Chapter 651 Diseases of the Dermis

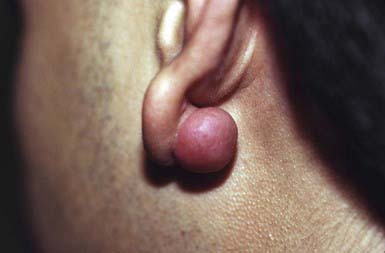

Keloid

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Keloids are usually induced by trauma and commonly follow ear piercing, burns, scalds, and surgical procedures. Certain individuals are predisposed to keloid formation; a familial tendency (recessive or dominant inheritance) or the presence of foreign material in the wound may have a pathogenic role. Keloids are a rare feature of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, and pachydermoperiostosis. Keloids result from an abnormal fibrous wound healing response in which tissue repair and regeneration-regulation control mechanisms are lost. Collagen production is 20 times that seen in normal scars and the type I/type III collagen ratio is abnormally high. In keloids, tissue values of tumor growth factor-β (TGF-β) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) are elevated; fibroblasts are more sensitive to their effects, and their degradation rate is decreased.

Clinical Manifestations

A keloid is a sharply demarcated, benign, dense growth of connective tissue that forms in the dermis after trauma. The lesions are firm, raised, pink, and rubbery; they may be tender or pruritic. Sites of predilection are the face, earlobes (Fig. 651-1), neck, shoulders, upper trunk, sternum, and lower legs. In both keloids and hypertrophic scars, new collagen forms over a much longer period than in wounds that heal normally.

Differential Diagnosis

Keloids should be differentiated from hypertrophic scars, which remain confined to the site of injury and gradually involute over time.

Treatment

Young keloids may diminish in size if injected intralesionally at 4-wk intervals with triamcinolone suspension (10-40 mg/mL). At times, a more concentrated suspension is required. Large or old keloids may require surgical excision followed by intralesional injections of corticosteroid. The risk of recurrence at the same site argues against surgical excision alone, although ear lobe keloids respond well to surgical excision, pressure dressings, and intralesional steroids. Placement of topical silicon gel sheeting over the keloid for several hours per day for several weeks may help in some patients.

Striae Cutis Distensae (Stretch Marks)

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Striae formation is common in adolescence. The most frequent causes are rapid growth, pregnancy, obesity, Cushing disease, and prolonged corticosteroid therapy. The pathogenesis is unknown, but the occurrence of alterations in elastic fibers is thought to be the primary process.

Clinical Manifestations

These thinned, depressed, erythematous bands of atrophic skin eventually become silvery, opalescent, and smooth. They occur most frequently in areas that have been subject to distention, such as the lower back (Fig. 651-2), buttocks, thighs, breasts, abdomen, and shoulders.

Corticosteroid-Induced Atrophy

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Both topical and systemic corticosteroid treatment can result in cutaneous atrophy. This is particularly common when a potent or superpotent topical corticosteroid is applied under occlusion or to an intertriginous area for a prolonged period. Keratinocyte growth is decreased, but epidermal maturation is accelerated, resulting in a thinning of the epidermis and stratum corneum. Fibroblast growth and function are also decreased, leading to the dermal changes. The mechanism involves inhibition of synthesis of collagen type I, noncollagenous proteins, and total protein content of the skin, along with progressive reduction of dermal proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans.

Clinical Manifestations

Affected skin is thin, fragile, smooth, and semitransparent, with telangiectasias and loss of normal skin markings.

Granuloma Annulare

Etiology/Pathogenesis

The cause of granuloma annulare is unknown. Some cases of granuloma annulare, particularly the generalized form, may be associated with diabetes mellitus or with anterior uveitis. However, most cases are seen in healthy children.

Clinical Manifestations

This common dermatosis occurs predominantly in children and young adults. Affected children are usually healthy. Typical lesions begin as firm, smooth, erythematous papules. They gradually enlarge to form annular plaques with a papular border and a normal, slightly atrophic or discolored central area up to several centimeters in size. Lesions may occur anywhere on the body, but mucous membranes are spared. Favored sites include the dorsum of the hands (Fig. 651-3) and feet. The disseminated papular form is rare in children. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare tends to develop on the scalp and limbs, particularly in the pretibial area. These lesions are firm, usually nontender, skin-colored nodules. Perforating granuloma annulare is characterized by the development of a yellowish center in some of the superficial papular lesions as a result of transepidermal elimination of altered collagen.

