Chapter 10 Palliative medicine and symptom control

Introduction and general aspects

Palliative care is the active total care of patients who have advanced, progressive life-shortening disease. It is now recognized that palliative care should be based on needs not diagnosis: it is needed in many non-malignant diseases as well as in cancer (Box 10.1).

![]() Box 10.1

Box 10.1

Key components of a modern palliative care service

Management should be based on needs not diagnosis: the symptom burden of non-malignant disease often equals that of cancer

Management should be based on needs not diagnosis: the symptom burden of non-malignant disease often equals that of cancer

Care should be independent of the patients’ location and should help patients to remain at home if possible, avoiding unwanted admissions to hospital

Care should be independent of the patients’ location and should help patients to remain at home if possible, avoiding unwanted admissions to hospital

Rehabilitation for people with advanced disease

Rehabilitation for people with advanced disease

Bereavement care for people with pathological grief problems

Bereavement care for people with pathological grief problems

Telephone advice for other clinicians; disseminating palliative care knowledge

Telephone advice for other clinicians; disseminating palliative care knowledge

Teaching for clinicians, from undergraduate level to postgraduate life-long learning

Teaching for clinicians, from undergraduate level to postgraduate life-long learning

The goal of palliative care is to achieve the best possible quality of life for patients and their carers by managing not only physical symptoms, but also psychological, social and spiritual problems. When life-prolonging treatments are no longer improving or maintaining quality of life, death is accepted as a normal process. The aim is to enable the patient to be cared for and to die in the place of their choice, with excellent symptom control and an opportunity to say goodbye and bring closure.

Who provides palliative care?

A hallmark of palliative care is the multiprofessional team, as single professionals cannot provide the breadth of necessary expertise, and the emotional demands of working in this area require team support to enable balanced, compassionate but dispassionate care.

All healthcare providers should have basic palliative care skills and access to a specialist palliative care (SPC) team. They should be aware of the services that the local SPC teams can offer and recognize when referral is appropriate. A problem-based approach to disease management will ensure that patients and carers obtain access to appropriate support services, including SPC and will avoid an either/or approach (‘either curative treatment or palliative care’).

Good communication between members of the healthcare team, and the patient and carer underpins the successful management of advanced disease and end-of-life care. Good liaison between the hospital, primary care and hospice is also essential.

Importance of early assessment

Early assessment of needs, with SPC referral if required, is crucial to obtaining the best outcome for rehabilitation and for maintaining or improving quality of life for both patient and carer. Palliative care is most effective when it is given as soon as possible after diagnosis and is given alongside disease-specific therapy, such as radio/chemotherapy for cancer or cardiac medication for heart failure. Early referral links palliative care with quality of life improvements; positive associations increase the likelihood that patients and families continue to use palliative care services when they need them. Furthermore, in malignant disease, there is good evidence that integrating palliative care and anti-tumour treatment soon after diagnosis reduces long-term distress and increases survival in selected cases.

If palliative care is seen only as relevant for the end-of-life phase, patients who have non-malignant disease are denied expert help for complex symptoms. Timely management of physical and psychosocial issues earlier in the course of disease prevents intractable problems later (Box 10.2).

![]() Box 10.2

Box 10.2

Problems arising when specialist palliative care (SPC) is delayed until the end-of-life

There is insufficient time to achieve good symptom control by combining non-pharmacological and pharmacological components

There is insufficient time to achieve good symptom control by combining non-pharmacological and pharmacological components

SPC services are deemed less acceptable by patient and family, being associated with ‘dying’ or ‘giving up’ or ‘giving in’ to illness

SPC services are deemed less acceptable by patient and family, being associated with ‘dying’ or ‘giving up’ or ‘giving in’ to illness

Psychological distress and physical symptoms become intractable and contribute to complex grief

Psychological distress and physical symptoms become intractable and contribute to complex grief

It becomes too late to adopt rehabilitative approach or teach/use non-pharmacological interventions that need a degree of training and patient motivation (e.g. cognitive behavioural approaches, mindfulness meditation, attendance at day therapy)

It becomes too late to adopt rehabilitative approach or teach/use non-pharmacological interventions that need a degree of training and patient motivation (e.g. cognitive behavioural approaches, mindfulness meditation, attendance at day therapy)

Assessment of patient’s needs and understanding

The causes of a patient’s symptoms are often multifactorial, and a holistic assessment is central to optimum management. Assessment of the patient’s understanding of the disease, understanding their future wishes and acknowledging their concerns, will help the team plan and implement effective support. Patients will have differing needs for information, and will deal with ‘bad news’ in different ways. A sensitive approach, respecting individual requirements, is crucial.

Recent changes in provision of palliative care

An increase in the number of patients who survive malignant disease and a recognition of the needs of patients who have non-malignant disease have led to changes in the provision of SPC services. Many patients will use SPC services for a limited period (weeks to months) whilst complex problems are addressed, and then are discharged with the opportunity for re-referral if help is required later.

Symptom control

This section outlines the medical aspects of symptom control. Good palliative care integrates these with appropriate non-pharmacological approaches, including anxiety management and rehabilitation (see p. 489).

