Chapter 547 Neoplasms and Adolescent Screening for Human Papilloma Virus

Gynecologic Malignancies

Cancer is the second most common cause of death in adolescents, after injuries. Although gynecologic malignancies are rare, they can be especially tragic given the emotional and psychologic impact associated with their diagnosis. Infertility, depression, and poor self-image may be lifelong issues for these patients.

The most common type of gynecologic malignancy found in children and adolescents is of ovarian origin and usually manifests as an abdominal mass, which must be distinguished from other organ-based tumors and ovarian functional, physiologic, inflammatory/infectious, or pregnancy-related processes. Ovarian neoplasms constitute 1% of all childhood malignancies, but account for 60-70% of all gynecologic malignancies in this age group. About 10-30% of all childhood or adolescent ovarian neoplasms are malignant. Less often, the vagina or cervix is a site of malignant lesions in children, with a few specific tumors having their greatest incidence within this population. Cervical dysplasia can occur in adolescents, and health care providers need to be aware of current screening guidelines as well as updates on preventive measures. Vulvar malignancies in children and adolescents are exceedingly rare.

Impact of Cancer Therapy on Fertility

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy are associated with acute ovarian failure and premature menopause. Risk factors include older age, abdominal or spinal radiation, and certain chemotherapeutic drugs, such as alkylating agents (cyclophosphamide, busulfan). Uterine irradiation is associated with infertility, spontaneous pregnancy loss, and intrauterine growth restriction. Decreased uterine volume has been noted in girls who received abdominal radiation. The vagina, bladder, ureters, urethra, and rectum can also be injured by radiation. Vaginal shortening, vaginal stenosis, urinary tract fistulas, and diarrhea are important side effects of pelvic irradiation for pelvic cancers. Pregnancy outcomes appear to be influenced by prior chemotherapy and radiation treatment; 15% of childhood cancer survivors have infertility. Cancer survivors have an increased rate of spontaneous abortions, premature deliveries, and low-birthweight infants compared to their normal healthy siblings. No data support an increased incidence of congenital malformations in offspring.

Childhood cancer survivors require extensive counseling about these specific future health implications. As part of informed consent for cancer therapy, the possibility of infertility should be discussed with young patients and their families. Options for fertility preservation (pretreatment with GnRH analogs, harvesting and cryopreservation of oocytes and ovarian tissue) are at present experimental. Premature ovarian insufficiency is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular complications, osteoporosis, and difficulties with sexual function. Risks and benefits of hormonal therapy need to be addressed.

Ovaries

Neonatal and Pediatric Ovarian Cysts

Normal follicles or physiologic ovarian cysts are seen by ultrasound examination of the ovaries in all healthy prepubertal girls. Most of these are <1 cm in diameter and not pathologic. In the neonatal period, physiologic follicular cysts due to maternal estrogen stimulation usually resolve spontaneously and may be followed with serial ultrasounds in the asymptomatic child. Children with an ovarian mass might have no symptoms and the mass may be detected incidentally or during a routine examination. Other children present with abdominal pain that may be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, or urinary frequency or retention. The cyst’s most common complication, ovarian torsion, can result in loss of the ovary (autoamputation of the ovary has been documented to occur antenatally). Successful reports of antenatal aspiration and postnatal laparoscopic treatment exist. Large cysts (>4-5 cm), those with complex characteristics, or any ovarian cyst in premenarchal girls with associated signs or symptoms of hormonal stimulation deserve prompt evaluation. The incidence of ovarian cysts increases again with puberty.

Functional Cysts

Hemorrhagic cysts are an expected part of follicular development during the menstrual cycle. Normally, a dominant follicle forms and increases in size. Following ovulation, the dominant follicle becomes a corpus luteum that, if it bleeds, is termed a hemorrhagic corpus luteum. These can become symptomatic owing to size or peritoneal irritation from blood, and they have a characteristic complex appearance on ultrasound. Expectant management for a presumed functional or hemorrhagic cyst is appropriate. Physiologic cysts are usually no larger than 5 cm and resolve over the course of 6-8 wk during subsequent ultrasound imaging. Monophasic oral contraceptives can be used to suppress follicular development to prevent formation of additional cysts.

