Chapter 51 Community, public health and social services

A midwife needs knowledge of community health and social services for three main reasons: to appreciate better the social context of health and how this impinges on the role; to be able to advise a woman about other services that may be helpful for her, and to refer appropriately to other services when their input would be beneficial.

Introduction

The factors influencing the health of mothers and children are broad and complex. Their impact begins long before pregnancy and will continue long after a woman’s discharge from the maternity services. Community health and social services, therefore, play an important role in the cycles of family life in many societies. Social services, community- and hospital-based health services have been through several phases of integration and separation in the UK since their establishment in the early part of the twentieth century. Currently, they are provided under quite separate institutional arrangements but much of recent health policy has focused on developing more ‘seamless’ and community-based models for providing care and this has been particularly evident in the field of children’s services. To some extent, these separate arrangements and the structures described in this chapter are products of our tendency to view health within a narrow and mechanistic framework. In consequence, health, social and other personal services, hospital- and community-based services are categorized separately, so that effort is then needed to piece them back together. The recent development of Children’s Centres in the UK is a key example of that effort. The boundaries in many of the issues discussed in this chapter are fuzzy and should be so, since that is the way health and illness are influenced and experienced by people, as part of their lives.

The importance of viewing maternal and child health in its social context

It is a common but misplaced assumption that it is provision of healthcare that is mainly responsible for our health. Evidence from a range of research disciplines, including epidemiology, social science and natural sciences, indicates that health should be viewed much more as an ecological concept; it is a product of many factors, including living environment and conditions, nutrition, occupation and education, and is profoundly influenced by maternal health. The health of mothers receiving maternity care, and of their babies, is most likely to be influenced by such issues as their nutritional status, their housing and working conditions and the level of social support available. This means that the role of maternity services is additional and relatively short term. However, it is important for midwives to remember that the effects of the short-term transition of pregnancy and birth are long-term and profound, as shown by increasing weight of evidence of the effects of maternal and fetal well-being on health in later life and between generations.

The importance of the social context on women’s health is reflected particularly clearly in the different social class patterns of health (Acheson 1998). A key example of this is birthweight; this is a useful indicator, since it is readily measurable, and is an important predictor of future health status (Oakley 1992) and low birthweight is strongly associated with poverty, inequality and lack of social support. The physical health of the mother will have been influenced by similar factors, which have a very long-term effect. Birthweight is a good example of the multifaceted nature of health, as well as the importance of social context on health (Barker 1998, Richards et al 2001, Roberts 1997).

What is meant by community?

‘Community’ is a very broad term that is currently widely used in policy developments in Euro-American societies. Generally, community is identified along three dimensions: place, relationships and sentiment or sense of belonging (Turton & Orr 1993). All contribute something to the concept, but the degree of importance attached to each is variable. When discussing health and social services, these aspects of community are all relevant, but community tends to be defined by service providers very much in service terms (i.e. the location of a service, the way in which it is delivered and its scale). Popular images of community care often take it to mean care provided at home, rather than in an institution of some type, and provided by family, friends or neighbours, rather than professionals or paid workers. To clarify these different concepts of community care – with very different implications for social policy – Bulmer (1987) drew a distinction between care ‘in’ the community and care ‘by’ the community, mostly care provided unpaid by friends, kin or neighbours, which is also referred to by service providers as ‘informal’ care.

The different areas of health services

Historically, the role of medicine has in many respects been peripheral to the concerns of public health, since it is mainly responsive to disease and concerned with the diagnosis and treatment of ill health (McKeown 1979, Stacey 1988). This is reflected in the separation of different health-related activities into the institutional spheres of social services, hospital services and community (or primary) health services.

Maternity care, and particularly midwifery, occupies a different role from much of conventional healthcare, since childbirth is an important life event and transition and pregnant women are generally understood to be healthy people, requiring care and observation for possible problems, rather than curative treatment. Nevertheless, in the latter half of the twentieth century, maternity services in the UK and other industrialized countries were organized increasingly along the lines of acute medical services, based mainly in hospitals, with women routinely referred to them by their General Practitioners (GPs) or family physicians (Hunt & Symonds 1995). Women were generally categorized into those deemed high or low risk on an agreed set of medical indicators. Care for women classified as of ‘low risk’ was then in many cases referred back to community health services – the GP and midwife – for shared care.

Following the ‘Changing Childbirth’ report (DoH 1993), a number of services in the UK moved towards greater integration of community- and hospital-based midwifery, for example through caseload practice (McCourt et al 2006) or community-based group practice (Sandall et al 2000). Additionally, during the 1990s, UK government attempts to shift appropriate areas of healthcare back into a community base led to a renewed emphasis on primary care (DoH 1997a,b; see also Ch. 4). Since 2000 in the UK, acute hospital services have become increasingly centralized. As many local communities questioned centralization of maternity services, a number of stand-alone midwife-units (Community Maternity Units in Scotland) were developed to offer care to women of low medical risk. Similar patterns of centralization, accompanied by development or re-opening of small community units have been evident in a number of countries with complex healthcare systems. In 2007 the Department of Health England offered a guarantee that by 2009, women would again be able to choose their place of birth: a home birth, birth in a local facility, including a hospital, under the care of a midwife, or birth in a hospital supported by a local maternity care team including midwives, anaesthetists and consultant obstetricians (DH 2007a).

The structure and role of community health and social services

As indicated in the introduction to this chapter, the structure of these services has been subject to a number of policy changes and varies from one country to another. The structure of the health service is described in more detail in Chapter 54.

The origins of the current system in the UK

Prior to 1946 in the UK, health and social services were largely privately paid for or charitable. The Poor Law had been the main instrument for caring for people who were disabled, chronically ill or destitute, and its operation had become punitive over time in order to discourage people from claiming relief. The nineteenth century, with rapid industrialization and urbanization, saw the growth of hospitals as places to provide healthcare, but it was not until the twentieth century that hospitals came to be seen as a desirable option in care for women giving birth (Donnison 1988). The foundations of the current welfare and health system were set down in the years following the Second World War responding to the enormous social changes taking place at that time. The NHS Act 1946 created the National Health Service, with free healthcare provided according to need, while the National Assistance Act 1948 replaced the Poor Law with a system of means-tested welfare benefits and a duty for local authorities to provide residential care for those in need. At this point, the emphasis was very much on creating the institutional structures for welfare; relatively little attention was given to community-based services – that is, support to people living in their own homes (Clements 1996).

Health services

Between 1974 and 1993 in the UK, health authorities were the main providers of health services, incorporating hospitals and some community services such as community midwifery. After the NHS and Community Care Act 1990, their role became mainly one of planning and contracting for care on behalf of the local population. Hospitals, and some community-based services such as those for people with long-term care needs, developed NHS Trust status, working independently within the health service and, in theory at least, competing with other service providers.

Following the 1997 government White Paper, ‘The new NHS, modern, dependable’ (DoH 1997a), this system was reformed again to remove the concept of an ‘internal healthcare market’ and to devolve organization of care as far as possible to a community level. The new policy introduced Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) (see Ch. 54) to commission services for their local population on behalf of the local health authority (Carnell & Kline 1999, DoH 1997a,b). After much discussion of the need for structural reform to address maternity care as a community-based service, in 2007, a report on the organization of services in London proposed four possible models of service, managed by maternity/perinatal networks, with a higher proportion of women giving birth in ‘stand-alone’ or ‘co-located’ midwife units, or at home (NHS London 2007).

