Chapter 654 Disorders of Hair

Disorders of hair in infants and children may be due to intrinsic disturbances of hair growth, underlying biochemical or metabolic defects, inflammatory dermatoses, or structural anomalies of the hair shaft. Excessive and abnormal hair growth is referred to as hypertrichosis or hirsutism. Hypertrichosis is excessive hair growth at inappropriate locations; hirsutism is an androgen-dependent male pattern of hair growth in women. Hypotrichosis is deficient hair growth. Hair loss, partial or complete, is called alopecia. Alopecia may be classified as nonscarring or scarring; the latter type is rare in children and, if present, is most often due to prolonged or untreated inflammatory conditions such as pyoderma and tinea capitis.

Hypertrichosis

Hypertrichosis is rare in children and may be localized or generalized and permanent or transient. Hypertrichosis has many causes, some of which are listed in Table 654-1.

Table 654-1 CAUSES OF AND CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH HYPERTRICHOSIS

INTRINSIC FACTORS

Racial and familial forms such as hairy ears, hairy elbows, intraphalangeal hair, or generalized hirsutism

EXTRINSIC FACTORS

Local trauma

Malnutrition

Anorexia nervosa

Long-standing inflammatory dermatoses

Drugs: Diazoxide, phenytoin, corticosteroids, Cortisporin, cyclosporine, androgens, anabolic agents, hexachlorobenzene, minoxidil, psoralens, penicillamine, streptomycin

HAMARTOMAS OR NEVI

Congenital pigmented nevocytic nevus, hair follicle nevus, Becker nevus, congenital smooth muscle hamartoma, fawn-tail nevus associated with diastematomyelia

ENDOCRINE DISORDERS

Virilizing ovarian tumors, Cushing syndrome, acromegaly, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, adrenal tumors, gonadal dysgenesis, male pseudohermaphroditism, non–endocrine hormone–secreting tumors, polycystic ovary syndrome

CONGENITAL AND GENETIC DISORDERS

Hypertrichosis lanuginosa, mucopolysaccharidosis, leprechaunism, congenital generalized lipodystrophy, de Lange syndrome, trisomy 18, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, Bloom syndrome, congenital hemihypertrophy, gingival fibromatosis with hypertrichosis, Winchester syndrome, lipoatrophic diabetes (Lawrence-Seip syndrome), fetal hydantoin syndrome, fetal alcohol syndrome, congenital erythropoietic or variegate porphyria (sun-exposed areas), porphyria cutanea tarda (sun-exposed areas), Cowden syndrome, Seckel syndrome, Gorlin syndrome, partial trisomy 3q, Ambra syndrome

Hypotrichosis and Alopecia

Some of the disorders associated with hypotrichosis and alopecia are listed in Table 654-2. True alopecia is rarely congenital; it is more often related to an inflammatory dermatosis, mechanical factors, drug ingestion, infection, endocrinopathy, nutritional disturbance, or disturbance of the hair cycle. Any inflammatory condition of the scalp, such as atopic dermatitis or seborrheic dermatitis, if severe enough, may result in partial alopecia; hair growth returns to normal if the underlying condition is treated successfully, unless the hair follicle has been permanently damaged.

Table 654-2 DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH ALOPECIA AND HYPOTRICHOSIS

Hair loss in childhood should be divided into the following 4 categories: congenital diffuse, congenital localized, acquired diffuse, and acquired localized.

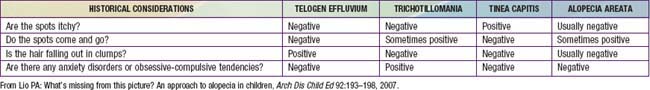

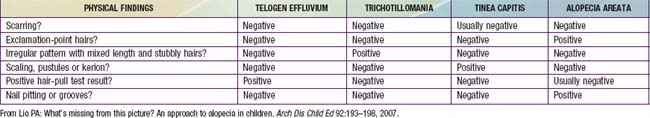

Acquired localized hair loss is the most common type of hair loss seen in childhood. Three conditions—traumatic alopecia, alopecia areata, tinea capitis—are predominantly seen (Tables 654-3 and 654-4).

