Chapter 42 Feeding Healthy Infants, Children, and Adolescents

Early feeding and nutrition play important roles in the origin of adult diseases such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome; therefore, appropriate feeding practices should be established in the neonatal period and carried out as a continuum from childhood and adolescence to adulthood. Optimal neonatal feeding practices require a multidisciplinary approach among health care providers, including physicians, nursing staff, nutritionists, and lactation consultants. Whether by breast or by bottle, successful infant feeding requires education and a supportive environment conducive to successful transition from fetal to neonatal life.

Feeding During the First Year of Life

Breast-feeding

Feedings should be initiated soon after birth unless medical conditions preclude them. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and World Health Organization (WHO) strongly advocate breast-feeding as the preferred feeding for all infants. The success of breast-feeding initiation and continuation depends on multiple factors, such as education about breast-feeding, hospital breast-feeding practices and policies, routine and timely follow-up care, and family and societal support (Table 42-1). The AAP recommends exclusive breast-feeding for a minimum of 4 mo and preferably for 6 mo. The advantages of breast-feeding are well documented (Tables 42-2 and 42-3), and contraindications are rare (Table 42-4).

Table 42-1 STEPS TO ENCOURAGE BREAST-FEEDING IN THE HOSPITAL: UNICEF/WHO BABY-FRIENDLY

HOSPITAL INITIATIVES

MOTHERS TO LEARN

ADDITIONAL INSTRUCTIONS

UNICEF, United Nations Children’s Fund; WHO, World Health Organization.

Table 42-2 SELECTED BENEFICIAL PROPERTIES OF HUMAN MILK COMPARED TO INFANT FORMULA

| Secretory lgA | Specific antigen-targeted anti-infective action |

| Lactoferrin | Immunomodulation, iron chelation, antimicrobial action, antiadhesive, trophic for intestinal growth |

| κ-casein | Antiadhesive, bacterial flora |

| Oligosaccharides | Prevention of bacterial attachment |

| Cytokines | Anti-inflammatory, epithelial barrier function |

| Growth factors | |

| Epidermal growth factor | Luminal surveillance, repair of intestine |

| Transforming growth factor (TGF) | |

| Nerve growth factor | Promotes neural growth |

| Enzymes | |

| Platelet-activating factor-acetylhydrolase | Blocks action of platelet activating factor |

| Glutathione peroxidase | Prevents lipid oxidation |

| Nucleotides | Enhance antibody responses, bacterial flora |

Table 42-3 CONDITIONS FOR WHICH HUMAN MILK HAS BEEN SUGGESTED TO HAVE A PROTECTIVE EFFECT

Adapted from the Schanler RJ, Dooley S: Breastfeeding handbook for physicians, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2006, American Academy of Pediatrics.

Table 42-4 ABSOLUTE AND RELATIVE CONTRAINDICATIONS TO BREAST-FEEDING DUE TO MATERNAL HEALTH CONDITIONS

| MATERNAL HEALTH CONDITIONS | DEGREE OF RISK |

|---|---|

| HIV and HTLV infection | |

| Tuberculosis infection | Breast-feeding is contraindicated until completion of approximately 2 wk of appropriate maternal therapy |

| Varicella-zoster infection | |

| Herpes simplex infection | Breast-feeding is contraindicated with active herpetic lesions of the breast |

| CMV infection | |

| Hepatitis B infection | |

| Hepatitis C infection | Breast-feeding is not contraindicated |

| Alcohol intake | Limit maternal alcohol intake to <0.5 g/kg/day (for a woman of average weight, this is the equivalent of 2 cans of beer, 2 glasses of wine, or 2 oz of liquor) |

| Cigarette smoking | Discourage cigarette smoking, but smoking is not a contraindication to breast-feeding |

| Chemotherapy, radiopharmaceuticals | Breast-feeding is generally contraindicated |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; HbsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; HTLV, human T-lymphotropic virus.

Mothers should be encouraged to nurse at each breast at each feeding starting with the breast offered 2nd at the last feeding. It is not unusual for an infant to fall asleep after the 1st breast and refuse the 2nd. It is preferable to empty the 1st breast before offering the 2nd in order to allow complete emptying and therefore better milk production. Table 42-5 summarizes patterns of milk supply in the 1st week.

Table 42-5 PATTERNS OF MILK SUPPLY

| DAY OF LIFE | MILK SUPPLY |

|---|---|

| Day 1 | Some milk (~5 mL) may be expressed |

| Days 2-4 | Lactogenesis, milk production increases |

| Day 5 | Milk present, fullness, leaking felt |

| Day 6 onward | Breasts should feel “empty” after feeding |

Adapted from Neifert MR: Clinical aspects of lactation: promoting breastfeeding success, Clin Perinatol 26:281–306, 1999.

New mothers should be instructed about infant hunger cues, correct nipple latch, positioning of the infant on the breast, and feeding frequency. It is also suggested that a physician or a lactation expert observe a feeding to evaluate positioning, latch, milk transfer and maternal responses, and infant satiety. Attention to these issues during the birth hospitalization allows dialogue with the mother and family and can prevent problems that could occur with improper technique or knowledge of breast-feeding. As part of the discharge teaching process, issues surrounding infant feeding, elimination patterns, breast engorgement, basic breast care, and maternal nutrition should be discussed. A follow-up appointment is recommended within 24-48 hr after hospital discharge.

Nipple Pain

Nipple pain is one of the most common complaints of breast-feeding mothers in the immediate postpartum period. Poor infant positioning and improper latch are the most common reasons for nipple pain beyond the mild discomfort felt early in breast-feeding. If the problem persists and the infant refuses to feed, consideration needs to be given to nipple candidiasis, and both mother and baby should be treated if candidiasis is found. In some cases, especially if accompanied by engorgement, it may be necessary to express milk manually until healing has occurred.

Engorgement

In the 2nd stage of lactogenesis, physiologic fullness of the breast occurs. If the breasts are firm, overfilled, and painful, the cause may be incomplete removal of milk due to poor breast-feeding technique or other reasons such as infant illness. Frequent breast-feeding or, in some cases, manual milk expression before breast-feeding may be required.

Mastitis

Mastitis occurs in 2-3% of lactating women and is usually unilateral, manifesting with localized warmth, tenderness, edema, and erythema after the 2nd postdelivery week. Sudden onset of breast pain, myalgia, and fever with fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and headache can also occur. Organisms implicated in mastitis include Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, group A streptococcus, Haemophilus influenzae, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Bacteroides spp. Diagnosis is confirmed by physical examination. Oral antibiotics and analgesics, while promoting breast-feeding or emptying of the affected breast, usually resolve the infection. A breast abscess is a less-common complication of mastitis, but it is a more serious infection that requires intravenous antibiotics as well as incision and drainage, along with temporary cessation of feeding from that breast.

