Chapter 618 Disorders of the Conjunctiva

Conjunctivitis

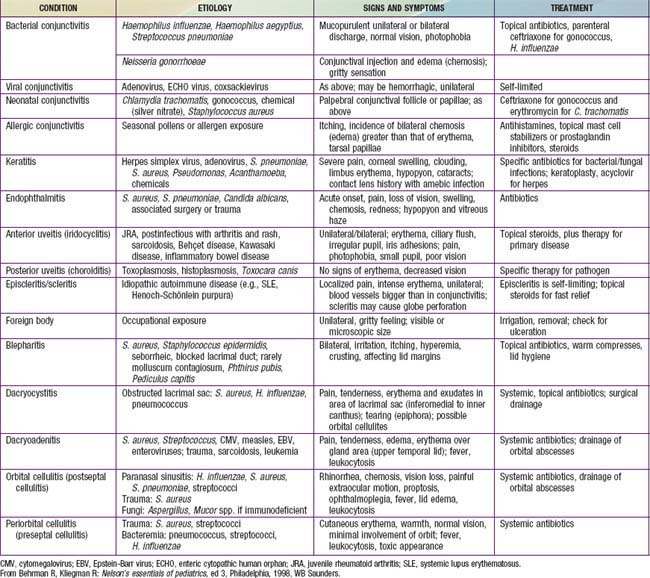

The conjunctiva reacts to a wide range of bacterial and viral agents, allergens, irritants, toxins, and systemic diseases. Conjunctivitis is common in childhood and may be infectious or noninfectious. The differential diagnosis of a red-appearing eye includes conjunctival as well as other ocular sites (Table 618-1).

Ophthalmia Neonatorum

This form of conjunctivitis, occurring in infants younger than 4 wk of age, is the most common eye disease of newborns. Its many different causal agents vary greatly in their virulence and outcome. Silver nitrate instillation may result in a mild self-limited chemical conjunctivitis, whereas Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Pseudomonas are capable of causing corneal perforation, blindness, and death. The risk of conjunctivitis in newborns depends on frequencies of maternal infections, prophylactic measures, circumstances during labor and delivery, and postdelivery exposure to microorganisms.

Epidemiology

Conjunctivitis during the neonatal period is usually acquired during vaginal delivery and reflects the sexually transmitted infections prevalent in the community. In 1880, 10% of European children developed gonococcal conjunctivitis at birth. Ophthalmia neonatorum was the leading cause of blindness during that period. The epidemiology of this condition changed dramatically in 1881, when Crede reported that 2% silver nitrate solution instilled in the eyes of newborns reduced the incidence of gonococcal ophthalmia from 10% to 0.3%.

During the 20th century, the incidence of gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum decreased in industrialized countries secondary to widespread use of silver nitrate prophylaxis and prenatal screening and treatment of maternal gonorrhea. Gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum has an incidence of 0.3/1,000 live births in the USA. In comparison, Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common organism causing ophthalmia neonatorum in the USA, with an incidence of 8.2/1,000 births.

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations of the various forms of ophthalmia neonatorum are not specific enough to allow an accurate diagnosis. Although the timing and character of the signs are somewhat typical for each cause of this condition, there is considerable overlap and physicians should not rely solely on clinical findings. Regardless of its cause, ophthalmia neonatorum is characterized by redness and chemosis (swelling) of the conjunctiva, edema of the eyelids, and discharge, which may be purulent.

Neonatal conjunctivitis is a potentially blinding condition. The infection may also have associated systemic manifestations that require treatment. Therefore, any newborn infant who develops signs of conjunctivitis needs a prompt and comprehensive systemic and ocular evaluation to determine the agent causing the infection and the appropriate treatment.

The onset of inflammation caused by silver nitrate drops usually occurs within 6-12 hr after birth, with clearing by 24-48 hr. The usual incubation period for conjunctivitis due to N. gonorrhoeae is 2-5 days, and for that due to C. trachomatis, it is 5-14 days. Gonococcal infection may be present at birth or be delayed beyond 5 days of life owing to partial suppression by ocular prophylaxis. Gonococcal conjunctivitis may also begin in infancy after inoculation by the contaminated fingers of adults. The time of onset of disease with other bacteria is highly variable.

Gonococcal conjunctivitis begins with mild inflammation and a serosanguineous discharge. Within 24 hr, the discharge becomes thick and purulent, and tense edema of the eyelids with marked chemosis occurs. If proper treatment is delayed, the infection may spread to involve the deeper layers of the conjunctivae and the cornea. Complications include corneal ulceration and perforation, iridocyclitis, anterior synechiae, and rarely panophthalmitis. Conjunctivitis caused by C. trachomatis (inclusion blennorrhea) may vary from mild inflammation to severe swelling of the eyelids with copious purulent discharge. The process involves mainly the tarsal conjunctivae; the corneas are rarely affected. Conjunctivitis due to Staphylococcus aureus or other organisms is similar to that produced by C. trachomatis. Conjunctivitis due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa is uncommon, acquired in the nursery, and a potentially serious process. It is characterized by the appearance on days 5-18 of edema, erythema of the lids, purulent discharge, pannus formation, endophthalmitis, sepsis, shock, and death.

