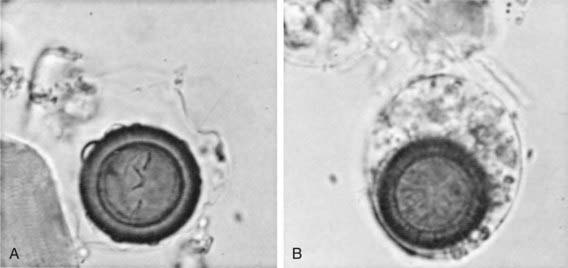

Chapter 294 Adult Tapeworm Infections

Cestodes are segmented flat worms popularly referred to as tapeworms. The family is large with a wide range of sizes (8 mm to 10 m) and morbidities. Their life cycle is usually distributed between 2 hosts, although some species, such as Taenia solium, can complete development in 1 host and others, such as Diphyllobothrium latum, require 3 hosts. A consistent theme in cestode developmental biology is that the adult, sexually replicating stages inhabit the gastrointestinal tract and have low pathogenicity, whereas, the asexually reproducing intermediate stages are tissue invasive and are potentially the cause of very serious morbidity. Depending on the species, humans can be host to either stage or both (Table 294-1). The most important invasive cestodes, T. solium (Chapter 295) and Echinococcus species (Chapter 296), are presented in subsequent chapters. The differential distribution of adult versus intermediate stages also influences diagnostic approaches. Infection with the adult worm can be easily diagnosed by finding eggs or segments of adult worms in the stool, whereas the invasive stage of the parasite cannot be observed in any easily sampled fluid. Infection with an intermediate stage, therefore, must be diagnosed by serologic tests, imaging, or invasive procedures.

Taeniasis (Taenia Saginata and Taenia Solium)

Etiology

The adult beef tapeworm (Taenia saginata) and the pork tapeworm (Taenia solium) are large parasites (4-10 m) named for their intermediate hosts and are found only in the human intestine. Like the adult stage of all tapeworms, their body is a series of hundreds or thousands of flattened segments (proglottids) whose most anterior segment (scolex) anchors the parasite to the bowel wall. New segments arise from the tail of the scolex followed by progressively more mature ones. The gravid terminal segments contain 50,000-100,000 eggs, and the eggs or the intact proglottids themselves pass out of the body in the stool. These 2 tapeworms differ most significantly in that the intermediate stage of the pork tapeworm (cysticercus) can also infect humans and cause significant morbidity (Chapter 295). A 3rd species found in Asia (Taenia asiatica) cannot be distinguished from the beef tapeworm, but its intermediate stage infects the liver of pigs and may produce invasive disease in humans.

Epidemiology

The pork and beef tapeworms are distributed worldwide, with the highest risk for infection in Central America, Africa, India, Southeast Asia, and China. The prevalence in adults may not reflect the prevalence in young children, because cultural practices may dictate how well meat is cooked and how much is served to children.

Pathogenesis

Uncomplicated infection with the adult beef or pork tapeworm by itself is an infrequent source of symptoms. When children ingest raw or undercooked infected meat, gastric acid and bile facilitate release of the immature scolex that attaches to the lumen of the small intestine. The parasite adds new segments, and after 2-3 mo the terminal segments mature, become gravid, and appear in stool.

Clinical Manifestations

Adult beef and pork tapeworms cause very little overt morbidity apart from nonspecific abdominal symptoms. The proglottids of these tapeworms can be noticeable in stool or underwear. They are also motile and sometimes produce anal pruritus. The adult beef and pork tapeworms are rare causes of intestinal obstruction, pancreatitis, cholangitis, and appendicitis.