Differential Diagnosis

Annular lesions are often mistaken for tinea corporis because of the elevated advancing border. They differ in that they are not scaly. Papular lesions, another variant, may simulate rheumatoid nodules, particularly when grouped on the fingers and elbows.

Histology

The lesion of granuloma annulare consists of a granuloma with a central area of necrotic collagen; mucin deposition; and a peripheral palisading infiltrate of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and foreign body giant cells. The pattern resembles that of necrobiosis lipoidica and rheumatoid nodule, but subtle histologic differences usually permit differentiation.

Treatment

The eruption persists for months to years, but spontaneous resolution without residual change is usual; 50% of lesions clear within 2 years. Application of a potent or superpotent topical corticosteroid preparation or intralesional injections (5-10 mg/mL) of corticosteroid may hasten involution, but nonintervention is usual.

Necrobiosis Lipoidica

Etiology/Pathogenesis

The cause of necrobiosis lipoidica is unknown, but 50-75% of patients have diabetes mellitus; necrobiosis lipoidica occurs in 0.3% of all diabetic patients.

Clinical Manifestations

This disorder manifests as erythematous papules that evolve into irregularly shaped, sharply demarcated, yellow, sclerotic plaques with central telangiectasia and a violaceous border. Scaling, crusting, and ulceration are frequent. Lesions develop most commonly on the shins (Fig. 651-4). Slow extension of a given lesion over the years is usual, but long periods of quiescence or complete healing with scarring may occur.

Histology

Poorly defined areas of necrobiotic collagen are seen throughout, but primarily low in the dermis, associated with mucin deposition. Surrounding the necrobiotic, disordered areas of collagen is a palisading lymphohistiocytic granulomatous infiltrate. Some lesions are more characteristically granulomatous, with limited necrobiosis of collagen.

Lichen Sclerosus

Clinical Manifestations

Lichen sclerosus manifests initially as shiny, indurated, ivory-colored papules, often with a violaceous halo. The surface shows prominent dilated pilosebaceous or sweat duct orifices that often contain yellow or brown plugs. The papules coalesce to form irregular plaques of variable size, which may develop hemorrhagic bullae in their margins. In the later stages, atrophy results in a depressed plaque with a wrinkled surface. This disorder occurs more commonly in girls than in boys. Sites of predilection in girls are the vulvar (Fig. 651-5), perianal, and perineal skin. Extensive involvement may produce a sclerotic, atrophic plaque of hourglass configuration; shrinkage of the labia and stenosis of the introitus may result. Vaginal discharge precedes vulvar lesions in approximately 20% of patients. In boys, the prepuce and glans penis are often involved, usually in association with phimosis; most boys with the disorder were not circumcised early in life. Sites elsewhere on the body that are most commonly involved include the upper trunk, the neck, the axillae, the flexor surfaces of wrists, and the areas around the umbilicus and the eyes. Pruritus may be severe.

Differential Diagnosis

In children, lichen sclerosus is most frequently confused with focal morphea (Chapter 154), with which it may coexist. In the genital area, it may be mistakenly attributed to sexual abuse.

Histology

Biopsy is diagnostic, revealing hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging, hydropic degeneration of basal cells, a bandlike dermal lymphocytic infiltrate, homogenized collagen, and thinned elastic fibers in the upper dermis.

Treatment

Vulvar lichen sclerosus in childhood usually improves with puberty but does not usually resolve, and symptoms can recur throughout life. Long-term observation for the development of squamous cell carcinoma is necessary. Superpotent topical corticosteroids provide relief from pruritus and produce clearing of lesions, including those in the genital area. Topical tacrolimus and pimecrolimus have also been used. It is not known how response to treatment affects long-term cancer risk.

Morphea

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Morphea is a sclerosing condition of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue of unknown etiology.

Clinical Manifestations

Morphea is characterized by solitary, multiple or linear circumscribed areas of erythema that evolve into indurated, sclerotic, atrophic plaques (Fig. 651-6), later healing, or “burning out” with pigment change. It is seen more commonly in females. The most common types of morphea are plaque and linear. Morphea can affect any area of skin. When confined to the frontal scalp, forehead, and midface in a linear band, it is referred to as en coup de sabre. When located on one side of the face, it is called progressive hemifacial atrophy. These forms of morphea carry a poorer prognosis because of the associated underlying musculoskeletal atrophy that can be cosmetically disfiguring. Linear morphea over a joint may lead to restriction of mobility (Fig. 651-7). Pansclerotic morphea is a rare severe disabling variant.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of morphea includes granuloma annulare, necrobiosis lipoidica, lichen sclerosis, and late-stage Lyme disease (acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans).