Pain

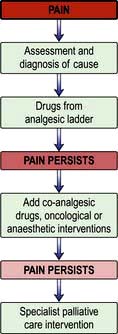

Pain is a feared symptom in cancer and at least two-thirds of people with cancer suffer significant pain. Pain has a number of causes, and not all pains respond equally well to opioid analgesics (Fig. 10.1). The pain is either related directly to the tumour (e.g. pressure on a nerve) or indirectly, for example due to weight loss or pressure sores. It may result from a co-morbidity such as arthritis. Emotional and spiritual distress may be expressed as physical pain (termed ‘opioid irrelevant pain’) or will exacerbate physical pain.

The term ‘total pain’ encompasses a variety of influences that contribute to pain:

Biological: the cancer itself, cancer therapy (drugs, surgery, radiotherapy)

Biological: the cancer itself, cancer therapy (drugs, surgery, radiotherapy)

Social: family distress, loss of independence, financial problems from job loss

Social: family distress, loss of independence, financial problems from job loss

Psychological: fear of dying, pain, or being in hospital; anger at dying or at the process of diagnosis and delays; depression from all of above

Psychological: fear of dying, pain, or being in hospital; anger at dying or at the process of diagnosis and delays; depression from all of above

Spiritual: fear of death, questions about life’s meaning, guilt.

Spiritual: fear of death, questions about life’s meaning, guilt.

FURTHER READING

SIGN. Control of Pain in Adults with Cancer. Publication No. 106. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2008; http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/SIGN106.pdf.

The WHO analgesic ladder

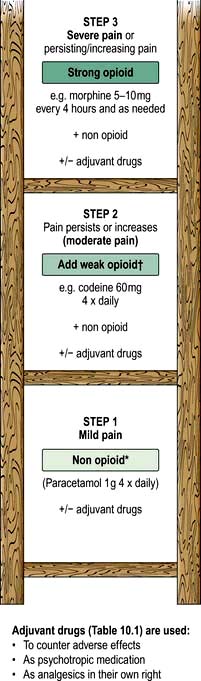

Most cancer pain can be managed with oral or commonly used transdermal preparations. The World Health Organization (WHO) cancer pain relief ladder guides the choice of analgesic according to pain severity (Fig. 10.2, Table 10.1).

Figure 10.2 WHO analgesic ladder for cancer and other chronic pain. Step 2 can be omitted, going to morphine immediately. Adjuvant drugs are listed in Table 10.1. *Opioids include all drugs with an action similar to morphine, i.e. binding to endogenous opioid receptors. †Continue NSAID/paracetamol regularly when opioid started.

Table 10.1 Commonly used adjuvant analgesics

| Drugs | Indication |

|---|---|

NSAIDs, e.g. diclofenac |

Bone pain, inflammatory pain |

Anticonvulsants, e.g. gabapentin (600–2400 mg daily) or pregabalin (150 mg at start increasing up to 600 mg daily) |

Neuropathic pain |

Tricyclic antidepressants, e.g. amitriptyline (10–75 mg daily) |

Neuropathic pain |

Bisphosphonates, e.g. disodium pamidronate |

Metastatic bone disease |

Dexamethasone |

Neuropathic pain, inflammatory pain (e.g. liver capsule pain), headache from cerebral oedema due to brain tumour |

If regular use of optimum dosing (e.g. paracetamol 1 g × 4 daily for step 1) does not control the pain, then an analgesic from the next step of the ladder is prescribed. As pain is due to different physical aetiologies, an adjuvant analgesic may be needed in addition or instead, such as the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline for neuropathic pain (Table 10.1).

Strong opioid drugs

Dose titration and route

Morphine is the drug of choice and, in most circumstances, should be given regularly by mouth. The dose should be tailored to the individual’s needs by allowing ‘as required’ doses; morphine does not have a ‘ceiling’ effect. If a patient has needed further doses in addition to the regular daily dose, then the amount in the additional doses can be added to the following day’s regular dose until the daily requirement becomes stable; a process called ‘titration’. When the stable daily dose requirement has been established, the morphine can be changed to a sustained-release preparation. For example:

The starting dose of morphine is usually 5–10 mg every 4 hours, depending on patient size, renal function and whether they are already taking a weak opioid.

If there is significant renal dysfunction, morphine should be used in low doses and should not be given in continuous dose regimens (e.g. by subcutaneous infusions) because of the risk of metabolite accumulation (it is renally excreted). In renal impairment, an alternative opioid (e.g. fentanyl) can be given transdermally, e.g. 72-hour self-adhesive patches.

If a patient is unable to take oral medication due to weakness, swallowing difficulties or nausea and vomiting, the opioid should be given parenterally. For cancer patients who are likely to need continuous analgesia, continuous subcutaneous infusion is the preferred route.

Both doctors and patients may have erroneous beliefs (e.g. fear of addiction), which mean that adequate doses of opioids are not prescribed or taken; however, addiction is very rare with the risk of iatrogenic addiction being <0.01%.

