CHAPTER 19 Pathology and Management of Periodontal Problems in Patients with HIV Infection

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is characterized by profound impairment of the immune system. The condition was first reported in 1981, and a viral pathogen, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), was identified in 1984.179 The condition was originally believed to be restricted to male homosexuals. Subsequently, it was also identified in male and female heterosexuals and bisexuals who participated in unprotected sexual activities or abused injected drugs.153 Currently, sexual activity and drug abuse remain the primary means of transmission.

HIV has a strong affinity for cells of the immune system, most specifically those that carry the CD4 cell surface receptor molecule. Thus helper T lymphocytes (T4 cells) are most profoundly affected, but monocytes, macrophages, Langerhans cells, and some neuronal and glial brain cells may also be involved.102 Viral replication occurs continuously in the lymphoreticular tissues of lymph nodes, spleen, gut-associated lymphoid cells, and macrophages.231,232

In recent years, combined therapeutic regimens consisting of antiretroviral agents and protease-inhibiting drugs have resulted in marked improvement in the health status of HIV-infected individuals and occasionally a reduction in viral plasma bioloads below detectable levels (<50 copies per milliliter), although the infection may still be transmissible.64,91,96,237 Current evidence indicates that the virus is never completely eradicated; rather, it is sequestered at low levels in resting CD4 cells even in individuals with no detectable plasma viral ribonucleic acid (RNA).40,63 These findings suggest that effective combination drug therapy may be necessary for the lifetime of infected individuals. Long-term control of the infection may be difficult because the antiviral agents currently used have many adverse side effects and readily develop drug-resistant variant strains.231

Pathogenesis

In untreated or inadequately treated HIV infection, the overall effect is gradual impairment of the immune system by interference with T4 (CD4) lymphocytes and other immune cell functions.232 Recent evidence indicates that innate immune response may play a role in controlling HIV replication. A genetic variation associated with the expression of CCR5 and its ligand has been found to decrease susceptibility to HIV infection, as well as delay clinical progression independent of their effects on viral replication. This may serve to partially explain the lack of progression of HIV infection in some individuals.102

B lymphocytes are not infected, but the altered function of infected T4 lymphocytes secondarily results in B-cell dysregulation and altered neutrophil function.120 This may place the HIV-positive individual at increased risk for malignancy and disseminated infections with microorganisms such as viruses, mycobacterioses, and mycoses.90,164,171 HIV-positive individuals are also at increased risk for adverse drug reactions because of altered antigenic regulation.

Epithelial cells of the mucosa may become infected and may allow access of the virus into the bloodstream. Most evidence, however, indicates that oral transmucosal viral transmission occurs after mild or severe traumatic injury or punctures of the mucous membranes. This allows for infection of circulating host defense cells such as lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells.36,202

HIV has been detected in most body fluids, although it is found in high quantities only in blood, semen, and cerebrospinal fluid. Transmission occurs almost exclusively by sexual contact, illicit use of injection drugs, or exposure to blood or blood products. Transmission after human bites has been reported, although the risk is extremely low.168,226

The high-risk population includes homosexual and bisexual men; users of illegal injection drugs; persons with hemophilia or other coagulation disorders; recipients of blood transfusions before April 1985; infants of HIV-infected mothers (in whom transmission occurs by fetal transmission, at delivery, or by breastfeeding); promiscuous heterosexuals; and individuals who engage in unprotected sex with HIV-positive cohorts.95 Heterosexual transmission is a common cause of AIDS in the world population and is increasing significantly in the United States.34,159 Transmission is more likely to occur through contact with HIV-infected individuals with a high plasma bioload of the virus.159,181 HIV transmission has also been reported to occur through organ transplantation and artificial insemination.39

Some short-term studies have suggested that HIV positive individuals successfully treated with anti-retroviral therapy (no detectable viral load) cease to be infectious to others.28,169 However, Wilson et al233 have developed a mathematical model that indicates that the potential of HIV transmission to an uninfected individual by a heterosexual partner with an undetectable viral load is low but not without risk. This risk appears to increase with more frequent exposures and the presence of other sexually transmitted diseases. Incomplete adherence to antiretroviral therapy could further increase the risk of transmission. Unprotected sex in this scenario creates a four times greater risk of HIV transmission than condom use.

The concept of serosorting has been advocated with increasing frequency in an effort to allow unprotected sex in male homosexuals who are both HIV-positive or both HIV-negative. This is the practice of preferentially having sex only with partners of concordant HIV status while selectively using condoms with HIV-discordant partners. There does appear to be some reduction in risk to others by HIV-positive individuals who only have sex with other seropositive individuals. However, the degree of risk for other sexually transmitted diseases remains high. Among HIV-negative individuals, serosorting presents an increased risk of HIV transmission because some HIV-infected individuals are not aware of their disease status or do not reveal their status. Consequently, the consistent use of condoms is strongly recommended for both concordant and discordant sexual activity.78

Epidemiology and Demographics

As of the end of 2007, 1,051,875 AIDS cases were estimated to have occurred in the United States, and more than 500,000 deaths have been attributed to the syndrome.31 Worldwide estimates indicate that as of 2007, 33 million to 50 million individuals are currently living with HIV (HIV-1, HIV-2). In 2007 there were 2.7 million new HIV infections and 2 million HIV-related deaths worldwide, mostly in underdeveloped countries.219 Sub-Saharan Africa continues to be the global epicenter of the AIDS pandemic and by 2005 between 2.4 million and 3.3 million individuals were estimated to have lost their lives worldwide as the result of HIV.95 The increase in numbers of patients living with AIDS in the United States and other developed countries has resulted in part from prolonged survival, since the advent of multidrug highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART).20,64,160,222 Thus AIDS represents the most serious medical crisis in world history.219

AIDS affects individuals of all ages, but more than 98% of cases occur among adults and adolescents over age 12. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates indicate that in 2006 the majority of newly infected adult victims in the United States were men, 53% of whom were homosexuals or bisexuals. An additional 4% of this group also used illicit injection drugs. Transmission through injection drug use alone infected 12%, while 31% of all patients with AIDS in the United States contracted the infection through heterosexual contact, usually with a high risk individual.31,34 More than 19% of AIDS victims are women, the majority of whom are those who have sex with intravenous drug users or bisexual men.35 Other women with AIDS were born in countries such as Haiti or one of several high-incidence African nations in which heterosexual contact is the major mode of transmission. Only one individual contracted AIDS from blood products or blood transfusions in the United States in 2007 because of stringent blood bank controls. This mode of transmission continues to be a threat, however, in undeveloped countries. A disproportionately high number of black and Hispanic male homosexuals, male and female heterosexuals, and children of affected women have HIV infection. The major risk factor for this disparity appears to be a more frequent history of use of injection drugs and needle sharing and unprotected sexual activity in these groups.31,34,127 It is of interest to note that mother-to-child transmission of HIV in the United States has progressively decreased since its peak in 1992 because of the use of antiretroviral therapy.215

Transmission from health care workers to patients has been documented on three occasions, with one dentist infecting six patients either accidentally or deliberately.119,133 Conversely, seroconversion has been documented in 103 health care workers after occupational injury, usually related to management of patients with high plasma viral loads. The majority of these incidents involved nurses, and no documented seroconversion has been reported among dental health care workers.104,133,236

Classification and Staging

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the CDC each have published guidelines regarding the definition of HIV infection and HIV-disease staging. In both sets of guidelines, HIV infection is confirmed, if possible, based on laboratory criteria. However, in many parts of the world, laboratory testing is not available. Consequently, in the WHO concept, clinical findings may be used to establish the diagnosis and determine eligibility for antiretroviral therapy.

WHO staging is primarily based on clinical appearance of the disease and includes the following:

AIDS may be present in either clinical stage 3 or stage 4 disease. A CD4 count of less than 350 per mm3 is considered diagnostic for AIDS in adults and children 5 years of age or older; advanced HIV infection in infants is based on CD4+ cells <30%, if younger than 12 months; CD4+ cells <25% among those ages 12 to 35 months; and CD4+cells <20% among those ages 36 to 59 months. (These are WHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunologic classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children.1,32)

In 1982 the CDC developed a surveillance case definition for AIDS based on the presence of opportunistic illnesses or malignancies secondary to defective cell-mediated immunity in HIV-positive individuals.32,33 The 1993 revision added invasive cervical cancer in women, bacillary tuberculosis, and recurrent pneumonia to the AIDS designation. Currently, any of 25 specific clinical conditions found in HIV-positive individuals can establish the diagnosis of AIDS (Box 19-1).The most significant change in the most recent CDC case definition was the inclusion of severe immunodeficiency (CD4+ T lymphocyte count <200/mm3 or CD+T lymphocyte percentage <14% of total lymphocytes) as definitive for AIDS. This change was based on recognition that severe immunodeficiency results in increased risk for opportunistic, life-threatening conditions. Many HIV-positive individuals have been designated as patients with AIDS solely because of low CD4 cell count or percentage, even in the absence of life-threatening conditions. More recently, HIV plasma bioload has been identified as a significant factor related to the transmissibility and severity of the disease.