Traumatic Alopecia (Traction Alopecia, Hair Pulling, Trichotillomania)

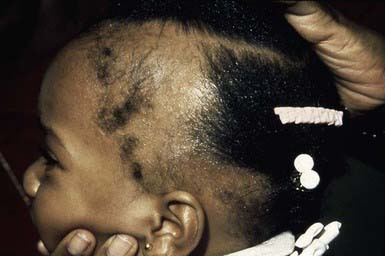

Traction Alopecia

Traction alopecia is common and is seen in almost 20% of African American schoolgirls. It is due to trauma to hair follicles from tight braids or ponytails, headbands, rubber bands, curlers, or rollers (Fig. 654-1). There is a greater risk of traction alopecia if hair trauma is combined with chemically relaxed hair. Broken hairs and inflammatory follicular papules in circumscribed patches at the scalp margins are characteristic and may be subtended by regional lymphadenopathy. Children and parents must be encouraged to avoid devices that cause trauma to the hair and, if necessary, to alter the hairstyle. Otherwise, scarring of hair follicles may occur.

Hair Pulling

Hair pulling in childhood is usually an acute reactional process related to emotional stress. It may also be seen in trichotillomania and as part of more severe psychiatric disorders.

Trichotillomania

Etiology/Pathogenesis

The diagnostic criteria for trichotillomania include visible hair loss attributable to pulling; mounting tension preceding hair pulling; gratification or release of tension after hair pulling; and absence of hair pulling attributable to hallucinations, delusions, or an inflammatory skin condition.

Clinical Manifestations

Compulsive pulling, twisting, and breaking of hair produces irregular areas of incomplete hair loss, most often on the crown and in the occipital and parietal areas of the scalp. Occasionally, eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair are traumatized. Some plaques of alopecia may have a linear outline. The hairs remaining within the areas of loss are of various lengths (Fig. 654-2) and are typically blunt-tipped because of breakage. The scalp usually appears normal, although hemorrhage, crusting (Fig. 654-3), and chronic folliculitis may also occur. Trichophagy, resulting in trichobezoars, may complicate this disorder.

Differential Diagnosis

Acute reactional hair pulling, tinea capitis, and alopecia areata must be considered in the differential diagnosis of trichotillomania (see Tables 654-3 and 654-4).

Histology

Histologic changes include coexistent normal and damaged follicles, perifollicular hemorrhage, atrophy of some follicles, and catagen transformation of hair. In late stages, perifollicular fibrosis may occur. Long-term repeated trauma may result in irreversible damage and permanent alopecia.

Treatment

Trichotillomania is closely related to obsessive-compulsive disorder and may be an expression of it for some children. When trichotillomania occur secondary to obsessive-compulsive disorder, clomipramine 50-150 mg/day or fluoxetine 40-80 mg/day may be helpful, particularly when combined with behavioral interventions (Chapter 22). N-Acetylcysteine may also be helpful.

Alopecia Areata

Etiology/Pathogenesis

Alopecia areata is an immune-mediated nonscarring alopecia. The cause is unknown. It is hypothesized that in genetically susceptible individuals, loss of immune privilege of the hair follicle allows for T-cell inflammation against anagen hairs follicles, leading to stoppage of hair growth.

Clinical Manifestations

Alopecia areata is characterized by rapid and complete loss of hair in round or oval patches on the scalp (Fig. 654-4) and on other body sites. In alopecia totalis, all the scalp hair is lost (Fig. 654-5); alopecia universalis involves all body and scalp hair. The lifetime incidence of alopecia areata is 0.1% to 0.2% of the population. More than half of affected patients are younger than 20 yr.

The skin within the plaques of hair loss appears normal. Alopecia areata is associated with atopy and with nail changes such as pits (Fig. 654-6), longitudinal striations, and leukonychia. Autoimmune diseases such as Hashimoto thyroiditis, Addison disease, pernicious anemia, ulcerative colitis, myasthenia gravis, collagen vascular diseases, and vitiligo may also be seen. An increased incidence of alopecia areata has been reported in patients with Down syndrome (5-10%).

