CHAPTER 55 Conscious Sedation

Periodontal and implant surgery should be performed painlessly and with minimal or no apprehension. The patient should be assured of this at the outset and throughout the procedure. The most reliable means of providing painless surgery is with effective administration of local anesthesia. However, patients who are apprehensive may require treatment under mild or moderate sedation. The use of sedation can help make patients more comfortable during periodontal and implant surgery, especially when the procedure is expected to continue for 2 hours or more. Routes of administration for sedation agents include inhalation, oral, intramuscular, and intravenous (IV). The specific agent(s) and modality of administration are based on the desired level of sedation, anticipated length of the procedure, overall condition of the patient, and training of the clinician and staff. This chapter reviews the rationale, definitions, techniques, and guidelines for the use of mild-to-moderate conscious sedation in the dental office for periodontal and implant surgical procedures.

Rationale for Sedation During Periodontal and Implant Surgical Procedures

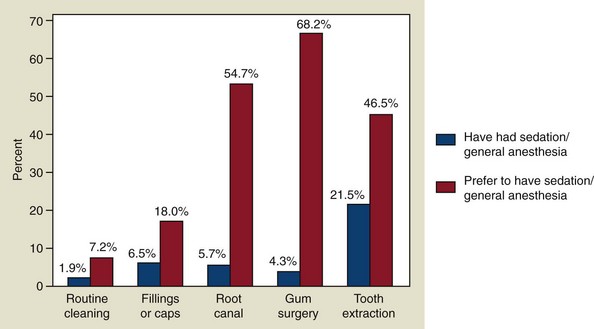

Many patients delay or avoid having needed dental treatment because of fear and anxiety. This avoidance behavior often results in compromised health and quality of life. Anxiety toward dental therapy has not changed significantly over the past 50 years; publications report that about 30% to 50% of patients are at least somewhat fearful of dental procedures.7,13,14,53 New evidence suggests that genetic variations are associated with anxiety related to dental care, which could help to explain the consistent avoidance patterns despite improved treatment methods.8 According to a national survey of the Canadian population, more than 68% of patients would prefer to have sedation or general anesthesia for periodontal surgery9 (Figure 55-1). Anxiety reduction is an important part of delivering advanced periodontal services.49 Furthermore, since dental anxiety results in avoidance behavior and is associated with more dental and periodontal problems,18,38 it is likely that a disproportionate number of patients referred to periodontal specialists will have dental anxiety. Interestingly, there appears to be a close relationship between anxiety and postoperative pain. In fact, preoperative anxiety may be considered a predictor of postoperative pain.20,23 In addition, high levels of anxiety (stress) can affect wound healing after periodontal treatment34,37,58 (see Chapter 27). Sedation techniques have been shown to be effective in reducing physiologic markers of stress.51 For these reasons, it is important for clinicians who provide advanced periodontal and implant therapy to be knowledgeable and skilled in providing sedation in order to reduce anxiety in their patients.

ADA Policy Statement and Guidelines for Conscious Sedation

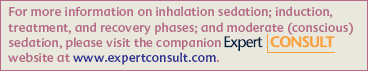

In 2007, the American Dental Association (ADA) released three documents related to the use of sedation and general anesthesia in dentistry. One of these documents, the ADA Guidelines for the Use of Sedation and General Anesthesia in Dentistry, adopted the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ definitions for levels of sedation (Figure 55-2) and specifically related them to use in dentistry.

Figure 55-2 Continuum of depth of sedation: definition of general anesthesia and levels of sedation/analgesia.

(Approved by the ASA House of Delegates on October 27, 2004 and last amended on October 21, 2009. http://www.asahq.org/publicationsAndServices/standards/20.pdf is reprinted with permission of the American Society of Anesthesiologists, 520 N. Northwest Highway, Park Ridge, Illinois 60068-2573.)

ADA Policy Statement and Guidelines for Conscious Sedation

In 2007, the American Dental Association (ADA) released three documents related to the use of sedation and general anesthesia in dentistry, including (1) the ADA Policy Statement: The Use of Sedation and General Anesthesia by Dentists,5 (2) the ADA Guidelines for the Use of Sedation and General Aesthesia by Dentists,4 and (3) ADA Guidelines for Teaching Pain Control and Sedation to Dentists and Dental Students.3 The ADA Policy Statement and the ADA Guidelines provide educational and practice standards for anxiety control in dental practice. The ADA Committee on Anesthesiology, consisting of representatives from dental organizations involved with sedation and anesthesia (Table 55-1), produced these documents after review of the relevant scientific evidence, expert opinion, and comment by all communities of interest. The following paragraphs describe the important elements of these documents as they relate to treating anxious periodontal patients.

TABLE 55-1 American Dental Association Committee on Anesthesiology: 2007 Policy and Guidelines

ADA Policy Statement: The Use of Sedation and General Anesthesia by Dentists

The dental profession’s continued ability to control anxiety and pain effectively depends on a strong educational foundation in the discipline. Training to competency in minimal and moderate sedation techniques may be acquired at the predoctoral, postgraduate, graduate, or continuing education level. Dentists who wish to utilize minimal or moderate sedation are expected to successfully complete formal training, which is structured in accordance with the ADA Guidelines for Teaching Pain Control and Sedation for Dentists and Dental Students.3 The knowledge and skills required for administration of deep sedation and general anesthesia are beyond the scope of predoctoral and continuing education. Only dentists who have completed an advanced education program accredited by the Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) that provides training in deep sedation and general anesthesia are considered educationally qualified to use these modalities in practice.

