chapter 13 Sexually Transmitted Infections

Screening and detecting sexually transmitted infections (STIs) is a form of secondary prevention that interrupts further transmission as well as progression of the infection and its sequelae. Unfortunately, primary prevention, by means of education and safe sex practices, has not been enough to significantly curb the prevalence and high cost of STIs.

People at high risk of contracting STIs are young adults between the ages of 18 and 28. It is also important to bear in mind that STIs rank among the top five risks of international travelers, along with diarrhea, hepatitis, and motor vehicle accidents (Mawhorter, 1997).

The brunt of the STI burden, both in risk and consequence, falls on women. When exposed to STIs, women are more likely to become infected and are much more likely to be asymptomatic. STIs can cause pelvic inflammatory disease, with subsequent risks of chronic pain syndromes, ectopic pregnancy, and infertility. Unfortunately there is very little evidence that treatment will reverse the sequelae.

A urologist should have a high index of suspicion for underlying STI in women who present with recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) and in those who are symptomatic with sterile urine cultures. Up to 50% of women with signs of UTI during emergency department examination had subsequent positive cultures for STI (Berg et al, 1996). Physicians should maintain the same level of vigilance when treating women who have sex with women. Genital human papillomavirus (HPV) has been identified along with squamous intraepithelial lesions among lesbians and occurs among those who have not had sexual relations with men (Marrazzo et al, 1998).

Proctitis may occur in women and men who have anal sex. Causative organisms include Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, Treponema pallidum, and herpes simplex virus (HSV). A discussion of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is beyond the scope of this chapter (see Chapter 14); however, it is important to remember that STIs—especially the ulcerative types—facilitate the transmission and infection of HIV. HSV type 2, in particular, may play a role in the transmission of HIV because it has been identified more frequently than other STIs among HIV-concordant couples. Increased risk of HIV concordance has also been observed among couples who both have Mycoplasma genitalium antibodies (Perez et al, 1998).

Evidence is available that has shown that the spermicide nonoxynol-9 is not preventive against STIs and that its frequent use may actually be detrimental by increasing the rate of genital ulceration and HIV transmission (Richardson, 2002).

It is imperative that the physician treating STIs make special efforts to be sure that his or her methods of diagnosis and treatment reflect the latest knowledge. To that end, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) periodically updates recommendations for STI treatment, which can be retrieved easily by checking the CDC website. Changes that occur in the interim will need to come from a review of current literature. The accurate diagnosis and treatment of a patient with an STI will allow the physician to treat not only the patient but also the sexual partner and possibly the couple’s unborn children.

The most common STIs are discussed in this chapter and include HSV infection, chlamydial urethritis/cervicitis, lymphogranuloma venereum, syphilis, gonorrhea, chancroid, trichomoniasis, HPV infection, and scabies. Other sexually associated pathogens, which cause urethritis and vaginitides, are also discussed briefly.

Epidemiology and Trends

It is estimated that more than 19 million new cases of STIs are reported each year and more than 65 million people are infected with incurable viral STIs (CDC, 2010b; American Social Health Association, 1998). Approximately two thirds of cases occur in adolescents and young adults. The most common STIs are HPV and HSV infections. Of the top 10 nationally notifiable infectious diseases in the United States in 2008, 4 were STIs (CDC, 2008). This does not include HPV and HSV infections because they are not reportable diseases.

The prevalence of infection with HPV in the United States is approximately 20 million, and the incidence is 6.2 million (Catea, 1999; Weinstock, 2004). At least 50% of sexually active men and women acquire genital HPV infection at some point in their lives. By age 50, at least 80% of women will have acquired genital HPV infection (STD Facts, 2005).

In 2009, only 28 cases of chancroid were reported, down from 67 cases in 2002 (CDC, 2010b). Interestingly, 71% were reported from the three states of Tennessee, Wisconsin, and Texas. Overall, the rate of reported cases has declined 99% since 1987. Haemophilus ducreyi is difficult to culture, and therefore the infection could be underdiagnosed. Improved diagnostic testing by means of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is now commercially available and may increase diagnostic capability.

The incidence of infection with Chlamydia has continued to rise since it became a notifiable disease in 1995. In 2009, over 1.2 million cases were reported to the CDC (CDC, 2010b). The reported number of cases of chlamydial infection was about four times greater than the reported cases of gonorrhea. It is probable that this incidence is at least in part secondary to improved diagnostic ability and growth and implementation of routine screening programs in women. Now that highly sensitive nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) for urine are available, the diagnosis of chlamydial infection is increasing in both symptomatic and asymptomatic men. From 2005 to 2009, the rate of chlamydial infection among men increased 37.6% compared with 20.3% among women.

The rate of gonorrhea was fairly stable from 1996-2006 at approximately 115 cases per 100,000 population, and then decreased from 2006-2009 to a rate of approximately 99.1 per 100,000 population in 2009 (CDC, 2009). The incidence rate is highest in persons aged 15 to 24 and is particularly high for non-Hispanic blacks (20 times higher than for non-Hispanic whites). Rates are particularly higher for non-Hispanic blacks (which is 20 times the rate for non-Hispanic whites) and for men who have sex with men (Fox et al, 2001; CDC, 2010b). There has also been a significant increase in quinolone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae, such that fluoroquinolones are no longer recommended for treatment in the United States (CDC, 2007).

The rate of syphilis increased yearly during 2001-2009, primarily among men (3.0 cases per 100,000 population in 2001 compared to 7.8 cases in 2009). The rate among women increased from 0.8 cases in 2004 to 1.4 cases in 2009 (CDC, 2010b). It has been proposed that this is secondary to outbreaks among males having sex with males in urban areas with high rates of coinfection with HIV and high-risk sexual behavior (CDC, 2004b). Rates continue to be particularly high in southern states and among African-Americans. There is no evidence that screening high-risk individuals, including those with HIV or other STIs, or the general population reduces morbidity or mortality from syphilis. However, it has been shown that screening pregnant women reduces the prevalence of congenital syphilis (Coles et al, 1998).

Expedited Partner Therapy

A common dilemma for physicians treating patients with an STI is how to expeditiously extend treatment to the partner to prevent complications from infection, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, and prevent the spread of disease. Expedited partner therapy (EPT) is the practice of treating the sexual partners of patients with STI by providing the patient with a prescription or medication to take to his or her partner without an intervening clinical evaluation or professional prevention counseling.

In the past, once an STI was reported to the health department the health department notified past and present sexual partners of the patient. However, the increased incidence of HIV and threats of bioterrorism are competing for health department resources and many departments now only notify partners of patients with HIV or syphilis (Erbelding and Zenilman, 2005). Patients are now requested to notify their own partners, who are then expected to go for evaluation and treatment themselves. The problems with this proposal are evident, and already this concept has been shown to be ineffective (Macke and Maher, 1999). Golden and colleagues (2003) reported their success implementing an expedited treatment plan for partners that did not require medical evaluation. This was a randomized controlled trial in which patients in the expedited treatment group were given a “partner packet” of therapy to deliver to the partner themselves or, if they were unwilling to do so, the partner was notified by the physician staff and the packet was delivered by mail or could be picked up at a participating pharmacy. Both the patients and partners in the expedited treatment group had better outcomes than the control group. Although this approach is sensible, effective, and progressive, legal and clinical barriers may unfortunately prevent the widespread acceptance of this approach.

In 2006 the CDC concluded that EPT has been shown to be at least equivalent to patient referral in preventing persistent or recurrent gonococcal or chlamydial infection in heterosexuals and released guidelines for the uses of EPT (CDC, 2006). The guidelines recommend that EPT should be implemented only when other management strategies are impractical or unsuccessful. All recipients should be encouraged to seek medical attention in addition to accepting therapy by EPT, through counseling of the index case, written materials, and/or personal counseling by a pharmacist or other personnel. However, EPT should not be used routinely in men who have sex with men because of a lack of data to confirm efficacy in this population and the high risk of comorbidity, especially with undiagnosed HIV. Similarly, EPT should not be used for partners of women with trichomoniasis because of the high risk of comorbidity with chlamydial or gonococcal infection or in the management of patients with infectious syphilis.

The CDC collaborated with the Center for Law and the Public’s Health at Georgetown and Johns Hopkins Universities to assess the legal framework concerning EPT in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. The objective of the research was to conceptualize and identify legal provisions that implicate a clinician’s ability to execute EPT. As of January 2011, EPT is allowable in 27 states, potentially allowable in 15 states including the district of Columbia and Puerto Rico, and legally prohibited in 8 states. The results of the research, explanation, and up-to-date legal status for each state can be found at the CDC website (CDC, 2010; www.cdc.gov/std/ept/legal).

