Chapter 69 Cold Injuries

The involvement of children and youth in snowmobiling, mountain climbing, winter hiking, and skiing places them at risk for cold injury. Cold injury may produce either local tissue damage, with the injury pattern depending on exposure to damp cold (frostnip, immersion foot, or trench foot), dry cold (which leads to local frostbite), or generalized systemic effects (hypothermia).

Pathophysiology

Ice crystals may form between or within cells, interfering with the sodium pump, and may lead to rupture of cell membranes. Further damage may result from clumping of red blood cells or platelets, causing microembolism or thrombosis. Blood may be shunted away from an affected area by secondary neurovascular responses to the cold injury; this shunting often further damages an injured part while improving perfusion of other tissues. The spectrum of injury ranges from mild to severe and reflects the result of structural and functional disturbance in small blood vessels, nerves, and skin.

Etiology

Body heat may be lost by conduction (wet clothing, contact with metal or other solid conducting objects), convection (wind chill), evaporation, or radiation. Susceptibility to cold injury may be increased by dehydration, alcohol or drug use, substance abuse, impaired consciousness, exhaustion, hunger, anemia, impaired circulation due to cardiovascular disease, and sepsis; it is also greater in very young or aged persons.

Hypothermia occurs when the body can no longer sustain normal core temperature by physiologic mechanisms, such as vasoconstriction, shivering, muscle contraction, and nonshivering thermogenesis. When shivering ceases, the body is unable to maintain its core temperature; when the body core temperature falls to <35°C, the syndrome of hypothermia occurs. Wind chill, wet or inadequate clothing, and other factors increase local injury and may cause dangerous hypothermia, even in the presence of an ambient temperature that is not <17-20°C (50-60°F).

Clinical Manifestations

Frostnip

Frostnip results in the presence of firm, cold, white areas on the face, ears, or extremities. Blistering and peeling may occur over the next 24-72 hr, occasionally leaving mildly increased hypersensitivity to cold for some days or weeks. Treatment consists of warming the area with an unaffected hand or a warm object before the lesion reaches a stage of stinging or aching and before numbness supervenes.

Immersion Foot (Trench Foot)

Immersion foot occurs in cold weather when the feet remain in damp or wet, poorly ventilated boots. The feet become cold, numb, pale, edematous, and clammy. Tissue maceration and infection are likely, and prolonged autonomic disturbance is common. This autonomic disturbance leads to increased sweating, pain, and hypersensitivity to temperature changes, which may persist for years. The treatment is largely prophylactic and consists of using well-fitting, insulated, waterproof, nonconstricting footwear. Once damage has occurred, patients must choose clothing and footwear that are more appropriate, dry, and well-fitting. The disturbance in skin integrity is managed by keeping the affected area dry and well-ventilated and by preventing or treating infection. Only supportive measures are possible for control of autonomic symptoms.

Frostbite

With frostbite, initial stinging or aching of the skin progresses to cold, hard, white anesthetic and numb areas. On rewarming, the area becomes blotchy, itchy, and often red, swollen, and painful. The injury spectrum ranges from complete normality to extensive tissue damage, even gangrene, if early relief is not obtained.

Treatment consists of warming the damaged area. It is important not to cause further damage by attempting to rub the area with ice or snow; initial warming, as in frostnip, may be tried. The area may be warmed against an unaffected hand, the abdomen, or an axilla during transfer of the patient to a facility where more rapid warming with a water bath is possible. If the skin becomes painful and swelling occurs, anti-inflammatory agents are helpful and an analgesic agent is necessary. Freeze and rethaw cycles are most likely to cause permanent tissue injury, and it may be necessary to delay definitive warming and apply only mild measures if the patient is required to walk on the damaged feet en route to definitive treatment. In the hospital, the affected area should be immersed in warm water (approximately 42°C), with care taken not to burn the anesthetized skin. Vasodilating agents, such as prazosin and phenoxybenzamine, may be helpful. Use of anticoagulants (heparin, dextran) has had equivocal results; results of chemical and surgical sympathectomy have also been equivocal. Oxygen is of help only at high altitudes. Meticulous local care, prevention of infection, and keeping the rewarmed area dry, open, and sterile provide optimal results. Recovery can be complete, and prolonged observation with conservative therapy is justified before any excision or amputation of tissue is considered. Analgesia and maintenance of good nutrition are necessary throughout the prolonged waiting period.

Hypothermia

Hypothermia may occur in winter sports when injury, equipment failure, or exhaustion decreases the level of exertion, particularly if sufficient attention is not paid to wind chill. Immersion in frozen bodies of water and wet wind chill rapidly produce hypothermia. As the core temperature of the body falls, insidious onset of extreme lethargy, fatigue, incoordination, and apathy occurs, followed by mental confusion, clumsiness, irritability, hallucinations, and finally, bradycardia. A number of medical conditions, such as cardiac disease, diabetes mellitus, hypoglycemia, sepsis, β-blocking agent overdose, and substance abuse, may need to be considered in a differential diagnosis. The decrease in rectal temperature to <34°C (93°F) is the most helpful diagnostic feature. Hypothermia associated with drowning is discussed in Chapter 67.

Prevention is a high priority. Of extreme importance for those who participate in winter sports is wearing layers of warm clothing, gloves, socks within insulated boots that do not impede circulation, and a warm head covering, as well as application of adequate waterproofing and protection against the wind. Thirty percent of heat loss for infants occurs from the head. Ample food and fluid must be provided during exercise. Those who participate in sports should be alert to the presence of cold or numbing of body parts, particularly the nose, ears, and extremities, and they should review methods to produce local warming and know to seek shelter if they detect symptoms of local cold injury. Application of petrolatum (Vaseline) to the nose and ears gives certain protection against frostbite.