Treatment

Morphea tends to persist, with gradual outward expansion on the skin for 3-5 yr until spontaneous cessation of the inflammatory phase occurs. Topical calcipotriene alone or in combination with high- to super-potency topical steroids or topical tacrolimus have been used for less severe disease. For the various forms of linear morphea and for severe plaque morphea, ultraviolet A-1 (UVA-1) phototherapy, methotrexate 0.3-0.5 mg/kg/week, and glucocorticosteroids 1 mg/kg/day may halt progression and help shorten the disease course. There are no comparison studies to suggest which therapy is optimal. Physical therapy is needed in linear morphea over a joint to maintain mobility. Significant postinflammatory pigment alteration may persist for years.

Scleredema (Scleredema Adultorum, Scleredema of Buschke)

Etiology/Pathogenesis

The cause of scleredema is unknown. There are 3 types. Type I (55% of cases) is preceded by a febrile illness. Type 2 (25%) is associated with paraproteinemias, including multiple myeloma. Type 3 (20%) is seen in diabetes mellitus.

Clinical Manifestations

Fifty percent of patient with scleredema are younger than 20 yr and almost always have type 1. Onset of type 1 is sudden, with brawny edema of the face and neck that spreads rapidly to involve the thorax and arms in a sweater distribution; the abdomen and legs are usually spared. The face acquires a waxy, masklike appearance. The involved areas feel indurated and woody, are nonpitting, and are not sharply demarcated from normal skin. The overlying skin is normal in color and is not atrophic.

Onset in patients with type 2 and type 3 scleredema may occur insidiously. Systemic involvement, which is uncommon and usually associated with types 2 and 3, is marked by thickening of the tongue; dysarthria; dysphagia; restriction of eye and joint movements; and pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal effusions. Electrocardiographic changes may also be observed. Laboratory data are not helpful.

Differential Diagnosis

Scleredema must be differentiated from scleroderma (Chapter 154), morphea, myxedema, trichinosis, dermatomyositis, sclerema neonatorum, and subcutaneous fat necrosis.

Lipoid Proteinosis (Urbach-Wiethe Disease, Hyalinosis Cutis et Mucosae)

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Lipoid proteinosis, an autosomal recessive disorder, is caused by mutations in the ECM-1 gene, which encodes the ECM-1 protein. ECM-1 (extracellular matrix protein) has a functional role in the structural organization of the dermis by binding to perlecan, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 9, and fibulin. Pathogenesis involves infiltration of hyaline material into the skin, oral cavity, larynx, and internal organs.

Clinical Manifestations

Lipoid proteinosis may be noted initially in early infancy as hoarseness. Skin lesions appear during childhood and consist of yellowish papules and nodules that may coalesce to form plaques. The classic sign is beaded papules on the eyelids. Lesions also occur on the face, forearms, neck, genitals, dorsum of the fingers, and scalp, where they result in patchy alopecia. Similar deposits are found on the lips, undersurface of the tongue, fauces, uvula, epiglottis, and vocal cords. The tongue becomes enlarged and feels firm on palpation. The patient may be unable to protrude the tongue. Pocklike atrophic scars may develop on the face. Hypertrophic, hyperkeratotic nodules occur at sites of friction, such as the elbows and knees; the palms may be diffusely thickened. The disease progresses until early adult life, but the prognosis is good. Symmetric ossification lateral to the sella turcica in the medial temporal region, identifiable roentgenographically, is pathognomonic but is not always present. Involvement of the larynx can lead to respiratory compromise, particularly in infancy, necessitating tracheostomy. Associated anomalies include dental abnormalities, epilepsy, and recurrent parotitis as a result of infiltrates in the Stensen duct. Virtually any organ can be involved.

Histology

The distinctive histologic pattern in lipoid proteinosis includes dilatation of dermal blood vessels and infiltration of homogeneous eosinophilic extracellular hyaline material along capillary walls and around sweat glands. Hyaline material in homogeneous bundles, diffusely arranged in the upper dermis, produces a thickened dermis. The infiltrates appear to contain both lipid and mucopolysaccharide substances.