Genital Ulcers

Several sexually transmitted infections are clinically characterized by genital ulcers and most commonly include HSV infection or syphilis. Other STIs that may manifest with ulcer include chanchroid and granuloma inguinale.

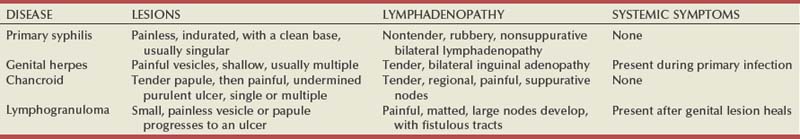

Although specificity for clinical diagnosis of genital ulcer disease is good (94% to 98%), sensitivity is quite low (31% to 35%) (DiCarlo and Martin, 1997). Inguinal lymph node findings did not contribute to diagnostic accuracy. Patients with genital, perianal, or anal ulcers should undergo a diagnostic evaluation for HSV and serologic testing for syphilis. Testing for Haemophilus ducreyi should be conducted in areas where chancroid is prevalent. Specifically, the CDC recommends (1) serology and either darkfield examination or direct immunofluorescence for Treponema pallidum, (2) culture or PCR test for HSV, and (3) serologic testing for type-specific HSV antibody (CDC, 2010c). One should bear in mind that patients may have more than one STI. Approximately 10% of patients with chancroid also have HSV infection or syphilis. HIV testing should also be considered in the management of patients with confirmed STI. Clinical characteristics of sexually transmitted genital ulcers are summarized in Table 13–1. Other causes that are not sexually transmitted, such as Behçet syndrome, drug reaction, erythema multiforme, Crohn disease, lichen planus, amebiasis, trauma, and carcinoma, must also be considered. Empirical treatment for the most likely cause based on history and physical examination should be initiated as laboratory test results are pending. If ulcers do not respond to therapy or appear unusual, a biopsy should be performed.

Herpes Simplex Virus Infection

Diagnosis

Genital herpes infection is common, afflicting more than 50 million people in the United States (Xu et al, 2006). It is caused by HSV type 2 (HSV-2) in 85% to 90% of cases and HSV type 1 (HSV-1) in 10% to 15% of cases. HSV-1 is responsible for common cold sores but can be transmitted via oral secretions during oral-genital sex. Silent infection is common and may account for more than 75% of viral transmission (Langenberg et al, 1999). Up to 80% of women with HSV-2 antibodies have no history of clinical infection (White and Wardropper, 1997). The incubation period ranges from 1 to 26 days but is usually short, approximately 4 days. Nongenital infection of HSV-1 during childhood may be protective to some extent against subsequent genital HSV-2 infection in adults. When exposed to HSV-2, women with negative HSV-1 antibodies had a 32% risk of infection per year whereas women with positive antibodies had a 10% risk of infection per year (Baker, 1997).

Primary infection manifests as painful ulcers of the genitalia or anus and bilateral painful inguinal adenopathy. The initial presentations for HSV-1 and HSV-2 are the same. A group of vesicles on an erythematous base that does not follow a neural distribution is pathognomonic (Figs. 11-1 to 11-3). The differential diagnosis includes other STIs, such as primary syphilis and chancroid, as well as noninfectious disorders such as Crohn disease, trauma, contact dermatitis, erythema multiforme, Reiter syndrome, psoriasis, and lichen planus.

The initial infection is often associated with constitutional flulike symptoms. Sacral radiculomyelopathy is a rare manifestation of primary infection that has a greater association with primary anal HSV. Genital lesions, especially urethral lesions, may cause transient urinary retention in women. Recurrent episodes are usually less severe, involving only ulceration of the genital or anal area. Severe disease and complications of herpes include pneumonitis, disseminated infection, hepatitis, meningitis, and encephalitis. Asymptomatic viral shedding can take place for up to 3 months after clinical presentation, thereby perpetuating the risk of transmission (Baker, 1997).

The diagnosis of genital herpes should not be made on clinical suspicion alone because the classic presentation of the ulcer occurs in only a small percentage of patients. Women especially may present with atypical lesions such as abrasions, fissures, or itching (ACOG Practice Bulletin, 2004). Viral culture with subtyping has been the gold standard of diagnosis of herpes infection. Viral subtype should be determined in every patient because it is important for prognosis and counseling. Women with HSV-2 have an average of four recurrences within the first year, and women with HSV-1 have one recurrence in the first year. After the first year, HSV-1 rarely recurs whereas the rate of HSV-2 decreases but slowly (Bendedetti et al, 1994). Viral culture can generally isolate the virus in 5 days, is relatively inexpensive, and is highly specific. However, the sensitivity of viral culture ranges from 30% to 95%, depending on the stage of the lesion and whether it is the primary infection or a recurrence. Viral load is highest when the lesion is vesicular and during primary infection. Therefore, viral culture has the highest sensitivity at these times and declines sharply as the lesion heals.

There are currently three U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved type-specific antibody assays (HerpeSelect HSV-1 and HSV-2 ELISA, HerpeSelect HSV-1 and HSV-2 Immunoblot, and Captia ELISA). These tests identify antibodies to HSV glycoproteins G-1 and G-2, which evoke a type-specific antibody response (Wald and Ashley-Morrow, 2002). These tests may also be able to identify recently acquired versus established HSV infection based on antibody avidity (Morrow et al, 2004).

Antigen detection kits are available but cannot distinguish reliably between HSV-1 and HSV-2. PCR testing has been shown to be 1.5 to 4 times as sensitive as viral culture. Samples are easy to attain and more stable than samples for viral culture. PCR testing will most likely replace viral culture as its availability increases and cost decreases.

Treatment

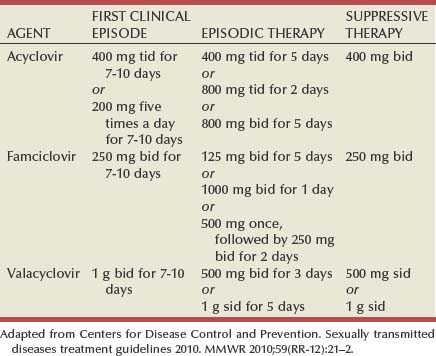

Antiviral therapies approved for treatment include those using oral acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir (Table 13–2). Topical antiviral medications are not effective. Recurrences can be treated with an episodic or suppressive approach. When used for episodic treatment, medication must be initiated during the prodrome or within 1 day of the onset of lesions. Daily suppressive therapy has been shown to prevent 80% of recurrences and is an option for patients who suffer from frequent recurrences. It has been shown to decrease the frequency and duration of recurrences as well as viral shedding and therefore reduce the rate of transmission. The safety and efficacy of daily suppressive therapy has been well documented.

Chancroid

Diagnosis

Chancroid, caused by Haemophilus ducreyi, is the most common ulcerative STI worldwide but is rare in the United States. It affects men three times more often than women. The incubation period ranges from 1 to 21 days. It causes a painful, nonindurated ulcer on the penis or vulvovaginal area. The ulcer has a friable base covered with a gray or yellow purulent exudate and a shaggy border. It can spread laterally by apposition to inner thighs and buttocks, especially in women. It is associated with inguinal adenopathy that is typically unilateral and tender with a tendency to become suppurative and fistulize (Figs. 13-4 and 13-5). H. ducreyi is fastidious and difficult to culture. The special culture media is not widely available, and sensitivity of culture remains less than 80%. Gram stain of a specimen obtained from the undermined edge of the ulcer may be more helpful in identifying the short, fine, gram-negative streptobacilli, which are usually arranged in short, parallel chains. Recently, PCR assays have been shown to be a sensitive and specific means of detecting H. ducreyi. Although no PCR test is currently FDA approved, testing can be performed by commercial agencies. HIV and syphilis screening should be performed at the time of diagnosis and 3 months after treatment if initial results are negative.

Treatment

Single-dose treatments consist of azithromycin, 1 g orally, or ceftriaxone, 250 mg intramuscularly. Alternative regimens include ciprofloxacin, 500 mg twice daily for 3 days, or erythromycin base, 500 mg by mouth three times daily for 7 days. However, antibiotic susceptibility varies geographically. Resistance has been reported to ciprofloxacin and erythromycin in some regions. Ciprofloxacin is contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation. Subjective improvement should be noted within 3 days, and ulcers generally heal completely in 7 to 14 days. Healing may be slower in uncircumcised men with ulcers below the foreskin and in patients with HIV (Schmid, 1999). Patients should be reexamined in 5 to 7 days. Sexual partners should be examined and treated if sexual relations were held within 2 weeks before or during the eruption of the ulcer. Symptomatic relief of inguinal tenderness can be provided by needle aspiration or incision and drainage of the buboes.

