CHAPTER 41 Treatment of Acute Gingival Disease

The treatment of acute gingival disease entails the alleviation of the acute symptoms and elimination of all other periodontal disease, both chronic and acute, throughout the oral cavity. Treatment is not complete if periodontal pathologic changes or factors capable of causing them are still present.

Acute Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis

Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG) results from an impaired host response to a potentially pathogenic microflora. Depending on the degree of immunosuppression, NUG may occur in a mouth essentially free of other gingival involvement or may be superimposed on underlying chronic gingival disease. Treatment should include the alleviation of the acute symptoms and the correction of the underlying chronic gingival disease. The former is the simpler part of the treatment, whereas the latter requires more comprehensive procedures.

The treatment of NUG consists of (1) alleviation of the acute inflammation by reducing the microbial load and removal of necrotic tissue, (2) treatment of chronic disease either underlying the acute involvement or elsewhere in the oral cavity, (3) alleviation of generalized symptoms such as fever and malaise, and (4) correction of systemic conditions or factors that contribute to the initiation or progression of the gingival changes. Chapter 19 provides further information on the management and treatment of NUG in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Treatment of NUG should follow an orderly sequence, according to specific steps at three clinical visits.

First Visit

At the first visit, the clinician should do a complete evaluation of the patient, including a comprehensive medical history with special attention to recent illness, living conditions, dietary background, cigarette smoking, type of employment, hours of rest, risk factors for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and psychosocial parameters (e.g., stress, depression). The patient is questioned regarding the history of the acute disease and its onset and duration, as follows:

The clinician should also inquire as to the type of treatment received and the patient’s impression regarding its effect.

The examination of the patient should include general appearance, presence of halitosis, presence of skin lesions, vital signs including temperature, and palpation for the presence of enlarged lymph nodes, especially submaxillary and submental nodes.

The oral cavity is examined for the characteristic lesion of NUG (see Chapters 10 and 17), its distribution, and the possible involvement of the oropharyngeal region. Oral hygiene is evaluated, with special attention to the presence of pericoronal flaps, periodontal pockets, and local factors (e.g., poor restorations, distribution of calculus). Periodontal probing of NUG lesions is likely to be very painful and may need to be deferred until after the acute lesions are resolved.

The goals of initial therapy are to reduce the microbial load and remove necrotic tissue to the degree that repair and regeneration of normal tissue barriers are reestablished. Treatment during this initial visit is confined to the acutely involved areas, which are isolated with cotton rolls and dried. A topical anesthetic is applied, and after 2 or 3 minutes the areas are gently swabbed with a moistened cotton pellet to remove the pseudomembrane and nonattached surface debris. Bleeding may be profuse. Each cotton pellet is used in a small area, then discarded; sweeping motions over large areas with a single pellet are not recommended. After the area is cleansed with warm water, the superficial calculus is removed. Ultrasonic scalers are very useful for this purpose because they do not elicit pain, and the water jet and cavitation aid in lavage of the area.

Subgingival scaling and curettage are contraindicated at this time because these procedures may extend the infection into the deeper tissues and may also cause bacteremia. Unless an emergency exists, procedures, such as extractions or periodontal surgery, are postponed until the patient has been symptom free for 4 weeks, to minimize the likelihood of exacerbating the acute symptoms.

Patients with moderate or severe NUG and local lymphadenopathy or other systemic signs or symptoms are placed on an antibiotic regimen of amoxicillin, 500 mg orally every 6 hours for 10 days. For amoxicillin-sensitive patients, other antibiotics are prescribed, such as erythromycin (500 mg every 6 hours) or metronidazole (500 mg twice daily for 7 days). Systemic complications should subside in 1 to 3 days. Antibiotics are not recommended in NUG patients who do not have systemic complications.

Instructions to the Patient

The patient is discharged with the following instructions:

Patients are asked to report back to the clinician in 1 to 2 days. The patient should be advised of the extent of total treatment that the condition requires and warned that treatment is not complete when pain stops. The patient should be informed of the presence of chronic gingival or periodontal disease, which must be eliminated to reduce the likelihood of recurrence of the acute symptoms.

