treatments

Treatments geared toward behavioral management often occur in the time frame of 8-12 sessions. The goal of such treatment is for the clinician to identify targeted behaviors that cause impairment in the child’s life (disruptive behavior, difficulty in completing homework, failure to obey home or school rules) and for the child to work on progressively improving his or her skill in these areas. The clinician should guide the parents and teachers in implementing rules, consequences, and rewards to encourage desired behaviors. In short-term comparison trials, stimulants have been more effective than behavioral treatments used alone; behavioral interventions are only modestly successful at improving behavior, but they may be particularly useful for children with complex comorbidities and family stressors, when combined with medication.

Medications

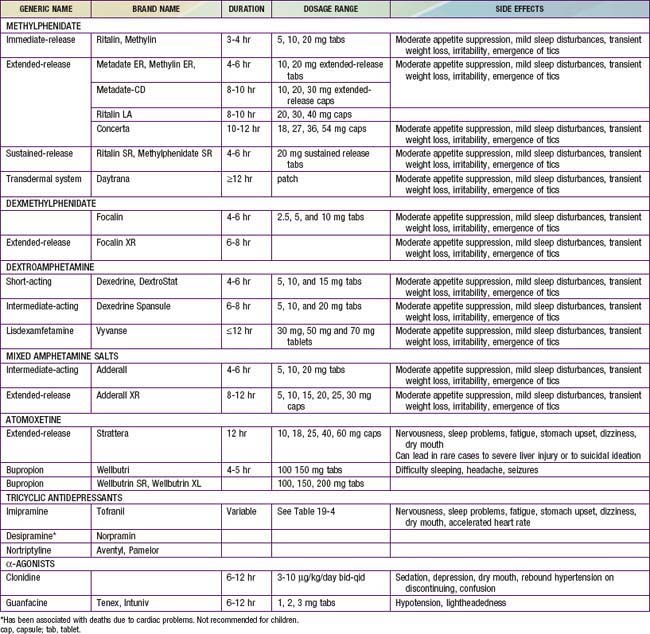

The most widely used medications for the treatment of ADHD are the psychostimulant medications, including methylphenidate (Ritalin, Concerta, Metadate, Focalin, Daytrana), amphetamine, and/or various amphetamine and dextroamphetamine preparations (Dexedrine, Adderall, Vyvanse) (Table 30-4). Longer-acting, once-daily forms of each of the major types of stimulant medications are available and facilitate compliance with treatment. The clinician should prescribe a stimulant treatment, either methylphenidate or an amphetamine compound. If a full range of methylphenidate dosages is used, approximately 25% of patients have an optimal response on a low (<20 mg/day), medium (20-50 mg/day), or high (>50 mg/day) daily dosage; another 25% will be unresponsive or will have side effects, making that drug particularly unpalatable for the family.

Over the first 4 wk, the physician should increase the medication dose as tolerated (keeping side effects minimal to absent) to achieve maximum benefit. If this strategy does not yield satisfactory results, or if side effects prevent further dose adjustment in the presence of persisting symptoms, the clinician should use an alternative class of stimulants that was not used previously. If a methylphenidate compound is unsuccessful, the clinician should switch to an amphetamine product. If satisfactory treatment results are not obtained with the 2nd stimulant, clinicians may choose to prescribe atomoxetine, a noradrenergic reuptake inhibitor that is superior to placebo in the treatment of ADHD in children, adolescents, and adults and that has been approved by the U.S Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for this indication. Atomoxetine should be initiated at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg/day and titrated over 1-3 wk to a maximum dosage of 1.2-1.8 mg/kg/day. Guanfacine, an antihypertension agent, is also FDA approved for the treatment of ADHD.

The clinician should consider careful monitoring of medication a necessary component of treatment in children with ADHD. When physicians prescribe medications for the treatment of ADHD, they tend to use lower than optimal doses. Optimal treatment usually requires somewhat higher doses than tend to be found in routine practice settings. All-day preparations are also useful to maximize positive effects and minimize side effects, and regular medication follow-up visits should be offered (4 or more times/yr) vs the twice-yearly medication visits often used in standard community-care settings.