Syphilis

Diagnosis

Syphilis is caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Incubation periods range between 10 and 90 days. It is spread through contact with infectious lesions or body fluids. It can also be acquired in utero and through blood transfusion. Syphilis has been categorized into overlapping stages based on clinical signs and symptoms to guide diagnosis and treatment. Primary syphilis is characterized by a single painless, indurated ulcer occurring at the site of inoculation that appears about 3 weeks after inoculation and persists for 4 to 6 weeks (Figs. 13-6 and 13-7). The ulcer is typically found on the glans, corona, or perianal area on men and on the labial or anal area on women. It is often associated with bilateral, nontender inguinal or regional lymphadenopathy. Because the ulcer and adenopathy are painless and heal without treatment, primary syphilis often goes unnoticed.

Secondary syphilis usually begins 4 to 10 weeks after the appearance of the ulcer but may present as long as 24 months after the initial infection. Secondary syphilis manifests as mucocutaneous, constitutional, and parenchymal signs and symptoms (Figs. 13-8 and 13-9). Frequent early manifestations consist of maculopapular rash, which is commonly seen on the trunk and arms, and generalized nontender lymphadenopathy. After several days or weeks, a papular rash may accompany the primary rash. These papular lesions are associated with endarteritis and may therefore become necrotic and pustular. The distribution widens and commonly affects the palms and soles. In the intertriginous areas these papules may enlarge and erode to produce condyloma lata, which are particularly infectious. Less common manifestations of secondary syphilis include hepatitis and immune complex–induced glomerulonephritis (Goldmeier and Guallar, 2003).

Approximately one third of untreated patients will develop tertiary syphilis. It is very rare in industrialized countries, except for occasional cases reported in HIV patients. Syphilis is a systemic disease that can affect almost any organ or system, especially the cardiovascular, skeletal, and central nervous systems, and skin. Neurosyphilis can occur at any stage. Aortitis, meningitis, uveitis, optic neuritis, general paresis, tabes dorsalis, and gummas of the skin and skeleton are just some of the sequelae associated with tertiary syphilis.

Latent syphilis is defined as seroreactivity with no clinical evidence of disease. Early latent syphilis is latent syphilis acquired within the past year. All other latent syphilis is either referred to as late latent syphilis or latent syphilis of unknown duration.

Darkfield microscopy and direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) tests can be performed on specimens obtained from primary or secondary lesions. Darkfield microscopy is not widely available, but DFA testing of a fixed smear from a lesion can be performed at many commercial laboratories. Nontreponemal serologic testing with rapid plasma reagin (RPR) or Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) are the most common methods of screening suspected individuals. Sensitivity is 78% and 86% for RPR and VDRL, respectively, in primary syphilis, 100% for both in secondary syphilis, and over 95% in tertiary syphilis (Hart, 1986). The false-positive rate is 1% to 2% and may be secondary to a large variety of causes (Golden et al, 2003). Therefore, all positive tests should be confirmed with treponemal testing using T. pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA) or fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed (FTA-ABS) testing. HIV can cause false-negative results by both treponemal and nontreponemal methods (Hicks et al, 1987; Erbelding et al, 1997). Positive treponemal antibody tests usually remain positive for life and do not correlate with disease activity. Nontreponemal antibody titers, RPR and VDRL, correlate with disease activity. These tests usually become negative 1 year after treatment. A low percentage of patients remain “serofast,” never regaining a negative titer. A fourfold difference in titer is reflective of a clinically significant difference. A fourfold increase after therapy is indicative of ineffective therapy or reinfection (Johnson and Farnie, 1994). A fourfold decrease represents successful treatment. Following disease activity, the same test, either RPR or VDRL, should be performed at the same laboratory because the results are not interchangeable and may vary from laboratory to laboratory.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that pregnant women and people who are at higher risk for syphilis infection receive screening tests for the disease (Calonge, 2004). People at higher risk for syphilis include men who have sex with men and engage in high-risk sexual behavior, commercial sex workers, persons who exchange sex for drugs, and those in adult correctional facilities. The CDC recommends that HIV testing should be considered in the initial evaluation of all patients with syphilitic infection and that screening for hepatitis B and C, gonorrhea, and chlamydial infection also should be considered. The presence of chancres increases the risk of HIV acquisition twofold to fivefold (Greenblatt et al, 1988; Stamm et al, 1988).

Treatment

Benzathine penicillin G (2.4 million units intramuscularly as a single dose) remains the treatment of choice for adults with primary, secondary, or early latent syphilis. Other parenteral preparations or oral penicillin are not acceptable substitutes. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is a reaction consisting of headache, myalgia, fever, tachycardia, and increased respiratory rate that occurs within the first 24 hours after treatment with penicillin. Patients should be warned about the reaction, and it is usually managed with bed rest and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents. It may cause fetal distress and preterm labor in pregnant women. If the patient has penicillin allergy, doxycycline, 100 mg by mouth twice daily for 14 days, or tetracycline, 500 orally for 14 days, have been used as alternatives. Close follow-up of patents receiving alteratives to the recommended benzathine penicillin regimen is critical.

For late latent syphilis, latent syphilis of unknown duration, or tertiary syphilis with no evidence of neurosyphilis, benzathine penicillin, 2.4 million units intramuscular injection should be repeated weekly for a total of three doses (total dose of 7.2 million units) or doxycycline therapy extended for a total of 4 weeks. In pregnancy, the alternative regimens of doxycycline and tetracycline should not be used and desensitization to penicillin is recommended if the patient has a penicillin allergy. Small studies have shown that azithromycin or ceftriaxone may be potential alternatives for early syphilis, but insufficient data are available to make definitive recommendations (Augenbraun and Workowski, 1999; Gruber et al, 2000; Hook et al, 2002).

Neurosyphilis and syphilitic eye disease are treated with aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 3 to 4 million units intravenously every 4 hours for 10 to 14 days, or with procaine penicillin G, 2.4 million units intramuscularly once daily, plus probenecid, 500 mg orally four times daily, with both drugs given for 10 to 14 days. Probenecid cannot be used in patients with an allergy to sulfa. The CDC recommends consideration of treatment with benzathine penicillin, 2.4 million units intramuscularly once a week for 3 weeks after completion of the neurosyphilis treatment regimen, to provide total duration of therapy comparable to that of late syphilis.

Patients should be followed with nontreponemal antibody titers at 6 and 12 month. Patients with HIV should be followed at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 months. A fourfold decrease in antibody titer is usually reflective of cure. The rate of treatment failure ranges from 4% to 21% (Parkes et al, 2004). Patients with treatment failure should be re-treated, and cerebrospinal fluid should be examined to exclude neurosyphilis. Patients with neurosyphilis require repeat examination of cerebrospinal fluid 3 to 6 months after therapy and every 6 months afterward until normal results are achieved.

Lymphogranuloma Venereum

Diagnosis

Lymphogranuloma venereum is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis types L1, L2, and L3 and is extremely rare in the United States. It still persists in parts of Africa, Asia, South America, and the Caribbean (Mabey and Peeling, 2002). The incubation period ranges from 3 to 30 days. The initial manifestation of infection is usually a single, painless ulcer on the penis, anus, or vulvovaginal area that goes unnoticed. Patients usually present with painful unilateral suppurative inguinal adenopathy and constitutional symptoms that occur 2 to 6 weeks after resolution of the ulcer (Figs. 13-10 and 13-11). Women and homosexual men may present with proctocolitis and perirectal or deep iliac lymph node enlargement if the primary lesion arises from the rectum or cervix. Significant tissue injury and scarring may occur, leading to labial fenestration, urethral destruction, anorectal fistulae, and elephantiasis of the penis, scrotum, or labia.

The diagnosis is mainly clinical and cultures are positive in only 30% to 50% of cases. Complement fixation or indirect fluorescence antibody titers can confirm diagnosis. A complement fixation titer greater than 64 is diagnostic of infection. Other causes of inguinal adenopathy should be excluded.