Diagnosis

Conjunctivitis appearing after 48 hr should be evaluated for a possibly infectious cause. Gram stain of the purulent discharge should be performed and the material cultured. If a viral cause is suspected, a swab should be submitted in tissue culture media for virus isolation. In chlamydial conjunctivitis, the diagnosis is made by examining Giemsa-stained epithelial cells scraped from the tarsal conjunctivae for the characteristic intracytoplasmic inclusions, by isolating the organisms from a conjunctival swab using special tissue culture techniques, by immunofluorescent staining of conjunctival scrapings for chlamydial inclusions, or by tests for chlamydial antigen or DNA. The differential diagnosis of ophthalmia neonatorum includes dacryocystitis caused by congenital nasolacrimal duct obstruction with lacrimal sac distention (dacryocystocele).

Treatment

Treatment of infants in whom gonococcal ophthalmia is suspected and the Gram stain shows the characteristic intracellular gram-negative diplococci should be initiated immediately with ceftriaxone, 50 mg/kg/24 hr for 1 dose, not to exceed 125 mg. The eye should also be irrigated initially with saline every 10-30 min, gradually increasing to 2-hr intervals until the purulent discharge has cleared. An alternative regimen includes cefotaxime (100 mg/kg/24 hr given IV or IM every 12 hr for 7 days or 100 mg/kg as a single dose). Treatment is extended if sepsis or other extraocular sites are involved (meningitis, arthritis). Neonatal conjunctivitis secondary to Chlamydia is treated with oral erythromycin (50 mg/kg/24 hr in 4 divided doses) for 2 wk. This cures conjunctivitis and may prevent subsequent chlamydial pneumonia. Pseudomonas neonatal conjunctivitis is treated with systemic antibiotics, including an aminoglycoside, plus local saline irrigation and gentamicin ophthalmic ointment. Staphylococcal conjunctivitis is treated with parenteral methicillin and local saline irrigation.

Prognosis and Prevention

Before the institution of topical ophthalmic prophylaxis at birth, gonococcal ophthalmia was a common cause of blindness or permanent eye damage. If properly applied, this form of prophylaxis is highly effective unless infection is present at birth. Drops of 0.5% erythromycin or 1% silver nitrate are instilled directly into the open eyes at birth using wax or plastic single-dose containers. Saline irrigation after silver nitrate application is unnecessary. Silver nitrate is ineffective against active infection and may have limited use against Chlamydia. Povidone-iodine (2% solution) may also be an effective prophylactic agent.

Identification of maternal gonococcal infection and appropriate treatment has become a standard element of routine prenatal care. An infant born to a woman who has untreated gonococcal infection should receive a single dose of ceftriaxone, 50 mg/kg (maximum 125 mg) IV or IM, in addition to topical prophylaxis. The dose should be reduced for premature infants. Penicillin (50,000 U) should be used if the mother’s gonococcal isolate is known to be penicillin sensitive.

Neither topical prophylaxis nor topical treatment prevents the afebrile pneumonia that occurs in 10-20% of infants exposed to C. trachomatis. Although chlamydial conjunctivitis is often a self-limiting disease, chlamydial pneumonia may have serious consequences. It is important that infants with chlamydial disease receive systemic treatment. Treatment of colonized pregnant women with erythromycin may prevent neonatal disease.

Acute Purulent Conjunctivitis

This is characterized by more or less generalized conjunctival hyperemia, edema, mucopurulent exudate, glued eyes (lids stuck together after sleeping), and various degrees of ocular pain and discomfort. It is usually a result of bacterial infection. The most frequent causes are nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (associated with ipsilateral otitis media), pneumococci, staphylococci, and streptococci. Bacterial purulent conjunctivitis, especially due to pneumococcus or H. influenzae may occur in epidemics. Conjunctival smear and culture are helpful in differentiating specific types. These common forms of acute purulent conjunctivitis usually respond well to warm compresses and frequent topical instillation of antibiotic drops. Brazilian purpuric fever due to Haemophilus aegyptius manifests as conjunctivitis and sepsis. N. gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia are relatively common causes of acute purulent conjunctivitis in children beyond the newborn period, especially in adolescents. These infections require specific testing and treatment. Patients with a low risk of bacterial conjunctivitis have been characterized as >6 yr of age, becoming ill between April and November, having minimal or a watery discharge, and not having morning glue eye.