BOX 19-1 From Centers for Disease Control: MMWR 41:RR-17, 1993.

CDC AIDS Surveillance Case Definition Conditions

The number of individuals living with AIDS in the United States has greatly increased in recent years because of the development of HAART, which combines various types of antiretroviral drugs, protease inhibitors, and fusion inhibitors.93,108 Infected individuals treated with HAART may experience a marked rise in CD4 cell levels and a decreased plasma viral load. CD4 counts may reach normal levels, and viral bioload may decrease to a point below the level of detection.17,163 Despite this improvement, these individuals are still considered to have AIDS because the virus is apparently sequestered somewhere in the body. The patient remains potentially infectious to others, and viral activity may resume if medications are discontinued or if the virus becomes drug resistant.* A few weeks to a few months after initial exposure, some HIV-infected individuals may experience acute symptoms, such as sudden onset of an acute mononucleosis-like illness characterized by malaise, fatigue, fever, myalgia, erythematous cutaneous eruption, oral candidiasis, oral ulcerations, and thrombocytopenia.66,132,221 This acute phase may last for up to 2 weeks, with seroconversion occurring 3 to 8 weeks later.222 However, antigenic viremia may sometimes be present for an extended time before seroconversion occurs.103,118 Some individuals experience asymptomatic HIV infection, whereas others may become asymptomatic after the initial acute infection. In either case, infected individuals eventually become seropositive for HIV antibody, but the mean time from infection until development of AIDS is now estimated to be up to 15 years or more.103,118

CDC Surveillance Case Classification

AIDS patients have been grouped as follows, according to the CDC Surveillance Case Classification (1993)32:

The CDC staging categories reflect progressive immunologic dysfunction, but patients do not necessarily progress serially through the three stages, and the predictive value of these categories is not known. However, because HAART drugs may cause severe adverse side effects, many AIDS treatment centers continue to follow these guidelines in determining when to initiate or discontinue multidrug therapy.13,24,27,94

Antiretroviral Therapy

To date, 32 drugs or drug combinations of 6 separate classes have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of HIV/AIDS infection (Box 19-2). The goals of therapy are to reduce morbidity and mortality and improve and prolong life. To achieve this, it is necessary to suppress plasma viremia and improve or preserve immunologic function. However, total eradication of HIV does not appear to be currently possible because reservoirs of latently infected CD4 cells are established early in the infection and persist even with treatment.151 Anatomic reservoirs of infection have been located in the gastrointestinal and reproductive tracts and in breast, lung, and brain tissue, and recently, the oral cavity has been proposed as an anatomic reservoir because a small percentage of HIV-infected individuals were found to be salivary hyperexcretors of HIV.202

BOX 19-2 From FDA http://www.fda.gov.

Antiretroviral Drugs Approved for Use by the Food and Drug Administration

Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) were the first class of antiretrovirals developed. They act by competing for incorporation into the proviral chain, eliminating chain elongation. They are effective against both HIV-1 and HIV-2. NRTIs are the principal drugs in use today in drug combinations.

Nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI) bind to the active site in the developing HIV-1 viral chain and arrest its development. These drugs are quite effective but rapidly develop resistance by a single step-mutation.

Protease inhibitors are active against both HIV-1 and HIV-2. They bind to the HIV protease enzyme and result in formation of noninfectious HIV virions. Fusion inhibitors bind to the gp41 glycoprotein membrane on HIV and prevent virus fusion into susceptible CD4 cells. The drugs are administered by subcutaneous injection.66,218

Drugs in each category potentially have adverse effects. NRTI drugs may induce a nonspecific gastrointestinal syndrome that begins with nausea and vomiting and abdominal pain but may rapidly progress to hepatic or respiratory failure and pancreatitis. Other NRTIs may induce bone marrow suppression, peripheral neuropathy, pancreatitis, hepatotoxicity, and visceral adiposity (lipodystrophy).

NNRTIs are potent but may lead to rapid development of resistance and cross-resistance to all drugs in the category. The NNRTIs have the potential for adverse interactions with other HIV drugs, especially protease inhibitors, and adverse drug interactions are common with all drugs that are metabolized by the hepatic p450 system, principally the CYP3A4 enzyme. Stevens-Johnson syndrome may develop, and hepatic and central nervous system manifestations are common.

Protease inhibitors (PIs) are potent antiretrovirals that also are metabolized by the CYP3A4 isoenzyme of the hepatic p450 system, which means that adverse drug interactions are common to other antiretroviral agents and non-HIV agents. Gastrointestinal intolerance, hyperlipidemia, insulin resistance, and lipodystrophy are common.

The only fusion inhibitor currently approved is Enfuvirtide. Since it is administered subcutaneously, injection site reactions are common. Enfuvirtide is rarely used alone in management of HIV infection.232

Combined antiretroviral drug therapy has been extremely successful in changing HIV infection from a rapidly progressive fatal disease to a chronic condition that often can be managed successfully and improve survival rates to nearly normal while suppressing or eliminating susceptibility to some opportunistic diseases and disorders.

Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy

In HAART therapy, combinations of three or more antiretroviral drugs are administered simultaneously for long periods of time in an effort to block HIV-replication and plasma viral load and restore immune function while minimizing antiretroviral drug resistance and adverse drug effects. The goal is improvement in quality of life and reduction in HIV-related morbidity and mortality. Three commonly used combinations are one NNRTI plus two NRTI; one or two PIs plus two NRTIs; or three NRTIs. One NRTI three drug combination is available in a single tablet but this antiretroviral therapy does not necessarily qualify as HAART.65

Considerable controversy has existed for several years in deciding the best time to initiate HAART. Some authorities felt that the drugs should not be administered until significant immune suppression occurred. It was believed that this approach would minimize the side effects and the risk of developing drug resistance. Others advocated initiation of therapy as soon as the diagnosis was established. More recently, evidence has indicated that early treatment is far more successful than delayed treatment.18

HAART has proven very successful in achieving a significant increase in survival and quality of life of HIV-infected individuals, and life expectancy is markedly increased in many individuals using the therapy.2 Not everyone, however, benefits equally from HAART. Survival time is shorter despite HAART in individuals who are injected drug abusers, those with AIDS before initiation of therapy, those with a very high viral load before initiation of therapy (>100,000 copies/ml), those who are inconsistent in adherence to the drug regimen, or those who discontinue the drugs. Other factors that affect life expectancy in the era of HAART include smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, older age at initiation of therapy, comorbidities such as hepatitis C or other viral, bacterial, or fungal infections; chronic liver, kidney, or cardiovascular conditions; and diabetes mellitus. Low socioeconomic status is also a negative factor, perhaps related to access to care, and HIV-related death continues to occur earlier in Hispanics and non-Hispanic Blacks.56,80

Before the advent of antiretroviral therapy, opportunistic infections (OI) were the principal cause of morbidity and mortality among HIV-infected persons. Even today, however, OIs continue to occur among those who are unaware of their HIV infection, those who do not take recommended medications, and those who are resistant or adversely react to recommended medications. In some instances, HAART has not altered the rate of occurrence or severity of certain OIs, although HAART is associated with increased occurrence of others. For example, in the oral cavity, candidal infections are markedly reduced in individuals responsive to antiretroviral therapy,212 as is hairy leukoplakia, Kaposi’s sarcoma, deep mycoses, necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG), and necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP). Conversely, the incidence and severity of oral condylomata and herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection appear unchanged, whereas neutropenia-associated oral aphthous-like ulcers; lichenoid reactions; and oral melanotic macules of the lip, gingiva, palate, or buccal mucosa may increase.196 Based on these observations, the presence or absence of oral opportunistic infections associated with HIV infection or its treatment may serve as markers for success or failure of antiretroviral therapy.*

A newly described phenomenon associated with recovery of immunity with HAART is the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). In this syndrome, infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis, disseminated Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) disease, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and herpes zoster viruses, are reactivated, causing an overwhelming inflammatory response that makes the symptoms of infection more severe. This seems to occur in individuals with low baseline CD4 counts who are responsive to HAART, causing a rapid increase in the CD4 cell numbers and a hyperinflammatory response that may cause fever and worsening of an existing bacterial, viral, or fungal infection.205 In the oral cavity, IRIS lesions could include CMV infection, varicella-zoster virus (VZV) infection, histoplasmosis, cryptococcal infections, and others. IRIS most often occurs within the first 4 to 8 weeks after starting antiretroviral therapy in individuals who had high viral loads and low DC4+ T-lymphocyte counts. The condition is difficult to diagnosis and manage and may take months to subside, but it does not appear to affect patient survival. At this time, the implications of IRIS regarding oral OIs is largely unknown, but parotid enlargement has been reported as a common oral manifestation for reasons that have not yet been elucidated.150,151,175

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

Patients who are positive for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can be managed in the dental office in much the same way as healthy patients with respect to strict infection control measures that follow the guidance of the American Dental Association and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There may be an increased risk of periodontal disease in HIV positive patients, and these patients can exhibit an exaggerated acute inflammation of the gingiva. Necrotizing lesions of the gingiva and periodontium can progress dramatically in HIV positive patients, thus it is necessary to utilize thorough local therapy combined with systemic antibiotics and local use of antimicrobial mouthwashes such as chlorhexidine and meticulous oral hygiene by the patient. HIV positive patients with these lesions should be seen daily until the tissues heal to ensure that the tissue destruction is controlled.