Teratomas

The most common neoplasm in adolescents is the mature cystic teratoma (dermoid cyst). Most are benign and contain mature tissue of ectodermal (skin, hair, sebaceous glands), mesodermal, or endodermal origin. Occasionally well-formed teeth, cartilage, and bone are found. Calcification on an abdominal radiograph is often a hallmark of a benign teratoma. These tumors may be asymptomatic and found incidentally, or they can manifest as a mass or with abdominal pain (associated with torsion or rupture). If the major component of the dermoid is thyroid tissue (struma ovarii), hyperthyroidism can be the clinical presentation. Benign teratomas should be carefully resected, preserving as much normal ovarian tissue as possible. Oophorectomy (and salpingoophorectomy) for this benign lesion is excessive treatment. During surgery, both ovaries should be evaluated, and if there is any question about the nature of the lesion, the specimen should be evaluated by a pathologist. An association of dermoid tumors with neural elements and anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis has been reported. Excision of the ovarian tumor has led to improvement in neurologic symptoms in some patients.

Immature teratoma of the ovary is an uncommon tumor, accounting for less than 1% of ovarian teratomas. In contrast to the mature cystic teratoma, which is encountered most often during the reproductive years but occurs at all ages, the immature teratoma has a specific age incidence, occurring most commonly in the first 2 decades of life. By definition, an immature teratoma contains immature neural elements. Because the lesion is rarely bilateral in its ovarian involvement, the present method of therapy consists of unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with wide sampling of peritoneal implants.

Cystadenomas

Serous and mucinous cystadenomas are the second most common benign ovarian tumor. These cystic lesions can become very large, yet with care, the tumor can be resected, preserving normal ovarian tissue for future reproductive potential.

Endometriomas

Endometriosis is a syndrome defined by the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue usually located within the pelvis and abdomen. The principal clinical symptoms in adolescents consist of severe menstrual pain and pelvic pain. Endometriomas (chocolate cysts) form when the ovaries are involved and are collections of old blood and hemosiderin within an endometrium-lined cyst. They have a typical homogeneous echogenic appearance on ultrasound, and are more common in adults than in adolescents. Conservative management (suppressive therapy with ovulation suppression, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]) and ovarian cystectomy with preservation of as much functioning ovary as possible is recommended for adolescents.

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Tubo-ovarian Abscess

Pelvic inflammatory disease complicated by a tubo-ovarian abscess should be considered in a sexually active adolescent with an adnexal mass and pain on examination (Chapter 114). These patients also typically exhibit fever with leukocytosis and cervical motion tenderness. Treatment consists of administration of intravenous antibiotics. If the lesion persists or is refractory to antibiotics, drainage of the pelvic abscess by interventional radiology should be considered.

Adnexal Torsion

Adnexal torsion of the ovary and/or fallopian tube can occur in children or adolescents with normal adnexa or those enlarged by cystic changes or ovarian neoplasms. When torsion occurs, the venous outflow is obstructed first, and the ovary swells and becomes hemorrhagic. Once the arterial flow is interrupted, necrosis begins. It is not known how long torsed adnexa will remain viable. When a female patient presents with lower abdominal pain, either episodic or constant, and if imaging studies shows unilateral enlargement of an adnexa, the diagnosis of adnexal torsion must be considered and acted upon. The sonographic presence of Doppler flow does not exclude the diagnosis of torsion. Prompt surgical intervention (by laparoscopy) is warranted if clinical suspicion is high. Detorsion of the adnexa and observation for viability is recommended, with excision only for obviously nonviable necrotic tissues. Oophoropexy (plication) of the affected and the contralateral adnexa remain controversial. Recovery of ovarian function after detorsion has been reported with identification of normal follicle development.

Ovarian Carcinoma

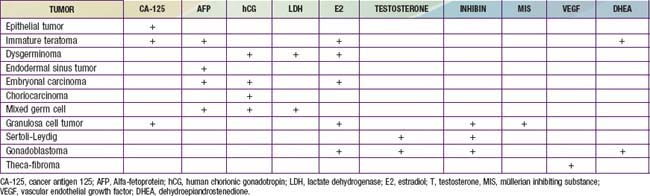

Ovarian cancer is very uncommon in children; only 2% of all ovarian cancers are diagnosed in patients <25 yr old. The SEER incidence rates are ≤0.8/100,000 at age 0-14 yr and 1.5/100,000 at ages 15-19 yr. Germ cell tumors are the most common and originate from primordial germ cells that then develop into a number of heterogeneous tumor types including dysgerminomas, malignant teratomas, endodermal sinus tumors, embryonal carcinomas, mixed cell neoplasms, and gonadoblastomas. Immature teratomas and endodermal sinus tumors are more aggressive malignancies than dysgerminomas and occur in a significantly higher proportion of younger girls (<10 yr of age). Sex-cord stromal tumors are more common among adolescents (Table 547-1). Tumor markers such as α-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and the antigen CA 125 are also used for diagnosis and treatment surveillance (Table 547-2).

