Chapter 32 Language Development and Communication Disorders

Normal Language Development

For most children, learning to communicate in their native language is a naturally acquired skill whose potential is present at birth. No specific instruction is required, although children must be exposed to a language-rich environment. Normal development of speech and language is predicated on the infant’s ability to hear, see, comprehend, and remember. Equally important are sufficient motor skills to imitate oral motor movements, and the social ability to interact with others.

For the purposes of analysis, language is subdivided into several essential components. Communication consists of a wide range of behaviors and skills. At the level of basic verbal ability, phonology refers the correct use of speech sounds to form words, semantics refers to the correct use of words, and syntax refers to the appropriate use of grammar to make sentences. At a more abstract level, verbal skills include the ability to link thoughts together in a coherent fashion and to maintain a topic of conversation. Pragmatic abilities include verbal and nonverbal skills that facilitate the exchange of ideas, including the appropriate choice of language for the situation and circumstance and the appropriate use of body language (i.e., posture, eye contact, gestures). Social pragmatic and behavioral skills also play an important role in effective interactions with communication partners (i.e., engaging, responding, and maintaining reciprocal exchanges).

It is customary to divide language skills into receptive (hearing and understanding) and expressive (talking) abilities. Language development usually follows a fairly predictable pattern and parallels general intellectual development (Table 32-1).

Table 32-1 NORMAL LANGUAGE MILESTONES

| HEARING AND UNDERSTANDING | TALKING |

|---|---|

| BIRTH TO 3 MONTHS | |

| 4 TO 6 MONTHS | |

| 7 MONTHS TO 1 YEAR | |

| 1 TO 2 YEARS | |

| 2 TO 3 YEARS | |

| 3 TO 4 YEARS | |

| 4 TO 5 YEARS | |

From American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 2005. http://professional.asha.org.

Receptive Language Development

From birth, newborns demonstrate preferential response to human voices over inanimate sounds. The infant alerts and turns toward the direction of an adult who speaks in a soft, high-pitched voice. Over the first 3 mo, infants appear to recognize their parent’s voice and quiet if crying. Between 4 and 6 mo, infants visually search for the source of sounds, again showing a preference for the human voice over other environmental sounds. By 5 mo, infants can passively follow the adult’s line of visual regard, resulting in a “joint reference” to the same objects and events in the environment. The ability to share the same experience is critical to the development of further language, social, and cognitive skills. By 8 mo, the infant can actively show, give, and point to objects. Comprehension of words often becomes apparent by 9 mo, when the infant selectively responds to his or her name and appears to comprehend the word “no.” Social games, such as “peek-a-boo,” “so big,” and waving “bye-bye” can be elicited by simply mentioning the words. At 12 mo, many children can follow a simple, one-step request without a gesture (e.g., “Give it to me!”).

Between 1 and 2 yr, comprehension of language accelerates rapidly. Toddlers can point to body parts on command, identify pictures in books when named, and respond to simple questions (e.g., “Where’s your shoe?”). The 2 yr old is able to follow a 2-step command, employing unrelated tasks (e.g., “Take off your shoes, then go sit at the table”), and can point to objects described by their use (e.g., “Give me the one we drink from”). By 3 yr, children typically understand simple “wh-” question forms (e.g., who, what, where, why). By 4 yr, most children can follow adult conversation. They can listen to a short story and answer simple questions about it. Five yr olds typically have a receptive vocabulary of over 2000 words and can follow 3- and 4-step commands.

Expressive Language Development

Cooing noises are established by 4 to 6 wk of age. Over the first 3 mo of life, parents may distinguish their infant’s different vocal sounds for pleasure, pain, fussing, tiredness, etc. Many 3 mo old infants vocalize in a reciprocal fashion with an adult to maintain a social interaction (“vocal tennis”). By 4 mo, infants begin to make bilabial (“raspberry”) sounds, and by 5 mo monosyllables and laughing are noticeable. Between 6 and 8 mo, polysyllabic babbling (“lalala” or “mamama”) is heard and the infant might begin to communicate with gestures. Between 8 and 10 mo, babbling makes a phonologic shift toward the particular sound patterns of the child’s native language (i.e., they produce more native sounds than nonnative sounds). At 9 to 10 mo, babbling becomes truncated into specific words (e.g., “mama,” or “dada”) for their parents.

Over the next several mo, infants learn 1 or 2 words for common objects and begin to imitate words presented by an adult. These words might appear to come and go from the child’s repertoire until a stable group of 10 or more words is established. The rate of acquisition of new words is approximately 1 new word per wk at 12 mo, but it accelerates to approximately 1 new word per day by 2 yr. The first words to appear are used primarily to label objects (nouns) or to ask for objects and people (requests). By 18 to 20 mo, toddlers should use a minimum of 20 words and produce jargon (strings of word-like sounds) with language-like inflection patterns (rising and falling speech patterns). This jargon usually contains some embedded true words. Spontaneous 2-word phrases (pivotal speech), consisting of the flexible juxtaposition of words with clear intention (e.g., “Want juice!” or “Me down!”), is characteristic of 2 yr olds and reflects the emergence of grammatical ability (syntax).

Two-word, combinational phrases do not usually emerge until the child has acquired 50-100 words in their lexicon. Thereafter, the acquisition of new words accelerates rapidly. As knowledge of grammar increases, there is a proportional increase in verbs, adjectives, and other words that serve to define the relation between objects and people (predicates). By 3 yr, sentence length increases and the child uses pronouns and simple present tense verb forms. These 3-5 word sentences typically have a subject and verb but lack conjunctions, articles, and complex verb forms. The Sesame Street character Cookie Monster (“Me want cookie!”) typifies the “telegraphic” nature of the 3 yr old’s sentences. By 4-5 yr, children should be able to carry on conversations using adult-like grammatical forms and use sentences that provide details (e.g., “I like to read my books”).