HIV patients can be generally managed with nonsurgical periodontal treatment. In patients with low viral loads and near normal CD4 lymphocyte count, periodontal surgery and implant placement is possible after detailed consultation and clearance from the patient’s physician.

Oral and Periodontal Manifestations of Hiv Infection

Oral lesions are common in HIV-infected patients, although geographic and environmental variables may exist. Previous reports indicated that most AIDS patients have head and neck lesions,181 whereas oral lesions are quite common in HIV-positive individuals who do not yet have AIDS.14,76 Several reports have identified a strong correlation between HIV infection and oral candidiasis, oral hairy leukoplakia, atypical periodontal diseases, oral Kaposi’s sarcoma, and oral non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.55,58,126

Oral lesions less strongly associated with HIV infection include melanotic hyperpigmentation, mycobacterial infections, necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis (NUS), miscellaneous oral ulcerations, and viral infections (e.g., HSV, herpes zoster, and condyloma acuminatum). Lesions seen in HIV-infected individuals but of undetermined frequency include less common viral infections (e.g., CMV, molluscum contagiosum), recurrent aphthous stomatitis, and bacillary angiomatosis (epithelioid angiomatosis).55

The advent of HAART has resulted in greatly diminished frequency of oral lesions associated with HIV infection and AIDS.30,147,212

However, some medical protocols delay the use of HAART drugs until immune suppression is relatively severe. These protocols also discontinue HAART if immune stability has been achieved or if the targeted virus becomes drug resistant.61,138,191,213 In theory, these protocols suggest that HIV/AIDS patients may experience a greater number of oral manifestations than patients who start HAART therapy earlier. The dental practitioner must continue to be prepared to diagnose and manage these conditions in coordination with the patient’s physician. However, HIV resistance to antiretroviral drug therapy is an ongoing problem, and this resistance may even be transmitted to newly infected sexual partners or to newborns of infected mothers.70

Oral Candidiasis

Candida, a fungus found in normal oral flora, proliferates on the surface of the oral mucosa under certain conditions. A major factor associated with overgrowth of Candida is diminished host resistance, as seen in debilitated patients or in patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy. The incidence of candidal infection has been demonstrated to increase progressively in relationship to diminishing immune competency.130,131,206 Most oral candidal infections (85% to 95%) are associated with Candida albicans, but other species of Candida may be involved. Currently, at least 11 strains of Candida have been identified, and non–C. albicans infections are more common among immunocompromised individuals already receiving antifungal therapy for C. albicans.128,194

Candidiasis is the most common oral lesion in HIV diseases and has been found in approximately 90% of AIDS patients.157,203 It usually has one of four clinical presentations: pseudomembranous, erythematous, or hyperplastic candidiasis or angular cheilitis.97,146

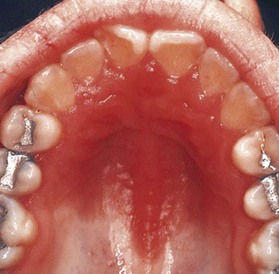

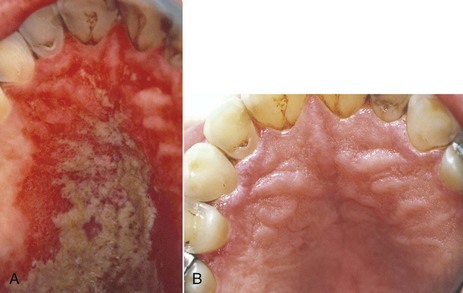

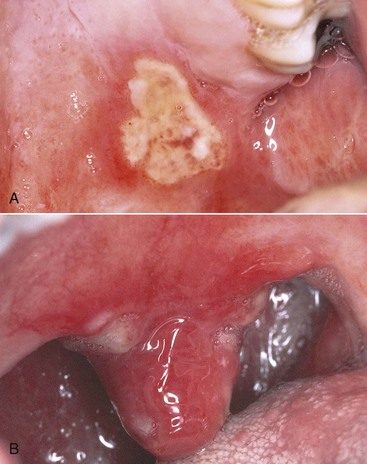

Pseudomembranous candidiasis (“thrush”) presents as painless or slightly sensitive, yellow-white curdlike lesions that can be readily scraped and separated from the surface of the oral mucosa. This type is most common on the hard and soft palate and the buccal or labial mucosa but can occur anywhere in the oral cavity (Figure 19-2).

Erythematous candidiasis may be present as a component of the pseudomembranous type, appearing as red patches on the buccal or palatal mucosa, or it may be associated with depapillation of the tongue. If gingiva is affected, it may be misdiagnosed as desquamative gingivitis (Figures 19-3 to 19-5).

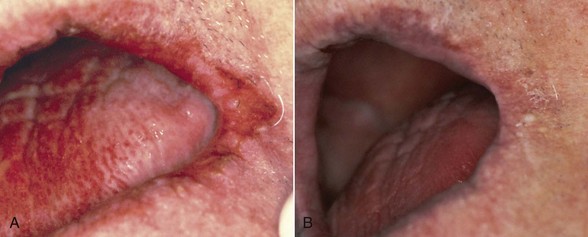

Hyperplastic candidiasis is the least common form and may be seen in the buccal mucosa and tongue. It is more resistant to removal than the other types (Figures 19-6 and 19-7).

Figure 19-7 Hyperplastic candidiasis in corner of mouth. Lesion has persisted despite use of systemic antifungal drugs.

In angular cheilitis the commissures of the lips appear erythematous with surface crusting and fissuring.

Diagnosis of candidiasis is made by clinical evaluation, culture analysis, or microscopic examination of a tissue sample or smear of material scraped from the lesion, which shows hyphae and yeast forms of the organisms (Figure 19-8). When oral candidiasis appears in patients with no apparent predisposing causes, the clinician should be alerted to the possibility of HIV infection.55 Many patients at risk for HIV infection who present with oral candidiasis also have esophageal candidiasis, a diagnostic sign of AIDS.214

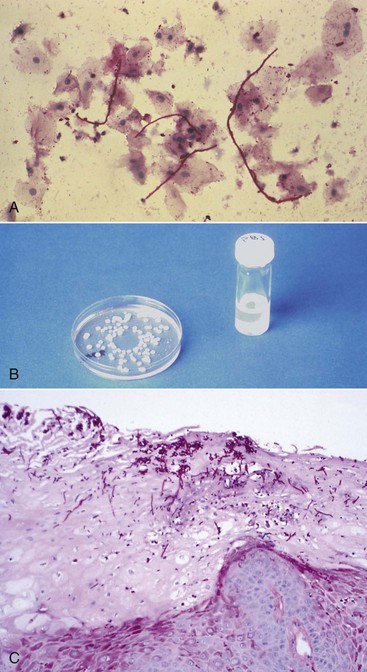

Figure 19-8 Techniques for diagnosis of candidiasis. A, Candidal hyphae in tissue smear after periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining. B, Culture media is specific for Candida species. C, Candidal hyphae in epithelium of biopsied tissue.

Although candidiasis in HIV-infected patients may respond to antifungal therapy, it is often refractory or recurrent. In the past, 30% of patients with AIDS-related candidiasis relapsed within 4 weeks of treatment and 60% to 80% within 3 months. This relapse may have resulted from decreasing immunocompetency or development of antifungal-resistant candidal strains.99 As many as 10% of candidal organisms become resistant to long-term fluconazole therapy, and cross-resistance to other azoles (ketoconazole, itraconazole miconazole, or clotrimazole) and amphotericin B may develop.* Resistant candidiasis is more common in individuals who have low CD4 counts at baseline.99

Recent reports indicate that the administration of HAART in HIV infections has resulted in a significant decrease in incidence of oropharyngeal candidiasis and oral candidal carriage and has reduced the rate of fluconazole resistance.† When esophageal candidiasis is present during HAART, there is an increased incidence of nonalbicans species and fluconazole-resistant organisms.214 Early oral lesions of HIV-related candidiasis are usually responsive to topical antifungal therapy (Figure 19-9). More advanced lesions, including hyperplastic candidiasis, may require systemic antifungal drugs; systemic therapy is mandatory for esophageal candidiasis193,200 (Figure 19-10).

Figure 19-9 Palatal pseudomembranous candidiasis. A, Before treatment with nystatin oral suspension. B, Remission after 2 weeks of treatment.

Figure 19-10 Severe angular cheilitis. A, Before treatment. B, After treatment with systemic fluconazole.

