Vesicourethral Distraction Defects

Enthusiastic use of radical prostatectomy has unfortunately led to increasing experience with patients who have had total obliteration of their vesicourethral anastomosis. In some patients, there is distraction of the vesicourethral anastomosis with either a totally obliterating distraction defect or severe anastomotic stenosis. In addition, with the proposal that bladder tube interposition might enhance continence, a new entity, the stenotic or obliterated vesicourethral anastomosis due to ischemia of the bladder tube, is now encountered.

As with other defects, it is important to accurately determine the length of the defect. This can be accomplished by simultaneous cystography with retrograde urethrography, simultaneous retrograde urethrography and antegrade endoscopy through the suprapubic tube, or both.

There are a number of options for the management of these complex patients. Many have other medical problems, and it has been our observation that many have thick and small bladders, possibly contributing to the difficulty with the initial surgery. The ever-present issue of body habitus also must be considered and, in our opinion, contributes to problems with the initial anastomosis. An indwelling suprapubic tube must always be considered an option. In the individual who is significantly overweight, the results of aggressive reconstruction have not been good. The place for endoscopic techniques is covered later in this section; however, in the case of short-length distractions, we have had good success with aggressive incisions at the 3-o’clock and 9-o’clock positions followed in approximately 3 weeks with repeated incisions. Whether the holmium laser is better than the cold knife can be debated; the hot knife is not necessary. If one must “core through” to establish continuity, in our opinion endoscopic procedures have no place except as discussed later.

In some cases, a continent catheterizable bladder augmentation may indeed be a better operation than aggressive functional reconstruction; however, the very heavy patient makes construction of a functional catheter channel difficult. Diversion must also be entertained, and in patients in whom functional reconstruction is not an obvious choice, it then becomes a primary option.

If functional reconstruction is deemed possible, we think it is a reasonable choice and our technique is as follows. We place the patients in a low lithotomy position and use an abdominal-perineal combined approach. We make a lower midline incision, exposing the bladder and dissecting it from the lateral sidewall and further mobilizing the anterior bladder from beneath the pubis as aggressively as can be safely undertaken from above. We then open the peritoneum and develop the retrovesical space, again taking care to complete the dissection as safely as can be accomplished from above.

A second surgeon then begins the perineal dissection by a curvilinear perineal incision similar to that used for a radical perineal prostatectomy. The dissection is posterior to the transverse perinei musculature (posterior anal triangle) and carried along the anterior rectal wall to the area where fibrosis is encountered from the prior radical prostatectomy dissection. The impulse of the perineal surgeon’s digits can usually be felt adjacent and lateral to the area of fibrosis and distraction at this point. In addition, the abdominal surgeon places a finger at the limits of the retrovesical dissection from above to provide another palpable landmark and to ensure a safe dissection anterior to the rectal wall and posterior to the bladder and trigone. The perineal dissection is then joined to the abdominal dissection, and the rectal wall is completely peeled off the area of fibrosis associated with the distraction defect. We then place drains between the rectum and the distraction defect, encircling the area of fibrosis.

The dissection beneath the pubis is made easier by the excision of an ellipse of the rim of the superior pubic ramus. Total pubectomy is not required. The partial pubectomy can be performed with the reciprocating attachment of the Aesculap surgical drilling device (Aesculap, Tuttlingen, Germany); this makes placement of the sutures technically straightforward and improves the exposure for the dissection and resection of the distraction fibrosis.

At this point, the bladder is opened and the area of the bladder neck is determined. A sound is placed and advanced to the area of obliteration. This allows us to completely resect the well-defined area of fibrosis. The urethral stump is exposed and opened, and the site of the neobladder neck, having been identified, is opened. We marsupialize the bladder epithelium as described by Eggleston and Walsh (1985), place anastomotic sutures in the urethral stump, and pass a stenting catheter.

Before the vesicourethral anastomosis is seated, the omentum is mobilized and placed between the posterior wall of the anastomosis and the anterior rectal wall. We then seat the anastomosis and wrap the omentum around the area of anastomosis, tagging it into place. The lateral vesical spaces are drained with closed-suction drains, and a suprapubic tube is left in place when the vesicostomy is closed.

Postoperative care is the same as for a radical prostatectomy. The patients are discharged when their drainage and ambulation allow and their diet has been resumed. We evaluate the patients 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively, with the stenting urethral catheter removed and the bladder filled by way of the suprapubic tube.

Because one attempt has failed in these patients, we generally are conservative with the timing of a voiding trial. In some cases, voiding trials are being done at 2 to 3 weeks.

Our series continues to grow, and we continue to have excellent success in reconstruction. We have some patients who deem their continence adequate for their lifestyle; in the others, we have been successful with the placement of an artificial sphincter.

Others have proposed a different approach to these very difficult cases. In patients for whom multiple attempts at dilation or incision of these vesicourethral anastomotic stenoses have failed, Elliott and Boone (2001) proposed making an incision with placement of the UroLume endoprosthesis, followed at an interval by the placement of an artificial sphincter. They initially described nine men treated with this approach; seven of the men were satisfied with the results of their treatment at 17.5 months mean follow-up. Others (Mark et al, 1993; Kaplan, 2004; Anger et al, 2005) have proposed slight modifications of this approach and are also reporting adequate patency and continence in these patients. Additionally, there are centers accumulating experience with either a pure perineal or a pure abdominal approach with good success rates (Herschorn, 2007; Fisch, 2009).

Complex Fistulas of the Posterior Urethra

The increase in the performance of radical prostatectomy has also led to an increased incidence of vesicorectal or vesicourethrorectal fistulas. In most cases, these are small and managed by a transperineal, transanal–trans-sphincteric, or posterior approach. However, some cases are complex, with the fistulas associated with large granulated cavities. The problem is magnified when radiation (brachytherapy, external beam therapy, or both) is part of the equation. With radiation fistulas, a number of centers have gone to diversion with ileal conduit or bowel pouch as opposed to functional reconstruction. These cases have also been managed with the approach described earlier for vesicourethral distraction problems. The omentum, however, serves an even more important purpose in these cases. In addition, with the increasing application of “minimally invasive” modalities for carcinoma of the prostate (i.e., brachytherapy, combined brachytherapy with external beam irradiation, higher dose external beam irradiation, and cryotherapy), the magnitude of complexity of these problems of prostatic urethral fistulas, granulated cavities, and severe rectal injury continues to increase. We have tried to approach these problems aggressively, with preservation of function, where possible.

In many of these cases, salvage prostatectomy can be combined with rectosigmoid resection. In some cases, we have successfully reanastomosed the bladder to the membranous urethra. Preservation of continence has been mixed. Where vesicourethral anastomosis is not possible, a urachal-peritoneal flap combined with a rectus abdominis muscle flap is used to bolster the closed bladder neck and to keep the closed bladder neck from sticking to the back of the pubis. The bladder is augmented, and a continent catheterizable channel is developed. In some cases, the continuity of the colon cannot be reestablished, and a colostomy is performed as distally on the descending portion of the colon as possible. Whenever continuity of the colon can be reestablished, a J-pouch coloanal anastomosis is done. Omentum is used to envelop the rectal closure or to separate the rectal closure from the vesicourethral anastomosis. The combined abdominal-perineal approach that was previously described provides excellent safe exposure for management of these complex situations. The morbidity of this approach has been acceptable.

One must be careful in addressing the irradiated bowel. We had a patient who did well with his surgery for continent catheterizable augmentation and bowel closure, but when his colostomy was reversed, he developed an overwhelming colitis and a refistula, with an eventual septic death. Another patient had a breakdown of his bladder neck closure and to date remains with a large vesicoabdominal fistula. Thus it cannot be overemphasized that these cases must be individualized. When they go well, they go wonderfully well; when they do not, they become a disaster for the patient, the patient’s family, and the surgeons involved.

Zinman recently reported a 10-year experience with the management of rectourethral fistula. That series had 33 patients who had fistulas and who had not been irradiated, and 33 more who had been irradiated. Mean follow-up for the entire series was about 20 months. The review was a retrospective review taken from office records and hospital records. All fistulas were repaired by an anterior transperineal approach using gracilis muscle interposition flaps, and in some cases with a buccal graft. In this series, 100% of the nonirradiated fistulas were successfully closed with a mean follow-up of 20 months, 85% of the irradiated fistulas were closed in a single stage, and 12% required an additional procedure, with an ultimate closure rate of about 97%. In the nonirradiated group, there were no urethral strictures noted with long-term follow-up; 5 recurrent strictures were noted in the irradiated group. In the nonirradiated group, 91% of the patients had their bowel undiverted. In the irradiated group, 39% had long-term bowel diversion. Zinman believes that the use of muscle interposition flaps are integral to achieving good results, and their use of buccal mucosal grafts, where needed to augment the closure of the urinary tract, were also believed to be invaluable (Vanni et al, 2009). Clearly, both an estimation of ultimate urinary and bowel function are integral to the determination of the plan for reconstruction and/or diversion. Also, it must be recognized that the surgical approach chosen both facilitates and limits options (i.e., of the bowel, the urethra, and/or tissue interposition) (Lane et al, 2006).