ADA Guidelines for the Use of Sedation and General Anesthesia by Dentists

Unlike previous ADA documents, the 2007 ADA Guidelines refer to the effects of sedation on the central nervous system and are not dependent on the route of administration. The ADA adopted the American Society of Anesthesiologists definitions for levels of sedation (Figure 55-2) and expanded and commented on them specifically as they relate to treating dental patients.1

Definitions and Levels of Sedation

Pediatric Sedation

Children (aged 12 and under) can become moderately sedated despite an intended level of minimal sedation. The use of preoperative sedatives for children (ages 12 and under) except in extraordinary situations must be avoided because of the risk of unobserved respiratory obstruction during transport by untrained individuals. The management of children with conscious sedation is beyond the scope of this chapter and is not be covered. For children 12 years of age and under, the reader is referred to the American Academy of Pediatrics/American Academy of Pediatric Dentists Guidelines for Monitoring and Management of Pediatric Patients During and After Sedation for Diagnostic and Therapeutic Procedures.2

Adult Sedation

Minimal Sedation

Minimal sedation is defined as a minimally depressed level of consciousness produced by a pharmacologic method that retains the patients ability to independently and continuously maintain an airway and to respond normally to tactile stimulation and verbal command. Although cognitive function and coordination may be modestly impaired, respiratory and cardiovascular functions are unaffected. When the intent is minimal sedation, the appropriate initial dosing of a single enteral drug is no more than the maximum recommended dose of a drug that can be prescribed for unmonitored home use.

Inhalation sedation with nitrous oxide/oxygen (N2O/O2) may be used in combination with a single enteral drug in minimal sedation. It is important to recognize that N2O/O2, when used in combination with one or more sedative agent(s), is capable of producing sedation that is minimal, moderate, or deep and in some cases may produce general anesthesia.

Maximum Recommended Dose

The maximum recommended dose (MRD) is the maximum Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-recommended dose of a drug as printed in FDA-approved labeling for unmonitored home use.

Incremental Dosing

Incremental dosing is the administration of multiple doses of a drug until a desired effect is reached.

Supplemental Dosing

During minimal sedation, supplemental dosing is a single additional dose of the sedative drug being used that may be necessary for prolonged procedures. The supplemental dose should not exceed one-half of the initial total dose and should not be administered until the dentist has determined that the clinical half-life of the initial dose has passed. The total aggregate dose must not exceed 1.5 times the MRD on the day of treatment.

Moderate Sedation

Moderate sedation is a drug-induced depression of consciousness during which patients respond purposefully to verbal commands, either alone or accompanied by light tactile stimulation. No interventions are required to maintain a patent airway, and spontaneous ventilations are adequate. Cardiovascular function is usually maintained. In accord with this particular definition, the drugs and/or techniques used should carry a margin of safety wide enough to render unintended loss of consciousness unlikely. Repeated dosing of an agent before the effects of previous dosing can be fully appreciated may result in greater alteration of the state of consciousness than is the intent of the dentist. Further, a patient whose only response is reflex withdrawal from a painful stimulus is not considered to be in a state of moderate sedation.

Titration

Titration is the administration of incremental doses of a drug until a desired effect is reached. Knowledge of each drug’s time of onset, peak response, and duration of action is essential to avoid oversedation. The concept of titration to effect is critical for patient safety. Thus it is important to know whether the previous dose has taken full effect before administering an additional drug increment when the intent is moderate sedation.

Deep Sedation

Deep sedation is a drug-induced depression of consciousness during which patients cannot be easily aroused but respond purposefully following repeated or painful stimulation. The ability to independently maintain respiratory function may be impaired. Patients may require assistance in maintaining a patent airway, and spontaneous ventilation may be inadequate. Cardiovascular function is usually maintained.

General Anesthesia

General anesthesia is a drug-induced loss of consciousness during which patients are not aroused, even by painful stimulation. The ability to independently maintain respiratory function is often impaired. Patients often require assistance in maintaining a patent airway, and positive pressure ventilation may be required because of depressed spontaneous ventilation or drug-induced depression of neuromuscular function. Cardiovascular function may be impaired.

Clinical Guidelines for Minimal and Moderate Sedation

The following clinical guidelines apply to both minimal and moderate sedation.4 These guidelines include (1) patient evaluation, (2) preoperative preparation, (3) personnel and equipment, (4) monitoring and documentation, and (5) recovery and discharge. Differences between guidelines for minimal and moderate sedation are indicated as appropriate.

