Chapter 295 Cysticercosis

Etiology

Humans can be the definitive host (parasite sexual reproduction) as well as the intermediate host (parasite asexual reproduction) of Taenia solium, the pork tapeworm. Infection with the invasive intermediate stage (cysticercus) is called cysticercosis. Unlike Taenia saginata, the intermediate stage of T. solium is invasive with a tropism for the central nervous system (CNS) in humans, causing neurocysticercosis. The risk of cysticercosis may be the same for individuals who eat or do not eat pork, since humans acquire the intermediate form by ingestion of food or water contaminated with the eggs of T. solium. By contrast, consumption of infected undercooked pork produces intestinal infection with the adult worm (Chapter 294). Individuals harboring an adult worm may infect themselves with the eggs by the fecal-oral route. Reverse peristalsis in the small intestine has also been implicated as a means of autoinfection. In the small intestine, the egg releases an oncosphere that crosses the gut wall and spreads hematogenously to many tissues, primarily brain and muscle. Wherever the eggs lodge, they produce small (0.2-0.5 cm) fluid-filled bladders containing a single protoscolex, the juvenile-stage parasite.

Epidemiology

The pork tapeworm is distributed worldwide wherever pigs are raised. Intense transmission occurs in Central and South America, India, Indonesia, Korea, and China as well as some areas of Africa. In these areas, 20-50% of cases of epilepsy may be due to cysticercosis. Most cases of cysticercosis in the USA are imported; transmission is uncommon but occurs.

Pathogenesis

Living, intact cystic stages usually do not provoke a strong immunologic response. Intact cysts can be associated with disease when the initial parasite invasion of the brain is massive or when they obstruct the flow of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Most cysts remain viable for 5-10 yr and then begin to degenerate, followed by a vigorous host response. The natural history of cysts is to resolve by complete resorption or calcification.

Clinical Manifestations

Seizures are the presenting finding in ~70% of cases, although any cognitive or neurologic abnormality ranging from psychosis to stroke may be a manifestation of cysticercosis. It is useful to classify neurocysticercosis as parenchymal, intraventricular, meningeal, spinal, or ocular on the basis of anatomic location, clinical presentation, and radiologic appearance. Prognosis and management vary with location.

Parenchymal neurocysticercosis produces seizures as well as focal neurologic deficits. The seizures are generalized in 80% of cases but frequently begin as simple or complex partial seizures. Rarely, cerebral infarction can result from obstruction of small terminal arteries or vasculitis. With extensive frontal lobe disease, symptoms of intellectual deterioration with dementia or parkinsonism may obfuscate diagnosis until focal signs appear. A fulminant encephalitis-like presentation also occurs, most frequently in children who have had a massive initial infection. Intraventricular neurocysticercosis (5-10% of all cases) is associated with hydrocephalus and acute, subacute, or intermittent signs of increased intracranial pressure without localizing signs. The 4th ventricle is the most common site for obstruction and symptoms; cysts in the lateral ventricles are less likely to cause obstruction. Meningeal neurocysticercosis is associated with signs of meningeal irritation and also increased intracranial pressure that results from edema, inflammation, or the presence of a cyst obstructing flow of CSF. Chronic basilar meningitis is associated with many forms of neurocysticercosis, but predominantly meningeal presentations. Racemose neurocysticercosis is a meningeal form of disease in which large, lobulated cysts appear in the basal cisterns. Spinal neurocysticercosis presents with evidence of spinal cord compression, nerve root pain, transverse myelitis, or meningitis. Ocular neurocysticercosis causes decreased visual acuity due to cysticerci floating in the vitreous, retinal detachment, iridocyclitis, or orbital mass effect. Outside of the CNS, cysts can sometimes be palpated under the skin, and very heavy infections in skeletal or heart muscle can result in myositis or carditis.

Diagnosis

Neurocysticercosis should be suspected in a child with onset of any neurologic, cognitive, or personality disorder and who also has a history of residence in an endemic area or a care provider from an endemic area. Seizures, hydrocephalus, unilateral visual impairment, or symptoms of encephalitis are particularly suspicious. Proglottids (segments) or eggs are observed in feces from only 25% of cases of neurocysticercosis; therefore, imaging studies and serologic tests are necessary to confirm a clinical suspicion.

