Chapter 108 Substance Abuse

Adolescents are influenced by a complex interaction between biologic and psychosocial development, environmental messages, and societal attitudes about the use of substances such as alcohol, tobacco, or marijuana. Occasional or situational use of certain substances such as alcohol may be viewed as “normative” given the proportion of youths who report some experience with these substances. Others view the potential for adverse outcomes even with occasional use in immature adolescents, such as motor vehicle crashes and other injuries, sufficient justification to consider any drug use in younger adolescents a considerable risk.

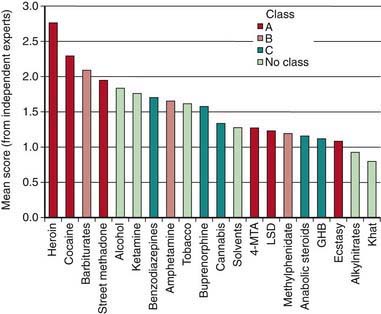

Individuals who initiate drug use at an early age are at a greater risk for becoming addicted than those who try drugs in early adulthood. Drug use in younger, less experienced adolescents can act as a substitute for developing age-appropriate coping strategies and enhance vulnerability to poor decision-making. The first use of the most commonly used drugs occurs before age 18 yr, with 88% of people reporting first alcohol use <21 yr old, the legal drinking age in the USA. Inhalants have been identified as a popular first drug for youth in grade 8. When drug use begins to negatively alter functioning in adolescents at school and at home, and risk-taking behavior is seen, intervention is warranted. Serious drug use is not an isolated phenomenon. It occurs across every segment of the population and is one of the most challenging public health problems facing society. The challenge to the clinician is to identify youths at risk for substance abuse and offer early intervention. The challenge to the community and society is to create norms that decrease the likelihood of adverse health outcomes for adolescents and promote and facilitate opportunities for adolescents to choose healthier and safer options. Recognizing those drugs with the greatest harm, and at times focusing on harm reduction with or without abstinence, is an important modern approach to adolescent substance abuse (Figs. 108-1, 108-2).

Figure 108-1 Mean harm scores for 20 substances as determined by an expert panel based on 3 criteria: physical harm to user; potential for dependence; and effect on family, community, and society. Classification under the Misuse of Drugs Act, when appropriate, is shown by the color of each bar. Class A drugs are deemed potentially most dangerous; class C least dangerous.

(From Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, et al: Development of a rational scale to access the harm of drugs of potential misuse, Lancet 369:1047–1053, 2007.)

Figure 108-2 Protection and risk model for distal and proximal determinants of risky substance use and related harms.

(From Toumbourou JW, Stockwell T, Neighbors C, et al: Interventions to reduce harm associated with adolescent substance use, Lancet 369:1391–1401, 2007.)

Etiology

Substance abuse is biopsychosocially determined (see Fig. 108-2). Biologic factors, including genetic predisposition, are established contributors. Behaviors such as rebelliousness, poor school performance, delinquency, and criminal activity and personality traits such as low self-esteem, anxiety, and lack of self-control are frequently associated with or predate the onset of drug use. Psychiatric disorders are often co-morbidly associated with adolescent substance use. Conduct disorders and antisocial personality disorders are the most common diagnoses coexisting with substance abuse, particularly in males. Teens with depression (Chapter 24), attention deficit disorder (Chapter 30), and eating disorders (Chapter 26) have high rates of substance use. The determinants of adolescent substance use and abuse are explained using a number of theoretical models, with factors at the individual level, the level of significant relationships with others, and the level of the setting or environment. Models include a balance of risk and protective or coping factors that tend to account for individual differences among adolescents with similar risk factors who escape adverse outcomes.

Risk factors for adolescent drug use may differ from those associated with adolescent drug abuse. Adolescent use is more commonly related to social and peer factors, whereas abuse is more often a function of psychologic and biologic factors. The likelihood that an otherwise normal adolescent would experiment with drugs may be dependent on the availability of the drug to the adolescent, the perceived positive or otherwise functional value to the adolescent, the perceived risk associated with use, and the presence or absence of restraints as determined by the adolescent’s cultural or other important value systems. An abusing adolescent may have genetic or biologic factors coexisting with dependence on a particular drug for coping with day-to-day activities.

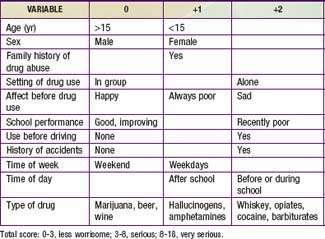

Specific historical questions can assist in determining the severity of the drug problem through a rating system (Table 108-1). The type of drug used (marijuana versus heroin), the circumstances of use (alone or in a group setting), the frequency and timing of use (daily before school versus rarely on a weekend), the premorbid mental health status (depressed versus happy), as well as the teenager’s general functional status should all be considered in evaluating any youngster found to be abusing a drug. The stage of drug use/abuse should also be considered (Table 108-2). A teen may spend months or years in the experimentation phase trying a variety of illicit substances including the most common drugs, cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana. It is not until regular use of drugs resulting in negative consequences (problem use) that the teen typically become identified as having a problem, either by parents, teachers, or a physician. Certain protective factors play a part in buffering the risk factors as well as assisting in anticipating the long-term outcome of experimentation. Having emotionally supportive parents with open communication styles, involvement in organized school activities, having mentors or role models outside of the home, and recognition of the importance of academic achievement are examples of the important protective factors.

Table 108-2 STAGES OF ADOLESCENT SUBSTANCE ABUSE

| STAGE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 |

Epidemiology

The National Survey on Drug Use and Health is an annual survey of persons(s) from a randomly selected set of households in the USA but does not capture those who refuse to participate in the survey. School-based surveys (Monitoring the Future study and Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance) are limited to those youth enrolled and attending school and do not capture school dropouts or those youth in the juvenile detention system. The rates of drug use across surveys are not dramatically different and certain observations are consistent across surveys.

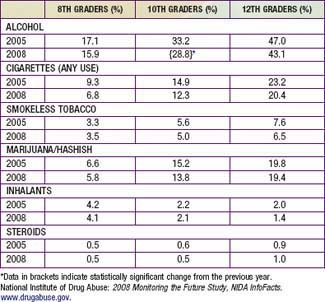

In the USA, alcohol and cigarettes and marijuana are the most commonly reported substances used among teens (Table 108-3). The prevalence of substance use and associated risky behaviors vary by age, gender, race/ethnicity, and other sociodemographic factors. Younger teenagers tend to report less use of drugs than do older teenagers, with the exception of inhalants (in 2008, 15.7% in 8th grade, 12.8% in 10th grade, 9.9% in 12th grade). Males have higher rates of both licit and illicit drug use than females, with greatest differences seen in their higher rates of frequent use of smokeless tobacco, cigars, and anabolic steroids. In school surveys, drug use patterns of Hispanics tend to fall in between whites and African-Americans, with the exception of 12th grade Hispanics reporting highest rates of crack cocaine, heroin (injected), and crystal methamphetamine use. African-Americans report less use of drugs across all drug categories with dramatically lower levels of cigarette use in comparison to whites.

Table 108-3 THIRTY DAY PREVALENCE USE OF ALCOHOL, CIGARETTES, MARIJUANA, AND INHALANTS IN 8TH GRADERS, 10TH GRADERS, AND 12TH GRADERS, 2005 AND 2008