Macular Atrophy (Anetoderma)

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Anetoderma is characterized by circumscribed areas of slack skin associated with loss of dermal substance. This disorder may have no associated underlying disease (primary macular atrophy) or may develop after an inflammatory skin condition. Secondary macular atrophy may be due to direct destruction of dermal elastin or elastolysis on an immunologic basis, especially the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, which are related to autoimmune disorders. The elastolysis may then be due to release of elastase from inflammatory cells.

Clinical Manifestations

Lesions vary from 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter and, if inflammatory, may initially be erythematous. They subsequently become thin, wrinkled, and blue-white or hypopigmented. The lesions often protrude as small outpouchings that, on palpation, may be readily indented into the subcutaneous tissue because of the dermal atrophy. Sites of predilection include the trunk, thighs, upper arms, and, less commonly, the neck and face. Lesions remain unchanged for life; new lesions often continue to develop for years.

Histology

All types of macular atrophy show focal loss of elastic tissue on histopathologic examination, a change that may not be recognized unless special stains are used.

Cutis Laxa (Dermatomegaly, Generalized Elastolysis)

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Cutis laxa is a heterogenous group of disorders related to abnormalities in elastic tissue. It may be autosomal recessive (type I—fibulin 5 and fibulin 4 genes, type II—ATP6V0A2 gene), autosomal dominant (elastin and fibulin 5 genes), X-linked (Cu (2+)-transporting ATPase, alpha polypeptide), or acquired. Acquired cutis laxa has developed after a febrile illness, inflammatory skin diseases such as lupus erythematosus or erythema multiforme, amyloidosis, urticaria, angioedema, and hypersensitivity reactions to penicillin, and in infants born to women who were taking penicillamine.

Clinical Manifestations

There may be widespread folds of lax skin, or changes may be mild and limited in extent, resembling anetoderma. Patients with severe cutis laxa have characteristic facial features, including an aged appearance with sagging jowls (bloodhound appearance) (Fig. 651-8), a hooked nose with everted nostrils, a short columella, a long upper lip, and everted lower eyelids. The skin is also lax elsewhere on the body and may resemble an ill-fitting suit. Hyperelasticity and hypermobility of the joints are not present as they are in the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Many infants have a hoarse cry, probably as a result of laxity of the vocal cords. Tensile strength of the skin is normal.

The dominant form of cutis laxa may develop at any age and is generally benign. When it manifests in infancy, it may be associated with intrauterine growth restriction, ligamentous laxity, and delayed closure of the fontanels. Pulmonary emphysema and mild cardiovascular manifestations may also occur. Patients with the more common recessive form of the disease are susceptible to severe complications, such as multiple hernias, rectal prolapse, diaphragmatic atony, diverticula of the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts, cor pulmonale, emphysema, pneumothoraces, peripheral pulmonary artery stenosis, and aortic dilatation. Characteristic facial features include downward-slanting palpebral fissures, a broad, flat nose, and large ears. Skeletal anomalies, dental caries, growth retardation, and developmental delay also occur. Such patients often have a shortened life span.

Cutis laxa–like skin changes may also be seen in association with multiple other syndromes, including De Barsy syndrome, Lenz-Majewski syndrome, hyperostotic dwarfism, SCARF (skeletal abnormalities, cutis laxa craniostenosis, ambiguous genitalia, retardation, facial abnormalities) syndrome, wrinkling skin syndrome, and Costello syndrome.

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) is a group of genetically heterogeneous connective tissue disorders. Affected children appear normal at birth, but skin hyperelasticity, fragility of the skin and blood vessels, delayed wound healing, and joint hypermobility (Fig. 651-9) develop. The essential defect is a quantitative deficiency of fibrillar collagen.

Classification

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome has been reclassified into 6 clinical forms.

Classic (Col5a1, Col5a2, Col1a1 Genes; Previously Eds Type I—Gravis, Eds Type II—Mitis)

This autosomal dominant disorder is characterized by premature birth caused by rupture of membranes, skin hyperelasticity and fragility, easy bruising, generalized and severe joint hypermobility, scoliosis, and mitral valve prolapse. Insignificant lacerations may form gaping wounds that leave broad, atrophic, papyraceous scars. Additional cutaneous manifestations include molluscoid pseudotumors over pressure points from accumulations of connective tissue. Life expectancy is not reduced.

Hypermobile (Col3a1 Gene; Previously Eds Type III)

This disorder has autosomal dominant inheritance and manifests as generalized severe joint hypermobility and minimal skin manifestations. Musculoskeletal pain is common, and osteoarthritis may develop prematurely.