Patient Evaluation

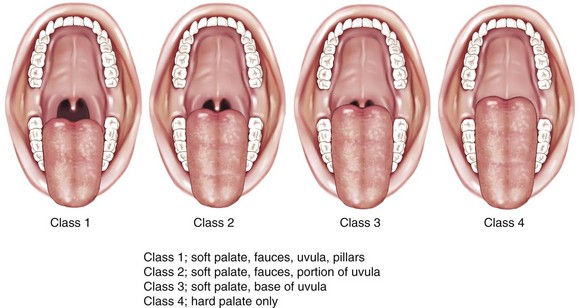

Patients must be evaluated to assess their current health status before any sedation procedure. This should include a determination of their American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status (Table 55-2). In healthy or medically stable individuals (ASA I or II), a review of their medical history and medication use may be adequate. However, for patients with significant medical considerations (ASA III or IV), a consultation with their primary care physician or consulting medical specialist is indicated. The evaluation should also include baseline vital signs and a focused physical examination of alertness, respiratory function, airway, and appearance, as well as a specific evaluation of any identified medical conditions (Box 55-1 and Figure 55-3).

TABLE 55-2 ASA Physical Status Classification System

| ASA 1 | A normal healthy patient. |

| ASA 2 | A patient with mild systemic disease. |

| ASA 3 | A patient with severe systemic disease. |

| ASA 4 | A patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life. |

| ASA 5 | A moribund patient who is not expected to survive without the operation. |

| ASA 6 | A declared brain-dead patient whose organs are being removed for donor purposes. |

From American Society of Anesthesiologists: ASA Physical Status Classification System, www.asahq.org, 2009.

Preoperative Preparation

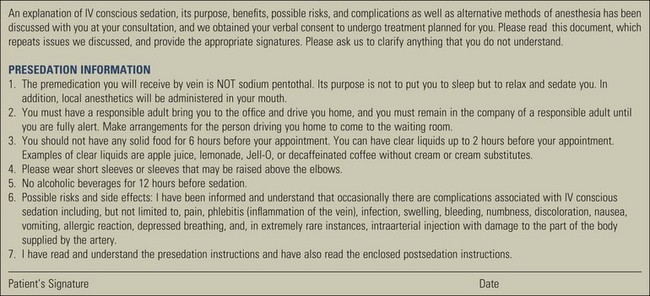

The patient (parent, guardian, or caregiver, if patient is a minor) must be informed about the planned procedure under sedation, including benefits, risks, and instructions for sedation (Figure 55-4). An informed consent for the proposed procedure and sedation must be obtained.

Preoperative dietary restrictions must be considered based on the sedative technique prescribed (Boxes 55-2 and 55-3; see also Figure 55-4).

BOX 55-2 From Merin RL: J Calif Dent Assoc 34:959–968, 2006. Mild Sedation: Suggested Protocol for the Use of Adult Oral Sedative Premedication for Anxious or Fearful Dental Patients

BOX 55-3 From Merin RL: J Calif Dent Assoc 34:959–968, 2006. Mild Sedation: Example of Suggested Patient Pretreatment Instructions

Personnel and Equipment

Personnel

At least one additional person trained in Basic Life Support (BSL) for Healthcare Providers must be present in addition to the dentist.

Equipment

Determination of adequate oxygen supply and equipment necessary to deliver oxygen under positive pressure must be completed. A positive-pressure oxygen delivery system suitable for the patient being treated must be immediately available. An appropriate scavenging system must be available if gases other than oxygen or air are used.

When inhalation equipment is used, it must have a fail-safe system that is appropriately checked and calibrated. The equipment must also have either (1) a functioning device that prohibits the delivery of less than 30% oxygen or (2) an appropriately calibrated and functioning in-line oxygen analyzer with audible alarm.

For moderate sedation, the equipment necessary to establish IV access must be available. This includes a catheter or butterfly needle, an IV drip line, a solution bag (saline or dextrose), tourniquet, and appropriate antiseptic/dermal disinfectant (Figure 55-5).

Figure 55-5 Equipment and supplies needed for the administration of moderate intravenous (IV) sedation includes catheter or butterfly needle (A), an IV drip line (B), a solution bag–saline or dextrose (C), tourniquet (D), and appropriate antiseptic/dermal disinfectant (E).

(From Malamed SF: Sedation: a guide to patient management, ed 5, St. Louis, 2010, Elsevier.)

Monitoring and Documentation

Monitoring

The dentist or an appropriately trained individual, directed by the dentist, must remain in the operatory during active dental treatment with sedation to monitor the patient continuously until he/she meets the criteria for discharge (Box 55-4). The appropriately trained individual must be familiar with monitoring techniques and equipment.

In the case of moderate sedation, a qualified dentist administering moderate sedation must remain in the operatory room to monitor the patient continuously until the patient meets the criteria for recovery. When active treatment concludes and the patient recovers to a minimally sedated level, a qualified auxiliary may be directed by the dentist to remain with the patient and continue to monitor him or her as explained in the guidelines until discharged from the facility. The dentist must not leave the facility until the patient meets the criteria for discharge and is discharged to go home with a responsible adult (see Box 55-4).

Monitoring equipment must include a sphygmomanometer, positive pressure oxygen delivery system, suction, and if inhalation sedation is used, a fail-safe and scavenging system. In the case of moderate sedation, a pulse oximeter, equipment for IV access, and reversal agents for drugs used must also be available (Table 55-3).

TABLE 55-3 Equipment Required For Mild or Moderate Sedation

| Mild or Moderate Sedation | Moderate Sedation |

|---|---|

In the case of moderate sedation, the level of consciousness (e.g., responsiveness to verbal command) must be continually assessed (Table 55-4).