Milk Leakage

Milk leakage is a common event in which milk is involuntarily lost from the breast either in response to breast-feeding on the opposite side or as a reflex in response to other stimuli, such as an infant’s cry. Milk leakage usually resolves spontaneously as lactation proceeds.

Inadequate Milk Intake

Insufficient milk intake, dehydration, and jaundice in the infant can surface after the first 48 hr of life. The infant might cry or be lethargic and have delayed stooling, decreased urine output, weight loss >7% of birth weight, hypernatremic dehydration, and increased hunger. Insufficient milk intake may be due to insufficient milk production or failure of established breast-feeding, but it can also result from health conditions in the infant that prevent proper breast stimulation. Parents should be counseled that breast-fed neonates must feed a minimum of 8 times per day. Careful attention to prenatal history can identify maternal factors that may be associated with this problem, for example, failure of breasts to enlarge during pregnancy or within the first few days after delivery. Direct observation of breast-feeding can help identify improper technique. If a large volume of milk is expressed manually after breast-feeding, then the infant might not be extracting enough milk, eventually leading to decreased milk output. Late preterm infants (34-36 wk) are at risk for insufficient milk syndrome because of poor suck and swallow patterns or medical issues.

Jaundice

Breast-feeding jaundice is a common reason for hospital readmission of healthy breast-fed infants and is largely related to insufficient fluid intake (Chapter 96.3). It may also be associated with dehydration and hypernatremia. Breast milk jaundice causes persistently high serum indirect bilirubin in a thriving healthy baby. Jaundice generally declines in the 2nd wk of life. Infants with severe or persistent jaundice should be evaluated for problems such as galactosemia, hypothyroidism, urinary tract infection, and hemolysis before ascribing the jaundice to breast milk that might contain inhibitors of glucuronyl transferase or enhanced absorption of bilirubin from the gut. Persistently high bilirubin can require changing from breast milk to infant formula for 24-48 hr and/or phototherapy without cessation of breast-feeding. Breast-feeding should resume after the decline in serum bilirubin. Parents should be reassured and encouraged to continue collecting breast milk during the period when the infant is taking formula.

Collecting Breast Milk

The pumping of breast milk is a common practice when the mother and baby are separated, such as when the mother returns to work or when there is an illness or hospitalization of the mother or infant that precludes breast-feeding. Good handwashing and hygiene should be emphasized. Electric breast pumps are more efficient and better tolerated by mothers than mechanical pumps or manual expression. Collection kits should be rinsed, cleaned with hot soapy water, and air dried after every use. Glass or plastic containers should be used to collect the milk, and milk should be refrigerated and then used within 48 hr. Expressed breast milk can be frozen and used for up to 6 mo. Milk should be thawed rapidly by holding under running tepid water and used completely within 24 hr after thawing. Milk should not be microwaved.

Growth of the Breast-fed Infant

The rate of weight gain of the breast-fed infant differs from that of the formula-fed infant, and the infant’s risk for excess weight gain during late infancy may be associated with bottle feeding. Some of the differences in weight gain are explained by the use of growth charts derived from predominantly formula-fed children, and several studies suggest that the growth pattern of the population of breast-fed infants should be considered the norm. The WHO, has published a growth reference based on the growth of healthy breast-fed infants through the 1st yr of life. The new standards (http://www.who.int/childgrowth) are the result of a study in which >8,000 children were selected from 6 countries. The infants were selected based on healthy feeding practices (breast-feeding), good health care, high socioeconomic status, and nonsmoking mothers, so that they reflect the growth of breast-fed infants in the optimal conditions and can be used as prescriptive rather than normative curves. Charts are available for growth monitoring from birth to age 6 yr. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention now recommends use of these charts for infants 0 to 23 months of age.

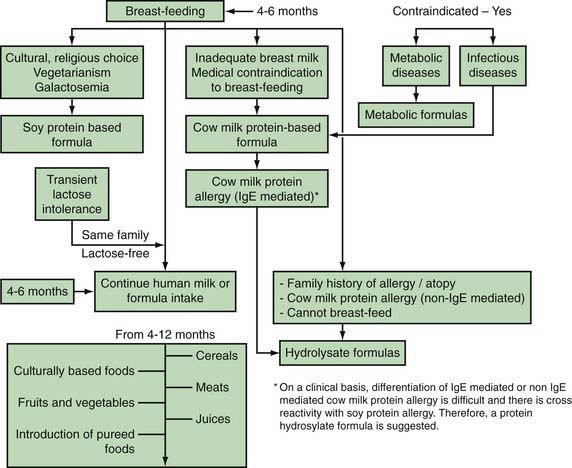

Formula Feeding (Fig. 42-1)

Most women make their feeding choices for their infant early in pregnancy. In a U.S. survey, although 83% of respondents initiated breast-feeding, the percentage who continued to breast-feed declined to 50% at 6 mo. Fifty-two percent of infants received formula while in the hospital and by 4 mo 40% had consumed other foods as well. Despite efforts to promote breast-feeding and discourage complementary foods before 4 mo of age, supplementing breast-feeding with infant formula and early introduction of complementary foods remain common in the USA. Indications for the use of infant formula are as a substitute or a supplement for breast milk or as a substitute for breast milk when breast milk is medically contraindicated by maternal (see Table 42-4) or infant factors.

Figure 42-1 Feeding algorithm for term infants.

(From Gamble Y, Bunyapen C, Bhatia J: Feeding the term infant. In Berdanier CD, Dwyer J, Feldman EB, editors: Handbook of nutrition and food, Boca Raton, FL, 2008, CRC Press, Taylor and Francis Group, pp 271–284, Fig. 15-3.)

Infant formulas marketed in the USA are safe and nutritionally adequate as the sole source of nutrition for healthy infants for the first 4-6 mo of life. Infant formulas are available in ready-to-feed, concentrated liquid or powder forms. Ready-to-feed products generally provide 20 kcal/30 mL (1 oz) and approximately 67 kcal/dL. Concentrated liquid products when diluted according to instructions provide a preparation with the same concentration. Powder formulas come in single or multiple servings and when mixed according to instructions will result in similar caloric density.