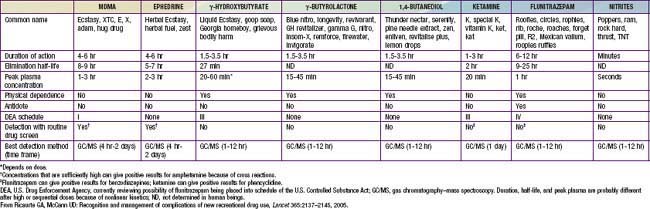

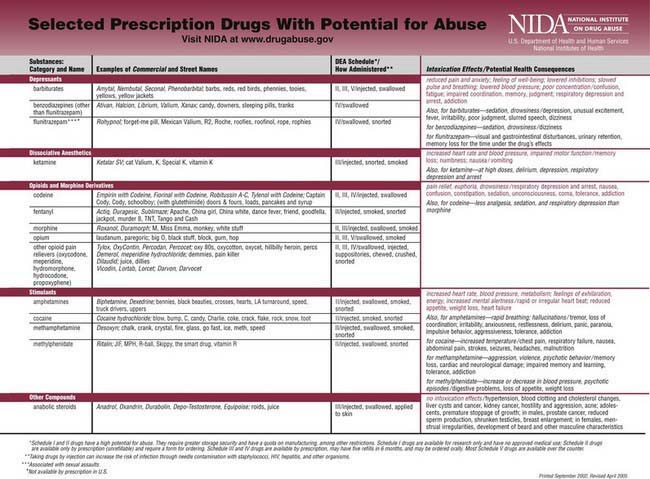

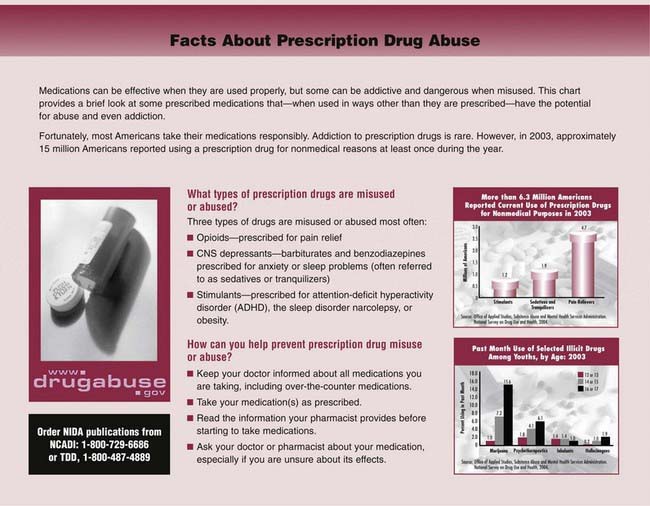

In examining trends in drug use, positive findings are that fewer students reported cigarette, alcohol, or stimulant use than in the previous 5 yr. Marijuana use has leveled off after a general decline. (Past year use of marijuana in 2008: 10.9% in 8th graders, 23.9% in 10th graders, 32.4% in 12th graders.) Prescription drug abuse is increasing in prevalence with 15.4% of high school seniors reported taking a prescription drug nonmedically in the last yr (Table 108-4). For many adolescents and young adults, prescription drug use is the most common abused category of drugs and includes opioids, drugs that treat ADHD, antianxiety agents, dextromethorphan, antihistamines, sedatives, and tranquilizers. Many of these agents can be found in the parents’ home, some are over-the-counter, while others are purchased from drug dealers at schools and colleges. Many users believe that these drugs are benign because they are obtained by prescription or purchased at a pharmacy. Club drugs, commonly used at all-night dance parties, are increasingly popular among older adolescents and young adults (Table 108-5). These drugs have significant side effects especially if taken in combination with alcohol or other drugs. Anterograde amnesia, impaired learning ability, disassociation, and breathing difficulties may occur. Repeated use may lead to tolerance, cravings for the drug, and withdrawal effects including anxiety, tremors, and sweating.

Table 108-4 SELECTED PRESCRIPTION DRUGS WITH POTENTIAL FOR ABUSE

The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and other Drugs results (4 surveys over 12 yr among European students) demonstrate declines in smoking in most of the surveyed nations; since 1995 the overall average of “smoked in the last 30 days” declined 4% to the current level of 29%. Average alcohol use in the past 12 mo (82%) remains essentially stable but heavy episodic drinking appears to have increased somewhat. There is substantial between-country variation in alcohol use. Marijuana remains the primary illicit drug used; overall in 2007 19% of youth reported ever having used marijuana, compared to only 7% reporting use of other illicit drugs.

Clinical Manifestations

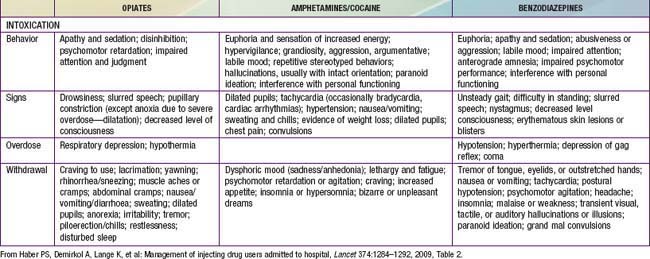

Although manifestations vary by the specific substance of use, adolescents who use drugs often present in an office setting with no obvious physical findings. Drug use is more frequently detected in adolescents who experience trauma such as motor vehicle crashes, bicycle injuries, or violence. Eliciting appropriate historical information regarding substance use, followed by blood alcohol and urine drug screens is recommended in emergency settings. An adolescent presenting to an emergency setting with an impaired sensorium should be evaluated for substance use as a part of the differential diagnosis (Table 108-6). Screening for substance use is recommended for patients with psychiatric and behavioral diagnoses. Other clinical manifestations of substance use are associated with the route of use; intravenous drug use is associated with venous “tracks” and needle marks, while nasal mucosal injuries are associated with nasal insufflation of drugs. Seizures can be a direct effect of drugs such as cocaine and amphetamines or an effect of drug withdrawal in the case of barbiturates or tranquilizers.

Table 108-6 THE MOST COMMON TOXIC SYNDROMES

| ANTICHOLINERGIC SYNDROMES | |

| Common signs | Delirium with mumbling speech, tachycardia, dry, flushed skin, dilated pupils, myoclonus, slightly elevated temperature, urinary retention, and decreased bowel sounds. Seizures and dysrhythmias may occur in severe cases. |

| Common causes | Antihistamines, antiparkinsonian medication, atropine, scopolamine, amantadine, antipsychotic agents, antidepressant agents, antispasmodic agents, mydriatic agents, skeletal muscle relaxants, and many plants (notably jimson weed and Amanita muscaria). |

| SYMPATHOMIMETIC SYNDROMES | |

| Common signs | Delusions, paranoia, tachycardia (or bradycardia if the drug is a pure α-adrenergic agonist), hypertension, hyperpyrexia, diaphoresis, piloerection, mydriasis, and hyperreflexia. Seizures, hypotension, and dysrhythmias may occur in severe cases. |

| Common causes | Cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine (and its derivatives 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxyethamphetamine, and 2,5-dimethoxy-4-bromoamphetamine), and over-the-counter decongestants (phenylpropanolamine, ephedrine, and pseudoephedrine). In caffeine and theophylline overdoses, similar findings, except for the organic psychiatric signs, result from catecholamine release. |

| OPIATE, SEDATIVE, OR ETHANOL INTOXICATION | |

| Common signs | Coma, respiratory depression, miosis, hypotension, bradycardia, hypothermia, pulmonary edema, decreased bowel sounds, hyporeflexia, and needle marks. Seizures may occur after overdoses of some narcotics, notably propoxyphene. |

| Common causes | Narcotics, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, ethchlorvynol, glutethimide, methyprylon, methaqualone, meprobamate, ethanol, clonidine, and guanabenz. |

| CHOLINERGIC SYNDROMES | |

| Common signs | Confusion, central nervous system depression, weakness, salivation, lacrimation, urinary and fecal incontinence, gastrointestinal cramping, emesis, diaphoresis, muscle fasciculations, pulmonary edema, miosis, bradycardia or tachycardia, and seizures. |

| Common causes | Organophosphate and carbamate insecticides, physostigmine, edrophonium, and some mushrooms. |

From Kulig K: Initial management of ingestions of toxic substances, N Engl J Med 326:1678, 1992.

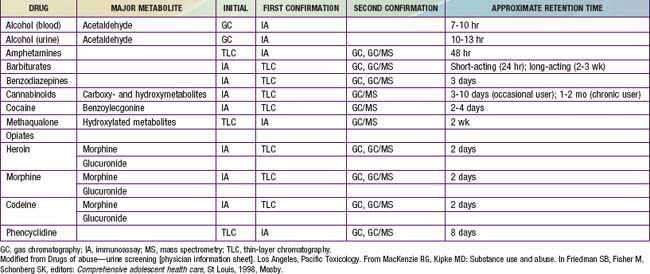

Screening for Substance Abuse Disorders

In a primary care setting the annual health maintenance examination provides an opportunity for identifying adolescents with substance use or abuse issues. The direct questions as well as the assessment of school performance, family relationships, and peer activities may necessitate a more in-depth interview if there are suggestions of difficulties in those areas. Additionally there are several self-report screening questionnaires available with varying degrees of standardization, length, and reliability. The CRAFFT mnemonic is specifically designed to screen for adolescents’ substance use in the primary setting (Table 108-7). Privacy and confidentiality need to be considered when asking the teen about specifics of their substance experimentation or use. Interviewing the parents can provide additional perspective on early warning signs that go unnoticed or disregarded by the teen. Examples of early warning signs of teen substance use are change in mood, appetite, or sleep pattern; decreased interest in school or school performance; loss of weight; secretive behavior about social plans; or valuables such as money or jewelry missing from the home. The use of urine drug screening is recommended when select circumstances are present: (1) psychiatric symptoms to rule out co-morbidity or dual diagnoses, (2) significant changes in school performance or other daily behaviors, (3) frequently occurring accidents, (4) frequently occurring episodes of respiratory problems, (5) evaluation of serious motor vehicular or other injuries, and (6) as a monitoring procedure for a recovery program. Table 108-8 demonstrates the types of tests commonly used for detection by substance, along with the approximate retention time between the use and the identification of the substance in the urine. Most initial screening uses an immunoassay method such as the enzyme-multiplied immunoassay technique followed by a confirmatory test using highly sensitive, highly specific gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. The substances that can cause false-positive results should be considered, especially when there is a discrepancy between the physical findings and the urine drug screen result. In 2007 the American of Academy of Pediatrics released guidelines that strongly discourage home-based or school-based testing.