TABLE 55-4 The Observers Assessment of Alertness/Sedation Scale

| Category | Observation | Score |

|---|---|---|

| Responsiveness | Responds readily to name spoken in normal tone. | 5 |

| Lethargic response to name spoken in normal tone. | 4 | |

| Responds only after name is called loudly and/or repeatedly. | 3 | |

| Responds only after mild prodding or shaking. | 2 | |

| Does not respond to mild prodding or shaking. | 1 | |

| Speech | Normal. | 5 |

| Mild slowing or thickening. | 4 | |

| Slurring or prominent slowing. | 3 | |

| Few recognizable words. | 2 | |

| Facial expression | Normal. | 5 |

| Mild relaxation. | 4 | |

| Marked relaxation (slack jaw) | 3 | |

| Eyes | Clear, no ptosis. | 5 |

| Glazed or mild ptosis (less than half of the eye). | 4 | |

| Glazed and marked ptosis (half of the eye or more). | 3 |

Adapted from Chernik DA, Gillings D, Laine H, et al: J Clin Psychopharmacol 10:244–251, 1990.

The color of the mucosa, skin, or blood must be evaluated continuously to assess oxygenation. Oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry is clinically useful and should be considered for minimal sedation. For moderate sedation, oxygen saturation must be continuously evaluated by pulse oximetry. Approximately 98% to 99% of the total oxygen content in arterial blood is bound to hemoglobin within red blood cells. The pulse oximeter measures the degree hemoglobin is saturated with oxygen (SpO2). The remaining 1% to 2% of oxygen is dissolved in plasma and produces a gas pressure referred to as arterial oxygen tension (PaO2). The PaO2 level is what determines how much oxygen is entering the body tissues and is referred to as oxygenation. Normally, the SpO2 level is at 98% to 99% and sustains a PaO2 level of about 95%. Normal oxygenation is defined as a PaO2 of 80 to 100 mm Hg. There is a nonlinear relationship between the SpO2 and the PaO2. SpO2 readings of 95% and higher maintain PaO2 at or above 80 mm Hg and prevent hypoxemia (Table 55-5).

TABLE 55-5 Pulse Oximeter Reading and PaO2 Tissue Oxygenation

| Oximeter SpO2 | Arterial Pressure PaO2 | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 95%–99% | 80–100 mm Hg | Normal oxygenation |

| 90% | 60 mm Hg | Alarm goes off; patient hypoxemia |

| 80% | 45–50 mm Hg | Severe hypoxemia |

The dentist and/or appropriately trained individual must monitor respirations continually. This can be accomplished by auscultation of breath sounds with a precordial stethoscope, monitoring end-tidal carbon dioxide (CO2) or by verbal communication with the patient.

Blood pressure and heart rate should be evaluated preoperatively, postoperatively, and intraoperatively as necessary in cases of minimal sedation. For moderate sedation, the dentist must continually evaluate blood pressure and heart rate. Continuous electrocardiograph (ECG) monitoring of patients with significant cardiovascular disease should be considered.

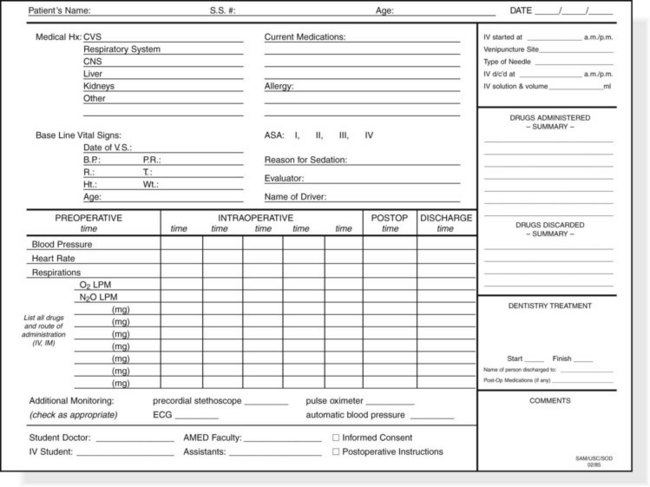

Documentation

An appropriate, time-oriented anesthetic record must be maintained with the names and dosages of all drugs administered (including local anesthetics) and monitored physiologic parameters, including blood pressure, pulse, and respiratory rate (Figure 55-6). In cases of moderate sedation, oxygen saturation must be monitored and recorded continuously (e.g., pulse oximetry).

Recovery and Discharge

Oxygen and suction equipment must be immediately available in the treatment room and the recovery room (if a separate recovery area is utilized). The qualified dentist or appropriately trained clinical staff must continually monitor the patients blood pressure, heart rate, and respirations. In cases of moderate sedation, oxygen saturation and level of consciousness must be evaluated continuously. The qualified dentist must determine and document that the level of consciousness, oxygenation, ventilation, and circulation are satisfactory before discharge (see Box 55-4).

Postoperative verbal and written instruction must be given to the patient and a responsible adult (e.g., parent, escort, guardian, or caregiver).

If a reversal agent is administered before discharge criteria have been met, the patient must be monitored until recovery is assured. A potential problem when using reversal agents is the possibility that the duration of action of the reversal agent may be shorter than the sedative agent used, and the patient may become sedated again. It is critical for the clinician to understand and appreciate the duration of action of all sedative and reversal agents used.