Although infant formulas are manufactured in adherence to good manufacturing practices and are inspected by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), there are potential issues. Powder preparations are not sterile, and although the number of bacterial colony-forming units per gram of formula is generally lower than allowable limits, outbreaks of infections with Enterobacter sakazakii have been documented, especially in premature infants. The powder preparations can contain other coliform bacteria but have not been linked to disease in healthy term infants. Care also needs to be taken in following the mixing instructions to avoid over or under dilution, using water either boiled or sterilized, and using the specific scoops provided by the manufacturer, because scoop sizes vary. Well water needs to be tested regularly for bacteria and toxin contamination. Municipal water can contain variable concentrations of fluoride, and if the concentrations are high, bottled water that is defluoridated should be used to avoid toxicity.

Parents should be instructed to use proper handwashing techniques when preparing formula or feeding the infant. Guidance to follow written instructions for storage should also be given. Once opened, ready-to-feed and concentrated liquid containers can be covered with aluminum foil or plastic wrap and stored in the refrigerator for no longer than 48 hr. Powder formula should be stored in a cool, dry place; once opened, cans should be covered with the original plastic cap or aluminum foil, and the powdered product can be used for up to 4 wk. Prepared formula stored in the refrigerator should be warmed by placing the container in warm water for ~5 min; similar to breast milk, formula should not be heated in a microwave, because the formula can be heated unevenly and result in burns despite appearing to be at the right temperature when the surface is tested.

Formula feedings should be ad libitum, with the goal of achieving growth and development to the child’s genetic potential. The usual intake to allow a weight gain of 25-30 g/day will be 140-200 mL/kg/day in the first 3 mo of life. Between 3 and 6 mo of age and between 6 and 12 mo of age, the rate of weight gain declines. The protein and energy content of infant formulas in the USA for term infants is ~2.1 g/100 kcal and 67 kcal/dL. No recommendations have been made for follow-up or weaning formulas, although these are available and marketed.

If feedings are adequate and weight, length, and head circumference trajectories are appropriate, then infants do not need additional water, unless dictated by high environmental temperature. Vomiting and spitting up are common, and when weight gain and general well-being are noted, no change in formula is necessary. Most infants thrive on cow’s milk protein–based formulas, although some infants exhibit intolerance or allergy to cow’s milk protein.

In addition to complementary foods introduced between 4 and 6 mo of age, continued breast-feeding or the use of infant formula for the entire 1st year of life should be encouraged. Whole cow’s milk should not be introduced until 12 mo of age. In children between 12 and 24 mo of age for whom overweight or obesity is a concern or who have a family history of obesity, dyslipidemia, or cardiovascular disease, the use of reduced-fat milk would be appropriate.

Cow’s Milk Protein–Based Formulas

Intact cow’s milk–based formulas in the USA contain a protein concentration varying from 1.45 to 1.6 g/dL, considerably higher than in mature breast milk (~1 g/dL). The whey : casein ratio varies from 18 : 82 to 60 : 40; one manufacturer markets a formula that is 100% whey. The predominant whey protein is β-globulin in bovine milk and α-lactalbumin in human milk. This and other differences between human milk and bovine milk–based formulas result in different plasma amino acid profiles in infants on different feeding patterns, but a clinical significance of these differences has not been demonstrated.

Plant or a mixture of plant and animal oils are the source of fat in infant formulas, and fat provides 40-50% of the energy in cow’s milk–based formulas. Fat blends are better absorbed than dairy fat and provide saturated, monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). All infant formulas are supplemented with long-chain PUFAs, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and arachidonic acid (ARA) at varying concentrations. ARA and DHA are found at varying concentrations in human milk and vary by geographic region and maternal diet. No studies in term infants have found a negative effect of DHA and ARA supplementation, but some studies have demonstrated positive effects on visual acuity and neurocognitive development. A critical review concluded that there are no consistent effects of long-chain PUFAs (LCPUFAs) on visual acuity in term infants. A Cochrane review concluded that routine supplementation of milk formula with LCPUFAs to improve the physical, neurodevelopmental, or visual outcomes of infants born at term cannot be recommended based on the current evidence. DHA and ARA derived from single-cell microfungi and microalgae are classified as generally recognized as safe for use in infant formulas at approved concentrations and ratios.

Lactose is the major carbohydrate in mother’s milk and in standard cow’s milk–based infant formulas for term infants. Formulas for older infants might also contain modified starch or other complex carbohydrates.

Soy Formulas

Soy protein–based formulas on the market are all free of cow’s milk protein and lactose and provide 67 kcal/dL. They meet the vitamin, mineral, and electrolyte guidelines from the AAP and the FDA for feeding term infants. The protein is a soy isolate supplemented with L-methionine, L-carnitine, and taurine to provide a protein content of 2.45-2.8 g per 100 kcal or 1.65-1.9 g/dL.

The quantity of specific fats varies by manufacturer and is usually similar to the manufacturer’s corresponding cow’s milk–based formula. The fat content is 5.0-5.5 g per 100 kcal or 3.4-3.6 g/dL. The oils used include soy, palm, sunflower, olein, safflower, and coconut. DHA and ARA are now added routinely.

In term infants, although soy protein–based formulas have been used to provide nutrition resulting in normal growth patterns, there are few indications for use in place of cow’s milk–based formula. These indications include galactosemia and hereditary lactase deficiency, because soy–based formulas are lactose-free; and situations in which a vegetarian diet is preferred. Most previously well infants with acute gastroenteritis can be managed after rehydration with continued use of mother’s milk or cow’s milk–based formulas and do not require lactose-free formula, such as soy-based formula. However, soy protein–based formulas may be indicated when documented secondary lactose intolerance occurs. Soy protein–based formulas have no advantage over cow’s milk protein–based formulas as a supplement for the breast-fed infant, unless the infant has one of the indications noted previously. The routine use of soy protein–based formula has no proven value in the prevention or management of infantile colic, fussiness, or atopic disease. Infants with documented cow’s milk protein–induced enteropathy or enterocolitis often are also sensitive to soy protein and should not be given isolated soy protein–based formula. They should be provided formula derived from extensively hydrolyzed protein or synthetic amino acids. Soy formulas can contain phytoestrogens, which have increased caution for their use in infants.