Diagnosis

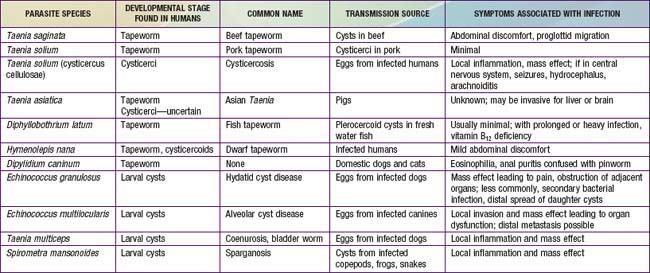

It is important to identify the infecting species of tapeworm. Carriers of adult pork tapeworms are at increased risk for transmitting eggs with the pathogenic intermediate stage (cysticercus) to themselves or others, whereas children infected with the beef tapeworm are a risk only to livestock. Because proglottids are generally passed intact, visual examination for gravid proglottids in the stool is a sensitive test; these segments may be used to identify species. Eggs, by contrast, are often absent from stool and cannot reliably distinguish between T. saginata and T. solium (Fig. 294-1). If the parasite is completely expelled, the scolex of each species is diagnostic. The scolex of T. saginata has only a set of 4 anteriorly oriented suckers, whereas T. solium is armed with a double row of hooks in addition to suckers. The proglottids of T. saginata have more than 20 branches from a central uterine structure, and those of T. solium have 10 or fewer. When in doubt, more proglottids should be obtained or the sample should be referred to a laboratory with parasitologic expertise. Only molecular methods can be used to distinguish T. saginata from T. asiatica.

Figure 294-1 A and B, Eggs of Taenia saginata recovered from feces (original magnification ×400). The eggs are generally bile stained, dark, and prismatic. There is occasionally some surrounding cellular material from the proglottid in which the egg develops, which is more evident in B than in A. The larva within the egg shows 3 pairs of hooklets (A), which may occasionally be observed in motion.

Differential Diagnosis

Anal pruritus may mimic symptoms of pinworm (Enterobius vermicularis) infection. D. latum or even Ascaris lumbricoides may be mistaken for T. saginata or T. solium in stools.

Treatment

Infections with all adult tapeworms respond to praziquantel (25 mg/kg PO once). An alternative treatment for taeniasis is niclosamide (50 mg/kg PO once for children, 2 g PO once for adults). However, this medication is no longer available in the USA. The parasite is usually expelled on the day of administration.

Diphyllobothriasis (Diphyllobothrium Latum)

Etiology

The fish tapeworm, Diphyllobothrium latum, is the longest human tapeworm (>10 m) and has an organization similar to that of other adult cestodes. An elongated scolex equipped with slits (bothria) along each side but no suckers or hooks is followed by thousands of segments looped in the small bowel. The terminal gravid proglottid detaches periodically but tends to disintegrate before expulsion, thus releasing its eggs into the feces. In contrast to taeniids, the life cycle of D. latum requires 2 intermediate hosts. Small fresh water crustaceans (copepods) take up the larvae that hatch from parasite eggs. The parasite passes up the food chain as small fish eat the copepods and are in turn eaten by larger fish. In this way, the juvenile parasite becomes concentrated in pike, walleye, perch, burbot, and perhaps salmon associated with aquaculture of this species. Consumption of raw or undercooked fish leads to human infection with adult fish tapeworms.

Epidemiology

The fish tapeworm is most prevalent in the temperate climates of Europe, North America, and Asia but may be found in cold lakes at high altitudes in South America and Africa. In North America, the prevalence is highest in Alaska, Canada, and the northern USA. The tapeworm is found in fish from those areas brought to market in the continental USA. Persons who prepare raw fish for home or commercial use or who sample fish before cooking are particularly at risk for infection.

Pathogenesis

The adult worm efficiently scavenges vitamin B12 for its own use in the constant production of large numbers of segments and as many as 1 million eggs per day. As a result, diphyllobothriasis causes megaloblastic anemia in 2-9% of infections. Children with other causes of vitamin B12 or folate deficiency such as chronic infectious diarrhea, celiac disease, or congenital malabsorption are more likely to develop symptomatic infection.

