Chapter 25 Suicide and Attempted Suicide

Youth suicide is a major and preventable public health problem. It ranks as the 3rd and 4th leading causes of death among young people ages 15-24 yr and 10-14 yr, respectively.

Each year, there are approximately 10 suicides for every 100,000 youngsters younger than 19 yr, an estimated 12 suicides every day. Morbidity from suicide attempts is high, with approximately 2 million young people attempting suicide each year and almost 700,000 receiving medical attention. There are a number of psychologic, social, cultural, and environmental risk factors for suicide, and knowledge of these risk factors can facilitate identification of youths at highest risk.

Epidemiology

Suicide Completions

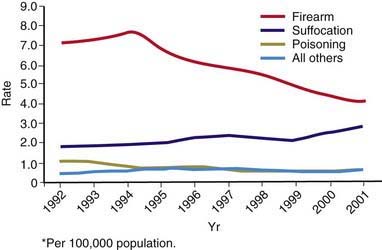

Suicide is very rare before puberty. Rates of completed suicide increase steadily across the teen years and into young adulthood, peaking in the early 20s. Males complete suicide at a rate 4 times that of females and represent 79.4% of all suicides. Firearms remain the most commonly used method of completing suicide for males, whereas females are more likely to complete suicide by poisoning (Fig. 25-1). In the past 60 yr, the suicide rate has quadrupled among 15-24 yr old males and has doubled for females of the same age. The male:female ratio for completed suicide rises with age from 3 : 1 in young children to approximately 4 : 1 in 15-24 yr olds, and to greater than 6 : 1 among 20-24 yr olds.

Figure 25-1 Annual suicide rates among persons aged 15-19 yr, by year and method, United States, 1992-2001.

(From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Methods of suicide among persons aged 10–19 years, United States, 1992–2001, MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 53:471–474, 2004.)

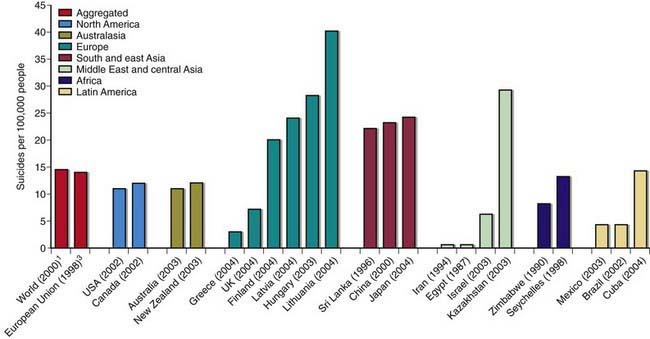

The ethnic groups with the highest risk for completed suicide are American Indians and Alaska Natives. Within this population, suicide is the second leading cause of death, accounting for nearly 1 in 5 deaths among youth ages 15-24 yr. The ethnic groups with the lowest risk are African-Americans, Hispanics, Asians, and Pacific Islanders. The suicide rate among African-American, Hispanic, and other minority males has continued to increase, and the rate among white males has remained steady. Suicide risk also varies in different countries (Fig. 25-2).

Suicide Attempts

It is estimated that for every completed youth suicide, as many as 200 suicide attempts are made. Ingestion of medication is the most common method of attempted suicide. The 15 to 19 yr old age group is the most likely to intentionally harm themselves by ingestion, receive treatment in emergency departments, and survive. Attempts are more common in girls than boys (approximately 3 : 1), and in Hispanic girls than their non-Hispanic white or non-Hispanic African-American counterparts. Gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths are also at increased risk for suicide attempts. Suicide attempts among African-American adolescent males have more than doubled from 1991 to 2001. Attempters who have made prior suicide attempts, who used a method other than ingestion, and who still want to die are at increased risk for completed suicide.

Suicide Ideation

Based on the 2007 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 14.5% of students in grades 9 through 12 reported that they had seriously considered attempting suicide in the 12 mo preceding the survey (18.7% of females and 10.3% of males). Nearly 7% of students reported that they had actually attempted suicide at least once during the same period.

Risk Factors

In addition to age, race and ethnicity, and a history of a previous suicide attempt, there are multiple risk factors that predispose youths to suicide.