Mild Sedation/Anxiolysis

Oral sedation can help reduce anesthetic failures and decrease anxiety in a large percentage of dental patients.19,47 Oral premedication is cost-effective and requires minimal monitoring when correct doses are used.13,14 Most states do not require special permits for dentists who are prescribing sedatives to achieve mild sedation/anxiolysis. State laws do vary, and dentists need to check with their own dental board. Mild sedation dosages are generally defined as less than or equal to the single maximum recommended dose that can be prescribed for home use. Generally, these maximum doses can be found in references such as the package inserts, pharmaceutical websites, articles in the dental literature, and yearly updated books such as the Physicians’ Desk Reference.

The use of oral sedation premedication is both an art and a science. It is wise for dentists to become very familiar with a small number of oral sedative regimens. In this way, one has a better chance of accurately predicting the correct dose for each patient and understanding the precautions and side effects of each agent. Although there are a large number of oral sedative agents available by prescription, recent dental articles have concentrated on the use of zaleplon, triazolam, and lorazepam.* As an example, diazepam has been recommended for dental anxiety in several references.11,33,60 Its duration of action is 6 to 8 hours. However, it has a primary half-life of 20 to 80 hours and a 40- to 120-hour half-life for active secondary metabolites. In addition, two head-to-head comparisons of diazepam and triazolam found triazolam to be a more effective anxiolytic agent.17,46 The remainder of this section discusses guidelines and protocols for the use of these three oral sedative agents.

Zaleplon is a short-acting hypnotic in the pyrazolopyrimidine class. The onset of action of zaleplon is usually within 30 minutes, and it is rapidly eliminated with a half-life of approximately 1 hour. Zaleplon is a relatively new agent, and there are relatively few articles on its use in dentistry. Both triazolam and lorazepam are benzodiazepine medications, and the main difference is the effective time of sedation. The duration of action of triazolam is 2 to 4 hours compared to 4 to 8 hours for lorazepam (Table 55-6). It is important for the dentist to carefully review the patient’s past medical history to rule out any contraindications to these medications before the treatment appointment.

Suggested patient pretreatment instructions are presented in Box 55-3. Patients must understand that they will need a responsible adult to escort them home when they take a sedative medication. Patients who are not reliable at following directions are not good candidates for oral sedative premedication.

Guidelines for Mild Sedation with Oral Medications

This section provides guidelines for the mild sedation/anxiolytic doses for these medications, but these recommendations should not be a substitute for good clinical judgment and direct patient assessment. Patient factors, such as diminished liver enzyme function, extremes of age, and drug tolerance as the result of past drug use may cause alterations in the proposed protocol. Precautions and drug interactions for zaleplon, triazolam, and lorazepam are presented in Boxes 55-5, 55-6, and 55-7, respectively. If the calculated amount of medication is ineffective, the dentist can choose to terminate the dental appointment or continue if the patient is willing. If the patient’s anxiety is not sufficiently diminished, the dentist must follow all normal dismissal procedures, including releasing the patient to a responsible adult because the sedative agent may impair motor activity even when not relieving dental anxiety. A failure to produce anxiolysis may require changing future prescriptions, using the services of a dental anesthesiologist in your office, or referring the patient to an office that provides conscious sedation or general anesthesia.

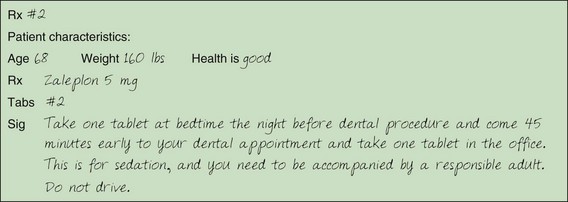

Figure 55-7 Sample zaleplon prescription.

(Modified from Merin RL: J Calif Dent Assoc 34:959–968, 2006.)