Side-effects

The most common side-effects are:

Nausea and vomiting: this can usually be managed or prevented with antiemetics (such as metoclopramide). Some antiemetics can be combined with an opioid, e.g. haloperidol or metoclopramide; always check compatibility data.

Nausea and vomiting: this can usually be managed or prevented with antiemetics (such as metoclopramide). Some antiemetics can be combined with an opioid, e.g. haloperidol or metoclopramide; always check compatibility data.

Constipation is common and should be anticipated with administration of a combination of stool softener (e.g. macrogols) and stimulants either separately or in one preparation Methyl naltrexone is a peripherally acting opioid receptor antagonist which is used if response to other laxatives is poor.

Constipation is common and should be anticipated with administration of a combination of stool softener (e.g. macrogols) and stimulants either separately or in one preparation Methyl naltrexone is a peripherally acting opioid receptor antagonist which is used if response to other laxatives is poor.

If side-effects are intractable, a change of opioid is often helpful.

Toxicity

Confusion, persistent and undue drowsiness, myoclonus, nightmares and hallucinations indicate opioid toxicity. This may follow rapid dose escalation and responds to dose reduction and slower re-titration. It may indicate poorly opioid responsive pain and the need for adjuvant analgesics.

Antipsychotics such as haloperidol may help settle the patient’s distress whilst waiting for resolution of toxicity. Some patients will tolerate an alternative opioid better, e.g. oxycodone, or, an alternative route, e.g. subcutaneous injection.

Adjuvant analgesics

The most commonly used adjuvant analgesics are described in Table 10.1. Other treatments such as radio/chemotherapy, anaesthetic or neurosurgical interventions, acupuncture and TENS may be useful in selected patients.

Regular review is necessary to achieve optimal pain control, including regular assessment to distinguish pain severity from pain distress.

Gastrointestinal symptoms

Anorexia, weight loss, malaise and weakness

These result from the cancer-cachexia syndrome of advanced disease and carry a poor prognosis. Although attention to nutrition is necessary, the syndrome is mediated through chronic stimulation of the acute phase response, and tumour-secreted substances (e.g. lipid mobilizing factor and proteolysis inducing factor). Thus, calorie-protein support alone gives limited benefit: parenteral feeding has been shown to make no difference to patient survival or quality of life.

There is a small and evolving evidence base for specific therapies such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) fish oil, cyclo-oxygenase (COX) inhibition with an NSAID and antioxidant treatment, but currently, unless the patient is fit enough for, and responds to, anti-tumour therapy, management is supportive. Some patients benefit from a trial of a food supplement that contains EPA and antioxidants. Megestrol may help appetite, but weight gain is usually fluid or fat. It is also thrombogenic and is of little benefit.

Until recently, corticosteroids were recommended and they are still commonly used as an appetite stimulant; however, the weight gained is usually fluid and muscle catabolism is accelerated. Also, any benefit in appetite stimulation tends to be short-lived. Thus, their use should be limited to short term only.

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting is common, and often due to use of opioids without antiemetics such as haloperidol 1.5 mg × 1–2 daily or metoclopramide 10–20 mg × 3 daily. When nausea and vomiting are associated with chemotherapy, patients should have an antiemetic, starting with metoclopramide or domperidone, but if the risk of nausea and vomiting is high, give a specific 5HT3 antagonist, e.g. ondansetron 8 mg orally or by slow i.v. injection.

For most chemical causes, e.g. hypercalcaemia, haloperidol 1.5–3 mg daily is the first choice. Metoclopramide is also a prokinetic and therefore useful for emesis due to gastric stasis or constipation. Cyclizine 50 mg × 3 daily is also used.

For any cause of vomiting, it may be necessary to start antiemetic therapy parenterally by continuous subcutaneous infusion to gain control. If the patient has gastrointestinal obstruction, this route may need to be continued.

Gastric distension

Gastric distension due to pressure on the stomach by the tumour (squashed stomach syndrome) is treated with a prokinetic, e.g. domperidone 10 mg × 3 daily.

Bowel obstruction

Metoclopramide should be avoided in complete bowel obstruction where an antispasmodic such as hyoscine butylbromide (60–120 mg/24 hours s.c.) is preferred. Control of vomiting in bowel obstruction may also need the addition of octreotide (a somatostatin analogue) to reduce gut secretions and volume of vomitus, or physical measures such as defunctioning colostomy or a venting gastrostomy. Occasionally, a lower bowel obstruction is resolved with insertion of a stent, or transrectal resection of tumour. Steroids shorten the length of episodes of obstruction, if resolution is possible.

In advanced disease, the patient should be encouraged to drink and take small amounts of soft diet as they wish. With good mouth care, the sensation of thirst is often avoidable, thus sometimes preventing the need for parenteral fluids.

Respiratory symptoms

Breathlessness

Breathlessness remains one of the most distressing and common symptoms in palliative care; causing the patient serious discomfort, it is highly distressing for carers to witness. Full assessment and active treatment of all reversible conditions, such as drainage of pleural effusions, or optimization of treatment of heart failure or chronic pulmonary disease is mandatory. In advanced cancer, breathlessness is often multifactorial in origin and many of the contributory factors are irreversible (e.g. cachexia), so a ‘complex intervention’ combining a number of different treatment strategies has the greatest impact. Aspects of breathlessness management are summarized in Box 10.3.