Key Points: Vesicourethral Distraction Defects and Complex Fistulas of the Posterior Urethra

Curvatures of the Penis

Normal elasticity and compliance of all tissue layers of the penis are critical for erectile function, tumescence, and rigidity. Tissues must expand in all dimensions as the penis engorges with blood; eventually, the tissues of the tunica albuginea and the septal fibers of the corpora cavernosa are stretched to the limits of their compliance, and tumescence is converted to rigidity. In the normal penis, the tissues are symmetrically elastic and the erection is straight. In curvature of the penis, there is relative asymmetry of one aspect of the erect penis. In some cases, this arises from diminished compliance of one aspect of the tunica albuginea or outright foreshortening of one aspect of the erectile bodies.

The term chordee means curvature, but it is commonly used as if it refers to the tissues causing the curvature. This misuse of the term is seen in the statement “the chordee was resected”; properly phrased, “the chordee can be corrected by resecting the inelastic tissues that are causing the chordee.”

Curvatures of the penis can be congenital or acquired. Some confusion also exists in common usage of the term congenital curvature of the penis. The terms congenital curvature of the penis and chordee without hypospadias have often been used interchangeably. We prefer to reserve the term chordee without hypospadias for those patients in whom the meatus is properly located on the tip of the glans penis, yet a ventral curvature is associated with abnormalities of the ventral fascial tissues or corpus spongiosum, or both. It has long been recognized that hypospadias is a condition that is associated in some males with either a diminutive penis or a micropenis. Although a small penis is not diagnostic of hypospadias, it is highly unusual for a patient with hypospadias to have an exceptionally large erect penis. In contrast, other congenital curvatures of the penis (ventral, lateral, or dorsal) are inevitably associated with the finding of a large erect penis. Because the trauma that results in acquired curvature is virtually always associated with intercourse, the occurrence of acquired curvature is nil before the onset of puberty. We have seen some patients in whom there was a history of trauma during vigorous masturbation, but these patients are the exception. Like congenital curvatures of the penis, acquired curvatures may be dorsal, lateral, ventral, or complex.

Types of Congenital Curvature of the Penis

The urethra begins as an epithelial groove in the midline of the ventral surface of the developing penis. As the groove extends, it deepens, with the edges eventually meeting to fuse into a tube. Fusion begins proximally and progresses distally. During normal development, the fusion of the urethral tube eventually reaches the tip of the glans penis. Proliferating mesenchyma surrounds the tube, separating it from the skin, and differentiates to form the corpus spongiosum, Buck fascia, dartos fascia, and overlying ventral skin of the penis. Fetal development of the penis is regulated by testosterone, produced by the fetal testis, which is converted by 5α-reductase to dihydrotestosterone. Dihydrotestosterone acts directly on cells with androgen receptors and on all layers of the male external genitalia. This embryologic process explains the development of the anterior urethra that is unique to males.

Maturation of these tissues into normal structures depends on the same growth factors that control the formation of the urethra. Even though urethral development has progressed normally, mesenchymal tissue development in the penis may be deficient or abnormal and result in dysgenetic and inelastic fascial layers. In unpublished data, Galloway and associates (El-Galley et al, 1997) have shown that at least in hypospadias, there is a deficiency of growth factors in the ventral penile skin. To our knowledge, to date there are no data that show the same growth factor deficiencies for the deeper tissues.

In 1973, Devine and Horton proposed a typing classification for the various congenital curvatures. In type I congenital curvature, the urethral meatus is at the tip of the glans. None of the surrounding layers are normally formed, however, and the epithelial urethra is associated with malfusion of the corpus spongiosum and all the tissues superficial to the urethra. Skin coverage of the epithelial tube is present. In type II, a dysgenetic band of fibrous tissue thought to be derived from the mesenchyma, which would have produced the Buck fascia and the dartos fascia, lies beneath and lateral to the urethra. However, the urethra is contained within a normally developed and fused corpus spongiosum.

In type III, the urethra, corpus spongiosum, and Buck fascia are all normally developed and ventrally fused. However, there is a short area of inelastic tissue in the dartos layer of the penis that causes a relatively sharp bend. Abnormal development of the dartos fascia is frequently associated with complex curvatures. With extensive involvement, the inelastic dartos can be sufficient to restrain the penis and conceal the penile shaft. In many of these cases, there appears to be abnormal prominence of the mons fat pad. These stigmata are thought to be associated with an abnormality in the proper progression of virilization during fetal development.

In type IV, although the urethra, corpus spongiosum, and fascial layers are normally developed, there is relative shortness or inelasticity of one aspect of the tunica albuginea of the corpora cavernosa. Experience has shown that most patients whose congenital curvature is type IV seem to actually demonstrate evidence of a hypercompliance of the tunica albuginea. In these patients, the flaccid penis is normal in size and not necessarily impressively large, whereas the erect penis is large. The tunica albuginea of the corpora cavernosa is required to expand through a wide range, and if there is asymmetry in the compliance of the tunica, curvature occurs. It is not uncommon for patients with type IV curvature to have noticed curvature before puberty; but as they traverse puberty, an increase in the curvature is noted because of the penile hypertrophic growth spurt that occurs during this time.

Type V congenital curvature is also known as the congenital short urethra. This implies that there has been correct fusion of all elements of the penis (i.e., tunica albuginea, urethral epithelium, corpus spongiosum, Buck fascia, dartos fascia, and ventral skin). However, during erection, the correctly fused urethra and corpus spongiosum are not long or compliant enough to match the compliance of the other ventral tissue layers.

If type V congenital curvature exists at all, it occurs so rarely that when it is encountered, one should doubt the findings. Whereas discussion of the condition in the past has centered on the best location to “cut the urethra” during the repair, on the rare occasions when this condition is encountered, it is our belief that it should be diagnosed and treated only by the most experienced surgeons. In general, if the urethral meatus has developed to the tip of the glans, the urethra should not be divided to correct ventral curvature of the penis. Although there will obviously be extremely rare exceptions to this bold statement, if those exceptions are encountered, their existence should still be questioned.

The congenital curvature types I, II, and III represent forms of the hypospadias anomaly, and we prefer to refer to them collectively under the term chordee without hypospadias. This term implies that although the meatus is not improperly placed, curvature is due to inappropriate fetal development of the ventral penile structures. We prefer to refer to the type IV anomaly as congenital curvature of the penis. If a patient has findings of hypercompliance of the corpora cavernosa and a ventral curvature, the patient is diagnosed as having congenital ventral curvature of the penis; and if the hypercompliance causes a lateral curvature, it is referred to as congenital lateral curvature of the penis (left or right). Although, as mentioned, the type V anomaly is so rarely encountered that it deserves its own diagnosis, we believe its correction is best discussed with types I, II, and III, under the category of chordee without hypospadias.

Chordee without Hypospadias in Young Men

Patients with chordee without hypospadias usually present with either ventral curvature or ventral curvature associated with torsion (complex curvature). These young men do not typically have a greater than average stretched penile length (13.1 cm) (Schonfeld and Beebe, 1942) and will have noted curvature throughout life. If prepubescent, they have obvious curvature with erection; if postpubescent, they may offer a history of increasing curvature as they pass through puberty.

In many cases, there are abnormalities of the ventral penile skin. These might consist of either an element of hooded preputial skin or a high insertion of the penoscrotal junction. Although the patients have fusion of the preputial skin, there is also often a wrinkled appearance dorsally that we now recognize to be a form of the classic hooded preputial skin. In addition, in many cases, the tissues on the ventrum of the penis seem inelastic as the patient’s penis is examined on stretch. This palpable inelasticity on the ventral penis consists of dysgenetic tissue, which can replace the Buck and dartos fascia layers; and in some cases, there is an element of inelasticity of the tunica itself.

During surgical exploration, Devine and Pepe obtained tissue from these patients for evaluation of 5α-reductase levels. Those data suggested a deficiency of the enzyme in the ventral dysgenetic tissue. The values were inconclusive at the time and the study was discontinued. El-Galley and colleagues (1997) also looked for growth factor deficiency in tissues of males with hypospadias and found a correlation. To our knowledge, however, a growth factor analysis has not been undertaken in patients with chordee without hypospadias.

