Chapter 625 Orbital Abnormalities

Hypertelorism and Hypotelorism

Hypertelorism is wide separation of the eyes or an increased interorbital distance, which can occur as a morphogenetic variant, a primary deformity, or a secondary phenomenon in association with developmental abnormalities, such as frontal meningocele or encephalocele or the persistence of a facial cleft. Often associated are strabismus, generally exotropia, and sometimes optic atrophy.

Hypotelorism refers to narrowness of the interorbital distance, which can occur as a morphogenetic variant alone or in association with other anomalies, such as epicanthus or holoprosencephaly or secondary to a cranial dystrophy, such as scaphocephaly.

Exophthalmos and Enophthalmos

Protrusion of the eye is referred to as exophthalmos or proptosis and is a common indicator of orbital disease. It may be caused by shallowness of the orbits, as in many craniofacial malformations, or by increased tissue mass within the orbit, as with neoplastic, vascular, and inflammatory disorders. Ocular complications include exposure keratopathy, ocular motor disturbances, and optic atrophy with loss of vision.

Posterior displacement or sinking of the eye back into the orbit is referred to as enophthalmos. This can occur with orbital fracture or with atrophy of orbital tissue.

Orbital Inflammation

Inflammatory disease involving the orbit may be primary or secondary to systemic disease. Idiopathic orbital inflammation (orbital pseudotumor) represents a wide spectrum of clinical entities. Symptoms at the time of presentation can include pain, eyelid swelling, proptosis, a red eye, and fever. The inflammation can involve a single extraocular muscle (myositis) or the entire orbit. Orbital apex syndrome is a serious condition that can also involve the cavernous sinus and can compress or displace the optic nerve. Confusion with orbital cellulitis is common but can be differentiated by the lack of associated sinus disease, its appearance on CT scan, and lack of improvement with systemic antibiotics. Orbital pseudotumor is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, Crohn disease, myasthenia gravis, and lymphoma. Treatment includes the use of high-dose systemic corticosteroids. Often, the symptoms improve dramatically shortly after treatment is initiated. Bilateral involvement, associated uveitis, disc edema, and recurrence of inflammation are not uncommon in the pediatric population. Immunotherapy or radiation treatment may be necessary for resistant or recurrent cases.

Thyroid-related ophthalmopathy is thought to be secondary to an immune mechanism, leading to inflammation and deposition of mucopolysaccharides and collagen in the extraocular muscles and orbital fat. Involvement of the extraocular muscles can lead to a restrictive strabismus. Lid retraction and exophthalmos can cause corneal exposure and infection or perforation. Involvement of the posterior orbit can compress the optic nerve. Treatment of thyroid-related ophthalmopathy may include the use of systemic corticosteroids, radiation of the orbit, eyelid surgery, strabismus surgery, or orbital decompression to eliminate symptoms and protect vision. The degree of orbital involvement is often independent of the status of the systemic disease (Chapter 562).

Other systemic disorders that can cause inflammatory disease within the orbit include lymphoma, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, polyarteritis nodosa, systemic lupus erythematosus, dermatomyositis, Wegener granulomatosis, and juvenile xanthogranuloma.

Tumors of the Orbit

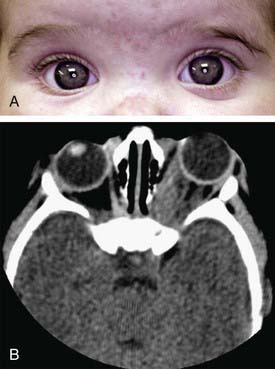

Various tumors occur in and about the orbit in childhood. Among benign tumors, the most common are vascular lesions (principally hemangiomas) (Fig. 625-1) and dermoids. Among malignant neoplasms, rhabdomyosarcoma, lymphosarcoma, and metastatic neuroblastoma are the most common. Optic nerve gliomas are most often seen in patients with neurofibromatosis and can manifest with poor vision or proptosis. Retinoblastoma can extend into the orbit if it is discovered late or if it goes untreated. Teratomas are rare tumors that typically grow rapidly after birth and exhibit explosive proptosis.

Figure 625-1 Orbital hemangioma. A, Note the proptosis. B, CT scan.

(Courtesy of Amy Nopper, MD, and Brandon Newell, MD.)

The effects of orbital tumors vary with their locations and growth patterns. The principal signs are proptosis, resistance to retroplacement of the eye, and impairment of eye movement. A palpable mass may be found. Other significant signs are ptosis, optic nerve head congestion, optic atrophy, and loss of vision. Bruit and visible pulsation of the globe are important clues to vascular lesions.

Evaluation of orbital tumors includes ultrasonography, MRI, and CT. Pseudotumor of the orbit also must be considered in children with signs of a mass lesion. In selected cases, an incisional or excisional biopsy of the lesion may be warranted.

Gorospe L, Royo A, Berrocal T, et al. Imaging of orbital disorders in pediatric patients. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:2012-2026.

Krassas GE. Childhood Graves’ disease and its ophthalmic complications: some sensitive issues. J Endocrinol Invest. 2008;31:582.

Ohtsuka K, Hashimoto M, Suzuki Y. A review of 244 orbital tumors in Japanese patients during a 21-year period: origins and locations. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2005;49:49-55.

Russo V, Scott IU, Querques G, et al. Orbital and ocular manifestations of acute childhood leukemia: clinical and statistical analysis of 180 patients. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2008;18:619-623.

Shields JA, Shields CL, Scartozzi R. Survey of 1264 patients with orbital tumors and simulating lesions: the 2002 Montgomery Lecture, part 1. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:997-1008.

Yuen SJA, Rubin PAD. Idiopathic orbital inflammation. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:491-499.