Chapter 321 Pyloric Stenosis and Other Congenital Anomalies of the Stomach

321.1 Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis

Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis occurs in 1-3/1,000 infants in the United States. It is more common in whites of northern European ancestry, less common in blacks, and rare in Asians. Males (especially first-borns) are affected approximately 4 to 6 times as often as females. The offspring of a mother and, to a lesser extent, the father who had pyloric stenosis are at higher risk for pyloric stenosis. Pyloric stenosis develops in approximately 20% of the male and 10% of the female descendants of a mother who had pyloric stenosis. The incidence of pyloric stenosis is increased in infants with B and O blood groups. Pyloric stenosis is occasionally associated with other congenital defects, including tracheoesophageal fistula and hypoplasia or agenesis of the inferior labial frenulum.

Etiology

The cause of pyloric stenosis is unknown, but many factors have been implicated. Pyloric stenosis is usually not present at birth and is more concordant in monozygotic than dizygotic twins. It is unusual in stillbirths and probably develops after birth. Pyloric stenosis has been associated with eosinophilic gastroenteritis, Apert syndrome, Zellweger syndrome, trisomy 18, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, and Cornelia de Lange syndrome. An association has been found with the use of erythromycin in neonates with highest risk if the medication is given within the 1st 2 wk of life. There have also been reports of higher incidence of pyloric stenosis among mostly female infants of mothers treated with macrolide antibiotics during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Abnormal muscle innervation, elevated serum levels of prostaglandins, and infant hypergastrinemia has been implicated. Reduced levels of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) have been found with altered expression of the nNOS exon 1c regulatory region, which influences the expression of the nNOS gene. Reduced nitric oxide might contribute to the pathogenesis of pyloric stenosis.

Clinical Manifestations

Nonbilious vomiting is the initial symptom of pyloric stenosis. The vomiting may or may not be projectile initially but is usually progressive, occurring immediately after a feeding. Emesis might follow each feeding, or it may be intermittent. The vomiting usually starts after 3 wk of age, but symptoms can develop as early as the 1st wk of life and as late as the 5th mo. About 20% have intermittent emesis from birth that then progresses to the classic picture. After vomiting, the infant is hungry and wants to feed again. As vomiting continues, a progressive loss of fluid, hydrogen ion, and chloride leads to hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis. Greater awareness of pyloric stenosis has led to earlier identification of patients with fewer instances of chronic malnutrition and severe dehydration and at times a subclinical self-resolving hypertrophy.

Hyperbilirubinemia is the most common clinical association of pyloric stenosis, also known as icteropyloric syndrome. Unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia is more common than conjugated and usually resolves with surgical correction. It may be associated with a decreased level of glucuronyl transferase as seen in ∼5% of affected infants; mutations in the bilirubin uridine diphosphate glucuronosyl transferase gene (UGT1A1) have also been implicated. If conjugated hyperbilirubinemia is a part of the presentation, other etiologies need to be investigated. Other coexistent clinical diagnoses have been described, including eosinophilic gastroenteritis, hiatal hernia, peptic ulcer, congenital nephrotic syndrome, congenital heart disease, and congenital hypothyroidism.

The diagnosis has traditionally been established by palpating the pyloric mass. The mass is firm, movable, ∼2 cm in length, olive shaped, hard, best palpated from the left side, and located above and to the right of the umbilicus in the mid-epigastrium beneath the liver’s edge. The olive is easiest palpated after an episode of vomiting. After feeding, there may be a visible gastric peristaltic wave that progresses across the abdomen (Fig. 321-1).

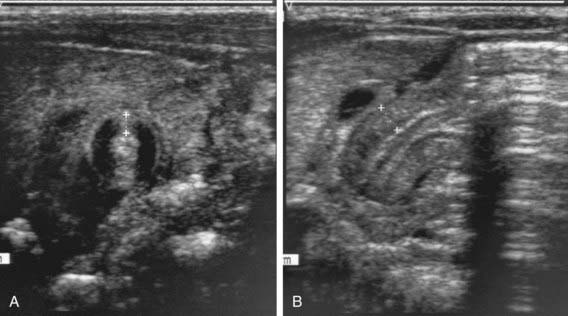

Two imaging studies are commonly used to establish the diagnosis. Ultrasound examination confirms the diagnosis in the majority of cases. Criteria for diagnosis include pyloric thickness 3-4 mm, an overall pyloric length 15-19 mm, and pyloric diameter of 10-14 mm (Fig. 321-2). Ultrasonography has a sensitivity of ∼95%. When contrast studies are performed, they demonstrate an elongated pyloric channel (string sign), a bulge of the pyloric muscle into the antrum (shoulder sign), and parallel streaks of barium seen in the narrowed channel, producing a “double tract sign” (Fig. 321-3).