Variations of Normal

Language milestones have been found to be largely universal across languages and cultures, with some variations depending on the complexity of the grammatical structure of individual languages. In Italian (where verbs often occupy a prominent position at the beginning or end of sentences), 14 mo olds produce a greater proportion of verbs compared with English speaking infants. Within a given language, development usually follows a fairly predictable pattern, paralleling general cognitive development. Although the sequences are predictable, the exact timing of achievement is not. There are marked variations among normal children in the rate of development of babbling, comprehension of words, production of single words, and use of combinational forms within the first 2-3 yr of life.

Two basic patterns of language learning have been identified: “analytic” and “holistic.” The analytic pattern is the most common and reflects the mastery of increasingly larger units of language form. As reflected in the previous discussion of milestones, the child’s analytic skills proceed from simple to more complex and lengthy forms. Children who follow a holistic or gestalt learning pattern might start by using relatively large chunks of speech in familiar contexts. They might memorize familiar phrases or dialogs from movies or stories and repeat them in an over-generalized fashion. Their sentences often have a formulaic pattern, reflecting inadequate mastery of the use of grammar to flexibly and spontaneously combine words appropriately in the child’s own unique utterance. Over time, these children gradually break down the meanings of phrases and sentences into their component parts, and they learn to analyze the linguistic units of these memorized forms. As this occurs, more original speech productions emerge and the child is able to assemble thoughts in a more flexible manner. Both analytic and holistic learning processes are necessary for normal language development to occur.

Language and Communication Disorders

Epidemiology

Disorders of speech and language affect up to 8% of preschool-aged children. Nearly 20% of 2 yr olds are thought to have delayed onset of speech. By age 5 yr, 19% of children are identified as having a speech and language disorder (6.4% speech impairment, 4.6% both speech and language impairment, and 8% language impairment). Boys are nearly twice as likely to have an identified speech or language impairment as girls.

Etiology

Normal language ability is a complex function that is widely distributed across the brain through interconnected neural networks that are synchronized for specific activities. Early researchers in language disorders, noting what appeared to be clinical parallels between acquired aphasia in adults and childhood language disorders, expected to find similar lesions in the brains of affected children. For the most part, unilateral, focal lesions acquired in early life do not seem to have the same effects in children as in adults. Furthermore, risk factors for neurologic injury are absent in the vast majority of children with language impairment.

Genetic factors appear to play a major role in influencing how children learn to talk. Language disorders appear to cluster in families. A careful family history may identify current or past speech or language problems in up to 30% of 1st-degree relatives of proband children. Although children who are exposed to parents with language difficulty might be expected to experience poor language stimulation and inappropriate language modeling, studies of twins have shown the concordance rate for low language test score and/or a history of speech therapy to be approximately 50% in dizygotic pairs, rising to over 90% in monozygotic pairs. A number of potential gene loci have been identified, but no consistent genetic markers have been established.

The most plausible genetic mechanism involves a disruption in the timing of early prenatal neurodevelopmental events affecting migration of nerve cells from the germinal matrix to the cerebral cortex. Chromosomal lesions and point mutations of the FOXP2 gene and polymorphisms of the CNTNAP2 gene are associated with an uncommon but distinct speech and language disorder characterized by difficulties in learning and producing oral movement sequences (developmental verbal dyspraxia, childhood apraxia of speech). Affected children have a spectrum of impairment in expressive and receptive language as well as problems understanding grammar.

Pathogenesis

Language disorders are associated with a fundamental deficit in the brain’s capacity to process complex information rapidly. Simultaneous evaluation of words (semantics), sentences (syntax), prosody (tone of voice), and social cues can overtax the child’s ability to comprehend and respond appropriately in a verbal setting. Limitations in the amount of information that can be stored in verbal working memory can further limit the rate at which language information is processed. Electrophysiologic studies have shown abnormal latency in the early phase of auditory processing in children with language disorders. Neuroimaging studies have identified an array of anatomic abnormalities in regions of the brain that are central to language processing. MRI scans in children with specific language impairment (SLI) can reveal white matter lesions, white matter volume loss, ventricular enlargement, focal gray matter heterotopia within the right and left parietotemporal white matter, abnormal morphology of the inferior frontal gyrus, atypical patterns of asymmetry of language cortex, or increased thickness of the corpus callosum. Postmortem studies of children with language disorders have found evidence of atypical symmetry in the plana temporale and cortical dysplasia in the region of the sylvian fissure. Additionally, some researchers have identified a high incidence of paroxysmal EEG anomalies during sleep in children with SLI. Although these findings might represent a mild variant of the Landau-Kleffner syndrome (acquired verbal auditory agnosia), they likely represent an epiphenomenon in which paroxysmal activity is related to architectural dysplasia. In support of a genetic mechanism affecting cerebral development, a high rate of atypical perisylvian asymmetries has also been documented in the parents of children with SLI.

Clinical Manifestations

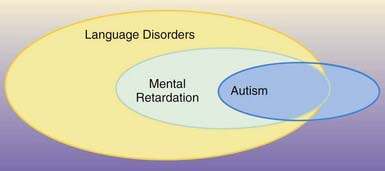

Primary disorders of speech and language development are often found in the absence of broader cognitive or motor dysfunction. Disorders of communication are the most common comorbid condition in persons with generalized cognitive disorders (intellectual disability or autism), structural anomalies of the organs of speech (velopharyngeal insufficiency from cleft palate), and neuromotor conditions affecting oral motor coordination (dysarthria from cerebral palsy or other neuromuscular disorders).