Differential Diagnosis

Tinea capitis, seborrheic dermatitis, trichotillomania, traumatic alopecia, and lupus erythematosus should be considered in the differential diagnosis of alopecia areata (see Tables 654-3 and 654-4).

Histology

A perifollicular infiltrate of inflammatory round cells is found in biopsy specimens from active areas of alopecia areata.

Treatment

The course is unpredictable, but spontaneous resolution in 6-12 mo is usual, particularly when relatively small, stable patches of alopecia are present. Recurrences are common. Onset at a young age, extensive or prolonged hair loss, and numerous episodes are usually poor prognostic signs. Alopecia universalis, alopecia totalis, and alopecia ophiasis (Fig. 654-7)—a type of alopecia areata in which hair loss is circumferential—are also less likely to resolve. Therapy is difficult to evaluate because the course is erratic and unpredictable. The use of high- or super-potency topical corticosteroids is effective in some patients. Intradermal injections of steroid (triamcinolone 5 mg/mL) every 4-6 wk may also stimulate hair growth locally, but this mode of treatment is impractical in young children or in patients with extensive hair loss. Systemic corticosteroid therapy (prednisone 1 mg/kg/day) has been associated with good results; the permanence of cure is questionable, however, and the side effects of chronic oral corticosteroids are a serious deterrent. Additional therapies that are sometimes effective include short-contact anthralin, topical minoxidil, and contact sensitization with squaric acid dibutylester or diphencyprone. In general, parents and patients can be reassured that spontaneous remission of alopecia areata usually occurs. New hair growth may initially be of finer caliber and lighter color, but replacement by normal terminal hair can be expected.

Acquired Diffuse Hair Loss

Telogen Effluvium

Telogen effluvium manifests as sudden loss of large amounts of hair, often with brushing, combing, and washing of hair. Diffuse loss of scalp hair occurs from premature conversion of growing, or anagen, hairs, which normally constitute 80-90% of hairs, to resting, or telogen, hairs. Hair loss is noted 6 wk-3 mo after the precipitating cause, which may include childbirth; a febrile episode; surgery; acute blood loss, including blood donation; sudden severe weight loss; discontinuation of high-dose corticosteroids or oral contraceptives; and psychiatric stress. Telogen effluvium also accounts for the loss of hair by infants in the first few months of life; friction from bed sheets, particularly in infants with pruritic, atopic skin, may exacerbate the problem. There is no inflammatory reaction; the hair follicles remain intact, and telogen bulbs can be demonstrated microscopically on shed hairs. Because >50% of the scalp hair is rarely involved, alopecia is usually not severe. Parents should be reassured that normal hair growth will return within approximately 3-6 mo.

Toxic Alopecia (Anagen Effluvium)

Anagen effluvium is an acute, severe, diffuse inhibition of growth of anagen follicles, resulting in loss of >80-90% of scalp hair. Hairs become dystrophic, and the hair shaft breaks at the narrowed segment. Loss is diffuse, rapid (1-3 wk after treatment), and temporary, as regrowth occurs after the offending agent is discontinued. Causes of anagen effluvium include radiation; cancer chemotherapeutic agents such as antimetabolites, alkylating agents, and mitotic inhibitors; thallium; thiouracil; heparin; the coumarins; boric acid; and hypervitaminosis A.

Congenital Diffuse Hair Loss

Congenital diffuse hair loss is defined as congenitally thin hair diffusely related to either hypoplasia of hair follicles or to structural defects in hair shafts.

Structural Defects of Hair

Structural defects of the hair shaft may be congenital, reflect known biochemical aberrations, or relate to damaging grooming practices. All the defects can be demonstrated by microscopic examination of affected hairs, particularly with scanning and transmission electron microscopy.

Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Congenital trichorrhexis nodosa is an autosomal dominant condition. The hair is dry, brittle, and lusterless, with irregularly spaced grayish white nodes on the hair shaft. Microscopically, the nodes have the appearance of two interlocking brushes (Fig. 654-8A). The defect results from a fracture of the hair shaft at the nodal points caused by disruption of the cells in the hair cortex. Trichorrhexis nodosa has also been observed in some infants with Menkes syndrome, trichothiodystrophy, citrullinemia, and argininosuccinic aciduria.