Local authorities

Local authorities in the UK have a key role in planning, monitoring and developing services for the needs of the local community in a range of departments, including education, social services, housing and environmental services. All these areas have an influence on health, giving the local authority a potentially powerful role in enhancing the health and welfare of its population. In practice, the different departments have not always worked together effectively in a health-promoting role, partly because the health implications of such public services have been under-recognized. Following the NHS and Community Care Act 1990, these authorities, like health authorities, were given a more strategic role in planning services for local needs and purchasing these from independent service providers as well as continuing to provide them where appropriate. Knowledge of local authority social services is the most relevant for midwives, since social services departments have legal duties to assess people’s needs for support in the community and to provide or arrange for services assessed as being needed. The local authority social services are responsible for assessing overall community health and care needs and producing regular community care plans. They also take a lead role in child protection issues.

New structures for collaboration across community health and social services

During the late 1990s in the UK, government policy responded to research exploring the complex links between social conditions and health and the need for broad social policies to tackle these. Critical research on health education indicated that attempts to change individual knowledge and behaviour were ineffective without attention to the context of people’s lives. This was reflected in the publication of a health promotion strategy, ‘Our healthier nation’ (DoH 1998) and in new policy schemes such as Sure Start (see: www.surestart.gov.uk) and the New Deal for Communities (see: http://www.neighbourhood.gov.uk/page.asp?id=617). In 2007, the government extended the Sure Start scheme as part of an initiative to integrate and develop services for children across health and social care (DH 2004a, DES 2004) and children’s centres were developed to provide such integrated services. In some areas these are based on educational premises, and some include community-based midwifery teams or practices.

The Sure Start scheme focuses on the importance of the early years and maternal and infant health for future health, development and well-being. A number of projects were developed in areas of social and economic deprivation, and following evaluation these were extended more widely. Sure Start projects work with all families with young children but focus particularly on supporting socially disadvantaged families, with the intention of ‘breaking the cycle of disadvantage’ in the important early years of development. Examples of Sure Start schemes include family support, nutritional advice, play facilities and provision of support workers in the community (see Box 51.1, Carnell & Kline 1999, DES 2004).

Box 51.1 Sure Start scheme to support new mothers (Beake et al 2005)

Midwives working in West London teamed up with a local Sure Start programme to develop ways of promoting maternal and infant health. The Coningham Sure Start programme pioneered a scheme to increase breastfeeding and reduce smoking in new mothers by providing hands-on support from an Infant Feeding Support Worker. She works closely with midwives and health visitors, visiting women at home and running groups, on a long-term basis, from pregnancy to the months following birth. Developing the project brought together midwives who work with a personal caseload of women in a socially deprived area and health visitors who work with a strong public health focus as part of the Sure Start team. Previously, contact was limited, despite the overlap of roles and interests in promoting the health of mothers and babies, due to the handover of care at about 10–28 days following birth, and by working for different organizations. Community-based schemes like this one, with midwives able to follow women across traditional boundaries such as hospital–community or high–low risk and to plan and provide care around their needs, may be one basis for midwives to develop the more health-promoting focus that has always been seen as an ideal.

The aim of Sure Start

To work with parents-to-be, parents and children to promote the physical, intellectual and social development of babies and young children – particularly those who are disadvantaged – so that they can flourish at home and when they get to school, and thereby break the cycle of disadvantage for the current generation of young children.

Schemes such as the New Deal for Communities are more broadly based regeneration schemes applied to areas with high levels of, often multiple, disadvantages and low levels of ‘social capital’: informal and other social resources for communities to build on. Following the lessons of earlier attempts to ameliorate the negative effects of poverty with single measures, these projects integrated areas such as health, housing, employment, leisure, child care, education and nutrition or food access schemes – all areas of disadvantage that tend to have a cumulative or ‘spiral’ effect.

The midwife’s role in relation to community health and social services

Midwives are in a good position to provide general care and support to the woman during a period of great personal and social adjustment as well as physical change. In addition to clinical skills, midwives provide information and advice and, in many cases, social support. Such a role has the potential to provide a positive impact on the general health and wellbeing of women and their families during a period of change and development. Midwifery care is relatively short term but interventions during certain critical periods may have a long-term impact, however small. A good example of this is the midwife’s role in health promotion and in supporting women in feeding their babies (Crafter 1997).

When a woman needs more general sources of advice and social support than those provided through the maternity services, midwives can still play a key role in providing relevant information and advice and in referring her to other professionals and organizations for support. This role is underpinned by:

Public health role of midwives

Government policy has recognized the difficulties caused in practice by the institutional split between health and social and community services and advocated returning maternity services towards a more seamless model of care. The National Service Framework (NSF) for Children, Young People and the Maternity Services (DH 2004a) advised a stronger public health role for the midwife, through changing the organization of care and expanding the scope of the midwife’s roles and responsibilities. Although it did not set out the precise nature of this expanded role, or how it would be achieved, it recommended more integrated models of care, with midwives working across hospital and community service boundaries, for example, with personal or group practice caseloads, or with specialist roles. The framework also advocated a stronger public health role, in collaboration with other primary care practitioners, with an increased focus on health promotion and additional support to socially disadvantaged women. This emphasis was reinforced by the findings of successive reports on maternal and infant health, which (e.g. Lewis 2007) indicated that contributory causes of maternal death in the UK were social exclusion, deprivation, social and mental health related problems. The health promotion role advocated for midwives was particularly through health education for women and through focusing care more effectively on women with particular needs for support arising from problems such as domestic violence or substance abuse.

Although much of midwives’ work is primary, preventive healthcare, to date there has been little involvement of midwifery in this new focus on primary and preventive health services. Development of more integrated, child and family-centred services, such as children’s centres, may help to support more public health-focused roles. Similarly, while health visitors and midwives have tended to work separately in recent years, one following on from the other, such community projects and the proposals for extended public health roles for midwives may involve them in more collaborative ways of working together (e.g. Box 51.1).

The legal framework

Community health and social services operate within a legal framework (Acts of Parliament) set out by government. Local and health authorities are provided with guidance to follow in interpreting and implementing the legislation. Guidance is normally mandatory, for example Executive Letters issued by the Department of Health, whereas guidelines are advisory (e.g. good practice guides), to assist with the complexities of putting policy into practice. UK legislation also operates within the framework of European (EU) legislation and policy directives and is increasingly expected to develop in line with this framework. The relevant frameworks in other countries will differ, but it is important for all midwives to become familiar with the legal framework in their own country of practice.

Relevant legislation

The main relevant legislation in the UK at the time of writing is shown in Box 51.2 The central pieces of legislation for practitioners in the UK are the Health and Social Care Act 2001 (DH 2001), which set out a newly combined framework for health and social services – the National Health Service Act 2006 and the Commissioning Framework – which operationalized its principles (DH 2006a). The key aims were to integrate the different services better and to improve organization of services for people with care needs, particularly since many services are now community based. Many health problems are not easily divided into health and social care needs.