An important part of the preoperative evaluation is the submission of instant or digital photographs of the erect penis, taken by the patient, documenting the curvature. The photographs are especially helpful in differentiating between the patients we refer to as having chordee without hypospadias and those with congenital curvatures of the penis. In a patient who has chordee without hypospadias, the photograph reveals an erect penis commensurate with the size of the detumesced penis, whereas in the congenital curvature patient, the erect penis is noticeably large. It is important to address the psychologic aspects of the condition as an integral part of the treatment, and many of our patients will see a psychologist preoperatively. Corrective surgery for chordee without hypospadias is highly successful, and, in almost all cases, an effective correction can be accomplished with a single operation (Devine et al, 1991). In some cases, the penis has been straightened by excision of all the dysgenetic tissues from the ventral side of the penis and wide mobilization of the corpus spongiosum from the glans penis into the perineum.

Even in patients with obvious abnormalities of the corpus spongiosum (i.e., poor ventral fusion or frank bifid corpus spongiosum), wide mobilization usually reveals that it is not the corpus spongiosum that remains as the ventral limiting factor. In most patients, the penis remains curved because of the inelasticity of the ventral aspect of the corpora cavernosa themselves. Furthermore, in an occasional patient, the corpus spongiosum becomes atretic distal on the shaft, and the urethra itself is only an epithelium-lined tube. Even in these patients, with wide mobilization of the epithelial distal portion and elevation of the proximal corpus spongiosum, it is unusual to find the corpus spongiosum or the epithelial tube limiting the ventral erection. If the epithelial tube has served as an adequate urethra (i.e., it is not stenotic), the morbidity of urethral division and subsequent need for urethral reconstruction must be considered before such a procedure is undertaken. Because the evolution of hypospadias repairs accomplished by wide mobilization of the corpus spongiosum and epithelial and corpus spongiosal elements distal to the meatus has allowed onlay procedures, the morbidities of urethral division must be strongly considered and, we believe, usually avoided.

In children, after mobilization and excision of the dysgenetic tissues, the residual chordee can usually be corrected by making a longitudinal incision, with a sharp blade, in the ventral midline of the corpora cavernosa while an artificial erection is maintained. The incision (midline ventral septotomy) can often be extended between the corporeal bodies for a significant distance, allowing the edges of the ventral tunica to move laterally. The penis will noticeably straighten with erection.

If this maneuver is not sufficient, the dorsal neurovascular structures can be mobilized in concert with Buck fascia, and a small ellipse or ellipses of dorsal tunica albuginea can be excised and closed with watertight plicating sutures. Caution is important, however, when the dorsal neurovascular structures are mobilized; with poor development of the ventral structures, which occurs in some patients, the arborization of the dorsal arteries provides the dominant vascularity to the glans.

Congenital Curvatures of the Penis

Patients with congenital curvature of the penis can have ventral, lateral (which is most often to the left), or, unusually, dorsal curvature. Photographs of the erect penis demonstrate a smooth curvature that generally involves the entire pendulous portion of the penile shaft.

Patients usually present as otherwise healthy young men between the ages of 18 and 30 years. Many of these patients have noticed curvature before passing through puberty but have presumed it to be normal. With puberty, however, they discover that the curvature is not normal, or they become sexually active and discover that the curvature impedes their efforts, or they notice increasing curvature as they pass through puberty, and this, in their minds, clearly would preclude sexual intercourse. On occasion, a patient waits until he is older than 30 years to deal with the anomaly, and, even less often, there is a younger adolescent, who is able to discuss his genitalia with his parents.

In circumcised patients, we make an incision through the circumcision scar, which in many cases is displaced well down on the penile shaft. Even with relatively significant displacement of the circumcision scar on the shaft of the penis, however, the reincision should be through the circumcision scar. The penis is then degloved by dissection of the layer immediately superficial to the superficial lamina of Buck fascia.

An artificial erection is obtained with normal saline while others use pharmacologic agents. We do not routinely recommend a tourniquet device, because constricting devices can conceal the proximal limits of the curvature. This is of most significance in cases of ventral curvatures, which frequently extend proximally. On occasion, some element of perineal pressure is initially required, but these are patients with normal erectile function, and their venous occlusive function is normal. The artificial erection demonstrates the character of the curvature and the location of maximal curvature. In patients with ventral curvature, there may be some illusion of thickening of the dartos and Buck fascia, and in those patients, the fibrous tissue is mobilized and completely excised. The corpus spongiosum is detached from the corpora cavernosa and mobilized from the glans to the penoscrotal junction.

After these tissues are excised, the artificial erection is repeated, and an occasional patient is found to have been completely straightened. Most patients, however, suffer from a differential elasticity between the dorsal and the ventral aspects of the corporeal bodies, and although the curvature may have been lessened, it persists unless further procedures are done to straighten the penis.

In the adult patient with persistent curvature, there are two options for surgical correction: (1) to lengthen the ventral aspect of the penis by making transverse incisions in the ventral tunica and placing an autologous tissue graft (we currently use the small intestinal submucosal graft at our institution), and (2) to shorten the dorsal aspect of the penis by elevating the neurovascular bundle, excising an ellipse or ellipses from the dorsum of the tunica albuginea, and closing the defects in watertight fashion (Nesbit [1965] procedure). Because the size of the erect penis is usually not a problem in these cases of congenital curvature, we have chosen the second option and are strenuously against ventral grafting. The recovery period after this procedure is much shorter, and the variabilities of graft take do not have to be considered. In addition, when a graft is used, there is always the possibility, although uncommon, of the development of graft-induced veno-occlusive dysfunction. In a 2000 consensus conference sanctioned by the World Health Organization, the committee on Peyronie disease and congenital curvature of the penis agreed that the majority of, if not all, cases in men with the classic finding of congenital curvature of the penis were best managed with a plication or corporoplasty techniques but not grafting techniques (Jardin et al, 2000; Lue, 2004). This consensus was reiterated at the next World Health Organization conference. It is therefore preferable to shorten the longer aspect of the penis in patients with congenital curvature. However, if the patient falls into the category of chordee without hypospadias and shortness of the penis is an issue, we selectively use incisions with grafts to correct the curvature (Devine and Horton, 1975).

After the decision has been made to proceed with excisions of ellipses of dorsal tunica, the Buck fascia can be elevated, in concert with the dorsal neurovascular structures, by beginning just lateral to the corpus spongiosum and carrying the dissection dorsally across the midline. Alternatively, the tunica can be exposed by excising the deep dorsal vein of the penis and opening the inner lamina of the Buck fascia. Elevation of the neurovascular structures is done by dissecting from the dorsal midline laterally around to the corpus spongiosum and from the coronal margin to the penopubic junction, thus limiting the effects of stretching the dorsal structures with exposure of the dorsum of the penis.

An artificial erection is obtained to plan the proposed ellipse excisions. We prefer to use several small ellipses rather than try to correct the curvature with one large ellipse. The first ellipse is usually positioned at the point of maximal concavity. The edges of the planned ellipse are then apposed with a Prolene suture. The artificial erection is repeated to assess the effects of that excision. If there is good straightening in that area of the shaft, the incisions are again well marked, the plicating sutures are removed, and the ellipses of tunica are made with a sharp scalpel blade. By dissection in the space of Smith and removal of only an ellipse of tunica, the ellipses are carefully excised to avoid damage to the underlying erectile tissue or can be merely closed under the reapproximated edge of the defect in the tunica albuginea. The edge of the ellipse is reapproximated with a combination of interrupted 4-0 polydioxanone sutures and a watertight running 4-0 polydioxanone suture.

After closure, we repeat the artificial erection to assess the results of the first ellipse with the others. A final artificial erection should demonstrate the penis to be perfectly straight. In cases of ventral curvature, or when complex curvatures are associated with an element of ventral curvature, a minimal degree of dorsal curvature after correction is acceptable. In most cases, as the sutures dissolve, the penis either remains minimally dorsiflexed or becomes perfectly straight.

The Buck fascia is closed. Two small suction drains are placed superficial to the Buck fascia but deep to the dartos fascia. We then replace the skin sleeve, with its edges apposed with interrupted small Vicryl or Monocryl sutures. In all patients, we place a small Foley catheter, which is removed on the first postoperative day. The two small suction drains are also removed at 12 to 24 hours. Depending on the amount of edema and drainage, patients are discharged from the hospital on the evening of the first or early the second postoperative day.