A large variety of drugs have been used in the treatment of NUG.3 Topical drug therapy, however, is only an adjunctive measure; no drug, when used alone, can be considered complete therapy. Systemic antibiotics, when used, also reduce the oral bacterial flora and alleviate the oral symptoms,11,12 but they are only an adjunct to the complete local treatment that the disease requires. In patients treated by drugs alone or by systemic antibiotics alone the acute painful symptoms often recur after treatment is discontinued.

Second Visit

At the second visit, 1 or 2 days after the first visit, the patient is evaluated for amelioration of signs and symptoms. The patient’s condition is usually improved; the pain is diminished or no longer present. The gingival margins of the involved areas are erythematous but without a superficial pseudomembrane.

Scaling is performed if necessary and sensitivity permits. Shrinkage of the gingiva may expose previously covered calculus, which is gently removed. The instructions to the patient are the same as those given previously.

Third Visit

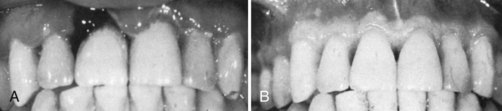

At the next visit, approximately 5 days after the second visit, the patient is evaluated for resolution of symptoms, and a comprehensive plan for the management of the patient’s periodontal conditions is formulated. The patient should be essentially symptom free. Some erythema may still be present in the involved areas, and the gingiva may be slightly painful on tactile stimulation (Figure 41-1, A). The patient is instructed in plaque control procedures (see Chapter 44), which are essential for the success of the treatment and the maintenance of periodontal health. The patient is further counseled on nutrition, smoking cessation, and other conditions or habits associated with a potential recurrence. The hydrogen peroxide rinses are discontinued, but chlorhexidine rinses can be maintained for 2 or 3 weeks. Scaling and root planing are repeated if necessary. Unfortunately, the patient often discontinues treatment because the acute condition has subsided; however, this is when comprehensive treatment of the patient’s chronic periodontal problem should start.

Figure 41-1 Initial response to treatment of patient with acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG). A, Severe acute NUG. B, Third day after treatment. Patient still has some erythema, but the condition is greatly improved.

Appointments should be scheduled for the treatment of chronic gingivitis, periodontal pockets, and pericoronal flaps, as well as for the elimination of all forms of local irritation. The patient should be reevaluated at 1 month to determine compliance with oral hygiene, health habits, psychosocial factors, the potential need for reconstructive or esthetic surgery, and the interval of subsequent recall visits.

Gingival Changes with Healing

The characteristic lesion of NUG undergoes the following changes in the course of healing in response to treatment:

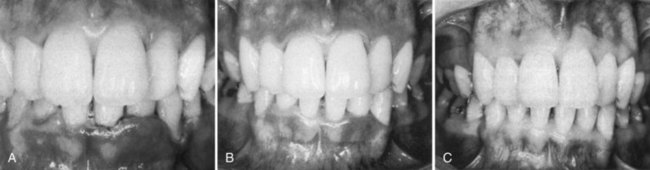

Figure 41-2 Treatment of acute NUG. A, Before treatment. Note the characteristic interdental lesions. B, After treatment, showing restoration of healthy gingival contour.

Figure 41-3 Physiologic contour and new attachment of gingiva after treatment of acute NUG. A, Acute NUG showing the characteristic punched-out eroded gingival margin with surface pseudomembrane. B, After treatment. Note the restoration of physiologic gingival contour and reattachment of the gingiva to the surfaces of the mandibular teeth, which had been exposed by the disease.