Box 51.2 The UK legal framework for community health and social services

Care management

In the UK, anyone who comes to the attention of the local authority or health service as having possible needs for support is entitled to an assessment, followed where appropriate, by a plan for care, which should include an integrated ‘package’ of services. This is referred to as a ‘personal health and social care plan’ (DH 2006b). The principle is that the needs of the person should be central and services should be sought to respond to these needs, rather than fitting people into the services. A midwife can request or assist a woman or family in requesting a care assessment. The needs for support – and the possible solutions – can be quite wide-ranging, including ‘home help’ and additional childcare. Assessment should involve the woman, her family where appropriate, and all relevant professionals, who may include the community midwife. If she, or her child, is considered to have care needs, a care manager will be appointed to ensure that adequate and suitable support services are arranged. Care managers are often social workers but they may be other professionals (including home care organizers, community nurses or midwives) according to the nature of the individual’s needs. In 2006 the UK government introduced a plan for joint health and social care managed networks and/or teams for people with complex needs and in 2007, they introduced the role of Community Matron, with the aim of improving case management of people with long-term health or social care needs, and improving integration of services across boundaries such as primary and secondary health services, health and social care.

As Community Matrons are appointed it will be useful for midwives to familiarize themselves with their developing roles, and to establish contact, since midwives may care for women in pregnancy who have other, often complex health and social care needs. It is also important to try to anticipate needs (such as a woman needing home help after birth or an infant needing support for physical impairments) well in advance and encourage and support the woman to seek additional support when needed. Some services may be charged for on a means-tested basis and there is considerable variation in provision according to where people live. Needs for care are not tightly defined because they are meant to be broad, but generally the policy is aimed at people (adults and children) who have physical, sensory or intellectual impairments, chronic health problems or mental health problems, or who care for people with such problems. Pregnant women and those who have recently given birth are included. Those who are providing regular and substantial care for friends or relatives, informal carers, are also entitled to an assessment of how they are affected by their caring responsibilities (Clements 1996, Dimond 1997).

Maternity rights and benefits

In most countries, women are entitled to a series of benefits and have particular rights during pregnancy and childbirth regarding employment. In EU countries these have increased in recent years. Midwives are in an ideal position to advise women of their general rights and entitlements and to respond in a timely fashion to requests for information on rights and benefits and on where to go for further help.

The Benefits Agency (BA)

The Benefits Agency works at national level on behalf of the UK government’s Department of Work and Pensions (formerly the Department of Social Security). It assesses needs for financial support, in line with national legislation, and provides payments, exemption certificates and loans where appropriate. It is responsible for the administration of maternity benefits of various types. Local offices and telephone lines are provided for information and enquiries.

Although the overall framework of rights and benefits is relatively stable, details may change from year to year. A checklist of sources of information and advice is important, as is regular renewal of the forms and information leaflets provided by the BA. For these reasons, it is crucial not to rely on a textbook; however, the following section summarizes the system of rights and benefits in the UK in operation in 2007.

Maternity rights

Women’s rights at work are set out in UK law and in EU directives. Where the two differ, UK law is generally expected to comply with EU directives, unless it provides for greater rights. Maternity rights also operate within the broader framework of employment and discrimination law (IDS 2007). They include employment protection, health and safety, paid time off for healthcare, rights to maternity and parental leave and rights to return to work (Box 51.3). Detailed but clear and accessible information on maternity rights is available in the following leaflet:

Box 51.3 UK maternity and employment rights at 1 April 2007 – key points

Protection of employment

A woman with a contract of employment cannot be dismissed from her job for being pregnant or on maternity leave. She maintains general employment rights including protection against discrimination. Further advice can be obtained from the ACAS helpline on 08457 474747.

Health and safety

Employers are responsible for ensuring health and safety at work for women who are pregnant or breastfeeding, or, if not practicable, must provide suitable alternative work or suspension on full pay. Detailed advice can be obtained from //www.hse.gov.uk or the health and safety information line on Tel: 0845 345 0055.

Leave

A woman is entitled to paid leave for antenatal healthcare, including home visits and parent education or preparation classes. An employer may request verification of appointments. All employees are entitled to maternity leave for up to 52 weeks, and a minimum 2-week period is compulsory (4 weeks in factories). Fathers are also entitled to take up to 2 weeks paid paternity leave.

Right to return

A woman has a right to return to her previous job, on no less favourable terms, provided she complies with limited conditions of notice and returns within the statutory periods of leave. There are some limited exceptions to this rule. Parents may also request more flexible working arrangements and provisions for time off for care for dependents.

This and other useful guidance can be accessed at: www.direct.gov.uk

For those with computer access – at home, at work or perhaps through a local library or community centre – the government has set up an interactive website that can be used for general information and more personalized advice: www.tiger.gov.uk.This will be an excellent resource for midwives as well as for pregnant women. It can be used by women to get a good idea of the benefits they are be entitled to.

Maternity benefits

These include monetary and non-monetary benefits (benefits in kind or exemptions). The key monetary benefits related to maternity are set out in Box 51.4. The changes in family circumstances due to childbirth may also mean changes in entitlement for families that rely on housing benefit, working families tax credit or income support because of low incomes. Generally, each additional child increases entitlement and may sometimes mean the difference between qualifying for a benefit and not. Since women may seek advice on any of these benefits, or general advice about coping with new economic demands, it is important to obtain a full set of advice leaflets. Entitlements and benefits are liable to change from one year to another owing to legal and policy changes as well as inflationary increases in benefit levels, so it is important to update all leaflets, and one’s own information sources, annually. Detailed information on maternity benefits can be found in the information booklets NI 17A Guide to maternity benefits and BC1 Children and benefits, which are available from local BA offices and most post offices.

Box 51.4 Monetary maternity benefits in the UK – at April 2007: key points

Statutory Maternity Pay (SMP)

This is payable to women in continuous employment and earning above the statutory limit for National Insurance contributions before the pregnancy started. Payment is for up to 39 weeks at a level equivalent to 90% of earnings for 6 weeks followed by a lower flat rate, set annually, and can commence at any time from 11 weeks before the expected week of confinement (EWC), or earlier if the baby has been born. It is administered by employers, who should be given 15 weeks’ notice of the intended date for taking leave (although the date can be amended up to 28 days before leave). Women continue to be liable for tax and national insurance, and employers must continue to pay pension contributions.

Many employers, especially large organizations, operate more generous schemes than the statutory minimum. The woman should check these terms and whether they apply to her with her employer or human resource department in good time.

Maternity Allowance

This is paid to women not entitled to SMP but who have paid National Insurance contributions during the qualifying period. It is paid weekly for up to 39 weeks, at a flat rate or 90% of earnings, whichever is lower. Application must be made on form MA1 accompanied by forms MATB1 and SMP1 (which is issued by the employer) from 26 weeks of pregnancy and before leaving work. Women not entitled to either SMP or MA may be able to claim Incapacity Benefit or Income Support during their leave period.

Sure Start Maternity Grants

Women who receive income support, income-based jobseekers allowance, working families or disabled person’s tax credit can claim a single payment to assist in the costs of a new baby. The grant is payable from 29 weeks of pregnancy and must be claimed before the baby is 3 months old or within 3 months of adoption.

