Chapter 15 Hereditary Fundus Dystrophies

Introduction

Applied anatomy

The hereditary fundus dystrophies are a rare but important group of disorders that primarily involve the outer retina (RPE-photoreceptor complex) and its blood supply (choriocapillaris). It is uncommon for the inner retina or the retinal vasculature to be the primary target. There are two types of photoreceptor cells:

Inheritance

Investigations

Electroretinography

Principles

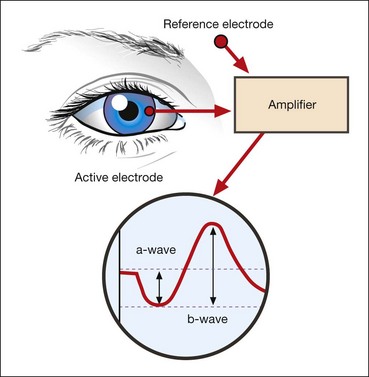

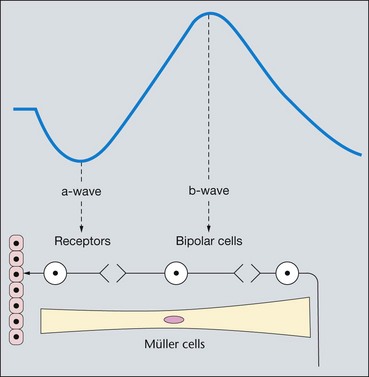

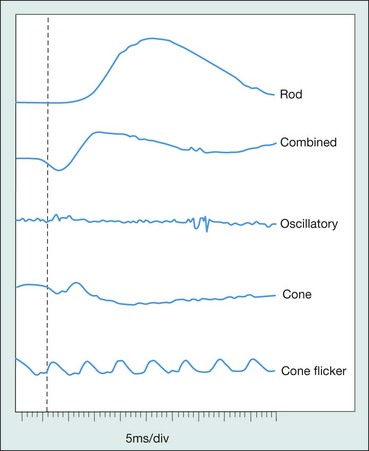

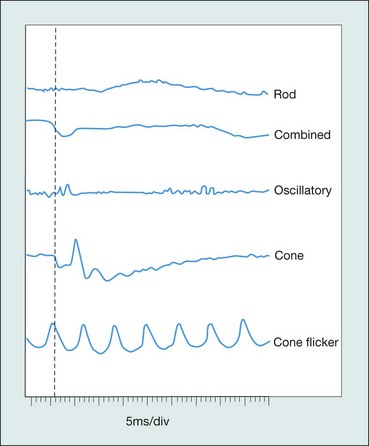

The electroretinogram (ERG) is the record of an action potential produced by the retina when it is stimulated by light of adequate intensity. The recording is made between an active electrode either in contact with the cornea or a skin electrode placed just below the lower eyelid margin, and a reference electrode on the forehead. The potential between the two electrodes is then amplified and displayed (Fig. 15.1). The normal ERG is biphasic (Fig. 15.2).

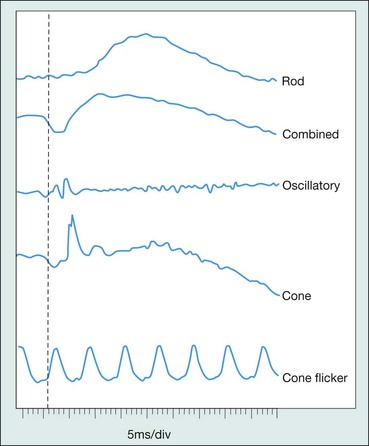

Standard ERG

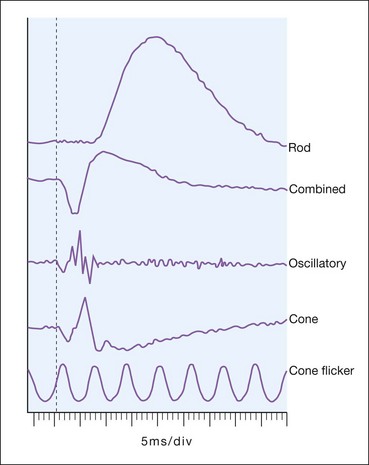

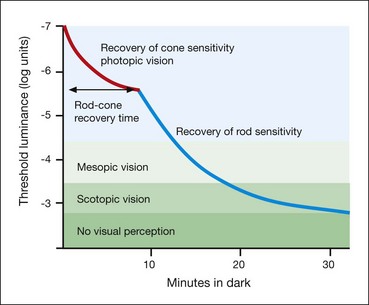

The normal ERG consists of five recordings (Fig. 15.3). The first three are elicited after 30 minutes of dark adaptation (scotopic), and the last two after 10 minutes of adaptation to moderately bright diffuse illumination (photopic). It may be difficult to dark adapt children for 30 minutes and therefore dim light (mesopic) conditions can be utilized to evoke predominantly rod-mediated responses to low intensity white or blue light stimuli.

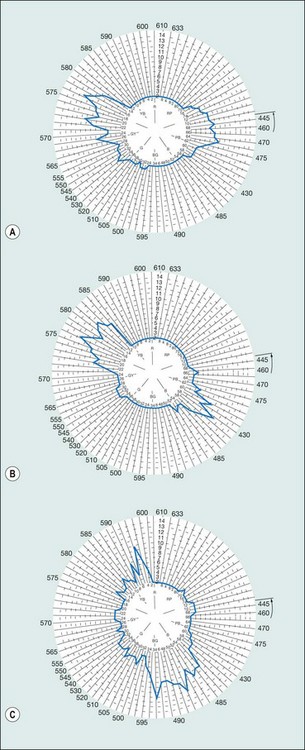

Multifocal ERG

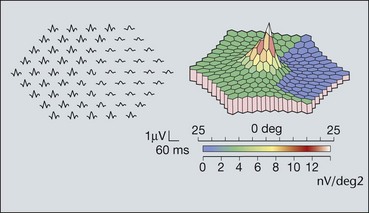

Multifocal ERG is a method of producing topographical maps of retinal function (Fig. 15.4). The stimulus is scaled for variation in photoreceptor density across the retina. At the fovea, where the density of receptors is high, a lesser stimulus is used than in the periphery where receptor density is lower. As with conventional ERG, many types of measurements can be made. Both the amplitude and timing of the troughs and peaks can be measured and reported and the information can be summarized in the form of a three-dimensional plot which resembles the hill of vision. The technique can be used for almost any disorder which affects retinal function.