Table 547-1 MALIGNANT OVARIAN TUMORS IN ADOLESCENTS

| TUMOR | OVERALL 5-YR SURVIVAL | CLINICAL FEATURES |

|---|---|---|

| GERM CELL TUMORS | ||

| Dysgerminoma | 85% | |

| Immature teratoma | 97-100% | All 3 germ layers present |

| Endodermal sinus tumor | 80% | |

| Choriocarcinoma | 30% | |

| Embryonal carcinoma | 25% | |

| Gonadoblastoma | 100% | |

| SEX CORD STROMAL TUMORS | ||

| Juvenile granulosa stroma cell tumor | 92% | |

| Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor | 70-90% | |

| Lipoid cell tumors | Heterologenous group with lipid-filled parenchyma | |

| Gynandroblastoma | Low-grade mixed tumors that produce either estrogen or androgen | |

Treatment is surgical excision followed by postoperative chemotherapy that usually consists of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP). Radiotherapy is sometimes administered for disease recurrence in dysgerminomas, but it is otherwise not included in routine treatment. Staging at the beginning of therapy is of the utmost importance. In rare cases, a second-look laparotomy may be indicated for neoplasms with teratomatous elements or for those incompletely resected.

Epithelial ovarian cancers account for 19% of ovarian masses in the pediatric population, with a total of 16% being malignant. These tumors manifest almost exclusively after puberty. Common presenting symptoms include dysmenorrhea, abdominal pain, abdominal distention, nausea and vomiting, and vaginal discharge. Tumors of low malignant potential are common in adolescents and account for 30% of epithelial ovarian cancers in this age group. Given the young age of this population, although not the standard of care for adult patients, consideration may be given to conserving the contralateral ovary and uterus if they appear normal. Data suggest that in patients with early-stage disease, such an approach with appropriate surgical staging results in optimal outcomes. Overall 5-yr survival rates are approximately 73%. The number of term pregnancies and use of oral contraceptives decrease the risk of invasive epithelial ovarian cancer. Young women with a family history of ovarian cancer should seriously consider using long-term oral contraceptives for the preventive benefits when pregnancy is not being sought.

Uterus

Rhabdomyosarcomas are the most common type of soft tissue sarcoma occurring in patients <20 yr of age (Chapter 494). They can develop in any organ or tissue within the body except bone, and roughly 3% originate from the uterus or vagina. Of the various histologic subtypes, embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas in the female patient most often occur in the genital tract of infants or young children. They are rapidly growing entities that can cause the tumor to be expelled through the cervix, with subsequent complications such as uterine inversion or large cervical polyps. Irregular vaginal bleeding may be another presenting clinical symptom. They are defined histologically by the presence of mesenchymal cells of skeletal muscle in various stages of differentiation intermixed with myxoid stroma. Treatment recommendations are based on protocols coordinated by the Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Study Group and consist of a multimodal approach including surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. Vincrinstine, adriamycin, and cyclophosphamide with or without radiation therapy are the first line of treatment. Attitudes toward surgical management have changed dramatically, with resection rates decreasing from 100% in 1972 to 13% in 1996. Chemotherapy with restrictive surgery has enabled many patients to retain their uterus while achieving excellent long-term survival rates.

Leiomyosarcomas and leiomyomas are extremely rare, occurring in <2/10 million individuals within the pediatric/adolescent age group. However, at least 13 cases in approximately 6,200 pediatric patients with AIDS have been reported. They usually involve the spleen, lung, or gastrointestinal tract, but they could also originate from uterine smooth muscle. Pathogenesis is thought to correlate with the Epstein-Barr virus (Chapter 246). Despite treatment that demands complete surgical resection (and chemotherapy for the sarcomas), they tend to recur frequently.