![]() Box 10.3

Box 10.3

Key points for successful management of breathlessness

Start treatment early: patients who are likely to develop breathlessness should learn non-pharmacological approaches early in the disease course, before breathlessness has become severe.

Start treatment early: patients who are likely to develop breathlessness should learn non-pharmacological approaches early in the disease course, before breathlessness has become severe.

Involve the carer in the treatment strategy: watching breathlessness episodes and being unable to help is a terrifying experience (and promotes the panic–anxiety cycle); if patients and carers develop a joint ritual for crises, chronic anxiety can be reduced.

Involve the carer in the treatment strategy: watching breathlessness episodes and being unable to help is a terrifying experience (and promotes the panic–anxiety cycle); if patients and carers develop a joint ritual for crises, chronic anxiety can be reduced.

Ensure management is rehabilitative (see p. 489): this increases physical fitness, hope, self-efficacy, and may enable patient and carer to achieve goals that once seemed impossible.

Ensure management is rehabilitative (see p. 489): this increases physical fitness, hope, self-efficacy, and may enable patient and carer to achieve goals that once seemed impossible.

Integrate psychological, physical and social interventions, as with all palliative care.

Integrate psychological, physical and social interventions, as with all palliative care.

Breathlessness with panic and anxiety

Patients often experience a panic–breathlessness cycle and fear dying during an acute episode of breathlessness. This is extremely unlikely in chronic disease, unless there is an acute complication, and reassurance will help. The perception of breathlessness is mediated by the central nervous system and can be modulated by thoughts and feelings about the sensation. Education about breathlessness and exploration of psychological precipitators or maintainers can reduce its impact.

Using a hand-held fan to alleviate breathlessness. For more on interventions for breathlessness, see http://www.cuh.org.uk/breathlessness.

Non-pharmacological approaches such as using a hand-held fan, pacing, prioritizing activities to avoid over-exertion, breathing training and anxiety management are helpful (Table 10.2). There is no evidence to suggest that oxygen therapy reduces the sensation of breathlessness in advanced disease and the hand-held fan should be used before oxygen for this purpose. Opioids, used orally or parenterally, can palliate breathlessness. If panic/anxiety is significant, a quick-acting benzodiazepine such as lorazepam (used sublingually for rapid absorption) may be useful.

Table 10.2 Key non-pharmacological interventions for breathlessness

| Intervention | Putative mechanism of action | Most useful |

|---|---|---|

Hand-held fan |

Cooling area served by 2nd and 3rd branches of trigeminal nerve |

Reducing length of episodes of SOB on exertion or at rest |

Reduces temperature of air flowing over nasal receptors, altering signal to brainstem respiratory complex and so changing respiratory pattern |

Gives patient and carer confidence to have an intervention they can use |

|

Exercise |

Stops spiral of disability developing |

Patients who are still quite mobile. |

Changes muscle structure: less lactic acid produced |

In patients who have not developed onset of SOB, reduce/defer symptoms by reducing deconditioning |

|

Anxiety reduction, e.g. CBT (needs skilled clinician to administer) or simple relaxation therapy |

Works on central perception of breathlessness reducing impact |

People with higher levels of anxiety at baseline (i.e. when first seen) |

Interrupting panic/anxiety cycle |

Patients willing to persevere with learning a new skill |

|

Carer support |

Reduces carer anxiety and distress which is part of ‘total’ anxiety–panic cycle |

Where carer is isolated, under extra pressures (e.g. looking after elderly parent, going through divorce) |

Breathing retraining |

Improve mechanical effectiveness respiratory system |

Chronic advanced respiratory disease and those with anxiety-related breathlessness |

Pacing (finding a balance between activity and rest to achieve aims) and prioritizing (deciding which daily activities are most necessary and focusing energy use on them) |

Avoids over-exertion which can lead to exhaustion, inactivity and subsequent deconditioning |

Patients who are able and willing to modify daily routines |

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation |

Increases muscle bulk, simulating effect of exercise |

Patients who live alone |

Those unable to get out to attend rehabilitation group |

||

People with a short prognosis |

||

People with co-morbidities that prevent exercise |

CBT, cognitive behavioural therapy; SOB, short of breath (breathlessness).

Cough

Persistent unproductive cough is another troublesome symptom that can be helped by the antitussive effect of opioids (e.g. morphine). Excessive respiratory secretions can be treated with hyoscine hydrobromide 400–600 µg every 4–8 hours but does give a dry mouth. Glycopyrronium is also useful by subcutaneous infusion of 0.6–1.2 mg in 24 hours.

Other physical symptoms

People with cancer may develop other physical symptoms caused directly by the tumour (e.g. hemiplegia due to brain secondaries) or indirectly (e.g. bleeding or venous thromboembolism due to disturbances in coagulation). Symptoms may also result from treatment, such as lymphoedema following treatment for breast or vulval cancer, or heart failure secondary to anthracycline or trastuzumab therapy. The principles of holistic assessment, reversal of reversible factors and appropriate involvement of the multiprofessional team should be applied.