Differential Diagnosis

Gastric waves are occasionally visible in small, emaciated infants who do not have pyloric stenosis. Infrequently, gastroesophageal reflux, with or without a hiatal hernia, may be confused with pyloric stenosis. Gastroesophageal reflux disease can be differentiated from pyloric stenosis by radiographic studies. Adrenal insufficiency from the adrenogenital syndrome can simulate pyloric stenosis, but the absence of a metabolic acidosis and elevated serum potassium and urinary sodium concentrations of adrenal insufficiency aid in differentiation (Chapter 570). Inborn errors of metabolism can produce recurrent emesis with alkalosis (urea cycle) or acidosis (organic acidemia) and lethargy, coma, or seizures. Vomiting with diarrhea suggests gastroenteritis, but patients with pyloric stenosis occasionally have diarrhea. Rarely, a pyloric membrane or pyloric duplication results in projectile vomiting, visible peristalsis, and, in the case of a duplication, a palpable mass. Duodenal stenosis proximal to the ampulla of Vater results in the clinical features of pyloric stenosis but can be differentiated by the presence of a pyloric mass on physical examination or ultrasonography.

Treatment

The preoperative treatment is directed toward correcting the fluid, acid-base, and electrolyte losses. Correction of the alkalosis is essential to prevent postoperative apnea, which may be associated with anesthesia. Most infants can be successfully rehydrated within 24 hr. Vomiting usually stops when the stomach is empty, and only an occasional infant requires nasogastric suction.

The surgical procedure of choice is pyloromyotomy. The traditional Ramstedt procedure is performed through a short transverse skin incision. The underlying pyloric mass is cut longitudinally to the layer of the submucosa, and the incision is closed. Laparoscopic technique is equally successful and in one study resulted in a shorter time to full feedings and discharge from the hospital as well as greater parental satisfaction. The success of laparoscopy depends on the skill of the surgeon. Postoperative vomiting occurs in half the infants and is thought to be secondary to edema of the pylorus at the incision site. In most infants, however, feedings can be initiated within 12-24 hr after surgery and advanced to maintenance oral feedings within 36-48 hr after surgery. Persistent vomiting suggests an incomplete pyloromyotomy, gastritis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or another cause of the obstruction. The surgical treatment of pyloric stenosis is curative, with an operative mortality of 0-0.5%. Endoscopic balloon dilatation has been successful in infants with persistent vomiting secondary to incomplete pyloromyotomy.

Conservative management with nasodudodenal feedings is advisable in patients who are not good surgical candidates. Oral and intravenous atropine sulfate (pyloric muscle relaxant) has also been described when surgical treatment is not available.

Chung E. Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: genes and environment. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:1003.

Kawahara H, Takama Y, Yoshida H, et al. Medical treatment of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: should we always slice the “olive”? J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1848.

Singh UK, Kumar R, Prasad R. Oral atropine sulfate for infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Indian Pediatr. 2005;42:473.

Sorensen HT, Skriver MV, Pedersen L, et al. Risk of infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis after maternal postnatal use of macrolides. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:104.

To T, Wajja A, Wales PW, Langer JC. Population demographic indicators associated with incidence of pyloric stenosis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:520.

Yagmurlu A. Laparoscopic versus open pyloromyotomy. Lancet. 2009;373:358-360.

321.2 Congenital Gastric Outlet Obstruction

Gastric outlet obstruction resulting from pyloric atresia and antral webs is uncommon and accounts for <1% of all the atresias and diaphragms of the alimentary tract. The cause of the defects is unknown. Pyloric atresia has been associated with epidermolysis bullosa and usually presents in early infancy. The gender distribution is equal.

Clinical Manifestations

Infants with pyloric atresia present with nonbilious vomiting, feeding difficulties, and abdominal distention during the 1st day of life. Polyhydramnios occurs in the majority of cases, and low birthweight is common. The gastric aspirate at birth is large (>20 mL fluid) and should be removed to prevent aspiration. Rupture of the stomach may occur as early as the 1st 12 hr of life. Infants with antral web may present with less dramatic symptoms, depending on the degree of obstruction. Older children with antral webs present with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and weight loss.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of congenital gastric outlet obstruction is suggested by the finding of a large, dilated stomach on abdominal plain radiographs or in utero ultrasonography. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) contrast series is usually diagnostic and demonstrates a pyloric dimple. When contrast studies are performed, care must be taken to avoid possible aspiration. An antral web may appear as a thin septum near the pyloric channel. In older children, endoscopy has been helpful in identifying antral webs.

321.3 Gastric Duplication

Gastric duplications are uncommon cystic or tubular structures that usually occur within the wall of the stomach. They account for 2-7% of all GI duplications. They are most commonly located on the greater curvature. Most are <12 cm in diameter and do not usually communicate with the stomach lumen; however, they do have common blood supply. Associated anomalies occur in as many as 35% of patients. Several hypotheses for the etiology of the duplication cysts have been developed including the splitting notochord theory, diverticulization, canalization defects, and caudal twinning.