Electro-oculography

Dark adaptometry

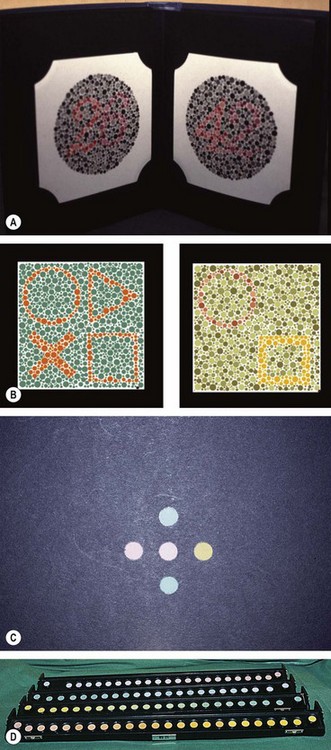

Colour vision tests

Colour vision (CV) testing is sometimes useful in the clinical evaluation of hereditary fundus dystrophies, where dyschromatopsia may be present prior to the development of impairment of visual acuity and visual field loss.

Principles

CV is a function of three populations of retinal cones each with its specific sensitivity; blue (tritan) at 414–424 nm, green (deuteran) 522–539 nm and red (protan) at 549–570 nm.

Colour vision tests

Generalized photoreceptor dystrophies

Typical retinitis pigmentosa

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) defines a clinically and genetically diverse group of diffuse retinal dystrophies initially predominantly affecting the rod photoreceptor cells with subsequent degeneration of cones (rod-cone dystrophy). It is the most commonly encountered hereditary fundus dystrophy with a prevalence of approximately 1 : 5000.

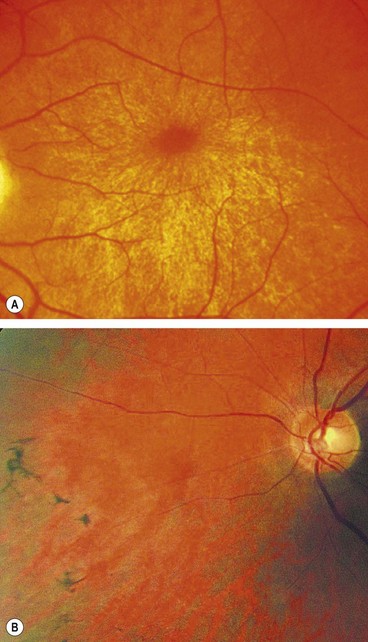

Inheritance

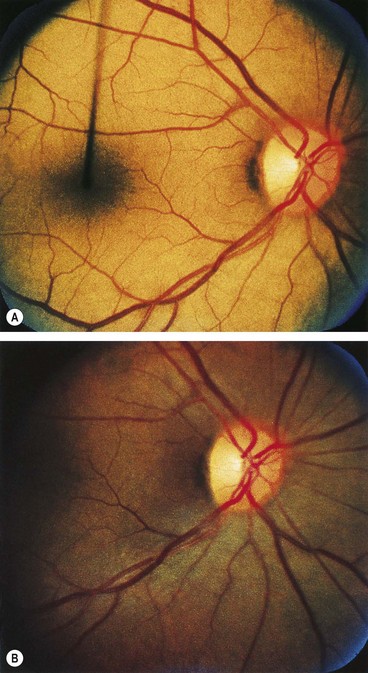

The age of onset, rate of progression, eventual visual loss and associated ocular features are frequently related to the mode of inheritance. RP may occur as an isolated sporadic disorder, or be inherited as AD, AR or XL. Many cases are due to mutation of the rhodopsin gene. XL is the least common but most severe form and may result in complete blindness by the third or fourth decades. Female carriers may have normal fundi or show a golden-metallic (’tapetal’) reflex at the macula (Fig. 15.9A) and/or small peripheral patches of bone-spicule pigmentation (Fig. 15.9B). RP, often atypical, may also be associated with systemic disorders which are usually AR (see below).

Diagnosis

The diagnostic criteria for RP comprise bilateral involvement, with loss of peripheral and night vision. The classical triad of RP is: (a) arteriolar attenuation, (b) retinal bone-spicule pigmentation and (c) waxy disc pallor.

Ocular associations

Regular follow-up of patients with RP is essential to detect other vision-threatening complications, some of which may be amenable to treatment.

Atypical retinitis pigmentosa

Atypical RP describes conditions that are closely related to typical RP or represent incomplete forms of the disease.

Important systemic associations

Bassen–Kornzweig syndrome (abetalipoproteinaemia)

Refsum disease

Kearns–Sayre syndrome

Kearns–Sayre syndrome is characterized by chronic progressive external ophthalmoplegia (Fig. 15.14C) associated with other systemic problems, which are described in Chapter 19. The fundus usually has a ‘salt and pepper’ appearance most striking at the macula; less frequently findings are typical RP or choroidal atrophy similar to choroideremia.

Bardet–Biedl syndrome

Usher syndrome

Usher syndrome is a distressing condition which accounts for about 5% of all cases of profound deafness in children, and is responsible for about half of all cases of combined deafness and blindness. There are three major types in which sensorineural deafness is associated with typical RP with or without vestibular dysfunction.