Protein Hydrolysate Formula

Protein hydrolysate formulas may be partially hydrolyzed, containing oligopeptides with a molecular weight of <5000 d, or extensively hydrolyzed, containing peptides with a molecular weight <3000 d. Partially hydrolyzed proteins have fat blends similar to cow’s milk–based formulas, and carbohydrates are supplied by corn maltodextrin or corn syrup solids. Because the protein is not extensively hydrolyzed, these formulas should not be fed to infants who are allergic to cow’s milk protein. In studies of infants who are at high risk of developing atopic disease and who are not breast-fed exclusively for 4-6 mo, there is modest evidence that atopic dermatitis may be delayed or prevented in early childhood by the use of extensively or partially hydrolyzed formulas, compared with cow’s milk formula. Comparative studies of the various hydrolyzed formulas have also indicated that not all formulas have the same protective benefit. Extensively hydrolyzed formulas may be more effective than partially hydrolyzed in preventing atopic disease. Extensively hydrolyzed formulas are the preferred formulas for infants intolerant to cow’s milk or soy proteins. These formulas are lactose free and can include medium-chain triglycerides, making them useful in infants with gastrointestinal malabsorption due to cystic fibrosis, short gut syndrome, and prolonged diarrhea.

Amino Acid Formulas

Amino acid formulas are peptide-free formulas that contain mixtures of essential and nonessential amino acids. They are specifically designed for infants with dairy protein allergy who failed to thrive on extensively hydrolyzed protein formulas. The use of amino acid formulas to prevent atopic disease has not been studied.

Complementary Feeding

The timely introduction of complementary foods (all solid foods and liquid foods other than breast milk or formula, also called weaning foods or beikost) during infancy is necessary to enable transition from milk feedings to other foods and is important for nutritional and developmental reasons (Table 42-6). The dilemmas of the weaning period are different in different societies. The ability of exclusive breast-feeding to meet macronutrient and micronutrient requirements becomes limiting with increasing age of the infant. Current WHO recommendations on the age at which complementary food should be introduced are based on the optimal duration of exclusive breast-feeding. A WHO-commissioned systematic review of the optimal duration of exclusive breast-feeding compared outcomes with exclusive breast-feeding for 6 vs 3-4 mo. The review concluded that there were no differences in growth between the 2 durations of exclusive breast-feeding. Another systematic review concluded that there was no compelling evidence to change the recommendations for starting complementary foods at 4-6 mo. The AAP Pediatric Nutrition Handbook also states that there is no significant harm associated with introduction of complementary foods at 4 mo of age and no significant benefit from exclusive breast-feeding for 6 mo in terms of growth, zinc and iron nutriture, allergy, or infections. The European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition considers that exclusive breast-feeding for ~6 mo is desirable, but that the introduction of complementary foods should not occur before 17 weeks (~4 mo) and should not be delayed beyond 26 weeks (~6 mo).

Evidence for the optimal timing for introducing specific complementary foods is lacking and is largely based on consensus and traditions. Practices vary widely among regions and cultures. Ideally, complementary foods are combined with human milk or formula to provide the nutrients required for appropriate growth. Current complementary feeding practices largely meet infants’ energy and nutrient needs. Because some complementary foods are more nutritionally appropriate than others to complement breast milk or infant formula, improved evidence-based guidelines about types, quantities, and timing of introducing complementary foods would be desirable. For example, the Feeding and Toddlers Study collected data on the food consumption patterns of U.S. infants and toddlers and showed that nearly all infants ≤12 mo consumed some form of milk every day; more infants >4 mo consumed more formula than human milk, and by 9-11 mo of age 20% consumed whole cow’s milk and 25% consumed nonfat or reduced-fat milk. These patterns are somewhat similar to patterns in Denmark, Sweden, and Canada, where whole cow’s milk can be introduced between 9 and 10 mo of age.

The most commonly fed complementary foods between 4 and 11 mo are infant cereals. Nearly 45% of infants between 9 and 11 mo consume noninfant cereals. Infant eating patterns also varied, with up to 61% of infants 4-11 mo of age consuming no vegetables. Among those who consumed vegetables, French fries were one of the common foods fed as vegetables.

The AAP provides the following recommendations for initiating complementary foods (Pediatric Nutrition Handbook, 6th edition):

The period of introducing increasingly diverse complementary foods gives the opportunity to provide adequate nutrition or to increase the risk of over- or underfeeding. Overconsumption of energy-dense complementary foods can support excessive weight gain in infancy, resulting in an increased risk of obesity in childhood.

Feeding Toddlers and Preschool-Age Children

The 2nd yr of life is a period when eating behavior and healthful habits can be established and is often a confusing and anxiety-generating period for parents. Growth after the 1st yr slows down, motor activity increases, and appetites decrease. Birth weight triples during the 1st yr of life and quadruples by 2 yr of age, reflecting this slowing in growth velocity. Birth length increases during the 1st yr of life and doubles by 4 yr of age. Eating behavior is erratic, and the child appears distracted as he or she explores the environment. Children consume a limited variety of foods and often only “like” a particular food for a period of time and then reject the favored food. These concerns need to be addressed in the context of growth and development and with appropriate nutritional counseling. Demonstrating adequate growth and providing guidance about behavior and eating habits will go a long way in allaying concerns of parents and other caregivers. Important goals of early childhood nutrition are to foster healthful eating habits and to offer foods that are developmentally appropriate, while not always giving in to every child’s requests, such as for sweets or French fries.

Feeding Practices

The period starting after 6 mo until 15 mo is characterized by the acquisition of self-feeding skills because the infant can grasp finger foods, learn to use a spoon, and eat soft foods (Table 42-7). Around 15 mo, the child learns to feed himself or herself and to drink from a cup, messy as that may be. Infants may still breast-feed or desire formula bottle feeding, but bedtime bottles should be discouraged because of the association with dental caries. Even breast-fed babies can develop caries; therefore, drinking juices and other sugared drinks from a bottle should be discouraged in all infants at all times. In the 2nd yr of life, self-feeding becomes a norm and provides the opportunity for the family to eat together with less stress. Self-feeding allows the child to limit his or her intake while also observing parental reactions to the child’s eating behavior. Encouraging positive eating behaviors and ignoring negative ones unless they jeopardize the health and safety of the infant should be the family’s goal.

Table 42-7 FEEDING SKILLS BIRTH TO 36 MONTHS

| AGE (mo) | FEEDING/ORAL SENSORIMOTOR |

|---|---|

| Birth to 4-6 | |

| 6-9 (transition feeding) | |

| 9-12 | |

| 12-18 | |

| >18-24 | |

| 24-26 |

Modified from Udall Jr JN: Infant feeding: initiation, problems, approaches, Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 37:369–408, 2007.