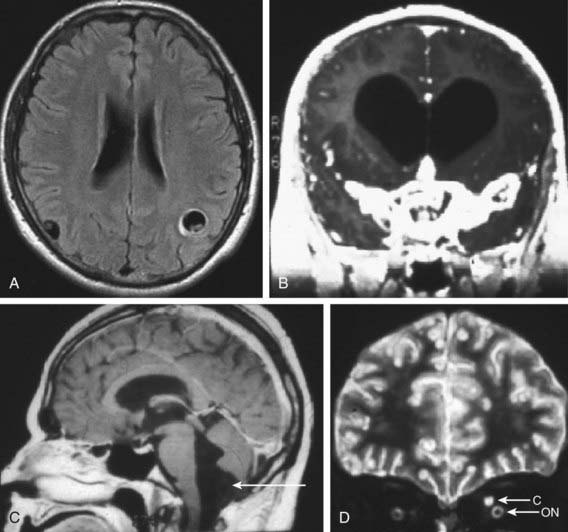

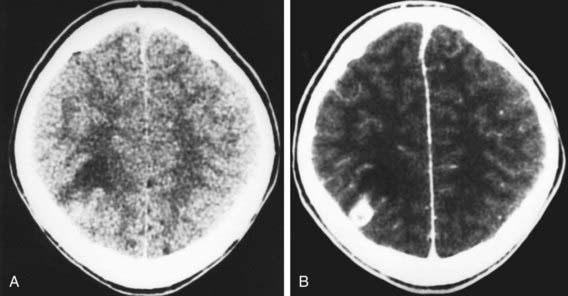

The most useful diagnostic study for parenchymal disease is MRI of the head. MRI provides the most information about cyst viability and associated inflammation. The protoscolex is sometimes visible within the cyst, which provides a pathognomonic sign for cysticercosis (Fig. 295-1A). The MRI also better detects basilar arachnoiditis (Fig. 295-1B), intraventricular cysts (Fig 295-1C), as well as those in the spinal cord. CT is best for identifying calcifications. A solitary parenchymal cyst, with or without contrast enhancement, and numerous calcifications are the most common findings in children (Fig. 295-2). Plain films may reveal calcifications in muscle or brain consistent with cysticercosis, but these are often nondiagnostic in children and may also be found in congenital toxoplasmosis.

Figure 295-1 A, MRI (T1 weighted) demonstrating 2 parenchymal cysts with protoscolices. B, MRI (T1 weighted) of cysticercal basilar arachnoiditis. C, MRI (T1 weighted) showing a cyst below the 4th ventricle (arrow). D, MRI (T2 weighted) showing a cysticercus (C) above the optic nerve (ON).

Figure 295-2 CT image of a solitary lesion of neurocysticercosis with (A) and without (B) contrast, showing contrast enhancement.

(Courtesy of Dr. Wendy G. Mitchell and Dr. Marvin D. Nelson, Children’s Hospital, Los Angeles.)

Serologic diagnosis using the enzyme-linked immunotransfer blot (EITB) is available commercially in the USA and through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Serum antibody testing has ~90% sensitivity and specificity; testing of CSF is not required. Persons with many parenchymal cysts almost always have a positive serum EITB test result. Cases with solitary lesions or old calcified disease may not have detectable antibodies. Neurocysticercosis is the most important and most frequent cause of eosinophilia in CSF, but this is not a consistent finding.

Differential Diagnosis

Neurocysticercosis can be confused clinically with encephalitis, stroke, meningitis, and many other conditions (Table 295-1). Clinical suspicion is based on travel history or a history of contact with an individual who might carry an adult tapeworm. On imaging studies, cysticerci can be difficult to distinguish from tuberculomas, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, toxoplasmosis, sarcoidosis, vasculitis, and tumor.

Table 295-1 DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF NEUROCYSTICERCOSIS ON NEUROIMAGING

SINGLE NON-ENHANCING CYSTIC LESION

Hydatid disease

Arachnoid cysts

Porencephaly

Cystic astrocytoma

Colloid cyst (third ventricle)

SEVERAL NON-ENHANCING CYSTIC LESIONS

Multiple metastases

Hydatid disease (rare)

ENHANCING LESIONS

Tuberculosis

Mycosis

Toxoplasmosis

Abscess

Early glioma

Metastasis

Arteriovenous malformation

CALCIFICATIONS

Tuberous sclerosis

Tuberculosis

Cytomegalovirus infection

Toxoplasmosis

From Garcia HH, Gonzalez AE, Evans CAW, et al: Taenia solium cysticercosis, Lancet 361:547–556, 2003.