Lymphoedema

The pain and disabling swelling associated with lymphoedema can be alleviated through complete decongestive therapy (CDT), a treatment which is a massage-like technique and comprises manual lymphatic drainage, compression bandaging and gentle exercise. Diuretics should not be used. Referral to a specialist lymphoedema therapist or nurse is useful.

Fatigue

Fatigue is a significant and debilitating problem for palliative patients. It has physical, cognitive and affective components; unlike normal tiredness, it is not relieved by usual sleep or rest. An assessment for reversible contributory factors such as anaemia, hypokalaemia or over-sedation due to poorly optimized medication should be undertaken. Management strategies are:

Non-pharmacological: relaxation, sleep hygiene, resting ‘pro-actively’ rather than collapsing when exhausted, and planning, pacing and prioritizing daily activities

Non-pharmacological: relaxation, sleep hygiene, resting ‘pro-actively’ rather than collapsing when exhausted, and planning, pacing and prioritizing daily activities

Pharmacological: low dose methylphenidate or modafinil (central nervous system stimulants), done in conjunction with the specialist palliative care team, may help.

Pharmacological: low dose methylphenidate or modafinil (central nervous system stimulants), done in conjunction with the specialist palliative care team, may help.

General wellbeing

Corticosteroids are commonly given as a non-specific ‘boost’ for general wellbeing, but benefits are short-lived and the adverse effects, which include proximal myopathy, are significant. If corticosteroids are to be given, then a short-term course (up to 3 weeks) to cover particular goals, with clear prescribing responsibility, is the best way to ensure net benefit.

Loss of function, disability and rehabilitation

Some of the most pressing concerns include increasing physical frailty, loss of independence, and perceived burden on others. Evidence suggests that functional problems are not routinely assessed, and not as well managed as pain and other symptoms. Rehabilitation can:

contribute to patients’ quality of life by providing strategies for managing declining physical function and fatigue, and by offering resources that might make life easier for patients and carers (e.g. equipment or a wheelchair)

contribute to patients’ quality of life by providing strategies for managing declining physical function and fatigue, and by offering resources that might make life easier for patients and carers (e.g. equipment or a wheelchair)

support patients’ adaptation to disability, helping them to increase social participation and find fulfilment in everyday living

support patients’ adaptation to disability, helping them to increase social participation and find fulfilment in everyday living

A referral to physiotherapy or occupational therapy is helpful for patients whose ability to carry out daily activities is compromised by illness or its treatment. However, remember that effective rehabilitation is a team effort and is not solely the domain of nursing and allied health professionals. Doctors also have a major role to play in attending to functional problems and fatigue; they should not see these as inevitable, unavoidable and insoluble.

There is a need to take into account changing performance status as well as changes in goals and priorities. It can be helpful to identify short-term, achievable goals and focus on these. Most patients wish to remain at home for as long as possible, and to die at home, given adequate support. Patients’ community rehabilitation needs should not be neglected.

Psychosocial issues

Depression is a common feature of life-limiting and disabling illness and is often missed or dismissed as ‘understandable’. However, it may well respond to the usual drugs and/or to non-pharmacological measures such as cognitive behavioural therapy, increased social support (e.g. day therapy) and support for family relationships. Such interventions can make a big difference to the patient’s quality of life and the ability to cope with the situation.

Extending palliative care to people with non-malignant disease

The principles of palliative care can be applied throughout medical practice so that all patients, irrespective of care setting (home, hospital or hospice) receive appropriate care from the staff looking after them and have access to SPC services for complex issues. Some principles are outlined in Box 10.4. Patients who have chronic non-malignant disease such as organ failures (heart, lung and kidney), degenerative neurological disease and HIV infection:

have a similar or greater symptom burden than people with cancer

have a similar or greater symptom burden than people with cancer

may live longer with these difficulties

may live longer with these difficulties

benefit from a palliative care approach with access to SPC for complex problems.

benefit from a palliative care approach with access to SPC for complex problems.

![]() Box 10.4

Box 10.4

Key points in palliative care

Patients should always be involved in decisions about their care.

Patients should always be involved in decisions about their care.

Quality of life is increased when treatment goals are clearly understood by everyone, including patient and carer.

Quality of life is increased when treatment goals are clearly understood by everyone, including patient and carer.

The multidisciplinary team can provide a high standard of care but there must be realism and honesty about what can be achieved.

The multidisciplinary team can provide a high standard of care but there must be realism and honesty about what can be achieved.

Hospitalization is sometimes necessary but end-of-life care is often delivered in hospices or the home.

Hospitalization is sometimes necessary but end-of-life care is often delivered in hospices or the home.

Care at home should be encouraged for as long as possible, even if the patient’s preferred place of death is elsewhere.

Care at home should be encouraged for as long as possible, even if the patient’s preferred place of death is elsewhere.

Discussions about end-of-life care planning are best held outside times of crisis, when the patient feels as well as possible, with clinicians with whom they have a good relationship. The results of these discussions must be recorded and made known to everyone involved in the patient’s care.