The child should progress from soft, nonsticky foods or foods with small particle size (to avoid choking and gagging) to prepared table foods with the same precautions. At this stage, the child is not capable of completely chewing and swallowing foods, and foods with a choking risk, such as hard candies and peanuts, should be avoided. Caregivers should always be vigilant and present during feeding, and the child should be placed in a high chair. The AAP and other organizations discourage eating in the presence of distractions such as television or eating in a car where an adult cannot adequately supervise or observe the child.

A newborn infant can already discriminate between sweet and sour. This same phenomenon is observed in infancy and early childhood as a preference for sweetened foods and beverages. A new food has to be offered multiple times before being considered rejected by the child. This, as well as reluctance to accept new foods, is a common developmental phase, and persistence and patience are the keys to successful feeding.

Toddlers eat or need to eat 5-7 times a day, and parents need to capitalize on these habits by offering tasty and healthful snacks. Milk continues to be an important source of nutrition, because it includes important nutrients such as vitamin D. Guidelines for vitamin D supplementation recommend a daily vitamin D intake of 400 IU/day for all infants beginning in the first few days of life, children, and adolescents who are ingesting <1000 mL/day of vitamin D-fortified milk or formula. About 2/3 of toddlers consume fruits and vegetables, and more than 75% consume a serving of vegetables on any given day, with French fries being the most commonly consumed vegetable. Preschool children also lag behind current recommendations for the number of servings of fruits, vegetables, and fiber, whereas intakes of food with fat and added sugar are high.

Feeding infants and children is a challenge, and there is no one right way to nurture a child. It takes education, encouragement, and patience to go through this period, and the medical home for the child plays a very important role in supporting the family-infant dyad.

Eating in the Daycare Setting

Many U.S. toddlers and preschool children attend daycare and receive meals and snacks in this setting. There is a wide variation in the quality of the food offered and the level of supervision during meals. Parents are encouraged to assess the quality of the food served at daycare by asking questions, visiting the center, and taking part in parents’ committees. Pediatricians should also become familiar with the quality of daycare centers in their regions. Free or reduced-price snacks and meals are provided in daycare centers of low- and medium-income communities through the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Child and Adult Care Food Program. Participating programs are required to provide meals and snacks that meet the dietary guidelines, also set by the USDA, and therefore guarantee a level of food quality. Because the reimbursement is typically low, many daycare centers still struggle in providing high-quality meals and snacks through the day.

Feeding School-Age Children and Adolescents

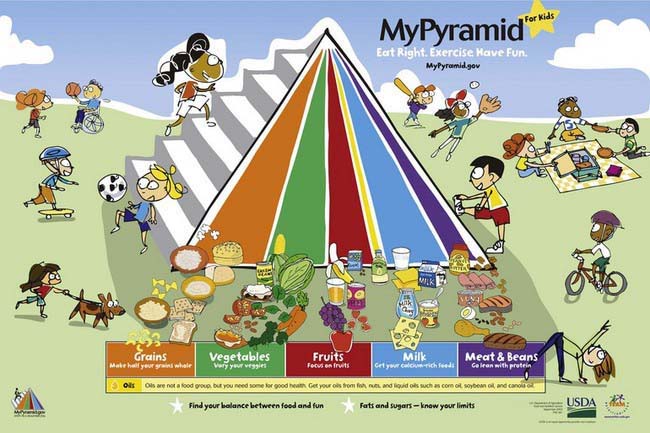

MyPyramid

Most U.S. professional organizations and governmental agencies recommend the use of the USDA MyPyramid (www.mypyramid.gov) as a basis for building an optimal diet for children and adolescents. MyPyramid is based on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. A personalized eating plan based on these guidelines provide, on average over a few days, all the essential nutrients necessary for health and growth, while limiting nutrients associated with chronic disease development. MyPyramid is aimed at the general public and differs from previous versions of the food pyramid in many ways. The intent is to primarily use MyPyramid as an Internet interactive tool that allows customization of recommendations, based on age, sex, physical activity, and, for some populations, weight and height. Print material is also available for families without Internet access.

Recommendations based on MyPyramid are given within 5 food groups (grains, vegetables, fruits, milk, and meat and beans) plus oils, with the general recommendations to eat, over time, a variety of foods within each food group. The graphic representation (Fig. 42-2) of slices symbolizes the average number of servings that should be consumed daily from each food group. In addition to these food groups, MyPyramid offers recommendations for physical activity to achieve a healthful energy balance. MyPyramid also provides information on discretionary calories, which are the foods that are not included in MyPyramid guidelines because of their low nutritional value, such as sweetened beverages, sweetened bakery products, or higher-fat meats. It should be noted that a diet based on MyPyramid, in order to provide all the necessary nutrients, allows a very small amount of discretionary calories available each day.

Figure 42-2 MyPyramid Food Guide.

(From U.S. Department of Agriculture: mypyramid.gov [website]. http://www.mypyramid.gov/. Accessed May 14, 2010.)

In the USA and in an increasing number of other countries the vast majority of children and adolescents do not consume a diet that follows the recommendations of MyPyramid. In general, intake of discretionary calories is much higher than recommended, with frequent consumption of sweetened beverages (soda, juice drinks, iced tea, sport drinks), snack foods, high-fat meat (bacon, sausage), and high-fat dairy products (cheese, ice cream). Intake of dark green and orange vegetables (as opposed to fried white potatoes), whole fruits, reduced-fat dairy products, and whole grain is typically lower than recommended. Furthermore, unhealthful eating habits—such as larger-than-recommended portion sizes; food preparation that adds fat, sugar, or salt; skipping breakfast and/or lunch; grazing; or following fad diets—is prevalent and associated with a poorer diet quality. Therefore, MyPyramid offers a helpful and customer-friendly tool to assist pediatricians counseling families on optimal eating plans for short- and long-term health.

Eating at Home

At home, much of what children and adolescents eat is under the control of their parents. Typically, parents shop for groceries and they control, to some extent, what food is available in the house. It has been demonstrated that modeling of healthful eating behavior by parents is a critical determinant of the food choices of children and adolescents (Table 42-8). Therefore, pediatric counseling to improve diet should include guiding parents in using their influence to make healthier food choices available and attractive at home.

Table 42-8 FEEDING GUIDELINES FOR PARENTS

Adapted from Kleinman RE and the AAP Committee on Nutrition: Pediatric nutrition handbook, ed 6, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2009, American Academy of Pediatrics.