†References 29, 46, 54, 128, 144, 147, 178. With any therapy, lesions tend to recur after the drug is discontinued, and resistant strains of candidal organisms have been described, especially with the use of systemic agents.50,193,223 Box 19-3 identifies therapeutic agents often prescribed for treatment of candidal infections. Most oral topical antifungal agents contain large quantities of sucrose, which may be cariogenic after long-term use. For this reason, some authorities recommend oral use of vaginal tablets because they do not contain sucrose. However, such tablets are relatively low in active units (100,000) compared with usual oral dosages of 200,000 to 600,000 units. Sucrose-free nystatin is also available in a powder form, which may be mixed extemporaneously with water at each use (teaspoon powder to glass water). Additionally, many compounding pharmacies can provide a sucrose-free nystatin on request. Recently, sucrose-free oral suspensions of itraconazole and amphotericin B oral rinse have become available. To date, few comparative studies have been performed regarding the effectiveness of these products. Amphotericin B oral suspension is more effective against C. albicans than other species. Patients should be instructed to rinse with the oral suspension for several minutes, then swallow.167 Fluconazole oral suspension has been reported to be more effective as an antifungal than liquid nystatin. Chlorhexidine and cetylpyridinium chloride oral rinses may also be of some prophylactic value against oral candidal infection.71 Long-term prophylactic effectiveness of once-weekly systemic fluconazole also has been described.193

BOX 19-3 Common Antifungal Therapeutic Agents for Oral Candidiasis

U, Units; qid, four times daily; tid, three times daily; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

Systemic antifungal agents, such as ketoconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B, are effective in treatment of oral candidiasis152 (see Box 19-3). Fluconazole may be the agent of choice when systemic therapy is required.5,49,199,203 As previously mentioned, however, resistant strains of candidal organisms may develop with prolonged use of any systemic agent, potentially rendering the drugs ineffective against life-threatening candidal infections in the later stages of immunosuppression.26,172 In addition, significant adverse side effects may occur with long-term use of any systemic antifungal agent. For example, long-term use of ketoconazole may induce liver damage in individuals with preexisting liver disease. The increased risk of chronic hepatitis B or hepatitis C infection in immunosuppressed individuals may put some patients at risk for ketoconazole-induced liver damage. If ketoconazole is prescribed, patients should receive liver function tests at baseline and at least monthly during therapy. The drug is contraindicated if the patient’s aspartate transaminase (AST) level is greater than 2.5 times normal.220 Ketoconazole absorption also may be impaired by the gastropathy experienced by many HIV-infected individuals.115

Oral Hairy Leukoplakia

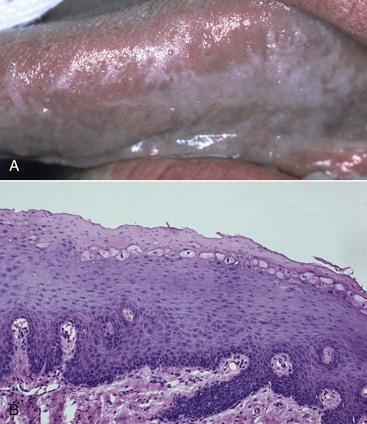

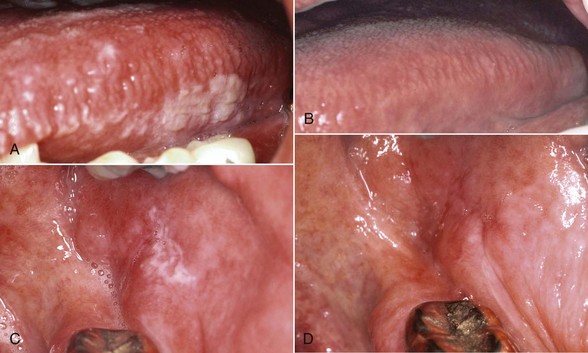

Oral hairy leukoplakia (OHL) primarily occurs in persons with HIV infection.84,87 Found on the lateral borders of the tongue, OHL frequently has a bilateral distribution and may extend to the ventrum. This lesion is characterized by an asymptomatic, poorly demarcated keratotic area ranging in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters (Figure 19-11, A). Often, characteristic vertical striations are present, imparting a corrugated appearance, or the surface may be shaggy and appear “hairy” when dried. The lesion does not rub off and may resemble other keratotic oral lesions.

Figure 19-11 Oral hairy leukoplakia on left lateral border of tongue. A, Clinical view. B, Biopsy confirmation of oral hairy leukoplakia. Note the ballooned epithelial cells near the surface of the epithelium.

Microscopically, the OHL lesion shows a hyperparakeratotic surface with projections that often resemble hairs. Beneath the parakeratotic surface, acanthosis and some characteristic “balloon cells” resembling koilocytes are seen (Figure 19-11, B). It has been demonstrated that these cells contain viral particles of the human herpesvirus group; these particles have been interpreted as the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV).84,88

Epithelial dysplasia is not a feature, and in most OHL lesions, little or no inflammatory infiltrate in the underlying connective tissue is present.190

OHL is found almost exclusively on the lateral borders of the tongue, although it has been reported on the dorsum of the tongue, buccal mucosa, floor of the mouth, retromolar area, and soft palate.59,84,111 In addition, most of these lesions reveal surface colonization by Candida organisms, which are secondary invaders and not the cause of the lesion.

OHL was originally believed to be caused by the human papillomavirus, but subsequent evidence indicated an association with EBV.59,84,86,228 In the late 1980s, so-called pseudo–hairy leukoplakia was described in HIV-negative and EBV-negative individuals with lesions clinically identical to OHL. In addition, several case reports have described OHL in EBV-infected but HIV-negative individuals with a variety of immunosuppressed conditions (e.g., acute myelogenous leukemia) or who develop immunosuppression as a result of organ transplantation or extensive systemic corticosteroid therapy.86,210 Regardless of cause, biopsy identification of a lesion suggestive of OHL should dictate that HIV testing be performed. It should be emphasized that the severity of the lesion is not correlated with the likelihood of developing AIDS; thus small lesions are as diagnostically significant as extensive lesions.190

The differential diagnosis of OHL includes several white lesions of the mucosa, such as dysplasia, carcinoma, frictional and idiopathic keratosis, lichen planus, tobacco-related leukoplakia, secondary syphilis, psoriasiform lesions (e.g., geographic tongue), and hyperplastic candidiasis.3,155 The microscopic confirmation of OHL of the tongue in a high-risk patient is considered to be a specific early sign of HIV infection and an indication that the patient will develop AIDS.87,183 Before the advent of effective therapy for HIV, survival analysis indicated that 83% of HIV-infected patients with hairy leukoplakia would develop AIDS within 31 months, and the number of patients with hairy leukoplakia who eventually developed AIDS approached 100%.87 Use of HAART, however, has resulted in a greatly diminished incidence of OHL16,30,61,213,229 (Figure 19-12).

Figure 19-12 A, Oral hairy leukoplakia of tongue before initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). B, Oral hairy leukoplakia of buccal mucosa before initiating HAART. C, Tongue lesion in remission after initiation of HAART. D, Remission of lesion on buccal mucosa after HAART.

If OHL occurs despite HAART, it may represent an increasing immunodeficiency resulting from therapeutic failure, failure to take medications as prescribed, or reduced dosage of medications to prevent adverse side effects.58 Vigorous treatment of OHL is usually not indicated. However, the lesions are often responsive to HIV drug therapy or the use of antiviral agents such as acyclovir, desciclovir, ganciclovir, foscarnet, or valacyclovir.229,231 Lesions can be successfully removed with laser or conventional surgery. Some have advocated the topical application of podophyllin, retinoids, oral acyclovir, or interferon, but these agents can induce unwanted local or systemic side effects. Regardless of the choice of treatment, OHL lesions tend to recur when therapy is discontinued.5,228,229

Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Other Malignancies

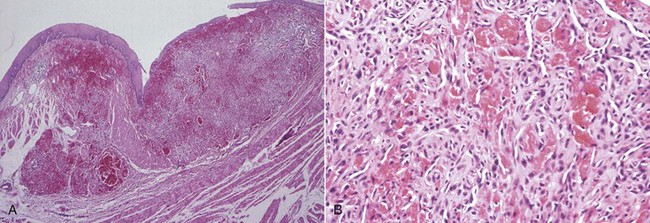

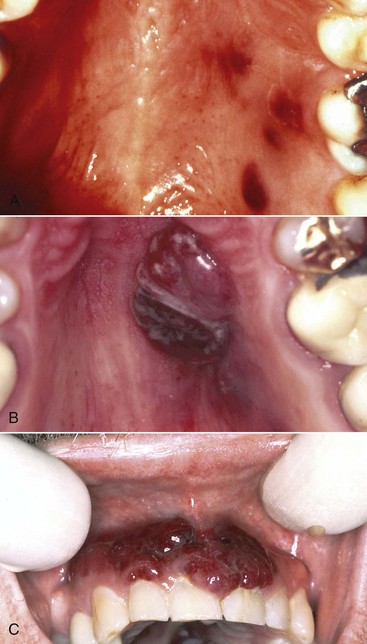

Oral malignancies occur more frequently in severely immunocompromised individuals than in the general population. An HIV-positive individual with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) or Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is categorized as having AIDS (Figure 19-13). Oral lesions are reported in approximately 4% of individuals with NHL, and the gingiva and palate are common sites. The incidence of oral squamous cell carcinoma may also increase in HIV-infected individuals.19 KS was a very rare disease until the early 1980s. In its classic form, it is found in older men, occasionally in postorgan transplant individuals, and it is endemic in parts of Africa. An epidemic form has subsequently been described in HIV-positive individuals, and it is an AIDS-defining condition.156

KS is the most common oral malignancy associated with AIDS. This angioproliferative tumor is a rare, multifocal, vascular neoplasm; it was originally described in 1872 as occurring in the skin of the lower extremities of older men of Mediterranean origin. Today it is closely associated with homosexual and heterosexual transmission but occurs five to ten times more often in male homosexuals than in other HIV high-risk groups. The causative agent has been identified as human herpesvirus-8 (HHV-8).