Treatment

Antibiotic therapy for 3 weeks is necessary, using either doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily, or erythromycin base, 500 mg four times daily. Doxycycline is contraindicated in pregnant and lactating women. Patients should be followed clinically until symptoms resolve. Sexual partners should be examined, tested for urethral or cervical infection, and treated if sexual relations occurred within 30 days of the onset of symptoms.

Chlamydia Trachomatis Infection

Diagnosis

Infection with C. trachomatis is the most common bacterial STI in the United States and the most common worldwide. In the United States it is most prevalent in sexually active adolescents and young adults. Virulent serotypes include D, E, F, G, H, I, J, and K. The incubation period ranges from 3 to 14 days.

The majority of both men and women are asymptomatic. Approximately 50% of men experience lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to urethritis, epididymitis, or prostatitis and may notice clear or white urethral discharge. C. trachomatis is the most common cause of epididymitis in young men. Approximately 75% of women are asymptomatic, and 40% with untreated infection will develop pelvic inflammatory disease (Rees, 1980). The squamous cells of vaginal epithelium are relatively resistant to infection with C. trachomatis, but the columnar cells of the cervix are not. A mucopurulent endocervical discharge may be present. Scarring of the fallopian tubes from chlamydial infection puts patients at risk for recurrent pelvic inflammatory disease with vaginal flora, ectopic pregnancy, pelvic pain, and infertility (Simms and Stephenson, 2000).

Chlamydia may also be transmitted to newborns during vaginal birth through exposure of the mother’s infected cervix. Neonates may contract ocular, oropharyngeal, respiratory, urogenital, or rectal infection.

Selective screening has been shown to reduce the incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease (Scholes et al, 1996). Sexually active women should be screened annually until age 26. Older women should be screened if risk factors such as a new sexual partner are present. In women, screening may be accomplished by (1) a nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) performed on an endocervical swab specimen, if a pelvic examination is acceptable; otherwise, an NAAT may be performed on urine; (2) an unamplified nucleic acid hybridization test, an enzyme immunoassay, or direct fluorescent antibody test performed on an endocervical swab specimen; or (3) culture performed on an endocervical swab specimen. In men, the options remain the same: using intraurethral samples or urine.

NAATs utilizing PCR assays for urine are a highly sensitive and noninvasive means of screening men and women for chlamydial infection. NAATs have doubled the detection rate for asymptomatic infections compared with culture and antigen tests (Black et al, 2002; Watson et al, 2002). This method should not replace pelvic examination or endocervical culture in symptomatic women because antibiotic sensitivity cannot be determined. Specimens for culture can be obtained from urethral or cervical swabs, urine, or prostatic fluid. However, NAAT remains an alternative in patients when culture is not possible due to logistics or noncompliance. Urine NAAT is only slightly less sensitive than endocervical swab and because of its noninvasive nature can be used in venues where pelvic examinations are not performed, such as schools and prisons (Black et al, 2002). NAATs may be used with urine or vaginal specimens but not oral or rectal samples. NAATs to test for cure should not be performed less than 3 weeks after treatment has been completed because dead organisms that may still be present will yield a false-positive test. NAATs are available that test for infection with both Chlamydia and N. gonorrhoeae from one sample; however, a positive result is nondiscriminatory between the two diseases and therefore further testing would be needed to determine which disease is present.

Treatment

Azithromycin, 1 g by mouth as a single dose, or doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily for 7 days, is the primary treatment and both are equally effective (Lau and Qureshi, 2002). Alternative therapies include erythromycin base, 500 mg four times daily, erythromycin ethylsuccinate, 800 mg four times daily, ofloxacin, 300 mg twice daily, or levofloxacin, 500 mg once daily for 7 days. Doxycycline, erythromycin estolate, and ofloxacin are contraindicated during pregnancy. Erythromycin base, erythromycin ethylsuccinate, and azithromycin are safe during pregnancy. Another alternative in pregnant women includes amoxicillin, 500 mg three times per day for 7 days. Partners should be examined, tested, and treated. Patients should refrain from sexual intercourse until both their and their partner’s treatment is completed or 7 days after single-dose therapy. Reculture for cure is not needed for patients treated with doxycycline or a quinolone antibiotic. Reculture is recommended 3 weeks after treatment with erythromycin because cure rates are lower with this regimen, in pregnant women, or if the patient has persistent symptoms. However, patients with Chlamydia are at high risk for reinfection and should be rescreened 3 to 4 months after treatment.

All sexual partners who came in contact with the patient within 60 days of diagnosis or symptom onset should be evaluated, tested, and treated for both N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis. If more than 60 days has passed, the most recent sexual partner should be evaluated and treated. Sexual activity should be avoided until both partners complete treatment and are symptom free.

Gonorrhea

Diagnosis

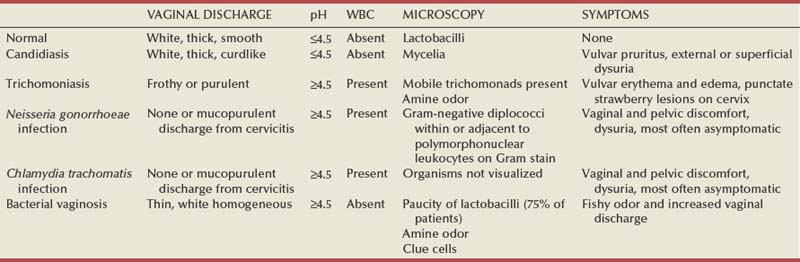

Gonorrhea is caused by the gram-negative diplococcus Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The incubation period ranges from 3 to 14 days. Risk of infection after one exposure is 10% in men and 40% in women. Men will usually experience lower urinary tract symptoms attributed to urethritis, epididymitis, proctitis, or prostatitis, with associated mucopurulent urethral discharge. Women are frequently asymptomatic but may have symptoms of vaginal and pelvic discomfort or dysuria. As with C. trachomatis the vaginal epithelium is resistant to infection with N. gonorrhoeae but the cervix is not. A mucopurulent endocervical discharge may be present (Table 13–3). Both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease and its subsequent complications. Manifestations of gonococcal dissemination are rare today and include arthritis, dermatitis, meningitis, and endocarditis.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screenings for gonorrhea to those at increased risk for infection, including women with previous gonorrhea infection or other STIs; women with new or multiple sex partners, inconsistent condom use, sex, and drug use; and women in certain demographic groups and those living in high-prevalence areas. Screening may be done by endocervical culture or can be performed with newer screening tests, including NAAT and nucleic acid hybridization tests using vaginal, urethral (men only), or urine specimens (U.S. Preventative Services Task Force, 2005; CDC, 2010b). In case of suspected or documented treatment failure, culture and sensitivity are important to monitor antibiotic susceptibility and resistance. Culture may be performed on urethral exudates if present. Patients found to have gonorrhea should be tested for other STIs, including chlamydia, syphilis, and HIV.

Treatment

The most highly recommended treatment for gonorrhea is ceftriaxone, 250 mg intramuscularly as a single dose. It produces high, sustained blood levels that result in cure in about 99% of uncomplicated cases at all anatomic sites, including the pharnyx, which often goes undiagnosed. If treatment with ceftriaxone is not possible, a single oral dose of cefixime (400 mg) is an acceptable alternative that provides a high cure rate for uncomplicated urogenital and anorectal infection but is less effective for pharyngeal infection. Other single-dose cephalosporins, including ceftizoxime 500 mg IM, cefoxitin 2 g IM with probenacid 1 g orally, and cefotaxime 500 mg IM, have been shown to be effective as alternative regimens for uncomplicated urogenital or anorectal infection but offer no advantage over the recommended regimens.

The CDC no longer recommends quinolones for the treatment of gonorrhea in the United States based on data indicating widespread resistance.

Spectinomycin (not available in the United States), 2 g intramuscularly, can be used as an alternative in patients allergic to cephalosporins and during pregnancy. In the United States, azithromycin 2 g orally can be considered for pregnant women who cannot tolerate cephalosporins. It is not considered effective for pharyngeal infection.

Patients with gonorrhea are often coinfected with C. trachomatis. It has been recommended that patients undergo simultaneous dual treatment because the cost of treatment is less than that of chlamydial testing. Single-dose regimens given in the office also ensure compliance in patients who may otherwise not be able to afford the medication, comply with treatment, or return for follow-up. Patients undergoing dual therapy for chlamydial infection should receive azithromycin, 1.0 g as a single dose, or doxycycline, 100 mg twice a day for 7 days (or other acceptable treatment regimen) in addition to one of the previously mentioned regimens for infection with N. gonorrhoeae.