Medication alone is not always sufficient to treat ADHD in children, particularly in instances where children have multiple psychiatric disorders or stressed home environments. When children do not respond to medication, it may be appropriate to refer them to a mental health specialist. Consultation with a child psychiatrist or psychologist can also be beneficial to determine the next steps for treatment, including adding other components and supports to the overall treatment program. Evidence suggests that children who receive careful medication management, accompanied by frequent treatment follow-up, all within the context of an educative, supportive relationship with the primary care provider, are likely to experience behavioral gains for up to 24 mo.

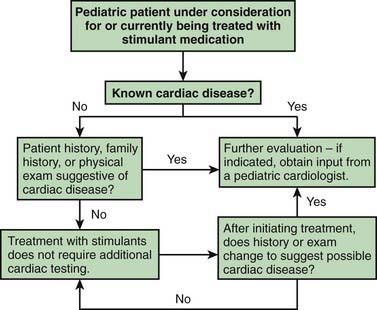

Stimulant drugs used to treat ADHD may be associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular events, including sudden cardiac death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in young adults and rarely in children. In some of the reported cases, the patient had an underlying disorder, such as hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, which is made worse by sympathomimetic agents. These events are rare, but they nonetheless warrant consideration before initiating treatment and during monitoring of treatment with stimulant medications. Children with a positive or personal family history of cardiomyopathy, or arrhythmias, or syncope will require an electrocardiogram and possible cardiology consultation before a stimulant is prescribed (Fig. 30-1).

Prognosis

A childhood diagnosis of ADHD often leads to persistent ADHD throughout the life span. From 60-80% of children with ADHD continue to experience symptoms in adolescence, and up to 40-60% of adolescents exhibit ADHD symptoms into adulthood. In children with ADHD, a reduction in hyperactive behavior often occurs with age. Other symptoms associated with ADHD can become more prominent with age, such as inattention, impulsivity, and disorganization, and these exact a heavy toll on young adult functioning. A variety of risk factors can affect children with untreated ADHD as they become adults. These risk factors include engaging in risk-taking behaviors (sexual activity, delinquent behaviors, substance use), educational underachievement or employment difficulties, and relationship difficulties. With proper treatment, the risks associated with the disorder can be significantly reduced.

Prevention

Parent training can lead to significant improvements in preschool children with ADHD symptoms, and parent training for preschool youth with ADHD can reduce oppositional behavior. To the extent that parents, teachers, physicians, and policymakers support efforts for earlier detection, diagnosis, and treatment, prevention of long-term adverse effects of ADHD on affected children’s lives should be reconsidered within the lens of prevention. Given the effective treatments for ADHD now available, and the well-documented evidence about the long-term effects of untreated or ineffectively treated ADHD on children and youth, prevention of these consequences should be within the grasp of physicians and the children and families with ADHD for whom we are responsible.

American Academy of Pediatrics/American Heart Association. American Academy of Pediatrics/American Heart Association clarification of statement on cardiovascular evaluation and monitoring of children and adolescents with heart disease receiving medications for ADHD: May 16, 2008. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2008;29(4):335.

Atkinson M, Hollis C. NICE guideline: attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2010;95:24-27.

Babcock T, Ornstein CS. Comorbidity and its impact in adult patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a primary care perspective. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:73-82.

Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, et al. Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: Adaptive functioning in major life activities. J Am Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:192-202.

Bouchard MF, Bellinger DC, Wright RO, et al. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and urinary metabolites of organophosphate pesticides. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e1270-e1277.

Brookes KJ, Mill J, Guindalini C, et al. A common haplotype of the dopamine transporter gene associated with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and interacting with maternal use of alcohol during pregnancy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:74-81.

Caspi A, Langley K, Milne B, et al. A replicated molecular genetic basis for subtyping antisocial behavior in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:203-210.

Eigenmann PA, Haenggeli CA. Food colourings, preservatives, and hyperactivity. Lancet. 2007;370:1524-1525.