A congenital lateral curvature of the penis is often associated with some complexity of curvature; patients frequently notice lateral curvature in association with a ventral or, less commonly, a dorsal curvature. However, some patients present with only lateral curvature, with the right side larger than the left, and curvature to the left.

In some cases, a repair of the lateral curvature can be approached through a small incision at the point of maximal curvature. Laterally placed incisions on the penile shaft are not cosmetically optimal. We prefer, however, a degloving incision after exposure of the deep penile structures; the point of maximal concavity is then marked. Prolene sutures are placed, and an artificial erection is again performed. The size of the ellipse is then assessed, and the ellipse is excised and closed as discussed earlier.

As mentioned, however, most cases of lateral curvature are associated with complex curvatures. In these patients, the correction of the curvature is similar to that described for patients with ventral curvature, by a circumcising incision with the skin reflected. In contrast to a ventral curvature, however, with a lateral curvature, the entire dorsal neurovascular bundle does not need to be reflected; therefore, it is seldom required, nor is it considered beneficial, to excise the deep dorsal vein in approaching the dorsum of the penis. The postoperative care is the same as described for a ventral curvature.

For the uncommon patient with a congenital dorsal curvature of the penis, the repair is best accomplished by mobilizing the lateral aspect of the corpus spongiosum to allow small ellipses lateral to the midline to be positioned on the ventrum of the penis, by the technique described before. Again, postoperative care is as described for a ventral curvature.

Although described as a method for plication for curvature associated with Peyronie disease, corporoplasty, the procedure described by Yachia (1993), is also useful for the correction of congenital curvatures. The procedure essentially consists of longitudinal incisions in the tunica albuginea with transverse closure. Thus the “long side” is plicated without the need for excision; however, the plication is durable in that the tunica is opened and closed with a resulting scar, rather than reliance only on the strength of sutures as originally described by Nesbit (1965). With this technique, closure is done with absorbable monofilament suture.

Acquired Curvatures of the Penis

Acquired curvatures of the penis inevitably follow trauma to the penis. Many of these cases are associated with Peyronie disease, also believed to be associated with trauma to the penis during intercourse (Bella et al, 2007). An occasional patient also presents who has had vigorous internal urethrotomy, with the incision extended outside the urethra and corpus spongiosum, and involving the tunica of the corporeal bodies, causing scarring that is significant enough to be associated with curvature.

Acquired Curvatures of the Penis That Are Not Peyronie Disease

When a young man presents with an acquired curvature of the penis, one must always consider Peyronie disease. However, many will not have true Peyronie disease. These patients, on close questioning, reveal a history of minimal lateral curvature of the penis and a clear memory of a lateral buckling injury that occurred during intercourse. In some cases, the patient remembers hearing a “snap” and notices immediate detumescence and significant ecchymosis of the penis. These patients are often referred with a diagnosis of Peyronie disease, but a diagnosis of curvature secondary to penile fracture is more accurate. Because of the noticeable events associated with fracture of the penis, many patients present acutely, and reconstruction can be accomplished at that time.

On occasion, however, a patient or his initial-care physician ignores the stigmata of the trauma (often described as “minimal” by patients), and the patient presents with a noticeable lateral scar that causes both indentation of the lateral aspect of the penis and, in some cases, curvature. Patients who had preexisting lateral curvature may actually notice that their penis has been straightened by the trauma, but they are disturbed by the concavity caused by the scar. In others, the small linear scar causes a significant lateral curvature.

Another group of patients presents after a similar buckling trauma to the penis but without associated detumescence or ecchymosis. These patients report noticing that their erections were painful for a period after the trauma, and then a nodule developed in the lateral aspect of the penis. Eventually, they present with a lateral linear scar that has led to curvature and indentation at the site. We refer to this injury as a subclinical fracture of the penis.

The lesion of a subclinical fracture of the penis is believed to be due to the disruption of the outer longitudinal layer of the tunica albuginea during the buckling trauma. The inner, circular layer is not disrupted, however, and maintains the blood-tight continuity of the corpus spongiosum. Another possible scenario is that both layers of the tunica albuginea are disrupted but the overlying Buck fascia maintains its integrity. There are also patients who notice a pop with intercourse and a period of pain with erections, followed by curvature of the penis—usually dorsal. These patients probably tear the septal insertion completely. These patients clearly behave more like Peyronie disease patients.

Patients usually have normal erectile function after subclinical or clinical fracture of the penis; there appears not to be an association with concomitant global cavernosal veno-occlusive dysfunction. However, the association of cavernosal veno-occlusive dysfunction and trauma of the penis continues to be seen, and some patients have significant problems with erectile dysfunction after fracture-type injuries of the penis. These injuries are not associated with shortening of the penis. In most cases, it is the lack of erectile dysfunction and penile shortening that help distinguish these patients from Peyronie disease patients. If a detailed history leads one to suspect blighted erectile function, an evaluation of erectile function should be accomplished before proceeding with surgery. At our institution, we evaluate these patients with duplex ultrasonography and selectively with dynamic infusion cavernosometry and cavernosography.

Although foreshortening of the penis is not a characteristic of either the injury itself or the resulting scar in either of these injuries, these patients are not thought to be best treated by approaching the opposite aspect of the scar and excising an ellipse of the tunica. This would result in bilateral scars, which would cause bilateral indentations of the penis, and although the penis would have been straightened by the correction, most patients are upset by the cosmetic and functional result of a near-circumferential indentation of the penis. Instead, we excise the scar and place a graft to replace the corporotomy defect caused by the scar excision. Because these scars are on the lateral aspect of the penis, minimal mobilization of Buck fascia, associated dorsal neurovascular structures, and corpus spongiosum is required at the site.

The results of the surgical correction described have been extremely effective. All such patients treated at the authors’ institution have been successfully corrected with a single operation.

Key Points: Curvatures of the Penis

Total Penile Reconstruction

General

The principal techniques of penile reconstruction were originally developed for treatment of trauma patients, and, in many cases, these patients were victims of war injuries. In 1936, Bogaraz described a technique for phallic construction in a series of war-injured patients, and in 1944, Frumkin followed with a series from the Soviet Union. Aware of the work in the Soviet Union, Gillies and Harrison (1948) reported on a series of patients in whom they had accomplished penile reconstruction while stationed at a major hospital in the outskirts of London during World War II. In this series, there were a number of patients with a complete absence of the penis.

Initially, all procedures for phallic construction involved delayed formation and transfer of tubed abdominal flaps. These tubes were produced from random flaps of skin and because of their size were based on a tenuous blood supply. To allow new vascular patterns to become established in the transferred tissue, they were formed in stages, with a “delay” between the stages. In the “tube-within-a-tube” design, the inner tube allowed the placement of a baculum during intercourse, and the outer tube provided skin coverage. Patients voided through a proximal urethrostomy. This continued to be the “state-of-the-art” phallic construction and penile reconstruction until 1972, when Orticochea described total reconstruction of the penis using the gracilis musculocutaneous flap. In 1978, Puckett and Montie reported a series in which they constructed the penis with a tubed groin flap. In the early cases in this series, the flap was transferred in delayed fashion to the area of the penile stump. Later in the series, a microvascular free-transfer technique was employed.

In 1984, Chang and Hwang popularized the forearm flap, based on the radial artery, for phallic construction. Biemer (1988) reported a modification of the forearm flap, which was also based on the radial artery; and, in 1990, Farrow and colleagues reported their “cricket bat” modification of the radial forearm flap. Today, forearm flaps are the most commonly employed method for total phallic construction and penile reconstruction.

The forearm flap is usually harvested from the nondominant forearm. Preoperatively, the Allen test is used to screen patients carefully for arterial insufficiency. This test involves palpation of the radial and ulnar arteries in the wrist, with the patient making a tight fist to express blood from his hand. As he opens his hand, the fingers are pale, but if palmar circulation is normal and both arteries are patent, the fingers turn pink when one of the arteries is released. If, on the basis of either the Allen test or the patient’s history, there is any doubt about the integrity of the radial and ulnar arteries or the palmar arch, upper extremity angiography is performed.

As described, the forearm flap is a fasciocutaneous flap vascularized by the radial artery; however, the ulnar artery also vascularizes the forearm fascia and most of the forearm skin. The radial artery arises as a continuation of the brachial artery and proximally lies beneath the belly of the brachioradialis muscle, becoming more superficial at the wrist. The ulnar artery is also a continuation of the brachial artery and vascularizes a similar area of skin and underlying adipose tissue. The vascularity of the overlying skin is achieved by way of the underlying (antebrachial) fascia, which is the superficial fascia investing the musculature of the forearm.