Checking entitlements

Up-to-date details of benefits and entitlements can be obtained by using the local BA office or an independent advice agency. Some local authorities employ welfare rights advisors, who have in-depth knowledge of rights and benefits and who can undertake casework where needed.

Pregnant and childbearing women are also entitled to a range of non-monetary benefits, such as vitamins, some of which are universal (i.e. all are entitled) while others are available only to those who are entitled to income support or family credit. The previous ‘welfare foods’ provision is now referred to as Healthy Start, and vouchers available for young mothers and those on low incomes can be exchanged for a range of healthy foods (see: www.healthystart.nhs.uk).

Forms and certificates to be supplied by the midwife or GP

Midwives or GPs are responsible for providing the certificates that the woman will need to exercise her employment rights and claim relevant benefits. These include:

Complete the checklist given in Box 51.5, to function as a ready reminder of where to go for information.

The community health services

Community health services encompass what is generally known as primary healthcare. They include community-based services for health promotion, such as child health clinics and school health services, and for longer-term health needs, such as mental health centres. The philosophy of the 2006 policy paper ‘Our health, our care, our say’ (DH 2006b) relates closely to the reality of health needs, which do not fit easily into professional or organizational categories and it attempts to put the person at the centre of services. The development of Children’s Centres will also see greater opportunities for integration of services for families of young children. Children’s Centres will be based mainly in Sure Start schemes or other local services, such as schools, and will offer a base for antenatal services, early years care, parent support and other services relevant to young children and their parents. A range of professionals will be based in these centres, or use them as a sessional base, so facilitating greater contact between different professionals as well as easier access for families.

The GP and the GP practice

In the UK, GPs provide much of the everyday healthcare for families and act as the key gatekeepers for secondary healthcare. GPs are independent professionals, who contracted into the health service after its inception in 1948, while maintaining much of their independent status (see Ch. 54).

GPs and maternity care

In the early part of the twentieth century GPs had little involvement in maternity care, since birth was largely managed by midwives. Many women could not afford a doctor’s fees and some doctors, in any case, had arrangements with local midwives, delegating care for uncomplicated births (Leap & Hunter 1993, Robinson 1990). After increasing in importance during the century, the role of GPs in childbirth declined from the 1970s. The Peel report (MoH 1970) and the Short report (House of Commons 1980) had advocated a shift of all maternity services to consultant-led hospital units and the closure of small GP-led units or cottage hospitals, despite lack of research evidence that they were less safe (Tew 1990). More recently, centralization of care into larger obstetric units has taken place, but Midwife Units or Community Maternity Units have been developed to provide more local care for women of low obstetric risk. Similar patterns of development have been evident in many countries with ‘developed’ healthcare systems.

Except where a GP has a particular interest in birth, GPs are now mainly involved in antenatal care, which they may share with a practice-linked community midwife, group practice or caseload midwife. A 2007 review of services advocated a set of models appropriate to women with different levels of obstetric or social risk, including a more primary care-based pathway for women of low obstetric risk, with choice of birth at home, in Midwife Units, or an obstetric unit (NHS London 2007), reflecting the direction of development set out in Maternity Matters (DH 2007a).

Health visitors and child health services

Health visitors are registered nurses or midwives who specialize in health promotion and advice for families with children under 5 years and, sometimes, older people. The health visitor’s role can, however, be applied to the positive or preventive health needs of the local community in general in that it focuses on health education and prevention of ill health rather than responding to illness and so is proactive – looking for health needs – rather than reactive. Four key principles of health visiting were outlined in 1977 and confirmed by the Health Visitor’s Association and the Standing Conference on Health Visitor Education in 1992:

While health visiting means working with communities and taking political action, in addition to working with individuals and families, in practice, the collective aspects of their role have been less well developed. However, the Sure Start initiative provides a route through which health visitors are increasingly becoming involved in such community-oriented, health promotion work (Cowley 2002). The pathfinder Children’s Trusts, for example, set up to implement principles of Every Child Matters (DES 2004), are focused in areas of social deprivation, and aimed to provide more integrated and accessible support services, and health visitors have a key role in these. An initial evaluation of these has suggested positive potential (UEA/NCB 2007) and the UK government plans to roll-out their development more widely, often based in Sure Start Children’s Centres.

Health visiting in the UK had its origins in the nineteenth century social reform movement that was a response to the problems of rapid industrialization, urbanization and poverty (Robertson 1988). Concerns about public health also led to improvements in general sanitation (especially sewerage and water supply) and housing conditions. The most important moves towards improving public health and decreasing the high mortality due to infectious diseases were, therefore, set in place as a result of careful observation of living conditions, before the precise mechanisms of infection were understood (McKeown 1979). Modern health visitors continue this public health role and increasingly focus on psychosocial care and on the health effects of inequality as well as the more traditional concepts of public health.

Health visitors visit families to give advice or support and run health clinics. In some areas health visitors visit women during pregnancy to offer health advice and preparation for parenthood, or provide parent education classes jointly with community midwives. They may also play a role in providing preventive support or referral for problems such as postnatal depression.

After a baby’s birth, in the UK, the parents are given a child health record book to keep, along with general information about community health services, and are invited to visit the child health clinic regularly.

The broad remit of health visitors, including screening, health education and prevention roles for the local population, gives them a less clearly defined professional identity than some other health professionals, and their roles are likely to change with the advent of integrated Children’s Centres and moves towards development of more integrated professional roles. They are increasingly encouraged to work with existing or potential social support networks, rather than to attempt to provide all support themselves or adopt the role of experts. This connects to a wider debate about the nature and effectiveness of health education and promotion programmes. This is reflected in their roles within Sure Start projects, or developing links with wider regeneration projects that reflect a broad health promotion role and a renewed emphasis on tackling the problems of poverty and social exclusion (see Box 51.1, also Cowley 2002). However, like other professionals, health visitors also have to balance potentially conflicting roles of providing support and monitoring or surveillance of families. Such dilemmas are faced most acutely when considering child protection issues.

Health education and preventive healthcare

While community health services such as health visiting and midwifery aim to focus on preventive healthcare, they also encounter the basic problems confronting health professionals in attempting to provide health education and preventive care as some women may also view it as an unwarranted interference in their lives.

Preventive healthcare has been described as operating on three levels:

Pregnancy and adaptation to parenthood are important life changes and a time when adults are particularly responsive to information and often seek it out actively. Nonetheless, health education, as traditionally conceived, has the important limitation of tending to focus on individual lifestyles and desired behavioural changes, outside the context of the constraints on people’s lives and the ways in which such conditions affect health. For example, the ‘Health of the Nation’ document (DoH 1992) sets out clear priority areas and targets for reduction of morbidity and mortality, but was criticized for its emphasis on altering individuals’ behaviour in the absence of structural changes to promote healthy lifestyles or increase individual choices. The following government document ‘Our Healthier Nation’ (DoH 1998) responded with a far greater emphasis on the conditions that produce ill health and this is also reflected in more recent government policies for health and social care, as described above.