As far as is known, HHV-8 seroconversion precedes development of epidemic KS by 5 to 10 years. It has been associated with both AIDS-related and non–AIDS-related KS.67,181 However, untreated HIV-infected individuals are 7000-fold more likely to develop KS.2 HHV-8 seroconversion is common, and the virus has been isolated from 29% of American adults and 8% of children in the non-AIDS general population. It has also been isolated from lesions of NHL, Castleman’s disease, other lymphoproliferative disorders, and a variety of additional abnormalities, although these findings may coincide with those of the healthy general population.79,106,204 In contrast, one study identified HHV-8 in over 90% of HIV-related and non–HIV-related KS lesions.113 Thus it appears that decreasing immunocompetence results in activation of latent HHV-8. As mentioned, the virus may be sexually transmitted, but it may also be transmitted from infected mothers to children.195,211

Although KS is a malignant tumor, in its classic and endemic forms, it is a localized and usually slowly growing lesion. The KS that occurs in HIV-infected patients presents different clinical features (Figures 19-14 and 19-15). In these individuals, KS is a much more aggressive lesion, and the majority (71%) develop lesions of the oral mucosa, particularly the palate and gingiva.109 (Figure 19-16). The oral cavity may often be the first or only site of the lesion.11

Figure 19-16 Intraoral Kaposi’s sarcoma. A, Multiple painless, nonelevated palatal lesions. B, Palatal Kaposi’s lesion that interfered with function and required treatment. C, Gingival lesion that created an esthetic concern for the patient.

In the early stages the oral lesions are painless, reddish-purple macules of the mucosa. As they progress, the lesions frequently become nodular and can easily be confused with other oral vascular entities such as hemangioma, hematoma, varicosity, or pyogenic granuloma (when occurring in the gingiva).195

Lesions may manifest as nodules, papules, or nonelevated macules that are usually brown, blue, or purple, although occasionally the lesions may display normal pigmentation. Diagnosis is based on histologic findings.176

Microscopically, Kaposi’s sarcoma consists of four components: (1) endothelial cell proliferation with the formation of atypical vascular channels; (2) extravascular hemorrhage with hemosiderin deposition; (3) spindle cell proliferation in association with atypical vessels; and (4) a mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate consisting mainly of plasma cells82 (Figure 19-17).

Regional and gender differences are apparent; oral KS is more common in the United States than in Europe, and the male/female ratio is 20 : 1.216 KS has also been reported in patients with lupus erythematosus who are receiving immunosuppressant therapy, as well as in renal transplant patients and other individuals receiving corticosteroid or cyclosporine therapy. Case reports describe gingival KS in HIV-negative patients experiencing cyclosporine-induced gingival enlargement.170,221 In an HIV-positive individual, the presence of KS signifies transition to outright AIDS. Before the advent of combined drug therapy for AIDS, the median survival time after onset of KS ranged from 7 to 31 months.43

The differential diagnosis of oral KS includes pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, atypical hyperpigmentation, sarcoidosis, bacillary angiomatosis, angiosarcoma, pigmented nevi, and cat-scratch disease (skin).181

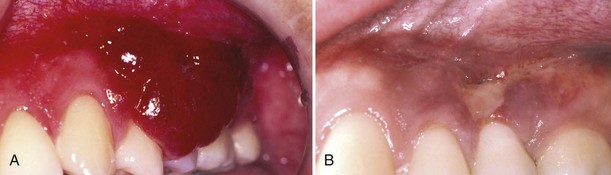

The advent of HAART has resulted in a marked reduction in the incidence of KS. However, the lesions may still be found in severely immunocompromised individuals or those who are unaware of their HIV-positive status.67 HHV-8 may be found more frequently in saliva of HIV-positive individuals with higher CD4 cell counts, suggesting that viral shedding may occur relatively early in the disease process.43,100 Treatment of oral KS includes antiretroviral agents, laser excision, cryotherapy, radiation therapy, and intralesional injection with vinblastine, interferon-gamma, sclerosing agents, or other chemotherapeutic drugs.5,58,200,216 Nichols et al145 described the successful use of intralesional injections of vinblastine at a dose of 0.1 mg/cm2 using a 0.2 mg/ml solution of vinblastine sulfate in saline (Figure 19-18). In responsive patients, treatment was repeated at 2-week intervals until resolution or stabilization of the lesions. Side effects included some posttreatment pain and occasional ulceration of the lesions, but in general the therapy was well tolerated. Total resolution was achieved in 70% of 82 intraoral KS lesions with 1 to 6 treatments. Lesions tended to recur, however, indicating that treatment probably should be reserved for oral KS lesions that are easily traumatized or that interfere with chewing or swallowing. Occasionally, treatment may be indicated when KS lesions create an unsightly appearance on the lips or in the anterior oral cavity. In a double-blind, randomized clinical trial on a small group of patients with oral KS lesions, the authors concluded that vinblastine injections remain the most effective treatment in managing localized lesions.172 However, comparable results may be obtained using injections of 3% sodium tetradecyl sulfate, a sclerosing agent, previously used in treatment of varicose veins. The sclerosing agent offers the advantage of being relatively inexpensive and easy to use. Destructive periodontitis has also been reported in conjunction with gingival KS. In such patients, scaling and root planing and other periodontal therapy may be indicated in addition to intralesional or systemic chemotherapy.200,216

Figure 19-18 A, Management of gingival Kaposi’s sarcoma interfering with function. B, Nearly complete resolution of the lesion after intralesional injection with vinblastine.

The incidence of KS in HIV-positive individuals has decreased precipitously since its peak in 1989, partially as the result of the emphasis on safer sexual practices, as well as the introduction of HAART. Today, AIDS-related KS is uncommon except in those who are unaware of their HIV-positive status, those who are not taking HAART, or those who have discontinued HAART for one reason or another.23,130

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma

Lymphoma represents a heterogeneous malignancy characterized by proliferation of lymphoid cells. It is broadly classified as Hodgkin’s disease (14%) or non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL). NHL in individuals with HIV infection is an AIDS-defining condition, and elevated cumulative viremia may be a strong predictor of AIDS-related lymphoma.239

Risk of NHL is associated with a number of infections and EBV-associated lesions include Burkitt’s lymphoma and HIV-associated lymphoma. However, the role of the virus in tumor formation has not been clarified, and a viral etiology has not been confirmed. NHL is characterized by malignancy of B or T lymphocytes, and tumors are typed by the WHO classification system as indolent, aggressive, or highly aggressive. NHL is treated by chemotherapy, and HAART does not appear to reduce the incidence or prognosis of the malignancies, although HIV-associated NHL may be less common.129

Oral lesions usually appear as erythematous, painless enlargements that may become ulcerated because of traumatic injury (Figure 19-19). In some cases, bone involvement occurs, although this is rare in the United States. Diagnosis is based on physical examination, complete blood count with differential, imaging studies, and lymph node and tissue biopsy.141

Patients with HIV and benign lymphoepithelial involvement of the salivary glands may have a markedly increased risk of developing benign or malignant lymphoma.58

AIDS patients with NHL may require management of HIV-related OIs, chemotherapy-induced mucositis and thrombocytopenia, and possibly graft-versus-host disease, if hematopoietic cell transplantation is performed.58,129

Bacillary (Epithelioid) Angiomatosis

Bacillary (epithelioid) angiomatosis (BA) is an infectious vascular proliferative disease with clinical and histologic features similar to those of KS. BA is believed to be transmitted by a cat scratch and caused by rickettsia-like organisms (e.g., Bartonella henselae and Bartonella quintana).55,173,188

It can occur in immunocompetent persons but is most commonly associated with AIDS. Skin lesions are similar to those seen in KS or cat-scratch disease. Gingival BA manifests as red, purple, or blue edematous soft tissue lesions that may cause destruction of periodontal ligament and bone74 (see Figure 19-19).

The condition is more prevalent in HIV-positive individuals with low CD4 levels.136

Diagnosis of bacillary angiomatosis is based on biopsy, which reveals an “epithelioid” proliferation of angiogenic cells accompanied by an acute inflammatory cell infiltrate. The causative organism in the biopsy specimen may be identified using Warthen-Starry silver staining or electron microscopy.69

Differential diagnosis of BA includes KS, angiosarcoma, hemangioma, pyogenic granuloma, and nonspecific vascular proliferation.38 Bacillary angiomatosis is usually treated using broad-spectrum antibiotics such as erythromycin or doxycycline. Gingival lesions may be managed using the antibiotic in conjunction with conservative periodontal therapy and possibly excision of the lesion.38,74,75,178 To date, no reports have been found regarding the effect of HAART on BA incidence in HIV-positive individuals.