The forearm flap can be elevated and transferred on the superficial fascia. The lateral and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves appear proximally beneath the fascia. The cephalic, basilic, and medial antebrachial veins are also included in the flap and constitute a portion of the venous drainage. In some patients, the vena comitans is the dominant venous drainage system. At the time of flap transfer, it is imperative to assess both the venous comitans and the superficial veins to determine which is the dominant system in the individual patient.

The various modifications of the forearm flap do not represent changes in the technique of flap elevation; rather, they are modifications in the design of the skin island and the relative position of the urethral paddle in relation to the skin that will eventually become shaft coverage. Each of these modifications has advantages in different situations.

In the forearm flap as described by Chang and Hwang (1984), the shaft is covered with the radial aspect of the skin paddle. A de-epithelialized strip is made, and a second skin island, on the ulnar aspect of the skin paddle, is tubed to form the urethra. The urethral tube is then rolled within the tube of skin to form a tube-within-a-tube design. In the white population, this flap has demonstrated a tendency to lead to ischemic stenosis of the lateral paddle, where the urethra is constructed.

In the cricket bat modification, the urethral tube extends distally, closely overlying either the radial or the ulnar artery. We have experience with elevation of the cricket bat modification on both arteries. Proximal to the urethral strip, a broader portion of the skin paddle provides coverage of the shaft. The urethral portion is tubed and transposed by inverting it into the center of the shaft portion of the skin paddle. The advantage of this modification lies in centering the urethral portion over the respective artery, in contrast to the Chinese design, in which the ulnar aspect is far distal from the radial artery, with the potential for ischemic stenosis or loss of that portion. The cricket bat modification has been useful in trauma patients, particularly in those who have a significant stump of erectile bodies and urethra left after the injury.

The modification by Biemer (1988) also centers the urethral portion of the flap over the artery. As described by Biemer, the flap is elevated on the radial artery and includes a vascularized piece of the radial bone intended to provide rigidity to the new penis. The inclusion of cartilage and bone has not been universally successful, however, and rigidity in these flaps is obtainable by the use of either an externally applied or internally implanted prosthesis. If the bone is not elevated, the Biemer flap design can be elevated on either the radial or the ulnar artery. At our center, we most often elevate the flap on the ulnar artery, in a modification of the Biemer design.

Modifications of the Biemer design also include the glans construction technique that was originally described by Puckett and Montie (1978). In the original Biemer design, a central strip becomes the urethra, and lateral to that strip, two de-epithelialized portions and two lateral islands (lateral aspects of that skin paddle) are fused dorsally and ventrally to cover the shaft. With the modification of Puckett and colleagues (1982), a large island is left distally and flared back over the tip of the tubed flaps, creating the illusion of a glans penis. The Biemer design, especially when it is combined with Puckett’s design for glanular construction, offers the best cosmetic results (Fig. 36–40).

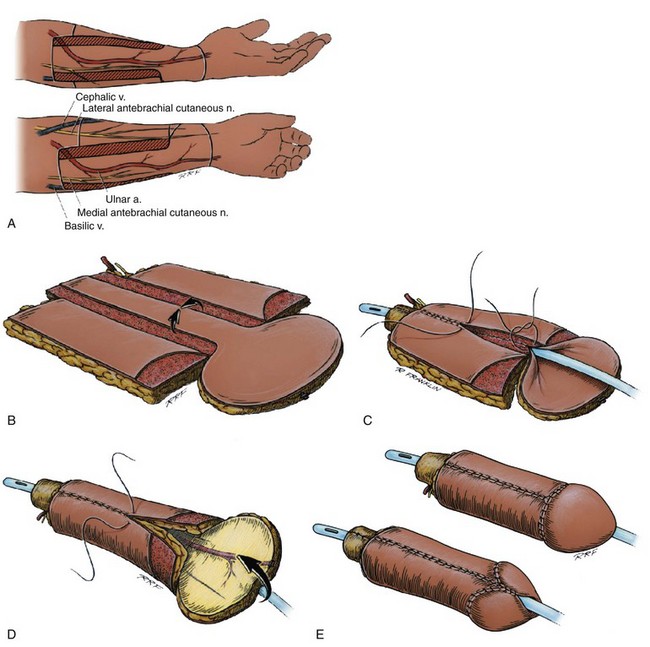

Figure 36–40 A, Schematic diagram of an ulnar forearm flap, modified Biemer design, on the patient’s left (usually nondominant) forearm. B, Schematic of the elevated flap. Notice the flap has been divided into skin islands by de-epithelializing the strips. Laterally are the shaft skin islands, medially is the urethral skin island, and distally is the intergral glans, after the design of Puckett. C, Schematic of the configuration of the flap. Notice the urethral skin island has been tabularized to the level of the neomeatus. The lateral shaft skin islands are now in the process of being tabularized over the tabularized urethra. D, Schematic of the phallic flap as it is further configured, this view is of the dorsum. Notice the venral skin island has been closed over the urethra, the dorsal skin islands are being collected. The integral glans will then be reflected over the dorsum of the flap. E, The drawing of the appearance of the phallus after it is totally configured and transposed to the area of the “penis.”

There are several disadvantages to the use of a forearm flap for phallic construction. The major disadvantage of forearm flaps is the obvious donor site deformity. We have reconstructed the donor site with full-thickness skin grafts taken from the area of the inguinal crease, and the cosmetic result is far superior to that obtained when the donor site is reconstructed with split-thickness skin (even thick split-thickness skin). A second disadvantage lies in the possibility of the development of cold intolerance in the hand of the donor side. Early in our experience with the forearm flap, we reconstructed the radial artery with an interposition vein graft. We have since abandoned this procedure in the majority of our series and have not seen cold intolerance in our patients. Another disadvantage occurs in both male and virilized transgender patients when the forearm skin is hirsute, because the hair can be problematic if it is included in the portion of the flap used for urethral construction. In such patients, we try to identify the potential for the problem and refer them for epilation before surgery.

McRoberts and Sadove (2002) proposed the use of the fibular osteocutaneous flap for phallic construction. The fibula is elevated on the periosteal vessel along with the overlying skin paddle. As they described, urethral reconstruction is by tubed graft techniques, and their procedure had a 100% urethral complication rate. The center from Munich has proposed use of this flap with a prefabricated urethra. They place a tubed graft initially in the center of the paddle while it is still on the leg, then elevate the flap later and attach the urethra. We do not agree with the presumption that these tubed grafted urethras would behave differently; however, the surgeons in Munich propose the technique as a better one. For patients who only need vascularized tissue to cover the shaft of the penis, we have used the upper lateral arm flap. This is a fasciocutaneous flap, and its cutaneous vascular territory is centered on the radial collateral artery. The skin of the lateral upper arm is thin, with little subcutaneous adiposity. To mark the location of the lateral intramuscular septum and the course of the superior radial collateral artery, we draw a line joining the insertion of the deltoid with the lateral epicondyle. We begin the dissection posteriorly, elevating the superficial fascia until the posterior lateral portion of the intramuscular septum has been identified. A potential disadvantage of this flap lies in the fact that the entire venous drainage is dependent on the vena comitans, and although superficial veins do traverse the flap, none of them seems to provide significant venous drainage. Although this is disquieting, we have found the flap to be completely reliable thus far, with no losses due to venous insufficiency.

This flap has also been used for total phallic construction. For this purpose, the flap is expanded by tissue expander and elevated across the elbow, and the distal flap is elevated on the recurrent radial artery. As with the forearm flap, the donor site of an upper lateral arm flap can be disfiguring. However, because the scar is on the upper arm, it is more easily concealed beneath a shirtsleeve than a scar in the forearm. All the flaps described allow microneurosurgical coaptation of the flap cutaneous nerves with recipient nerves. With total phallic construction, the cutaneous nerves can be attached either to the dorsal nerves of the penis or to the dorsal nerves of the clitoris in the transsexual patient. When these nerves are not available, the nerves can be coapted to the pudendal nerve, which in most patients requires an interposition graft. These nerves are thought to provide the best restoration of erogenous cutaneous sensibility. We have also coapted the flap’s cutaneous nerves to the ilioinguinal nerves, which provides sensation to the inner aspect of the thigh and the lateral aspect of the scrotum, and have achieved a reasonable degree of erogenous sensibility.