Classification

Each professional discipline has adopted a somewhat different classification system, based on cluster patterns of symptoms. One of the simplest classifications is the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) (Table 32-2). This system recognizes 4 types of communication disorders: expressive language disorder, mixed receptive-expressive language disorder, phonological disorder, and stuttering. In clinical practice, childhood speech and language disorders occur as a number of distinct entities.

Table 32-2 DSM-IV DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR COMMUNICATION DISORDERS

EXPRESSIVE LANGUAGE DISORDER

Coding note: If a speech-motor or sensory deficit or a neurologic condition is present, code the condition on Axis III

MIXED RECEPTIVE-EXPRESSIVE LANGUAGE DISORDER

Coding note: If a speech-motor or sensory deficit or a neurologic condition is present, code the condition on Axis III

PHONOLOGICAL DISORDER

Coding note: If a speech-motor a sensory deficit or a neurologic condition is present, code the condition on Axis III

STUTTERING

Coding note: If a speech-motor or sensory deficit or a neurologic condition is present, code the condition on Axis III

COMMUNICATION DISORDER NOT OTHERWISE SPECIFIED

This category is for disorders in communication that do not meet the criteria for any specific communication disorder; for example, a voice disorder (i.e., an abnormality of vocal pitch, loudness, quality, tone, or resonance)

Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, ed 4, Washington, DC, 1994, American Psychiatric Association, pp 58, 60–61, 63, 65.

Specific Language Impairment

Also referred to as developmental dysphasia, or developmental language disorder, SLI is characterized by a significant discrepancy between the child’s overall cognitive level (typically nonverbal measures of intelligence) and functional language level. In addition, these children follow an atypical pattern of language acquisition and use. Closer examination of the child’s skills might reveal deficits in understanding and use of word meaning (semantics) and grammar (syntax). Often, children with SLI are delayed in starting to talk. Most significantly, they usually have difficulty understanding spoken language. The problem may stem from insufficient understanding of single words or from the inability to deconstruct and analyze the meaning of sentences. Many affected children show a holistic pattern of language development, repeating memorized phrases or dialog from movies or stories (echolalia). In contrast to their difficulty with spoken language, children with SLI appear to learn visually and demonstrate their ability on nonverbal tests of intelligence.

Although they have difficulty interacting with peers who are more verbally adept, many children with SLI play appropriately with younger or older children. Despite their communication impairment, they engage in pretend play, show imagination, share emotions (affective reciprocity), and demonstrate joint referencing behaviors appropriate to their age. Of note is the high incidence of fine-motor coordination difficulty found in these children. A combination of increased joint mobility and mild muscular hypotonia often results in motor clumsiness.

Over time, children with SLI respond to therapeutic/educational interventions and show a trend toward improvement of communication skills. Adults with a history of childhood language disorder continue to show evidence of impaired language ability, even when surface features of the communication difficulty have improved considerably. This suggests that many persons find successful ways of adapting to their impairment.

Many children with SLI show difficulties with social interaction, particularly with same-aged peers. Social interaction is mediated by oral communication, and a child deficient in communication is at a distinct disadvantage in the social arena. Children with SLI tend to be more dependent on older children or adults, who can adapt their communication to match the child’s level of function. They might gravitate toward younger children who communicate at a level they can comprehend. Generally, social interaction skills are more closely correlated with language level than with nonverbal cognitive level. Using this as a guide, one usually sees a developmental progression of increasingly more sophisticated social interaction as the child’s language abilities improve. In this context, social ineptitude is not necessarily a sign of asocial distancing (e.g., autism) but rather a delay in the ability to negotiate social interactions.

Pragmatic Language Disorder

The ability to communicate effectively with others depends on mastery of a range of skills that go beyond basic understanding of words and rules of grammar. These higher-order abilities include knowledge of the conversational partner, knowledge of the social context in which the conversation is taking place, and general knowledge of the world. Social and linguistic aspects of communication are often difficult to tease apart, and persons who have trouble interpreting these relatively abstract aspects of communication typically experience difficulty forming and maintaining relationships. Symptoms of pragmatic difficulty include extreme literalness and inappropriate verbal and social interactions. Proper use and understanding of humor, slang, and sarcasm depend on correct interpretation of the meaning and the context of language and the ability to draw proper inferences. Failure to provide a sufficient referential base to one’s conversational partner—to take the perspective of another person—results in the appearance of talking or behaving randomly or incoherently. Pragmatic language impairment often occurs in the context of SLI, but it has been recognized as a symptom of a wide range of disorders, including right-hemisphere damage to the brain, autism, Asperger’s syndrome, Williams syndrome, and nonverbal learning disabilities.

Mental Retardation

Most children with a mild degree of mental retardation learn to talk at a slower than normal rate; they follow a normal sequence of language acquisition and eventually master basic communication skills. Difficulties may be encountered with higher-level language concepts and use. Persons with moderate to severe degrees of cognitive retardation can have great difficulty in acquiring basic communication skills. About half of persons with IQ <50 are able to communicate using single words or simple phrases; the rest are typically nonverbal.

Autism and Pervasive Developmental Disorders

A disordered pattern of language development is one of the core features of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders (Chapter 28). In fact, the language profile of children with autism is indistinguishable from that in children with SLIs. The key points of distinction between these conditions are the lack of reciprocal social relationships that characterizes children with autism, limitation in the ability to develop functional, symbolic, or pretend play, and an obsessive need for sameness and resistance to change. Approximately 75-80% of children with autism are also mentally retarded, and this can limit their ability to develop functional communication skills. Language abilities can range from absent to grammatically intact, but with limited pragmatic features and/or odd prosody patterns. Some autistic persons have highly specialized, but isolated, “savant” skills, such as calendar calculations and hyperlexia (the precocious ability to recognize written words beyond expectation based on general intellectual ability). Regression in language and social skills (autistic regression) occurs in approximately one third of children with autism, usually before 2 yr of age. No explanation for this phenomenon has been identified. Once the regression has “stabilized,” recovery of function does not usually occur (Fig. 32-1).