Discussions about end-of-life care planning are best held outside times of crisis, when the patient feels as well as possible, with clinicians with whom they have a good relationship. The results of these discussions must be recorded and made known to everyone involved in the patient’s care.

There may be a less clear end-stage of disease, but the principles of symptom control are the same: holistic assessment, reversal of reversible factors and multiprofessional support.

Patients who have non-malignant disease may have very close relationships with their usual team, and an integrated approach is essential to allow optimization of disease-directed medication as well as palliation. People with non-malignant disease may live for years with a difficult illness and so their palliative care needs to differ in some respects from those of cancer patients (Table 10.3). However, symptom management is largely transferable, with some exceptions and extra complexities as outlined below.

Table 10.3 Differences between palliative care for people with malignant and non-malignant diseases

| Cancer | Non-malignant disease |

|---|---|

Standard treatment regimens even in advanced disease |

Advanced disease often needs bespoke pharmacological interventions, which may interact with palliative drugs. Close teamwork is essential to avoid adversely affecting outcomes, e.g. in use of opioids and many other drugs |

Relatively new diagnosis (weeks to months) |

Usually many years of illness with loss of social networks, employment and practical support |

Sudden death is rare (although it can happen, e.g. pulmonary embolus, neutropenic sepsis) |

Sudden death is relatively frequent as a result of cardiovascular/diabetic complications (e.g. in chronic kidney disease) |

Cancer and associated problems are the main morbidities |

Co-morbidities due to disease or treatment often cause most problems and shape end-of-life care |

Prognosis is usually predictable |

Prognosis difficult to determine: many ‘near death experiences’, admissions and recoveries occur |

Support from SPC services is often started early in the disease course |

Main support may be from a medical unit, e.g. dialysis unit |

Standard hospice services (e.g. day therapy) often suit treatment patterns well |

Standard hospice service may not be offered (clinician ignorance) or may not be feasible (e.g. for dialysis patient attending hospital 3 days a week) |

Throughout the course of the illness, careful open discussion of possible future options is essential. Early discussion of difficult choices is as helpful for patients who have non-malignant disease as it is for those with cancer and these discussions are ideally held when the patient is relatively well and outside an acute episode. Discussions delayed until the crisis of acute admission may lead to acceptance of an invasive treatment that is later regretted by the patient.

Heart failure

There are special considerations with respect to cardiac medication in advanced disease:

Drugs that are commonly used in palliative care but usually contraindicated in heart failure, such as amitriptyline and NSAIDs, may be appropriate at the very end-of-life.

Drugs that are commonly used in palliative care but usually contraindicated in heart failure, such as amitriptyline and NSAIDs, may be appropriate at the very end-of-life.

Sudden death is more common than in patients who have malignancy and a patient may have an implanted defibrillator in place. If present, these devices should be re-programmed to pacemaker mode in advanced disease because they have not been shown to improve survival in severe heart failure and it will be distressing for patient, carer and staff if they discharge as the patient is dying.

Sudden death is more common than in patients who have malignancy and a patient may have an implanted defibrillator in place. If present, these devices should be re-programmed to pacemaker mode in advanced disease because they have not been shown to improve survival in severe heart failure and it will be distressing for patient, carer and staff if they discharge as the patient is dying.

Peripheral oedema can become a major problem and more resistant to diuretic therapy, therefore careful balancing of medication regimens is required. Ultimately symptom relief is prioritized over renal function.

Peripheral oedema can become a major problem and more resistant to diuretic therapy, therefore careful balancing of medication regimens is required. Ultimately symptom relief is prioritized over renal function.

Medications should be rationalized to reduce polypharmacy, e.g. ceasing drugs prescribed to reduce long-term secondary risk (e.g. statins) and continuing drugs that help symptom control (including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, which benefit symptoms as well as survival). Beta blockers may have to be stopped if the patient can no longer maintain non-symptomatic hypotension.

Medications should be rationalized to reduce polypharmacy, e.g. ceasing drugs prescribed to reduce long-term secondary risk (e.g. statins) and continuing drugs that help symptom control (including angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, which benefit symptoms as well as survival). Beta blockers may have to be stopped if the patient can no longer maintain non-symptomatic hypotension.

Chronic respiratory disease

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

COPD is the most common chronic respiratory disease. Patients may live increasingly restricted lives for years, rather than the months or weeks that are common once someone with cancer becomes breathless. Patients usually reach late middle age or old age before becoming very disabled, and an elderly spouse often has to carry significant physical burdens.

Because of the risk of dependency, falls and memory problems, non-pharmacological approaches to anxiety are more appropriate than benzodiazepines (Table 10.2). Short-acting benzodiazepines should be reserved for severe panic episodes.

Palliative care breathlessness services can be very helpful for those unable to comply with pulmonary rehabilitation. Emergency admissions to hospital for non-medical reasons are often due to anxiety and the support offered by community palliative care services working with respiratory teams can help prevent these.