Figure 654-8 A, Microscopic hair fracture in trichorrhexis nodosa. B, Beading of hair in monilethrix. C, Cuplike abnormality of hair in Netherton syndrome.

Acquired Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Acquired trichorrhexis nodosa, the most common cause of hair breakage, occurs in two forms. Proximal defects are found most frequently in African-American children, whose complaint is not of alopecia but of failure of the hair to grow. The hair is short, and longitudinal splits, knots, and whitish nodules can be demonstrated in hair mounts. Easy breakage is demonstrated by gentle traction on the hair shafts. A history of other affected family members may be obtained. The problem may be caused by a combination of genetic predisposition and the cumulative mechanical trauma of rough combing and brushing, hair-straightening procedures, and “permanents.” Patients must be cautioned to avoid damaging grooming techniques. A soft natural-bristle brush and a wide-toothed comb should be used. The condition is self-limited, with resolution in 2-4 yr if patients avoid damaging practices. Distal trichorrhexis nodosa is seen more frequently in white and Asian children. The distal portion of the hair shaft is thinned, ragged, and faded; white specks, sometimes mistaken for nits, may be noted along the shaft. Hair mounts reveal the paintbrush defect and the sites of excessive fragility and breakage. Localized areas of the moustache or beard may also be affected. Avoidance of traumatic grooming, regular trimming of affected ends, and the use of cream rinses to lessen tangling ameliorate this condition.

Pili Torti

Patients with pili torti present with spangled, brittle, coarse hair of different lengths over the entire scalp. There is a structural defect in which the hair shaft is grooved and flattened at irregular intervals and is twisted on its axis to various degrees. Minor twists that occur in normal hair should not be misconstrued as pili torti. Curvature of the hair follicle apparently leads to the flattening and rotation of the hair shaft. The genetic defect in isolated pili torti is unknown, and both autosomal dominant and recessive forms have been described. Syndromes in which the hair shaft abnormalities of pili torti are seen in association with other cutaneous and systemic abnormalities include Menkes kinky hair syndrome, Björnstad syndrome (pili torti with deafness; BCS1L gene), and multiple ectodermal dysplasia syndromes.

Menkes Kinky Hair Syndrome (Trichopoliodystrophy)

Males with Menkes kinky hair syndrome, an X-linked recessive trait, are born to an unaffected mother after a normal pregnancy. Neonatal problems include hypothermia, hypotonia, poor feeding, seizures, and failure to thrive. Hair is normal to sparse at birth but is replaced by short, fine, brittle, light-colored hair that may have features of trichorrhexis nodosa, pili torti, or monilethrix. The skin is hypopigmented and thin, cheeks typically appear plump, and the nasal bridge is depressed. Progressive psychomotor retardation is noted in early infancy. Mutations in the ATP7A gene, encoding a copper-transporting adenosine triphosphatase protein, cause Menkes kinky hair syndrome. It is due to maldistribution of the copper in the body. Copper uptake across the brush border of the small intestine is increased, but copper transport from these cells into the plasma is defective, resulting in low total body copper stores. Parenteral administration of copper-histidine is helpful if begun in the first 2 mo of life.

Monilethrix

The hair shaft defect known as monilethrix is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with variable age of onset, severity, and course. Mutations in the hair keratins HBI, HB3, and HB6 have been identified. The hair appears dry, lusterless, and brittle, and it fractures spontaneously or with mild trauma. Eyebrows, lashes, body and pubic hair, and scalp hair may be affected. Monilethrix may be present at birth, but the hair is usually normal at birth and is replaced in the first few months of life by abnormal hairs; the condition is sometimes first apparent in childhood. Follicular papules may appear on the nape of the neck and the occiput and, occasionally, over the entire scalp. Short, fragile beaded hairs that emerge from the horny follicular plugs give a distinctive appearance. Keratosis pilaris and koilonychia of fingernails and toenails may also be present. Microscopically, a distinctive, regular beading pattern of the hair shaft is evident, characterized by elliptic nodes that are separated by narrower internodes (Fig. 654-8B). Not all hairs have nodes, and both normal and beaded hairs may break. Patients should be advised to handle the hair gently to minimize breakage. Treatment is generally ineffective.