Crafter (1997) distinguished health education, which largely involves working with individuals or groups to enhance or change knowledge, with the aim of helping people to make informed and positive health choices, from health promotion, a broader concept that recognizes the importance of social and environmental influences on health. To promote positive health, it is increasingly acknowledged that health education must work hand in hand with efforts to change the structural and environmental factors influencing health, either directly or through the choices people feel able to make. Principles for health education are set out internationally by the World Health Organization and these have shifted since the 1980s towards involving individuals and communities in planning and implementing healthcare. The Ottawa Charter, for example, states:

health promotion works through effective community action in setting priorities, making decisions, planning strategies and implementing them to achieve better health. At the heart ofthis process is the empowerment of communities, and the ownership and control of their own endeavours and destiny. (WHO 1986, p 1, quoted in Jones & Sidell 1997.)

Immunization

Immunization is an important aspect of preventive healthcare globally. There are different forms of immunization, but they all function through stimulation of the immune system in order to enhance resistance to a particular mechanism of infection.

Vaccines are available for a range of diseases, some of which have severe symptoms (e.g. polio), whereas others are important for protection against congenital defects. Immunization against rubella (German measles) is a good example of protecting a vulnerable group, namely pregnant women, by means of protecting the general population. While the disease produces only mild symptoms in children and adults, it has severe implications for early fetal development. Immunization thus has a dual role in public health:

Although population protection is arguably the most important function of immunization, epidemiologists have pointed out that, historically, its role in improving public health and decreasing mortality has been overestimated in relation to more general measures such as improved nutrition and sanitation (McKeown 1979).

A series of immunizations focusing on the most common and the most potentially damaging childhood illnesses is offered to all children in the UK from about 8 weeks of age. Since women may ask for advice about immunization during their postnatal care, it is important for midwives to increase their own knowledge of its benefits and limitations, recommended practice and contraindications for certain individuals.

Since immunizations can, rarely, have serious side-effects, parents should always be advised about contraindications and precautions when they are encouraged to take up immunization. Parents are particularly likely to raise questions about vaccinations that have been subject to controversy. The pertussis vaccine, which protects against whooping cough, was a focus of concern regarding severe side-effects during the 1970s, which led to a significant fall in take-up rates. Subsequent studies have failed to confirm the level of risk conclusively and policy documents have emphasized the high level of risk from the disease itself in relation to possible vaccination risks. The combined measles, mumps and rubella vaccine (MMR), introduced during the 1990s as a mass immunization programme, has also been controversial, with some professionals arguing that the programme was speculative and unnecessary in view of possible side-effects and others arguing that considerable research has shown few ill-effects and considerable benefits, and that the seriousness of some diseases are now easily overlooked by modern populations. Currently, although a number of parents may enquire about separate vaccinations, Department of Health advice is that combined immunization is safer, and separate vaccines are not provided by the NHS (DH 2004b). In all such cases, the complexity of influences on public health means that definitive evidence on the benefits and risks of immunization is hard to obtain. Current policy remains that, on the balance of evidence, the benefits to public and individual health greatly outweigh possible risks. Up-to-date advice on immunization and current versions of schedules can be obtained from the NHS at www.immunization.org.uk

Social services

The local authority social services departments hold the main responsibility for community care arrangements, liaison with health services and support for specific needs and problems such as childcare and protection, although the services arranged to meet such needs may be provided by a range of organizations. Facilities provided or contracted for by social services include home care, respite care, and day and residential childcare.

Social workers

Social workers play a key role in community care and also have specific statutory duties with respect to mental health and child protection. They also act as gatekeepers to other services, such as home help or assistance with child care. They may also provide direct support to clients, using a casework approach. Most social workers have a generic role that is concerned with a range of client groups although some work as specialists. This is more common in mental health social work, where some qualify as Approved Social Workers and are obliged to carry out statutory assessments under sections of the Mental Health Act 1983 and in child protection.

Social work, like health visiting, has its origins in social reform movements. The approach of social work in the UK today was laid out when local authority social services departments were created following the Seebohm report in 1970 (Clements 1996). The main areas of social work relevant to midwives’ work are their childcare and protection and their mental health roles. These roles operate within the frameworks of the Children Act 2004 and the Mental Health Act 2007.

Child protection and families needing support

In general, the aim of social services is to provide support to families that will help them to manage their situation and prevent the need for more extensive services or interventions. A good example of this would be the provision of respite care (care for short breaks), home care, and aids and adaptations in the home for parents whose child has a disability, which may avoid the need for residential care. These aims are not always met in practice owing to funding shortfalls or simply because of problems in coordination of services. Midwives can promote good practice by advising women of their rights to apply for assessment for services and supporting them in the assessment process.

The Children Act 2004 in the UK focused on the needs of the child and emphasized that childcare services or proceedings should always consider their welfare and interests as paramount. For example, it states that court orders should be made only where it is in the interests of the child to do so. The policy aims to support families so that they can remain together where possible and provides guidance on appropriate social service responses where this may not be in the interest of the child.

The Children Act 2004 provided the legal underpinning to the policy guidance Every Child Matters (DES 2004). Its focus was on children’s well-being and defined five key outcomes, which were developed more fully in the Every Child Matters guidance: Be healthy; Stay safe; Enjoy and achieve; Make a positive contribution; Achieve economic well-being. This policy was also intended to work in close synergy with the health policy priorities set out in the NSF (DH 2004a) to ensure that children’s services are truly integrated. The 2004 Children Act replaced a ‘needs’ focused approach with a more child- and family-centred approach that regards all children as having positive needs for development and well-being and Every Child Matters aims to help professionals to form a view of what children need to thrive, whatever their social or cultural background. When a child has particular needs by virtue of disability or other problems, social services departments have a duty to respond. Since midwives have close contact with women and their families in the perinatal period, they may have an important role in identifying where families need additional support and advising those with special needs (DES 2004).

Child protection procedures

However, positive its intended focus, such legislation has to clarify professional responsibilities and actions in cases where there is concern that children’s wellbeing is not being protected. The Act established Local Safeguarding Children Boards (LSCBs) to be set up by each Local Authority, as part of the wider context of Children’s Trust arrangements, and details are set out in the Working Together to Safeguard Children document (HM Govt. 2006). This guidance (and Section 11 of the Children Act 2004) made clear that all agencies have shared responsibilities and duties to make arrangements to safeguard and promote the welfare of children and emphasized the importance of joint working to achieve this. Although the primary duty is with each local authority, all professionals who come into contact with children have duties to promote its general principles:

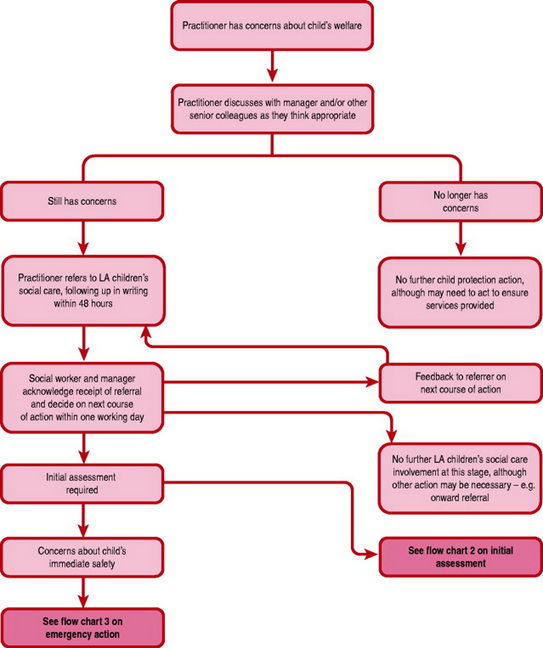

Midwives need to be aware of child protection procedures (Fig. 51.1) since they are likely to be in contact with families that pose serious concerns about the child’s welfare. The Working Together to Safeguard Children document provides detailed advice on actions to be taken and routes of referral for any professionals who develop concerns about the welfare of a child. It advises that all health professionals who work with children and families should be able to:

Figure 51.1 The child protection process: initial referral. (© Crown copyright. Working together to safeguard children 2006).