Pre-existing Psychiatric Illness

The great majority (estimated at 90%) of youths who complete suicide have a pre-existing psychiatric illness, most commonly major depression (Chapter 24.1). Among girls, chronic anxiety, especially panic disorder, also is associated with suicide completion (Chapter 23). Among boys, conduct disorder and substance use convey increased risk. Comorbidity of a substance use disorder (Chapter 108), a mood disorder (Chapter 24), and conduct disorder (Chapter 27) has been linked to suicide by firearm.

Cognitive Distortions

Negative self-attributions can contribute to the hopelessness that is commonly associated with suicidality; hopelessness may contribute to ~55% of the explained variance in continued suicidal ideation. Many suicidal youth hold negative views of their own competence, have poor self-esteem, and have difficulty identifying sources of support or reasons to live. Many youngsters lack the coping strategies necessary to manage strong emotions and instead tend to catastrophize and engage in all-or-nothing thinking.

Social, Cultural, and Environmental Factors

Of children and adolescents who attempt suicide, 65% can name a precipitating event for their action. Most adolescent suicide attempts are precipitated by stressful life events, such as academic or social problems, being bullied, trouble with the law, family instability, questioning one’s sexual orientation, a newly diagnosed medical condition, or a recent or anticipated loss. Suicide may also be precipitated by exposure to news of another person’s suicide or by reading about or viewing a suicide portrayed in a romantic light in the media.

For some recent immigrants, suicidal ideation is associated with high levels of acculturative stress, especially in the context of family separation and limited access to supportive resources. Physical and sexual abuse can also increase one’s risk of suicide; 15-20% of female suicide attempters had a history of abuse. There is a more general association between family conflict and suicide attempts; this association is strongest in children and early adolescents. Family psychopathology and a family history of suicidal behavior convey excess risk. Supportive social relations with peers, parents, and school personnel have an interactive relationship in mitigating the risk of suicide among youth.

Assessment and Intervention

Assessment of suicidal ideation should be a regular part of visits with young patients. Two thirds of youths who commit suicide visit a physician in the month before they kill themselves. When not specifically asked, youth are less likely to disclose depression, suicidal thoughts, and patterns of drug use. Distress is not always expressed in the same ways among persons from different cultural backgrounds.

Evaluating the presence and degree of suicidality and underlying risk factors is complex; clinical assessment is best conducted by a qualified mental health professional. All suicidal ideation and attempts should be taken seriously and require a thorough assessment to evaluate the youth’s current state of mind, underlying psychiatric conditions, and ongoing risk of harm. Gathering information from multiple sources and by varied culturally and developmentally sensitive techniques are essential in evaluating suicidal risk indicators.

The reliability and validity of interview reporting of children and adolescents may be affected by their level of cognitive development and their understanding of the relationship between their emotions and behavior. Confirmation of the youth’s suicidal behavior can be obtained from information gathered by interviewing others who know the child or adolescent. There is often a discrepancy between child and parent reports, with both children and adolescents being more likely to tell of suicidal ideation and suicidal actions than their parents.

Ideation can be assessed by the following series of questions: “Did you ever feel so upset that you wished you were not alive or wanted to die?” “Did you ever do something that you knew was so dangerous that you could get hurt or killed by doing it?” “Did you ever hurt yourself or try to hurt yourself?” “Did you ever try to kill yourself?”

The assessment of attempts should include a detailed exploration of the hours immediately preceding the attempt to identify precipitants, as well as the circumstances of the attempt itself to identify intent and potential lethality. Attempters at greatest risk for completed suicide are those who are male; have made a prior suicide attempt; have current ideation, intent, a written note, and a plan; have a mental status altered by depression, mania, anxiety, intoxication, psychosis, hopelessness, rage, humiliation, or impulsivity; and lack supportive family members who can provide supervision, safeguard the home (prevent access to firearms, medications, alcohol, drugs), and ensure adherence to treatment recommendations (Table 25-1).