Asperger’s Syndrome (Chapter 28.2)

Although sharing many characteristics of autism (deficits in social relatedness and restricted range of interests), individuals with Asperger syndrome typically show normal early language development (syntax and semantics). As they mature, higher-order social and language pragmatic impairments become prominent features of this disorder. Affected children have an unusually circumscribed range of interests, which are all-absorbing and interfere with learning of other skills and with social adaptation. These children may engage in long-winded, verbose monologues about their topics of special interest, with little regard to the reaction of others. Their inflection pattern (prosody) may be inappropriate to the content of their conversation, and they might not adjust their rate of speech or vocal volume to the setting.

Selective Mutism

Selective mutism is defined as a failure to speak in specific social situations despite speaking in other situations, and it is typically a symptom of an underlying anxiety disorder. Children with selective mutism can speak normally in certain settings, such as within their home or when they are alone with their parents. They fail to speak in other social settings, such as at school or at other places outside their home. Other symptoms associated with selective mutism can include excessive shyness, withdrawal, dependency on parents, and oppositional behavior. Most cases of selective mutism are not the result of a single traumatic event, but rather are the manifestation of a chronic pattern of anxiety. Mutism is not passive-aggressive behavior. Mute children report that they want to speak in social settings but are afraid to do so. It is important to emphasize that the underlying anxiety disorder is the likely origin of selective mutism. Often, one or both parents of a child with selective mutism has a history of anxiety symptoms, including childhood shyness, social anxiety, or panic attacks. This suggests that the child’s anxiety represents a familial trait. For some unknown reason, the child converts the anxiety into the mute symptom. The mutism is highly functional for the child in that it reduces anxiety and protects the child from the perceived challenge of social interaction. Treatment of selective mutism should focus on reducing the general anxiety, rather than focusing only on the mute behaviors (Chapter 23). Selective mutism reflects a difficulty of social interaction and not a disorder of language processing.

Isolated Expressive Language Disorder

More commonly seen in boys than girls, isolated expressive language disorder (late talker syndrome) is a diagnosis best made in retrospect. These children have age-appropriate receptive language and social ability. Once they start talking, their speech is clear. There is no increased risk for language or learning disability as they progress through school. A family history of other males with a similar developmental pattern is often reported. This pattern of language development likely reflects a variation of normal.

Motor Speech Disorders

Dysarthria

Motor speech disorders can originate from neuromotor disorders such as cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, myopathy, facial palsy. The resulting dysarthria affects both speech and nonspeech functions (smiling and chewing). Lack of strength and muscular control manifests as slurring of words and distorting of vowels. Speech patterns are often slow and labored. Poor velopharyngeal function can result in mixed nasal resonance (hyper- or hyponasal speech). In many cases, feeding difficulty, drooling, open mouth posture, and a protruding tongue accompany the dysarthric speech.

Verbal Apraxia

Difficulty in planning and coordinating movements for speech production can result in inconsistent distortion of speech sounds. The same word may be pronounced differently each time. Intelligibility tends to decline as the length and complexity of the child’s speech increases. Consonants may be deleted and sounds transposed. As they try to talk spontaneously, or imitate other’s speech, children with verbal apraxia may display oral groping or struggling behaviors. Often, children with verbal apraxia have a history of early feeding difficulty, limited sound production as infants, and delayed onset of spoken words. They may point, grunt, or develop an elaborate gestural communication system in an attempt to overcome their verbal difficulty. Apraxia may be limited to oral-motor function, or it may be a more generalized problem affecting fine and/or gross motor coordination.

Phonologic Disorder

Children with phonologic speech disorder are often unintelligible, even to their parents. Articulation errors are not the result of neuromotor impairment but seem to reflect an inability to correctly process the words they hear. As a result, they lack understanding of how to fit sounds together properly to create words. In contrast to children with apraxia, those with phonologic disorder are fluent—although unintelligible—and produce a consistent, highly predictable pattern of articulation errors. Children with phonologic speech disorder are at high risk for later reading and learning disability.

Hearing Impairment

Hearing loss can be a major cause of delayed or disordered language development (Chapter 629). Approximately 16-30 per 1,000 children have mild to severe hearing loss, significant enough to affect educational progress. In addition to these “hard of hearing” children, approximately another 1 per 1,000 are deaf (profound bilateral hearing loss). Hearing loss can be present at birth or acquired postnatally. Newborn screening programs can identify many forms of congenital hearing loss, but children can develop progressive hearing loss or acquire deafness after birth.

The most common types of hearing loss are due to conductive (middle ear) or sensorineural deficit. Although it is not possible to accurately predict the impact of hearing loss on a child’s language development, the type and degree of hearing loss, the age of onset, and the duration of the auditory impairment clearly play important roles. Children with significant hearing impairment often have problems developing facility with language and often have related academic difficulties. Presumably, the language impairment is caused by lack of exposure to fluent language models starting in infancy.

Approximately 30% of hearing-impaired children have at least one other disability that affects development of speech and language (e.g., mental retardation, cerebral palsy, craniofacial anomalies). Any child who shows developmental warning signs of a speech or language problem should have a hearing assessment by an audiologist and an examination by a geneticist as part of a comprehensive evaluation.

Hydrocephalus

Children with hydrocephalus are described as having “cocktail-party syndrome.” Although they may use sophisticated words, their comprehension of abstract concepts is limited, and their pragmatic conversational skills are weak. As a result, they speak superficially about topics and appear to be carrying on a monologue (Chapter 585.11).