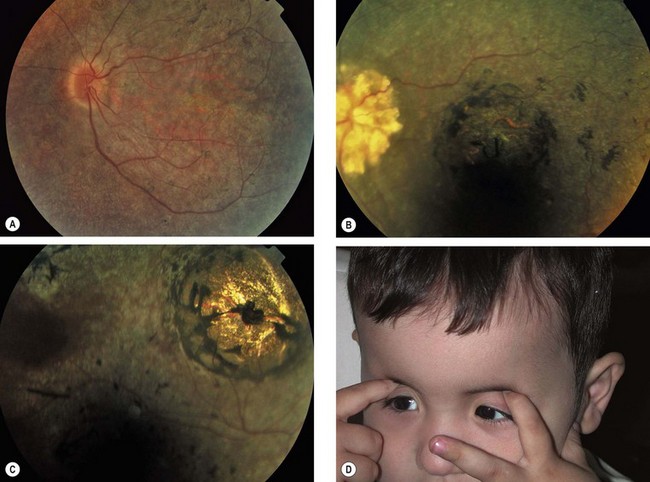

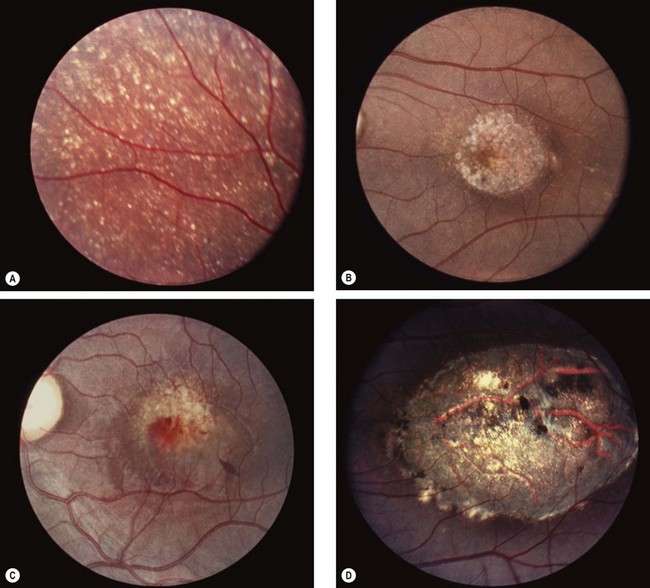

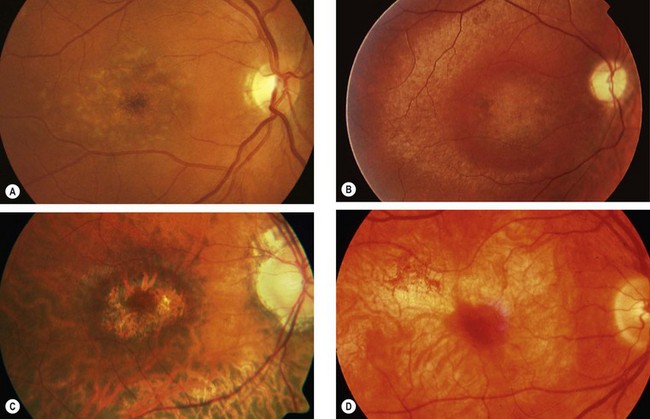

Progressive cone dystrophy

Progressive cone dystrophy predominantly affects the cone system. In some cases there is no evidence of rod dysfunction whilst in others rod dysfunction subsequently develops but cone deficiency still predominates (cone-rod dystrophy).