Gould MS, Walsh BT, Munfakh JL, et al. Sudden death and use of stimulant medications in youths. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:992-1101.

Greenhill L, Kollins S, Abikoff H, et al. Efficacy and safety of immediate-release methylphenidate treatment for preschoolers with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:1284-1293.

Hammerness P, Wilens T, Mick E, et al. Cardiovascular effects of longer-term, high-dose OROS methylphenidate in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Pediatr. 2009;155:84-89.

Harpin VA. Medication options when treating children and adolescents with ADHA: interpreting the NICE guidance 2006. Arch Dis Child Pract Ed. 2008;93:58-66.

Jones K, Daley D, Hutchings J, et al. Efficacy of the Incredible Years Programme as an early intervention for children with conduct problems and ADHD: long-term follow-up. Child Care Health Dev. 2008;34:380-390.

Kendall T, Taylor E, Perez A, et al. Diagnosis and management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children, young people, and adults: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:751-754.

Knight M. Stimulant-drug therapy for attention-deficit disorder (with or without hyperactivity) and sudden cardiac death. Pediatrics. 2007;119:154-155.

Kollins S, Greenhill L, Swanson J, et al. Rationale, design, and methods of the preschool ADHA treatment study (PATS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:1275-1283.

Langberg JM, Brinkman WB, Lichtenstein PK, et al. Interventions to promote the evidence-based care of children with ADHD in primary-care settings. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:477-487.

McCann D, Barrett A, Cooper A, et al. Food additives and hyperactive behaviour in 3-year-old and 8/9-year-old children in the community: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1560-1567.

2010 The Medical Letter: Guanfacine extended-release (Intuniv) for ADHD. Med Lett. 2010;52:82.

Mosholder AD, Gelperin K, Hammad TA, et al. Hallucinations and other psychotic symptoms associated with the use of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder drugs in children. Pediatrics. 2009;123:611-616.

Newcorn JH. Managing ADHD and comorbidities in adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(2):e40.

Newcorn JH, Kratochvil CJ, Allen AJ, et al. Atomoxetine and osmotically released methylphenidate for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: acute comparison and differential response. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:721-730.

Newcorn JH, Sutton VK, Weiss MD, et al. Clinical responses to atomoxetine in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the integrated data exploratory analysis (IDEA) study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:511-518.

Nutt DJ, Fone K, Asherson P, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for management of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adolescents in transition to adult services and in adults: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21:10-41.

Okie S. ADHD in adults. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2637-2641.

Pelsser LM, Frankena K, Toorman J, et al. Effects of restricted elimination diet on the behaviour of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (INCA study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:494-503.

Perrin JM, Friedman RA, Knilans TK. Cardiovascular monitoring and stimulant drugs for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2008;122:451-453.

Safren SA, Sprich S, Mimiaga MJ, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs relaxation with educational support for medication—adults with ADHD and persistent symptoms. JAMA. 2010;304:875-880.

Shum SBM, Pang MYC. Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder have impaired balance function: involvement of somatosensory, visual, and vestibular systems. J Pediatr. 2009;155:245-249.

Silk TJ, Vance A, Rinehart N, et al. Dysfunction in the fronto-parietal network in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): an fMRI study. Brain Imaging Behav. 2008;2:1931.

Smith AK, Mick E, Faraone SV. Advances in genetic studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2009;11:143-148.

Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Welcome SE, et al. Cortical abnormalities in children and adolescents with attention-deficit disorder. Lancet. 2008;362:1699-1707.

Spencer TJ. ADHD and comorbidity in childhood. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(supp 8):27-31.

Thomas PE, Carlo WE, Decker JA, et al. Impact of the American Heart Association scientific statement on screening electrocardiograms and stimulant medications. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(2):166-170.

Wilens TE, Prince JB, Spencer TJ, et al. Stimulants and sudden death: what is a physician to do? Pediatrics. 2006;118:1215-1219.

Zwi M, Clamp P. Injury and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. BMJ. 2008;337:1179-1180.