Rare Causes of Language Impairment

Hyperlexia

Hyperlexia is the precocious development of reading single words that spontaneously occurs in some young children (2-5 yr) without specific instruction. It is typically associated with children who have a pervasive developmental disorder (PDD) or SLI. It stands in contrast to precocious reading development in young children who do not have any other developmental disorders. Hyperlexia is a variation seen in young children with disordered language who do not have the social deficits or restricted or repetitive behaviors associated with autism. A typical manifestation is for a child with SLI to orally read single words, or match pictures with single words. Although hyperlexic children show early and well-developed word-decoding skills, they usually have no precocious ability for comprehension of text. Rather, text comprehension is closely intertwined with oral comprehension, and children who have difficulty decoding the syntax of language are also at risk for having reading comprehension problems.

Landau-Kleffner Syndrome (Verbal Auditory Agnosia)

Children with Landau-Kleffner syndrome have a history of normal language development until they experience a regression in their ability to comprehend spoken language (verbal auditory agnosia). The regression may be sudden or gradual, and it usually occurs between 3 and 7 yr of age. Expressive language skills typically deteriorate, and some children may become mute. Despite their language regression, these children typically retain appropriate play patterns and the ability to interact in a socially appropriate manner. An EEG might show a distinct pattern of status epilepticus in sleep (continuous spike-wave in slow-wave sleep), and up to 80% of children with this condition eventually exhibit clinical seizures. A number of treatment approaches have been reported, including antiepileptic medication, steroids, and intravenous gamma globulin, with varying results. The prognosis for return of normal language ability is uncertain, even with resolution of the EEG abnormality, which can represent an epiphenomenon of an underlying brain abnormality.

Metabolic and Neurodegenerative Disorders (See Also Part XI)

Regression of language development may accompany loss of neuromotor function at the outset of a number of metabolic diseases including lysosomal storage disorders (metachromatic leukodystrophy), peroxisomal disorders (adrenal leukodystrophy), ceroid lipofuscinosis (Batten’s disease), and mucopolysaccharidosis (Hunter’s disease, Hurler’s disease). Recently, creatine transporter deficiency was identified as an X-linked disorder that manifests with language delay in boys and mild learning disability in female carriers.

Screening

At each well child visit, developmental surveillance should include specific questions about normal language developmental milestones and observations of the child’s behavior. Clinical judgment, defined as eliciting and responding to parents’ concerns, can detect the majority of children with speech and language problems. Many clinicians employ standardized developmental screening questionnaires and observation checklists designed for use in a pediatrics office (Chapter 14).

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reviewed screening instruments for speech and language delays in young children that can be used in primary care settings. The Task Force focused on brief measures that require <10 minutes to complete. There was insufficient evidence that screening instruments are more effective than using physician’s clinical observations and parents’ concerns to identify children who require further evaluation. The Task Force noted that there is no single gold standard for screening, owing to inconsistent measures and terminology, and did not recommend the use of screening instruments. Furthermore, the Task Force determined that the use of formal measures was not time or cost efficient and deferred to pediatrician’s and parents’ concerns as indicators of potential problems. Table 32-3 offers guidelines for raising concerns and referring a child for specialized speech and language evaluation. Because of the high prevalence of speech and language disorders in the general population, referral to a speech-language pathologist for further evaluation should be made whenever there is a suspicion of delay.

Table 32-3 SPEECH AND LANGUAGE SCREENING

| REFER FOR SPEECH-LANGUAGE EVALUATION IF: | ||

|---|---|---|

| AT AGE | RECEPTIVE | EXPRESSIVE |

| 15 mo | Does not look/point at 5-10 objects | Is not using 3 words |

| 18 mo | Does not follow simple directions (“get your shoes”) | Is not using Mama, Dad, or other names |

| 24 mo | Does not point to pictures or body parts when they are named | Is not using 25 words |

| 30 mo | Does not verbally respond or nod/shake head to questions | Is not using unique 2-word phrases, including noun-verb combinations |

| 36 mo | Does not understand prepositions or action words; does not follow 2-step directions | Has a vocabulary <200 words; does not ask for things; echolalia to questions; language regression after attaining 2-word phrases |

Non-Causes of Language Delay

Twinning, birth order, “laziness,” exposure to multiple languages (bilingualism), tongue-tie, or otitis media are not adequate explanations for significant language delay. Normal twins learn to talk at the same age as normal single-born children, and birth order effects on language development have not been consistently found. The drive to communicate and the rewards for successful verbal interaction are so strong that children who let others talk for them usually can’t talk for themselves and are not “lazy.” Toddlers exposed to more than one language can show a mild delay in starting to talk, and they can initially mix elements (vocabulary and syntax) of the different languages they are learning (code switching). However, they learn to segregate each language by 24-30 mo and are equal to their monolingual peers by 3 yr of age. An extremely tight lingual frenulum (tongue-tie) can affect feeding and speech articulation but does not prevent the acquisition of language abilities. Finally, prospective studies have shown that frequent ear infections and/or serous otitis media in early childhood do not result in language disorder.

Diagnostic Evaluation

It is important to distinguish developmental delay (abnormal timing) from developmental disorder (abnormal patterns or sequences). A child’s language and communication skills must also be interpreted within the context of his or her overall cognitive and physical abilities. Finally, it is important to evaluate the child’s use of language to communicate with others in the broadest sense (communicative intent). Thus, a multidisciplinary evaluation is often warranted. At a minimum this should include psychologic evaluation, neurologic assessment, and speech and language examination.