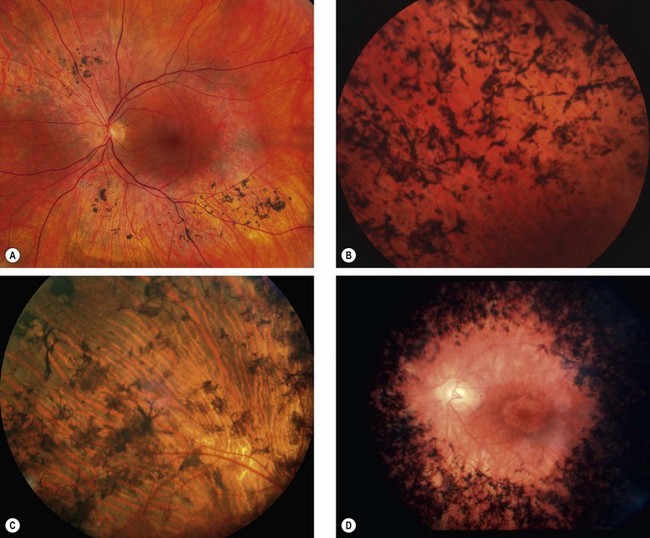

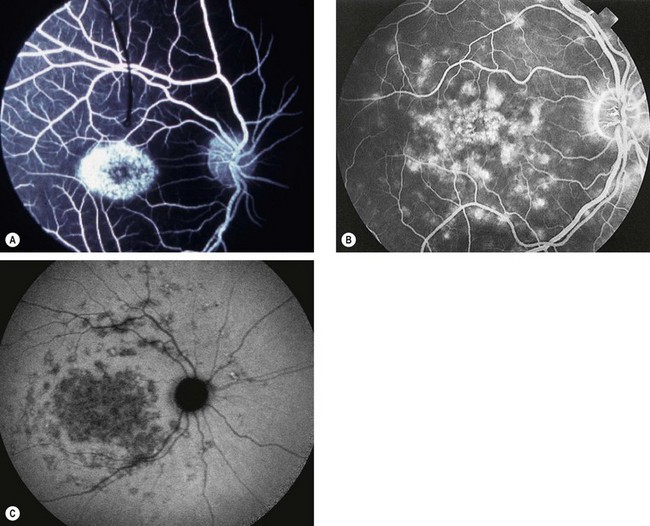

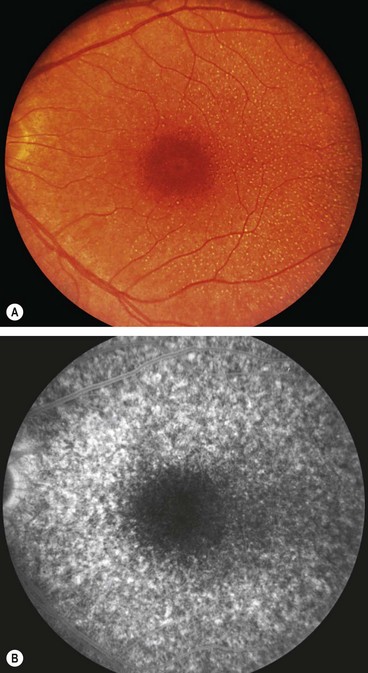

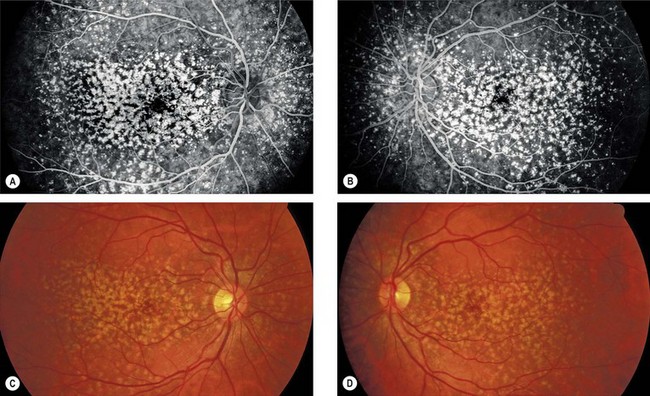

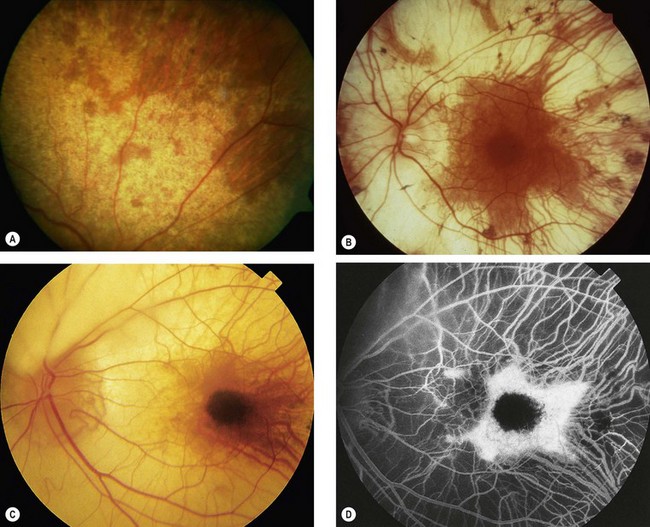

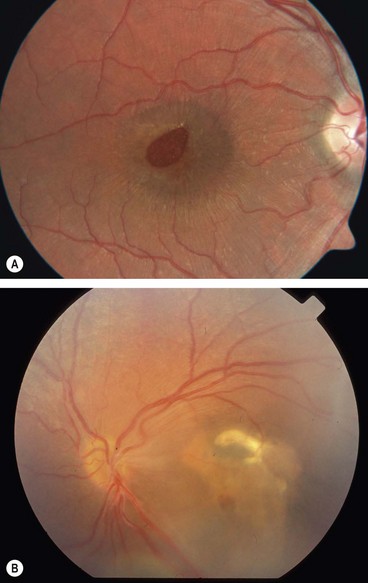

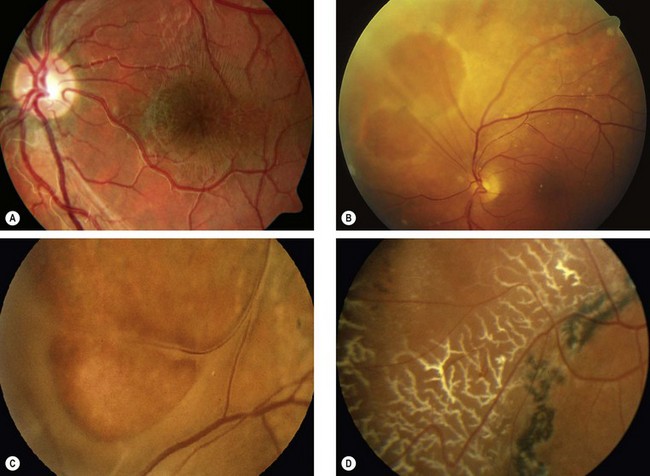

Fig. 15.15 Progressive cone dystrophy. (A) Early pigment mottling; (B) Golden sheen in XL disease; (C) ‘bull’s eye’ maculopathy; (D) geographic atrophy

(Courtesy of Moorfields Eye Hospital – fig. A)

Table 15.1 Other causes of bull’s eye macula

Leber congenital amaurosis

Leber congenital amaurosis is a severe rod-cone dystrophy that is the commonest genetic cause of visual impairment in infants and children. It carries a very poor prognosis.

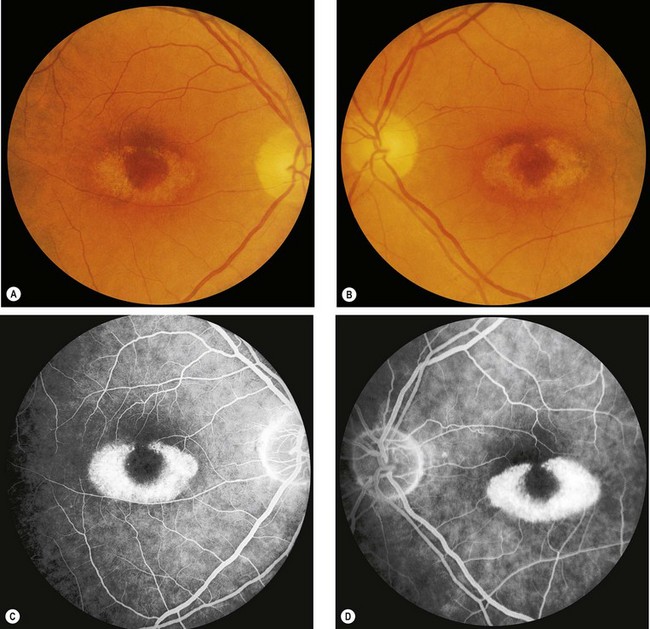

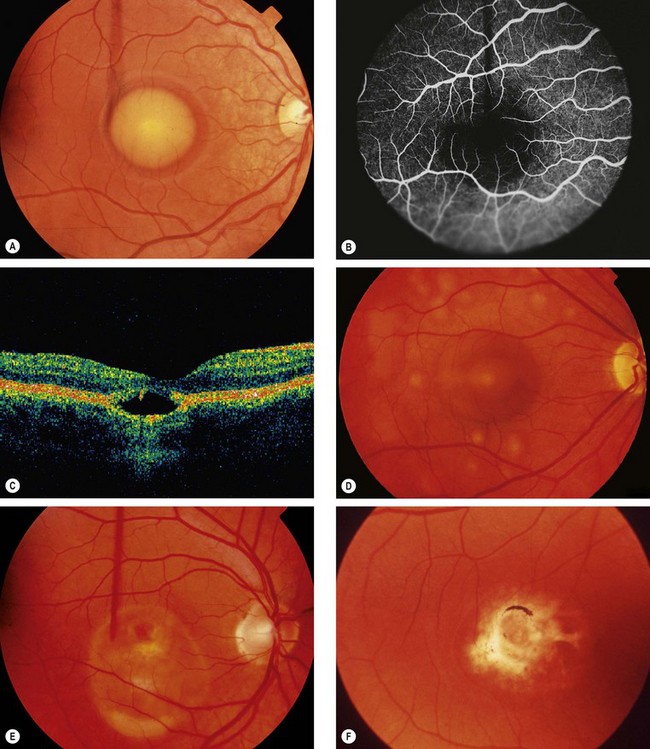

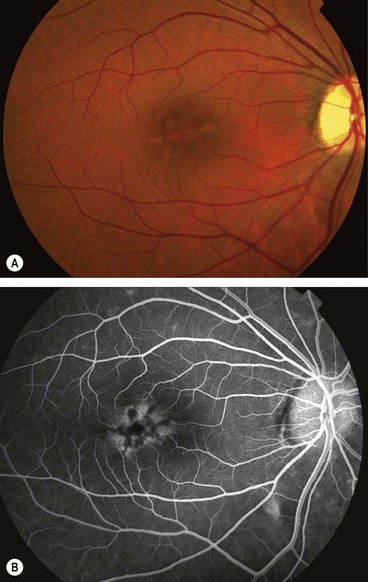

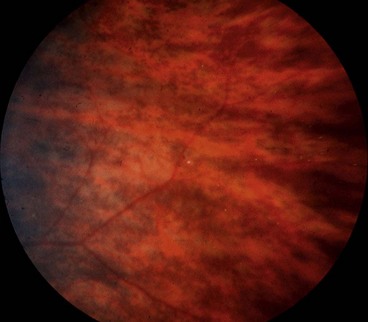

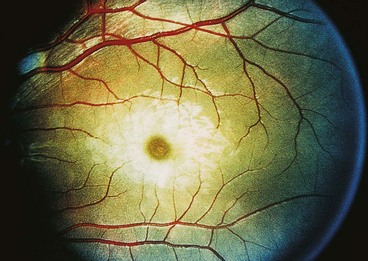

Stargardt disease and fundus flavimaculatus

Stargardt disease (juvenile macular dystrophy) and fundus flavimaculatus (FFM) are regarded as variants of the same disease despite presenting at different times and carrying different prognoses. The condition is characterized by diffuse accumulation of lipofuscin within the RPE that results in vermilion fundus and a ‘dark choroid’ seen on FA (see below).