All sexual partners who came in contact with the patient within 60 days of diagnosis or symptom onset should be evaluated, tested, and treated for both N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis. If more than 60 days has passed, the most recent sexual partner should be evaluated and treated. Sexual activity should be avoided until both partners complete treatment and are symptom free.

Trichomoniasis

Diagnosis

Trichomoniasis is one of the most common STIs, with approximately 174 million new cases reported worldwide each year and more than 8 million new cases reported yearly in North America (WHO, 1999). There is an increased incidence in developing countries and in women who have had multiple sexual partners. It is caused by the flagellated protozoan Trichomonas vaginalis, which can inhabit the vagina, urethra, Bartholin glands, Skene glands, and prostate. It does not infect the mouth, and rectal prevalence is low. The human is its only known host. The incubation period ranges from 4 to 28 days.

Trichomoniasis is typically asymptomatic in men but may produce short-lived symptoms of urethral discharge, dysuria, and urinary urgency. Fifty percent of women are asymptomatic. When present, clinical manifestations in women include the sudden onset of a frothy white or green, foul-smelling vaginal discharge, pruritus, and erythema. Other symptoms include dyspareunia, suprapubic discomfort, and urinary urgency. It has been associated with premature labor in pregnant women and with increased risk of HIV transmission (Cotch et al, 1997; Sorvillo et al, 1998).

Clinical examination in women may reveal a frothy discharge and the characteristic “strawberry vulva” or “strawberry cervix.” However, clinical assessment alone is not specific enough for diagnosis. Typically, the vaginal discharge has an elevated pH. The motile protozoa, which are one to four times the size of polymorphonuclear cells, can also be seen on vaginal wet-mount smear or microscopic examination of urine. In men, the diagnosis can be made with urethral, urine, or semen culture or microscopic examination of the urine (preferably voiding bottle No. 1). Standard culture, transport culture kits, enzyme immunoassay, nucleic acid amplification, and immunofluorescence techniques are also available for confirmatory testing. Nucleic acid amplification tests have the highest sensitivity for diagnosis in men (Nye et al, 2009).

Treatment

Infected individuals and their sexual partners should be treated to prevent recurrence of infection. Recommended regimens include a single oral 2.0 g dose of either metronidazole or tinidazole. The 2 g metronidazole regimen may be used during pregnancy; however, the safety of tinidazole in pregnancy has not been established. For nonpregnant treatment failures a longer course of metronidazole, 500 mg twice daily for 7 days, is recommended. The dosing regimens appear equally effective, but side effects, especially gastrointestinal side effects, are more common with the high-dose single therapy. Patients must abstain from alcohol consumption during therapy and for 24 hours after completion of metronidazole and for 72 hours after completion of tinidazole. Repeat testing at 5 to 7 days and 30 days should be performed if symptoms fail to resolve and treatment failure is suspected, and a course of metronidazole, 500 mg orally twice a day for 7 days, should be repeated, or 2 g oral treatment with tinidazole or metronidazole once daily for 5 days may be tried. Metronidazole gel for intravaginal application is available but is less than 50% as effective as oral treatment. Patients allergic to metronidazole should be desensitized. Clotrimazole and other agents have been tried as local intravaginal applications but have not been found to be effective (duBouchet et al, 1997).

Genital Warts

Diagnosis

Genital warts (condylomata acuminata) are caused by HPV. HPV is a DNA-containing virus that is spread by direct skin-to-skin contact. Over 100 types of HPV exist, and over 30 types can infect the genital area. Risk factors for acquiring HPV include multiple sexual partners, early age at onset of sexual intercourse, and having a sexual partner with HPV. Most infections are subclinical and asymptomatic. It has been shown that 60% of a group of female college students followed by Papanicolaou smear every 6 months for 3 years were infected with HPV at some point. The median duration of HPV infection was 8 months, with only 9% remaining infected after 2 years (Ho et al, 1998).

External visible warts are typically caused by HPV types 6 and 11. Patients may be infected with more than one type of HPV. Genital warts may appear anywhere on the external genitalia (Figs. 13-12 to 13-14). It has been suggested that inoculation occurs at the site of genital microtrauma (Frydenberg and Malek, 1993). HPV has also been found on the cervix, vagina, urethra, anus, and mucous membranes such as the conjunctiva, mouth, and nasal passages. Intra-anal warts are contracted via receptive anal sex. However, perianal warts are contracted by skin-to-skin contact and not exclusively through receptive anal intercourse.

Types 6 and 11 HPV are low risk for conversion to invasive carcinoma of the external genitalia. Some other types present in the anogenital region. Types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, and 51 have been associated with cervical dysplasia and neoplasm in women and squamous intraepithelial neoplasia in men (Syrjanen 1981; Adam et al, 2000; Kulasingam et al, 2002). Over 99% of cervical cancers and 84% of anal cancers are associated with HPV, most commonly HPV 16 and 18 (Frisch et al, 1997; Walboomers et al, 1999; Kulasingam et al, 2002). Because HPV progresses rapidly in HIV-infected women, cervical cancer is considered one of the illnesses that defines the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Smoking may increase the risk of dysplastic progression and malignancy in both men and women.

In women, HPV may be associated with nonspecific symptoms, such as vulvodynia or pruritus. Malodorous vaginal discharge may also be a presenting sign, and the high rate of coinfection with other STIs observed in this setting may be a contributing factor.

The diagnosis is usually made through the visualization or palpation of nontender papillomatous genital lesions. Aceto-whitening with 3% to 5% acetic acid placed on a towel and wrapped around the genitalia may show subclinical, flat condylomata appearing as whitish areas; however, because it is not specific for HPV infection, it is not recommended as a routine screening procedure. When this method was used it was shown that 50% to 77% of steady male partners of women with HPV infection and/or cervical neoplasia had subclinical HPV infection (Schneider et al, 1988). Conversely, female partners of men with genital warts have a high incidence of HPV infection (Campion et al, 1985). The benefit of evaluating and treating asymptomatic sexual partners of women with genital warts or abnormal Papanicolaou smears remains unclear. Therefore, routine androscopy is not recommended. Biopsies of genital warts are not routinely needed but should be undertaken in all instances of atypical, pigmented, indurated, fixed, or ulcerated warts. In addition, biopsy should be performed if the lesions persist or worsen after treatment and in immunocompromised patients.

Treatment

The CDC currently recommends that patients with genital warts be informed that HPV and recurrence is common among sexually active persons, the incubation period can be long and variable, and duration of infection and methods of prevention are not definitively known. The choice of therapy for genital warts depends on several factors, including wart size, number, and location and patient and physician preference. Because genital warts spontaneously resolve with time, observation remains an option. Therapy can be patient applied or provider applied. Patient-applied therapies are less expensive and may be more effective than provider-applied therapy (Langley et al, 1999; Arican et al, 2004). Patients must be able to identify and access the lesion and be capable of carefully following the product instructions.

Recommended treatment choices for patient-applied therapy include podofilox 0.5% solution or gel, imiquimod 5% cream, or sinecatechins 15% ointment. Podofilox solution should be applied every 12 hours for 3 days, then off for 4 days with the option to repeat the treatment cycle four times. The total volume of solution used should not exceed 0.5 mL/day, and the total wart area should not be greater than 10 cm2. It may be helpful to demonstrate the first application in the office. Imiquimod cream should be applied three times per week at bedtime for up to 16 weeks. The area should be thoroughly washed 6 to 10 hours after application. Imiquimod should not be used on vaginal lesions because it has been reported to cause chronic ulceration. Sinecatechin ointment (0.5 cm strand of ointment) should be applied three times daily using a finger to ensure a thin film of ointment until the wart completely clears, but no longer than 16 weeks. It should not be washed off after use. In addition, sinecathecin should not be used in immunocompromised persons, HIV-infected persons, or persons with genital herpes because the safety and efficacy in these populations has not been established. The safety of podofilox, imiquimod, and sinecatechin in pregnancy is unknown. Both imiquimod and sinecatechin may weaken condoms and vaginal diaphragms.

Options for provider-applied therapy include cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen, electrosurgery, laser therapy, podophyllin resin 10% to 25%, trichloroacetic acid (TCA) or bichloroacetic acid (BCA) 80% to 90%, or surgical excision. Surgical excision may be accomplished by electrocautery or sharply with a tangential incision. Bleeding can generally be controlled with electrocautery or silver nitrate application. Surgical therapies appear to be equally effective with regard to clearance rates (Wiley et al, 2002). The advantages of surgical excision are that large warts or large areas can be addressed at one time. Carbon dioxide laser therapy is an alternative option for treatment.