Endometrial stromal sarcoma and endometrial adenocarcinoma of the uterine corpus are extremely rare in children and adolescents, with only case reports noted in the literature. Vaginal bleeding not associated with sexual precocity is a common presenting sign. Treatment consists of hysterectomy, with removal of the ovaries, followed by adjunctive radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, depending on the operative findings.

Vagina

Sarcoma botryoides is a variant of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma that occurs most commonly in the vagina of pediatric patients. Sarcoma botryoides tends to arise in the anterior wall of the vagina and manifests as a submucosal lesion that is grape-like in appearance; if located at the cervix it could resemble a cervical polyp or polypoid mass. These lesions were formerly treated with exenterative procedures; equal success has occurred with less-radical surgery (polypectomy, conization, and local excision) and adjuvant chemotherapy with or without radiotherapy. A combination of vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide appears to be effective. Outcomes depend on tumor size, extent of disease at time of diagnosis, and histologic subtype. The 5-year survival rates for patients with clinical stages I-IV were 83%, 70%, 52%, and 25%, respectively.

Vaginal adenosis can lead to the development of clear cell adenocarcinoma of the vagina in females exposed to diethylstilbestrol (DES) in utero. Pregnant women at risk for miscarriage are no longer exposed to DES, and thus fewer adolescent girls and young women are at risk for this unusual tumor.

A rare tumor occurring in the vagina of infants is the endodermal sinus tumor. This disease usually occurs in children <2 yr of age, and survival rates are poor. Combination surgery and chemotherapy are appropriate. Benign papillomas can arise in the vagina of children and result in vaginal bleeding. Rarely, vaginal bleeding is secondary to leukemia or a hemangioma.

Vulva

Any questionable vulvar lesion should be biopsied and submitted for histologic examination. Lipoma, liposarcoma, and malignant melanoma of the vulva have been reported in young patients. The most common lesion is likely condyloma acuminata, associated with the human papilloma virus (HPV) (Chapter 258). Diagnosis is usually made by visual inspection. Treatment consists of observation for spontaneous regression, topical trichloroacetic acid, local cryotherapy, electrocautery, excision, and laser ablation. Some products used to treat skin lesions in adults have not been approved for children, including provider application of podophyllin resin and home application of imiquimod, podophlox, and sinecatechin ointment.

Cervix

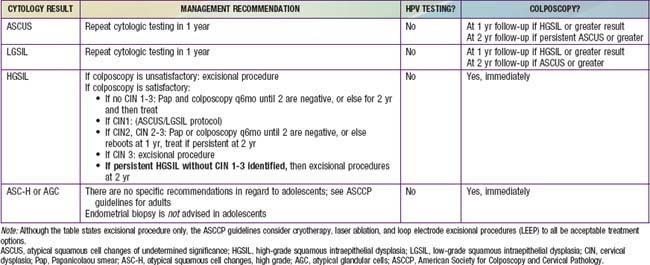

Historically, cervical cancer screening has been cytology based using the Papanicolaou (Pap) test and Bethesda Classification System (Table 547-3). Advances in epidemiologic research and molecular techniques have allowed the identification of the integral role of HPV in development of cervical cancer. HPV has become an important factor in the interpretation of cytologic results and subsequent management. The discovery of HPV presents a unique target for cervical cancer prevention, with the pediatric and adolescent population at the forefront of its implementation. A vaccine is available against the 2 HPV strains most commonly associated with cervical cancer (HPV 16, HPV 18). It is thought to be 100% effective against these 2 subtypes and to prevent up to 70% of cervical cancers. The ACOG recommends vaccination for all girls and women aged 9-26 yr, and The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/acip/) recommends routine vaccination of girls aged 11-12 yr with 3 doses of quadrivalent HPV vaccine, starting as early as 9 yr. Catch-up vaccination is indicated for girls and women aged 13-26 yr who have not been fully vaccinated. Female patients should be vaccinated even if sexually exposed; vaccination prior to exposure is ideal. Pap testing and screening for HPV DNA or HPV antibody is not required before vaccination. ACOG recommends that cervical cancer screening of women who have been immunized against HPV-16 and HPV-18 should not differ from that of nonimmunized women and should follow the exact same regimen.