Table 108-7 CRAFFT MNEMONIC TOOL

Adapted from Anglin TM: Evaluation by interview and questionnaire. In Schydlower M, editor: Substance abuse: a guide for health professionals, ed 2, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2002, American Academy of Pediatrics, p 69.

Diagnosis

Substance abuse is characterized by a maladaptive pattern of use indicated by continued use despite serious consequences or physical harm. Chemical dependence can be defined as a chronic and progressive disease process characterized by loss of control over use, compulsion, and the establishment of an altered state where one requires continued administration of a psychoactive substance in order to feel good or to avoid feeling bad. Diagnosing substance abuse rests on the realization that all children and adolescents are at risk but that some are at substantially more risk than others. Specific diagnostic codes are assigned to substance abuse and substance dependence (Table 108-9). These criteria are used in adults and have limitations in use with adolescents due to differing patterns of use, developmental implications, and other age-related consequences; an additional adolescent-sensitive set of criteria specifically for diagnostic use has not been developed. Adolescents who meet diagnostic criteria should be referred to a program for substance abuse treatment unless the primary care physician has additional training in addiction medicine.

Table 108-9 DSM-IV-TR DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND SUBSTANCE DEPENDENCE

SUBSTANCE ABUSE: A maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinical significant impairment of distress as manifested by one or more of the following criteria:

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

Complications

Substance use in adolescence is associated with co-morbidities and acts of juvenile delinquency. Youth may engage in other high risk behaviors such as robbery, burglary, drug dealing, or prostitution for the purpose of acquiring the money necessary to buy drugs or alcohol. Regular use of any drug eventually diminishes judgment and is associated with unprotected sexual activity with its consequences of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, as well as physical violence and trauma. Drug and alcohol use is closely associated with trauma in the adolescent population. Several studies of adolescent trauma victims have identified cannabinoids and cocaine in blood and urine samples in significant proportions (40%), in addition to the more common identification of alcohol. Any use of injected substances involves the risk of hepatitis B and C viruses as well as HIV.

Treatment

Adolescent drug abuse is a complex condition requiring a multidisciplinary approach that attends to the needs of the individual, not just drug use. Three decades of research analyzing effective drug abuse treatment have yielded 13 fundamental principles for treatment. In brief these include accessibility to treatment; utilizing a multidisciplinary approach; employing individual or group counseling; offering mental health services; monitoring of drug use while in treatment; and understanding that recovery from drug abuse/addiction may involve multiple relapses. For most patients, remaining in treatment for a minimum period of 3 mo will result in a significant improvement.

Prognosis

For adolescent substance abusers who have been referred to a drug treatment program, positive outcomes are directly related to regular attendance in post-treatment groups. For males with learning problems or conduct disorder, their outcomes are poorer than those without such disorders. Peer use patterns and parental use have a major influence on outcome for males. For females, factors such as self-esteem and anxiety are more important influences on outcomes. The chronicity of a substance use disorder makes relapse an issue that must always be kept in mind when managing patients after treatment, and appropriate assistance from a health professional qualified in substance abuse management should be obtained.

Prevention

Preventing drug use among children and teens requires prevention efforts aimed at the individual, family, school, and community levels. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has identified essential principles of successful prevention programs. Programs should enhance protective factors (parent support) and reduce risk factors (poor self-control); should address all forms of drug abuse (legal and illegal); should address the specific type(s) of drug abuse within an identified community; and should be culturally competent to improve effectiveness. See Table 108-10 for examples of risk factors and protective factors within those domains. The highest risk periods for substance use in children and adolescents are during life transitions such as the move from elementary school to middle school, or from middle school to high school. Prevention programs need to target these emotionally and socially intense times for teens in order to adequately anticipate potential substance use or abuse. Examples of effective research-based drug abuse prevention programs featuring a variety of strategies are listed on the NIDA website (www.drugabuse.gov), and on the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention website (www.prevention.samhsa.gov).

Table 108-10 DOMAINS OF RISK AND PROTECTIVE FACTORS FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE PREVENTION

| RISK FACTORS | DOMAIN | PROTECTIVE FACTORS |

|---|---|---|

| Early aggressive behavior | Individual | Self-control |

| Lack of parental supervision | Family | Parental monitoring |

| Substance abuse | Peer | Academic competence |

| Drug availability | School | Anti–drug use policies |

| Poverty | Community | Strong neighborhood attachment |

From National Institute on Drug Abuse: Preventing drug use among children and adolescents. A research based guide for parents, educators, and community leaders. NIH publication No. 04-4212(B), ed 2, Bethesda, MD, 2003, National Institute on Drug Abuse.

108.1 Alcohol

Alcohol is the most popular drug among teens. By 12th grade, close to 75% of adolescents in U.S. high schools report ever having an alcoholic drink, with 24% having their first drink before age 13 yr; rates are even higher among European youth. Multiple factors can affect a young teen’s risk of developing a drinking problem at an early age (Table 108-11). Moreover, 30% of high school seniors admit to combining drinking behaviors with other risky behaviors such as driving or taking additional substances. Binge drinking remains especially problematic among the older teens and young adults. Thirty-six percent of high school seniors report having 5 or more drinks in a row in the last 30 days. Teens with binge drinking patterns are more likely to be assaulted, engage in high risk sexual behaviors, have academic problems, and acquire injuries than those teens without binge drinking patterns.

Table 108-11 RISK FACTORS FOR A TEEN DEVELOPING A DRINKING PROBLEM

FAMILY RISK FACTORS

INDIVIDUAL RISK FACTORS

Alcohol contributes to more deaths in young individuals than all the illicit drugs combined. Among studies of adolescent trauma victims, alcohol is reported to be present in 32-45% of hospital admissions. Motor vehicle crashes are the most frequent type of event associated with alcohol use, but the injuries spanned several types including self-inflicted wounds.

Pharmacology and Pathophysiology

Alcohol (ethyl alcohol or ethanol) is rapidly absorbed in the stomach and is transported to the liver and metabolized by 2 pathways. The primary metabolic pathway contributes to the excess synthesis of triglycerides, a phenomenon that is responsible for producing a fatty liver, even in those who are well nourished. Engorgement of hepatocytes with fat causes necrosis, triggering an inflammatory process (alcoholic hepatitis), which is later followed by fibrosis, the hallmark of cirrhosis. Early hepatic involvement may result in elevation in γ-glutamyl transpeptidase and serum glutamic-pyruvic transaminase. The second metabolic pathway, which is utilized at high serum alcohol levels, involves the microsomal enzyme system of the liver, in which the cofactor is reduced nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate. The net effect of activation of this pathway is to decrease metabolism of drugs that share this system and to allow for their accumulation, enhanced effect, and possible toxicity.

Clinical Manifestations

Alcohol acts primarily as a central nervous system depressant. It produces euphoria, grogginess, talkativeness, impaired short-term memory, and an increased pain threshold. Alcohol’s ability to produce vasodilation and hypothermia is also centrally mediated. At very high serum levels, respiratory depression occurs. Its inhibitory effect on pituitary antidiuretic hormone release is responsible for its diuretic effect. The gastrointestinal complications of alcohol use can occur from a single large ingestion. The most common is acute erosive gastritis, which is manifested by epigastric pain, anorexia, vomiting, and heme-positive stools. Less commonly, vomiting and midabdominal pain may be caused by acute alcoholic pancreatitis; diagnosis is confirmed by the finding of elevated serum amylase and lipase levels.