Podophyllin 10% to 25% in compound tincture of benzoin is applied once and washed thoroughly 1 to 4 hours after treatment. Treatment may be repeated weekly as needed. The total volume of solution used should not exceed 0.5 mL, and the total wart area treated should not be greater than 10 cm2 per session. In addition, the area being treated should not contain any open wounds or lesions. Podophyllin is contraindicated during pregnancy. TCA and BCA should be carefully applied with a cotton-tipped applicator only to the warts at 1- to 2-week intervals. Patients will complain of a burning sensation, which should resolve in 2 to 5 minutes. Acid that does not react should be removed with baking soda or talc. TCA and BCA are not recommended for keratinized or large warts. TCA is not absorbed and may be used during pregnancy.

Women with genital warts or a history of exposure should seek prompt gynecologic evaluation of the vagina and cervix. In the past, extensive vulvar lesions were treated with 5-fluorouracil cream but it was reported to cause ulceration and acquired adenosis and its use is no longer recommended.

Large or extensive lesions surrounding the urethral meatus may herald the presence of urethral or bladder condylomata, warranting cystourethroscopy. Urethral or bladder lesions should be cystoscopically excised. Intraurethral 5% 5-fluorouracil cream used twice weekly may be useful. However, its use is limited by the great amount of inflammation produced. Cystoscopic evaluation should be considered with caution because of the risk of transmitting the infection beyond the urethra and into the bladder. Considerations might include many and proximal urethral condylomata or other factors that would heighten suspicion for intravesical papillomas. We try to avoid traversing the external sphincter when performing limited urethroscopic examinations for the diagnosis of urethral condyloma or for the treatment of more distal lesions. Frequent serial ultrasound examinations of the distended bladder have been used for long-term surveillance of patients to check for recurrence of urethral condylomata.

HPV Vaccine

Two virus-like particle vaccines for the prevention of HPV-associated conditions are availble. Gardasil (Merck and Co., Inc.) is a quadrivalent vaccine against HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 and is approved by the FDA for use in males and females for the prevention of HPV-associated conditions such as cervical cancer, cervical cancer precursors, anal cancer and associated precancerous lesions, and anogenital warts. Cervarix (GlaxoSmithKline, PLC.), a bivalent vaccine against HPV types 16 and 18, is approved for use in females for the prevention of cervical cancer and associated precancerous lesions.

Both vaccines demonstrate good efficacy against cervical cancer and high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia caused by HPV 16 and HPV 18, if administered before the initial exposure to these HPV types (Harper et al, 2004; Villa et al, 2005; FUTURE II Study Group, 2007; Garland et al, 2007). In addition, the quadrivalent vaccine protects against condylomata acuminata caused by HPV 6 and 11 and vulvar and vaginal precancerous lesions (FUTURE II Study Group, 2007; Joura et al, 2007).

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends vaccination with either vaccine for the prevention of cervicial cancer and precancers. The quadrivalent vaccination may also be used for prevention of genital warts and other HPV-associated conditions such as vulvar cancers and precancers. The vaccines are most effective when all doses are administered before sexual contact. Either vaccine is recommended for 11- and 12-year-old girls and for females aged 13 to 26 years who did not receive or complete the vaccine series when they were younger. Vaccination may begin at age 9 when appropriate. The quadrivalent vaccine can be used in males age 9 to 26 years old to prevent genital warts (CDC, 2010). The length of immunity has not been definitively determined, but in phase 2 follow-up studies both the quadrivalent and bivalent vaccines demonstrated high immunogenic levels for more than 5 years (Villa et al, 2006; Harper et al, 2008). Further research will determine how long immunity will last and if a booster dose will be needed. Vaccination provides less protection to those who have already been infected with one or more of the four vaccine HPV types; however, vaccination is still recommended for protection against the other vaccine subtypes. Unlike the CDC’s guidelines, the American Cancer Society does not recommend universal vaccination among women aged 19 to 26 years because of a probable reduction in efficacy as the number of lifetime sexual partners rises (Saslow et al, 2007). It is important to inform girls and women that they should continue cervical Pap screening even if they have been vaccinated.

Molluscum Contagiosum

Diagnosis

Molluscum contagiosum virus (MCV) is a double-stranded DNA virus that belongs to the Poxviridae family and has worldwide geographic distribution. There are four known subtypes of MCV, but the subtype does not appear to influence disease presentation or course (Nakamura et al, 1995). MCV-1 is the most prevalent in the United States, whereas types 2 and 3 are more prevalent in Europe, Australia, and in HIV-infected patients (Thompson et al, 1990, 1992; Porter and Archard, 1992). The incubation period ranges from 14 to 50 days (Fenner et al, 2001). MCV may be transmitted by skin-to-skin contact, fomites, or self-inoculation. It was once believed to cause only a benign, self-limiting childhood syndrome but is now also considered an STI in adolescents and adults. In children, lesions usually occur in clusters on the face and neck, chest, back, and extremities. In adults and adolescents it is most commonly transmitted by sexual contact, and lesions most frequently appear in the genital and inguinal regions, the inner thighs, and perineum. It less commonly affects mucosal areas such as the conjunctiva and oral mucosa. In children it may spread by self-inoculation to the genital area.

MCV primarily infects the squamous epithelium and manifests as smooth, round, pearly papules that are 2 to 5 mm in diameter, with a subtle central umbilication (Figs. 13-15 and 13-16). The lesions may have an erythematous or hypopigmented halo at the base. The papules are typically asymptomatic but may be associated with an eczematous, pruritic reaction. Giant lesions, more than 5 mm, can occur and seem to be more common in immunocompromised patients. In immunocompetent persons the lesions usually spontaneously resolve within a few months and usually by 1 year but may take up to 5 years (Gottlieb and Myskowski, 1994; Smith et al, 1999).

Diagnosis is usually made on clinical suspicion and may be incidental. If confirmation is necessary, hematoxylin and eosin staining of a biopsy specimen may be performed. The presence of acidophilic, hyaline-filled Henderson-Patterson bodies, also known as molluscum contagiosum bodies, are pathognomonic. A squash preparation with methylene blue will also reveal the molluscum contagiosum bodies. It is recommended that the patients be tested for other STIs such as gonorrhea, chlamydial infection, and syphilis and carefully examined for coexistent condylomata acuminata and pediculosis pubis (Waugh, 1998). Careful consideration should also be given to HIV testing in patients with extensive multisite lesions, especially those involving the head and neck, and in lesions with a poor response to treatment.

Treatment

In most cases, MCV is benign and self-limiting and therefore requires no treatment. If the patient desires or if spread is of particular concern, destructive therapy with cautery, curettage, or cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen are sound options. All of these methods cause discomfort and may result in scarring. Lidocaine/prilocaine cream applied in an occlusive manner before the procedure should assist with discomfort. A topical antibiotic preparation should be applied afterward to prevent secondary infection.

Other topical therapies such as TCA, cantharidin, tretinoin, and podophyllotoxin have been reported for the treatment of MCV (Smith and Skelton, 2002). None is approved by the U.S. FDA for this indication, and all may result in pain and inflammation, especially in the genital area. Immunotherapy with imiquimod cream, either 1% or 5%, applied to lesions three times daily has been shown to be effective and appears especially useful in patients infected with HIV (Syed et al, 1998; Liota et al, 2000). Small studies in HIV-infected patients with recalcitrant lesions have also reported success with 1% cidofovir cream (Calista, 2000; Torro et al, 2000). Currently cidofovir is commercially available only in an intravenous preparation.

Scabies

Diagnosis

Scabies is caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei. In adults, scabies is usually sexually transmitted, but this is not the case in children. The incubation period ranges from 2 to 6 weeks. Wavy, elongated papules are characteristic of the mite burrow. Eruption with pruritus is caused by an immune reaction to the mites, their eggs, and their feces. Susceptible areas include the penile shaft and glands, areolae, finger webs, and auxiliary folds (Fig. 13–17). Confirming the diagnosis may require microscopic evidence of the mite or eggs, which is retrieved by scraping the burrow with a scalpel blade coated with mineral oil. It can also usually be demonstrated if a thin shaving of skin from a papule is removed and placed on a glass slide and digested with heat and 10% potassium hydroxide.

Norwegian scabies, also known as crusted scabies, is caused by the same mite but occurs in immunocompromised or debilitated persons. The parasite burden is much greater, resulting in many severe, deep, hyperkeratotic crusts that are characteristically less pruritic, most likely secondary to the host’s immune compromise. The incubation period is shorter in patients with Norwegian scabies—usually less than 2 weeks (Kolar and Rapini, 1991).