Regular family meals sitting at a table, as opposed to eating alone, in the living room, or watching television, have been associated with improved diet quality, perhaps because of increased opportunities for positive parenting during meals. Such an ideal situation is recommended but a challenge for many families who, with busy schedules and other stressors, are unable to provide such a setting. Pediatricians should work with families to set realistic goals around these eating issues. Another parenting challenge is to control the excess appetite of some children and adolescents. Useful strategies, when the child is still hungry after a meal, include a 15- to 20-min pause before a 2nd serving or offering foods that are insufficiently consumed, such as vegetables, whole grains, or fruits.

Eating at School

Food quality and availability of healthy options vary greatly among U.S. schools. Schools that participate in federally reimbursed lunch or breakfast programs are required to comply with minimum standards for those meals, but regulation of other foods and beverages available in the school are less consistent. These competitive foods, often sold through vending machines, are available through exclusivity contracts with food and beverage companies that represent significant sources of revenue for many schools for funding important programs. Low reimbursement levels from federal programs, unavailable or inadequate cooking facilities, insufficient training of school cafeteria staff, and competing academic requirements are additional barriers to offering healthy nutrition in schools. This is an important issue, because most U.S. children take 1 or 2 meals a day in school. Pediatricians and parents should therefore keep themselves informed of the school’s nutrition policies and menus in their districts and advocate for improved standards. Where the quality of school nutrition is problematic, a practical alternative is to suggest that children pack their own lunch from home.

Eating Out

The number of meals eaten outside the home or brought home from take-out restaurants has increased in all age groups of the U.S. population. The increased convenience of this meal pattern is undermined by the generally lower nutritional value of the meals, compared to home-cooked meals. Typically, meals consumed or purchased in fast-food or casual restaurants are of large portion size, are dense in calories, and contain large amounts of saturated and trans fats, salt, and sugar and low amounts of whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. Although an increasing number of restaurants offer healthier alternatives, the vast majority of what is consumed at restaurants does not fit MyPyramid. Parents can use these opportunities to teach and model healthful choices within the choices offered.

With increasing age, an increasing number of meals and snacks are also consumed during peer social gatherings at friends’ houses and parties. When a large part of a child’s or adolescent’s diet is consumed on these occasions, the diet quality can suffer, because food offerings are typically of low nutritional value. Parents and pediatricians need to guide teens in navigating these occasions while maintaining a healthful diet and enjoying meaningful social interactions. These occasions often are also opportunities for teens to consume alcohol; therefore, adult supervision is important.

Nutrition Issues of Importance across Pediatric Ages

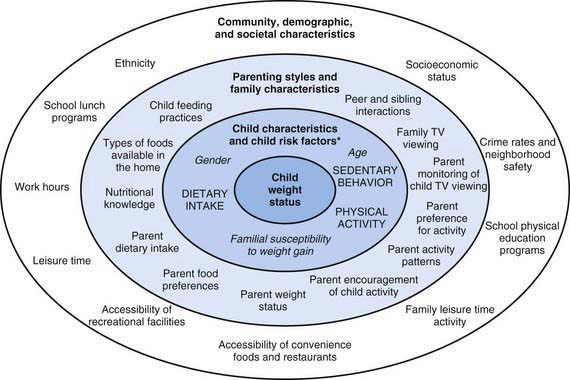

Food Environment

Most families have some knowledge of how to optimize nutrition and intend to provide their children with a healthful diet. The discrepancy between this fact and the actual quality of the diet consumed by U.S. children is often explained by difficulties and barriers for families to make healthful food choices. Because the final food choice is made by individual children or their parents, interventions to improve diet have focused on individual knowledge and behavior changes, but these have had limited success. One of the main determinants of food choice is taste, but other factors also influence these choices. One of the most useful conceptual frameworks to understand the child’s food environment in the context of obesity illustrates the variety and levels of the determinants of individual food and physical activity choices. Many of these determinants are not under the direct control of individual children or parents (Fig. 42-3). Understanding the context of food and lifestyle choices helps in understanding lack of changes or “poor compliance” and can decrease the frustration often experienced by the pediatricians who might “blame the victim” for behavior that is not entirely under their control.

Figure 42-3 A conceptual framework of the context of food and lifestyle choices. *Child risk factors (shown in upper case lettering) refer to child behaviors associated with the development of overweight. Characteristics of the child (shown in italic lettering) interact with child risk factors and contextual factors to influence the development of overweight (i.e., moderator variables).

(From Davison KK, Birch LL: Childhood overweight: a contextual model and recommendations for future research, Obes Rev 2:159–171, 2001.

Marketing and advertising of food to children is a particularly illustrative aspect of the food environment. Marketing includes strategies as diverse as shelf placements, association of cartoon characters with food products, coupons, and special offers or pricing, all of which influence food choices. Television advertising is an important part of how children and adolescents hear about food, with an estimated 40,000 TV commercials seen by the average U.S. child, many of which are for food, as compared to the few hours of nutrition education they receive in school. Additional food advertisement increasingly occurs as brand placement in movies and TV shows, on websites, and even video games.

Using Food as Reward

It is a prevalent habit to use food as a reward or sometimes withdraw food as punishment at various ages and in various settings. Most parents use this practice occasionally, and some use it almost systematically, starting at a young age. The practice is also commonly used in other settings where children spend time, such as daycare, school, or even athletic settings. Although it might be a good idea to limit some unhealthy but desirable food categories to special occasions, using food as a reward is problematic. Limiting access to some foods and making its access contingent on a particular accomplishment increases the desirability of that type of food. Conversely, encouraging the consumption of some foods renders them less desirable. Therefore, phrases such as “finish your vegetables, and you will get ice cream for dessert” can result in establishing unhealthy eating habits once the child has more autonomy in food choices. Parents should be counseled on such issues and encouraged to choose items other than food as reward, such as toys or sporting equipment, special family events, or collectable items. Daycare and school teachers should also be discouraged from using food as a reward or to withhold food as punishment.

Cultural Considerations in Nutrition and Feeding

Food choices, food preparation, eating patterns, and infant feeding practices all have very deep cultural roots. In fact, beliefs, attitudes, and practices surrounding food and eating are some of the most important components of cultural identity. Therefore, it is not surprising that in multicultural societies, great variability exists in the cultural characteristics of the diet. Even in a world where global marketing forces tend to reduce geographic differences in the types of food, or even brands, that are available, most families, especially during family meals at home, are still much influenced by their cultural background. Therefore, pediatricians should become familiar with the dietary characteristics of various cultures in their community, so that they can identify and address, in a nonjudgmental way and avoiding stereotypes, the likely nutritional issues related to the diet of their patients.