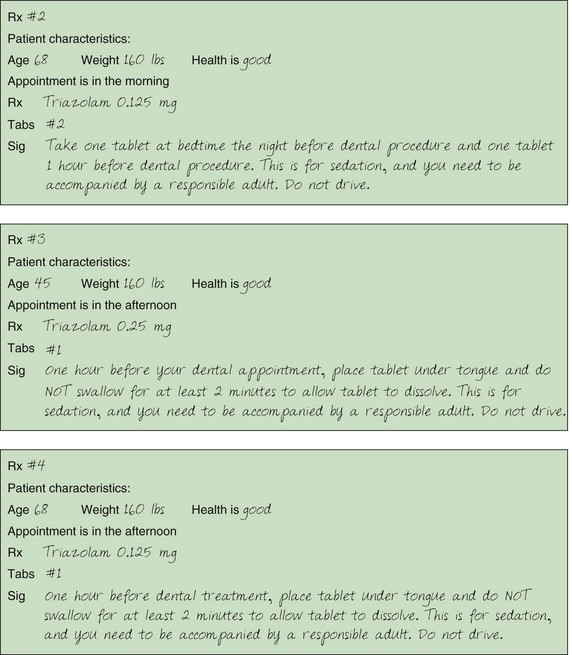

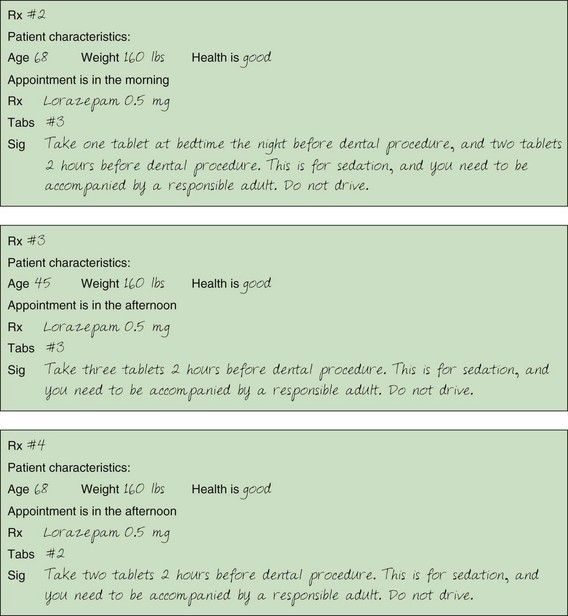

Anxiolytic dosing guidelines for zaleplon, triazolam, and lorazepam are presented in Table 55-7. A recent review of the dental literature suggests a maximum dose of 0.625 mg of triazolam or 2.5 mg of lorazepam for anxiolysis.27 However, it is important to recognize that individual tolerance and responses vary and that maximum and average doses are not appropriate for all patients. It is necessary to adjust dosages according to weight, age, health status, and other prescribed medications, as well as previous patient experiences with sedative agents. The literature shows that age-related changes can impair benzodiazepine metabolism, and the maximum anxiolytic dose for elderly patients should be reduced by 50% for triazolam and 30% to 50% for lorazepam.28 The opposite is true for younger adult patients (under 40 years) who may need a 25% increase in their weight-related anxiolytic dose. Sample prescriptions for zaleplon, triazolam, and lorazepam are presented in Figures 55-7, 55-8, and 55-9, respectively.

Figure 55-8 Sample triazolam prescription.

(Modified from Merin RL: J Calif Dent Assoc 34:959–968, 2006.)

Figure 55-9 Sample lorazepam prescriptions.

(Modified from Merin RL: J Calif Dent Assoc 34:959–968, 2006.)

BOX 55-5 CNS, Central nervous system.

Zaleplon Precautions and Drug Interactions*

Relative and Absolute Contraindications

Pregnancy, liver impairment, severe renal disease, respiratory disease, mental depression, children.

Drug Interactions that May Increase Effects

Imipramine, thioridazine, cimetidine, erythromycin, ketoconazole, other CNS depressants

Drug Interactions that May Decrease Effect

Hepatic cytochrome P450 enzyme inducers such as carbamazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, rifampin

Foods that May Decrease Effect

St John’s wort, caffeine. A high-fat/heavy meal can reduce the peak blood levels by 35% and the time to peak plasma levels by 2 hours.

* Note this is a relatively new drug and there are many potential drug interactions that have not been studied.

BOX 55-6 Triazolam Precautions and Drug Interactions

Relative and Absolute Contraindications

Acute narrow angle glaucoma; uncorrected open angle glaucoma; myasthenia gravis; respiratory diseases, including severe sleep apnea and severe COPD; pregnancy; lactation; severe liver impairment; renal impairment; children; mental depression; hypersensitivity to this drug or other benzodiazepines.

Drug Interactions that May Increase Effect

Other CNS depressants, isoniazid, oral contraceptives, ranitidine, CYP3A4 inhibitors such as macrolide antibiotics (erythromycin, clarithromycin), azole antifungals, doxycycline, some calcium channel blockers.

Drug Interactions that May Decrease Effect

Theophylline, CYP3A4 inducers such as aminoglutethimide, carbamazepine, nafcillin, nevirapine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, and rifamycins.

BOX 55-7 Lorazepam Precautions and Drug Interactions

Relative and Absolute Contraindications

Acute narrow angle glaucoma; uncorrected open angle glaucoma; myasthenia gravis; respiratory diseases, including severe sleep apnea and severe COPD; pregnancy; lactation; severe liver impairment; renal impairment; children; mental depression, hypersensitivity to this drug or other benzodiazepines.

Drug Interactions that May Increase Effect

Other CNS depressants, probenecid (used for gout). Drugs that inhibit the oxidative metabolism of triazolam are less likely to affect lorazepam, which undergoes direct glucuronide conjugation.

When using a very short-acting agent, such as zaleplon, there is a risk that recovery of psychomotor functions may take longer than 1 hour after the onset of action despite the reported duration of action. Also, when using triazolam with anxiolytic doses (generally higher than the hypnotic dose), there is a risk that full recovery to a normal state of consciousness may take longer than 4 hours. Ganzberg found that 28.5% of the zaleplon-sedated patients and 78.5% of the triazolam-sedated patients felt that the sedation effects lingered for the rest of the day.26 Consequently, zaleplon and triazolam patients must be accompanied by a responsible adult and not resume normal activities for the remainder of the day. The opposite problem can occur when using short-acting sedative agents. Namely, the sedation effects of the short-acting agent may wear off quickly. For this reason, the dentist must prevent delays or interruptions so that treatment can be completed in a timely manner. If procedures are expected to be longer than 2 hours, it may be best to use a longer acting agent such as lorazepam.