Treatment

Permethrin cream (5%) should be applied to all areas of the body from the neck down and washed off 8 to 14 hours later. An alternative to permethrin cream is oral ivermectin, 200 μg/kg in a single dose, repeated 2 weeks later. Ivermectin therapy has been shown to be equally effective as permethrin cream and lindane lotion but is more expensive (Wendel and Rompalo, 2002). For intolterance to permethrin or ivermectin, or treatment failure, the alternative is lindane (1%) lotion or cream applied in a similar fashion and removed after 8 hours. If necessary, treatment may be repeated in 1 week. Lindane should not be used after a bath and is contraindicated in children younger than 2 years of age, pregnant and lactating women, and patients with extensive dermatitis. Serious adverse side effects from lindane include seizures and aplastic anemia. For young children or pregnant/lactating women, sulfur (3% to 6%) applied on 3 consecutive nights is an option. Sexual partners and close contacts should also be treated. Treatment of Norwegian scabies may require combined oral and topical therapy or repeated treatments. Lindane should be avoided in these patients because of their excessive dermatitis, which may lead to increased absorption.

Clothing or bed linen that may have been contaminated should be washed and dried by machine on a hot cycle or dry cleaned and removed from body contact for at least 72 hours. It should be noted that itching may persist for 2 to 3 weeks after adequate therapy.

Pediculosis Pubis

Diagnosis

Pediculosis pubis infection (phthiriasis, pubic lice) is caused by infection with the human louse Phthirus pubis. This species of lice has a proclivity for the pubic area, but the nits and lice can be seen in other areas with hair, such as the axilla, eyelashes, or scalp hair. The saliva of the lice causes a maculopapular or urticarial reaction in sensitized people and results in intense itching of the affected area. The presence of eggs (nits) attached to the hair shaft near the skin surface or the actual presence of an imbedded louse in the hair follicle is diagnostic. These lice can often be seen with the naked eye or with low-power magnification.

Treatment

Recommended regimens include permethrin cream rinse (1%) or pyrethrins with piperonyl butoxide applied to affected areas of the body and washed off 10 minutes later. Alternative regimen in the case of patients who cannot tolerate the recommended regimens or for treatment failure, by patients with extensive dermatitis, include malathion 0.5% lotion applied for 8 to 12 hours and then washed off, or ivermectin 250 mcg/kg orally, repeated in 2 weeks. Although topical insecticidal preparations are the preferred treatment, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole can eliminate infections (Hutchinson and Farquhar, 1982). Pediculosis of the eyelashes is treated by applying an occlusive ophthalmic ointment, such as sterile petrolatum, to the eyelid margins two times a day for 10 days. The medicated topical agents described above cannot be used on or near the eyes. Sexual partners within the past 30 days should also be treated. Clothing or bed linen that may have been contaminated should be washed and dried by machine on a hot cycle or dry cleaned and removed from body contact for at least 72 hours.

Overview of Other Sexually Associated Infections

Mollicutes

Ureaplasma urealyticum, Mycoplasma hominis, and Mycoplasma genitalium are considered commensal organisms of the genital tract in both men and women. At least 60% of asymptomatic women have been shown to harbor Ureaplasma in their genital tract. However, these organisms have also been implicated in cases of chronic prostatitis in men, urgency/frequency syndromes in women, and up to 40% of nongonococcal urethritis cases. They have been isolated as the sole pathogen in symptomatic patients, who respond to antimicrobial therapy targeting these mollicutes. Women, especially young sexually active women, with urgency-frequency syndrome with or without dysuria who have repeatedly negative urine cultures may benefit from culture and subsequent treatment for Mycoplasma and Ureaplasma. Culturing for this organism should also be considered in men with symptoms previously attributed to prostatitis or in men with prior history of STI exposure or infection.

Mollicutes have complex nutritional requirements and will not grow on routine culture medium. They cannot be visualized well with Gram stain. Confirming the presence of the organism from cervical, urethral, or urine specimens requires the visualization of characteristic colonies on specialized agar and color changes of urea broth. The organisms are highly sensitive to drying and must be promptly placed in the proper medium and delivered to the laboratory. If cultures are positive, treatment is recommended with subsequent surveillance for improvement in symptoms. Sexual partners should be evaluated and treated and no sexual activity is advised for 2 weeks during treatment.

Historically this group of organisms was highly sensitive to tetracycline. Today, however, up to 30% of strains may be resistant, which may explain persistent symptoms in those patients treated empirically for nongonococcal urethritis or presumed Chlamydia infection. Most tetracycline-resistant strains remain sensitive to erythromycin. Currently, the initial recommended therapy is doxycycline, 100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks, or a single 1-g dose of azithromycin, which can be repeated after 10 to 14 days if needed. Other alternatives include erythromycin, 500 mg four times daily, or ofloxacin, 300 mg twice daily for 10 to 14 days. Sexual partners should be evaluated and treated as well as refrain from sexual activity for 2 weeks during treatment.

Bacterial Vaginosis

Diagnosis

Bacterial vaginosis is caused by the overgrowth of Gardnerella vaginalis, anaerobic organisms, and Mycoplasma hominis and inhibition of normal vaginal flora, particularly Lactobacillus. The cause of disruption in the microflora has not been elucidated. Bacterial vaginosis increases a woman’s risk of contracting infection with HIV, is associated with increased complications in pregnancy, and may be involved in the pathogenesis of pelvic inflammatory disease.

Patients may complain of a malodorous vaginal discharge, particularly after sexual intercourse, and nonspecific low-grade genital discomfort. Risk factors for bacterial vaginosis include an increased number of sexual partners, douching, abnormal uterine bleeding, and contraceptive use.

To examine vaginal discharge, a wet mount is performed by adding 2 drops of normal saline to the vaginal discharge on one microscope slide and 2 drops of 10% potassium hydroxide to another sample on a second slide. The whiff test is performed immediately after adding the potassium hydroxide. A fishy odor secondary to the release of amines is suggestive of bacterial vaginosis. The slide is then examined under the microscope using low and high power. Clue cells are white blood cells with bacteria attached to the cell membrane. Three of four of the following factors must be met to confirm the diagnosis: (1) thin, white vaginal discharge that covers the vagina, (2) vaginal pH greater than 4.5, (3) clue cells, and (4) positive whiff test. Vaginal cultures are not helpful in this setting; however, a Gram stain of the vaginal discharge can identify the relative change in concentrations of normal bacterial flora. There are commercially available DNA probes and card tests that can be useful for office diagnosis. Routine operative prophylaxis with metronidazole before hysterectomy has been shown to reduce postoperative infectious complications.

Treatment

Recommended primary therapy includes metronidazole, 500 mg twice daily for 7 days; clindamycin cream, 2% (5 g) intravaginally at bedtime for 7 days; or metronidazole gel, 0.75% (5 g) intravaginally at bedtime for 5 days. Alternative regimens include clindamycin, 300 mg orally twice daily for 7 days; clindamycin ovules, 100 g intravaginally at bedtime for 3 days; tinidazole, 2 g orally once daily for 2 days; or tinidazole, 1 g orally once daily for 5 days. Clindamycin cream and ovules may weaken latex condoms and diaphragms. Factors that disrupt the normal vaginal flora, such as douching, should be avoided. Treatment of the sexual partner has not been shown to prevent recurrence in two randomized trials and is therefore not recommended (Vejtorp et al, 1988; Colli et al, 1997).

Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

Vaginitis caused by Candida albicans is the most common type seen in the clinical setting, but other species of Candida may also cause infection. The organism is present in the normal vagina and can also be found in the coronal sulcus of the penis. Sexual transmission with subsequent colonization and infection is possible. Predisposing factors for active infection include hormonal changes resulting from pregnancy or contraception, antibiotic use, systemic corticosteroids, or antimetabolites. Complicated vulvovaginal candidiasis is defined as recurrent, severe, non–C. albicans infections occurring in patients with altered immunity or pregnancy. Characteristically, thick, cheesy vaginal discharge is usually associated with vulvar irritation and itching. Patients may also experience vaginal discomfort, burning, dyspareunia, and external dysuria.