Oral Hyperpigmentation

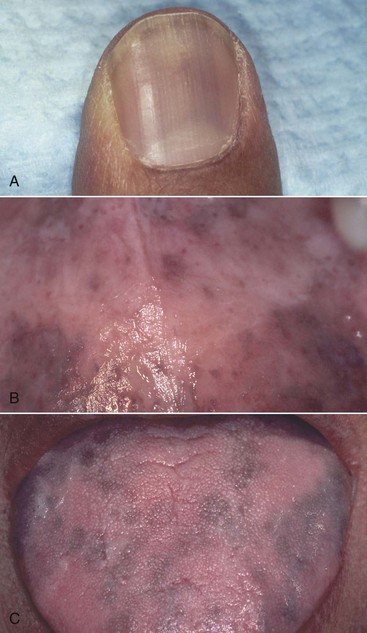

An increased incidence of oral hyperpigmentation has been described in HIV-infected individuals.41,114,117,238 Oral pigmented areas often appear as spots or striations on the buccal mucosa, palate, gingiva, or tongue (Figure 19-20).

Figure 19-20 Drug-induced hyperpigmentation (zidovudine). A, Fingernail bed discoloration. B, Same patient, palatal hyperpigmentation. C, Same patient, tongue hyperpigmentation. Note similarity between the oral lesions and those caused by adrenal cortex hypofunction (Addison’s disease).

In some cases, the pigmentation may relate to prolonged use of drugs such as zidovudine, ketoconazole, or clofazimine.238 Zidovudine is also associated with excessive pigmentation of the skin and nails, although similar hyperpigmentation has been reported in some individuals who have never taken zidovudine. On occasion, oral pigmentation may be the result of adrenocorticoid insufficiency induced in an HIV-positive individual by prolonged use of ketoconazole or by Pneumocystis jiroveci infection or CMV or other viral infections117 (see Figure 19-20).

Atypical Ulcers

Atypical ulcers (nonspecific oral ulcerations) in HIV-infected individuals may have multiple etiologies that include neoplasms such as lymphoma, KS, and squamous cell carcinoma. HIV-associated neutropenia may also feature oral ulcerations.

Neutropenia has been successfully treated using recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) with resultant resolution of oral ulcers.121 Severe, prolonged oral ulcers have been successfully managed using prednisone or thalidomide, a drug that inhibits tissue necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). Recurrence is likely, however, if either drug is discontinued.79,108

HIV-infected patients have a higher incidence of recurrent herpetic lesions and aphthous stomatitis (Figures 19-21 and 19-22).

Figure 19-21 Abnormal herpetic lesions in HIV-positive individuals. A, Lip crusting of primary herpetic gingivostomatitis. B, Same patient, ulcerations of gingiva, alveolar mucosa, and vestibule. C, Severe herpes labialis in commissures of lip. D, Close-up view of herpes labialis. Note fluid-filled vesicles.

Figure 19-22 Intraoral aphthous stomatitis in AIDS patient. A, Major aphthous lesion in left soft palate. B, Same patient, ulcerations of uvula.

Approximately 10% of HIV-infected patients have herpes infection,161 and multiple episodes are common. The CDC HIV classification system indicates that mucocutaneous herpes lasting longer than 1 month is diagnostic of AIDS in HIV-infected individuals.32 Aphthae and aphthae-like lesions are common when patients are followed throughout the course of their immunosuppression.76

In healthy patients, herpetic and aphthous lesions are self-limiting and relatively easy to diagnose by their characteristic clinical features (i.e., herpes on the keratinizing mucosa, aphthae on the nonkeratinizing surfaces). In HIV-infected patients, the clinical presentation and course of these lesions may be altered. Herpes may involve all mucosal surfaces and extend to the skin and may persist for months60 (see Figure 19-21). Atypical large, persistent, nonspecific, and painful ulcers are common in immunocompromised individuals. If healing is delayed, these lesions are secondarily infected and may become indistinguishable from persistent herpetic or aphthous lesions.178

A wide variety of bacterial and viral infections may produce severe oral ulcerations in HIV-infected individuals.211 Essentially, immunocompromised individuals are at risk from infectious agents endemic to the patient’s geographic location. Atypical or nonhealing ulcers may require biopsy, microbial cultures, or both to determine the etiology. Oral ulcerations have been described in association with enterobacterial organisms such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter cloacae, and Escherichia coli.178 Such infections are rare and are usually associated with systemic involvement. Specific antibiotic therapy is indicated, and close coordination of oral therapy with the patient’s physician is usually necessary.178

HSV, VZV, EBV, and CMV are frequently retrieved from nonspecific oral ulcers, indicating a possible etiologic role.211 Recently, some atypical ulcers were found to be co-infected with HSV and CMV or with EBV and CMV.180,217 These ulcers may be more common in individuals who are neutropenic in conjunction with their HIV infection. Neutropenia may also be induced by drugs such as zidovudine, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and gancyclovir.121 Atypical ulcers may be more severe and persistent in individuals with low CD4 cell counts, and the presence of oral CMV-induced ulcers may be indicative of systemic CMV infection.76

Herpes labialis in HIV-infected individuals may be responsive to topical antiviral therapy (e.g., acyclovir, penciclovir, or docosanol), reducing the healing time of lesions. In other patients, however, oral or labial herpetic lesions may require the use of systemic antiviral agents (e.g., acyclovir, valacyclovir, or famciclovir).6,57,60

Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) has been described in HIV-infected individuals, but the overall incidence may be no greater than that in the general population.55 RAS may occur, however, as a component of the initial acute illness of HIV seroconversion. The incidence of major aphthae may be increased, and the oropharynx, esophagus, or other areas of the gastrointestinal tract may be involved6 (see Figure 19-22).

Available evidence indicates that the incidence of herpes virus infections is not reduced by HAART while the incidence of neutropenic ulcerations may actually increase.

Proven methods of treatment for recurrent aphthous stomatitis include topical or intralesional corticosteroids, chlorhexidine or other antimicrobial mouth rinses, oral tetracycline rinses, or topical amlexanox. Systemic corticosteroid therapy may be necessary in some cases. Consequently, in patients with HIV infection and recurrent aphthae, closely coordinated medical and dental therapy may be necessary.57,60

Recent evidence indicates that many nonspecific oral ulcerations may be of viral origin, with HSV, EBV, and CMV being most common76 (Figure 19-23). For this reason, the practitioner should consider viral culturing of such lesions and the use of antiviral agents in treatment where appropriate.

Oral viral infections in immunocompromised individuals are often treated with acyclovir (200–800 mg administered 5 times daily for at least 10 days). Subsequent daily maintenance therapy (200 mg 2 to 5 times daily) may be required to prevent recurrence. Resistant viral strains are treated with foscarnet, ganciclovir, or valacyclovir.5,214

Topical corticosteroid therapy (fluocinonide gel applied 3 to 6 times daily) is safe and efficacious for treatment of recurrent aphthous ulcers or other mucosal lesions in immunocompromised individuals.57 However, topical corticosteroids may predispose immunocompromised individuals to candidiasis. Consequently, prophylactic antifungal medications should be prescribed.

Occasionally, large aphthae in HIV-positive individuals may prove resistant to conventional topical therapy. In these patients, medical consultation is recommended, and administration of systemic corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone 40 to 60 mg daily) or alternative therapy (e.g., thalidomide, levamisole, or pentoxifylline) should be considered.37,105 These agents may have significant side effects, however, and the clinician should remain alert for any evidence suggestive of an adverse drug reaction or interaction with currently prescribed medications.55 Because virtually all antiviral agents used in treatment of HIV infection have the potential for adverse side effects or drug interactions, the dental clinician should consider topical therapy when appropriate.

Salivary Gland Disorders and Xerostomia

Saliva is an important component of the oral mucosal immune system containing many HIV inhibitors such as HIV-1 specific antibodies, lysozyme, peroxidases, cystatins, lactoferrin, histatins, and others9,201 Saliva also may contain a specific salivary anti-HIV factor, secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor. Its immune properties plus its flushing action may help to explain why HIV concentrations are low in saliva and why the oral cavity is rarely a site of HIV transmission. Conversely, dryness of the mouth (xerostomia) is common in HIV-positive individuals and worsens as the viral load increases to more than 100,000 copies per mm3. In addition, enlargement of the major salivary glands, particularly the parotids, is more common in HIV-positive individuals.120

Salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia may be most common in HIV-infected men in both early and advanced stages of HIV infection and immunosuppression.

Salivary function does not appear to be affected by HAART despite the fact that some individual antiretroviral medications are reported to induce xerostomia. However, it is clear that xerostomia is a relatively common condition among HIV-infected individuals and up to 10% may be affected. Xerostomia appears to become more severe as immunosuppression worsens and increased candidal carriage is associated with reduced salivary flow rate.107 One longitudinal study indicated that submandibular/sublingual hypofunction occurs earlier than parotid hypofunction, but the parotid glands become progressively less functional over time.