The guidance, therefore, or equivalent guidance in other countries, should be read and retained for reference by all midwives.

The distinction between the need for support and the need for child protection is a difficult one and, in many situations, adequate and timely support for a family can prevent the need for child protection measures. The transition to parenthood is an important life event for all parents, and life events, even where they are wanted and viewed positively, can be major sources of stress and emotional distress (McCourt 2006). Childcare and adjustment to parenthood present a challenge to most parents and there is no clear and simple line between those who are able and those who are unable to cope with the demands of a new baby. However, there are circumstances that have been shown to be strongly associated with parents’ capacity to care for a child, in particular families with multiple problems (Cleaver et al 1999).

Compulsory intervention is advised in cases where there is concern about significant harm to the child (Children Act 2004, HM Govt. 2006). Where midwives are concerned about possible significant harm, they should normally contact the relevant Local Authority, or their Local Safeguarding Children Board (LSCB). In the first instance, concerns can be raised with the supervisor of midwives or with the named senior midwife with responsibility for child protection, who should ensure that the appropriate social services officers are contacted. Each Primary Care Trust is responsible for ensuring that health service providers have clear policies in place, and each PCT and NHS Trust should appoint a lead nurse or midwife and a lead doctor for child protection. Each midwife in the UK should be familiar with these policies and key contacts. In emergencies out of hours, police child protection teams may be involved or an Emergency Protection Order may be sought. The midwives code of practice also provides basic guidelines to appropriate conduct.

Midwives may become concerned about potential child abuse antenatally, influenced by factors in the woman’s history, her current mental state or her living situation. This may include concerns about domestic abuse towards the woman herself, and research has shown that there are strong associations between situations of domestic abuse and child abuse (Cleaver et al 1999). Antenatal care is a good point at which to work with a woman and to provide support, or assist the woman in obtaining the support she needs, in order to prevent possible problems arising after the baby is born. Indeed many of the family problems that are often associated with higher levels of abuse are those where parents, mothers in particular, would benefit from high levels of ante- and postnatal support. Interventions to support women with mental health problems, substance abuse problems and those who suffer from social isolation, poor support or domestic abuse are important preventive and health promoting measures (DH 2004a). In cases of concern about significant harm, a Child Protection Conference may be called regarding an unborn child, and midwives are particularly likely to be involved in such cases (HM Govt. 2006).

Identifying possible child abuse

Abuse is difficult to define and even more difficult to judge. The incidence of abuse is difficult to measure since it depends on reporting or detection; that is likely to be related to social awareness and policy as much as anything else.

Recent UK research has shown that, although abuse is very widespread and is by no means confined to particular social groups, when child protection cases reach court proceedings, high rates of identifiable parental problems such as mental illness, domestic or substance misuse are found. Domestic abuse is an important issue in its own right and is also associated with increased risk of child abuse and it is estimated that one-third of domestic abuse commences or escalates during pregnancy. For both reasons, it is important for health professionals to respond to signs of possible domestic abuse. Women may often present problems but in an indirect rather than overt manner, such as repeated visits to health providers complaining of vague illness symptoms, or through self-harm or symptoms of mental distress (NCB 1995, Turton & Orr 1993). Rates of child abuse are particularly high where families are experiencing multiple problems. None the less, the majority of mothers with such problems are able to care for their children well, particularly if they have support from their partner or family, and supportive services to turn to (Cleaver et al 1999).

This evidence lends further weight to the current emphasis in child protection on prevention and efforts to work with families. It is helpful if problems are not seen as resulting from a dichotomy in parenting styles but as occurring on a continuum from calm and confident parenting through the normal range of most parents to those who have great difficulties and potential for abuse. It also highlights the potential value of appropriate midwifery support in pregnancy. It is important for midwives to respond to early signs of stress or distress in pregnant and postnatal mothers and their families, by being ready to listen and to provide advice and information or referrals to other sources of support, including self-help groups.

Robertson (1988) argued that health visitors dealing with child protection should work within a framework of cross-cultural and societal violence and should maintain a focus on prevention. By this she meant understanding that child abuse is not just an individual issue but takes place within the framework of social and cultural conditions and values. Professionals should focus on the basic needs of the child and on the child per se and avoid relying on subjective judgements about what constitutes good or appropriate parenting, which are strongly influenced by cultural norms (Cloke & Naish 1992, Narducci 1992). It is tempting to believe, particularly as a service provider, that one’s own knowledge and values are naturally right or superior.

Child abuse can be identified in various forms and, although problems tend not to fall into neat categories, in practice these may be of use in assessing possible abuse. The categories used in government policy are listed in Box 51.6.

Box 51.6 Categories of child abuse (HM Govt. 2006, p 37–38)

Physical abuse

May involve hitting, shaking, throwing, poisoning, burning or scalding, drowning, suffocating, or otherwise causing physical harm to a child. Physical harm may also be caused when a parent or carer fabricates the symptoms of, or deliberately induces, illness in a child.

Emotional abuse

The persistent emotional maltreatment of a child such as to cause severe and persistent adverse effects on the child’s emotional development. It may involve conveying to children that they are worthless or unloved, inadequate, or valued only insofar as they meet the needs of another person. It may feature age or developmentally inappropriate expectations being imposed on children. These may include interactions that are beyond the child’s developmental capability, as well as overprotection and limitation of exploration and learning, or preventing the child participating in normal social interaction. It may involve seeing or hearing the ill-treatment of another. It may involve serious bullying, causing children frequently to feel frightened or in danger, or the exploitation or corruption of children. Some level of emotional abuse is involved in all types of maltreatment of a child, though it may occur alone.

Sexual abuse

Involves forcing or enticing a child or young person to take part in sexual activities, including prostitution, whether or not the child is aware of what is happening. The activities may involve physical contact, including penetrative (e.g. rape, buggery or oral sex) or non-penetrative acts. They may include non-contact activities, such as involving children in looking at, or in the production of, sexual online images, watching sexual activities, or encouraging children to behave in sexually inappropriate ways.

Neglect

The persistent failure to meet a child’s basic physical and/or psychological needs, likely to result in the serious impairment of the child’s health or development. Neglect may occur during pregnancy as a result of maternal substance abuse. Once a child is born, neglect may involve a parent or carer failing to: provide adequate food, clothing and shelter (including exclusion from home or abandonment); protect a child from physical and emotional harm or danger; ensure adequate supervision (including the use of inadequate care-givers); ensure access to appropriate medical care or treatment. It may also include neglect of, or unresponsiveness to, a child’s basic emotional needs.