Diagnosis can be confirmed in a woman with signs and symptoms by findings of yeast or pseudohyphae on a wet preparation slide or Gram stain of the vaginal discharge. Often the yeast and pseudohyphae are seen better when 10% potassium hydroxide is used. The pH of the vaginal discharge should be normal (<4.5). A vaginal culture may also be performed and is advised in patients with recurrent infections. Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis is defined as four or more episodes per year, and in 10% to 20% of patients C. glabrata and other candidal species are found.

Treatment

Over-the-counter antifungal vaginal creams, tablets, or suppositories of the topical azole class are generally effective, requiring 1- to 7-day regimens depending on the agent and dosage form. Over-the-counter treatment agents include butoconazole, clotrimazole, miconazole, and tioconazole. The vaginal preparations may weaken latex condoms. Prescription intravaginal agents include butoconazole, nystatin, and terconazole. An alternative to vaginal creams that is both effective and economical is fluconazole, 150 mg, as a single oral dose (Miller, 1997).

Recurring infections or complicated vulvovaginal candidiasis may require extended treatment of 14 days with vaginal preparations or oral fluconazole therapy repeated every 3 days (day 1, 4, and 7) for a total of three doses prior to starting an antifungal maintenance regimen. Patients suffering from recurrent candidal vulvovaginitis require further evaluation to exclude HIV infection, diabetes, or other immune-compromised states, although in most women no cause is found. These patients often do well with maintenance therapy, but 30% to 40% will have recurrence once maintenance therapy is stopped. Treatment of sexual partners is not suggested in general but may be considered in patients with recurrent infections.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STD facts—human papilloma virus. CDC.gov/std/hpv/stdfact-hpv, 2005. [accessed 22.10.10]

Retiano M. Counseling patients with genital warts. Am J Med. 1997;102:38-43.

Sulak PJ. Sexually transmitted diseases. Semin Reprod Med. 2003;21:399-413.

White C, Wardropper AG. Genital herpes simplex infection in women. Clin Dermatol. 1997;15:81-91.

2004 ACOG practice bulletin: clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists, number 57, November 2004. Gynecologic herpes simplex virus infections. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(5):1111-1117.

Adam E, Berkova Z, Daxnerova Z, et al. Papillomavirus detection: demographic and behavioral characteristics influencing the identification of cervical disease. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:257-264.

American Social Health Association/Kaiser Family Foundation. Sexually transmitted diseases in America: how many and at what cost?. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 1998.

Arican O, Suneri F, Bilgie K, Karaoglu A. Topical imiquimod 5% cream in external genital warts: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Dermatol. 2004;31:627-631.

Augenbraun M, Workowski K. Ceftriaxone therapy for syphilis: report from the emerging infections network. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1337-1338.

Baker DA. Diagnosis and treatment of viral STDs in women. Int J Fertil. 1997;42:107-114.

Benedetti J, Corey L, Ashley R. Recurrence rates in genital herpes after symptomatic first-episode infection. Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:847-854.

Berg E, Benson DM, Haraszkiewicz P, et al. High prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in women with urinary infections. Acad Emerg Med. 1996;3:1030-1034.

Black CM, Marrazzo J, Johnson RE, et al. Head-to-head multicenter comparison of DNA probe and nucleic acid amplification tests for Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women performed with an improved reference standard. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3757-3763.

Calista D. Topical cidofovir for severe cutaneous human papillomavirus and molluscum contagiosum infections in patients with HIV/AIDS: a pilot study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14:484-488.

Calonge N. Screening for syphilis infection: recommendation statement. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:362-365.

Campion MJ, Singer A, Clarkson PK, et al. Increased risk of cervical neoplasia in consorts of men with penile condylomata acuminata. Lancet. 1985;1:943.

Cates WJr. Estimates of the incidence and prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases in the United States. American Social Health Association Panel. Sex Transm Dis. 1999;26:S2-S7.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update to CDC’s sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006: fluoroquinolones no longer recommended for treatment of gonococcal infections. MMWR. 2007;56(14):332-336.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Primary and secondary syphilis among men who have sex with men—New York City, 2001. MMWR. 2002;51:853-856.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2009. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2010. MMWR. 2010;59(No. RR-12):1-110.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Summary of notifiable diseases United States, 2008. MMWR. 2008;57(No. 54):18-19.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Expedited partner therapy in the management of sexually transmitted diseases. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2006.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Legal status of expedited partner therapy (EPT). http://www.cdc.gov/std/ept/legal, 2009. [accessed 31.05.09]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FDA licensure of bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine (HPV2, Cervarix) for use in females and updated HPV vaccination recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR. 2010;59(20):626-629.

Coles FB, Muse AG, Hipp SS. Impact of a mandatory syphilis delivery test on reported cases of congenital syphilis in upstate New York. J Pub Health Manag Proct. 1998;4:50-56.

Colli E, Landoni M, Parazzini F, et al. Treatment of male partners and recurrence of bacterial vaginosis: a randomized trial. Genitourin Med. 1997;73:267-270.

Cotch MF, Pastorek JG2nd, Nugent RP, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery. The Vaginal Infections and Prematurity Study Group. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:353-360.

DiCarlo RP, Martin DH. The clinical diagnosis of genital ulcer disease in men. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:292-298.

duBouchet L, Spence MR, Rein MF, et al. Multicenter comparison of clotrimazole vaginal tablets, oral metronidazole, and vaginal suppositories containing sulfanilamide, aminacrine hydrochloride, and allantoin in the treatment of symptomatic trichomoniasis. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:156-160.

Erbelding E, Vlahov D, Nelson K, et al. Syphilis serology in human immunodeficiency virus infection: evidence for false negative fluorescent treponemal testing. J Infect Dis. 1997;176:1397-1400.

Erbelding E, Zenilman J. Toward better control of sexually transmitted diseases. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:720-721.

Fenner F, Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Virology, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 2001.

Fox KK, del Rio C, Holmes KK, et al. Gonorrhea in the HIV era: a reversal in trends among men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:1-5.

Frisch M, Glimelius B, van deen Brule AJ, et al. Sexually transmitted infection as a cause of anal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1350-1358.

Frydenberg M, Malek RS. Human papillomavirus infection and its relationship to carcinoma of the penis. Urol Annu. 1993;7:185-198.

FUTURE II Study Group. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1915-1927.

Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1928-1943.

Golden M, Marra C, Holmes K. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA. 2003;209:1510-1515.

Goldmeier D, Guallar C. Syphilis: an update. Clin Med. 2003;3:2009-2011.

Gottleib SL, Myskowski PL. Molluscum contagiosum. Int J Dematol. 1994;33:88-92.

Greenblatt RM, Lukehart SA, Plummer FA, et al. Genital ulceration as a risk factor for human immunodeficiency virus infection. AIDS. 1988;2:47-50.

Gruber F, Kastelan M, Cabrijan L, et al. Treatment of early syphilis with azithromycin. J Chemother. 2000;12:240-243.

Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler C, et al. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 364, 2004. 1757–65.2

Harper D, Gall S, Naud P, et al. Sustained immunogenicity and high efficacy against HPV 16/18 related 6.4 years in women vaccinated with Cervarix. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:158-159.

Hart G. Syphilis tests in diagnostic and therapeutic decision making. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:368-376.

Hicks CB, Benson PM, Lupton GP, Tramont EC. Seronegative secondary syphilis in a patient infected with the human immunodeficiency virus with Kaposi sarcoma: a diagnostic dilemma. Ann Intern Med. 1987;107:492-495.

Ho GYF, Bierman R, Beardsley L, et al. Natural history of cervicovaginal papillomavirus infection in young women. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:423-428.

Hook EW3rd, Martin DH, Stephens J, et al. A randomized, comparative pilot study of azithromycin versus benzathine penicillin G for treatment of early syphilis. Sex Transm Dis. 2002;29:486-490.

Hutchinson DB, Farquhar JA. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in the treatment of malaria, toxoplasmosis, and pediculosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1982;4:419.

Johnson PC, Farnie MA. Testing for syphilis. Dermatol Clin. 1994;12:9.

Joura EA, Leodolter S, Hernandez-Avila M, et al. Efficacy of a quadrivalent prophylactic human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against high-grade vulval and vaginal lesions: a combined analysis of three randomised clinical trials. Lancet. 2007;369(9574):1693-1702.

Kolar KA, Rapini RP. Crusted (Norwegian) scabies. Am Fam Phys. 1991;44:1317-1321.

Kulasingam SL, Hughes JP, Kiviat NB, et al. Evaluation of human papillomavirus testing in primary screening for cervical abnormalities: comparison of sensitivity, specificity, and frequency of referral. JAMA. 2002;288:1749-1757.