The most common clinical manifestations are associated with partial or complete gastric outlet obstruction. In 33% of patients, the cyst may be palpable. Communicating duplications can cause gastric ulceration and be associated with hematemesis or melena.

Radiographic studies usually show a paragastric mass displacing stomach. Ultrasound can show the inner hyperechoic mucosal and outer hypoechoic muscle layers that are typical of GI duplications. Surgical excision is the treatment for symptomatic gastric duplications.

321.4 Gastric Volvulus

The stomach is tethered longitudinally by the gastrohepatic, gastrosplenic, and gastrocolic ligaments. In the transverse axis, it is tethered by the gastrophrenic ligament and the retroperitoneal attachment of the duodenum. A volvulus occurs when 1 of these attachments is absent or elongated, allowing the stomach to rotate around itself. In some children, other associated defects are present, including intestinal malrotation, diaphragmatic defects, hiatal hernia, or adjacent organ abnormalities such as asplenia. Volvulus can occur along the longitudinal axis, producing organoaxial volvulus, or along the transverse axis, producing mesenteroaxial volvulus. Combined volvulus occurs if the stomach rotates around both organoaxial and mesenteroaxial axes.

The clinical presentation of gastric volvulus is nonspecific and suggests high intestinal obstruction. Gastric volvulus in infancy is usually associated with nonbilious vomiting and epigastric distention. It has also been associated with episodes of dyspnea and apnea in this age group. Acute volvulus can advance rapidly to strangulation and perforation. Chronic gastric volvulus is more common in older children; the children present with a history of emesis, abdominal pain and distention, early satiety, and failure to thrive.

The diagnosis is suggested in plain abdominal radiographs by the presence of a dilated stomach. Erect abdominal films demonstrate a double fluid level with a characteristic “beak” near the lower esophageal junction in mesenteroaxial volvulus. The stomach tends to lie in a vertical plane. In organoaxial volvulus, a single air-fluid level is seen without the characteristic beak with stomach lying in a horizontal plane. Upper GI series has also been used to aid the diagnosis.

Treatment of acute gastric volvulus is emergent surgery once a patient is stabilized. Laparoscopic gastropexy is the most common surgical approach. In selected cases of chronic volvulus in older patients, endoscopic correction has been successful.

321.5 Hypertrophic Gastropathy

Hypertrophic gastropathy in children is uncommon and, in contrast to that in adults (Ménétrier disease), is usually a transient, benign, and self-limited condition.

Pathogenesis

The condition is most often secondary to cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, but other agents, including herpes simplex virus, Giardia, and Helicobacter pylori have also been implicated. The pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying the clinical picture are not completely understood but might involve widening of gap junctions between gastric epithelial cells with resultant fluid and protein losses. There is an association with increased expression of transforming growth factor (TGF)-α in gastric mucosal tissue shown in CMV induced gastropathy. H. pylori infection can cause the elevation of serum glucagon-like peptide-2 levels, a mucosal growth-inducing gut hormone.

Clinical Manifestations

Clinical manifestations include vomiting, anorexia, upper abdominal pain, diarrhea, edema (hypoproteinemic protein-losing enteropathy), ascites, and, rarely, hematemesis if ulceration occurs.

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis

The mean age at diagnosis is 5 yr (range, 2 days-17 yr); the illness usually lasts 2-14 wk, with complete resolution being the rule. Endoscopy with biopsy and tissue CMV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is diagnostic. The upper GI series might show thickened gastric folds. The differential diagnosis includes eosinophilic gastroenteritis, gastric lymphoma or carcinoma, Crohn disease, and inflammatory pseudotumor.

Treatment

Therapy is supportive and should include adequate hydration, H2 receptor blockade, and albumin replacement if the hypoalbuminemia is symptomatic. When H. pylori are detected, appropriate treatment is recommended. Ganciclovir in CMV-positive gastropathy is indicated only in severe cases. Complete recovery is the rule. This is not a chronic condition in children. Disease tends to have much more severe course in adult patients.

Graham-Maar RC, Russo P, Johnson AM, et al. A 2-year-old boy with emesis and facial edema. Med Gen Med. 2006;8:75.

Hoffer V, Finkelstein Y, Balter J, et al. Ganciclovir treatment in Ménétrier’s disease. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92:983-985.

Megged O, Schlesinger Y. Cytomegalovirus-associated protein-losing gastropathy in childhood. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:1217-1220.

Tokuhara D, Okano Y, Asou K, et al. Cytomegalovirus and Helicobacter pylori co-infection in a child with Ménétrier disease. Eur J Ped. 2007;166:63-65.

Watanabe K, Beinborn M, Nagamatsu S, et al. Menetrier’s disease in a patient with Helicobacter pylori infection is linked to elevated glucagon-like peptide-2 activity. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:477-481.