Vascular (Col3a1 Gene; Previously Eds Type IV—Arterial Ecchymotic)

This autosomal dominant disorder shows the most pronounced dermal thinning of all. Consequently, the underlying venous network is prominent. The skin has minimal hyperextensibility, and the joints are not hypermobile, except perhaps during childhood. Premature birth, extensive ecchymoses from trauma, a high incidence of keloids, rupture of the bowel (especially the colon), uterine rupture during pregnancy, rupture of the great vessels, dissecting aortic aneurysm, and stroke all contribute to the increased morbidity and shortened life span. Patients should be advised to avoid becoming pregnant, avoid activities that raise intracranial pressure as a result of a Valsalva maneuver, such as trumpet playing, and minimize trauma to the skin. Celiprolol, a β1 antagonist and a β2 agonist (vasodilates), may reduce vascular events.

Kyphoscoliosis (Lysyl Hydroxylase [Plod Gene] Deficiency; Previously Eds Type VI)

Patients with this autosomal recessive type have joint hyperextensibility, hypotonia, kyphoscoliosis, fragile cornea, keratoconus, skin hyperelasticity, and fragile bones. Prenatal diagnosis is available through measurement of lysyl hydroxylase activity in amniocytes. The diagnosis can also be confirmed by detection of decreased lysyl hydroxylase activity in cultured dermal fibroblasts.

Arthrochalasia (Cola1a Gene, Type A; Col1a2 Gene, Type B; Previously Eds Types VIIA and B—Arthrochalasis Multiplex Congenita)

The A type is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by short stature, marked joint hyperextensibility and dislocation, and moderate hyperelasticity and bruisability of skin. The B type is autosomal dominant and is characterized by skin hyperelasticity and marked joint hypermobility.

Dermatospraxis (Type 1 Collagen N-Peptidase; Previously Eds Type VIIC)

This autosomal recessive condition that includes premature rupture of membranes; delayed closure of fontanels; skin fragility and laxity; easy bruisability; growth retardation; short limbs; umbilical hernia; and characteristic facies with micrognathia, jowls, and prominent, puffy eyelids.

Differential Diagnosis

Ehlers-Danlos syndrome has been confused with cutis laxa, but the features of the two disorders differ considerably. The skin of patients with cutis laxa hangs in redundant folds, whereas the skin of those with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is hyperextensible and snaps back into place when stretched. Because of the marked skin fragility in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, minor trauma results in ecchymoses, bleeding, and poor healing with atrophic cigarette-paper scars, which are most prominent on the forehead and lower legs and over pressure points. Surgical procedures are fraught with risk; dehiscence of wounds is common.

Pseudoxanthoma Elasticum

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Pseudoxanthoma elasticum (PXE) is a primary disorder of elastic tissue. The overwhelming majority of cases are due to mutations in the ABCC6 gene. The primary abnormality seen in PXE is an accumulation of mineralized tissue in the skin, Bruch membrane in the retina, and vessel walls. Although other forms of PXE have been postulated, their existence is now debated.

Clinical Manifestations

Onset of skin manifestations often occurs during childhood, but the changes produced by early lesions are subtle and may not be recognized. The characteristic pebbly, “plucked chicken skin” cutaneous lesions are 1-2 mm, asymptomatic, yellow papules that are arranged in a linear or reticulated pattern or in confluent plaques. Preferred sites are the flexural neck (Fig. 651-10), axillary and inguinal folds, umbilicus, thighs, and antecubital and popliteal fossae. As the lesions become more pronounced, the skin acquires a velvety texture and droops in lax, inelastic folds. The face is usually spared. Mucous membrane lesions may involve the lips, buccal cavity, rectum, and vagina. There is involvement of the connective tissue of the media, and intima of blood vessels, Bruch membrane of the eye, and endocardium or pericardium may result in visual disturbances, angioid streaks in Bruch membrane, intermittent claudication, cerebral and coronary occlusion, hypertension, and hemorrhage from the gastrointestinal tract, uterus, or mucosal surfaces. Women with PXE have an increased risk of miscarriage in the 1st trimester. Arterial involvement generally manifests in adulthood, but claudication and angina have occurred in early childhood.