Reports concerning a possible interrelationship between salivary gland function and HIV infection have been difficult to assess because there is little standardization of protocols to study salivary hypofunction and many medications used in treatment of HIV infection and associated conditions may induce xerostomia. Despite these limitations, a carefully conducted study of xerostomia in HIV-positive and HIV-negative women indicated that HIV-positive individuals were nearly three times as likely to have zero unstimulated salivary flow rate as HIV-negative individuals. Zero unstimulated salivary flow rate was significantly associated with a CD4 count <200, but no differences were found relative to viral load.142

Although some antiretroviral medications are reported to contribute to xerostomia, the overall effect of antiretroviral therapy may indicate that the drugs serve to prevent salivary gland hypofunction by controlling HIV replication.142 Parotid enlargement associated with HIV infection may occur as the result of a condition described as diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis syndrome, which is characterized by persistent circulating CD8+ lymphocytosis and visceral lymphocytic infiltration and parotid infiltration. Other causes include cystic lymphoepithelial lesions, hyperplastic lymphadenopathy, bacterial and viral Infections, Sjögren’s syndrome, and lymphoma.62 Additionally, HAART is associated with lipodystrophy syndrome that may result in fat hypertrophy in the parotid glands in association with facial thinning and visceral fatty deposits. This syndrome is associated with dyslipidemia and increased insulin resistance.124

Dental Treatment Complications

Concerns have been expressed regarding the potential for postoperative complications (hemorrhage, infection, or delayed wound healing) in individuals with HIV/AIDS. Medically compromised patients must be carefully managed in the dental office to avoid undue treatment complications.48 However, systematic reviews of the literature indicate that special precautions are usually not necessary based simply on the HIV status of patients when performing periodontal treatment procedures such as dental prophylaxis, scaling and root planing, periodontal surgery, extractions, and placement of implants. On occasion, however, the poor overall health status of an individual with AIDS may limit periodontal therapy to conservative, minimally invasive procedures, and antibiotic therapy may be required.8,51,52,73,158 When possible, antibiotics should be avoided in significantly immunocompromised individuals to minimize the risk of OIs (i.e., candidiasis), superinfection, and microorganism drug resistance.140

Adverse Drug Effects

A number of adverse drug-induced effects have been reported in HIV-positive patients, and the dentist may be the first to recognize an oral drug reaction. Foscarnet, interferon, and 2-3-dideoxycytidine (DDC) occasionally induce oral ulcerations, and erythema multiforme has been reported with use of didanosine (DDI).45 Zidovudine and ganciclovir may induce leukopenia, resulting in oral ulcers.133 Xerostomia and altered taste sensation have been described in conjunction with diethyldithiocarbamate (Ditiocarb). HIV-positive patients are believed to be generally more susceptible to drug-induced mucositis and lichenoid drug reactions than the general population.12,45,135 In some patients, mouth ulcers and mucositis resolve if drug therapy is continued beyond 2 to 3 weeks, but when drug effects are severe or persistent, alternative therapy with different drugs should be used.

HAART drugs may induce adverse side effects ranging from relatively mild conditions, such as nausea, to the development of kidney stones. Individuals with hepatitis and HIV co-infection are susceptible to liver cirrhosis.177 A newly identified adverse effect is lipodystrophy, a condition that features the redistribution of body fat. Affected individuals may develop gaunt facial features yet display excessive abdominal fat or even a fat pad on the rear of the shoulders (buffalo hump). This may be accompanied by severe systemic hyperlipidemia.* Other adverse effects of HAART include increased insulin resistance,94 gynecomastia,125 toxic epidermal necrolysis, blood dyscrasias,194 and possibly increased incidence of oral warts.24,83,180,227 Other reported oral or perioral adverse effects include oral lichenoid reactions, xerostomia, altered taste sensation, perioral paresthesia, and exfoliative cheilitis21,22,27,137 (Figures 19-24 and 19-25).

Gingival and Periodontal Diseases

Considerable research has focused on the nature and incidence of periodontal diseases in HIV-infected individuals. Some studies suggest that chronic periodontitis is more common in this patient population, but others do not. Periodontal diseases are more common among HIV-infected users of injection drugs, but this may relate to poor oral hygiene and lack of dental care rather than decreased CD4 cell counts.89,116,161 However, some unusual types of periodontal diseases do seem to occur with greater frequency in HIV-positive individuals.

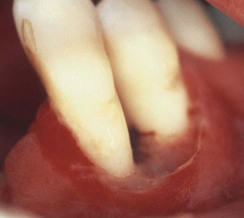

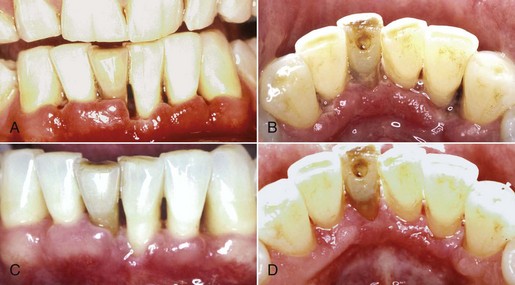

Linear Gingival Erythema

A persistent, linear, easily bleeding, erythematous gingivitis has been described in some HIV-positive patients. Linear gingival erythema (LGE) may or may not serve as a precursor to rapidly progressive NUP75,77 (Figures 19-26 and 19-27). The microflora of LGE may closely mimic that of periodontitis rather than gingivitis. However, candida infection has been implicated as a major etiologic factor, and human herpesviruses have been proposed as possible triggers or cofactors.5,44,184,207,218 Linear gingivitis lesions may be localized or generalized in nature. The erythematous gingivitis (1) may be limited to marginal tissue, (2) may extend into attached gingiva in a punctate or a diffuse erythema, or (3) may extend into the alveolar mucosa.

Figure 19-26 Linear gingival erythema (LGE) and necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) in AIDS patient.

LGE is sometimes unresponsive to corrective therapy, but such lesions may undergo spontaneous remission. Concomitant oral candidiasis and LGE lesions have been identified, suggesting a possible etiologic role for candidal species in LGE.116 In one study, direct microscopic cultures from LGE lesions implicated Candida dubliniensis in four patients, all of whom experienced complete or partial remission after systemic antifungal therapy.223 It is not yet known whether candidal infections are etiologic in all LGE cases. A recent systematic review indicates that LGE is more common among HIV-infected populations but that most individuals who are HIV positive do not experience LGE.157

LGE-like lesions can often be adequately managed by following the therapeutic principles associated with marginal gingivitis. However, it has been suggested that gingivitis lesions that respond to conventional therapy do not represent LGE.215 The affected sites should be scaled and polished. Subgingival irrigation with chlorhexidine or 10% povidone-iodine may be beneficial. The patient should be carefully instructed in performance of meticulous oral hygiene procedures. The condition should be reevaluated 2 to 3 weeks after initial therapy. If the patient is compliant with home care procedures and the lesions persist, the possibility of a candidal infection should be considered. It is doubtful that topical antifungal rinses will reach the base of the gingival crevices. Consequently, the treatment of choice may be the empiric administration of a systemic antifungal agent, such as fluconazole, for 7 to 10 days.98

It is important to remember that LGE may be refractory to treatment. If so, the patient should be carefully monitored for developing signs of more severe periodontal conditions (e.g., NUG, NUP, or NUS). The patient should be placed on a 2- to 3-month recall maintenance interval and re-treated as necessary. As mentioned, despite the occasional resistance of LGE to conventional periodontal therapy, spontaneous remission may occur for reasons that are not yet known.

Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis

Some reports have described an increased incidence of NUG among HIV-infected individuals, although this has not been substantiated by other studies.53,76,77,101,186,209

There is no consensus on whether the incidence of necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) increases in HIV-positive patients.155,158,177,197 However, a recent study evaluated the HIV status of individuals who presented with necrotizing periodontal diseases, and 69% were found to be HIV seropositive.197 Treatment of NUG in these patients does not differ from that in HIV-negative individuals (see Chapter 41).

The affected gingiva may be exquisitely painful, and caution must be taken to avoid undue patient discomfort.

Basic treatment may consist of cleaning and debridement of affected areas with a cotton pellet soaked in peroxide after application of a topical anesthetic. Escharotic oral rinses, such as hydrogen peroxide, should only rarely be used, however, for any patient and are especially contraindicated in immunocompromised individuals. The patient should be seen daily or every other day for the first week, and debridement of affected areas is repeated at each visit. Plaque control methods are gradually introduced. A meticulous plaque control program should be taught and started as soon as the sensitivity of the area allows it. After initial healing has occurred, the patient should be able to tolerate scaling and root planing if needed.

The patient should avoid tobacco, alcohol, and condiments. An antimicrobial oral rinse, such as chlorhexidine gluconate 0.12%, is prescribed.

Systemic antibiotics, such as metronidazole or amoxicillin, may be prescribed for patients with moderate-to-severe tissue destruction, localized lymphadenopathy or systemic symptoms, or both. Metronidazole may be the antibiotic of choice, since it has been demonstrated to be effective in NUG treatment and its narrow bactericidal spectrum may minimize the risk of secondary opportunistic infections such as candidiasis.235 The use of prophylactic antifungal medication should be considered if antibiotics are prescribed.