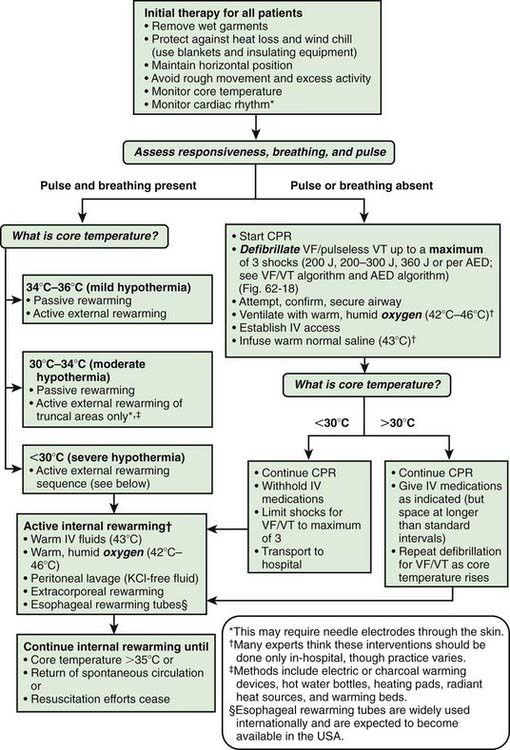

Treatment at the scene aims at prevention of further heat loss and early transport to adequate shelter. Dry clothing should be provided as soon as practical, and transport should be undertaken if the victim has a pulse. If no pulse is detected at the initial review, cardiopulmonary resuscitation is indicated (Chapter 62; Fig. 69-1). During transfer, jarring and sudden motion should be avoided because these occurrences may cause ventricular arrhythmia. It is often difficult to attain a normal sinus rhythm during hypothermia.

Figure 69-1 Hypothermia treatment algorithm for adult-size children and adolescents. AED, automated external defibrillator; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; IV, intravenous; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

(From Guidelines 2000 for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Part 8: advanced challenges in resuscitation: section 3: special challenges in ECC. The American Heart Association in collaboration with the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation, Circulation 102:1229–1252, 2000.)

If the patient is conscious, mild muscle activity should be encouraged, and a warm drink offered. If the patient is unconscious, external warming should be undertaken initially with use of blankets and a sleeping bag; wrapping the patient in blankets or sleeping bag with a warm companion may increase the efficiency of warming. On arrival at a treatment center, while a warming bath of 45-48°C (113-118°F) water is prepared, the patient should be warmed through inhalation of warm, moist air or oxygen or with heating pads or thermal blankets. Monitoring of serum chemistry values and an electrocardiogram are necessary until the core temperature rises to >35°C and can be stabilized. Control of fluid balance, pH, blood pressure, and oxygen concentration is necessary in the early phases of the warming period and resuscitation. In severe hypothermia, there may be a combined respiratory and metabolic acidosis. Hypothermia may falsely elevate pH; nonetheless, most authorities recommend warming the arterial blood gas specimen to 37°C before analysis and regarding the result as one from a normothermic patient. In patients with marked abnormalities, warming measures, such as gastric or colonic irrigation with warm saline or peritoneal dialysis, may be considered, but the effectiveness of these measures in treating hypothermia is unknown. In accidental deep hypothermia (core temperature 28°C) with circulatory arrest, rewarming with cardiopulmonary bypass may be lifesaving for previously healthy young individuals.

Chilblain (Pernio)

Chilblain (pernio) is a form of cold injury in which erythematous, vesicular, or ulcerative lesions occur. The lesions are presumed to be of vascular or vasoconstrictive origin. They are often itchy, may be painful, and result in swelling and scabbing. The lesions are most often found on the ears, the tips of the fingers and toes, and exposed areas of the legs. The lesions last for 1-2 wk but may persist for longer. Treatment consists of prophylaxis: avoiding prolonged chilling and protecting potentially susceptible areas with a cap, gloves, and stockings. Prazosin and phenoxybenzamine may be helpful in improving circulation if this is a recurrent problem. For significant itching, local corticosteroid preparations may be helpful.

Cold-Induced Fat Necrosis (Panniculitis)

A common, usually benign injury, cold-induced fat necrosis occurs upon exposure to cold air, snow, or ice and manifests in exposed (or, less often, covered) surfaces as red (or, less often, purple to blue) macular, papular, or nodular lesions. Treatment is with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. The lesions may last 10 days to 3 wk (Chapter 652) but may persist for longer. There is a possibility of severe coagulopathy associated with poor outcome in some of the severe cold injuries, thus meriting anticoagulation therapy.

Bruen KJ, Ballard JR, Morris SE, et al. Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy. Arch Surg. 2007;142:546-551.

Hallam MJ, Cubison T, Dheansa B, Imray C. Managing frostbite. BMJ. 2010;341:1151-1156.

Shephard RJ. Metabolic adaptations to exercise in the cold: an update. Sports Med. 1993;16:266-289.

Twomey JA, Peltier GL, Zera RT. An open-label study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of tissue plasminogen activator in treatment of severe frostbite. J Trauma. 2005;59:1350-1354.

Walpoth BH, Walpoth-Aslan BN, Mattle HP, et al. Outcome of survivors of accidental deep hypothermia and circulatory arrest treated with extracorporeal blood warming. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1500-1505.