In most patients, the deep inferior epigastric vessels are the recipient vasculature for flap transfer. These vessels are medial branches of the iliac system and lie on the dorsal (deep) aspect of the rectus abdominis muscle. The artery usually remains deep to the muscle, although an early penetration of the artery into the muscle can be observed in some patients. The artery classically bifurcates at the level of the umbilicus and is generally accompanied by two or more venae comitantes. These vessels have been elevated by several methods, and Lund and colleagues (1995) described their elevation for penile revascularization with laparoscopic techniques. When the deep inferior epigastric vessels are used, it is often necessary to also include a saphenous vein for further venous runoff.

In some patients, however, these vessels are not available, and we have used a saphenous interposition graft to the superficial femoral artery. With use of this technique, we mobilize the saphenous vein well down the upper aspect of the thigh and then attach the vein to the femoral artery, making a temporary arteriovenous fistula. The fistula is divided, with the saphenous vein becoming the venous runoff and the interposition graft providing the arterial inflow. This system of recipient vessels is greatly inferior to a direct arterial anastomosis. Because of this, in a few patients we have divided the profunda femoris vessel and vigorously dissected it from its other branches. We have then done an end-to-end (artery-to-artery) anastomosis of the ulnar artery to the profunda femoris. However, the long-term consequences to the patient of dividing the profunda femoris are not clear. Immediate reconstruction of the profunda does not appear to be advantageous, as the dissection required to mobilize the profunda femoris to become a recipient vessel requires the division of a number of proximal branches, and these would not be reconstructed with an immediate reconstruction of the profunda femoris. Mention of this as a potential means of “creating” recipient vessels is not to recommend the procedure, because the procedure may yet have unacceptable long-term consequences. Another option in extreme cases is to use the superficial femoral, which could be reconstructed with a vein interposition. When the “classic” recipient vessels are not available, these other methods may be acceptable. However, we strenuously caution concerning their use, because the long-term consequences are not known. We currently believe that division of the superficial femoral artery with immediate reconstruction is the better of these choices.

In the latter part of our series, we included the routine transfer of gracilis muscle to cover the area of the urethral anastomosis, increasing the vascularity to that area and significantly altering the incidence of anastomotic fistula and stricture formation. We have also elevated a bipedicled flap from the area of the penile shaft base, which is transposed beneath the phallic flap. This flap provides increased bulk and some modicum of scrotal construction, and when it is combined with the gracilis muscle, its thickness provides excellent coverage for the juncture of the flap with the base of the neoscrotum. Mobilization of a tunica dartos flap with tunica vaginalis pedicle, or a Martius flap in the transgender patient, may obviate the necessity to elevate and transpose a gracilis muscle flap.

During the phallic construction procedure, urine is diverted by means of a suprapubic cystostomy tube, and the urethra is stented with a No. 14 soft silicone (Silastic) catheter. A voiding study is usually performed between the third and fourth postoperative week.

Rigidity for intercourse in the patient with phallic construction is usually achieved by either an externally applied or a permanently implanted prosthesis. Prosthetic implantation is never undertaken until 1 year after phallic construction, because protective sensibility must be demonstrated in the flap. When the flap is transferred, it is, by definition, rendered insensate. At about 3 to 4 months after reconstruction, however, as nerve regeneration occurs, sensation becomes noticeable. In addition, before prosthetic implantation is undertaken, the urethra must be patent and proved to be durable.

At our center, we now have a large series of patients with internally implanted devices. We have implanted both hydraulic and articulated prostheses encased in Gore-Tex neocorpora. These devices are anchored to the ischial tuberosity and the pubis by anchoring the neocorpora to these bone structures. In most patients, we implant two cylinders or rods. Early in our series, we had problems with hematoma and seroma formation and subsequent infection. However, since modifying our antibiotic regimen and including the routine use of suction drains with the implant procedure, we have had excellent success with implantation. We currently place the antibiotic-coated (Inhibizone) AMS 700CXR.* The Titan prosthesis with hydrophilic coating and narrow base has also been used.

We also have implanted testicular prostheses in a number of patients. In patients in whom we have used a hydraulic device, we have implanted the pump in one neohemiscrotum and a testicular prosthesis in the opposite one.

Reconstruction after Trauma

In many ways, the problems of trauma patients are more challenging to solve than are those of patients who require total phallic construction. We have treated a large number of patients who have had devastating injuries to the penis after complicated prosthetic surgery or surgery to correct penile curvatures of Peyronie disease. The goal in these patients is to preserve the penile structures and function as much as possible, yet correct the deficiencies that are imposed on the patient by the trauma.

Acutely, urine must be diverted, necrotic tissue must be carefully debrided, and any foreign bodies that may have been implanted must be removed. Vigorous acute wound management stabilizes the wounds and allows active granulation to progress. In all trauma patients, an attempt should be made to save as many of the penile structures as possible.

Approximately 3 to 6 weeks after trauma, primary reconstruction can be undertaken, although we have elected to wait 4 to 6 months in some patients, depending on the situation. When significant adjacent tissue loss has occurred, the adjacent areas must be well reconstructed before proceeding with either phallic construction or penile reconstruction.

In the trauma patient, it is imperative that well-vascularized tissues be eventually transposed to the adjacent area, and reconstruction of these areas can be accomplished with a number of flaps. For groin reconstruction, the tensor fascia lata flap has been useful. The rectus femoris flap, characteristically long and large, can be transposed to the area of the lower abdomen and has been an extremely useful flap for inguinal and lower abdominal reconstruction. The gracilis muscle is an excellent flap for reconstruction of the perineum and the groin. Alternatively, the posterior thigh flap can be used for reconstruction of the groin and perineum and, in some cases, transposed to the lowermost portion of the lower abdomen. The rectus abdominis flap is a useful flap and can be elevated with a vertical or transverse skin paddle. In addition, the flap can be transposed to either the ipsilateral or contralateral side. Care must be taken in the patient who has had lower abdominal external beam irradiation.

Variations of the flap designs described for complete phallic construction have been successfully applied in select patients for penile reconstruction. An example is seen in one patient who suffered an injury to his penis from a shotgun blast. The blast injured a large portion of the patient’s right corpus cavernosum, and the majority of the penile skin was either destroyed or used for urethral reconstruction. In this patient, a flap based on the Chinese design was elevated. However, because the urethral reconstruction was accomplished with a penile skin island, the ulnar portion of the flap was not needed for that purpose. Therefore the ulnar portion was de-epithelialized and tubularized to form bulk and a new right corporeal body. This patient is now sexually active, and the bulk of the tube’s dermal section gives adequate support to his penis for intercourse.

Another patient required only distal urethral construction and glans reconstruction. For this patient, we based a flap on the Biemer design to construct a glans. The proximal portions of the flap were de-epithelialized, allowing fixation of the neoglans on the tips of the corporeal bodies, and an excellent functional and cosmetic result was achieved for this patient. The versatility of free-flap technology allows the solution of complex issues with reasonably acceptable functional and cosmetic results.

Female-To-Male Transsexualism

Female-to-male transsexual patients present a unique challenge, and no patient should be considered for definitive reassignment surgery without having undergone complex screening and evaluation by a team consisting of mental health professionals, as well as surgeons who are skilled in undertaking transgender surgery. It is imperative that an ongoing, stable, therapeutic relationship be established between the patient and a mental health professional at the time of definitive gender reassignment surgery. At our institution, the Harry Benjamin criteria (Ramsey, 1996) are strictly adhered to, and surgery is accomplished by a team of urologists, plastic surgeons, and gynecologists.

In most patients, the first stage of female-to-male transsexual surgery consists of bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, hysterectomy, vaginectomy, and urethral lengthening with colpocleisis. Even in the virginal patient, our surgeons have become skilled at accomplishing a hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy by way of transvaginal surgery. We perform a vaginectomy at the same operation, leaving the anterior vaginal wall to be transposed as a random flap to lengthen the female urethra and allow colpocleisis. Lengthening of the female urethra brings the base of the native urethra up to what will be the base of the phallic flap; along with the transfer of gracilis muscle, it has significantly altered our surgical results with regard to urethral anastomotic fistula and stricture. Urine is diverted with a suprapubic tube, and a voiding trial is performed in approximately 21 days. Patients are generally in the hospital for 2 to 3 days and return 3 to 4 months later for phallic construction.

For phallic construction in the transsexual patient, we elevate a bipedicled flap of skin, as already described, from the area where the phallic structure will be implanted and transpose it to the undersurface of the neopenis. The patient is generally in the hospital for a period of 10 to 14 days after total phallic construction, and a voiding trial with contrast material is done at about 28 days postoperatively. After 1 year, when erogenous sensibility is demonstrated and the urethra is proved to be durable, prosthetic implantation is considered.