Ventilatory support

For many patients who have respiratory failure, non-invasive ventilation has superseded the use of intermittent positive pressure ventilation (IPPV) on intensive therapy units. However, there are patients who are likely to need IPPV during admission for an acute exacerbation. For some of this group, life has become burdensome rendering the net benefit for this procedure less, or negligible. These patients should be put in contact with hospice services when they are relatively stable (not during acute exacerbations), anticipating an alternative place of admission in the event of subsequent deteriorating health.

Other chronic respiratory diseases

Other chronic respiratory illnesses that often require palliative care include:

Diffuse parenchymal lung disorders (interstitial lung disease) (ILD): this has a trajectory similar to cancer with rapidly developing breathlessness and cough. The breathlessness of ILD is particularly frightening but may respond well to opioids: early access to hospice services is particularly relevant to help with symptom control and anxiety.

Diffuse parenchymal lung disorders (interstitial lung disease) (ILD): this has a trajectory similar to cancer with rapidly developing breathlessness and cough. The breathlessness of ILD is particularly frightening but may respond well to opioids: early access to hospice services is particularly relevant to help with symptom control and anxiety.

Cystic fibrosis: patients are teenagers or young adults who usually have known their respiratory team all their lives. An integrated team involving SPC clinicians ensures good symptom control and provides useful support when difficult decisions have to be made about treatments (e.g. lung transplant), as well as offering psychosocial care to the family.

Cystic fibrosis: patients are teenagers or young adults who usually have known their respiratory team all their lives. An integrated team involving SPC clinicians ensures good symptom control and provides useful support when difficult decisions have to be made about treatments (e.g. lung transplant), as well as offering psychosocial care to the family.

Primary pulmonary hypertension: patients are often young and treated far from home in specialist centres. They require symptom control in close consultation with the medical team, and it is essential that any dependent children receive the care they need.

Primary pulmonary hypertension: patients are often young and treated far from home in specialist centres. They require symptom control in close consultation with the medical team, and it is essential that any dependent children receive the care they need.

Opioid titration in non-malignant respiratory disease

In non-malignant respiratory disease, opioid titration may need to follow a different pattern from that used in malignant disease, in which many patients are already on opioids for pain control before they develop breathlessness. The evidence is not clear but some clinicians recommend a cautious approach for these chronically breathless patients who have non-malignant disease, rather than immediately starting a daily dose of 10 mg of modified release morphine.

Renal disease

All care for patients who have end-stage chronic kidney disease (CKD) is directed toward maintenance or improvement of renal function. Prescribing is complicated, particularly if patients are receiving dialysis. Care must be taken not to inadvertently cause renal damage with potentially reno-toxic medication, and close liaison with the renal team is mandatory.

In patients who have CKD, co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes or osteoporosis may cause greater problems than the renal disease. Those with a fluctuant course of symptoms, such as the 25–33% who have co-existing cardiac disease, bear disproportionately greater physical and psychological burdens.

Patients who are on dialysis

Patients attend three times per week (and receive social support from this). Thus additional attendance at hospice day therapy service may be too tiring. If further support from SPC services is needed, then outpatient clinics, community support (for patient and/or carer) or even admission may be more suitable.

Withdrawal of dialysis

Withdrawal of dialysis is necessary if the effort of attendance becomes too great when there is little improvement in quality of life and the impact of other co-morbidities becomes intrusive.

If there is no residual renal function, survival after withdrawal of dialysis is likely to be a few days at most. In contrast, patients who have some residual function (usually those who have had dialysis for only a few weeks or months) may live for months or even a year after withdrawal. Patients and carers need to understand these differences in order to make informed choices.

Patients who are not on dialysis

Maximizing and preserving remaining renal function is a critical consideration in deciding which medications can or should be prescribed:

Medication that accelerates loss of renal function may markedly reduce survival in those patients who are able to live months or years with very little remaining renal function.

Medication that accelerates loss of renal function may markedly reduce survival in those patients who are able to live months or years with very little remaining renal function.

The renal impact of both dose and drug choice must be taken into account, e.g. morphine and diamorphine metabolites accumulate in end-stage renal dysfunction, thus strong opioids such as alfentanil or fentanyl should be used instead.

The renal impact of both dose and drug choice must be taken into account, e.g. morphine and diamorphine metabolites accumulate in end-stage renal dysfunction, thus strong opioids such as alfentanil or fentanyl should be used instead.

Close liaison with the medical team is essential for drug prescribing.

Neurological disease

People who suffer from chronic degenerative neurological diseases have considerable burden of palliative care needs including:

Difficulties in swallowing (e.g. in motor neurone disease)

Difficulties in swallowing (e.g. in motor neurone disease)

Loss of mental capacity – the ability to understand, weigh up, come to a decision and communicate that decision.

Loss of mental capacity – the ability to understand, weigh up, come to a decision and communicate that decision.

Ideally, discussions regarding the patient’s wishes should take place in advance, if the patient is able to do this, so that these can be supported.

Motor neurone disease

Motor neurone disease is usually rapidly progressive, often requiring hospice support. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (p. 222) feeding may be required. In addition, if ventilatory failure develops, nocturnal non-invasive ventilation may be offered. Patients and their carers need to understand:

why this treatment has been offered (to prevent hypercarbia and morning headache and confusion)

why this treatment has been offered (to prevent hypercarbia and morning headache and confusion)

when this treatment will be withdrawn (when it is no longer helping to maintain or improve quality of life in the face of advancing disease).

when this treatment will be withdrawn (when it is no longer helping to maintain or improve quality of life in the face of advancing disease).