Treatment

The initial objectives of the management of cysticerosis are to diagnosis and manage hydrocephalus due to ventricular obstruction. The next is to control seizure activity. Most associated seizures can be readily controlled using standard anticonvulsant regimens. If seizures are recurrent or associated with calcified lesions, treatment should be continued for 2-3 yr before attempting weaning from anticonvulsants. The inclusion of antiparasitic drugs is controversial, but evidence appears to increasingly point to benefit in certain cases. Causes other than cysticercosis, especially tuberculoma, must be excluded (see Table 295-1).

The natural history of parenchymal lesions is to resolve spontaneously with or without antiparasitic drugs. Most children present with solitary parenchymal cysts that resolve as readily with as without therapy. Other forms of the disease are less common in children. By contrast, multiple lesions and complex presentations are typical of disease in adults. One double-blind, placebo-controlled study demonstrated a significant decrease in generalized seizures for cysticercosis in adults treated with antiparasitic therapy. Subsequently, meta-analyses of 4-6 randomized, controlled trials suggested an overall 2-fold decrease in recurrence of generalized seizures in patients treated with albendazole compared to those not treated. The benefit to children was significantly less, perhaps since most of these infections were with only 1-2 cysts. There is little evidence that the management of acute symptoms improves with these drugs, and they are not indicated where there are only degenerating or calcified lesions.

Subarachnoid disease has a poor prognosis if untreated, but antiparasitic treatment is associated with a better outcome in comparison with historical controls. Ocular cysticercosis is essentially a surgical disease, although there are reports of cure using medical therapy alone. The outcome is not good in most cases, and enucleation is frequently required.

Albendazole is the antiparasitic drug of choice (15 mg/kg/day PO divided bid for 7 days; maximum 800 mg/day). It can be taken with a fatty meal to improve absorption. Praziquantel is an alternative (50-100 mg/kg/day PO divided tid for 28 days), but requires more complicated management due to an interaction with corticosteroids. A worsening of symptoms can follow the use of either drug due to the host’s inflammatory response to the dying parasite. Patients should be medicated with prednisolone 2 mg/kg/day or 0.15 mg/kg/day oral dexamethasone, either concurrent with albendazole, or starting albendazole on the third day of corticosteroids. Single antiepileptic agents are usually administered as well if there has been a history of seizures. If no anticysticercal drugs are administered, it is necessary to determine whether these patients carry adult worms, posing a public health risk and risk of continued autoinfection.

Prevention

All family members of index cases of cysticercosis as well as persons handling the food of index cases should be examined for signs of disease or evidence of adult worms. Attention to personal hygiene, proper handwashing by food handlers, and avoidance of fresh fruits and vegetables in areas endemic for T. solium help prevent ingestion of eggs. All pork should be cooked thoroughly. Veterinary vaccines for several cestode infections have a high degree of efficacy and have a potential role in decreasing parasite transmission.

Abba K, Ramaratnam S, Ranganathan IN: Anthelmintics for people with neurocysticercosis (review), Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3:CD000215, 2010.

Del Brutto OH, Roos KL, Coffey CS, et al. Meta-analysis: cysticidal drugs for neurocysticercosis: albendazole and praziquantel. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:43-51.

Mazumdar M, Pandharipande P, Poduri A. Does albendazole affect seizure remission and computed tomography response in children with neurocysticercosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Child Neurol. 2007;22:135-142.

Nash TE, Singh G, White AC, et al. Treatment of neurocysticercosis: current status and future research needs. Neurology. 2006;67:1120-1127.

Serpa JA, Graviss EA, Kass JS, et al. Neurocysticercosis in Houston, Texas. Medicine. 2011;90(1):81-86.

Serpa JA, Yancey LS, White ACJr. Review. Advances in the diagnosis and management of neurocysticercosis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2006;4:1051-1061.