Trichothiodystrophy

Hair in trichothiodystrophy is sparse, short, brittle, and uneven; the scalp hair, eyebrows, or eyelashes may be affected. Microscopically, the hair is flattened, folded, and variable in diameter; has longitudinal grooving; and has nodal swellings that resemble those seen in trichorrhexis nodosa. Under a polarizing microscope, distinctive alternating dark and light bands are seen. The abnormal hair has a cystine content that is <50% of normal because of a major reduction in and altered composition of constituent high-sulfur matrix proteins. Trichothiodystrophy may occur as an isolated finding or in association with various syndrome complexes that include intellectual impairment, short stature, ichthyosis, nail dystrophy, dental caries, cataracts, decreased fertility, neurologic abnormalities, bony abnormalities, and immunodeficiency (TTDN1 gene). Some patients are photosensitive and have impairment of DNA repair mechanisms, similar to that seen in groups B and D xeroderma pigmentosum; the incidence of skin cancers, however, is not increased. Patients with trichothiodystrophy tend to resemble one another, with a receding chin, protruding ears, raspy voice, and sociable, outgoing personality. Trichoschisis, a fracture perpendicular to the hair shaft, is characteristic of the many syndromes that are associated with trichothiodystrophy. Perpendicular breakage of the hair shaft has also been described in association with other hair abnormalities, particularly monilethrix.

Trichorrhexis Invaginata (Bamboo Hair)

Short, sparse, fragile hair without apparent growth is characteristic of trichorrhexis invaginata, which is found primarily in association with Netherton syndrome (Chapter 649). It has also been reported in other ichthyosiform dermatoses. The distal portion of the hair is invaginated into the cuplike proximal portion, forming a fragile nodal swelling (Fig. 654-8C).

Pili Annulati

Alternate light and dark bands of the hair shaft characterize pili annulati. When viewed under the light microscope, the region of the hair shaft that appeared bright in reflected light instead appears dark in the transmitted light as a result of focal aggregates of abnormal air-filled cavities within the shaft. The hair is not fragile. The defect may be autosomal dominant or sporadic in inheritance. Pseudopili annulati is a variant of normal blond hair; an optical effect caused by the refraction and reflection of light from the partially twisted and flattened shaft creates the impression of banding.

Woolly Hair Disease

Woolly hair diseases manifest at birth as peculiarly tight, curly, abnormal hair in a non-black person. Autosomal dominant and recessive (PKRY5 gene) types have been described. Woolly hair nevus, a sporadic form, involves only a circumscribed portion of the scalp hair. The affected hair is fine, tightly curled, and light colored, and it grows poorly. Microscopically, an affected hair is oval and shows twisting of 180 degrees on its axis.

Uncombable Hair Syndrome (Spun-Glass Hair)

The hair of patients with uncombable hair syndrome appears disorderly, is often silvery blond (Fig. 654-9), and may break because of repeated, futile efforts to control it. The condition is probably autosomal dominant in inheritance. Eyebrows and eyelashes are normal. A longitudinal depression along the hair shaft is a constant feature, and most hair follicles and shafts are triangular (pili trianguli et canaliculi). The shape of the hair varies along its length, however, preventing the hairs from lying flat.

Bedocs LA, Bruckner AL. Adolescent hair loss. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:431-435.

Cheng AS, Bayliss SJ. The genetics of hair shaft disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;59:1-22.

Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. N-Acetylcysteine, a glutamate modulator, in the treatment of trichotillomania. Arch Gen Psych. 2009;66(7):756-763.

Harries MJ, Sun J, Paus R, et al. Management of alopecia areata. BMJ. 2010;341:242-246.

Khumalo NP, Jessop S, Gumedze F, et al. Determinants of marginal traction alopecia in African girls and women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:432-438.

Lio PA. What’s missing from this picture? An approach to alopecia in children. Arch Dis Child Ed. 2007;92:193-198.

Sah DE, Koo J, Price VH. Trichotillomania. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:13-21.