Patients need to be given a clear understanding of what alternative symptom control will be offered at withdrawal.

Multiple sclerosis

Pain is often prominent in multiple sclerosis because of muscle spasm: patients may become too disabled to attend outpatient clinics and then receive very little surveillance. Hospice day therapy service, rehabilitation and support for the family can make a huge impact on quality of life.

Dementia

Dementia-related palliative care needs arise in the context of:

neurological conditions that tend to occur in older people (Alzheimer’s disease and multi-infarct dementia)

neurological conditions that tend to occur in older people (Alzheimer’s disease and multi-infarct dementia)

neurological conditions that also affect younger people (e.g. Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Huntington’s disease).

neurological conditions that also affect younger people (e.g. Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Huntington’s disease).

Dementia poses special problems with respect to inpatient palliative care. For example, in the UK, many hospice inpatient units will not accept mobile patients who have dementia because the patient’s safety cannot be guaranteed. However, they will care for those at the end-of-life with other SPC needs, for example a distressed young family or pain, and will often support other services by providing advice on symptom control.

Care of the dying

Most people express a wish to die in their own homes, provided their symptoms are controlled and their carers are supported. However, patients die in any setting and so all healthcare professionals should be proficient in end-of-life care.

Reports of inadequate hospital care have led to the development of integrated pathways of care for the dying. Pathways act as prompts of care, including psychological, social, spiritual and carer concerns in those who are diagnosed as dying. The latter is a decision reached by a multiprofessional team through careful assessment of the patient and exclusion of reversible causes of deterioration.

FURTHER READING

Department of Health. End of Life Care Strategy: promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. London: Department of Health; 2008:16 July.

General Medical Council. Treatment and Care Towards the End of Life: good practice in decision making. London: General Medical Council; 2010.

Marie Curie Palliative Care Institute Liverpool (MCPCIL) in collaboration with the Clinical Standards Department of the Royal College of Physicians (RCP). National Care of the Dying Audit – Hospitals (NCDAH) Round 2, 2008–9. Supported by the Marie Curie Cancer Care and the Department of Health End of Life Care Programme; 2009.

Do not attempt resuscitation (DNAR) orders

• The resuscitation status of every patient should be discussed by senior doctors at the time of admission and the decision documented in the notes.

• Many hospitals have specific DNAR forms. Deciding a person’s resuscitation status is a careful balance of risk versus benfit. The patient’s co-morbidities and pre-morbid quality of life should be taken into account.

• Involve the patient and family in this discussion, and explain the medical reasoning behind the decision. If the patient requests that CPR is not performed in the event of cardio-pulmonary arrest, those wishes should be respected.

Remember that a decision not to resuscitate a patient is not the same as the decision to withhold other treatment. A patient who is not for resuscitation may still be eligible for antibiotics, fluids, endoscopy and even surgery. Management should remain positive, allowing the patient to die free of distress and with dignity.

An end-of-life tool: the Liverpool Care Pathway

The Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) is a four-stage end-of-life tool designed to transfer the standard of hospice care of the dying into the hospital (Box 10.5). Now adapted for any setting, it is the most commonly used pathway for care of the dying in the UK and in several other countries. There have been no trials comparing effectiveness of any end-of-life care pathways against usual care without a pathway, but serial UK national hospital audits have been able to assess and monitor the level of care documented against the standards set in the LCP.

![]() Box 10.5

Box 10.5

Stages in the Liverpool Care Pathway – an end-of-life tool

Recognition of the dying phase

Recognition of the dying phase

Initial assessment (which includes the patient’s and carers’ understanding and psychological state)

Initial assessment (which includes the patient’s and carers’ understanding and psychological state)

Ongoing assessment and monitoring

Ongoing assessment and monitoring

Care of the carers after the patient’s death (see Table 10.2)

Care of the carers after the patient’s death (see Table 10.2)

The LCP has provision for departures from the ‘prompts of care’, e.g. discontinuation of intravenous antibiotics or parenteral fluids, if a clinical need can be demonstrated. The patient is reviewed regularly (at least daily). Occasionally, the patient improves whilst on the pathway and can be returned to usual care if this is deemed more appropriate by the clinical team. For those who do not improve, the LCP prompts advanced prescription of medication to ease the symptoms most likely to arise in the dying phase (pain, breathlessness, nausea, agitation and excess respiratory secretions) to allow timely action.

Engagement with family and carers is vital, and it should not be assumed that they will recognize or understand signs of imminent death. The LCP has supportive information leaflets that carers should find useful.

BNF. Guidance on prescribing: prescribing in palliative care. British National Formulary. London: BMJ Group and RPS Publishing http://bnf.org/bnf/bnf/current

Goldstein NE, Fischberg D. Update in palliative medicine. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:135–140.

Twycross R, Wilcock A. Palliative Care Formulary, 4th edn. Nottingham: Palliativebooks.com; 2011.