Table 25-1 CHECKLISTS FOR ASSESSING CHILD OR ADOLESCENT SUICIDE ATTEMPTERS IN AN EMERGENCY DEPARTMENT OR CRISIS CENTER

ATTEMPTERS AT GREATER RISK FOR SUICIDE

Suicidal History

Demographics

Mental State

LOOK FOR SIGNS OF CLINICAL DEPRESSION:

LOOK FOR SIGNS OF MANIA OR HYPOMANIA:

From American Foundation for Suicide Prevention: Today’s suicide attempter could be tomorrow’s suicide (poster), New York, 1999, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, 1-888-333-AFSP.

Youth with these risk factors generally require inpatient level of care to ensure safety, clarify diagnosis, and comprehensively plan treatment. For those youth suitable for treatment in the outpatient setting, an appointment should be scheduled within a few days with a mental health professional. Ideally this appointment should be scheduled before leaving the assessment venue, because 50% of those who attempt suicide fail to complete the follow-up referral. A procedure should be in place to contact the family if the family fails to complete the referral. Therapies that have been found to be helpful with suicidal youth include cognitive-behavioral therapy, dialectical behavioral therapy, and interpersonal therapy. Psychotropic medications are used adjunctively to treat underlying psychiatric disorders.

Prevention

At present there is insufficient evidence to either support or refute universal suicide prevention programs. Screening for suicidality is fraught with problems related to low specificity of the screening instrument, poor acceptability among school administrators, and paucity of referral sites. Gatekeeper (e.g., student support personnel) training is effective in improving skills among school personnel and is highly acceptable to administrators but has not been shown to prevent suicide. Peer helpers have not been shown to be efficacious.

One school-based prevention program (the Signs of Suicide program) has shown some preventive potential based on the results from a randomized trial among high school students. In this program, a curriculum to raise awareness of suicide is combined with a brief screening for depression and other risk factors associated with suicide. The curriculum promotes the concept that suicide is directly related to mental illness, typically depression, and is not a normal reaction to stress. Students are taught to recognize the signs of suicide and depression in themselves and others, and they are taught the specific action steps necessary for responding to these signs.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with suicidal behavior. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:24S-51S.

American Association of Suicidality. Fact sheets. (website) www.suicidology.org/web/guest/stats-and-tools/fact-sheets Accessed February 12, 2010

Aseltine RH, DeMartino R. An outcome evaluation of the SOS Suicide Prevention Program. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:446-451.

Brent DA, Emslie GJ, Clarke GN, et al. Predictors of spontaneous and systematically assessed suicidal adverse events in the treatment of SSRI-resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) study. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:418-426.

Brezo J, Barker ED, Paris J, et al. Childhood trajectories of anxiousness and disruptiveness as predictors of suicide attempts. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 162, 2008. 1813–1021

Bridge JA, Greenhouse JB, Weldon AH. Suicide trends among youths aged 10 to 19 years in the United States, 1996-2005. JAMA. 2008;300:1025-1026.

Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment. JAMA. 2007;297:1683-1696.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol and suicide among racial/ethnic populations—17 states, 2005-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:637-642.

Hawton K. Completed suicide after attempted suicide. BMJ. 2010;341:c3064.

Hawton K, van Heeringen K. Suicide. Lancet. 2009;373:1372-1380.

Klomek Brunstein A, Sourander A, Niemela S, et al. Childhood bullying behaviors as a risk for suicide attempts and completed suicides: a population-based birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:254-261.

Kuchar PS, DiGuiseept C. Screening for suicide risk. In: Guide to clinical preventive services, second edition: mental disorders and substance abuse. Washington, DC: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; 2003.

National Institute of Mental Health. Suicide in the U.S.: statistics and prevention. (website) www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/suicide-in-the-us-statistics-and-prevention/index.shtml Accessed February 12, 2010

Qin P, Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB. Frequent change of residence and risk of attempted and completed suicide among children and adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:628-632.

Schneeweiss S, Patrick AR, Solomon DH, et al. Comparative safety of antidepressant agents for children and adolescents regarding suicidal acts. Pediatrics. 2010;125:876-888.

Wilcox HC, Storr CL, Breslau N. Posttraumatic stress disorder and suicide attempts in a community sample of urban American young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:305-311.

Winters NC, Myers K, Proud L. Ten-year review of rating scales. III: Scales assessing suicidality, cognitive style, and self-esteem. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:1150-1181.