Bietti corneoretinal crystalline dystrophy

Bietti dystrophy is characterized by deposition of crystals in the retina and the superficial peripheral cornea. It is much more common in East Asians, particularly Chinese, than other ethnicities.

Alport syndrome

Familial benign fleck retina

Familial benign fleck retina is a very rare disorder which is asymptomatic and therefore usually discovered by chance.

Pigmented paravenous chorioretinal atrophy

Paravenous chorioretinal atrophy is an innocuous and asymptomatic condition that is usually non-progressive. The fundus changes are bilaterally symmetric.

Congenital stationary night blindness

Congenital stationary night blindness (CSNB) refers to a group of disorders characterized by infantile onset nyctalopia and non-progressive retinal dysfunction. The fundus appearance may be normal or abnormal.

With normal fundus

CSNB with a normal fundus appearance is sometimes classified into type 1 (complete) and type 2 (incomplete) forms. The former is characterized by complete absence of rod pathway function and essentially normal cone function clinically and on ERG, the latter has impairment with both rod and cone function. Mutations in numerous genes have been identified as causing the CSNB phenotype, with XL, AD and AR inheritance patterns.

With abnormal fundus

Macular dystrophies

Juvenile Best macular dystrophy

Best (vitelliform) macular dystrophy is the second most common macular dystrophy.

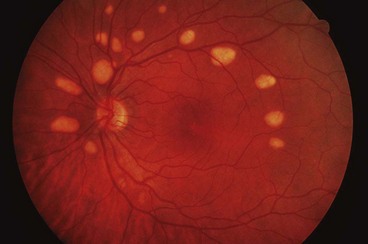

Multifocal vitelliform lesions without Best disease

Occasionally multifocal vitelliform lesions (Fig. 15.28), identical to those in Best disease, may become manifest in adult life and give rise to diagnostic problems. However, in these patients the EOG is normal and the family history is negative. Occasionally Best dystrophy may present with multifocal lesions.

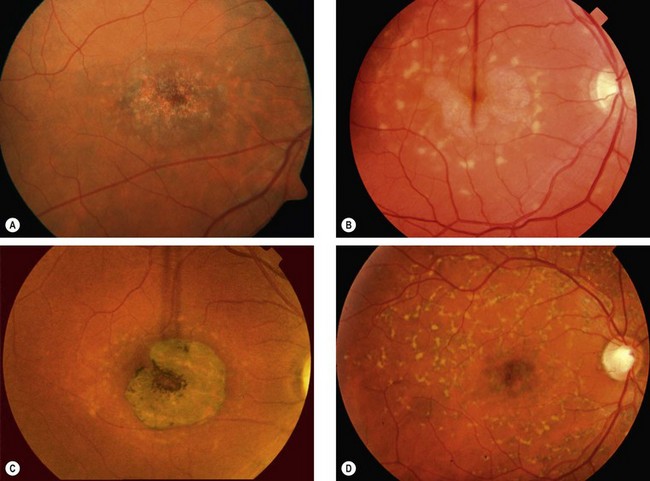

Pattern dystrophy

Pattern dystrophy is a generic term that encompasses several retinal dystrophies exhibiting yellow, orange or grey deposits at the macula that have a variety of morphologies. The lesions are associated with the accumulation of lipofuscin at the level of the RPE. Pattern dystrophy is usually present in isolation but has also been described in patients with myotonic dystrophy, Kjellin syndrome (spastic paraplegia and dementia) and pseudoxanthoma elasticum. The main phenotypes having the following common characteristics are discussed below: (a) AD inheritance, (b) variable expressivity, (c) bilateral symmetrical involvement, (d) relatively benign course and (e) normal ERG but occasionally abnormal EOG.

Adult-onset macular vitelliform dystrophy

In contrast to juvenile Best disease, the foveal lesions are smaller, present later and do not demonstrate similar evolutionary changes.

Butterfly-shaped macular dystrophy

Multifocal pattern dystrophy simulating fundus flavimaculatus

North Carolina macular dystrophy

North Carolina macular dystrophy is a very rare non-progressive condition. It was first described in families living in the mountains of North Carolina and subsequently in many unrelated families in other parts of the world.

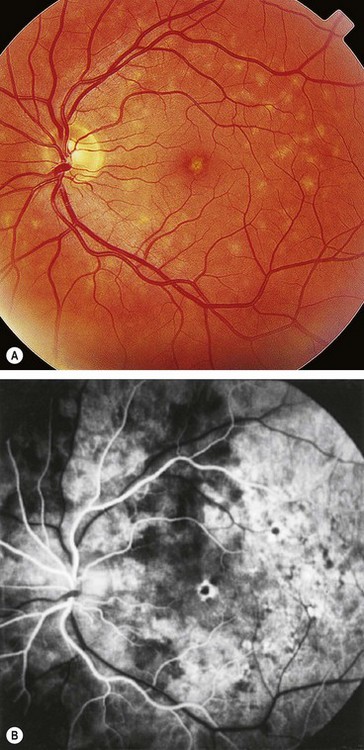

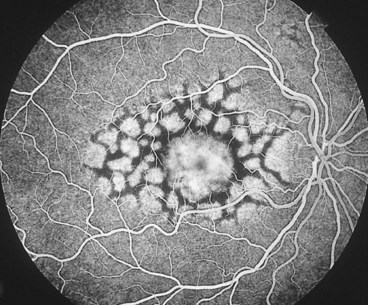

Familial dominant drusen

Familial drusen (Doyne honeycomb choroiditis, malattia leventinese) is thought to represent an early-onset variant of age-related macular degeneration.

Sorsby pseudoinflammatory dystrophy

Sorsby pseudoinflammatory macular dystrophy, also referred to as hereditary haemorrhagic macular dystrophy, is a very rare condition that results in bilateral visual loss in the 5th decade of life.