Inhalation Sedation

This section is a general description of the N2O technique. To be competent in N2O sedation, the ADA recommends a minimum course of 14 hours, including a clinical component.3

In 1844, Dr. Horace Wells (Hartford, CT) was the first to recognize and introduce the use of N2O as an analgesic, sedative agent to perform dental surgical procedures. Since that time, N2O has been used with a long safety record in numerous dental procedures. Advantages of N2O are a rapid onset of action and rapid recovery. There are few contraindications (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, severe emotional disturbances, and early pregnancy). Obstacles to the use of N2O include the initial cost of equipment, the need for effective scavenging equipment, periodic maintenance, and the concern that long-term exposure to trace amounts of N2O can be hazardous to dental personnel.

The N2O/O2 inhalation sedation is divided into three phases.41 The technique begins with an induction phase, which leads to a treatment phase and ends with a recovery phase. Each of these phases is described in the following:

Moderate (Conscious) Sedation

The ADA recognizes that moderate sedation requires more training and knowledge than minimal sedation and recommends that moderate sedation providers have current certification in Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) and/or appropriate training in a dental sedation/anesthesia emergency management course.4 Guidelines for course content and adult case experiences recommended for teaching moderate sedation are summarized in Box 55-8.

BOX 55-8 Data from ADA Guidelines for teaching pain control and sedation to dentists and dental students, 2007, www.ada.org. Current policies adopted 1954-2008 © 2009.

ADA Guidelines for Teaching Moderate Enteral and Moderate Parental Sedation 2007

Moderate Enteral Sedation Course

Before performing any moderate sedation technique, practitioners must satisfy all state laws and regulations for the provision of this service. The following discussion is meant to be an overview of some of the popular moderate sedation techniques used to treat periodontal and implant patients. Practitioners must follow the clinical and educational guidelines previously presented in this chapter.

Oral Sedation

Oral Medication with Supplemental Dosing

Most medications available for moderate enteral sedation are used in an “off-label” manner and have no determined MRD for that purpose.16 The most frequently reported agent used is triazolam. A typical regimen would include a dose of triazolam 1 hour before a dental appointment followed by an incremental dose to achieve an adequate level of sedation.16 Since it takes 30 to 90 minutes to reach maximum serum levels, dentists cannot accurately titrate sedation levels with oral and sublingual administration. Donaldson and Goodchild have calculated 24-hour maximum cumulative doses (MCD) for triazolam as 2.0 mg for a young healthy 200-pound patient.16 This dosage needs to be adjusted for patients by weight and health. For healthy, ASA I patients, their weight is divided by 100 to calculate the MCD of triazolam.

In a study on the effects of multidose sublingual triazolam in 10 healthy volunteers, subjects were given 0.25 mg followed by additional doses after 60 minutes (0.5 mg) and 90 minutes (0.25 mg) for a total dose of 1.0 mg. Plasma concentrations of triazolam, sedation scores, and bispectral index scores were greatest at the end of the 3-hour observation period.32 Although all subjects were able to maintain a patent airway independently, eight of the subjects had Observers Assessment of Alertness/Sedation scores (see Table 55-4) consistent with the definition of deep sedation or general anesthesia. Incremental dosing of this short-acting benzodiazepine results in long-lasting sedation, which is dose dependent. In addition, the sedation produced by supplemental dosing of triazolam cannot be reversed by a single submucosal injection of the reversal agent, flumazenil.30 Supplemental doses should only follow an observation period sufficient to assess the drug effects, and the decision to administer additional doses of oral sedatives should be based on direct patient observation.

Combined Oral and Inhalation Sedation

Combining oral benzodiazepines with N2O/O2 inhalation has been shown in both human and animal studies to produce safe and effective sedation.29,31,35,56 The technique is to prescribe a minimal sedation dose of an appropriate benzodiazepine and then titrate N2O/O2 to the appropriate level of moderate sedation. The majority of the published studies used triazolam as the sedative agent. Again, it is important to remember that N2O/O2, when used in combination with sedative agents, may produce sedation that is minimal, moderate, or deep and in some cases may produce general anesthesia. Patients should be monitored carefully to avoid going beyond the intended level of sedation.

Intravenous Sedation

The desired end-point of IV sedation is drowsiness, tranquility, and loss of anxiety. The classical sign of drooping of the eyelid may represent unnecessarily deep sedation.52 The correct level of sedation has been achieved when the patient rests with his or her eyes closed, responds to verbal commands or mild physical stimulation, and shows signs of relaxation.

Single Benzodiazepine Intravenous Sedation Techniques

An initial test dose of 0.2 mg is given and then midazolam is titrated at a rate of 0.5mg per minute until the desired level of sedation is achieved.15,54 The effective loading dose (ELD) is defined as the dose required to reach the level of moderate sedation. Additional IV midazolam can be administered as needed during surgical procedures up to a maximum dose of 10 mg (Table 55-8).