The UK policy guidance notes that there are no absolute criteria for judging significant harm but advises that:

Consideration of the severity of ill-treatment may include the degree and the extent of physical harm, the duration and frequency of abuse and neglect, the extent of premeditation, and the presence or degree of threat, coercion, sadism and bizarre or unusual elements. Each of these elements has been associated with more severe effects on the child, and/or relatively greater difficulty in helping the child overcome the adverse impact of the maltreatment. Sometimes, a single traumatic event may constitute significant harm, e.g. a violent assault, suffocation or poisoning. More often, significant harm is a compilation of significant events, both acute and long-standing, which interrupt, change or damage the child’s physical and psychological development. Some children live in family and social circumstances where their health and development are neglected. For them, it is the corrosiveness of long-term emotional, physical or sexual abuse that causes impairment to the extent of constituting significant harm. In each case, it is necessary to consider any maltreatment alongside the family’s strengths and supports.’

Signs and symptoms of abuse are not always clear. Bruising, for example, may be the result of a range of causes and suspicion of abuse is more likely if the bruising forms a particular pattern. The signs are more likely to be taken seriously if a number of symptoms are found together or where inconsistent accounts of accidents are given and where there are delays in seeking care (Robertson 1988).

Fostering and adoption

Midwives often provide care for women whose pregnancy was not planned. This is more common than many professionals may realize and it is important not to make assumptions about the woman’s feelings about her pregnancy. For example, in a study of women’s experiences of maternity services, between 22% and 40% of women in the groups studied had mixed or negative initial feelings about the pregnancy (McCourt & Page 1996). In many cases women will be happy about an unplanned pregnancy, whereas others may be ambivalent and need support and possibly non-directive counselling to assist them in making decisions and plans for the future. For some women, this may involve relinquishment of the child for adoption. It is important to remember that such women share ordinary needs for information and support in pregnancy and childbirth, as well as having additional needs for support around relinquishing their child. Midwives can make a difference to how women feel in quite simple ways, such as avoiding judgmental or insensitive comments or approaches to care, by offering women a chance to discuss their situation privately but openly, and by providing advice on where they might find more specialized support.

Adoption procedures were reformed by the Children Act 1989 and 2004 so that there is now a greater emphasis in the UK on open adoption where possible, so that relinquishing mothers may remain in agreed forms of contact with their children. Practice in childcare agencies has also developed in recent years so that children who are adopted, fostered or placed in residential care are given more opportunity to understand and talk about their personal history. Fostering (on a short- or long-term basis) may be a consideration for mothers who are unable to care for their babies after birth but who do not wish to relinquish their children for adoption. The Children Act also increases flexibility for family members to care for children or remain in contact with them where mothers are unable to do so.

Other community services

Childcare services

Childcare services may be important in providing support to families experiencing stress, for example due to poor or temporary housing, caring responsibilities or postnatal depression. Childcare services for children under 5 years old are mainly the responsibility of social services, although education departments may manage local authority provision for children aged between 3 and 5. They generally provide a limited number of places but are responsible for the registration and inspection of all other facilities for the under 5s in their local area, including privately owned nurseries and individual childminders. Some services, often run by voluntary agencies, are also geared to the needs of families under stress. These include family centres, where parents and children can attend together and receive parenting support, and schemes such as Homestart or Newpin (Family Welfare Association) and Sure Start Children’s Centres.

Social services departments often provide under-5s advisors. Local authorities often publish guides to local child care facilities, not only day care but resources for parents and small children to use together, such as playgroups or toy libraries and crèche facilities linked to adult education or sports activities. The UK government’s Sure Start website gives some useful and regularly updated information on finding and using child-care.

Interpreting, advocacy and link workers

Women and families from minority ethnic communities have two closely related sets of needs from maternity and other community health and social services (see Ch. 3). First are the ordinary needs, which they share with women of all backgrounds but which are often attended to more poorly owing to language or cultural barriers or to discrimination. Second are the particular needs resulting from their minority status, which may include language access and more specialized services. In practice, both are likely to be related. For example, women in a small-scale study of a refugee community in West London voiced concerns about lack of information, advice, choices and sensitive personal care. These concerns were widely shared among local women but they were experienced as far more severe problems by women from ethnic minorities (Harper-Bulman & McCourt 2002).

Women who are refugees may also be socially isolated and need practical support in adjusting to life in a new country. Many will have come from situations of fear and conflict, only to meet with the difficulties of the asylum process on arrival. There is debate around the psychological health status of refugees, between those who emphasize the likelihood of post-traumatic stress and the need for psychological interventions such as counselling, and those who argue that medical approaches to the needs of refugees are not necessarily or always appropriate. Sensitive care from midwives that provides good levels of support, tuned in to the woman and family’s self-perceived needs, may make a difference. In addition minority groups (particularly refugees and asylum seekers) will benefit particularly from continuity of care and carer (McCourt & Pearce 2000).

Housing

Housing is important for both the physical and psychological health of parents and children. Local authorities in the UK have a statutory duty to provide housing for families who are homeless, including pregnant women, but this may involve temporary accommodation that is not well suited to caring for a child. The duty to provide accommodation for those in unsuitable housing is less clear cut and many families join long waiting lists, with priority given to those with the highest ‘points’ for several categories of need. Local authorities may also nominate families to the waiting lists of housing associations, trusts and cooperatives, some of which also operate their own application systems. Midwives may be asked to support applications for housing or improved housing, usually by writing letters.

Accommodation with support may be available or offered for mothers and babies in certain circumstances, including refuges for women experiencing domestic abuse and supported accommodation for mothers of school age, or those experiencing depression or other mental health problems. Shortage of specialist mother and baby facilities, however, may limit what can be offered to women who need such support. The emphasis is, where possible, on providing care for mothers and babies together or, when children need accommodation without their mothers, on gaining support from the wider family if possible or providing foster care.

Voluntary and independent services

Voluntary organizations have been a major influence by showing what can be done and by campaigning for particular interest groups or services. They are linked to a long tradition of charitable work undertaken before the advent of the modern welfare state and were traditionally often linked with religious groups, as were the early hospital services in many countries. Voluntary organizations have shifted over time from being primarily charitable to a mutual or self-help focus, with many organizations founded by relatives of people in need of long-term services and, more recently, service user organizations. Government policy since the 1980s in the UK has strongly encouraged broadening the range of organizations providing services, including private companies. Voluntary and private providers of care are often referred to in policy terms as ‘the independent sector’.

Voluntary organizations have generally combined two rather different roles effectively: that of campaigning or providing information and advice and that of providing community health or social services. Services provided were often innovative, or responded to a gap in provision, which would, if effective, gradually be adopted by the statutory service providers. Following the NHS and Community Care Act 1990, they were encouraged to take on a far greater role in service provision and in some areas are now key providers of essential services such as residential and day childcare (Box 51.7).

Box 51.7 Voluntary organizations relevant for pregnant women and families with young children

A number of directories of local and national organizations are published and will be valuable to keep to hand for reference. (See also links on the website: www.tiger.gov.uk)

Services for mothers with disabilities

A range of services are provided by local authorities and voluntary or mutual support groups for women with disabilities, including those who are mothers. Although many are informal, and benefit from being so, it is important to remember the framework of rights and procedures provided by the NHS and Community Care Act 1990 and subsequent Disability legislation. In addition to service information, it is important for midwives to enhance their own awareness of disability issues, in order to provide a good service to all women whatever their needs. Issues for mothers with physical disabilities are considered in Chapter 3.