Central areolar choroidal dystrophy

Sjögren–Larsson syndrome

Sjögren–Larsson syndrome is a neurocutaneous disorder characterized by congenital ichthyosis, spasticity, convulsions and mental handicap with reduced life expectancy. The basic metabolic defect is deficient activity of fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase.

Generalized choroidal dystrophies

Choroideremia

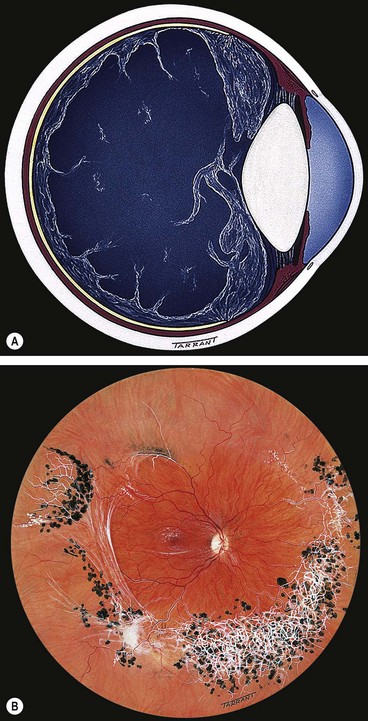

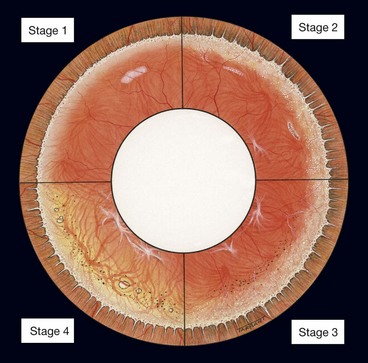

Choroideremia is a progressive, diffuse degeneration of the choroid, RPE and retinal photoreceptors.

Gyrate atrophy

Gyrate atrophy is a metabolic disorder caused by a mutation of the gene encoding the main ornithine degradation enzyme, ornithine aminotransferase. Deficiency of the enzyme leads to elevated ornithine levels in the plasma, urine, CSF and aqueous humour.

Generalized choroidal dystrophy

Progressive bifocal chorioretinal atrophy

Vitreoretinal dystrophies

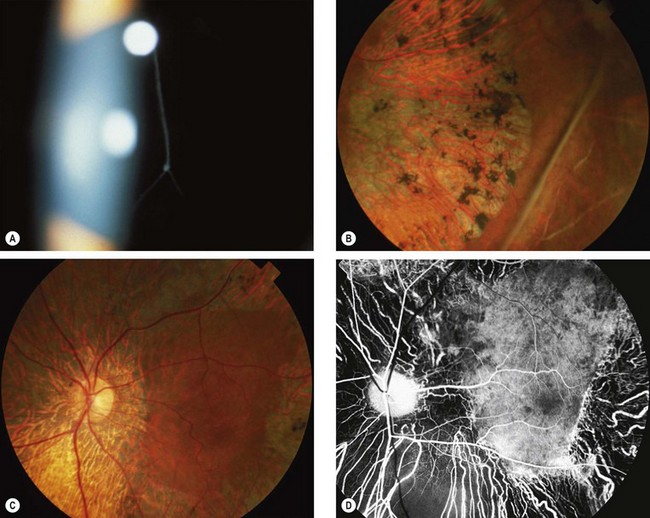

Juvenile X-linked retinoschisis

Pathogenesis

Juvenile retinoschisis is characterized by bilateral maculopathy, with associated peripheral retinoschisis in 50% of patients. The basic defect is in the Müller cells, causing splitting of the retinal nerve fibre layer from the rest of the sensory retina. This differs from acquired (senile) retinoschisis in which splitting occurs at the outer plexiform layer.