Psychologic Evaluation

There are two main goals for the psychologic evaluation of a young child with a communication disorder. Nonverbal cognitive ability must be assessed to determine if the child is mentally retarded, and the child’s social behaviors must be assessed to determine whether autism or a form of PDD is present. Additional diagnostic considerations may include emotional disorders such as anxiety, depression, mood disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, academic learning disorders, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Cognitive Assessment

Mental retardation (intellectual disability) is defined as retardation in development of cognitive abilities and adaptive behaviors. In this context, children with mental retardation show delayed development of communication skills; however, delayed communication does not necessarily signal mental retardation. Therefore, a broad-based cognitive assessment is an important component to the evaluation of children with language delays, including evaluation of both verbal and nonverbal skills. If a child has mental retardation, both verbal and nonverbal scores will be low compared to norms (≤2nd percentile). In contrast, a typical cognitive profile for a child with SLI includes a significant difference between nonverbal and verbal abilities, with nonverbal IQ > verbal IQ and the nonverbal score within an average range.

Evaluation of Social Behaviors

Social interest is the key difference between children with a primary language disorder (SLI) and those with a communication disorder secondary to autism or PDD. Children with SLI have an interest in social interaction, but they may have difficulty enacting their interest because of their limitations to communication. In contrast, autistic children show little social interest. Four key nonverbal behaviors that are often shown by children with SLI—but not autistic children (especially toddlers and preschoolers)—are joint attention, affective reciprocity, pretend play, and direct imitation.

Relationship of Language and Social Behaviors to Mental Age

Cognitive assessment provides a mental age for the child, and the child’s behavior must be evaluated in that context. Most 4 yr old children typically engage peers in interactive play, but most 2 yr olds are playful but primarily focused on interactions with adult caretakers. A 4 yr old with mild to moderate mental retardation and a mental age of 2 yr might not play with peers yet because of cognitive limitation, not a lack of desire for social interaction.

Speech and Language Evaluation

A certified speech-language pathologist should perform a speech and language evaluation. A typical evaluation includes assessment of language, speech, and the physical mechanisms associated with speech production. Both expressive and receptive language is assessed by a combination of standardized measures and informal interactions and observations. All components of language are assessed, including syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and fluency. Speech assessment similarly uses a combination of standardized measures and informal observations. Assessment of physical structures includes oral structures and function, respiratory function, and vocal quality. In many settings, a speech-language pathologist works in conjunction with an audiologist, who can do appropriate hearing evaluation of the child. If an audiologist is not available in that setting, then a separate referral should be made. No child is too young for a speech and language or hearing evaluation. A referral for evaluation is appropriate whenever there is suspicion of language impairment.

Medical Evaluation

As in any developmental disorder, careful history and physical examination should focus on the identification of potential contributors to the child’s language and communication difficulties. A family history of delay in talking, need for speech and language therapy, or academic difficulty can suggest a genetic predisposition to language disorders. Pregnancy history might reveal risk factors for prenatal developmental anomalies, such as polyhydramnios or decreased fetal movement patterns. Small size for gestational age at birth, symptoms of neonatal encephalopathy, or early and persistent oral-motor feeding difficulty may presage speech and language difficulty. Developmental history should focus on the age at which various language skills were mastered and the sequences and patterns of milestone acquisition. Regression or loss of acquired skills should raise immediate concern.

Physical examination should include measurement of height (length), weight, and head circumference. The skin should be examined for lesions consistent with phakomatosis (e.g., tuberous sclerosis, neurofibromatosis, Sturge-Weber syndrome) and other disruptions of pigment (hypomelanosis of Ito). Anomalies of the head and neck, such as white forelock and hypertelorism (Waardenberg syndrome), ear malformations (Goldenhar syndrome), facial and cardiac anomalies (Williams syndrome, velocardiofacial syndrome), retrognathism of the chin (Pierre-Robin anomaly), or cleft lip and/or palate, are associated with hearing and speech abnormalities. Neurologic examination might reveal muscular hypertonia or hypotonia, both of which can affect neuromuscular control of speech. Generalized muscular hypotonia, with increased range of motion of the joints, is commonly seen in children with SLI. The reason for this association is not clear but it might account for the fine and gross motor clumsiness often seen in these children. However, mild hypotonia is not a sufficient explanation for the impairments of expressive and receptive language.

No routine diagnostic studies are indicated for SLI or isolated language disorders. When language delay is a part of a generalized cognitive or physical disorder, referral for further genetic evaluation, chromosome testing (including high resolution banding karyotype, fragile X testing, and microarray comparative genomic hybridization), neuroimaging studies, and EEG may be considered, if clinically indicated.

Treatment

The federal IDEA laws (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act) require that schools provide special education services to children who have learning difficulties. This includes children with speech and language disorders. Services are provided to children from birth through 21 yr of age. Each state has various methods for providing services, and for young children these can include Birth-to-Three, Early Childhood, and Early Learning programs. These programs provide speech-language therapy as part of public education, in conjunction with other special education resources. Children can also receive therapy from nonprofit service agencies, hospital and rehabilitation centers, and speech pathologists in private practice.

Speech-language therapy includes a variety of goals. Sometimes both speech and language activities are incorporated in therapy. The speech goals focus on development of more intelligible speech. Language goals can focus on expanding vocabulary (lexicon) and understanding of the meaning of words (semantics), improving syntax by using proper forms or learning to expand single words into sentences, and social use of language (pragmatics). Therapy can include individual sessions, group sessions, and mainstream classroom integration. Individual sessions may use drill activities for older children or play activities for younger children to target specific goals. Group sessions can include several children with similar language goals to help them practice peer communication activities and to help them bridge the gap into more naturalistic communication situations. Classroom integration might include the therapist team-teaching or consulting with the teacher to facilitate the child’s use of language in common academic situations.