Many differences exist in infant-feeding practices as well. Even if many of these practices do not follow the usual recommendations, often based themselves more on tradition than science, they are compatible with healthy growth and should only be challenged when clear evidence of their negative effects is available.

Vegetarianism

Vegetarianism is the practice of following a diet that excludes meat (including game and slaughter by-products; fish, shellfish, and other sea animals; and poultry). There are several variants of the diet, some of which also exclude eggs and/or some products produced from animal labor, such as dairy products and honey. There are many different variations in vegetarianism:

A generic expression often used for vegetarianism and veganism is “plant-based diets.” Other dietary practices commonly associated with vegetarianism include fruitarian diet (fruits, nuts, seeds, and other plant matter gathered without harm to the plant); su vegetarian diet (a diet that excludes all animal products as well as onion, garlic, scallions, leeks, or shallots); a macrobiotic diet (whole grains and beans and in some cases fish); and raw vegan diet (fresh and uncooked fruits, nuts, seeds, and vegetables).

Vegetarianism is considered a healthful and viable diet, and both the American Dietetic Association and the Dietitians of Canada have found that a properly planned vegetarian diet can satisfy the nutritional goals for all stages of life. Various reports find lower risks of cancer and ischemic heart disease. These authoritative bodies have stated that “Vegetarian diets offer a number of nutritional benefits, including lower levels of saturated fat, cholesterol, and animal protein, as well as higher levels of carbohydrates, fiber, magnesium, potassium, folate, and antioxidants such as vitamins C and E and phytochemicals.” Vegetarians also tend to have lower body mass index, lower cholesterol, and lower blood pressure than nonvegetarians.

Specific nutrients of concern in vegetarian diets include:

Organic Foods

The increasing interest in using organic foods, especially to feed children, results in frequent questions to pediatricians. Unfortunately, the scientific basis available to answer these questions is slim, and no clear benefit or harm associated with organic food consumption has been clearly demonstrated. Children consuming organic foods have lower or no detectable levels of pesticides in their urine compared to those consuming nonorganic foods. Some families also choose organic foods for their perceived environmental benefit more than for the human health reasons. As the cost of these foods is generally higher than the cost of other food, a prudent approach is to explain to families that the scientific basis for choosing organic foods is limited, but if it is their preference and they can afford the added cost, there is no reason not to eat organic foods.

Nutrition as Part of Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Functional Foods, Dietary Supplements, Vitamin Supplements, and Botanical and Herbal Products

The use of nutrition or nutritional supplements as complementary or alternative medicine is increasing, despite very limited data on safety and efficacy, especially in children. Many parents assume that if a food or supplement is natural or organic, then there is no potential for risk and that there might be some potential for benefits. We know, of course, that this is not the case, and the adverse effects of some dietary supplements have come to light, including evidence of severe adverse effects. However, it is difficult for pediatricians using evidence-based messages to compete against the aggressive marketing of food supplements to families of healthy and chronically ill children; through the Internet, television shows, and magazines; or simply against the word-of-mouth or advice from people without a scientific background or with significant conflicts of interest. One reason to recommend caution to parents when it comes to dietary supplements, including botanical and herbal products, is that in the USA, unlike medications, these products are not evaluated for safety and efficacy before marketing and do not undergo the same level of quality control as medications. The potential for adverse effects or simply for inefficacy is therefore high.

Some dietary components, either available as supplements or within so-called functional foods, have been more carefully evaluated. These include emerging evidence for safety and efficacy of using pre- and probiotics for various gastrointestinal conditions, plant sterols for dyslipidemia, fish oils for elevated triglycerides, or an elemental diet for inflammatory bowel disease.

Pediatricians are often asked by parents if their children need to receive a daily multivitamin. Unless the child follows a particular diet that may be poor in one or more nutrients for health, cultural, or religious reasons, or if the child has a chronic health condition that puts him or her at risk for deficiency in one or more nutrients, multivitamins are not indicated. A diet that follows the guidelines of MyPyramid contains sufficient nutrients to support healthy growth. Of course, many children do not follow all the guidelines of MyPyramid, and parents and pediatricians may be tempted to use multivitamin supplements just to make sure that nutrient deficiencies are avoided. The problem with this approach is that multivitamin supplements do not provide all the nutrients that are necessary for good health, such as fiber or some of the antioxidants contained in food. Use of a daily multivitamin supplement can result in a false impression that the child’s diet is complete and in decreased efforts to meet dietary recommendations with food rather than the intake of supplements. As discussed in Chapter 41, the average U.S. diet provides more than a sufficient amount of most nutrients, including most vitamins. Therefore, multivitamins should not be routinely recommended.

The AAP recommends daily supplementation of 400 IU of vitamin D per day in all children who drink less than 1,000 mL/day of vitamin D–fortified milk, representing the majority of U.S. children and adolescents. In some specific populations of children at risk for deficiency, supplements of vitamin B12, iron, fat-soluble vitamins, or zinc may be considered.

Food Safety

Constantly keeping food safety issues in mind is an important aspect of feeding infants, children, and adolescents. In addition to choking hazards and food allergies, pediatricians and parents should be aware of food safety issues related to infectious agents and environmental contaminants. Food poisoning with infectious agents, either live bacteria or viruses or chemicals produced by these infectious agents, are most common with food consumed raw or undercooked, such as oysters, beef, eggs, and tomatoes, or cooked foods that have not been handled or stored properly. The specific infectious agents involved in food poisoning are described in Chapter 332. A good source of information for patients and parents can be found at www.foodsafety.gov.

Many chemical contaminants, such as heavy metals, pesticides, and organic compounds, are present in various foods, usually in small amounts. Because of concerns regarding their child’s neurologic development and cancer risk, many questions arise from parents, especially after media coverage of specific isolated incidents. Pediatricians therefore need to become familiar with reliable sources of information, such as the websites of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the FDA, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). For example, a recurrent debate is the balance between the benefits of seafood for the growing brain and cardiovascular health and the risk of mercury contamination from consuming large predatory fish species.

Nutritional Programming

Emerging epidemiologic evidence suggests that early nutrition can have a long-term impact on adult health. It is well established that undernutrition in early life can exert a long-term impact in terms of reduced adult height and academic achievements, but other data suggest that intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is associated with adult cardiovascular risk factors and disease. Rapid weight gain in infancy, either following IUGR or a period of malnutrition, is associated with an increased risk for later obesity.