Additional Treatment Considerations

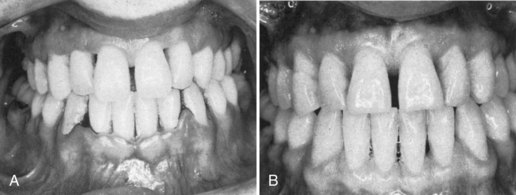

Contouring of Gingiva as Adjunctive Procedure

Even in cases of severe gingival necrosis, healing often leads to restoration of the normal gingival contour, although normal architecture of the gingiva may be achieved only after several weeks or months (Figure 41-4). However, if there has been loss of interdental bone, if the teeth are irregularly aligned, or if the entire papilla is lost, healing sometimes results in the formation of a shelflike gingival margin, which favors retention of plaque and recurrence of gingival inflammation as well as being an esthetic problem. This can be corrected by an attempt to restore lost tissue through periodontal plastic procedures or by reshaping the gingiva surgically (Figure 41-5). Effective plaque control by the patient is particularly important to establish and maintain the normal gingival contour in areas of tooth irregularity.

Role of Drugs

A large variety of drugs have been used for topical treatment of NUG. Topical drug therapy is only an adjunctive measure. No drug, when used alone, can be considered complete treatment.

Escharotic drugs, such as phenol, silver nitrate, chromic acid, or potassium bichromate, should not be used. They are necrotizing agents that alleviate pain by destroying the nerve endings of the ulcerated gingiva. However, they also destroy young cells needed for repair and delay healing. Repeated use of these agents results in loss of gingival tissue that is not restored when the disease subsides.4

Persistent or Recurrent Cases

Adequate local therapy with optimal home care will resolve most cases of NUG. If a case of NUG persists despite therapy or if it recurs, the patient should be reevaluated, with a focus on the following factors:

The clinician should evaluate the quality and consistency of plaque control. Further assessment and counseling on tobacco use will also determine the role of tobacco in this patient. If the clinician perceives that psychosocial factors are unresolved and are complicating health behaviors and contributing to immunosuppression, the patient should be referred to the appropriate professional. A reassessment of the patient’s nutritional state, with potential dietary analysis or nutritional testing, may be required.5,7

Acute Pericoronitis

The treatment of pericoronitis depends on the severity of the inflammation, the systemic complications, and the advisability of retaining the involved tooth. All pericoronal flaps should be viewed with suspicion. Persistent symptom-free pericoronal flaps should be removed as a preventive measure against subsequent acute involvement.

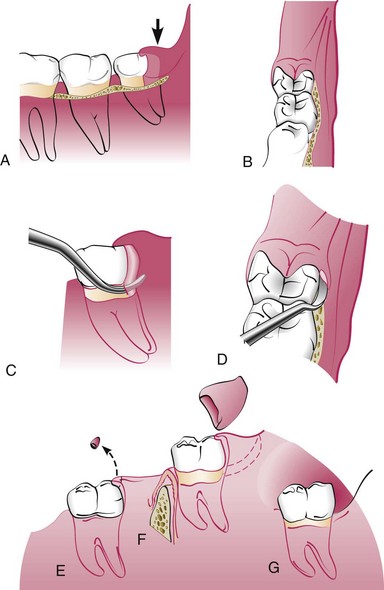

The treatment of acute pericoronitis consists of (1) gently flushing the area with warm water to remove debris and exudate and (2) swabbing with antiseptic after elevating the flap gently from the tooth with a scaler. The underlying debris is removed, and the area is flushed with warm water (Figure 41-6). The occlusion is evaluated to determine if an opposing tooth is occluding with the pericoronal flap. It may be necessary to reduce soft tissue surgically and/or to adjust the opposing tooth to alleviate pain. Antibiotics can be prescribed in severe cases and for patients who may have clinical evidence of diffuse microbial infiltration of the tissue. If the gingival flap is swollen and fluctuant, an incision may be necessary to establish drainage and relieve pressure.

Figure 41-6 Treatment of acute pericoronitis. A, Inflamed pericoronal flap (arrow) in relation to the mandibular third molar. B, Anterior view of third molar and flap. C, Lateral view with scaler in position to gently remove debris under flap. D, Anterior view of scaler in position. E, Incorrect removal of the tip of the flap, permitting the deep pocket to remain distal to the molar. F, Removal of section of the gingiva distal to the third molar, after the acute symptoms subsided. The line of incision is indicated by the broken line. G, Appearance of the healed area.