For children with severe language impairment, alternative methods of communication are often included in therapy. These may include use of manual sign language, use of pictures (e.g., Picture Exchange Communication System—PECS), and computerized devices for speech output. Often the ultimate goal is to achieve better spoken language. Early use of signs or pictures can help the child to establish better functional communication and help the child to understand the symbolic nature of words to facilitate the language process. There is no evidence that use of signs or pictures interferes with development of oral language if the child has the capacity to speak. Many clinicians believe that these alternative methods accelerate the learning of language. They also reduce frustration of parents and children who cannot communicate for basic needs.

Parents can consult with their child’s speech-language therapist about home activities to enhance language development and extend therapy activities through appropriate language-stimulating activities and recreational reading. Parents’ language activities should focus on emerging communication skills that are within the child’s repertoire, rather than teaching the child new skills. The speech pathologist can guide parents on effective modeling and eliciting communication from their child.

Recreational reading focuses on expanding the child’s comprehension of language. Sometimes the child’s avoidance of reading is a sign that the parent is presenting material that is too complex for the child. The speech-language therapist can guide the parent in selecting an appropriate level of reading material.

Prognosis

Although the majority of children improve their communication ability with time, 50-80% of preschoolers with language delay and normal nonverbal intelligence continue to show language difficulties up to 20 yr beyond the initial diagnosis. Early language difficulty is strongly related to later reading disorder. Approximately 50% of children with early language difficulty develop reading disorder, and 55% of children with reading disorder have a history of impaired early oral language development. Studies have shown that children who eventually manifest a specific reading disorder produce fewer words per utterance, express less-complicated sentences, and show more pronunciation difficulties at 2-3 yr of age compared with peers who do not have reading disorders. By 5 yr of age, verbal sentence complexity had little predictive power, but expressive vocabulary and phonologic awareness of words (the ability to manipulate the component sounds of words) were highly correlated with later reading achievement.

Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders

Early language disorder, particularly difficulty with auditory comprehension, appears to be a specific risk factor for later emotional dysfunction. Boys and girls with language disorder have a higher than expected rate of anxiety disorder (principally social phobia). Boys with language disorder are more likely to develop symptoms of ADHD, conduct disorder, and antisocial personality disorder compared with normally developing peers. Language disorders are common in children referred for psychiatric services, but they are often underdiagnosed, and their impact on children’s behavior and emotional development is often overlooked.

Preschoolers with language difficulty commonly express their frustration through anxious, socially withdrawn, or aggressive behavior. As their ability to communicate improves, parallel improvements are usually noted in their behavior, suggesting a cause-and-effect relationship between language and behavior. However, the persistence of emotional and behavioral problems over the lifespan of persons with early language disability suggests a strong biologic or genetic connection between language development and subsequent emotional disorders.

Cohen NJ, Barwick MA, Horodezky NB, et al. Language, achievement, and cognitive processing in psychiatrically disturbed children with previously identified and unsuspected language impairments. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1998;39:865-877.

Cohen NJ, Davine M, Horodezky N, et al. Unsuspected language impairment in psychiatrically disturbed children: prevalence and language and behavioral characteristics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:595-603.

De Fosse L, Hodge SM, Makris N, et al. Language-association cortex asymmetry in autism and specific language impairment. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:757-766.

Feldman HM. Evaluation and management of language and speech disorders in preschool children. Pediatr Rev. 2005;26:131-141.

Giddan JJ, Milling L, Campbell NB. Unrecognized language and speech deficits in preadolescent psychiatric inpatients. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:85-92.

Herbert MR, Kenet T. Brain abnormalities in language disorders and in autism. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:563-583.

Hill EL. A dyspraxic deficit in specific language impairment and developmental coordination disorder? Evidence from hand and arm movements. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40:388-395.

Kennedy CR, McCann DC, Campbell MJ, et al. Language ability after early detection of permanent childhood hearing impairment. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2131-2140.

Nelson HD, Nygren P, Walker M, et al. Screening for speech and language delay in preschool children: systematic evidence review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e298-e319.

Rapin I, Dunn M. Update on the language disorders of individuals on the autistic spectrum. Brain Dev. 2003;25:166-172.

Reilly S, Onslow M, Packman A, et al. Predicting stuttering onset by the age of 3 years: a prospective, community cohort study. Pediatrics. 2009;123:270-277.

Roberts JE, Rosenfeld RM, Zeisel SA. Otitis media and speech and language: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):e238-e248.

Schum R. Language screening in the pediatric office setting. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:425-436.

Tager-Flusberg H, Caronna E. Language disorders: autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:469-481.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for speech and language delay in preschool children: recommendation statement. Pediatrics. 2006;117:497-501.

Ward D. The aetiology and treatment of developmental stammering in childhood. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:68-71.

32.1 Dysfluency (Stuttering, Stammering)

Fluent speech requires timely synchronization of phonatory and articulatory muscle groups. There is also an important interaction between speech and language skills. Stuttering involves involuntary frequent repetitions, lengthenings (prolongations) or arrests (blocks, pauses) of syllables, or sounds that are exacerbated by emotionally or syntactically demanding speech. The World Health Organization’s definition of stuttering is a disorder in the rhythm of speech in which the person knows precisely what he or she wishes to say but at the same time may have difficulty saying it because of an involuntary repetition, prolongation, or cessation of sound. Stuttering often leads to frustration and avoidance of speaking situations. Stuttering can lead to being bullied or teased and to speech-related anxiety and social phobia.

Epidemiology and Etiology

Stuttering usually begins at 2-4 yr of age and is seen more often in boys (4 : 1). Approximately 3-5% of preschool children stutter to some degree; only 0.7-1% of young adults stutter. Stuttering is common in families. Stuttering may occur suddenly and often begins when word combinations are involved. Higher vocabulary at age 2 yr and higher material education may also be associated with stuttering. Girls and those with a family history of recovery are most likely to have spontaneous recovery by adolescence. This recovery is not related to the severity of the stuttering. About 75% stop stuttering by adolescence, ∼ 90% for girls.