Viral Conjunctivitis

This is generally characterized by a watery discharge. Follicular changes (small aggregates of lymphocytes) are often found in the palpebral conjunctiva. Conjunctivitis resulting from adenovirus infection is relatively common, sometimes with corneal involvement as well as pharyngitis or pneumonia. Outbreaks of conjunctivitis caused by enterovirus are also encountered; this type may be hemorrhagic. Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis may be epidemic due to enterovirus CA24 or 70 and is characterized by red, swollen, and painful eyes with a hemorrhagic watery discharge. Conjunctivitis is commonly associated with such systemic viral infections as the childhood exanthems, particularly measles. Viral conjunctivitis is usually self-limited.

Epidemic Keratoconjunctivitis

This is caused by adenovirus type 8 and is transmitted by direct contact. It initially presents as a sensation of a foreign body beneath the lids, with itching and burning. Edema and photophobia develop rapidly, and large oval follicles appear within the conjunctiva. Preauricular adenopathy and a pseudomembrane on the conjunctival surface occur frequently. Subepithelial corneal infiltrates may develop and may cause blurring of vision; these usually disappear but may permanently reduce visual acuity. Corneal complications are less common in children than in adults. Children may have associated upper respiratory tract infection and pharyngitis. No specific medical therapy is available to decrease the symptoms or shorten the course of the disease. Emphasis must be placed on prevention of spread of the disease. Replicating virus is present in 95% of patients 10 days after the appearance of symptoms.

Membranous and Pseudomembranous Conjunctivitis

These types of conjunctivitis can be encountered in a number of diseases. The classic membranous conjunctivitis is that of diphtheria, accompanied by a fibrin-rich exudate that forms on the conjunctival surface and permeates the epithelium; the membrane is removed with difficulty and leaves raw bleeding areas. In pseudomembranous conjunctivitis, the layer of fibrin-rich exudate is superficial and can often be stripped easily, leaving the surface smooth. This type occurs with many bacterial and viral infections, including staphylococcal, pneumococcal, streptococcal, or chlamydial conjunctivitis, and in epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. It is also found in vernal conjunctivitis and in Stevens-Johnson disease.

Allergic Conjunctivitis

This is usually accompanied by intense itching, clear watery discharge, and conjunctival edema. It is commonly seasonal. Cold compresses and decongestant drops give symptomatic relief. Topical mast cell stabilizers or prostaglandin inhibitors may also help. In selected cases, topical corticosteroids are used under an ophthalmologist’s supervision.

Vernal Conjunctivitis

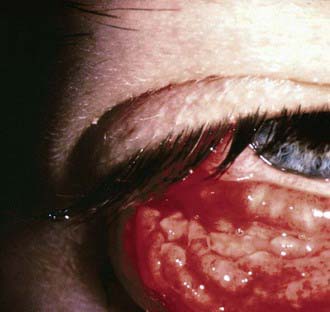

This usually begins in the prepubertal years and may recur for many years. Atopy appears to have a role in its origin, but the pathogenesis is uncertain. Extreme itching and tearing are the usual complaints. Large, flattened, cobblestone-like papillary lesions of the palpebral conjunctivae are characteristic (Fig. 618-1). A stringy exudate and a milky conjunctival pseudomembrane are frequently present. Small elevated lesions of the bulbar conjunctiva adjacent to the limbus (limbal form) may be found. Smear of the conjunctival exudate reveals many eosinophils. Topical corticosteroid therapy and cold compresses afford some relief. Topical mast cell stabilizers or prostaglandin inhibitors are useful when long-term control is needed. The long-term use of corticosteroids should be avoided.

Parinaud Oculoglandular Syndrome

This represents a form of cat-scratch disease and is caused by Bartonella henselae, which is transmitted from cat to cat by fleas (Chapter 201). Kittens are more likely than adult cats to be infected. Humans can become infected when they are scratched by a cat. In addition, bacteria may pass from a cat’s saliva to its fur during grooming. The bacteria can then be deposited on the conjunctiva after rubbing one’s eyes after handling the cat. Lymphadenopathy and conjunctivitis are hallmarks of the disease. Conjunctival granulomas may develop (Fig. 618-2). The course is generally self-limited, but antibiotics may be used in some cases.

Chemical Conjunctivitis

This can result when an irritating substance enters the conjunctival sac (as in the acute but benign conjunctivitis caused by silver nitrate in newborns). Other common offenders are household cleaning substances, sprays, smoke, smog, and industrial pollutants. Alkalis tend to linger in the conjunctival tissues and continue to inflict damage for hours or days. Acids precipitate the proteins in tissues and so produce their effect immediately. In either case, prompt, thorough, and copious irrigation is crucial. Extensive tissue damage, even loss of the eye, can result, especially if the offending agent is an alkali.