Key Points: Total Penile Reconstruction

Aboseif SR, Breza J, Lue TF, Tanagho EA. Penile venous drainage in erectile dysfunction: anatomical, radiological and functional considerations. Br J Urol. 1989;64:183-190.

Akporiaye LE, Jordan GH, Devine CJJr. Balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO). AUA Update Series. 1997;16:166-167.

Chapple CR, Pang D. Contemporary management of urethral trauma and the post-traumatic stricture. Curr Opin Urol. 1999;9:253-260.

Chapple C, Barbagli G, Jordan G, et al. Consensus statement on urethral trauma. BJU Int. 2004;93:1195-1202.

Coursey JW, Morey AF, McAninch JW, et al. Erectile function after anterior urethroplasty. J Urol. 2001;166:2273-2276.

Devine CJJr, Blackley SK, Horton CE, Gilbert DA. The surgical treatment of chordee without hypospadias in men. J Urol. 1991;146:325-329.

Fichtner J, Filipas D, Fisch M, et al. Long-term outcome of ventral buccal mucosa onlay graft urethroplasty for urethral stricture repair. Urology. 2004;64:648-650.

Heyns CF, Steenkamp JW, de Kock ML, Whitaker P. Treatment of male urethral strictures: is repeated dilation or internal urethrotomy useful? J Urol. 1998;160:356-358.

Iselin CE, Webster GD. The significance of the open bladder neck associated with pelvic fracture urethral distraction defects. J Urol. 1999;162:34-51.

Jordan GH. The application of tissue transfer techniques in urologic surgery. In: Webster G, Kirby R, King Let al, editors. Reconstructive urology. Oxford (UK): Blackwell Scientific; 1993:143-169.

Levine J, Wessells H. Comparison of open and endoscopic treatment of posttraumatic posterior urethral strictures. World J Surg. 2001;25:1597-1601.

McCallum RW, Colapinto V. The role of urethrography in urethral disease. Part I. Accurate radiological localization of the membranous urethra and distal sphincters in normal male subjects. J Urol. 1979;122:607-611.

McCallum RW, Colapinto V. The role of urethrography in urethral disease. Part II. Indications for transsphincter urethroplasty in patients with primary bulbous strictures. J Urol. 1979;122:612-618.

McRoberts JW, Chapman WH, Answell JS. Primary anastomosis of the traumatically amputated penis: case report and summary of literature. J Urol. 1968;100:751-754.

Morey AF, Metro MJ, Carney KJ, et al. Consensus on genitourinary trauma: external genitalia. BJU Int. 2004;94:507-515.

Pansadoro V, Emiliozzi P. Internal urethrotomy in the management of anterior urethral strictures: long-term followup. J Urol. 1996;156:73-75.

Quartey JK. One stage penile/preputial cutaneous island flap urethroplasty for urethral stricture: a preliminary report. J Urol. 1983;129:284-287.

Rourke KF, McCammon KA, Sumfest JM, et al. Open reconstruction of pediatric and adolescent urethral strictures: long-term follow-up. J Urol. 2003;169:1818-1821. discussion 1821

Webster GD, Mathes GL, Selli C. Prostatomembranous urethral injuries: a review of the literature and a rational approach to their management. J Urol. 1983;130:898-902.

Aboseif SR, Breza J, Lue TF, Tanagho EA. Penile venous drainage in erectile dysfunction: anatomical, radiological and functional considerations. Br J Urol. 1989;64:183-190.

Akporiaye LE, Jordan GH, Devine JrCJ. Balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO). AUA Update Series. 1997;16:166-167.

Albers P, Fichtner J, Bruhl P, Muller SC. Long-term results of internal urethrotomy. J Urol. 1996;156:1611-1614.

Allen JS, Summers JL. Meatal stenosis in children. J Urol. 1974;112:526-527.

Andrich DE, Mundy AR. The nature of urethral injury in cases of pelvic fracture urethral trauma. J Urol. 2001;165:1492-1495.

Andrich DE, O’Malley KJ, Summerton DJ, et al. The type of urethroplasty for a pelvic fracture urethral distraction defect cannot be predicted preoperatively. J Urol. 2003;170(Pt. 1):464-467.

Anger JT, Raj GV, Delvecchio FC, Webster GD. Anastomotic contracture and incontinence after radical prostatectomy: a graded approach to management. J Urol. 2005;173:1143-1146.

Angermeier KW, Jordan GH. Complications of the exaggerated lithotomy position: a review of 177 cases. J Urol. 1994;151:866-868.

Armenakas NA, Morey AF, McAninch JW. Reconstruction of resistant strictures of the fossa navicularis and meatus. J Urol. 1998;160:359-363.

Ashken MH, Coulange C, Milroy EJ, et al. European experience with the urethral Wallstent for urethral strictures. Eur Urol. 1991;1:181.

Atala A. Experimental and clinical experience with tissue engineering techniques for urethral reconstruction. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:485-492. ix

Badlani GH, Press SM, Defalco A, et al. UroLume endourethral prosthesis for the treatment of urethral stricture disease. Long-term results of the North American Multicenter UroLume Trial. Urology. 1995;45:846-856.

Bainbridge DR, Whitaker RH, Shepheard BG. Balanitis xerotica obliterans and urinary obstruction. Br J Urol. 1971;43:487-491.

Barbagli G, Menghetti I, Azzaro F. A new urethroplasty for bulbous urethral strictures. Acta Urol Ital. 1995;9:313-317.

Barbagli G, Palminteri E, Guazzoni G. Surgical removal of urethral stents. J Urol. 1999;161(Suppl. 383):102.

Barbagli G, Palminteri E, Lazzeri M, Guazzoni G. One-stage circumferential buccal mucosa graft urethroplasty for bulbous stricture repair. Urology. 2003;61:452-455.

Barry JM. Visual urethrotomy in the management of the obliterated membranous urethra. Urol Clin North Am. 1989;16:319-324.

Bedos F, Cibert J. Urologia. La térapeutica y sus bases. Barcelona: Espaxs; 1989. p. 1122–5

Bella AJ, Sener A, Foell K, Brock GB. Nonpalpable scarring of the penile septum as a cause of erectile dysfunction: an atypical form of Peyronie’s disease. J Sex Med. 2007;4(1):226-230.

Bernard P, Prost T, Durepaire N, et al. The major cicatricial pempigoid antigen is a 180-KD protein that shows immunologic cross-reactivity with the bullous pemphigoid antigen. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:174-179.

Bhargava S, Chapple CR. Buccal mucosal urethroplasty: is it the new gold standard? BJU Int. 2004;93:1191-1193.

Bhargava S, Chapple CR, Bullock AJ, et al. Tissue-engineered buccal mucosa for substitution urethroplasty. BJU Int. 2004;93:807-811.

Biemer E. Penile construction by the radial arm flap. Clin Plast Surg. 1988;15:425-430.

Blandy JP, Tresidder GC. Meatoplasty. Br J Urol. 1967;39:633.

Boccon-Gibod L. Personnel communication. Laguna Nigel (CA): American Association of Genitourinary Surgeons; 2005.

Bogaraz NA. Plastic restoration of the penis. Sovet Khir. 1936;8:303-307.

Bracka A. Letter to the editor. Re: reconstruction of resistant strictures of the fossa navicularis and meatus. J Urol. 1999;162:1389.

Brandes S, Borrelli JJr. Pelvic fracture and associated urologic injuries. World J Surg. 2001;25:1578-1587.

Brandes SB, McAninch JW. Predictive factor for penile fasciocutaneous flap urethroplasty re-stricture [abstract]. Urology. 1998;9:54.

Brannen GE. Meatal reconstruction. J Urol. 1976;116:319-321.

Bryden AA, Gough DC. Traumatic urethral diverticula. BJU Int. 1999;84:885-886.

Burger RA, Muller SC, El Damanhoury H, et al. The buccal mucosal graft for urethral reconstruction: a preliminary report. J Urol. 1992;147:662-664.

Carney KJ, House J, Tillett J. Effects of DVIU and colchicine combination therapy on recurrent anterior urethral strictures [abstract 38]. J Urol. 2007;177(4):14.

Chang TS, Hwang WY. Forearm flap in one-stage reconstruction of the penis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;74:251-258.

Chapple C, Barbagli G, Jordan G, et al. Consensus statement on urethral trauma. BJU Int. 2004;93:1195-1202.

Chapple CR, Pang D. Contemporary management of urethral trauma and the post-traumatic stricture. Curr Opin Urol. 1999;9:253-260.