The periodontium should be reevaluated 1 month after resolution of acute symptoms to assess the results of treatment and determine if further therapy will be necessary.

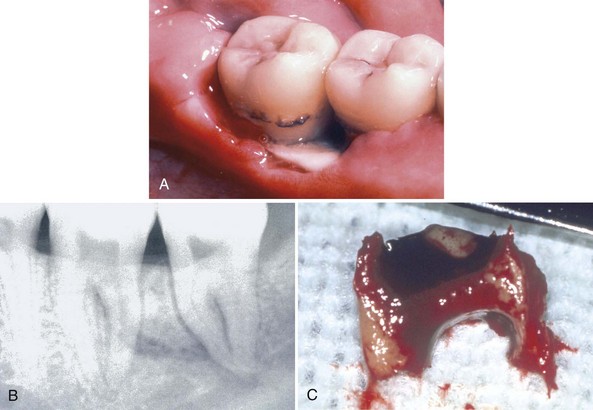

Necrotizing Ulcerative Periodontitis

A necrotizing, ulcerative, rapidly progressive form of periodontitis occurs more frequently among HIV-positive individuals, although such lesions were described long before the onset of the AIDS epidemic. Necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP) may represent an extension of NUG in which bone loss and periodontal attachment loss occur.148,197

NUP is characterized by soft tissue necrosis, rapid periodontal destruction, and interproximal bone loss77,166 (Figures 19-28, 19-29, and 19-30). Lesions may occur anywhere in the dental arches and are usually localized to a few teeth, although generalized NUP is sometimes present after marked CD4+ cell depletion. Bone is often exposed, resulting in necrosis and subsequent sequestration. NUP is severely painful at onset, and immediate treatment is necessary. Occasionally, however, patients undergo spontaneous resolution of the necrotizing lesions, leaving painless, deep interproximal craters that are difficult to clean and that may lead to conventional periodontitis.75

Figure 19-29 NUP in otherwise healthy 19-year-old male patient who was HIV negative. A, Anterior maxilla. B, Palatal view.

Figure 19-30 Early NUP in patient with AIDS. A, Facial view. B, Lingual view. C, Complete resolution of NUP after treatment, facial view. D, Lingual view.

Some evidence suggests slight differences between the microbial flora found in NUP lesions and that found in chronic periodontitis,140,154 but most data implicate a similar microbial component in both diseases. An increasing number of studies, however, have identified the presence of candidal organisms and human herpesviruses of various types in individuals with necrotizing ulcerative periodontal diseases. The exact role for these organisms is not yet fully understood.42,207 As discussed earlier, the reported periodontal health of HIV-infected individuals is subject to wide variations.182,234 Riley et al182 examined 200 HIV-positive patients and found that 85 were periodontally healthy; none had NUG; 59 had gingivitis; 54 were experiencing mild, moderate, or advanced periodontitis; and only two had NUP. Glick et al77 reported the prevalence of NUP as 6.3% in an HIV-positive population and described a positive correlation with the presence of NUP and outright AIDS.77

Therapy for NUP includes local debridement, scaling and root planing, in-office irrigation with an effective antimicrobial agent, such as chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone-iodine (Betadine), and establishment of meticulous oral hygiene, including home use of antimicrobial rinses or irrigation.158,165,187

This therapeutic approach is based on reports involving only a small number of patients.

In severe NUP, antibiotic therapy may be necessary but should be used with caution in HIV-infected patients to avoid an opportunistic and potentially serious, localized candidiasis or even candidal septicemia.166 If an antibiotic is necessary, metronidazole (250 mg, with 2 tablets taken immediately and then 2 tablet 4 times daily for 5 to 7 days) is the drug of choice. Prophylactic prescription of a topical or systemic antifungal agent is prudent if an antibiotic is used.

Necrotizing Ulcerative Stomatitis

Necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis (NUS) has occasionally been reported in HIV-positive patients. NUS may be severely destructive and acutely painful and may affect significant areas of oral soft tissue and underlying bone. It may occur separately or as an extension of NUP101,165 and is often associated with severe suppression of CD4 immune cells and elevated viral load. The condition appears to be identical to cancrum oris (noma), a rare destructive process reported in nutritionally deprived individuals, especially in Africa. NUS may be associated with severe immunodeficiency regardless of the cause of onset.7,15,183

Treatment for NUS may include an antibiotic, such as metronidazole, and use of an antimicrobial mouth rinse such as chlorhexidine gluconate. If osseous necrosis is present, it is often necessary to remove the affected bone to promote wound healing7 (Figure 19-31).

Chronic Periodontitis

A number of longitudinal or prevalence studies have suggested that HIV-positive individuals are more likely to experience chronic periodontitis than the general population.10,134,143,174 Most studies, however, do not take into account the level of oral hygiene or the degree of immunodeficiency in the population studied or whether the individuals in the study are injection drug users (IDUs); these confounding factors cloud the issue.

EBV-1 has been reported to be present more frequently in HIV-positive patients than in HIV-negative patients.81 Lamster et al116 compared frequency of oral lesions and periodontal diseases between HIV-positive and HIV-negative individuals, some of whom were IDUs. They concluded that the lifestyle of IDUs may play a larger role in oral disease than the individual’s HIV status. They also found that tongue lesions consistent with hairy leukoplakia were most common among seropositive homosexual males, whereas oral candidiasis and LGE were most common among IDUs.

Others have reported that the incidence and severity of chronic periodontitis are similar in HIV-positive and HIV-negative groups.185,187 Klein et al112 evaluated heterosexuals with AIDS and found a larger percentage of women (91%) than men (73%) with gingivitis or periodontitis. Overall, most heterosexuals with AIDS had only gingivitis (70%), whereas others had moderate (27%) to severe (27%) periodontitis. This study suggests that periodontal diseases are no more frequent in heterosexuals with AIDS than the general population. The finding of more frequent disease in women may reflect more women with AIDS being IDUs.

Drinkard et al53 evaluated the periodontal status of asymptomatic HIV-positive individuals and those with signs and symptoms of declining immune status. They reported that both groups were generally in good periodontal health, with no significant differences between groups. Others have described similar findings.180,184,185,187,189

A well-controlled study indicated that gingival recession and early attachment loss are more common in HIV groups than matched groups from the general population.184 This appears to affirm that immunocompromised individuals are slightly more susceptible to chronic periodontitis than those with a robust immune system. In support of this Ceballos-Salobrena et al30 reported a 30% decrease in the prevalence of chronic periodontitis in AIDS patients receiving HAART. The majority of HIV-positive individuals experience gingivitis and chronic periodontitis in a manner similar to the general population. However, several studies have suggested that proinflammatory cytokines are increased in HIV-positive individuals, which suggest that chronic periodontitis may tend to be more severe in this population should it be present.235

With proper home care and appropriate periodontal treatment and maintenance, HIV-positive individuals can anticipate reasonably good periodontal health throughout the course of their disease.110 The median period between initial HIV infection and outright AIDS is approximately 15 years, and the life expectancy of persons living with AIDS has been significantly prolonged with current anti-HIV drug therapy.20,34

This indicates that HIV-infected patients are potential candidates for conventional periodontal treatment procedures including periodontal surgery and implant placement. Treatment decisions should be based on the overall health status of the patient, the degree of periodontal involvement, and the motivation and ability of the patient to perform effective oral hygiene (Figure 19-32).

Clearly, some less common periodontal diseases do occur more frequently in HIV-positive individuals, but these same conditions are also reported among HIV-negative persons. Consequently, definitions for these conditions and discussion of their management should not be construed as limiting them to individuals with HIV or AIDS.

Periodontal Treatment Protocol

It is imperative that medically compromised patients, including those with HIV or AIDS, be safely and effectively managed in dental practice.198 Several universal treatment considerations are important to ensure that this is achieved.

Health Status

The patient’s health status should be determined from the health history, physical evaluation, and consultation with the patient’s physician. Treatment decisions will vary depending on the patient’s state of health. For example, delayed wound healing and increased risk of postoperative infection are possible complicating factors in AIDS patients, but neither concern should significantly alter treatment planning in an otherwise healthy, asymptomatic, HIV-infected patient with a normal or near-normal CD4 count and a low viral bioload.68,92,126,168

It is important to obtain information regarding the patient’s immune status with questions such as the following:

Infection Control Measures

Clinical management of HIV-infected periodontal patients requires strict adherence to established methods of infection control, based on guidance from the American Dental Association (ADA) and the CDC. Compliance, especially with universal precautions, will eliminate or minimize risks to patients and the dental staff.68,123,224 Immunocompromised patients are potentially at risk for acquiring as well as transmitting infections in the dental office or other health care facility.119,139,149

Goals of Therapy

A thorough oral examination will determine the patient’s dental treatment needs.

The primary goals of dental therapy should be the restoration and maintenance of oral health, comfort, and function. At the very least, periodontal treatment goals should be directed toward control of HIV-associated mucosal diseases such as chronic candidiasis and recurrent oral ulcerations. Acute periodontal and dental infections should be managed, and the patient should receive detailed instructions in performance of effective oral hygiene procedures.73,98