Preventive Nutrition Counseling in Pediatric Primary Care

An important part of the primary care well child visit focuses on nutrition and growth, because most families turn to pediatricians for guidance on child nutrition. Preventive nutrition is one of the cornerstones of preventive pediatrics and a critical aspect of anticipatory guidance. The first steps of nutrition counseling are nutritional status assessments, primarily done through growth monitoring and dietary intake assessment. Although dietary assessment is somewhat simple in infants who have a relatively monotonous diet, it is more challenging at older ages. Even the most sophisticated and time-consuming research tools of dietary assessments are imprecise. Therefore, the goals of dietary assessment in the primary care setting need to remain modest, including simply getting an idea of the eating patterns (time, location, environment) and usual diet by asking the parent to describe the child’s dietary intake on a typical day or in the last 24 hr. For more ambitious goals of dietary assessment, referral to a registered dietician with pediatric experience is recommended.

Once some understanding of the child’s usual diet has been acquired, existing or anticipated nutritional problems should be addressed, such as diet quality, dietary habits, or portion size. For a few nutritional problems, a lack of knowledge can be addressed with nutrition education, but most pediatric preventive nutritional issues, such as overeating or poor food choices, are not the result of lack of parents’ knowledge. Therefore, nutrition education alone is insufficient in these situations, and pediatricians need to acquire training in behavior-modification techniques or refer to specialists to assist their patients in making healthy choices more often. The physical, cultural, and family environments in which the child lives should be kept in mind at all times, so that nutrition counseling is relevant and changes are feasible.

One important aspect of nutrition counseling is providing families with sources of additional information and behavioral change tools. Although some handouts are available from government agencies, the AAP, and other professional organizations for families without Internet access, an increasing number of families rely on the Internet to find nutrition information. Therefore, pediatricians need to become familiar with commonly used websites so that they can point families to reliable and unbiased sources of information. Perhaps the most useful websites for reliable and unbiased nutrition information for children are the USDA MyPyramid website, the sites of the CDC, FDA, National Institutes of Health (NIH), and Institute of Medicine Food and Nutrition Board for government sources and the AAP, American Heart Association, and American Dietetic Association for professional organization resources. Pediatricians should also be aware of sites that provide biased or even dangerous information, so that they can warn families accordingly. Examples include dieting sites, sites that openly promote dietary supplements or other food products, and the sites of “nonprofit” organizations that are mainly sponsored by food companies or that have other social or political agendas.

Food Assistance Programs in the USA

Several programs exist in the USA to ensure sufficient and high-quality nutrition for children of families who cannot always afford optimal nutrition. One of the most popular federal programs is the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). This program provides nutrition supplements to a large proportion of pregnant women, postpartum women, and children up to their 5th birthday. One of its strengths is that in order to qualify, families need to regularly visit a WIC nutritionist, who can be a useful resource for nutritional counseling. Other popular programs include school lunches, breakfasts, and after-school meals, as well as daycare and summer nutrition programs. Lower-income families are also eligible for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as the Food Stamp Program. This program provides funds directly to families to purchase various food items in regular food stores.

Basnet S, Schneider M, Gazit A, et al. Fresh goat’s milk for infants: myths and realities—a review. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e973-e977.

Bhatia J, Greer F, Committee on Nutrition. Use of soy protein–based formulas in infant feeding. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1062-1068.

Cao Y, Calafat AM, Doerge DR, et al. Isoflavones in urine, saliva and blood of infants—data from a pilot study on the estrogenic activity of soy formula. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2009;19:223-234.

Cattaneo A. Promoting breast feeding in the community. BMJ. 2009;338:a2657.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Racial and ethnic differences in breastfeeding initiation and duration, by state—national immunization survey, United States, 2004–2008. MMWR. 2010;59:327-334.

Faith MS, Scanlon KS, Birch LL, et al. Parent-child feeding strategies and their relationships to child eating and weight status. Obes Res. 2004;12:1711-1722.

Gale CR, Marriott LD, Martyn CN, et al. Breastfeeding, the use of docosahexaenoic acid-fortified formulas in infancy and neuropsychological function in childhood. Arch Dis Child. 2010;98:174-179.

Gidding SS, Dennison BA, Birch LL, et al. Dietary recommendations for children and adolescents: a guide for practitioners: consensus statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2005;112:2061-2075.

Grummer-Strawn LM, Reinold C, Krebs NF. Use of World Health Organization and CDC growth charts for children aged 0-59 months in the United States. MMWR. 2010;59(rr09):1-15.

Grummer-Strawn LM, Scanlon KS, Fein SB. Infant feeding and feeding transitions during the first year of life. Pediatrics. 2008;122:S36-S42.

Hoddinott P, Tappin D, Wright C. Breast feeding. BMJ. 2008;336:881-887.

Isaacs EB, Fischl BR, Quinn BT, et al. Impact of breast milk on intelligence quotient, brain size, and white matter development. Pediatr Res. 2010;67:357-362.

Jenik AG, Vain NE, Gorestein AN, et al. Does the recommendation to use a pacifier influence the prevalence of breastfeeding? J Pediatr. 2009;155:350-354.

Kleinman RL, editor. Pediatric nutrition handbook, ed 6, Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009.

Kumanyika SK. Environmental influences on childhood obesity: ethnic and cultural influences in context. Physiol Behav. 2008;94:61-70.

Lanigan J. Breastfeeding, early growth, and later obesity. Obes Rev. 2007;8:51-54.

Lawrence RM, Pane CA. Human breast milk: current concepts of immunology and infectious diseases. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2007;37:1-44.

Mann J. Vegetarian diets. BMJ. 2009;339:b2507.

Mozaffarian D, Rim EB. Fish intake, contaminants, and human health—evaluating the risks and the benefits. JAMA. 2006;296:1885-1899.

Myers GJ, Davidson PW. Maternal fish consumption benefits children’s development. Lancet. 2007;369:537-538.

Stallings VA, Yaktine AL, Institute of Medicine (U.S.), Committee on Nutrition Standards for Foods in Schools. Nutrition standards for foods in schools: leading the way toward healthier youth. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007.

Udall JNJr. Infant feeding: initiation, problems, approaches. Curr Prob Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2007;37:369-408.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture, Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2005, ed 6. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 2005.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Primary care interventions to promote breastfeeding: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:560-564.

Victora CG. Nutrition in early life: a global priority. Lancet. 2009;374:1123-1125.

Wagner CL, Greer FR, the Section on Breastfeeding and Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of rickets and vitamin D deficiency in infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;122:1142-1152.

World Health Organization. Global strategy for infant and young child feeding (website). www.who.int/childgrowth. Accessed May 14, 2010