Diagnosis

Primary care settings provide opportunity to screen teens for alcohol use or problem behaviors. Brief alcohol screening instruments (CRAFFT [see Table 108-7] or AUDIT [Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, Table 108-12]) perform well in a clinical setting as techniques to identify Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV)–defined adolescents with alcohol use disorders (Table 108-13). A score of ≥8 on the AUDIT questionnaire identifies people who drink excessively and who would benefit from reducing or ceasing drinking (see Table 108-12). Teenagers in the early phases of alcohol use exhibit few physical findings. Recent use of alcohol may be reflected in elevated gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and amino transferase (AST).

Table 108-12 ALCOHOL USE DISORDERS IDENTIFICATION TEST (AUDIT)

| SCORE (0-4)* | |

|---|---|

| 1. How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? | Never (0) to more than four per week (4) |

| 2. How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day? | One or two (0) to more than ten (4) |

| 3. How often do you have six or more drinks on one occasion? | Never (0) to daily or almost daily (4) |

| 4. How often during the last year have you found that you were not able to stop drinking once you had started? | Never (0) to daily or almost daily (4) |

| 5. How often during the last year have you failed to do what was normally expected from you because of drinking? | Never (0) to daily or almost daily (4) |

| 6. How often during the last year have you needed a first drink in the morning to get yourself going after a heavy drinking session? | Never (0) to daily or almost daily (4) |

| 7. How often during the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking? | Never (0) to daily or almost daily (4) |

| 8. How often during the last year have you been unable to remember what happened the night before because you had been drinking? | Never (0) to daily or almost daily (4) |

| 9. Have you or someone else been injured as a result of your drinking? | No (0) to yes, during the last year (4) |

| 10. Has a relative, friend, doctor or other health worker been concerned about your drinking or suggested that you should cut down? | No (0) to yes, during the last year (4) |

* Score ≥8 = problem drinking.

From Schuckit MA: Alcohol-use disorders, Lancet 373:492–500, 2009, Table 1.

Table 108-13 CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF ALCOHOL DEPENDENCE, ACCORDING TO DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL (DSM-IV) AND INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF DISEASES (ICD-10)

DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL (DSM-IV)

INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF DISEASES (ICD-10)

In acute care settings, the alcohol overdose syndrome should be suspected in any teenager who appears disoriented, lethargic, or comatose. Although the distinctive aroma of alcohol may assist in diagnosis, confirmation by analysis of blood is recommended. At levels >200 mg/dL, the adolescent is at risk of death, and levels >500 mg/dL (median lethal dose) are usually associated with a fatal outcome. When the level of obtundation appears excessive for the reported blood alcohol level, head trauma, hypoglycemia, or ingestion of other drugs should be considered as possible confounding factors.

Treatment

The usual mechanism of death from the alcohol overdose syndrome is respiratory depression, and artificial ventilatory support must be provided until the liver can eliminate sufficient amounts of alcohol from the body. In a patient without alcoholism, it generally takes 20 hr to reduce the blood level of alcohol from 400 mg/dL to zero. Dialysis should be considered when the blood level is >400 mg/dL. As a follow-up to acute treatment, referral for treatment of the alcohol use disorder is indicated. Group counseling, individualized counseling, and multifamily educational intervention have been found to be quite effective interventions for teens.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Substance Abuse. Policy statement—alcohol use by youth and adolescents: a pediatric concern. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1078-1087.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol use among high school students—Georgia, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:885-889.

Howland J, Rohsenow DJ, Arnedt JT, et al. The acute effects of caffeinated versus non-caffeinated alcoholic beverage on driving performance and attention/reaction time. Addiction. 2010;106:335-341.

Kriston L, Hölzel L, Weiser AK, et al. Meta-analysis: are 3 questions enough to detect unhealthy alcohol use? Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:879-888.

McArdle P. Alcohol abuse in adolescents. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:524-527.

McArdle P. Use and misuse of drugs and alcohol in adolescence. BMJ. 2008;337:46-50.

McCambridge J, McAlaney J, Rowe R. Adult consequences of late adolescent alcohol consumption: a systematic review of cohort studies. PLos Med. 2011;8(2):e100413.

Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:492-500.

Tyler KA. Examining the changing influence of predictors on adolescent alcohol misuse. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2007;16:95-114.

Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents. JAMA. 2010;304(5):527-535.

108.2 Tobacco

Cigarettes

Nearly 5 million persons die annually from smoking across the globe; the number of deaths is roughly equal between developing nations and industrialized nations. Compared to all other substances and firearms, tobacco kills more individuals in the USA each yr than all these other causes combined. The average smoker in the USA starts at age 12 yr, and most are regular smokers by age 14 yr. More than 90% of adolescent smokers become adult smokers. Factors associated with youth tobacco use include exposure to smokers (friends, parents), availability of tobacco, low socioeconomic status, poor school performance, low self-esteem, lack of perceived risk of use, and lack of skills to resist influences to tobacco use.

Current smoking rates among high school students have trended downward over the last decade for lifetime cigarette use (from 20.0% to 12.4%) and current frequent cigarette use (from 16.8% to 8.1%). Overall, more whites report current tobacco use (29.9%) than Hispanics (20.1%) or blacks (16.0%). Clove cigarettes (kreteks) and flavored cigarettes (bidis) are popular with younger students. Both types of flavored cigarettes contain tobacco with other additives and deliver more nicotine and other harmful substances because they are unfiltered. Cigar or mini-cigar (cigarillo) use is reported most frequently by older male students (26.2%). Tobacco use is linked to other high risk behaviors. Teens who smoke are more likely than nonsmokers to use alcohol and engage in unprotected sex, are 8 times more likely to use marijuana, and are 22 times more likely to use cocaine.

Tobacco is used by teens in all regions of the world, although the form of tobacco used differs. In the Americas and Europe, cigarette smoking prevalence is higher than other tobacco use, although cigars and smokeless tobacco are also used; in the Eastern Mediterranean, shisha (flavored tobacco smoked in hookah pipes) is prevalent; in Southeast Asia, smokeless tobacco products are used; in the Western Pacific, betel nut is chewed with tobacco; and pipe, snuff, and rolled tobacco leaves are used in Africa.

Pharmacology

Nicotine, the primary active ingredient in cigarettes, is addictive. Nicotine is absorbed by multiple sites in the body, including the lungs, skin, gastrointestinal tract, and buccal and nasal mucosa. The action of nicotine is mediated through nicotinic acetylcholine receptors located on noncholinergic presynaptic and postsynaptic sites in the brain and causes increased levels of dopamine. Nicotine also stimulates the adrenal glands to release epinephrine, causing an immediate elevation in blood pressure, respiration and heart rate. The average nicotine content of 1 cigarette is 10 mg and the average nicotine intake per cigarette ranges from 1.0 to 3 mg. Nicotine, as delivered in cigarette smoke, has a half-life of about 2 hr. Cotinine is the major metabolite of nicotine via C-oxidation. It has a biologic half-life of 19-24 hr and can be detected in urine, serum, and saliva.

Clinical Manifestations

Adverse health effects from regular smoking include an increased prevalence of chronic cough, sputum production, and wheezing. Smoking during pregnancy is associated with an average decrease in fetal weight of 200 g; this decrease, added to the already smaller size of infants born to teenagers, increases perinatal morbidity and mortality. Tobacco smoke induces hepatic smooth endoplasmic reticulum enzymes and, as a result, may also influence metabolism of drugs such as phenacetin, theophylline, and imipramine. Withdrawal symptoms can occur when adolescents try to quit. Irritability, decreased concentration, increased appetite, and strong cravings for tobacco are common withdrawal symptoms. Nicotine dependence is defined in Table 108-14.

Table 108-14 CHARACTERISTICS OF NICOTINE DEPENDENCE BASED ON THE DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL VERSION IV (DSM-IV) AND THE INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF DISEASES REVISION 10 (ICD-10)

DSM-IV CRITERIA

ICD-10 CRITERIA

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

Treatment

The approach to smoking cessation in adolescents includes the 5 A’s (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange) and use of nicotine replacement therapy in addicted teens who are motivated to quit and are not using smokeless tobacco (SLT). Consensus panels recommend the 5 A’s although evidence of efficacy in adolescents is limited. Nicotine patch studies to date in adolescents suggest a positive effect on reducing withdrawal symptoms and that pharmacotherapy should be combined with behavioral therapy to reach higher cessation and lower relapse rates. Nicotine is also available as a gum, inhaler, nasal spray, lozenge, or microtab. Medications such as bupropion are not approved for use under 18 yr old; some pilot studies in adolescents report cessation efficacy with 150 mg or 300 mg of bupropion daily. Varenicline has successfully been used in adults but may be associated with a risk of suicide. Additional options may be available through formal smoking cessation programs offered by community agencies.