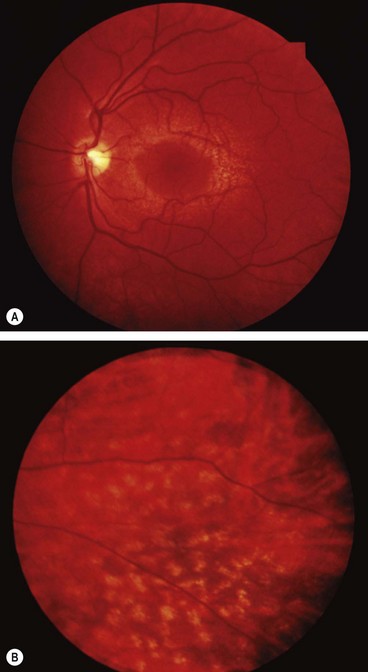

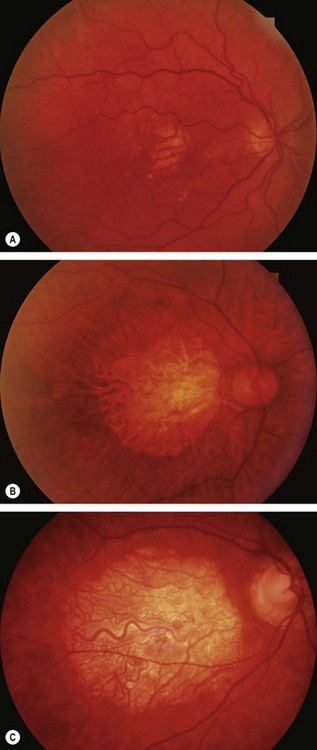

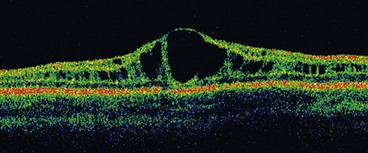

Diagnosis

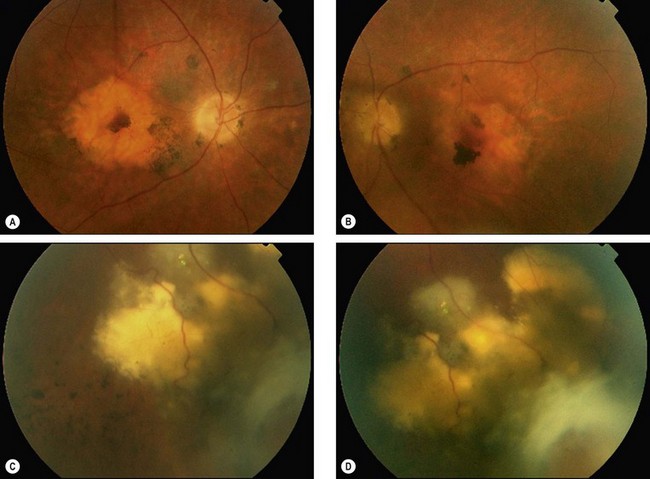

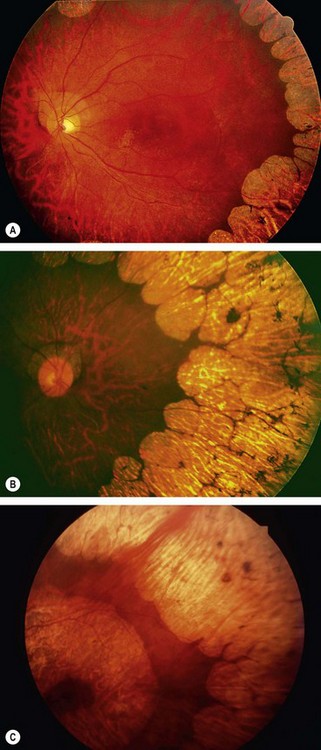

Fig. 15.44 Juvenile retinoschisis. (A) ‘Bicycle wheel’-like maculopathy; (B) inner leaf defect; (C) ‘vitreous veils’; (D) peripheral dendritic lesions

(Courtesy of K Slowinski – fig. A; C Barry – figs B and C; Moorfields Eye Hospital – fig. D)

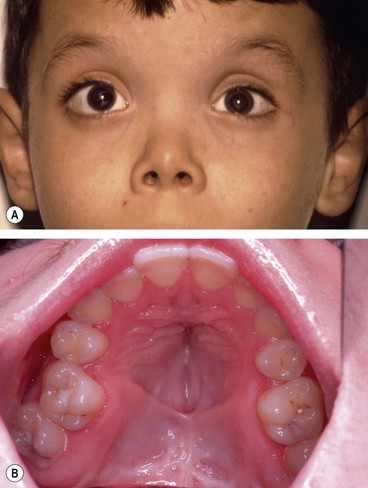

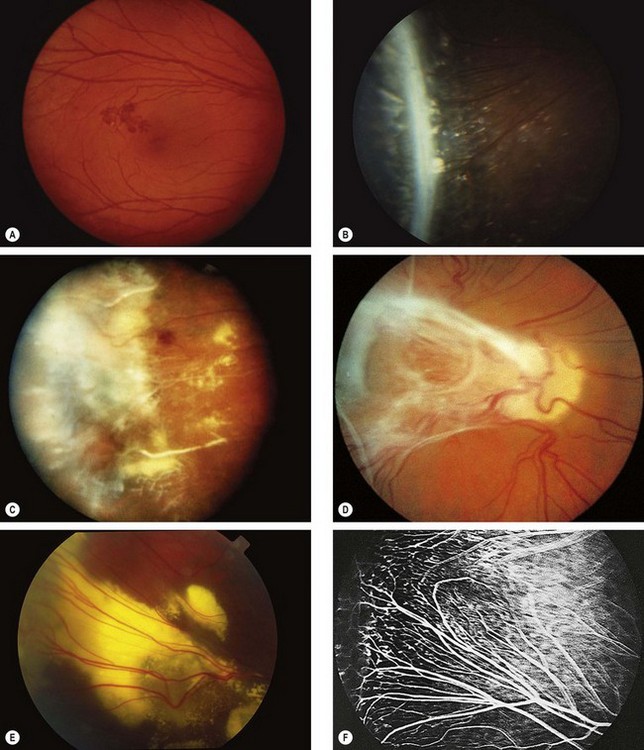

Stickler syndrome

Stickler syndrome (hereditary arthro-ophthalmopathy) is a disorder of collagen connective tissue. Inheritance is AD with complete penetrance but variable expressivity. Stickler syndrome is the commonest inherited cause of retinal detachment in children.

Classification

Systemic features

Ocular features

Wagner syndrome

Wagner syndrome (erosive vitreoretinopathy) shows similar vitreous changes to Stickler syndrome but is not associated with systemic abnormalities.

Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy

Familial exudative vitreoretinopathy (Criswick–Schepens syndrome) is a slowly-progressive condition characterized by failure of vascularization of the temporal retinal periphery, similar to that seen in retinopathy of prematurity, but not associated with low birth weight and prematurity.

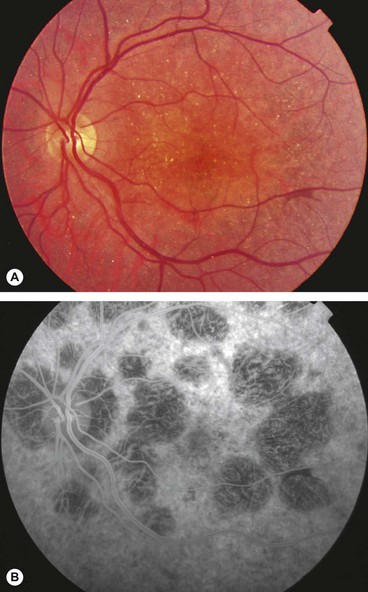

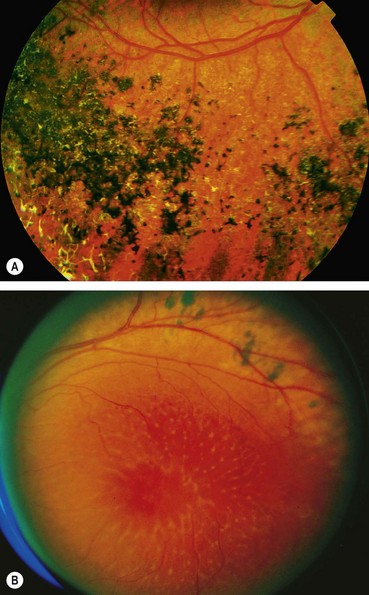

Enhanced S-cone syndrome and Goldmann–Favre syndrome

There appears to be an overlap between these two conditions, and it is believed that the latter may represent a more severe variant of the former.