TABLE 55-8 Intravenous Midazolam and Diazepam

| Midazolam | Diazepam | |

|---|---|---|

| Average dose: Periodontal patients56 | 3.3 mg | 12.1 mg |

| Average dose: Dental patients42 | 2.5-7.5 mg | 10 mg |

| Maximum dose | 10 mg | 20 mg |

| Duration of action | 20–45 minutes | 30–60 minutes |

| Half-life | 1.7–2.4 hrs | 31.3 hrs |

| Active metabolites | No | Yes |

| Anterograde amnesia | Good | Fair |

| Ease of titration | Good | Very good |

| Recovery | Abrupt | Slow/smoother |

| Phlebitis potential | Minimal/water soluble | High/not water soluble |

An initial test dose of 1.0 mg is given to determine if there is any unusual drug sensitivity, and then diazepam is titrated at a rate of 2.5 mg per minute until the desired level of sedation is achieved.54 Additional IV diazepam can be administered as needed during the surgical procedures up to a maximum of 20 mg (see Table 55-8).

Combination Intravenous Sedation

When little clinical effect is produced with the usual maximum safe doses of a single sedative agent, further administration of the same drug is unlikely to provide acceptable sedation until extremely large doses are given.57,59 To help prevent sedation failures, combination techniques are required. Administration of two or more sedative agents increases the likelihood of drug synergism and reduces the dose required to render 50% of the patients unconscious (ED-50). When using combination techniques, the clinician must carefully monitor the patient for increased depth of sedation beyond that which is desired, and be prepared to stop the periodontal procedure until the patient is returned to the appropriate level of sedation. Opioids are frequently combined with benzodiazepines to produce analgesia, drowsiness, changes in mood, and mental clouding. All opioids produce dose-related respiratory depression, which is a major factor in morbidity and mortality related to IV sedation.

Meperidine Combined with Diazepam or Midazolam

The benzodiazepine is titrated in the usual manner until the desired (minimal to moderate) sedation is produced. A small test dose of meperidine is given initially to see if there is any unusual reaction. Meperidine is titrated at a rate of 5 mg per minute until moderate sedation is produced (up to a maximum dose of 50 mg). The dose can be estimated on the basis of the effective loading dose of the benzodiazepine given. The clinical effects of meperidine are exhibited 2 to 4 minutes after IV administration, which may lead to excessive sedation if administered too rapidly.41 For this reason, all narcotics should be administered slowly when the goal is moderate sedation in order to avoid deep sedation or general anesthesia. The rate of administration determines the initial depth of anesthesia.

Fentanyl Combined with Midazolam

Fentanyl is a rapid-onset, short-acting opioid agonist. After IV administration the onset of analgesia and sedation occurs within less than a minute, although the maximal analgesic and respiratory depressant effects do not develop for several minutes. The respiratory depressant effects of fentanyl last longer than its analgesic and sedative properties, and this can be a problem for patients dismissed from the office.41 Fentanyl techniques usually recommend that the fentanyl be administered prior to the midazolam.15,52 Fentanyl is administered first in a fixed dose of .001 mg/kg via slow IV infusion over 2 minutes. The time between injection and clinical effect is the lead-time for that patient. Later in the procedure, knowledge of the lead-time is useful in timing the administration of subsequent doses. Midazolam is then administered at a rate of 0.5 mg per minute until the appropriate level of sedation is produced.

Combined Oral and Intravenous Sedation

In reviewing the dental literature, there were five reports of combining oral and IV sedation or general anesthesia in dental patients.39,43,44,55 All of these studies found that oral sedation reduced the pre-operative anxiety and improved overall patient comfort.

Patients are prescribed a minimal sedation dose of lorazepam (described in this chapter) to be taken at home. As the patient walks into the operatory, they are assessed as to how sedated they are from the oral lorazepam, which is interpreted as their sensitivity to benzodiazepines. Vital signs are measured, and an IV drip is started. Midazolam is titrated to the level of moderate sedation. The amount of IV midazolam required is generally small (1 to 2 mg) because the patient is already sedate from the oral lorazepam. Midazolam generally produces good amnesia, but at times the patient can be talkative and not feel sleepy. At this time small amounts of IV pentobarbital (12.5 to 50 mg) can be titrated to provide the patient with a feeling of more profound sedation.

Rationale for Technique

One author (RM) has been using the combined oral and IV sedation technique for more than ten years, and has found it to be very effective. Lorazepam was selected for oral premedication for several reasons. The duration of action is appropriate for periodontal procedures, and several studies have shown that it works well to relieve anxiety before surgical procedures.12,24,25,48 When anxious patients are sedated without oral premedication, they usually cannot be slowly titrated. They need to be given a slightly larger dose and put into a deeper level of sedation temporarily to overcome their initial anxiety. With effective oral premedication, they can be slowly titrated to the desired level of sedation. Although midazolam produces good amnesia, it has been this author’s and other authors’ experience that midazolam is sometimes difficult to smoothly titrate to a light sedation level.54 This is sometimes referred to as “reading the patient.” After administering IV midazolam, many patients will be talkative and say “I don’t feel sedated,” even though the dentist knows they are already affected by the midazolam and will probably not remember what they are saying. By adding a small amount of sodium pentobarbital, the patients will state that they feel the affects of sedation and are slightly sleepy. Only small amounts of pentobarbital are required since barbiturates increase the affinity of benzodiazepine receptors to midazolam and are supra additive in producing increased sedation.36 Although pentobarbital has no reversal agent, it has been used safely for many years as a sedative in dentistry.41