Smokeless Tobacco

Surveys in the late 1980s and 1990s indicating the increased use of SLT prompted the National Cancer Institute to lead the U.S. federal government’s effort to prevent SLT use, especially in adolescents. Surveys indicate that from the early to mid 1990s to 2008, lifetime prevalence of SLT use continues to decline in 8th, 10th, and 12th graders. It remains more popular with boys than girls (13.4% versus 2.3%). While it is less lethal, SLT carries risks of addiction and oral problems such as receding gums/gingivitis and precancerous leukoplakia.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committees on Environmental Health, Substance Abuse, Adolescence, Native American Child Care. Policy statement–tobacco use: a pediatric disease. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1474-1487.

Becklake MR, Ghezzo H, Ernst P. Childhood predictors of smoking in adolescence: a follow-up study of Montreal schoolchildren. CMAJ. 2005;173:377-379.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2006 national youth tobacco survey and key prevalence indicators. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/pdfs/indicators.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2011

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette use among high school students—Unites States, 1991–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:686-688.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Changes in tobacco use among youths aged 13–15 years—Panama, 2002 and 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;57:1416-1419.

Hatsukami D, Stead LF, Gupta PC. Tobacco addiction. Lancet. 2008;371:2027-2038.

Martinasek MP, McDermott RJ, Martini L. Waterpipe (hookah) tobacco smoking among youth. Curr Prob Pediatric Adolesc Med. 2011;41(2):33-58.

Muramoto M, Leischow S, Sherrill D, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 2 dosages of sustained-release bupropion for adolescent smoking cessation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:1067-1074.

Pollock JD, Koustova E, Hoffman A, et al. Treatments for nicotine addiction should be a top priority. Lancet. 2009;374:513-514.

108.3 Marijuana

Marijuana (THC, “pot,” “weed,” “hash,” “grass”), derived from the Cannabis sativa hemp plant, is the most commonly abused illicit drug. The main active chemical, tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), is responsible for its hallucinogenic properties. THC is absorbed rapidly by the nasal or oral routes, producing a peak of subjective effect at 10 min and 1 hr, respectively. Marijuana is generally smoked as a cigarette (“reefer” or “joint”) or in a pipe. Although there is much variation in content, each cigarette contains 8-10% THC. Another popular form that is smoked, a “blunt,” is a hollowed-out small cigar refilled with marijuana. Hashish is the concentrated THC resin in a sticky black liquid or oil. While marijuana use by teens has declined in the last decade, 32.4% of U.S. high school seniors report past-year use; 19% of European students reported use of marijuana at least once during their lifetime. Worldwide, including sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, it represents the majority of illicit drug use by youth.

Clinical Manifestations

In addition to the “desired” effects of elation and euphoria, marijuana may cause impairment of short-term memory, poor performance of tasks requiring divided attention (e.g., those involved in driving), loss of critical judgment, decreased coordination, and distortion of time perception (Table 108-15). Visual hallucinations and perceived body distortions occur rarely, but there may be “flashbacks” or recall of frightening hallucinations experienced under marijuana’s influence that usually occur during stress or with fever.

Table 108-15 ACUTE AND CHRONIC ADVERSE EFFECTS OF CANNABIS USE

ACUTE ADVERSE EFFECTS

CHRONIC ADVERSE EFFECTS

From Hall W, Degenhardt L: Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use, Lancet 374:1383–1390, 2009.

Smoking marijuana for a minimum of 4 days/wk for 6 mo appears to result in dose-related suppression of plasma testosterone levels and spermatogenesis, prompting concern about the potential deleterious effect of smoking marijuana before completion of pubertal growth and development. There is an antiemetic effect of oral THC or smoked marijuana, often followed by appetite stimulation, which is the basis of the drug’s use in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. Although the possibility of teratogenicity has been raised because of findings in animals, there is no evidence of such effects in humans. An amotivational syndrome has been described in long-term marijuana users who lose interest in age-appropriate behavior, yet proof of the causative relationship remains equivocal. Chronic use is associated with increased anxiety and depression, learning problems, poor job performance, and respiratory problems such as pharyngitis, sinusitis, bronchitis, and asthma (see Table 108-15).

The increased THC content of marijuana of 5- to 15-fold in the 1990s, as compared to the 1970s, is related to the observation of a withdrawal syndrome, occurring 24 to 48 hr after discontinuing the drug. Heavy users experience malaise, irritability, agitation, insomnia, drug craving, shakiness, diaphoresis, night sweats, and gastrointestinal disturbance. The symptoms peak by the 4th day, and they resolve in 10-14 days. Certain drugs may interact with marijuana to potentiate sedation (alcohol, diazepam), potentiate stimulation (cocaine, amphetamines), or be antagonistic (propranolol, phenytoin).

Behavioral interventions, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and motivational incentives, have shown to be effective in treating marijuana dependency.

Aldington S, Williams M, Nowitz M, et al. Effects of cannabis on pulmonary structure, function and symptoms. Thorax. 2007;62:1058-1063.

Bottorff JL, Johnson JL, Moffat BM, et al. Relief oriented use of marijuana by teens. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2009;4:7.

Brook JS, Zhang C, Brook DW. Developmental trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(11):55-60.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Inadvertent ingestion of marijuana—Los Angeles, California, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:947-950.

Di Forti M, Morgan C, Dazzan P, et al. High-potency cannabis and the risk of psychosis. Br J Psych. 2009;195:488-491.

Hall W. Is cannabis use psychogenic? Lancet. 2006;367:193-194.

Hall W, Degenhardt L. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet. 2009;374:1383-1390.

Nordentoft M, Hjorthøj C. Cannabis use and risk of psychosis in later life. Lancet. 2007;370:293-294.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. The NSDUH report: marijuana use and perceived risk of use among adolescents 2002 to 2007. Rockville, MD. 2009.

108.4 Inhalants

Inhalants, found in many common household products, comprise a diverse group of volatile substances whose vapors can be inhaled to produce psychoactive effects. The practice of inhalation is popular among younger adolescents and decreases with age. Young adolescents are attracted to these substances because of their rapid action, easy availability, and low cost. Products that are abused as inhalants include volatile solvents (paint thinners, glue), aerosols (spray paint, hair spray), gases (propane tanks, lighter fluid), and nitrites (“poppers” or “video head cleaner”). The most popular inhalants among young adolescents are glue, shoe polish, and spray paint. The various products contain a wide range of chemicals with serious adverse health effects (Table 108-16). Huffing, the practice of inhaling fumes can be accomplished using a paper bag containing a chemical-soaked cloth, spraying aerosols directly into the nose/mouth, or using a balloon, plastic bag, or soda can filled with fumes. The percentage of adolescents using inhalants continues to decline, with 3.9% of high school students reported having used inhalants in the preceding 30-day period (2008); 9% of European youth reported ever using inhalants. Inhalant use has been high among Native American youth perhaps resulting from isolation and lower educational levels; Eskimo youth living in 14 isolated villages in the Bering Strait reported a lifetime of inhalant use of 48%.