Other Conjunctival Disorders

Subconjunctival hemorrhage is manifested by bright or dark red patches in the bulbar conjunctiva and may result from injury or inflammation. It commonly occurs spontaneously. It may occasionally result from severe sneezing or coughing. Rarely, it may be a manifestation of a blood dyscrasia. Subconjunctival hemorrhages are self-limiting and require no treatment.

Pinguecula is a yellowish-white, slightly elevated mass on the bulbar conjunctiva, usually in the interpalpebral region. It represents elastic and hyaline degenerative changes of the conjunctiva. No treatment is required except for cosmetic reasons, in which case simple excision suffices.

Pterygium is a fleshy triangular conjunctival lesion that may encroach on the cornea. It typically occurs in the nasal interpalpebral region. The pathologic findings are similar to those of a pinguecula. The development of pterygia is related to exposure to ultraviolet light, and it therefore is more commonly found among people who live near the equator. Removal is suggested when the lesion encroaches far onto the cornea. Recurrence after removal is common.

Dermoid cyst and dermolipoma are benign lesions, clinically similar in appearance. They are smooth, elevated, round to oval lesions of various sizes. The color varies from yellowish white to fleshy pink. The most frequent site is the upper outer quadrant of the globe; they also commonly occur near or straddling the limbus. Dermolipoma is composed of adipose and connective tissue. Dermoid cysts may also contain glandular tissue, hair follicles, and hair shafts. Excision for cosmetic reasons is feasible. Dermolipomas are often connected to the extraocular muscles, making their complete removal impossible without sacrificing ocular motility.

Conjunctival nevus is a small, slightly elevated lesion that may vary in pigmentation from pale salmon to dark brown. It is usually benign, but careful observation for progressive growth or changes suggestive of malignancy is advised.

Symblepharon is a cicatricial adhesion between the conjunctiva of the lid and the globe; the lower lid is usually affected. It follows operation or injuries, especially burns from lye, acids, or molten metals. It is a serious complication of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. It may interfere with motion of the eyeball and may cause diplopia. The adhesions should be separated and the raw surfaces kept from uniting during healing. Grafts of oral mucous membrane may be necessary.

Atik B, Thanh TTK, Luong VQ, et al. Impact of annual targeted treatment of infectious trachoma and susceptibility to reinfection. JAMA. 2006;296:1488-1497.

Bremond-Gignac D, Mariani-Kurkdjian P, Beresniak A, et al. Efficacy and safety of azithromycin 1.5% eye drops for purulent bacterial conjunctivitis in pediatric patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:222-226.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis outbreaks caused by coxsackievirus A24v—Uganda and Southern Sudan, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1024.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Outbreak of bacterial conjunctivitis at a college—New Hampshire, January-March, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:205-208.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis outbreak caused by coxsackievirus A24—Puerto Rico, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53:632.

Chang DC, Grant GB, O’Donnell K, et al. Multistate outbreak of fusarium keratitis associated with use of a contact lens solution. JAMA. 2006;296:953-963.

Everitt HA, Little PS, Smith PWF. A randomised controlled trial of management strategies for acute infective conjunctivitis in general practice. BMJ. 2006;333:321-324.

House JI, Ayele B, Porco TC, et al. Assessment of herd protection against trachoma due to repeated mass antibiotic distributions: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1111-1118.

The Medical Letter. Ophthalmic besifloxacin (Besivance). Med Lett. 2009;51:101-102.

The Medical Letter. Ophthalmic azithromycin (Azasite). Med Lett. 2008;50:1279-1280.

Meltzer JA, Kunkov S, Crain EF. Identifying children at low risk for bacterial conjunctivitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:263-267.

O’Hara MA. Ophthalmia neonatorum. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1993;40:715.

Porco TC, Gebre T, Ayele B, et al. Effect of mass distribution of azithromycin for trachoma control on overall mortality in Ethiopian children. JAMA. 2009;302:962-968.

Rietveld RP, ter Riet G, Bindels PJE, et al. Predicting bacterial cause in infectious conjunctivitis: cohort study on informativeness of combinations of signs and symptoms. Br Med J. 2004;329:206-208.

Rose PW, Hamden A, Brueggemann AB, et al. Chloramphenicol treatment for acute infective conjunctivitis in children in primary care: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:37-42.

Shiuey Y, Ambati BK, Adamis AP, et al. A randomized, double-masked trial of topical ketorolac versus artificial tears for treatment of viral conjunctivitis. Ophthalmology. 2000;107:1512-1517.

Weiss A, Brinser JH, Nazar-Stewart V. Acute conjunctivitis in childhood. J Pediatr. 1993;122:10-14.