Clinical Manifestations

Infection is largely asymptomatic, except in those who develop B12 or folate deficiency. Megaloblastic anemia with leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, glossitis, and signs of spinal cord posterior column degeneration (loss of vibratory sense, proprioception, and coordination) can be evidence of advanced nutritional deficiency due to diphyllobothriasis. It should be mentioned that an invasive form of infection termed sparganosis results when the intermediate form of this or other members of this group of tapeworm are introduced subcutaneously. Skin, muscle, eye, and brain have been sites of invasion.

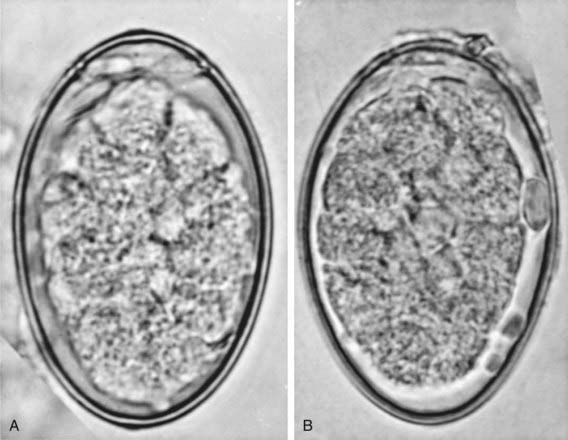

Diagnosis

Parasitologic examination of the stool is useful because eggs are abundant in the feces and have morphology distinct from that of all other tapeworms. The eggs are ovoid and have an operculum, which is a cap structure at one end that opens to release the embryo (Fig. 294-2). The worm itself has a distinct scolex and proglottid morphology; however, these are not likely to be passed spontaneously.

Differential Diagnosis

A segment or a whole section of the worm might be confused with Taenia or Ascaris after it is passed. Pernicious anemia, bone marrow toxins, and dietary restrictions may contribute to or mimic diphyllobothriasis.

Hymenolepiasis (Hymenolepis)

Infection with Hymenolepis nana, the dwarf tapeworm, is very common in developing countries. It is a major cause of eosinophilia, and although it rarely causes overt disease, the presence of H. nana eggs in stool may serve as a marker for exposure to poor hygienic conditions. The intermediate stage develops in various hosts (e.g., rodents, ticks, and fleas), and the entire life cycle can be completed in humans. Therefore, hyperinfection with thousands of small adult worms in a single child may occur. A similar infection may occur less commonly with the species Hymenolepis diminuta. Eggs but not segments may be found in the stool. H. nana infection responds to praziquantel (25 mg/kg PO once).

Dipylidiasis (Dipylidium Caninum)

Dipylidium caninum is a common tapeworm of domestic dogs and cats, yet human infection is relatively rare. Direct transmission between pets and humans does not occur; human infection requires ingestion of the parasite’s intermediate host, the dog or cat flea. Infants and small children are particularly susceptible because of their level of hygiene, generally more intimate contact with pets, and activities in areas where fleas can be encountered. Anal pruritus, vague abdominal pain, and diarrhea have at times been associated with dipylidiasis, which is thus sometimes confused with pinworm (E. vermicularis). Dipylidiasis responds to treatment with praziquantel (5-10 mg/kg PO once). Deworming pets and flea control are the best preventive measures.

Anantaphruti MT, Yamasaki H, Nakao M, et al. Sympatric occurrence of Taenia solium, T. saginata, and T. asiatica, Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1413-1416.

Craig P, Ito A. Intestinal cestodes. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:524-532.

Samkari A, Kiska DL, Riddell SW, et al. Dipylidium caninum mimicking recurrent Enterobius vermicularis (pinworm) infection. Clin Pediatr. 2008;47:397-399.

Scholz T, Garcia HH, Kuchta R, et al. Update on the human broad tapeworm (genus Diphyllobothrium), including clinical relevance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:146-160.