Once the acute symptoms have subsided, the prognosis of the tooth can be evaluated. The decision will be governed by the likelihood of whether the tooth will continue eruption into a functional position or if impaction and the factors predisposing to pericoronitis will persist. Bone loss on the distal surface of the second molar is a concern when third molars are impacted along the distal surface.2 The problem is significantly greater if the third molars are extracted after the roots are formed or when patients are older (i.e., mid-twenties or later). To reduce the risk of bone loss around second molars, partially or completely impacted third molars should be extracted early in their development.

If the decision is made to retain the tooth, the pericoronal flap is surgically reduced (see Figure 41-6). It is necessary to remove the tissue distal to the tooth, as well as the flap on the occlusal surface. Incising only the occlusal portion of the flap leaves a deep distal pocket, which invites recurrence of acute pericoronal involvement. It is critical to leave the patient with a cleansable site. On healing, the patient needs appropriate instruction in long-term maintenance.

Acute Herpetic Gingivostomatitis

Primary infection with herpes simplex virus in the oral cavity results in a condition known as acute herpetic gingivostomatitis, which is an oral infection often accompanied by systemic signs and symptoms (see Chapter 10). This infection typically occurs in children, but it can occur in adults as well. It runs a 7- to 10-day course and usually heals without scarring. A recurrent herpetic episode may be precipitated in individuals with a history of herpesvirus infections by dental treatment,13 respiratory infections, sunlight exposure, fever, trauma, exposure to chemicals, and emotional stress.

Treatment consists of early diagnosis and immediate initiation of antiviral therapy. Until recently, therapy for primary herpetic gingivostomatitis consisted of palliative care. With the development of antiviral therapy, however, the standard of care has changed. in a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study, Amir et al1 demonstrated that antiviral therapy with 15 mg/kg of an acyclovir suspension given 5 times daily for 7 days substantially changes the course of the disease without significant side effects. Acyclovir reduced symptoms, including fever, from 3 days to 1 day; decreased new extraoral lesions from 5.5 to 0 days; and reduced difficulty with eating from 7 to 4 days. Furthermore, viral shedding stopped at 1 day for the acyclovir group compared with 5 days for the control group. Overall, oral lesions were present for only 4 days in the acyclovir group but for 10 days in the control group. Although no clear clinical evidence indicates that this regimen will reduce recurrences, research data suggest that a greater number of latent virus copies incorporated into ganglia will increase the severity of recurrences.1

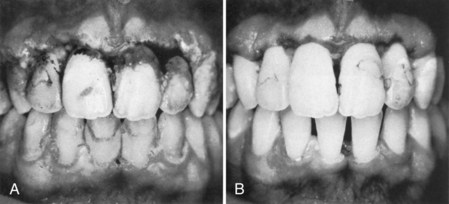

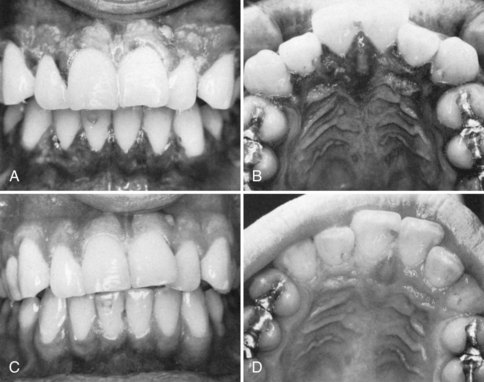

In summary, if primary herpetic gingivostomatitis is diagnosed within 3 days of onset, acyclovir suspension should be prescribed: 15 mg/kg 5 times daily for 7 days. If diagnosis occurs after 3 days in an immunocompetent patient, acyclovir therapy may have limited value. All patients, including those presenting more than 3 days after disease onset, may receive palliative care, including removal of plaque and food debris. An NSAID (e.g., ibuprofen) can be given systemically to reduce fever and pain. Patients may use either nutritional supplements or topical anesthetics (e.g., viscous lidocaine) before eating to aid in proper nutrition during the early phases in acute herpetic gingivostomatitis. Periodontal therapy should be postponed until the acute symptoms subside to avoid the possibility of exacerbation (Figure 41-7).