Table 108-16 HAZARDS OF CHEMICALS FOUND IN COMMONLY ABUSED INHALANTS

Amyl nitrite, butyl nitrite (“poppers,” “video head cleaner”): sudden sniffing death syndrome, suppressed immunologic function, injury to red blood cells (interfering with oxygen supply to vital tissues)

Benzene (found in gasoline): bone marrow injury, impaired immunologic function, increased risk of leukemia, reproductive system toxicity

Butane, propane (found in lighter fluid, hair and paint sprays): sudden sniffing death syndrome via cardiac effects, serious burn injuries (because of flammability)

Freon (used as a refrigerant and aerosol propellant): sudden sniffing death syndrome, respiratory obstruction and death (from sudden cooling/cold injury to airways), liver damage

Methylene chloride (found in paint thinners and removers, degreasers): reduction of oxygen-carrying of blood, changes to the heart muscle and heartbeat

Nitrous oxide (“laughing gas”), hexane: death from lack of oxygen to the brain, altered perception and motor coordination, loss of sensation, limb spasms, blackouts caused by blood pressure changes, depression of heart muscle functioning

Toluene (found in gasoline, paint thinners and removers, correction fluid): brain damage (loss of brain tissue mass, impaired cognition, gait disturbance, loss of coordination, loss of equilibrium, limb spasms, hearing and vision loss), liver and kidney damage

Trichlorethylene (found in spot removers, degreasers): sudden sniffing death syndrome, cirrhosis of the liver, reproductive complications, hearing and vision damage

Clinical Manifestations

The major effects of inhalants are psychoactive (Table 108-17). The intoxication lasts only a few minutes, so a typical user will huff repeatedly over an extended period of time (hours) in order to maintain the high. The immediate effects of inhalants are similar to alcohol: euphoria, slurred speech, decreased coordination, and dizziness. Toluene, the main ingredient in model airplane glue and some rubber cements, causes relaxation and pleasant hallucinations for up to 2 hr. Euphoria is followed by violent excitement or coma may result from prolonged or rapid inhalation. Volatile nitrites, such as amyl nitrite, butyl nitrite, and related compounds marketed as room deodorizers, are used as euphoriants, enhancers of musical appreciation, and sexual enhancements among older adolescents and young adults. They may result in headaches, syncope, and lightheadedness; profound hypotension and cutaneous flushing followed by vasoconstriction and tachycardia; transiently inverted T waves and depressed ST segments on electrocardiography; methemoglobinemia; increased bronchial irritation; and increased intraocular pressure.

Table 108-17 STAGES IN SYMPTOM DEVELOPMENT

| STAGE | SYMPTOMS |

|---|---|

| 1: Excitatory | Euphoria, excitation, exhilaration, dizziness, hallucinations, sneezing, coughing, excess salivation, intolerance to light, nausea and vomiting, flushed skin and bizarre behavior |

| 2: Early CNS depression | Confusion, disorientation, dullness, loss of self-control, ringing or buzzing in the head, blurred or double vision, cramps, headache, insensitivity to pain, and pallor or paleness |

| 3: Medium CNS depression | Drowsiness, muscular uncoordination, slurred speech, depressed reflexes, and nystagmus or rapid involuntary oscillation of the eyeballs |

| 4: Late CNS depression | Unconsciousness that may be accompanied by bizarre dreams, epileptiform seizures, and EEG changes |

CNS, central nervous system; EEG, electroencephalogram.

From Harris D: Volatile substance abuse, Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 91:ep93-ep100, 2006, Table 1.

Complications

Model airplane glue is responsible for a wide range of complications, related to chemical toxicity, to the method of administration (in plastic bags, with resultant suffocation), and to the often dangerous setting in which the inhalation occurs (inner-city roof tops). Common neuromuscular changes reported in chronic inhalant abusers include difficulty coordinating movement, gait disorders, muscle tremors, and spasticity, particularly in the legs (Table 108-18). Moreover, chronic use may cause pulmonary hypertension, restrictive lung defects or reduced diffusion capacity, peripheral neuropathy, hematuria, tubular acidosis, and possibly cerebral and cerebellar atrophy. Chronic inhalant abuse has long been linked to widespread brain damage and cognitive abnormalities that can range from mild impairment (poor memory, decreased learning ability) to severe dementia. Death in the acute phase may result from cerebral or pulmonary edema or myocardial involvement (see Table 108-18).

Table 108-18 DOCUMENTED CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS OF VOLATILE SUBSTANCE ABUSE (VSA)

| CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS OF ACUTE AND CHRONIC VSA | |

| Ventricular fibrillation | Muscle weakness |

| Asystolic cardiac arrest | Abdominal pain |

| Myocardial infarction | Cough |

| Ataxia | Aspiration pneumonia |

| Agitation | Chemical pneumonitis |

| Limb and trunk uncoordination | Coma |

| Tremor | Visual and auditory hallucinations |

| Visual loss | Acute delusions |

| Tinnitus | Nausea and vomiting |

| Dysarthria | Pulmonary edema |

| Vertigo | Photophobia |

| Hyperreflexia | Rash |

| Acute confusional state | Jaundice |

| Conjunctivitis | Anorexia |

| Acute paranoia | Slurred speech |

| Depression | Diarrhea |

| Oral and nasal mucosal ulceration | Weight loss |

| Halitosis | Epistaxis |

| Convulsions/fits | Rhinitis |

| Headache | Cerebral edema |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Visual loss |

| Methemoglobinemia | Burns |

| Acute trauma | Renal tubular acidosis |

From Harris D: Volatile substance abuse, Arch Dis Child Edu Pract Ed 91:ep93-ep100, 2006, Table 2.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of inhalants is difficult because of the ubiquitous nature of the products and decreased parental awareness of their dangers. In the primary care setting, providers need to enquire of parents if they have witnessed any unusual behaviors in their teen; noticed high-risk products in their bedrooms; seen paint on the teen’s hands, nose, or mouth; or found paint coated or chemical coated rags. Complete blood counts, coagulation studies, and hepatic and renal function studies may identify the complications. In extreme intoxication, a user may manifest symptoms of restlessness, general muscle weakness, dysarthria, nystagmus, disruptive behavior, and occasionally hallucinations. Toluene is excreted rapidly in the urine as hippuric acid, with the residual detectable in the serum by gas chromatography.

Treatment

Treatment is generally supportive and directed toward control of arrhythmia and stabilization of respirations and circulation. Withdrawal symptoms do not usually occur.

Harris D. Volatile substance abuse. Arch Dis Child Edu Pract Ed. 2006;91:ep93-ep100.

Marsolek MR, White NC, Litovitz TL. Inhalent abuse: monitoring trends by using poison control data, 1993–2008. Pediatrics. 2010;125:906-913.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA infofacts: inhalants. website www.nida.nih.gov/infofacts/inhalants.html Accessed April 21, 2010

National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Adolescent inhalant use and selected respiratory conditions. http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k10/175/175RespiratoryCondHTML.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2011

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. The NSDUH report: trends in adolescent inhalant use: 2002 to 2007. Rockville, MD. 2009.

Williams JF, Storck M, Committee on Substance Abuse and Committee on Native American Child Health Inhalant Abuse. Inhalant abuse. Pediatrics. 2007;119:1009-1017.

108.5 Hallucinogens

Several naturally occurring and synthetic substances are used by adolescents for their hallucinogenic properties. They have chemical structures similar to neurotransmitters such as serotonin, yet their exact mechanism of action remains unclear. Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) or Ecstasy are the most commonly reported hallucinogens used.

Lysergic Acid Diethylamide

LSD (acid, big “d,” blotters) is a very potent hallucinogen that is made from lysergic acid found in ergot, a fungus that grows on rye and other grains. Its high potency allows effective doses to be applied to absorbent paper, or it can be taken as a liquid or a tablet. The onset of action can be between 30 and 60 min, and it peaks between 2 and 4 hr. By 10-12 hr, an individual returns to the predrug state. Four percent of U.S. 12th graders report trying LSD at least once.

Clinical Manifestations

The effects of LSD can be divided into 3 categories: somatic (physical effects), perceptual (altered changes in vision and hearing), and psychic effects (changes in sensorium). The common somatic symptoms are dizziness, dilated pupils, nausea, flushing, elevated temperature, and tachycardia. The sensation of synesthesia, or “seeing” smells and “hearing” colors, as well as major distortions of time and self have been reported with high doses of LSD. Delusional ideation, body distortion, and suspiciousness to the point of toxic psychosis are the more serious of the psychic symptoms. LSD is not considered to be an addictive drug since it does not typically produce drug-seeking behavior.

Treatment

An individual is considered to have a “bad trip” when the sensory experiences causes the user to become terrified or panicked. These episodes should be treated by removing the individual from the aggravating situation and placing him in a quiet room with a calming friend. In situations of extreme agitation or seizures, use of benzodiazepines may be warranted. “Flashbacks” or LSD-induced states after the drug has worn off and tolerance to the effects of the drug are additional complications of its use.

Methylenedioxymethamphetamine

MDMA (“X,” Ecstasy), a phenylisopropylamine hallucinogen, is a synthetic compound similar to hallucinogenic mescaline and the stimulant methamphetamine. Like other hallucinogens, this drug is proposed to interact with serotoninergic neurons in the central nervous system (CNS). It is the preferred drug at “raves,” all-night dance parties, and is also known as one of the “club drugs” along with γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) and ketamine (see Table 108-5). Between 2005 and 2008, past-year use of MDMA increased among both 10th and 12th graders. Six percent of 12th graders report having tried MDMA at least once. Similar increases were seen among European youth; the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs reported that in 2007, 3% of European students report having tried ecstasy during their lifetime, with 5 countries reporting ever-use rates of 6-7%.