Stuttering may be due to impaired timing between areas of the brain involved in language preparation and execution. Adults who stutter and those with fluent speech activate similar areas of the brain. In addition, adults who stutter overactivate parts of the motor cortex and cerebellar vermis, show right-sided laterality, and have no auditory activation on hearing their own speech.

Diagnosis

Stuttering must be differentiated from the normal developmental dysfluency of preschool children (Tables 32-4 and 32-5). Developmental dysfluency is characterized by brief periods of stuttering that resolve by school age, and it usually involves whole words, with <10 dysfluencies per 100 words. The DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for stuttering are noted in Table 32-2. Stuttering that persists and is associated with tics may be a manifestation of Tourette’s syndrome (Chapters 23 and 590).

Table 32-4 DIFFERENCES BETWEEN STUTTERING AND DEVELOPMENTAL DYSFLUENCY

| BEHAVIOR | STUTTERING | DEVELOPMENTAL DYSFLUENCY |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency of syllable repetition per word | ≥2 | ≤1 |

| Tempo | Faster than normal | Normal |

| Airflow | Often interrupted | Rarely interrupted |

| Vocal tension | Often apparent | Absent |

| Frequency of prolongations per 100 words | ≥2 | ≤1 |

| Duration of prolongation | ≥2 sec | ≤1 sec |

| Tension | Often present | Absent |

| Silent pauses within a word | May be present | Absent |

| Silent pauses before a speech attempt | Unusually long | Not marked |

| Silent pauses after the dysfluency | May be present | Absent |

| Articulating postures | May be inappropriate | Appropriate |

| Reaction to stress | More broken words | No change in dysfluency |

| Frustration | May be present | Absent |

| Eye contact | May waver | Normal |

Adapted with permission from Van Riper C: The nature of stuttering, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 1971, p 28. From Lawrence M, Barclay DM III: Stuttering: a brief review, Am Fam Physician 57:2175-2178, 1998.

Table 32-5 EXAMPLES OF NORMAL DYSFLUENCY IN PRESCHOOLERS

| TYPE OF DYSFLUENCY | EXAMPLES |

|---|---|

| Voiced repetitions | Occasionally 2 word parts (mi … milk) Single-syllable words (I … I see you) Multisyllabic words (Barney … Barney is coming!) Phrases (I want … I want Elmo.) |

| Interjections | We went to the … uh … cottage. |

| Revisions: incomplete phrases | I lost my. … Where is Daddy going? |

| Prologations | I am Toooommy Baker. |

| Tense pauses | Lips together, no sound produced |

From Costa D, Kroll R: Stuttering: an update for physicians, CMAJ 162:1849–1855, 2000.

Treatment

Preschool children with developmental dysfluency (see Table 32-5) can be observed with parental education and reassurance. Parents should not reprimand the child or create undue anxiety. Preschool or older children with stuttering should be referred to a speech pathologist. Therapy is most effective if started during the preschool period. In addition to the risks noted in Table 32-3, indications for referral include 3 or more dysfluencies per 100 syllables (b-b-but; th-th-the; you, you, you), avoidances or escapes (pauses, head nod, blinking), discomfort or anxiety while speaking, and suspicion of an associated neurologic or psychotic disorder.

Most preschool children respond to interventions taught by speech pathologists and to behavioral feedback by parents. Parents should not yell at the child, but should calmly praise periods of fluency (“That was smooth”) or nonjudgmentally note episodes of stuttering (“That was a bit bumpy”). The child can be involved with self-correction and respond to requests (“Can you say that again?”) made by a calm parent.

Older children, adolescents, and adults have also been treated with risperidone or olanzapine with varying but usually positive results if behavioral speech therapy is unsuccessful.

Grizzle KL, Simms MD. Language and learning: a discussion of typical and disordered development. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2009;39:168-189.

Johnson CJ, Beitchman JH, Young A, et al. Fourteen-year follow-up of children with and without speech/language impairments: speech/language stability and outcomes. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1999;42:744-760.

Peterson RL, McGrath LM, Smith SD, et al. Neuropsychology and genetics of speech, language, and literacy disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:543-561.

Rinaldi W. Pragmatic comprehension in secondary school-aged students with specific developmental language disorder. Int J Lang Comm Dis. 2000;35:1-29.

Sharp HM, Hillenbrand K. Speech and language development and disorders in children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55:1159-1173. viii

Shevell MI, Majnemer A, Webster RI, et al. Outcomes at school age of preschool children with developmental language impairment. Pediatr Neurol. 2005;32:264-269.

Simms MD. Language disorders in children: classification and clinical syndromes. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2007;54:437-467.

Simms MD, Schum RL. Preschool children who have atypical patterns of development. Pediatr Rev. 2000;21:147-158.

Spinath FM, Price TS, Dale PS, et al. The genetic and environmental origins of language disability and ability. Child Dev. 2004;75:445-454.

Stromswold K. The genetics of speech and language impairments. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2381-2383.

Trauner D, Wulfeck B, Tallal P, et al. Neurological and MRI profiles of children with developmental language impairment. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2000;42:470-475.

Verned SC, Newbury DF, Abrahams BS, et al. A functional genetic link between distinct developmental language disorders. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2337-2345.

Webster RI, Majnemer A, Platt RW, et al. Motor function at school age in children with a preschool diagnosis of developmental language impairment. J Pediatr. 2005;146:80-85.

Webster RI, Shevell MI. Neurobiology of specific language impairment. J Child Neurol. 2004;19:471-481.