Learning disability

Midwives need awareness of learning disability issues both to support parents who may have some form of learning disability but also, increasingly, to provide information and support to all pregnant women offered screening for different disabilities. The issues surrounding parents with learning disabilities are particularly sensitive since social policy in the UK and other industrialized societies has historically been strongly influenced by eugenic ideas and focused on preventing people with disabilities from reproduction or parenthood. Many individuals are still sterilized, if not through force then by persuasion, or are encouraged to terminate pregnancies. In this context, disabled activists and academics have argued that the availability of screening and termination for impairments reflects and contributes to assumptions that physical or intellectual impairment is always and only a negative thing. Such a cultural environment is likely to impact on the feelings of people with such impairments, particularly when approaching the issue of parenthood. A number of theorists have, therefore, identified three different models of disability: the medical (or individual deficit model), the religious (or moral) model and the social oppression model. The last of these models recognizes that disability occurs as a result of social forces rather than simply because of the person’s impairment. What may be disabling for particular individuals with impairments are features of that environment, for example emphasis on literacy, design of buildings, or stigmatizing attitudes (Barnes et al 1999, Oliver 1996).

The category ‘learning disability’ covers a wide span and includes people who will need very high levels of support in becoming parents. Professional knowledge of learning disability, like ‘lay’ knowledge, is often very limited, partly because of the history, before recent philosophical and policy changes, of keeping people with disabilities socially segregated. ‘Mental handicap’ hospitals were built in the UK in the early part of the twentieth century (rather like the psychiatric asylums built before them) as geographically isolated institutions that functioned rather like self-sufficient communities (Alasewski 1986). Midwives need to learn more about learning and other disabilities to provide education and support for mothers with disabilities and to advise and counsel parents about antenatal screening and diagnostic tests (Dixon 1997).

Mental health and illness

The prevalence of mental health problems among women is acknowledged to be high, and mental health problems are far more widespread within the population than many people imagine, since mental illness is often associated with distorted media-based images of psychosis or violence. The importance of midwives’ attention to mental health issues is discussed in Chapter 36B. The public health emphasis in the National Service Framework (DH 2004a) is particularly focused on social deprivation as a major predisposer to mental health problems, on maternal mental health problems and their potential impact on the whole family. As with other community health and social care issues, therefore, midwives have great potential, as well as responsibility, to support women and families during this critical time of transition and development for women and families.

Conclusion

This chapter has highlighted key areas of community health and social services with which midwives need to be familiar. Some are important for general awareness and some for more specific roles such as providing advice, support or referral. A textbook can only provide an introduction and these areas have seen radical and rapid change in recent years. The references and further reading suggestions below will provide some pointers for developing further knowledge.

Acheson D. Independent enquiry into inequalities in health. London: The Stationery Office, 1998.

Alasewski A. Institutional care and the mentally handicapped. London: Croom Helm, 1986.

Barker D J P. Mothers, babies and health in later life. Edinburg: Churchill Livingston, 1998.

Barnes C, Mercer G, Shakespeare T. Exploring disability, a sociological introduction. Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999.

Beake S, McCourt C, Rowan C. Evaluation of the role of an infant feeding support worker in the community to support breastfeeding in disadvantaged women. Maternal & Child Nutrition. 2005;1(1):32-43.

Bulmer M. The social basis of community care. London: Allen & Unwin, 1987.

Carnell J, Kline R. Community practitioners and health visitors’ handbook. Abingdon: Radcliffe Medical, 1999.

Cleaver H, Unell I, Aldgate J. Children’s needs parenting capacity. The impact of parental mental illness, problem alcohol and drug use, and domestic violence on children’s development. The Stationery Office, London, 1999.

Clements L. Community care and the law. London: Legal Action Group, 1996.

Cloke C, Naish J, editors. Key issues in child protection for health visitors and nurses. London: Longman, 1992.

Cowley S. Public health in policy and practice. A sourcebook for health visitors and community nurses. Edinburgh: Baillière Tindall, 2002.

Crafter H. Health promotion in midwifery. London: Principles and practice. Arnold, 1997.

DES (Department for Education and Skills). Every child matters: change for children. London: The Stationery Office, 2004.

DoH (Department of Health). The health of the nation. London: HMSO, 1992.

DoH (Department of Health). Changing childbirth: report of the expert maternity group. London: HMSO, 1993.

DoH (Department of Health). The new NHS: modern, dependable. Cm 3807. London: The Stationery Office, 1997.

DoH (Department of Health). NHS (Primary Care) Act. London: DoH, 1997.

DoH (Department of Health). Our healthier nation. A contract for health. Cmd 3852. London: The Stationery Office, 1998.

DH (Department of Health). The Health and Social Care Act. London: TSO, 2001.

DH (Department of Health). National Services Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services. London: The Stationery Office, 2004.

DH (Department of Health). MMR information pack. 2004. Online. Available www.dh.gov.uk.

DH (Department of Health). Health Reform in England: update and commissioning framework. London: The Stationery Office, 2006.

DH (Department of Health). Our health, our care, our say: a new direction for community services. London: The Stationery Office, 2006.

DH (Department of Health). Maternity matters: choice, access and continuity of care in a safe service. London: The Stationery Office, 2007.

DH (Department of Health). Commissioning framework for health and well-being. London: The Stationery Office, 2007.

Dimond B. Legal aspects of care in the community. London: Macmillan, 1997.

Dixon K. Practical tips for supporting pregnant women with learning disabilities. MIDIRS Midwifery Digest. 1997;7(1):40-42.

Donnison J. Midwives and medical men. Barnet: A history of the struggle for the control of childbirth. Historical Publications, 1988.

Harper-Bulman K, McCourt C. Somali refugee women’s experiences of maternity care in west London: a case study. Public Health. 2002;12:365-380.

HM Government. Working together to safeguard children: A guide to inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children. London: The Stationery Office, 2006.

House of Commons Social Services Committee. Perinatal and neonatal mortality (the Short report). London: HMSO, 1980.

Hunt S, Symonds S. The social meaning of midwifery. London: Macmillan, 1995.

IDS (Incomes Data Services). Maternity and parental rights, employment law handbook, IDS, London, 2007. Updated annually. Online. Available www.incomesdata.co.uk/studies/maternity.htm.

Jones L, Sidell M. The challenge of promoting health. Basingstoke: Exploration and action. Macmillan/Open University, 1997.

Leap N, Hunter B. The midwife’s tale: an oral history from handy women to professional midwife. London: Scarlett Press, 1993.

Lewis G, editor. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH). Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer 2003–2005. The seventh report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. London: CEMACH, 2007.

McCourt C. Becoming a parent. In Page L, McCandlish R, editors: The new midwifery. Science and sensitivity in practice, 2nd edn, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2006.

McCourt C, Page L. Report on the evaluation of one-to-one midwifery, Centre for Midwifery Practice, Thames Valley University, London, 1996. Online. Available www.health.tvu.ac.uk/mid.

McCourt C, Pearce A. Does continuity of carer matter to women from minority ethnic groups? Midwifery. 2000;16:145-154.