Clinical Manifestations

Euphoria, a heightened sensual awareness, and increased psychic and emotional energy are acute effects. Compared to other hallucinogens, MDMA is less likely to produce emotional lability, depersonalization, and disturbances of thought. Nausea, jaw clenching, teeth grinding, and blurred vision are somatic symptoms, whereas anxiety, panic attacks, and psychosis are the adverse psychiatric outcomes. A few deaths have been reported after ingestion of the drug. In high doses, MDMA can interfere with the body’s ability to regulate temperature. The resultant hyperthermia in association with vigorous dancing at a “rave” has resulted in severe liver, kidney, and cardiovascular system failure and death. There are no specific treatment regimens recommended for acute toxicity. Chronic MDMA use can lead to changes in brain function, affecting cognitive tasks and memory. These symptoms may occur because of MDMA’s effects on neurons that use serotonin as a neurotransmitter. The serotonin system plays an important role in regulating mood, aggression, sexual activity, sleep, and sensitivity to pain. A high rate of dependence has been found among MDMA users. MDMA exposure may be associated with long-term neurotoxicity and damage to serotonin-containing neurons. In nonhuman primates, exposure to MDMA for only 4 days caused damage to serotonin nerve terminals that was evident 6-7 yr later. There are no specific pharmacologic treatments for MDMA addiction. Drug abuse recovery groups are recommended.

Phencyclidine

Phencyclidine (PCP) (sternyl, angel dust, “hog,” “peace pill,” “sheets”) is an arylcyclohexalamine whose popularity is related, in part, to its ease of synthesis in home laboratories. One of the by-products of home synthesis causes cramps, diarrhea, and hematemesis. It is a “dissociative drug” that produces feelings of detachment from the surrounding environment and self. The drug is thought to potentiate adrenergic effects by inhibiting neuronal reuptake of catecholamines. PCP is available as a tablet, liquid, or powder, which may be used alone or sprinkled on cigarettes (“joints”). The powders and tablets generally contain 2-6 mg of PCP, whereas joints average 1 mg for every 150 mg of tobacco leaves, or approximately 30-50 mg per joint.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations are dose related and produce alterations of perception, behavior, and autonomic functions. Euphoria, nystagmus, ataxia, and emotional lability occur within 2-3 min after smoking 1-5 mg and last for 4-6 hr. At these low doses the user is likely to experience shallow breathing, flushing, generalized numbness of extremities, and loss of motor coordination. Hallucinations may involve bizarre distortions of body image that often precipitate panic reactions. With doses of 5-15 mg, a toxic psychosis may occur, with disorientation, hypersalivation, and abusive language lasting for >1 hr. Hypotension, generalized seizures, and cardiac arrhythmias commonly occur with plasma concentrations from 40-200 mg/dL. Death has been reported during psychotic delirium, from hypertension, hypotension, hypothermia, seizures, and trauma. The coma of PCP may be distinguished from that of the opiates by the absence of respiratory depression; the presence of muscle rigidity, hyperreflexia, and nystagmus; and lack of response to naloxone. PCP psychosis may be difficult to distinguish from schizophrenia. In the absence of a history of use, analysis of urine must be depended on for diagnosis.

Treatment

Management of the PCP-intoxicated patient includes placement in a darkened, quiet room on a floor pad, safe from injury. Acute alcohol intoxication may be present also. For recent oral ingestion, gastric absorption is poor and induction of emesis or gastric lavage is useful. Diazepam, in a dose of 5-10 mg orally or 2-5 mg intravenously, may be helpful if the patient is agitated and not comatose. Rapid excretion of the drug is promoted by acidification of the urine. Supportive therapy of the comatose patient is indicated with particular attention to hydration, which may be compromised by PCP-induced diuresis. Inpatient and/or behavioral treatments can be helpful for chronic PCP users.

Bryner JK, Wang UK, Hui JW, et al. Dextromethorphan abuse in adolescence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:1217-1222.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ecstasy overdoses at a New Year’s eve rave—Los Angeles, CA, 2010. MMWR. 2010;59(22):677-680.

Halpern JH, Sherwood AR, Hudson JI, et al. Residual neurocognitive features of long-term ecstasy users with minimal exposure to other drugs. Addiction. 2010;106:777-786.

Hysek CM, Vollenweider FX, Liechti ME. Effects of a β-blocker on the cardiovascular response to MDMA (Ecstacy). Emerg Med J. 2010;27:586-589.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA infofacts: club drugs (GHB, ketamine, and rohypnol). (website) www.nida.nih.gov/infofacts/Clubdrugs.html Accessed April 21, 2010

Poikolainen K. Ecstasy and the antecedents of illicit drug use. BMJ. 2006;332:803-804.

Ricaurte GA, McCann UD. Recognition and management of complications of new recreational drug use. Lancet. 2005;365:2137-2145.

Snead OCIII, Gibson KM. γ-Hydroxybutyric acid. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2721-2732.

108.6 Cocaine

Cocaine, an alkaloid extracted from the leaves of the South American Erythroxylon coca, is supplied as the hydrochloride salt in crystalline form. With “snorting” it is rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream from the nasal mucosa, detoxified by the liver, and excreted in the urine as benzoylecgonine. Smoking the cocaine alkaloid (“freebasing”) involves inhaling the cocaine vapors in pipes, or cigarettes mixed with tobacco or marijuana. Accidental burns are potential complications of this practice. With crack cocaine, the crystallized rock form, the smoker feels “high” in <10 sec. The risk of addiction with this method is higher and more rapidly progressive than from snorting cocaine. Tolerance develops and the user must increase the dose or change the route of administration, or both, to achieve the same effect. In order to sustain the high, cocaine users repeatedly use cocaine in short periods of time known as “binges.” Drug dealers often place cocaine in plastic bags or condoms and swallow these containers during transport. Rupture of a container produces a sympathomimetic crisis (see Table 108-6). Cocaine use among high school students has remained unchanged in the last decade, with 7.2% of 12th graders having tried the drug (any route) at least once. Average use rates are somewhat lower among European students.

Clinical Manifestations

Cocaine is a strong central nervous system stimulant that increases dopamine levels by preventing reuptake. Cocaine produces euphoria, increased motor activity, decreased fatigability, and mental alertness. Its sympathomimetic properties are responsible for pupillary dilatation, tachycardia, hypertension, and hyperthermia. Snorting cocaine chronically results in loss of sense of smell, nosebleeds, and chronic rhinorrhea. Injecting cocaine increases risk for HIV infection. Chronic abusers experience anxiety, irritability, and sometimes paranoid psychosis. Lethal effects are possible, especially when cocaine is used in combination with other drugs, such as heroin, in an injectable form known as a “speedball.” Cocaine, when taken with alcohol, is metabolized by the liver to produce cocaethylene, a substance that enhances the euphoria and is associated with a greater risk of sudden death than cocaine alone. Pregnant adolescents who use cocaine place their fetus at risk of premature delivery, complications of low birthweight, and possibly developmental disorders.

Treatment

There are no FDA-approved medications for treatment of cocaine addiction. Cognitive-behavioral therapy has been shown to be effective when provided in combination with additional services and social support.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syringe exchange programs—United States, 2008. MMWR. 2010;59(45):1488-1492.

Kerr T, Montaner JSG, Wood E. Sciences and politics of heroin prescription. Lancet. 2010;375:1849-1850.

Marsden J, Eastwood B, Bradbury C, et al. Effectiveness of community treatments for heroin and crack cocaine addiction in England: a prospective, in-treatment cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1262-1270.

Starrels JL, Becker WC, Alford DP, et al. Systematic review: treatment agreements and urine drug testing to reduce opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:712-720.

108.7 Amphetamines

Stimulants, particularly amphetamines, are among the most frequently reported illicit drugs, other than marijuana used by high school seniors. Methamphetamine, commonly known as “ice,” accounted for >25% of stimulant use. Methamphetamine, a nervous system stimulant and schedule II drug, has a high potential for abuse. Most of the methamphetamine currently abused is produced in illegal laboratories. It is a white, odorless, bitter tasting powder that is particularly popular among adolescents and young adults because of its potency and ease of absorption. It can be ingested orally, by smoking, needle injection, or absorption across mucous membranes. Amphetamines have multiple CNS effects, among them the release of neurotransmitters and an indirect catecholamine agonist effect. In recent years there has been a general decline of methamphetamine use among high school students. In the 2008 Monitoring the Future Study, 2.8% of 12th graders report using methamphetamine at least once. In the 2007 European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs, 3% of European students reported lifetime use of amphetamines.