Pathology

Histopathologic examination shows fragmented, swollen, and clumped elastic fibers in the middle and lower third of the dermis. The fibers stain positively for calcium. Collagen in the vicinity of the altered elastic fibers is reduced in amount and is split into small fibers. Aberrant calcification of the elastic fibers of the internal elastic lamina of arteries in PXE leads to narrowing of vessel lumina.

Elastosis Perforans Serpiginosa

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Elastosis perforans serpiginosa (EPS) is characterized by the extrusion of altered elastic fibers through the epidermis. The primary abnormality is probably in the dermal elastin, which provokes a cellular response that ultimately leads to extrusion of the abnormal elastic tissue.

Clinical Manifestations

This is an unusual skin disorder in which 1- to 3-mm, firm, skin-colored, keratotic papules tend to cluster in arcuate and annular patterns on the posterolateral neck and limbs (Fig. 651-11) and, occasionally, on the face and trunk. Onset usually occurs in childhood or adolescence. A papule consists of a circumscribed area of epidermal hyperplasia that communicates with the underlying dermis by a narrow channel. There is a great increase in the amount and size of elastic fibers in the upper dermis, particularly in the dermal papillae. Approximately 30% occur in association with osteogenesis imperfecta, Marfan syndrome, pseudoxanthoma elasticum, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Rothmund-Thomson syndrome, scleroderma, acrogeria, and Down syndrome. EPS has also occurred in association with penicillamine therapy.

Histology

Histopathology reveals a hyperplastic epidermis with extrusion of abnormal elastic fibers and a lymphocytic superficial infiltrate.

Reactive Perforating Collagenosis

Etiology/Pathogenesis

The primary process in reactive perforating collagenosis (RPC) represents transepidermal elimination of altered collagen. A familial autosomal recessive form has been described.

Clinical Manifestations

RPC usually manifests in early childhood as small papules on the dorsal areas of the hands and forearms, elbows, knees, and, sometimes, face and trunk. Over a period of several weeks, the papules enlarge to 5-10 mm, become umbilicated, and develop keratotic plugs in their centers (Fig. 651-12). Individual lesions resolve spontaneously in 2-4 mo, leaving hypopigmented macules or scars. Lesions may recur in crops; may undergo a linear Koebner phenomenon; and may form in response to cold temperatures or superficial trauma such as abrasions, insect bites, and acne lesions.

Mucopolysaccharidoses (Chapter 82)

In several of the mucopolysaccharidoses, thick, rough, inelastic skin, particularly on the extremities, and generalized hirsutism are characteristic but nonspecific features. Telangiectasias on the face, forearms, trunk, and legs have been observed in Scheie and Morquio syndromes. In some patients with Hunter syndrome, ivory-colored, distinctive firm papulonodules with a corrugated surface texture are grouped into symmetric plaques on the upper trunk (Fig. 651-13), arms, and thighs. Onset of these unusual lesions occurs in the 1st decade of life, and spontaneous disappearance has been noted.

Mastocytosis

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Mastocytosis encompasses a spectrum of disorders that range from solitary cutaneous nodules to diffuse infiltration of skin associated with involvement of other organs (Table 651-1). All of the disorders are characterized by aggregates of mast cells in the dermis. There are 4 types of mastocytoses: solitary mastocytoma; urticaria pigmentosa (2 forms); diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis; and telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans. The 2 forms of urticaria pigmentosa are the childhood variant, which resolves without sequelae, and the form that may start in either childhood or adult life and is associated with a mutation (most commonly the D816V mutation) in the stem cell factor gene. Stem cell factor (mast cell growth factor), which can be secreted by keratinocytes, stimulates the proliferation of mast cells and increases the production of melanin by melanocytes. The local and systemic manifestations of the disease are due, at least in part, to release of histamine and heparin from mast cell granules; although heparin is present in significant amounts in mast cells, coagulation disturbances occur only rarely. The vasodilator prostaglandin D2 or its metabolite appears to exacerbate the flushing response. Serum tryptase values are often elevated.

Table 651-1 MASTOCYTOSIS CLASSIFICATION*

* Classification adopted from World Health Organization classification.

Adapted from Carter MC, Metcalfe DD: Paediatric mastocytosis, Arch Dis Child 86:315-319, 2002.

Clinical Manifestations

Solitary mastocytomas are 1-5 cm in diameter. Lesions may be present at birth or may arise in early infancy at any site. The lesions may manifest as recurrent, evanescent wheals or bullae; in time, an infiltrated, pink, yellow, or tan, rubbery plaque develops at the site of whealing or blistering (Fig. 651-14). The surface acquires a pebbly, orange peel–like texture, and hyperpigmentation may become prominent. Stroking or trauma to the nodule may lead to urtication (Darier sign) as a result of local histamine release; rarely, systemic signs of histamine release become apparent.