The adolescent population presents a unique challenge to cervical cancer screening, because the prevalence of HPV is high. In adolescents aged 15-19 yr, HPV cumulative incidence rates after initiation of sexual activity have been reported as 17% at 1 yr and 35.7% at 3 yr. Correlating with the natural history of an HPV infection, >90% of low-grade intraepithelial lesions regress within this age group, giving the presence of HPV in this population little clinical significance. The overall incidence of a high-grade lesion on Pap test in the adolescent population remains low (0.7%); cervical cancer is uncommon in the age group. The SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975-2006 published by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) reports an incidence of invasive cervical cancer as 0.1/100,000 in 15-19 yr olds, with no cases reported before the age of 15 yr; colposcopy for minor cytologic abnormalities within this age group should be highly discouraged, because it will result more often in harm than produce any clinical benefit.

The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists guidelines recommend that adolescents should be managed conservatively and should not receive Pap smear screening until age 21 yr regardless of age of onset of sexual intercourse. If an HPV test is done, the results should be ignored. However, sexually active immunocompromised (HIV positive patients or organ transplant recipients) adolescents should undergo screening twice within the first year after diagnosis and annually thereafter. Table 547-3 demonstrates management recommendations for abnormal cytologic results within the adolescent population.

Clinic protocols that require teenagers to undergo Pap smears before prescribing contraceptives should be reconsidered in light of these recommendations.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Committee on Adolescent Health Care. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 436: evaluation and management of abnormal cervical cytology and histology in adolescents. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(6):1422-1425.

Anders JF, Powell EC. Urgency of evaluation and outcome of acute ovarian torsion in pediatric patients. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:532-535.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007;56:1-19.

Chow EJ, Friedman DL, Yasui Y, et al. Timing of menarche among survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50:854-858.

da Silva BB, Dos Santos AR, Bosco Parentes-Vieira J, et al. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma of the uterus associated with uterine inversion in an adolescent: A case report and published work review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2008;34:735-738.

da Silva KS, Kanumakala S, Grover SR, et al. Ovarian lesions in children and adolescents—an 11-year review. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2004;17:951-957.

Dalmau J, Gleichman AJ, Hughes EG, et al. Anti–NMDA-receptor encephalitis: case series and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:1091-1098.

Enriquez G, Duran C, Toran N, et al. Conservative versus surgical treatment for complex neonatal ovarian cysts: outcomes study. Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:501-508.

Fallat ME, Hutter J. Preservation of fertility in pediatric and adolescent patients with cancer. Pediatrics. 2008;121:e1461-e1469.

Green DM, Sklar CA, Boice JD, et al. Ovarian failure and reproductive outcomes after childhood cancer treatment: Results from the childhood cancer survivor study. Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2374-2381.

Gruessner SE, Omwandho CO, Dreyer T, et al. Management of stage I cervical sarcoma botryoides in childhood and adolescence. Eur J Pediatr. 2004;163:452-456.

Koularis CR, Penson RT. Ovarian stromal and germ cell tumors. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:126-136.

Lee SJ, Schover LR, Patridge AH, et al. American society of clinical oncology recommendations on fertility preservation in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1-14.

Orbak Z, Kantarci M, Yildirim ZK, et al. Ovarian volume and uterine length in neonatal girls. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2007;20:397-403.

Stepanian M, Cohn DE. Gynecologic malignancies n adolescents. Adolesc Med. 2004;15:549-568.

Wright TCJr, Massad S, Dunton CJ, et al. 2006 consensus guideline for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:346-355.

Updated Information on Cancer Statistics

National Cancer Institute. Surveillance, epidemiology and end results (website), http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/index.html. Accessed April 1, 2010

National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Review 1975–2006 (website), http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2006/index.html. Accessed April 1, 2010

Updated Information about HPV, Cervical Cancer, and HPV Vaccine

American Cancer Society. Home page (website) http://www.cancer.org/docroot/home/index.asp Accessed April 1, 2010

American Social Health Association. HPV and Cervical Cancer Prevention Resource Center (website), http://www.ashastd.org/hpv/hpv_overview.cfm. Accessed April 1, 2010

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccines and preventable diseases: HPV vaccination: human papillomavirus (HPV) (website), http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/hpv/default.htm. Accessed April 1, 2010

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer prevention and control (website), http://www.cdc.gov/cancer. Accessed April 1, 2010

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Human papillomavirus (HPV) (website), http://www.cdc.gov/hpv/. Accessed April 1, 2010

National Cancer Institute. HPV (human papillomavirus) vaccines for cervical cancer (website), http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/hpv-vaccines. Accessed April 1, 2010