Clinical Manifestations

Methamphetamine rapidly increases the release and blocks the reuptake of dopamine, a powerful “feel good” neurotransmitter (Table 108-19). The effects of amphetamines can be dose related. In small amounts amphetamine effects resemble other stimulants: increased physical activity, rapid and/or irregular heart rate, increased blood pressure and decreased appetite. High doses produce slowing of cardiac conduction in the face of ventricular irritability. Hypertensive and hyperpyrexic episodes can occur as seizures (see Table 108-6). Binge effects result in the development of psychotic ideation with the potential for sudden violence. Cerebrovascular damage, psychosis, severe receding of the gums with tooth decay, and infection with HIV and hepatitis B and C can result from long-term use. There is a withdrawal syndrome associated with amphetamine use, with early, intermediate, and late phases. The early phase is characterized as a “crash” phase with depression, agitation, fatigue, and desire for more of the drug. Loss of physical and mental energy, limited interest in the environment, and anhedonia mark the intermediate phase. In the final phase, drug craving returns, often triggered by particular situations or objects.

Treatment

Acute agitation and delusional behaviors can be treated with haloperidol or droperidol. Phenothiazines are contraindicated and may cause a rapid drop in blood pressure or seizure activity. Other supportive treatment consists of a cooling blanket for hyperthermia and treatment of the hypertension and arrhythmias, which may respond to sedation with lorazepam or diazepam. For the chronic user, comprehensive cognitive-behavioral interventions have been shown to effective treatment options.

Setlik J, Bond R, Ho M. Adolescent prescription ADHA medication abuse is rising along with prescriptions for these medications. Pediatrics. 2009;124:875-880.

Spoth RL, Clair S, Shin C, et al. Long-term effects of universal preventive interventions on methamphetamine use among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:876-882.

108.8 Opiates

Heroin is a highly addictive synthetic opiate drug made from a naturally occurring substance (morphine) in the opium poppy plant. It is a white or brown powder that can be injected (intravenously or subcutaneously), snorted/sniffed, or smoked. Intravenous injection produces an immediate effect, whereas effects from the subcutaneous route occur in minutes, and from snorting, 30 minutes. After injection, heroin crosses the blood-brain barrier, is converted to morphine, and binds to opiate receptors. Tolerance develops to the euphoric effect, and the chronic user must use more heroin to achieve the same intense effect. Heroin use among teens peaked in the mid-1990s but is resurgent in some suburban communities, as is the use of prescription opioids found in the home. Approximately 1.5% of high school seniors report having tried heroin at least once; similar rates are reported among European students.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations are determined by the purity of the heroin or its adulterants, combined with the route of administration. The immediate effects include euphoria, diminution in pain, flushing of the skin, and pinpoint pupils (Table 108-19). An effect on the hypothalamus is suggested by the lowering of body temperature. The most common dermatologic lesions are the “tracks,” the hypertrophic linear scars that follow the course of large veins. Smaller, discrete peripheral scars, resembling healed insect bites, may be easily overlooked. The adolescent who injects heroin subcutaneously may have fat necrosis, lipodystrophy, and atrophy over portions of the extremities. Attempts to conceal these stigmata may include amateur tattoos in unusual sites. Skin abscesses secondary to unsterile techniques of drug administration are commonly found. There is a loss of libido; the mechanism is unknown. The chronic heroin user may resort to prostitution to support the habit, thus increasing the risk of sexually transmitted diseases (including HIV), pregnancy, and other infectious diseases. Constipation results from decreased smooth muscle propulsive contractions and increased anal sphincter tone. The absence of sterile technique in injection may lead to cerebral microabscesses or endocarditis, usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Abnormal serologic reactions are also common, including false-positive Venereal Disease Research Laboratory and latex fixation tests.

Withdrawal

After a period of ≥8 hr without heroin, the addicted individual undergoes, during a 24-36 hr period, a series of physiologic disturbances referred to collectively as “withdrawal” or the abstinence syndrome (see Table 108-19). The earliest sign is yawning, followed by lacrimation, mydriasis, restlessness, insomnia, “goose flesh,” cramping of the voluntary musculature, bone pain, hyperactive bowel sounds and diarrhea, tachycardia, and systolic hypertension. While the administration of methadone has been the most common method of detoxification, the addition of buprenorphine, an opiate agonist-antagonist, is available for detoxification and maintenance treatment of heroin and other opiates. This medication has the advantage in that it offers less risk of addiction and overdose, and withdrawal effects and can be dispensed in the privacy of a physician’s office. Combined with behavioral interventions, it has a greater success rate of detoxification. A combination drug, buprenorphine/naloxone has been formulated to minimize abuse during detoxification.

Overdose Syndrome

The overdose syndrome is an acute reaction after the administration of an opiate. It is the leading cause of death among drug users. The clinical signs include stupor or coma, seizures, miotic pupils (unless severe anoxia has occurred), respiratory depression, cyanosis, and pulmonary edema. The differential diagnosis includes CNS trauma, diabetic coma, hepatic (and other) encephalopathy, Reye syndrome, as well as overdose of alcohol, barbiturates, PCP, or methadone. Diagnosis of opiate toxicity is facilitated by intravenous administration of the opiate antagonist naloxone, 0.01 mg/kg (2 mg is a common initial dose for an adolescent), which causes dilation of pupils constricted by the opiate. Diagnosis is confirmed by the finding of morphine in the serum.

Treatment

Treatment of acute heroin overdose consists of maintaining adequate oxygenation and continued administration of naloxone, a pure opioid antagonist. It may be given intravenously, intramuscularly, subcutaneously, or through the endotracheal tube. Naloxone has an ultrarapid onset of action (1 min) and a duration of action of 20-60 min. If there is no response then other etiologies for the respiratory depression must be explored. Naloxone may have to be continued for 24 hr if methadone, rather than shorter acting heroin, has been taken. Admission to the intensive care unit is indicated for patients who require continuous naloxone infusions (rebound coma, respiratory depression), and for those with life-threatening arrhythmias, shock, and seizures.

Baca CT, Grant KJ. Take-home naloxone to reduce heroin death. Addiction. 2005;100:1823-1831.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids among Medicaid enrollees—Washington, 2004–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1171-1174.

Doe-Simkins M, Walley AY, Epstein A, et al. Saved by the nose: bystander-administered intranasal naloxone hydrochloride for opioid overdose. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:788-791.

Fiellin DA. Treatment of adolescent opioid dependence. JAMA. 2008;300:2057-2058.

McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Cranford JA, et al. Motives for nonmedical use of prescription opioids among high school seniors in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:739-744.

Oviedo-Joekes E, Brissette S, Marsh DC, et al. Diacetylmorphine versus methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction. N Engl J Med. 361, 2009. 777–768

Woody GE, Poole SA, Subramaniam G, et al. Extended vs short-term buprenorphine-naloxone for treatment of opioid-addicted youth. JAMA. 2009;300:2003-2011.

2002 Acute reactions to drugs of abuse. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2002;44:21-24.

Bonomo Y, Proimos J. Substance misuse: alcohol, tobacco, inhalants, and other drugs. Br Med J. 2005;330:777-780.

Chandler RK, Fletcher BW, Volkow ND. Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system. JAMA. 2009;301:183-190.

Eaton D, Kann L, Shanklin S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(4):1-131.

Friedman RA. The changing face of teenage drug abuse—the trend toward prescription drugs. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1448-1450.

Haber PS, Demirkol A, Lange K, et al. Management of injecting drug users admitted to hospital. Lancet. 2009;374:1284-1292.

Hibell B, Guttormsson U, Ahlström S, et al. The 2007 ESPAD Report. Substance use among students in 35 European countries. The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs (CAN). Stockholm. 2009.

Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;16:12-20.

Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. Monitoring the future: national results on adolescent drug use: overview of key findings, 2008 (NIH Publication No. 09–7401). Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008.

Levy S, Sherritt L, Vaughn BL, et al. Results of random drug testing in an adolescent substance abuse program. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e843-e848.

Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, et al. Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. Lancet. 2007;369:1047-1053.

Toumbourou JW, Stockwell T, Neighbors C, et al. Interventions to reduce harm associated with adolescent substance use. Lancet. 2007;369:1391-1401.