Urticaria pigmentosa is the most common form of mastocytosis. In the first type of urticaria pigmentosa, the classic infantile type, lesions may be present at birth but more often erupt in crops in the first several months to 2 yr of age. New lesions seldom arise after age 3-4 yr. In some cases, early bullous or urticarial lesions fade, only to recur at the same site, ultimately becoming fixed and hyperpigmented. In others, the initial lesions are hyperpigmented. Vesiculation usually abates by 2 yr of age. Individual lesions range in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters and may be macular, papular, or nodular. They range in color from yellow-tan to chocolate brown and often have ill-defined borders (Fig. 651-15). Larger nodular lesions, like mastocytomas, may have a characteristic orange peel texture. Lesions of urticaria pigmentosa may be sparse or numerous and are often symmetrically distributed. Palms, soles, and face are sometimes spared, as are the mucous membranes. The rapid appearance of erythema and whealing in response to vigorous stroking of a lesion can usually be elicited; dermographism of intervening normal skin is also common. Affected children can have intense pruritus. Systemic signs of histamine release, such as hypotension, syncope, headache, episodic flushing, tachycardia, wheezing, colic, and diarrhea, occur most frequently in the more severe types of mastocytosis. Flushing is by far the most common symptom seen.

The second type of urticaria pigmentosa may begin any time from infancy to adulthood. This type does not resolve, and new lesions continue to develop throughout life. It is associated with mutations in the stem cell factor gene. Patients with this type of mastocytosis are the population in whom systemic involvement may develop. The only way to tell whether urticaria pigmentosa in a child will progress to the adult form is to identify the mutated form of stem cell factor.

Systemic mastocytosis is marked by an abnormal increase in the number of mast cells in other than cutaneous tissues. It occurs in approximately 5-10% of patients with mutant stem cell factor–related mastocytosis and is more common in adults than in children. Bone lesions may be silent but are detectable radiologically as osteoporotic or osteosclerotic areas, principally in the axial skeleton. Gastrointestinal tract involvement may produce complaints of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, steatorrhea, and bloating. Mucosal infiltrates may be detectable by barium studies or by small bowel biopsy. Peptic ulcers also occur. Hepatosplenomegaly as a result of mast cell infiltrates and fibrosis has been described, as has mast cell proliferation in lymph nodes, kidneys, periadrenal fat, and bone marrow. Abnormalities in the peripheral blood, such as anemia, leukocytosis, and eosinophilia, are noted in approximately 30% of patients. Mast cell leukemia may occur.

Diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis is characterized by diffuse involvement of the skin rather than discrete hyperpigmented lesions. Affected patients are usually normal at birth and demonstrate features of the disorder after the first few months of life. Rarely, the condition may present with intense generalized pruritus in the absence of visible skin changes. The skin usually appears thickened and pink to yellow and may have a doughy feel and a texture resembling an orange peel. Surface changes are accentuated in flexural areas. Recurrent bullae (Fig. 651-16), intractable pruritus, and flushing attacks are common, as is systemic involvement.

Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans is another variant that consists of telangiectatic hyperpigmented macules that are usually localized to the trunk. These lesions do not urticate when stroked. This form of the disease is seen primarily in adolescents and adults.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of solitary mastocytomas includes recurrent bullous impetigo, herpes simplex, congenital melanocytic nevi, and juvenile xanthogranuloma.

Urticaria pigmentosa can be confused with drug eruptions, postinflammatory pigmentary change, juvenile xanthogranuloma, pigmented nevi, ephelides, xanthomas, chronic urticaria, insect bites, and bullous impetigo.

Diffuse cutaneous mastocytoma may be confused with epidermolytic hyperkeratosis.

Telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans must be differential from other causes of telangiectasia.

Prognosis

Spontaneous involution occurs in all patients with solitary mastocytomas and classic infantile urticaria pigmentosa. The incidence of systemic manifestations in these patients is very low. The continued development of lesions past the age of 4 yr implies likely chronic disease with stem cell factor gene mutation and a higher risk for systemic involvement.

Treatment

Solitary mastocytomas usually do not require treatment. Lesions that blister may be treated with a 2-wk course of a superpotent topical steroid following each blistering episode.