Chen F, Yoo JJ, Atala A. Acellular collagen matrix as a possible “off the shelf” biomaterial for urethral repair. Urology. 1999;54:407-410.

Cohen JK, Berg G, Carl GH, et al. Primary endoscopic realignment following posterior urethral disruption. J Urol. 1991;146:1548-1550.

Cohney BC. A penile flap procedure for the relief of meatal stricture. Br J Urol. 1963;35:182-183.

Cormack GC, Lamberty BG. A classification of fascio-cutaneous flaps according to their patterns of vascularization. Br J Plast Surg. 1984;37:80-87.

Coursey JW, Morey AF, McAninch JW, et al. Erectile function after anterior urethroplasty. J Urol. 2001;166:2273-2276.

Cox NH, Mitchell JNS, Morley WN. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus in non-identical female twins. Br J Dermatol. 1986;115:743-746.

Crook TJ, Koslowski M, Dyer JP, et al. A case of amyloid of the urethra and review of this rare diagnosis, its natural history and management, with reference to the literature. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2002;36:481-486.

Das K, Charles AR, Alladi A, et al. Traumatic posterior urethral disruptions in boys: experience with the perineal/perineal-transpubic approach in ten cases. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:449-454.

Datta C, Dutta SK, Chaudhuri A. Histopathological and immunological studies in a cohort of balanitis xerotica obliterans. J Indian Med Assoc. 1993;9:146-148.

Davies TO, Colen LB, Cowan N, Jordan GH. Preoperative vascular evaluation of patients with pelvic fracture uretharl distracation defects (PFUDD) [abstract 79]. J Urol. 2009;181(4):29.

DeCastro BJ, Anderson SB, Morey AF. End-to-end reconstruction of synchronous urethral strictures. J Urol. 2002;167:1389.

De Sy WA. Aesthetic repair of meatal stricture. J Urol. 1984;132:678-679.

Devine CJJr, Blackley SK, Horton CE, Gilbert DA. The surgical treatment of chordee without hypospadias in men. J Urol. 1991;146:325-329.

Devine CJJr, Franz JP, Horton CE. Evaluation and treatment of patients with failed hypospadias repair. J Urol. 1978;119:223-226.

Devine CJJr, Gonzales-Serva L, Stecker JFJr, et al. Utricular configuration in hypospadias and intersex. J Urol. 1980;123:407-411.

Devine CJJr, Horton CE. Chordee without hypospadias. J Urol. 1973;110:264-271.

Devine CJJr, Horton CE. Use of dermal graft to correct chordee. J Urol. 1975;113:56-58.

Devine PC, Fallon B, Devine CJJr. Free full thickness skin graft urethroplasty. J Urol. 1976;116:444-446.

Devine PC, Horton CE. Strictures of the male urethra, 2nd ed. Converse JM, editor. Reconstructive plastic surgery, vol. 7. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 1977, 3883-3895.

De Vocht TF, van Venrooij GE, Boon TA. Self-expanding stent insertion for urethral strictures: a 10-year follow-up. BJU Int. 2003;91:627-630.

Dillon WI, Ghassan MS. Borrelia burgdorferi DNA is undetectable by polymerase chain reaction in skin lesions of morphea, scleroderma, or lichen sclerosus et atrophicus of patients from North America. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:617-620.

Dogliotti M, Bentley-Phillips CV, Schmaman A. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus in the Bantu. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:81-85.

Doré B, Irani J, Aubert J. Carcinoma of the penis in lichen sclerosus atrophicus: a case report. Eur Urol. 1990;18:153-155.

Dounis A, Bourounis M, Mitropoulos D. Primary localized amyloidosis of the urethra. Eur Urol. 1985;11:344-345.

Dubey D, Kumar A, Mandhani A, et al. Buccal mucosal urethroplasty: a versatile technique for all urethral segments. BJU Int. 2005;95:625-629.

Duckett JW. Hypospadias techniques—update 1984. In: Standoli L, editor. Advances in hypospadias [symposium]. Rome: Acta Medica Edizione e Congressi; 1986:131-148.

Duckett JW. Hypospadias, 6th ed. Walsh PC, editor. Campbell’s urology, vol. 2. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 1992, 1914.

Duckett JW, Baskin L, Uedio K, et al. The onlay island flap hypospadias repair: extended indications. J Urol. 1993;149(Suppl.):334.

Eggleston JC, Walsh PC. Radical prostatectomy with preservation of sexual function: pathological findings in the first 100 cases. J Urol. 1985;134:1146.

El-Galley RE, Smith E, Cohen C, et al. Epidermal growth factor (EGF) and EGF receptor in hypospadias. Br J Urol. 1997;79:116-119.

El-Kassaby AW, Alla MF, Noweir A, et al. One stage anterior urethroplasty. J Urol. 1996;156:975-978.

El-Kassaby AW, El-Bialy MH, El-Halaby MR, et al. Urethroplasty using transverse penile island flap for hypospadias. J Urol. 1986;136:643-644.

El-Kassaby AW, Retik AB, Yoo JJ, Atala A. Urethral stricture repair with an off-the-shelf collagen matrix. J Urol. 2003;169:170-173. discussion 173

Elliott DS, Boone TB. Combined stent and artificial urinary sphincter for management of severe recurrent bladder neck contracture and stress incontinence after prostatectomy: a long-term evaluation. J Urol. 2001;165:413-415.

Elliott S, Metro M, McAninch J. Long-term followup of the ventrally placed buccal mucosa onlay graft in bulbar urethral reconstruction. J Urol. 2003;169:1754-1757.

Fallic ML, Faller G, Klauber GT. Balanitis xerotica obliterans in monmozygotic twins. Br J Urol. 1997;79:810.

Farrow GA, Boyd JB, Semple JL. Total reconstruction of the penis employing the “cricket bat flap” single stage forearm free graft. AUA Today. 1990;3:7.

Fichtner J, Filipas D, Fisch M, et al. Long-term outcome of ventral buccal mucosa onlay graft urethroplasty for urethral stricture repair. Urology. 2004;64:648-650.

Fisch M. Open reconstruction for recurrent anastomotic stricture after prostatectomy via retropubic and perineal approach, Abstract at Society Pelvic Surgeons Meeting, Nashville, TN, October 24, 2009.

Flynn BJ, Delvecchio FC, Webster GD. Perineal repair of pelvic fracture urethral distraction defects: experience in 120 patients during the last 10 years. J Urol. 2003;170:1877-1880.

Follis HW, Koch MO, McDougal WS. Immediate management of prostatomembranous urethral disruptions. J Urol. 1992;147:1259-1262.

Freeman C, Laymon CW. Balanitis xerotica obliterans. Arch Dermatol Syphilol. 1941;44:547-561.

Friedrich EG. New nomenclature for vulvar disease. Obstet Gynecol. 1976;47:122-124.

Frumkin AP. Reconstruction of male genitalia. Am Rev Soviet Med. 1944;2:14-21.

Fuchs JC, Mitchener JS3rd, Hagen PO. Postoperative changes in autologous vein grafts. Ann Surg. 1978;188:1-15.

Garat JM, Chechile G, Algaba F, et al. Balanitis xerotica obliterans in children. J Urol. 1986;136:436-437.

Gearhart JP, Leonard MP, Burgers JK, Jeffs RD. The Cantwell-Ransley technique for repair of epispadias. J Urol. 1994;15:457-459.

Gearhart JP, Rock JA. Total ablation of the penis after circumcision and electrocautery: a method of management and long-term followup. J Urol. 1989;42:799-801.

Gillies HD, Harrison RH. Congenital absence of the penis. Br J Plast Surg. 1948;1:8-28.

Gil-Vernet S. Diverticulos bulbouretrales y reflujo vesicoureteral. Arch Esp Urol. 1977;30:325.

Goolamali SK, Barnes EW, Irvine WJ, et al. Organ-specific antibodies in patients with lichen sclerosus. Br Med J. 1974;4:78-79.

Greenwell TJ, Venn SN, Mundy AR. Changing practice in anterior urethroplasty. BJU Int. 1999;83:631-635.

Gur U, Jordan GH. Vessel-sparing excision and primary anastomosis (for proximal bulbar urethral strictures). BJU Int. 2008;101(9):1183-1195.

Haertsch PA. The blood supply to the skin of the leg: a post-mortem investigation. Br J Plast Surg. 1981;34:470-477.

Hafez AT, El-Assmy A, Sarhan O, et al. Perineal anastomotic urethroplasty for managing post-traumatic urethral strictures in children: the long-term outcome. BJU Int. 2005;95:403-406.