Figure 41-7 Treatment of acute herpetic gingivostomatitis. A, Before treatment. Note diffuse erythema and surface vesicles. B, Before treatment, palatal view, showing gingival edema and ruptured vesicle on palate. C, One month after treatment, showing restoration of normal gingival contour and stippling. D, One month after treatment, palatal view.

Local or systemic application of antibiotics is sometimes advised to prevent opportunistic infection of ulcerations, especially in the immunocompromised patient. If the condition does not resolve within 2 weeks, the patient should be referred to a physician for medical consultation.6 The patient should be informed that herpetic gingivostomatitis is contagious at certain stages such as when vesicles are present (highest viral titer). All individuals exposed to an infected patient should take precautions. Herpetic infection of a clinician’s finger, referred to as herpetic whitlow, can occur if a seronegative clinician becomes infected with a patient’s herpetic lesions.9,10

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

These patients have pain as an important symptom and so need to be treated promptly and need to be contacted day by day to ensure they are comfortable. Necrotizing gingivitis is treated with local root planing, oral hygiene instruction, and oral antimicrobial rinses. Systemic antibiotics are only used if there is evidence of lymphadenopathy or spread beyond the gingiva, except they are always used in immunocompromised patients such as those diagnosed as HIV positive.

It is important to correctly diagnose painful gingiva due to herpetic gingivostomatitis as these patients do not need antimicrobial therapy but instead antiviral medications such as acyclovir are used topically or, in severe cases, systemically. These patients are infectious while they have lesions and so they need to limit close direct contact of their mouth with other people to avoid transmission.

Acute gingival lesions that do not respond to treatment within 2 weeks should be biopsied to secure the correct diagnosis.

1 Amir J, Harel L, Smetana Z, Varsano I. Treatment of herpes simplex gingivostomatitis with acyclovir in children: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study. BMJ. 1997;314:1800.

2 Ash MMJr, Costich ER, Hayward JR. A study of periodontal hazards of third molars. J Periodontol. 1962;33:209.

3 Burket LW. Oral medicine, ed 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1946.

4 Glickman I, Johannessen LB. The effect of a six percent solution of chromic acid on the gingiva of the albino rat: a correlated gross, biomicroscopic, and histologic study. J Am Dent Assoc. 1950;41:674.

5 King JD. Nutritional and other factors in “trench mouth” with special reference to the nicotinic acid component of the vitamin B2 complex. Br Dent J. 1943;74:113.

6 Langlais RP, Miller CS. Color atlas of common oral diseases, ed 2. New York: Williams & Wilkins; 1998.

7 Linghorne WJ, McIntosh WG, Tice JW, et al. The relation of ascorbic acid intake to gingivitis. J Can Dent Assoc. 1946;12:49.

8 Mitchell DF, Baker BR. Topical antibiotic control of necrotizing gingivitis. J Periodontol. 1968;39:81.

9 Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ. Oral pathology: clinical-pathologic correlations. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1989.

10 Snyder ML, Church DH, Rickles NH. Primary herpes infection of right second finger. Oral Surg. 1969;27:598.

11 Wade AB, Blake G, Mirza K. Effectiveness of metronidazole in treating the acute phase of ulcerative gingivitis. Dent Pract. 1966;16:440.

12 Wade AB, Blake GC, Manson JD, et al. Treatment of the acute phase of ulcerative gingivitis (Vincent’s type). Br Dent J. 1963;115:372.

13 Williamson RT. Diagnosis and management of recurrent herpes simplex induced by fixed prosthodontic tissue management: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent. 1999;82:1.