In urticaria pigmentosa, flushing can be precipitated by excessively hot baths, vigorous rubbing of the skin, and certain drugs, such as codeine, aspirin, morphine, atropine, ketorolac, alcohol, tubocurarine, iodine-containing radiographic dyes, and polymyxin B (Table 651-2). Avoidance of these triggering factors is advisable; it is notable that general anesthesia may be safely performed with appropriate precautions.

Table 651-2 PHARMACOLOGIC AGENTS AND PHYSICAL STIMULI THAT MAY EXACERBATE MAST CELL MEDIATOR RELEASE IN PATIENTS WITH MASTOCYTOSIS

IMMUNOLOGIC STIMULI

Venoms (immunoglobulin E–mediated bee venom)

Complement-derived anaphylatoxins

Biologic peptides (substance P, somatostatin)

Polymers (dextran)

NONIMMUNOLOGIC STIMULI

Physical stimuli (extreme temperature, friction, sunlight)

Drugs

Acetylsalicylic acid and related nonsteroidal analgesics*

Thiamine

Ketorolac tromethamine

Alcohol

Narcotics (codeine, morphine)*

Radiographic dyes (iodine containing)

* Appears to be a problem in <10% of patients.

From Carter MC, Metcalfe DD: Paediatric mastocytosis, Arch Dis Child 86:315-319, 2002.

For patients who are symptomatic, oral antihistamines may be palliative. H1 receptor antagonists (hydroxyzine) are the initial drugs of choice for systemic signs of histamine release. If H1 antagonists are unsuccessful, H2 receptor antagonists may be helpful in controlling pruritus or gastric hypersecretion. Superpotent topical steroids are of benefit in controlling skin urtication and blistering. Oral mast cell–stabilizing agents, such as cromolyn sodium or ketotifen, may also be effective for diarrhea or abdominal cramping and some systemic symptoms such as headache or muscle pain.

For patients with diffuse cutaneous mastocytosis, the treatment is the same as for urticaria pigmentosa, although in early life. Phototherapy with narrow-band ultraviolet (UVB or UVA-1) or psoralen with UVA (PUVA) treatment may be required to control symptoms.

Lesions of telangiectasia macularis eruptiva perstans may be cautiously treated with vascular pulsed dye lasers.

Ahmad N, Evans P, Lloyd-Thomas AB. Anesthesia in children with mastocytosis—a case based review. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19:97-107.

Beers WH, Once A, Moore TL. Scleredema adultorum of Buschke: a case report and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2006;35:355-359.

Bergen AA, Plomp AS, Hu X, et al. ABCC6 and pseudoxanthoma elasticum. Pflugers Arch. 2007;453:685-691.

Brooke BS. Celiprolol therapy for vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Lancet. 2010;376:1443-1444.

Chan I, Liu L, Hamida T, et al. The molecular basis of lipoid proteinosis: mutations in extracellular matrix protein 1. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:881-890.

Christen-Zaech S, Hakim MD, Afsar FS, et al. Pediatric morphea (localized scleroderma): review of 136 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:385-396.

Cyr PR. Diagnosis and management of granuloma annulare. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1729-1734.

Hodak E, David M. Primary anetoderma and antiphospholipid antibodies—review of the literature. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2007;32:162-166.

Lee JK, Whittaker SJ, Enns RA, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations of systemic mastocytosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:7005-7008.

Martin L, Maitre F, Bonicel P, et al. Heterozygosity for a single mutation in the ABCC6 gene may closely mimic PXE. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:301-306.

Metcalfe DD. Mast cells and mastocytosis. Blood. 2008;112:946-956.

Ong KT, Perdu J, De Backer J, et al. Effect of celiprolol on prevention of cardiovascular events in vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome: a prospective randomised, open, blind-endpoints trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1476-1484.

Parapia LA, Jackson C. Ehlers-Danlos syndrome—a historical review. Br J Haematol. 2008;141:32-35.

Schoepe S, Schake H, May E, et al. Glucocorticoid therapy-induced skin atrophy. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:406-420.

Vearrier D, Buka RL, Roberts B, et al. What is the standard of care in the evaluation of elastosis perforans serpiginosa? A survey of pediatric dermatologists. Pediatr Dermatol. 2006;23:219-224.

Wolfram D, Tzankov A, Pulzl P, et al. Hypertrophic scars and keloids—a review of their pathophysiology, risk factors, and therapeutic management. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:171-181.