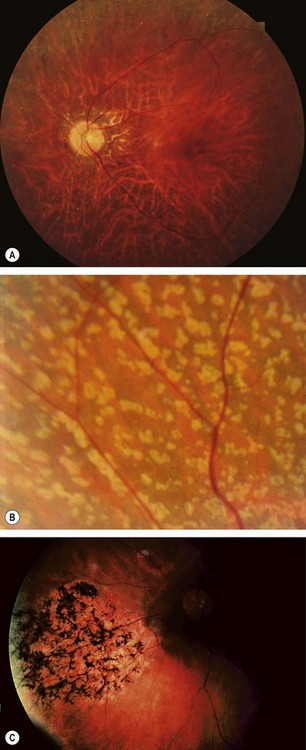

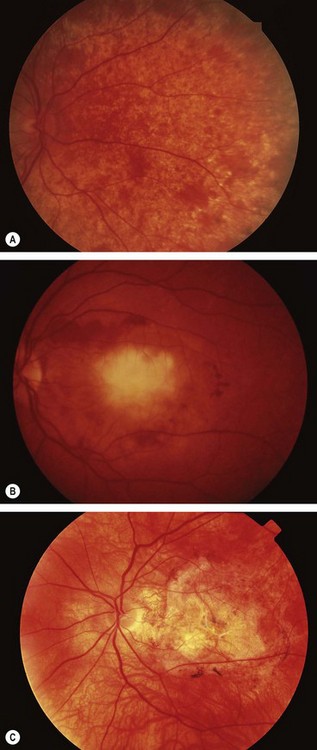

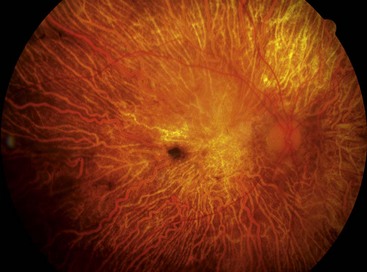

Fig. 15.52 Enhanced S-cone and Goldmann–Favre syndrome. (A) Severe pigment clumping; (B) macular schisis and pigmentary changes along the arcade

(Courtesy of D Taylor and CS Hoyt, from Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, Elsevier Saunders 2005 – fig. A; J Donald M Gass, from Stereoscopic Atlas of Macular Diseases, Mosby 1997 – fig. B)

Snowflake vitreoretinal degeneration

Dominant neovascular inflammatory vitreoretinopathy

Dominant vitreoretinochoroidopathy

Albinism

Introduction

Albinism is a genetically determined, heterogeneous group of disorders of melanin synthesis in which either the eyes alone (ocular albinism) or the eyes, skin and hair (oculocutaneous albinism) may be affected. The latter may be either tyrosinase-positive or tyrosinase-negative. The different mutations are thought to act through a common pathway involving reduced melanin synthesis in the eye during development. Tyrosinase activity is assessed by using the hair bulb incubation test, which is reliable only after 5 years of age. Patients with albinism have an increased risk of cutaneous basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma that usually occurs before the fourth decade.

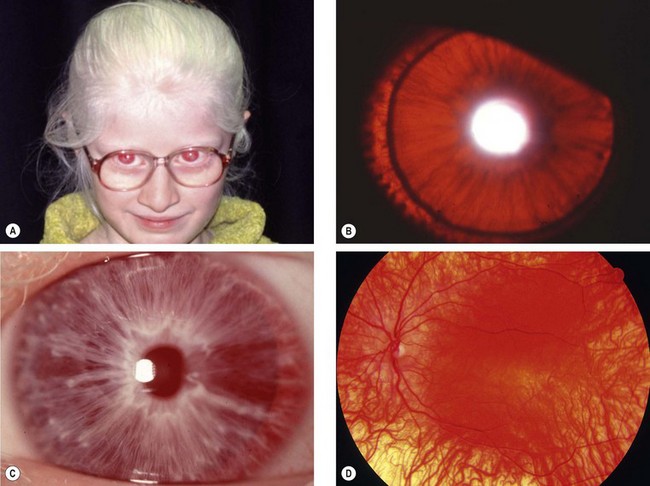

Tyrosinase-negative oculocutaneous albinism

Tyrosinase-negative (complete) albinos are incapable of synthesizing melanin and have white hair and very pale skin (Fig. 15.54A) throughout life with lack of melanin pigment in all ocular structures.

Tyrosinase-positive oculocutaneous albinism

Tyrosinase-positive (incomplete) albinos synthesize variable amounts of melanin. The hair may be white, yellow or red and darkens with age. Skin colour is very pale at birth but usually darkens by 2 years of age (Fig. 15.55A).

Fig. 15.55 Tyrosinase-positive oculocutaneous albinism. (A) Fair hair and normal skin colour; (B) mild fundus hypopigmentation

(Courtesy of B Majol – fig. A)

Associated systemic syndromes

Ocular albinism

Involvement is predominantly ocular with normal skin and hair although occasionally hypopigmented skin macules may be seen.

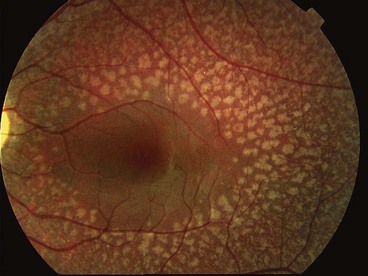

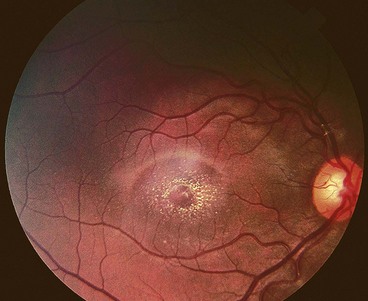

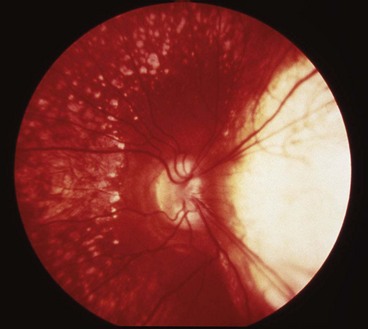

Cherry-red spot at macula

Pathogenesis

A cherry-red spot at the macula (Fig. 15.58) is a clinical sign seen in the context of thickening and loss of transparency of the retina at the posterior pole. The fovea, being the thinnest part of the retina and devoid of ganglion cells, retains relative transparency, allowing persistent transmission of the underlying highly vascular choroidal hue. This striking lesion occurs in the sphingolipidoses, which comprise a group of rare inherited metabolic diseases characterized by the progressive intracellular accretion of excessive quantities of certain glycolipids and phospholipids in various tissues of the body, including the retina. The lipids accumulate in the ganglion cell layer of the retina, giving the retina a white appearance. As ganglion cells are absent at the foveola, this area retains relative transparency and contrasts with the surrounding opaque retina. With the passage of time the ganglion cells die and the spot becomes less evident. The late stage of the disease is characterized by degeneration of the retinal nerve fibre layer and consecutive optic atrophy. The following diseases are associated with a cherry-red spot.

GM1 gangliosidosis (generalized)

Mucolipidosis type I (sialidosis)

GM2 gangliosidosis

Niemann–Pick disease

There are three main types of Niemann disease (A–C) but only the first two are associated with a cherry-red spot. The main ocular features of type C (chronic neuropathic) are gaze palsy and abnormal eye movements.